|

Discover what implied dialogue is and four ways you can use it in your novel, whatever the genre, to enrich your readers’ experience.

|

|

TABLE 1

Text |

Type of prose |

Psychic distance between narrator and reader

|

|

‘Spoiler,’ said Reynolds. ‘I re-interviewed the surviving witnesses and they agreed that Anthony Lane opened fire at the Mary Engine and the jars on the rack. Before you ask, they were both interns and didn’t know where the items had come from.’

|

Direct speech

|

Wider

|

|

The dead guy, a certain Branwell Petersen, MIT graduate and former Microsoft employee, had died, the witnesses thought, because he stepped between the shooter and the Rose Jars.

|

Implied dialogue

|

Closer

|

|

‘The interns said he threw himself into the line of fire,’ said Reynolds. ‘As if his life was less important.’

|

Direct speech

|

Wider

|

2. Summarising to avoid repetition

A narrative summary enables authors to imply the spoken sharing of information without actually putting the whole conversation down on paper twice.

EXAMPLE

In the excerpt in Table 2a below, the protagonist – with the help of a companion – has escaped from an unknown location after being kidnapped.

|

TABLE 2a

Text |

Type of prose |

|

I stopped to orientate myself and spotted a street sign – Coldharbour Lane. I’d been in bloody Brixton the whole time. […] I wanted off the street, but didn’t want to put a random homeowner in danger. Instead we ran left towards the train station.

|

Narrative: Location of lair

|

|

[…] After less than a hundred metres, Foxglove was showing signs of serious distress and I felt her stumble a couple of times, but we’d reached the shopping parade by then and fortunately the Nisa Local was still open. A nervous black girl of about fifteen who was manning the tills gave us a weary look of disgust as we rushed in. Then got all confused when I told her I was a police office and that I needed to use a phone.

[…] I retreated with Foxglove into the corner where we’d be hidden by the shelves and called Guleed. |

Narrative: Location of store

|

|

[…] Guleed picked up, and I said, ‘We’re in the Nisa Local near Brixton Station and Chorley’s lair is on Coldharbour Lane.’

|

Direct speech: Repetition of narrative x2

|

But actually, I’ve butchered it. The real excerpt from pp. 329–30 of Lies Sleeping, also by Ben Aaronovitch, looks like this:

|

TABLE 2b

Text |

Type of prose |

|

I stopped to orientate myself and spotted a street sign – Coldharbour Lane. I’d been in bloody Brixton the whole time. […] I wanted off the street, but didn’t want to put a random homeowner in danger. Instead we ran left towards the train station.

|

Narrative: Location of lair

|

|

[…] After less than a hundred metres, Foxglove was showing signs of serious distress and I felt her stumble a couple of times, but we’d reached the shopping parade by then and fortunately the Nisa Local was still open. A nervous black girl of about fifteen who was manning the tills gave us a weary look of disgust as we rushed in. Then got all confused when I told her I was a police office and that I needed to use a phone.

[…] I retreated with Foxglove into the corner where we’d be hidden by the shelves and called Guleed. |

Narrative: Location of store

|

|

Guleed picked up, and I told her where I was, and where Chorley’s lair was, and let her get on with it.

|

Implied dialogue

|

The repetition is gone. Instead, of laboured direct speech that tells readers what they already know, the implied dialogue is taut and pacy, and lets us move on to the next part of the scene.

Summarising information via implied dialogue doesn’t necessarily reduce the word count, but that’s fine. The goal is not to necessarily to reduce the number of words (though that may be the result) but to keep the reader interested and drive the story forward.

3. Breaking up would-be monologues

However, when there’s a lot of detail, that information can turn into what feels like a monologue. The reader can end up dislocated from the environment, as if the speaker is talking in a vacuum or floating in white space. You might see this referred to as ‘talking heads syndrome’.

Implied dialogue is the antidote. It breaks up the dialogue so that while some of what was said is rendered in direct speech, chunks of it are voiced by the narrator. That is, what was actually spoken by the non-viewpoint character is implied.

EXAMPLE

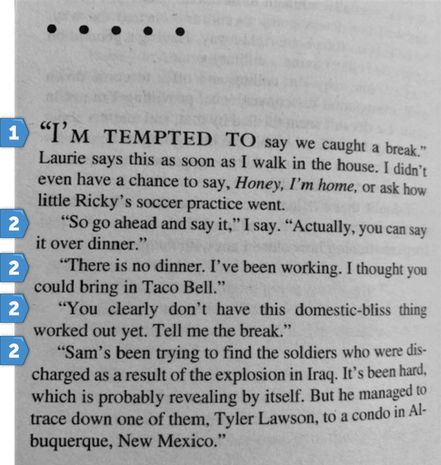

In Table 3 below is a fine example from False Value again, this time on p. 287. Consider how long Reynolds’s spiel would have been if Aaronovitch hadn’t broken it up by allowing the protagonist and first-person narrator, Peter Grant, to bear some of the burden.

It’s implied that the 113 words about what happened on August 2015 were spoken by Reynolds, but it’s Grant who delivers the information to the reader on her behalf. The monologue has been avoided but we know exactly how that conversation went.

|

TABLE 3

Text |

Type of prose |

Psychic distance between narrator and reader

|

|

I flipped the master power switch as soon as I was inside and pulled a Coke out of the fridge to serve as a coffee substitute while I waited for my PC to boot up. As soon as Skype was running, Reynolds’s call flashed up.

|

Narrative

|

Closer

|

|

‘What was all that about?’ I asked when I saw her face.

|

Direct speech

|

Wider

|

|

‘Skinner’s been connected to another case,’ she said.

|

Direct speech

|

Wider

|

|

At 10.15 on a Monday morning in August 2015, one Anthony Lane walked into the offices of an obscure tech start-up in San Jose carrying a concealed handgun. He talked his way past the receptionist before using the threat of force to gain access to the secure area at the rear and then, once he was in, opened fire. One person was killed instantly, two others were wounded and Lane himself was shot eight times in the back by a responding police officer. The attack barely made the news, being just one of several hundred to several thousand – depending on where you set the parameters – of active shooter incidents so far that year.

|

Implied dialogue

|

Closer

|

|

‘It wasn’t on my list,’ said Reynolds, ‘because the perp was dead.’

|

Direct speech

|

Wider

|

4. Making direct speech more impactful

EXAMPLE

The excerpt in Table 4 is from p. 369 of Lies Sleeping. The author uses a combination of direct speech, implied dialogue and narrative to present a coherent telling of the what the characters are saying and doing.

In this case, the implied dialogue is how readers know about the relatively mundane conversations that have taken place between the characters, but note in particular the penultimate line in which we learn that Guleed said she’d been about to phone.

What that does is put her closing direct speech centre stage. And that’s right and proper because it’s anything but mundane. It’s a section-closer that drips with suspense and tension – compelling the reader to turn the page so they can find out more about the problem Guleed’s identified, what the implications are and how the team are going to fix it.

|

TABLE 4

Text |

Type of prose |

|

‘I’ve checked for booby traps and handed it over to the local boys. Alexander is sending a search party tomorrow.’

|

Direct speech

|

|

He asked after Stephanopoulos and I passed on the assurances that Dr Walid had given me. I asked if he was heading back tonight and he said he was.

|

Implied dialogue

|

|

‘Anything else to report?’ he asked.

|

Direct speech

|

|

‘A creeping sense of existential dread,’ I said. ‘Apart from that I’m good.’

|

Direct speech

|

|

‘Chin up, Peter. He’s on his last legs – I can feel it.’

|

Direct speech

|

|

Once Nightingale had rung off I called Guleed, who’d been arriving as a nasty surprise to bell foundries and metal casting companies from Dudley to Wolverhampton all day.

|

Narrative

|

|

She said she’d been just about to phone.

|

Implied dialogue

|

|

‘I was right,’ she said. ‘There’s another bell.’

[SECTION BREAK] |

Direct speech: Standout one-liner

|

Summing up

And while direct speech that’s rich in voice, conveys mood, and shows intent is knockout, it may be that you’re concerned about excluding your readers – or, worse, boring them. If that's the case, experiment with this tool and see what effect it has on your prose when you mix things up a little.

Related resources and cited texts

- Dialogue resource centre

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level (book)

- False Value, Ben Aaronovitch, Gollancz, 2020

- How to Line Edit for Suspense (multimedia online course)

- Lies Sleeping, Ben Aaronovitch, Gollancz, 2018

- Narrative Distance: A Toolbox for Writers and Editors (multimedia online course)

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: X at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

What’s in this post?

- The difference between dialogue and narrative

- Using speech snippets as a narrative device

- Different styles of punctuation

- Using free indirect speech as an alternative

- Should the snippets be capitalized?

- Keeping the text lean and engaging

The difference between dialogue and narrative

Narrative is the telling of the story – how an external narrator or viewpoint character reports on the events taking place in the novel.

In the example below, the dialogue between the characters is in quotation marks. The surrounding text is narrative, and through it we learn what the viewpoint character – Milo – is thinking and what he can see and hear as the journey progresses.

The driver turned right at the junction, taking them over the bridge and south of the river.

Milo banged on the glass partition and shouted, ‘Hey, you’ve gone the wrong way, mate. We need to go north.’

‘Don’t worry yourself, sir,’ the driver said, his voice tinny through the intercom. ‘I’ve been told exactly where to take you.’

Note the following:

- I’ve used single quotation marks in line with British English-style convention.

- Each new speaker’s dialogue starts on a new line.

- The full stop after realm sits outside the closing quotation mark because this isn’t direct speech.

Here’s how it might look using US English style:

The driver turned right at the junction, taking them over the bridge and south of the river.

Milo banged on the glass partition and shouted, “Hey, you’ve gone the wrong way, mate. We need to go north.”

“Don’t worry yourself, sir,” the driver said, his voice tinny through the intercom. “I’ve been told exactly where to take you.”

Note the following:

- I’ve used double quotation marks.

- Each new speaker’s dialogue starts on a new line.

- The full stop after realm sits inside the closing quotation mark.

Using speech snippets as a narrative device

Although full sentences are used in the speech snippets, it’s not conventional dialogue. Rather, it’s narrating character’s recollection of utterances that give the reader a flavour of another character’s perspective.

Here’s an example punctuated using British English style. Note the following:

- I’ve used single quotation marks in line with British English-style conventions.

- Adamson’s speech snippets are not given a new line but incorporated into the narrative.

- Commas and a conjunction separate the speech snippets.

- Commas and a conjunction separate the speech snippets. These replace any full points that would have appeared if the actual conversation had been reported and rendered as dialogue.

- The commas sit outside the speech marks to indicate that this is Milo’s narrative rather than conventional dialogue.

And here’s an example punctuated using US English style, which some people might find a little trickier because of the question mark and the punctuation convention. In the three examples below:

- I’ve used double quotation marks in line with US English-style conventions.

- Adamson’s speech snippets are not given a new line but incorporated into the narrative.

- Commas and a conjunction separate the speech snippets. These replace any full points that would have appeared if the actual conversation had been reported and rendered as dialogue.

- Most of the commas still sit inside the speech marks as per US English style. The tricky bit is deciding what to do with the snippet containing a question mark.

Milo fumed. Stuck-up establishment idiots. They didn’t have a clue. Like that jerk Adamson barking on about his so-called obligations. During their previous meeting, Milo had nodded and smiled in all the right places while his boss informed him that “It’s all about the defence of the realm, old chap,” “Democracy’s lost its way, don’t you think?” “Got to look after our own, you know,” and “Government’s best done by our lot, not civilians.”

Option 2: Recast so that the snippet with a question mark is at the end of the sentence

Milo fumed. Stuck-up establishment idiots. They didn’t have a clue. Like that jerk Adamson barking on about his so-called obligations. During their previous meeting, Milo had nodded and smiled in all the right places while his boss informed him that “It’s all about the defence of the realm, old chap,” “Got to look after our own, you know,” “Government’s best done by our lot, not civilians,” and “Democracy’s lost its way, don’t you think?”

Option 3: Add a separating comma after the closing quotation mark to emphasize the separation

Milo fumed. Stuck-up establishment idiots. They didn’t have a clue. Like that jerk Adamson barking on about his so-called obligations. During their previous meeting, Milo had nodded and smiled in all the right places while his boss informed him that “It’s all about the defence of the realm, old chap,” “Democracy’s lost its way, don’t you think?”, “Got to look after our own, you know,” and “Government’s best done by our lot, not civilians.”

If you’re an editor who doesn’t have the scope to suggest a recast, I think Option 1 is fine. The question mark acts in place of a separating comma and avoids cluttering punctuation.

Option 3 indicates a clear separation but it’s a break from US-English style and clutters the paragraph with a comma that isn’t strictly needed.

Using free indirect speech as an alternative

Free indirect speech reads like direct first person dialogue but retains a third-person viewpoint. Here’s how it might work in our example.

Note how I’ve experimented with just a little italic for emphasis – old chap and our lot.

That’s so that although Milo is reporting the kinds of things he heard his boss say, the reader pays attention to the some of the tone of his boss’s voice and some of the language that Milo finds particularly grating.

Keeping the text lean and engaging

So what should you do if you’re passing an editorial eye over a sentence with lots of snippets?

Option 1: Can you create the same impact with fewer snippets?

Check whether all those snippets need to be there. Are some of them conveying similar information? If that’s the case, could you retain only those necessary to convey the essence of the character’s thought processes to the reader?

The example below has eight snippets.

Yes, Adamson might have uttered all of those statements, but capturing the essence of his mindset can be still achieved my omitting at least three of them.

I recommend you pick the utterances that are most powerful. That way, you'll ensure your reader remains engaged.

Option 2: Create two sentences from one

If editing out some dialogue snippets isn’t an option, try breaking the sentence into two.

Option 3: Mix up dialogue snippets and free indirect speech

Another option is to combine two different literary tools – direct speech snippets and free indirect speech. Here’s how it might work.

Again, I experimented with just a little italic to draw attention to Adamson's tone and its grating effect on Milo, and added an action beat in parentheses to highlight Adamson's readiness to break the law.

This option ensures the use of direct speech isn’t overworked, and instead gives the reader a different way to access the information in the narrative about how Adamson’s mind works.

Should the snippets be capitalized?

If I was dealing with partial dialogue, I'd approach the text as in the next example.

Summing up

However, writers and their editors need to ensure that readers won’t be tempted to skim. For that reason, pay attention to:

- consistent punctuation that supports readability, clarity and style

- brevity that captures the essence of the character’s perspective

- whether different tools could be combined to make the prose more interesting.

Related resources

- Book: Editing Fiction at Sentence Level

- Book bundle: Transform Your Fiction series

- Courses: The Fiction Line Editing Bundle

- Course: How to Line Edit for Suspense

- Course: How to Write the Perfect Fiction Editorial Report

- Course: Narrative Distance: A Toolbox for Writers and Editors

- Free resources: Dialogue

- Free resources: Line craft

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

What’s in this post?

- What is dialogue?

- What is an action beat?

- Midstream dialogue interruptions: Using dashes

- Which case to use: Upper or lower?

- How to avoid using three consecutive punctuation marks

What is dialogue?

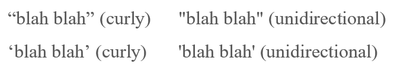

Depending on your style of choice, these marks can be either singles (‘blah blah’) or doubles (“blah blah”).

It’s more common to see double quotation marks used for books written in US-English style, and single marks used for books written in British-English style, but this is a convention rather than a rule. Consistency is what authors and editors aim for, so make your choice and stick with it.

What is an action beat?

That’s particularly useful when the narrative style is limited to the perspective of a single viewpoint character, a common and effective style of writing for many commercial fiction authors.

Examples of dialogue with action beats

In these examples, I’ve placed the action beats in the middle of the dialogue so you can focus on how the various beats I’ve chosen convey different emotions to the reader: frustration in the first, contemplation in the second, and boredom in the third.

‘So Mac’s not delivering the report for another week?’ Louise drummed her fingers on the table. ‘Okay. Let’s make a backup plan.’

‘So Mac’s not delivering the report for another week?’ Louise glanced at the clock and yawned. ‘Okay. Let’s make a backup plan.’

Note that none of these action beats are interrupting the speaker midstream. When they do, the punctuation can become a little more challenging.

Midstream dialogue interruptions: Using dashes

- Spaced en dashes (–) are a popular convention in British-English style.

- Closed-up em dashes (—) are a popular convention in US-English style.

This is not the law, not a rule, not the only way or the right way. It’s just the style that many publishers and independent authors choose to follow and that readers are used to seeing. Again, consistency is recommended so that readers aren’t unnecessarily distracted.

Example 1

Here’s an example written in British-English style, using spaced en dashes and single quotation marks.

And here it is again in US-English style, using closed-up em dashes and double quotation marks.

Example 2

Here’s an example written in British-English style, using spaced en dashes and single quotation marks. This time we’re dealing with an additional punctuation mark: the ellipsis.

And here it is again in US-English style, using closed-up em dashes and double quotation marks.

Which case to use: Upper or lower?

The action beats contained within the parenthetical dashes don’t start with a capital letter. Instead, the convention asks for lower case because the text is interrupting the dialogue midstream.

Avoiding three consecutive punctuation marks

- The ellipsis shows that the speaker takes a pause.

- The closing quotation marks indicates that the speech has stopped.

- The dash marks interruptive narrative and tells the reader that the speech will resume after the action beat.

However, some authors feel uncomfortable with multiple punctuation marks. If that’s you, you could try the following:

1. Remove the ellipsis and let the reader insert their own pause

Without the ellipsis, it’s not as clear to the reader if the scrolling is happening at the same time as the character is speaking or if she takes a pause, but does it really matter? In this case, probably not.

2. Tell (rather than show) the pause

If an author feels it’s absolutely necessary for the reader to know about the pause but doesn’t want to show it with an ellipsis, they could tell it (she paused).

Some might consider this a less elegant solution – a little wordy perhaps – but most readers likely won’t bat an eyelid unless those told pauses and hesitations are littering a text.

Summing up

If you want to interrupt dialogue midstream with action beats, try setting off the beat with dashes.

The choice of whether to use single or double quotation marks and spaced en dashes or closed-up em dashes is the author’s (or the publisher’s). If you’re a freelance fiction editor, check what your client’s style preferences are.

Once the style choice has been made, go for consistency so that readers can concentrate on immersing themselves in the story rather than untangling the punctuation.

Related line-craft resources

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

In this post ...

- What a dialogue tag is

- Back-loaded tags

- Mid-loaded tags

- Front-loaded tags

- Impact level, psychic distancing and lyricism in front-loaded tags

What a dialogue tag is

- Are you enjoying reading that blog post?’ Louise said.

- ‘Are you enjoying reading that blog post?’ she asked.

In the above examples, the tags are shown in bold and comprise the subject (someone’s name or their pronoun) doing the speaking, and the verb from which the reader can infer that the action of speech is taking place.

Commonly used effective verbs include ‘said’, ‘asked’, ‘replied’, ‘whispered’, ‘muttered’, ‘yelled’, ‘continued’ and ‘added’.

Ineffective dialogue tags use verbs that bring to mind action that’s not related precisely to speech but to some other behaviour. Examples include ‘sneered’, ‘grimaced’, ‘laughed’, ‘harrumphed’, ‘huffed’, ‘sighed’, ‘snarled’ and ‘urged’.

Positioning tags in fiction:

Back-loading, mid-loading and front-loading

So where might they go?

Dialogue tags can be front-loaded, mid-loaded and back-loaded.

Back-loaded dialogue tags

Back-loaded tags come after the speech and are used commonly. Consider using them in the following circumstances:

- Length of dialogue: Your character’s dialogue is a short burst and you want to ensure the reader’s attention is focused on what’s being said straightaway, rather than who’s saying it.

- Impact level: The dialogue is relevant but low key. There’s no punchline that might be flattened by a tag.

EXAMPLES

Mid-loaded dialogue tags

Mid-loaded tags come between the speech. They, too, are a popular choice for writers. Consider this option in the following circumstances:

- Length: The dialogue stream is longer and you want to ensure your readers don’t wait too long to discover who’s speaking.

- Rhythm and context: You want to introduce a natural pause so that the speech doesn’t turn into a monologue. You can also supplement the tag with descriptive action that grounds the dialogue in the environment and helps the reader picture the scene.

- Impact level: You’ve written a witty, suspenseful or impactful punchline into the dialogue and don’t want it interrupted or flattened by a tag.

- Interrupted speech: You’ve written speech that’s interrupted abruptly and don’t want the tag interfering with the interrupter’s speech.

EXAMPLE 1

This first example is from David Rosenfeld's Collared.

Notice how in the above example of single-character dialogue, which comprises a total of 51 words, the impact point is with the closing sentence: ‘Sign the damn form and send it in’. Because the tag’s located earlier, that dialogue gets to shine.

Compare the original with this version, which I’ve given a back-loaded tag:

Back-loading the tag strips ‘Sign the damn form and send it in’ of its oomph.

EXAMPLE 2

Here’s an example from Linwood Barclay’s Parting Shot that shows how mid-loaded tags can protect the flow of interrupted dialogue.

Notice how by mid-loading the dialogue tag, Ms. Plimpton’s interruption – indicated by the closed-up em dash at the end of Duckworth’s speech – feels more authentic because it’s given the space to flow.

Front-loaded dialogue tags

Front-loaded tags come before the dialogue. This position is the one least used in most commercial fiction, and there’s a good reason for that: reader focus.

Those familiar with advice on writing for the web will know that web copy needs to be front-loaded with relevant keywords. This means that the important stuff comes first. That’s because visitors to websites are busy and scanning for solutions to their problems. When they don’t get them fast, they become frustrated and are more likely to jump to another site.

If the novelist’s done their job well, readers will invest way more time in soaking up their prose than if they were shopping for a new duvet cover. Even so, every word in a piece of fiction needs to count, and readers should still be focusing on the most important stuff.

And so if you’ve written great dialogue, most of the time you’ll want to ensure your readers are focusing on it as soon as possible. Front-loading the speech, rather than the tag, helps achieve that.

That’s not to say that front-loaded dialogue tags don’t have their place. They do, and they can be extremely effective when used purposefully.

When front-loaded tags work:

Impact level, psychic distancing and lyricism

Impact level

A front-loaded dialogue tag can function in the same way as a mid-loaded one when it comes to speech containing impact points. Again, we’re talking about dialogue that’s witty, suspenseful, or closes with an impactful line that you don’t want to flatten with a tag.

EXAMPLE

Let’s return to the excerpt from Collared. Although Rosenfelt uses a mid-loaded tag, he could have opted for a front-loaded one and preserved the oomph in his closing sentence. Here’s how it might look:

Psychic distancing

If you want the prose to feel more expository so that the reader is less closely connected to the character, front-loading the tag might be just the ticket. Doing this widens the psychic (or narrative) distance.

A tag tells of speaking whereas dialogue shows what’s being said. By placing the tag first, you draw the reader away from the character’s voice and give the prose a more objective feel.

EXAMPLE

This excerpt is from Jens Lapidus’s Life Deluxe.

|

They veered onto a side street off Storgatan.

Jorge's phone rang. Paola: "It's me. Que haces, hermano?" Jorge thought: Should I tell her the truth? "I'm in Södertälje." "At a bakery?" Paola: J-boy loved her. Still, he couldn't take it. He said, "Yeah, yeah, ‘course I'm at a bakery. But we gotta talk later—I got my hands full of muffins here." They hung up. |

Lapidus has front-loaded dialogue tags and thoughts in this excerpt, and it’s an excellent example of psychic distancing in action. The centring of the characters rather than the speech gives the prose a detached, clinical feel that shows rather than tells mood.

Jorge is a drug-dealer operating in Stockholm’s shady underworld. He’s only just out of jail but already he’s frustrated with a life of honesty. In fact, he’s got only one thing on his mind: easy money.

The wider psychic distance means we get to see the world through Jorge’s eyes but without getting too close to him. Perhaps Lapidus doesn’t want us to empathize with him too much. Instead, he widens the psychic distance just enough that we can make up our own minds about whether Jorge deserves the trouble coming his way.

Lyricism

Repeated use of front-loaded tags with short bursts of dialogue can introduce a lyricism into prose whereby the tags function as more than just indications of who’s speaking. They become part of the poetry.

This approach can work particularly well with parody, satire and comedic prose.

EXAMPLE

Mari said, ‘No.’

Ahmed said, ‘Yes.’

Sol said, ‘Maybe.’

Dave said, ‘I couldn’t give a shit. Is that the best you’ve got?’

Arthur said nothing, just yawned.

The bell rang. Suitably insulted, I raised the SIG, shot each student in the head, and retired to the staff room.

Notice how the multiple front-loaded dialogue tags are performing anaphorically. Anaphora is the purposeful repetition of words or phrases at the beginning of successive clauses.

It’s often used in poetry and speeches. When it’s used in novels, that repetition draws the reader's eye and can show rather than tell mood – boredom, monotony or, as in this case, disinterest. The tags are therefore key to the lyricism, and as important as the speech.

Summing up

The key is to consider what purpose your tag is serving and how it can best amplify the speech, evoke mood, and improve rhythm.

Cited sources

- Barclay, l., Parting Shot, Orion; 2017 (p. 380)

- Boyd, W., Solo: A James Bond Novel, Vintage, 2014 (p. 260)

- Crosby, SA, Blacktop Wasteland, Headline, 2021 (Chapter 1, Kindle edition)

- Lapidus, J, Life Deluxe, Pan, 2015 (Chapter 1, Kindle edition)

- Rosenfelt, D, Collared, Minotaur Books, 2017 (Kindle edition)

Fiction editing training: Books and courses

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level (book)

- Fiction editing and writing resources (online library)

- How to Line Edit for Suspense (multimedia course)

- How to Write the Perfect Fiction Editorial Report (multimedia course)

- Narrative Distance: A Toolbox for Writers and Editors (multimedia course)

- Preparing Your Book for Submission (multimedia course)

- Switching to Fiction (multimedia course)

- What is anaphora and how can you use it in fiction writing? (blog post)

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

In this post ...

- What a dialogue tag is

- Why tags should support, not supplant dialogue

- Tagging: Positioning the verb in relation to pronouns

- Tagging: Positioning the verb in relation to nouns

- Standing out in ways that serve reader expectations

What a dialogue tag is

- ‘Are you enjoying reading that blog post,’ Louise said.

- ‘I’m interested in learning about dialogue,’ ze replied.

- ‘Can I stick to non-fiction editing?’ he asked.

Effective dialogue tags use verbs from which the reader can infer that the action of speech is taking place. Examples include ‘said’, ‘asked’, ‘replied’, ‘whispered’, ‘muttered’, ‘yelled’, ‘continued’ and ‘added’.

Ineffective dialogue tags use verbs that bring to mind action that’s not related precisely to speech but to some other behaviour. Examples include ‘sneered’, ‘grimaced’, ‘laughed’, ‘harrumphed’, ‘huffed’, ‘sighed’, ‘snarled’ and ‘urged’.

In this post, I’m going to focus on a question that beginner fiction authors and editors often ask about: where to locate ‘said’ and other effective tagging verbs.

First, though, here’s a quick recap about why ‘said’ is such a popular dialogue tag.

Why tags should support, not supplant dialogue

It’s become so conventional that when authors go out of their way to replace every instance of ‘said’ with alternatives, they risk creating prose that feels laboured.

Showy speech tags in particular stand out, and that means they pull the reader’s attention away from the dialogue and push it towards the speech tag.

That’s not a good reader experience because when characters communicate through speech, that’s where the action is in that moment. The tag should support that action, not supplant it.

You can find out more about how to tag dialogue in Editing Fiction at Sentence Level, including:

- Showy speech tags and underdeveloped dialogue

- Showy speech tags and double-telling

- Non-speech-based dialogue tags and the reality flop

- Alternatives to showy speech tags – more on action beats

- Using proper nouns and pronouns in dialogue tags

- Omitting dialogue tags

Now let’s look at where to place ‘said’ and other tagging verbs.

Tagging: Positioning the verb in relation to pronouns

- “I know,” she says. “I’m violating the cardinal rule of family night.” (Crouch: Dark Matter)

- ‘I could do your job myself, if that’s what you mean,’ he’d said at last. (Herron: Slough House)

- “I don’t have no fucking mask,” he said. (Connelly: The Dark Hours)

- “Me and Jaymie will call it. You want your boy to go too?” he said. (Crosby: Blacktop Wasteland)

Let’s have a look at those examples when the verb is placed before the pronouns.

- “I know,” says she. “I’m violating the cardinal rule of family night.”

- ‘I could do your job myself, if that’s what you mean,’ said he at last.

- “I don’t have no fucking mask,” said he.

- “Me and Jaymie will call it. You want your boy to go too?” said he.

There’s actually nothing grammatically wrong with any of the edited examples, though I wasn't able to retain the past perfect in the second. What has gone awry is the narrative setting.

The dialogue is written in contemporary English but the verb placement evokes a distinctly historical feel that’s inappropriate.

So how about when nouns rather than pronouns are in play?

Tagging: Positioning the verb in relation to nouns

- “There was nothing you could have done,” Judith said. (Coben: Fool Me Once)

- ‘Are you feeling the cold?’ Danny asked. (McDermid: 1979)

- “Sir, I can’t help you until you get a mask,” Moore said. (Connelly: The Dark Hours)

- “The question is, do you have the balls to back it up?” Kelvin said. (Crosby: Blacktop Wasteland)

Now let’s move the verb so that it sits before the noun.

- “There was nothing you could have done,” said Judith.

- ‘Are you feeling the cold?’ asked Danny.

- “Sir, I can’t help you until you get a mask,” said Moore.

- “The question is, do you have the balls to back it up?” said Kelvin.

Again, there’s nothing grammatically problematic about this structure. Furthermore, the switch doesn’t jar in the same way as when the subjects are pronouns.

So how should independent authors (and the editors who support them) approach the structure of a tag?

Standing out in ways that serve reader expectations

- lots of potential buyers of their books have come to expect this construction

- and it's the approach that mainstream presses tend to take.

When readers are presented with stories that break with convention, there’s a risk that the story’s no longer the standout feature. Instead, those with strong preferences focus on minutiae that challenge their expectations.

That focus isn’t serving a writer who’s trying to build their author platform.

Mick Herron has built enough trust with his readership with his brilliant Jackson Lamb series that no one will bat an eyelid when they read the following in Slough House:

‘Ian Fleming,’ said Diana Taverner. ‘Means “Death to spies”.’

Nevertheless, I scoured the first chapter of that book and found that in the main he still favours placing the verb after the subject.

Summing up

However, it’s such a common convention that I recommend indie authors of contemporary commercial fiction follow it.

When the subjects in a tag are pronouns, this structure is essential for retaining a contemporary feel. When the subjects are nouns, placing them first gives the pedants one less thing to gripe about.

Related reading and training

- Coben, H., Fool Me Once, Arrow, 2016 (Chapter 1, Kindle edition)

- Connelly, M, The Dark Hours, Orion, 2021 (Chapter 1, Kindle edition)

- Crosby, SA, Blacktop Wasteland, Headline, 2021 (Chapter 1, Kindle edition)

- Crouch, B, Dark Matter, Pan, 2017 (Chapter 1, Kindle edition)

- Harnby, L, Editing Fiction at Sentence Level, Panx Press, 2020

- Herron, M, Slough House, John Murray, 2021 (Chapter 1, Kindle edition)

- McDermid, V, 1979, Little, Brown, 2021 (Chapter 1, Kindle edition)

Fiction editing training courses

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

What’s covered in this post

- Why reduce the ‘I’

- Why ‘I’ still has a place front and centre

- Focusing on the exterior rather than the interior

- Reducing the use of filter words

- Removing speech and thought tags

- Applying the principles of free indirect speech

- Taking the 'I' out of introspection

- Balancing ‘I’ with ‘we’

Why reduce the ‘I’

Too much ‘I’ is a tap on the shoulder, one that says to the reader, ‘Just in case you’ve forgotten who the narrator is, here are lots of reminders.’

The consequence is that readers are pulled away. And that can actually increase rather than reduce narrative distance.

Why ‘I’ still has a place front and centre

However, they don’t rely on a first-person pronoun to convey experience, thought, speech and action. Below, I'll show you some examples – ones that ensure the intimacy of the narration style is left intact.

And so while we don’t want to obliterate ‘I’, because avoiding it completely would render the prose awkward, inauthentic and overworked, too much ‘I’ can be repetitive and interruptive. What’s required is a balance.

This post aims to offer you choice – fitting alternatives that retain intimacy and immediacy when you’re concerned you’ve overdone it.

1. Focus on the exterior rather than the interior

A little peppering in a more objective report will suffice because the reader knows that it’s coming from the narrator, and only the narrator. It has to be.

And while writers can make space to explore the viewpoint character’s emotional behaviour, the exterior world is what grounds their experience in the novel’s physical world. It gives the novel substance, and the reader something to bite into.

Instead of focusing on who’s doing the reporting, shift the prose towards what’s being reported.

What and who else is in the scene? Why are they there? How do they behave? What do they look like? This information can be reported without ‘I’ so that the reader experiences the physical world within which the narrator is operating.

Here’s an example from To Kill a Mockingbird (Harper Lee, Pan, 1974, p. 11).

|

Maycomb was an old town, but it was a tired old town when I first knew it. In rainy weather the streets turned to red slop; grass grew on the sidewalks, the court-house sagged in the square. Somehow, it was hotter then; a black dog suffered on a summer’s day; bony mules hitched to Hoover carts flicked flies in the sweltering shade of the live oaks on the square. Men’s stiff collars wilted by nine in the morning. Ladies bathed before noon, after their three o’clock naps, and by nightfall were like soft tea-cakes with frostings of sweat and sweet talcum.

People moved slowly then. They ambled across the square, shuffled in and out of the stores around it, took their time about everything. A day was twenty-four hours long but seemed longer. There was no hurry, for there was nowhere to go, nothing to buy and no money to buy it with, nothing to see outside the boundaries of Maycomb County. But it was a time of vague optimism for some of the people: Maycomb County had recently been told that it had nothing to fear but fear itself. |

Notice the (almost) absence of ‘I’. Scout – our narrator – tells us about the town she lived in: Maycomb. The recollection is hers certainly – ‘when I first knew it’ anchors it as such. It’s therefore intimate.

And yet because there’s only one I-nudge, we’re allowed enough emotional distance to step back and pan, like a roving camera, across Maycomb’s vista. We’re dislocated from Scout’s doing the experiencing and encouraged instead to focus on what she’s experiencing.

What’s happening here is a shift from the subjective to the objective.

Here’s an example of a short excerpt that’s subjective. The focus is on the I-narrator.

And here’s the real excerpt from David Rosenfelt’s Play Dead (Grand Central, 2009, p. 19). Now the focus is objective, yet in no way does this distance us from the centrality of the first-person narrator’s experience. We’re still deep in his head.

2. Reduce the use of filter words

Examples include noticed, seemed, spotted, saw, realized, felt, thought, wondered, believed, knew, and decided.

Filter words focus the reader’s gaze inwards (interior focus) on the manner through which the viewpoint character experiences the world – the how.

They come with a pronoun: I saw, they believed, we decided, she knew, he noticed.

By removing filter words, the reader’s gaze is shifted outwards (exterior focus) and onto what is being experienced. That can make for a more immersive read. Plus, the omission means we say goodbye to their accompanying pronoun: 'I'.

Here are a few examples to give you a flavour of how you might recast in a way that avoids first-person filtering.

|

‘I’ plus filter word. Reader’s gaze is inwards, on the how

|

Recast: Reader’s gaze drawn outwards towards the what

|

|

I recall the argument we had last week.

|

Last week’s argument is still fresh in my mind.

|

|

I recognized the man’s face.

|

The man’s face was familiar.

|

|

I saw the guy turn left and dart into the alley.

|

The guy turned left and darted into the alley.

|

|

I spotted the red Chevy from yesterday parked outside the bank.

|

There, parked outside the bank, was the same red Chevy from yesterday.

|

|

I still feel ashamed about the vile words I unleashed even after all these years.

|

The vile words I unleashed still have the power to bathe me in shame even after all these years.

|

3. Remove speech and thought tags

This will work best if there are no more than two characters. Most writers don’t extend the omission for more than a few back-and-forths before they introduce a reminder tag or an action beat.

Watching out for unnecessary tags is good practice regardless of narration style, but with a first-person narration it’s a particularly efficient way to declutter ‘I’-heavy prose.

Take a look at this excerpt from David Rosenfelt’s Play Dead, pp. 194–5. There are two characters in this scene: Andy Carpenter, the protagonist and narrator, and Sam Willis, the non-POV character on the other end of the phone.

“The woman's name is Donna Banks. She lives in apartment twenty-three-G in Sunset Towers in Fort Lee. I don't have the exact address, but you can get it.”

“Pretty swanky apartment,” he says.

“Right. I want you to find out the source of that swank.”

“What does that mean?”

“I want to know how she can afford it. She doesn't work, and she's the widow of a soldier. Maybe her name is Banks because her family owns a bunch of them, but I want to know for sure.”

“Got it.”

“No problem?” I ask. I'm always amazed at Sam's ability to access any information he needs.

“Not so far. Anything else?”

“Yes. I left her apartment at ten thirty-five this morning. I want to know if she called anyone shortly after I left, and if so, who.”

“Gotcha. Which do you want me to get on first? Although neither will take very long.”

“I guess her source of income.”

“Then say it, Andy.”

“Say what?”

“Come on, play the game. You're asking me to find out where she gets her cash. So say it.”

“Sam …”

“Say it.”

“Okay. Show me the money.”

“Thatta boy. I'll get right on it.”

The exchange involves 19 speech elements within the thread, but only 3 speech tags, and only one of those marks our first-person narrator.

At no point do we lose track, and at no point are we distracted by repetitive ‘I said’s.

4. Apply the principles of free indirect speech

In a nutshell, free indirect speech offers the essence of first-person dialogue or thought but through a third-person viewpoint. The character’s voice takes the lead, but without the clutter of speech marks, speech tags, italic, or other devices to indicate who’s thinking or saying what.

Here’s an example of third-person narration. Notice the filter words ‘glanced’ and ‘noticed’, the italic present-tense thought, and the thought tag:

Let’s change that to a first-person narration. The filter words are still there and there’s a thought tag with the ‘I’ pronoun.

Here’s what the third-person version could look like in free indirect style. The filter words and tags are gone. It feels like a first-person thought but the base tense and third-person narration remain intact.

And now the first-person version. All I’ve done is swapped out the pronoun ‘his’ for ‘my’.

5. Take the ‘I’ out of introspection

However, when prose is littered rather than peppered with constructions such as I wasn’t sure if, I didn’t know whether, I wondered if, it can feel muddled and be laborious to read. The reader might respond: Well, of course you’re wondering. Who else could it be? You’re the narrator.

Worse, readers might think the narrator’s rather self-absorbed and unsure of themselves. While that might be necessary now and then, it’s problematic if it’s a staple because a narrator who’s always focused on themselves, and who never instils confidence in us, can’t tell the story as effectively.

Look out for ‘I’-centred introspection and experiment with statements and questions that allow the ‘I’ to be assumed.

Here are a few examples to show you how it might work.

|

‘I’-centred introspection

|

‘I’-less introspection

|

|

I wasn’t sure if Shami was a reliable witness but I couldn’t afford to ignore her, given what she’d divulged.

|

Was Shami a reliable witness? Maybe, maybe not. She couldn’t be ignored given what she’d divulged.

|

|

I still didn’t know who the killer was.

|

The killer’s identity was still a mystery.

|

|

I wondered whether Shami was a reliable witness.

|

Shami might or might not be a reliable witness.

Shami’s reliability as a witness was hardly a given. Shami’s reliability as a witness was questionable. |

6. Balance ‘I’ with ‘we’

This is an opportunity to frame the narrative around ‘we’ rather than just ‘I’.

Here’s an excerpt from To Kill a Mockingbird (p. 162) in which Scout, Harper Lee’s first-person narrator, frames the recollection around not just her own experience but those of the people she was hanging out with.

A wagonload of unusually stern-faced citizens appeared. When they pointed to Miss Maudie Atkinson's yard, ablaze with summer flowers, Miss Maudie herself came out on the porch. There was an odd thing about Miss Maudie – on her porch she was too far away for us to see her features clearly, but we could always catch her mood by the way she stood. She was now standing arms akimbo, her shoulders drooping a little, her head cocked to one side, her glasses winking in the sunlight.

The effect is powerful because we’re shown rather than told a sense of her belonging, of her being in a group, of the togetherness of that experience. And that intensifies our immersion in her world.

Summing up

Try recasting sentences that start with ‘I’ more objectively, so that the focus is on the what – the emotion, the object, the person, the action and so on – rather than the sense being used to experience it or the I-narrator doing the experience.

Use the principles of free indirect speech to reduce your ‘I’ count. It’s a tool that encourages a narrowing of narrative distance to such a degree that the reader feels deeply connected to the viewpoint character – more like we’re reading a thought than straight narrative.

As for speech and thought tags, you might not need as many as you think. The speaker can usually be identified without them if there are only two people in the conversation. Removing redundant tags is worth considering whichever narration style you’re writing in.

Related resources

- 3 reasons to use free indirect speech

- 6 ways to improve your novel right now

- Author resource library (includes links to free webinars)

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level: A Guide for Beginner and Developing Writers

- Filter words in fiction: Purposeful inclusion and dramatic restriction

- Making Sense of Point of View: Transform Your Fiction 1

- What is head-hopping, and is it spoiling your fiction writing?

- Switching to Fiction: Course for new fiction editors

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Why speech in a novel is different

Every line of dialogue should have a purpose. If it doesn’t, it probably shouldn’t be in your book.

It can take courage to remove words you've spent an age crafting but as I hope to show in the example below, readers don't need every little detail. Less is so often more!

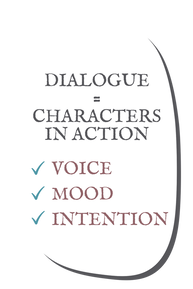

A three-pronged approach to dialogue

When we focus on those three things, we avoid dull dialogue – conversations about the weather, how someone takes their tea or coffee, and courtesy statements such as ‘Hi, how are you?’

Voice tells us who characters are, what makes them tick – their fears, frustrations, hopes and dreams, identity, preferences.

Perhaps their speech is abrupt, rude, measured, polite, sweary or seductive.

When we change the way a character speaks, we change their voice. And that means we change them.

Characters can show us how they’re feeling via their dialogue.

Emotionally evocative speech allows readers to access the internal experience of a non-viewpoint character. And that makes it a powerful tool.

Perhaps their speech is abrupt, assertive, hesitant, forceful, pleading. Using the right words means the speech tags and narrative won’t need to be cluttered with further explanation.

Intention is another way of framing subtext. How characters speak tells us what they want.

Perhaps they’re asking questions for the purpose of discovery and understanding whodunit (doctors, lawyers, PIs and police officers regularly use dialogue in novels to this end). Dialogue can express a multitude of motivations.

Ask yourself what your character wants every time they open their mouth.

Example: Real but mundane dialogue

“Hi, Kevin,” I say.

“Hey, Andy. How you doin’?”

“Not too bad, thanks. Christ, it’s cold out though. I need something to warm me up. Gonna grab a coffee. Want one? Laurie, you?”

Kevin nods.

Laurie says, “Please. Milk and sugar.”

“So Kevin,” I say as I hand around the drinks, “we need to talk about Petrone.”

It’s the first chance I’ve had to tell Kevin about my meeting with the guy. I fill him in. When I get to the part where Petrone denied trying to have me killed, Kevin asks, “And you believed him?”

“I did.”

“Just because that’s what he said?”

I nod. “As stupid as it might sound, yes. I’ve had dealings with him before, and he’s always told me the truth, or nothing at all. And he had nothing to gain by lying.”

“Andy, the guy has had a lot of people murdered. How many confessions has he made?”

Were you enthralled by the welcome and refreshments section, or did you just wish we could get to the point? I think I know the answer!

The slimmed-down version

These meetings are basically of dubious value, since all we seem to do is list the things we don’t understand in our preparation for a trial we don’t know will even take place.

It’s the first chance I’ve had to tell Kevin about my meeting with Petrone. I fill him in. When I get to the part where Petrone denied trying to have me killed, Kevin asks, “And you believed him?”

“I did.”

“Just because that’s what he said?”

I nod. “As stupid as it might sound, yes. I’ve had dealings with him before, and he’s always told me the truth, or nothing at all. And he had nothing to gain by lying.”

“Andy, the guy has had a lot of people murdered. How many confessions has he made?”

What readers don’t care about

And so he leaves all of that out and lets the reader imagine that this stuff took place. And it’s enough. In the published novel, as opposed to the version I butchered, the first line of speech is “And you believed him.”

With that, we’re straight into Kevin’s incredulity and concern, and his desire to understand what the team is dealing with in regard to Petrone.

Meanwhile, Andy has his lawyer hat on. His initial reply is succinct, so that we are left in no doubt about his belief that Petrone was telling the truth, and that he is determined to reassure Kevin.

This is no-messing dialogue that focuses on story, not whether the speech is what we might actually hear – in its entirety – in real life.

It’s an excellent example of an author ensuring that every word counts and that there’s no bus-stop-talk filler.

Summing up

- Is every line relevant to the story?

- Is the character speaking with purpose or taking up ink/pixels on the page?

- Can mundane chitchat be removed without damaging sense and flow?

- Could the dull stuff be replaced with speech that deepens character?

Want the booklet version of this post? It's available on my Dialogue resources library. Click on the cover below to hop over to the page. Once you're there, choose the Booklets icon.

More fiction editing resources for authors and editors

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level

- Making Sense of ‘Show, Don’t Tell’

- Making Sense of Point of View

- Making Sense of Punctuation

- How to Write the Perfect Fiction Editorial Report

- Switching to Fiction

- The Differences Between Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Copyediting and Proofreading (free webinar)

- How to Punctuate Dialogue in a Novel (free webinar)

- Resource library: Dialogue and thoughts

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

FIND OUT MORE

> Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

> Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

> Learn: Books and courses

> Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Review your novel for 6 common problems. None involve major rewriting, just relatively gentle recasts that will improve your prose significantly, and make your reader's experience more immersive.

1. Assess invasive adverbs

2. Remove redundant filter words

3. Take the spotlight off speech tags

4. Pick up dropped viewpoint

5. Trim anatomy-based action

6. Turn intention into action

1. Assess invasive adverbs

However, overuse is often a symptom of an author telling us what’s already been shown, which means the adverbs are repetitive and cluttering. In the two examples that follow, they can be ditched because 'fidgeted' shows the nervousness, and the apology in the dialogue shows the regret.

- Jane fidgeted nervously with the napkin.

- ‘I’m so sorry to keep you waiting,’ she said with regret. ‘It’s been one of those days.’

- Jane fidgeted with the napkin.

- ‘I’m so sorry to keep you waiting,’ she said. ‘It’s been one of those days.’

Even when adverbs are telling us something new, consider elegant recasts that use stronger verbs but still keep readers in the moment.

- Jane turned around suddenly and ducked.

- Jane opened the shed door cautiously and peeked in.

- Jane spun around and ducked.

- Jane inched open the shed door and peeked in.

2. Remove redundant filter words

The reader is already experiencing the story through a viewpoint character. For that reason, we often don’t need to be told that they realize, see, think or feel anything. We’re already in their heads.

It’s telling what’s already been shown.

- Jane’s phone trilled. She glanced at the screen and saw that it was James calling again.

- Matthew felt a thumping in his temples and thought about how that third glass of wine had been a bad idea.

- Jane’s phone trilled. She glanced at the screen. James again.

- Mathew’s temples thumped. That third glass of wine had been a bad idea.

Filtering pulls us out of the deep, limited viewpoint. Worse, it’s repetitive and obvious. Jane has already looked at the screen so we know her eyes are doing the work; telling us that she saw as a result of her glancing is redundant.

In the example where Matthew’s the narrative viewpoint character, we needn’t be told he feels the thumping in his temples, since if he weren’t feeling it he couldn’t report it. Nor do we need to know he’s thinking about that third glass because we’re already in his head.

3. Take the spotlight off speech tags

Sometimes tags aren’t even necessary because it’s obvious who’s speaking. Other times, we can replace a tag with an action beat than conveys movement and emotion.

Readers should be focused on the dialogue. If a showy tag is necessary to convey a character’s voice or mood, the speech might need a rethink.

In the examples below, the speech tags do the following:

- tell what the punctuation’s already shown

- tell what the dialogue’s already shown

- tell us what the dialogue could have shown but doesn’t

- express non-speech-related behaviour

- 'That’s extraordinary!’ Jane exclaimed, and ran her index finger over the polished wood.

- ‘Put the damn thing down now. That’s an order, soldier,’ Reja commanded, raising her rifle.

- ‘Stop,’ Mathew pleaded.

- ‘I really need to hit the sack,’ James yawned.

ALTERNATIVES

- ‘That’s extraordinary!’ Jane ran her index finger over the polished wood.

- ‘Put the damn thing down now.’ Reja raised her rifle. ‘That’s an order, soldier.’

- ‘Stop,’ Mathew said. ‘I’m bloody begging you.’

- James yawned. ‘I really need to hit the sack.’

4. Pick up dropped viewpoint

- The viewpoint character reports what they can’t know.

- The reader is given access to non-viewpoint characters' internal experiences.

The viewpoint character reports what they can’t know

Reporting what can’t be known often comes with filter phrases such as 'could tell (that)' and 'knew (that)'.

In this example, John is the viewpoint character. We experience the story though his senses.

There, behind the desk, sat Reja, the girl he’d dated two decades earlier.

‘Sergeant John Davis,’ he said, and held out his hand. He could tell she didn’t remember him.

Actually he can’t tell any such thing. It might seem that way, but for all John knows, she could be hiding it because she has another agenda. Telling us that’s not the case removes any underlying suspense – stops us asking the question.

This might seem like a small slip but it’s the kind of thing that turns over all the power of a limited/deep viewpoint to an all-knowing narrator and rips apart the tight psychic distance between reader and the viewpoint character.

Here are two recasts that avoid the viewpoint drop:

There, behind the desk, sat Reja, the girl he’d dated two decades earlier.

‘Sergeant John Davis,’ he said, and held out his hand.

She showed no sign of recognizing him.

There, behind the desk, sat Reja, the girl he’d dated two decades earlier.

‘Sergeant John Davis,’ he said, and held out his hand.

There was no recognition on her face.

Non-viewpoint characters’ internal experiences

Here we’re talking about head-hopping. It’s when readers are able to access emotions, mood and thoughts of a non-viewpoint character. In the example that follows, Reja is the viewpoint character.

Bloody fool. Who did he think he was? Reja jammed her hat down over her ears. No way was she leaving with him.

John could have kicked himself. He shouldn’t have come on that strong. Not after what she’d been through.

The solution is to recast the text so that these emotions, mood and thoughts can be inferred or accessed externally – for example, through movement or speech – by the viewpoint character only. Here’s a possible recast.

Bloody fool. Who did he think he was? Reja jammed her hat down over her ears. No way was she leaving with him.

John palmed his forehead and spluttered an apology. ‘I shouldn’t have asked. Not after … well, you know.’

5. Trim anatomy-based action

In the example below, we might remove the obvious body parts and focus more specifically on the part of John's legs doing the kicking and the impact of his action. As for the gun-toter, the hands have been ditched.

John kicked out with his legs. The woman stumbled, righted herself and came at him again, pistol raised in her hands.

ALTERNATIVE

John kicked out, slamming his heel into her kneecap. The woman stumbled, righted herself and came at him again, pistol raised.

6. Turn intention into action

Jane squeezed the detergent into the porridge. Just a couple of squirts to give Alice a taste of her own medicine.

However, when an author means to show the how of an action but tells of intention to act, there’s a problem. The red flag to watch out for is 'to'.

We can check whether the focus is on point by asking a question: What action do we want to show the reader (via Jane)?

If we want to show the reader that Jane can lift her wrist – because that’s what the first example below is showing us – we can leave as is.

However, that's rather dull; it's more likely that we want to show that Jane is checking the time, and so a leaner alternative is more effective.

Jane lifted her wrist to look at her watch. Bang on two.

ALTERNATIVE

Jane checked her wristwatch. Bang on two.

Summing up

And don't worry about them at first-draft stage. Use that space to get the words on the page. Put your sentence-level editing craft in play with a later draft, and once your story's structure, plot and characterization have been fully developed.

Further reading

- Author resource library (includes links to free webinars)

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level: A Guide for Beginner and Developing Writers

- Making Sense of Point of View: Transform Your Fiction 1

- Making Sense of Punctuation: Transform Your Fiction 2

- ‘Playing with sentence length in crime fiction. Is it time to trim the fat?’

- ‘Playing with the rhythm of fiction: commas and conjunctions’

- ‘What is anaphora and how can you use it in fiction writing?’

- '2 ways to write about physical pain'

- 'What is head-hopping, and is it spoiling your fiction writing?'

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

FIND OUT MORE

> Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

> Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

> Learn: Books and courses

> Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Dialogue tags, or speech tags, are complementary short phrases that tell the reader who’s talking. They’re not always necessary, particularly if there are only two speakers in a scene, but when they are used, this is what they look like:

- ‘Dump that corpse and don’t ever mention it again,’ the hooded guy whispered.

- “Thanks for holding the gun,” Tom said. “Now pull the trigger.”

- Marg turned. Smirked. Said, ‘Tomorrow. If you’re late, he’s late. Geddit?’

Said is often best because readers are so used to seeing it that it’s pretty much invisible and therefore less interruptive.

What’s the rule about where tags go?

Dialogue tags can be placed after, between or before dialogue. Authors sometimes ask which position is best or whether there’s a rule.

There is no rule. All three positions have advantages and disadvantages, depending on what you want to achieve.

Position: After dialogue

Readers are so used to seeing speech tags like said at the end of dialogue that they’re almost invisible. That allows the dialogue, rather than the speaking of the dialogue, to be the focus.

Below is a wee example from Recursion (p. 292). The speech takes centre stage; the doing of speech (screaming, in this case) comes afterwards.

Furthermore, when the tag comes after the dialogue, it can roll seamlessly into any supporting narrative, as shown in the example from The Ghost Fields (p. 194).

|

“Come on!” he screams.

‘It’s very … evocative,’ says Ruth. This is true. The brushwork may be crude, the planes out of perspective and the figures barely more than stick men, but there’s something about the work of the unknown airman that brings back the past more effectively than any documentary or reconstruction. |

There are a couple of potential disadvantages:

- In longer chunks of dialogue in scenes with more than two speakers, the reader will have to wait until the end of the speech to find out who’s saying what.

- Placement at the end of speech can flatten a one-liner or suspense point in dialogue.

Position: Between dialogue

Placing speech tags between dialogue is also common and unlikely to jar the reader. Here are three reasons why it works:

- The tag breaks up longer streams of dialogue, which is especially handy if a monologue’s rearing its head.

- We’re given an early indication who’s speaking. If there are more than two speakers in a scene, and the reader’s likely to be confused, placement between the speech is an effective solution.

- One-liners, suspense points and shocks get to take centre stage. Adding the speech tag at the end could flatten the tension.

Here are two examples in which the mid placement of the tag means the suspense isn't interfered with. The first is taken from The Ghost Fields (p. 194); the second is something I made up.

In the second example, rejig the sentence so that Tom said comes after all the speech, and notice how this makes the wallop vanish from the line about pulling the trigger.

Position: Before dialogue

Placement of the tag before the dialogue isn’t a no-no but it is a less common option and more noticeable.

A tag tells of speaking; dialogue shows character voice, mood and intention. When the speaker’s announced first, it’s a tap on the shoulder that draws attention to speaking being done. It expands what author and creative-writing expert Emma Darwin calls the ‘psychic distance’ between the reader and the speaker, which can flatten the mood.

And, yet, this can also be its advantage. That tap introduces a more staccato rhythm that can stop a reader in their tracks.

In this extract from Recursion (p. 292), the placement of the tag before the dialogue induces an acute sense of resignation – that dull thump in the pit of one’s stomach when the proverbial’s hit the fan.

Not placing tags: Omission

There’s no need to include a speech tag if it’s adding nothing but clutter. In the following example from Recursion (p. 125), the author has omitted them because there are only two speakers. He lets the dialogue, and its punctuation, inject the voice, mood and intention into the scene rather than telling us who’s speaking and how they’re saying it.

Summing up

Placement of dialogue tags isn’t about rules. It’s about purpose:

- Varying rhythm

- Respecting mood and suspense

- Clarifying who’s speaking

- Avoiding unnecessary clutter

For that reason, mixing up the position of speech tags can be effective.

Let’s end with an extract from Out of Sight (pp. 135–7), which demonstrates the varied ways in which author Elmore Leonard handles his tagging: beginning, between, end, and omission.

|

‘But you think they’re coming back,’ Karen said.

‘Yes, indeed, and we gonna have a surprise party. I want you to take a radio, go down to the lobby and hang out with the folks. You see Foley and this guy Bragg, what do you do?’ ‘Call and tell you.’ ‘And you let them come up. You understand? You don’t try to make the bust yourself.’ Burdon slipping back into his official mode. Karen said, ‘What if they see me?’ ‘You don’t let that happen,’ Burdon said. ‘I want them upstairs.’ |

Cited sources and further reading

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level, Louise Harnby, Panx Press, 2020

- How to Punctuate Dialogue (free webinar)

- Out of Sight, Elmore Leonard, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2017

- Recursion, Blake Crouch, Pan, 2020

- The Ghost Fields, Elly Griffiths, Quercus, 2015

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Each new paragraph signifies a change or shift of some sort ... perhaps a new idea, piece of action, thought or speaker, even a moderation or acceleration of pace. Still, the prose in all those paragraphs within a section is connected.

Paragraph indents have two purposes in fiction:

- Readability: They help the reader identify the shifts visually.

- Connectivity: They indicate a journey. Indented paragraphs are related to what's come before ... part of the same scene.

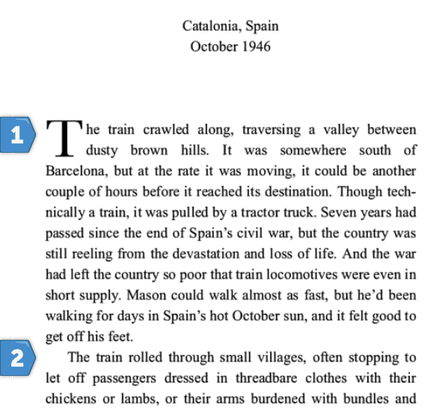

First lines in chapters and new sections

Chapters and sections are bigger shifts: perhaps the viewpoint character changes, or there's a shift in timeline or location.

To mark this bigger shift in a novel, it’s conventional not to indent the first line of text in a new chapter or a new section. You might hear editorial folks refer to this non-indented text as full out.

- This is standard with narrative and dialogue.

- The convention applies regardless of your line spacing.

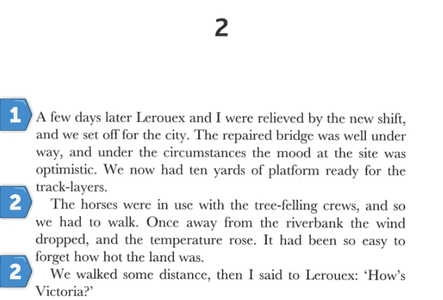

NARRATIVE LAYOUT

The following example is taken from Part 5, Chapter 2, of Christopher Priest’s Inverted World (p. 287, 2010):

- Paragraph 1 is the first in the chapter.

- The first line is not indented.

- The first lines of the paragraphs that follow it (2) are indented.

- Paragraph 1 is the first in the section.

- The first line is not indented.

- The first lines of the paragraphs that follow it (2) are indented.

- Paragraph 1 is the first in the chapter.

- The capital letter on the first and second lines is not indented.

- The first line of the paragraph that follows it (2) is indented.

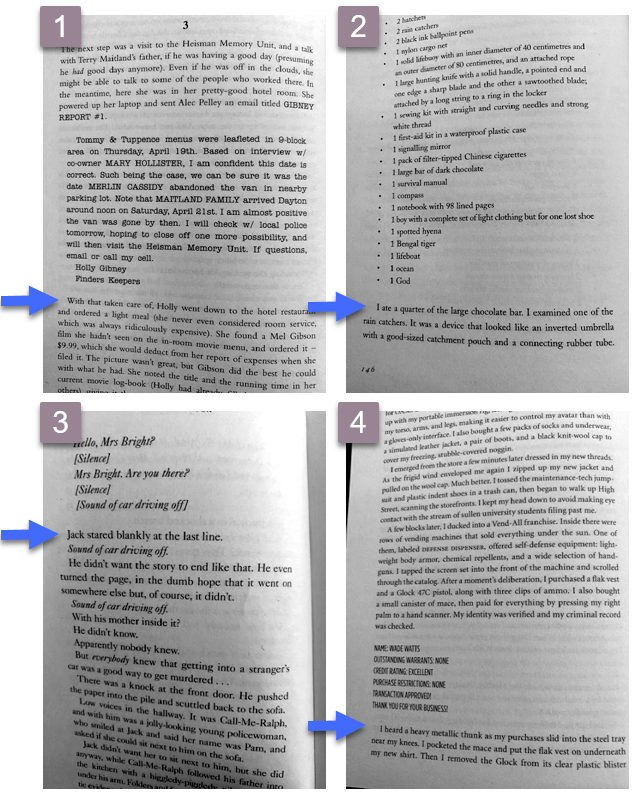

The same applies even if the chapter or section starts with dialogue, as in this excerpt from David Rosenfelt's Dog Tags (p. 192, Grand Central, 2010):

- Paragraph 1 is the first in the chapter.

- The first line is not indented.

- The first lines of the paragraphs that follow it (2) are indented.

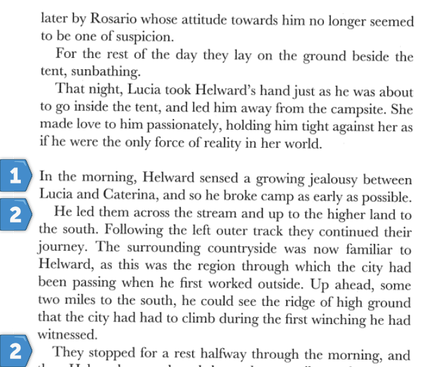

The example below from Blake Crouch's Recursion (p. 4, Macmillan, 2019) shows how the indentation works in the body text when there's a mixture of dialogue and narrative.

- Regardless of whether the prose is narrative or reported speech, the text is indented.

- The convention applies regardless of line spacing.

Even if you've elected to set your book file with double line spacing (perhaps at the request of a publisher, agent or editor), the indentation convention applies. Here's the Recursion example again, tweaked to show what it would look like:

Your novel might include special elements such as letters, texts, reports, lists or newspaper articles. Authors can choose to set off these elements with wider line spacing, but how do we handle the text that comes after?

Again, it's conventional to indent text that follows this content, regardless of whether it's narrative or dialogue. That's because of the connective function; the text is part of the same scene.

Here are some examples from commercial fiction pulled from my bookshelves.

- REPORT: The Outsider, Stephen King, Hodder, 2018, p. 252

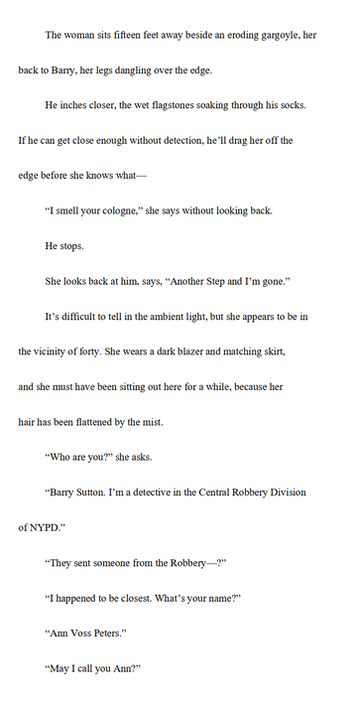

- LIST: Life of Pi, Yann Martel, Canongate, 2002, p. 146

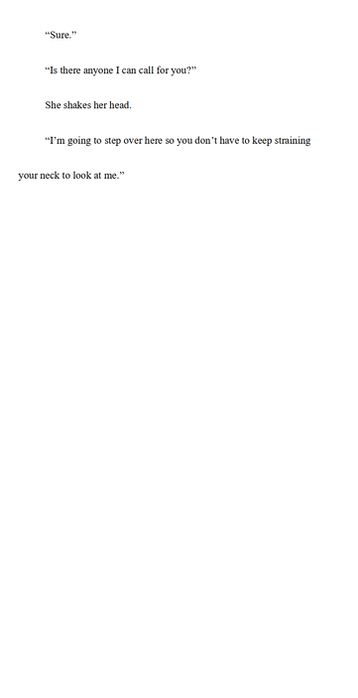

- TRANSCRIPT: Snap, Belinda Bauer, Black Swan, 2018, p. 36

- RECORD: Ready Player One, Ernest Cline, Arrow, 2012, p. 300

That's what I think's happened in the example below from Kate Hamer's The Girl in the Red Coat (p. 325, Faber & Faber, 2015). Of course, it took me only a split second to work out that the narrator is referring to the preceding letter, but it's a split second that took me away from the story because I'd assumed I was looking at a section break.

My preference would be to indent 'I touch my finger [...]' because that text is part of the scene, not a new section.

Let's finish with some quick guidance on creating first-line indents.

Avoid using spaces and tabs to create indents in Word. Instead, create proper indents. There are several ways to do this.

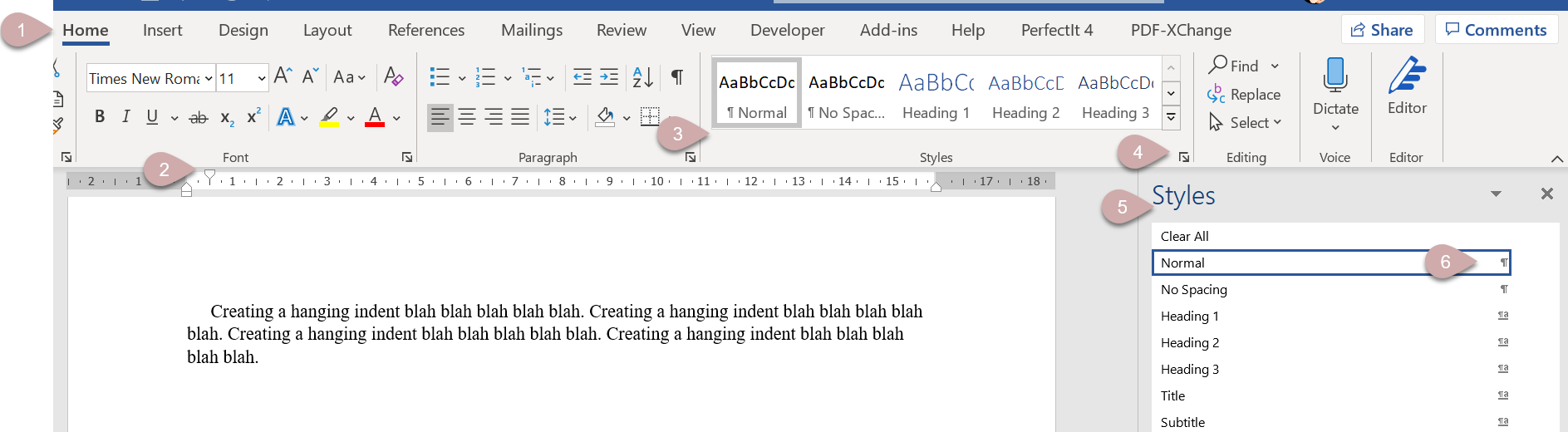

- Open the Home tab (1).

- Select your text.

- Move your cursor to the ruler and select the top marker (2).

- Drag it to the position of your preferred indent.

- Right-click on the style in the ribbon (3).

- Select 'Update Normal to Match Selection'.

- Open the Home tab (1).

- Open the Styles pane via the arrow icon (4).

- Select your text.

- Move your cursor to the ruler and select the top marker (2).

- Drag it to the position of your preferred indent.

- Go to the Styles pane (5) and right-click on the style (6).

- Select 'Update Normal to Match Selection'.

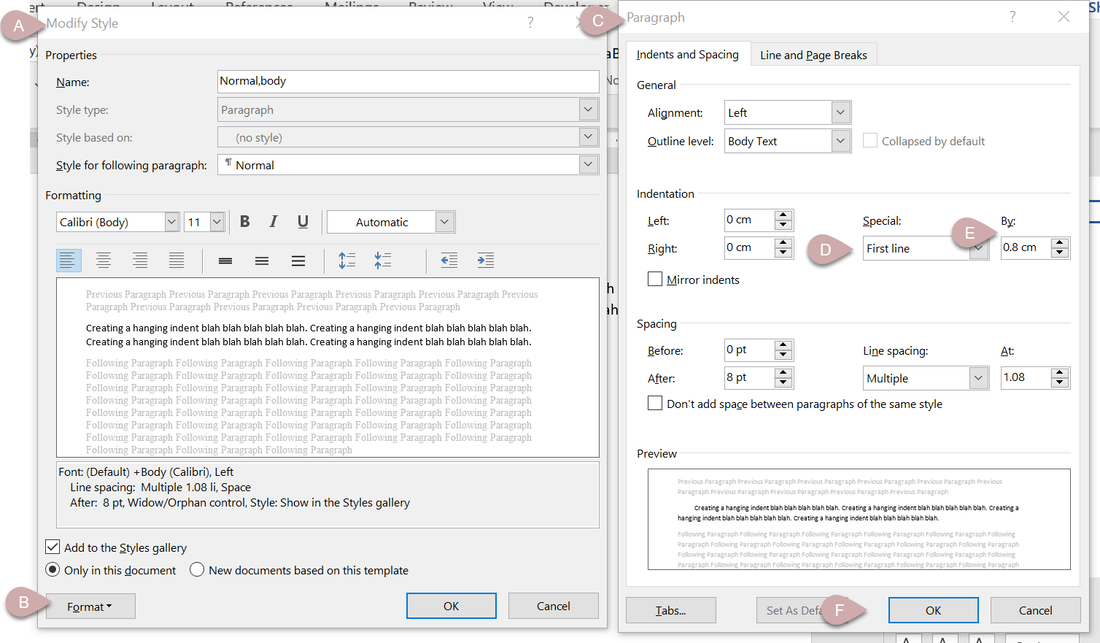

- Open the Home tab (1).

- Open the Styles pane via the arrow icon (4).

- Go to the Styles pane (5) and right-click on the style (6).

- Select 'Modify' to open the Modify Styles pane (A).

- Click on the Format button in the bottom left-hand corner (B).

- Select Paragraph to open the Paragraph pane (C).

- Make sure you're in the Indents and Spacing tab.

- Look at the Indentations section in the middle. Make sure 'First line' is selected under 'Special:' (D).

- Adjust the first-line indent according to your preference (E).

- Click OK (F).

- If using the ruler, ensure the markers (2) are aligned, one on top of the other.

- If using the styles pane, adjust the indent spacing (E) to zero.

If you need more assistance with creating styles, watch this free webinar. There's no sign-up; just click on the button and dig in.