|

Find out about 5 core character roles within a novel, and how the purpose they serve ensures the story stays focused.

|

|

Example from published fiction

Kate Hamer, The Girl in the Red Coat, Faber & Faber, 2015 (Kindle edition, Chapter 6) When I wake up in the morning everything's wonderful. For a moment I can't understand why. Then I remember: Mum's said if the weather's good we can go to the storytelling festival and that's today. |

Description beats

They help readers understand what characters are wearing, what they look like, what’s surrounding them, what they can hear, see, smell, touch or taste. That brings the scene alive.

|

Example from published fiction

Harlan Coben, Win, Arrow, 2021 (Kindle edition, Chapter 1) His name is Teddy Lyons. He is one of the too-many assistant coaches on the South State bench. He is six foot eight and beefy, a big slab of aw-shucks farm boy. Big T—that's what he likes to be called—is thirty-three years old, and this is his fourth college coaching job. From what I understand, he is a decent tactician but excels at recruiting talent. |

Dialogue beats

Like action beats, dialogue is an opportunity to bring depth to non-viewpoint characters in limited narrative styles. Their internal opinions and feelings – which we don’t have access to because we’re not in their heads – are revealed to us.

Why mixing up beats makes scenes more interesting

Writers and their publishing teams can use the drafting and editing stages to analyse the prose and evaluate whether there’s sufficient balance.

How to analyse a scene for beat balance

Approach 1

One way of approaching this is to think not in terms of the different types of beats but instead in terms of what they contribute, and whether there’s too much or too little.

And so writers and their editors can ask: Which of the following should the reader experience in this scene, and are they present? Here’s a summary of those elements:

- Sensibility (via emotion beats)

- Movement (via action beats)

- Breathing space (via inaction beats)

- Stability (via description beats)

- Expression (via dialogue beats)

An over-reliance on dialogue – even if it’s extremely well written – leaves a reader with no nudges about the emotions characters are experiencing or the environment they’re operating in. It’s two or more talking heads on a page.

If there should be expression in the scene, but the characters are chattering too much, think how you might turn the volume down, or at least disrupt it.

Consider introducing a few action, description and emotion beats. Or even turn some of the information contained within the speech into narrative.

An over-reliance on objective description – even if it gives the reader a rich sense of the environment – leaves readers with no way of accessing mood. It’s a menu of what’s where.

Description should stabilise the scene, not crush it so that it’s as flat as a pancake.

Help readers get under the skin of the characters and their environment by adding emotion or dialogue, or a little action that gives the scene some movement.

An over-reliance on emotion can be draining and doesn’t give the reader the chance to take a breath. It’s like a counselling session.

If there should be emotion, but a character’s self-absorption is swamping a reader’s ability to make sense of the environment, introduce description and action beats to ground the reader a little more objectively.

|

Approach 2

Another option is to colour-code the text in a scene according to what type of beats are in play. This can help authors and editors evaluate whether one type of beat is overbearing, and where they might add in additional types of beat to disrupt that dominance. It's a powerful way of communicating the problem visually and quickly. |

Summing up

Other resources you might like

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level: book

- Fiction editing line craft: books

- How to Line Edit for Suspense: multimedia course

- How to Write the Perfect Editorial Report: multimedia course

- Narrative Distance: multimedia course

- Resource library

- Switching to Fiction: multimedia course

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

1. Understand the different types of editing

The first draft of a book is unlikely to be ready for proofreading. Instead, focus on structure first – so how the story hangs together as a whole.

Next comes stylistic line work that focuses on the flow and rhythm of prose.

Copyediting comes after that. This is the more technical side of the work that looks at consistency and clarity.

Only then is it time for the quality-control stage: proofreading.

Writers who want to know more can watch a video, listen to a podcast episode or download a booklet.

2. Top tools and methods for writers on a budget

- community

- content

- craft books

- courses

- conscious language

Community

Take a look at the Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi) and the Society of Authors. They’re two fine examples of organizations who are dedicated to supporting writers at different stages of their journey.

Membership includes access to free and affordable paid-for events and resources. But they offer something else that’s incredibly valuable too – a network of like-minded people.

Trying to make your mark in the publishing world can feel overwhelming, so being able to get advice and inspiration from others on the same journey is priceless.

Content

There’s a ton of useful – and free – guidance about the craft of writing online, so it’s worth budget-sensitive writers spending time digging around in the search engines. However, those interested in sentence-level guidance can visit my resource library as a first port of call.

I also recommend The Creative Penn, a superb knowledge bank through which Joanna Penn guides aspiring authors on how to write, how to get their books published and how to make their work visible. I love Joanna’s genuine and approachable teaching style, and how she makes self-publishing accessible to everyone.

Craft books

Books are the most affordable way I know of accessing high-quality guidance. There are lots – too many to mention here – but I recommend fiction writers start with The Magic of Fiction by Beth Hill because it pays attention to structure and helps writers create a great first draft.

My own Editing Fiction at Sentence Level focuses on line craft that helps writers refine the flow, rhythm, mood, voice and style of their prose.

And Joanna Penn’s How to Write Non-Fiction takes authors step by step through the whole book-creation process – from mindset to marketing and everything else in between.

Courses

Love learning at your own pace? Online courses are an affordable and convenient way to study in a multimedia environment.

There are lots to choose from. For starters, take a look at Joanna Penn’s business-focused author courses, and for craft-based tuition for fiction, try Narrative Distance: A Toolbox for Writers and Editors and Preparing Your Book for Submission, two courses from my own training stable.

The National Writing Centre also offers online training that aims to build authors’ confidence. Some of their courses are even free. The NWC also partners with the University of East Anglia to provide more in-depth premium creative-writing courses that come with tutor support.

Conscious language

Anyone who’s aware of the events surrounding Kate Clanchy’s Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me will understand the importance of reviewing their work through the lens of representation.

I’m not for a minute suggesting that a work of fiction or non-fiction has to follow a set of prescribed ‘rules’ about what can or can’t be written, but rather that writing means applying the same mindfulness to the words we put on a page as those that come out of our mouths.

When we write, we’re building a relationship with our readers, even though we don’t know who most of them are. And so consciously considering whether our words are helping or harming is just good human practice – one that means our books function as we intend them to, whether that’s to teach or to entertain.

For authors who want a little more guidance on this, I have a free booklet on inclusive and respectful writing. It doesn’t prescribe, just helps writers make informed decisions.

3. Manage your first draft appropriately

Once that’s done, put the book away – just let it sit for a while – then revisit it and decide what’s working and what isn’t, what needs refining, amplifying or deleting.

Perhaps follow Sophie Hannah and Jeffery Deaver’s lead and create detailed outlines that help keep you on track even at first-draft stage. You can read more about Hannah’s method in ‘Why and how I plan my novels’.

If you do decide to work with an editor, invest time in finding someone who’s a great fit for you: someone who gets you and is engaged with what you’re doing with your writing.

That person should also be offering the right level of editing (see 1. Understand the different types of editing).

And tell them if you’re nervous about being edited; it’s perfectly normal to feel that way. Just bear in mind that they’re on your side and are working for you, for your book and for your reader!

4. Understand the difference between style, convention and peevery

Do I have preferences? I do – everyone does – but that’s all they are and they have no business in the work that editors do for their clients. Our job is to focus on a client’s goals, the world of their story, and the readers who’ll come along for the journey.

There are stylistic and grammatical conventions in writing, and a professional editor should understand those and be mindful of them, but editing requires a malleable mindset that respects voice and rhythm as much as anything else.

It’s about sense and sensibility, not prescriptivism and pedantry.

Listen right here to this collection of episodes from The Editing Podcast on language, grammar and style:

5. Recognize the pros and cons of being your own publisher

The main disadvantage is … you get to control everything!

You’re the publisher as well as the writer, which means you decide which books to write and publish, what the cover will look like, which levels of editorial help to commission, which channels to distribute your book through, what the price will be, what formats the book will be available in, and how your promotion strategy will play out.

That’s a lot of work – work that costs you time and money. Publishers will do some of it for you. Still, that will come at a cost because you’ll be taking a royalty that’s likely lower than the return from selling direct.

Being your own publisher isn’t everyone’s wheelhouse, but for those who want to be in control, there’s never been a better time to wear that hat because of all the technical solutions available to authors.

Any writer can use Amazon. It’s the biggest bookstore on the planet. But you might want to sell direct via your website, too, because that’s your very own shop window.

Platforms like Payhip and BookFunnel have made that possible, and it’s made it easy … not just for you but for your customers too.

And for authors who are not only writing but also teaching about writing, there are multiple platforms that support that too – LearnDash (Wordpress plugin), LearnWorlds and Teachable for example.

6. Take control of cramped and communal work spaces

I realize that everyone’s situation is different, but I hope at least one of the following tips will speak to anyone trying to carve out a dedicated work space.

- Agree boundaries in shared spaces: Decide which part is yours and which is theirs, and respect that.

- Create boundaries in multifunctional spaces: Some writers have to work in a bedroom, kitchen or living room. If there’s enough space, fence off a corner with a panelled room divider. These can be pricey so an alternative is to install a rail and fashion a curtain from an old duvet cover or sheet.

- Use mobile desks in cramped spaces: Mobile desks are readily available online and are priced competitively so that even writers on a smaller budget can house a monitor, keyboard, mouse and hard drive. Complement with a storage trolley for your books and stationery. Wheel the whole lot into another room when required!

Summing up

You’re not alone. There’s a ton of help available to help you … whatever your budget and whatever subject or genre you’re writing in. These 6 tips barely scratch the surface, but I hope they at least inspire you to take the next steps of your indie-author journey with confidence.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

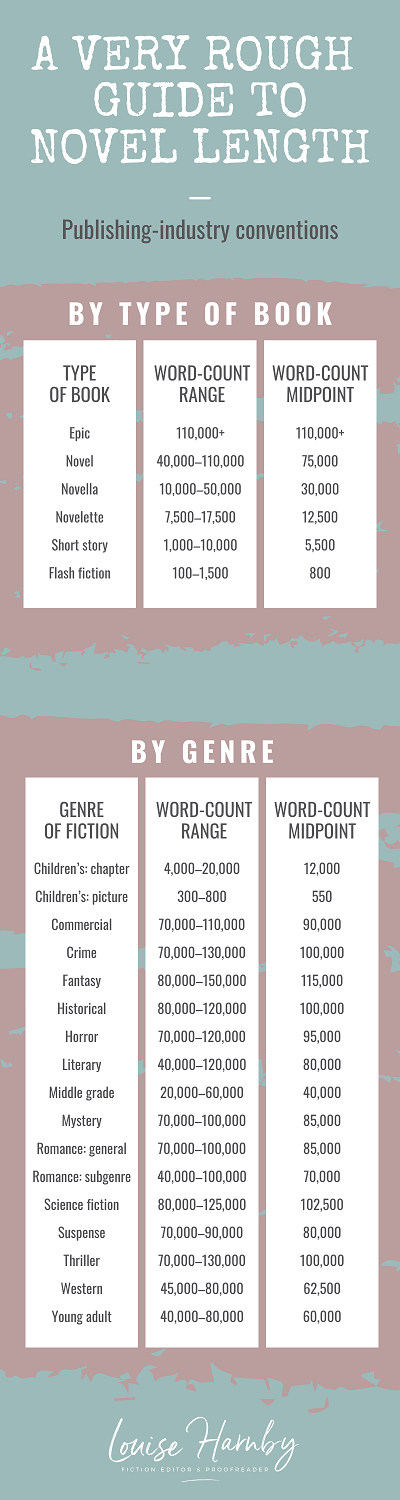

What determines word count?

- type of book

- target age group

- genre

The infographic below provides a very rough guide to word counts – lower and upper limits and a midpoint. These align with publishing convention.

And these are conventions rather than rules, which is why the ranges are rather wide for some genres.

Economics: Printing costs

Bear in mind, however, that your chosen trim size will affect the number of words you or your designer fits on a page and therefore the page count, which in turn will affect printing costs.

It’s therefore worth experimenting with different trim sizes and interior designs if you’re going down the print-on-demand route.

There’ll be an optimal design that offers the desired aesthetic for your budget. Approximate calculations are available via the KDP print cost calculator.

If you’re printing in bulk with your own printer, there might be economies of scale on offer for larger print runs. Talk to the supplier and your formatter about how to keep costs down by tweaking the interior design without impacting on readability.

Economics: Editing costs

If you’re working with a pro editor, remember to factor your word count into your chosen editor’s fee structure.

Expectations: Audience sweet spots

And I don’t mind digging into 100K words or so for Baldacci because his books are quite detailed. Sue Grafton’s Alphabet mystery series has a different feel to it and I’ve come to expect a quicker read – around the 55–75K-word mark.

And if you're self-publishing, consider this from the IngramSpark blog: ‘With less time available for reading, it makes sense that readers want to get to the last page quicker. The trend for the past few years has been to publish books with less than 200 pages on average, or around 50,000 words’ (Self-publishing Trends 2018–2019).

Expectations: Agents and publishers

Hitting an industry-standard isn’t about word count in itself. It’s about ensuring that the story is told with enough words, and only enough words so that readers are engaged.

Paying attention to word-count conventions reduces an author’s chances of ending up in a slush pile because there aren't red flags indicating overwriting if the novel is huge, and undeveloped story if the book's shorter than standard.

Why word counts help authors focus on quality

When the book's too long

If, however, 20K words are cluttering adverbs and adverbial phrases that could be removed or replaced with stronger verbs, the novel’s length isn’t serving the reader.

Or perhaps there are 30K words of laboured stage direction – detail that describes every mundane movement a character makes to remove themselves from a car, climb a flight of stairs, or move from one room to another. Often, nudges that enable the reader to make sense of space and place are enough.

Readers don’t count words, but they will start skimming over them if the prose isn’t tight. And so even if your first draft has X,000 words, use the revision stage to consider what needs to be removed or tweaked.

When the book's too short

If your novel’s word count is substantially lower than industry conventions, consider what might be missing. There could be structural issues such as a too predictable plot, undeveloped character arcs, or too few obstacles.

There could also be opportunities to show rather than tell a scene so that the narrative distance decreases and the reader is drawn deeper into character experience.

The difference between word count and page count

Pro formatters can adjust the page count of a printed book by tweaking the design, though there are limitations.

No reader will be convinced that they’re holding an 80K-work crime novel just because 50K words are set in a Times New Roman 18.

On the other hand, if you’ve written 100K words aimed at the middle-grade market (8–12 years), you’d be wise to reduce the word count considerably rather than asking your designer to make your book look shorter by squeezing more words on each page!

Furthermore, when it comes to ebooks, there’s no such thing as a standard page because the reader controls how much text appears on the screen. Ebooks lengths are therefore measured in kilobytes (KB), not pages.

Summing up

Pay attention to word counts as part of an evaluation process that ensures the words that need to be on the page are on the page, and those that needn’t be there are removed. That way, your story will be in the best shape for your readers.

Related resources for authors

- Author resources library

- Blog post: 6 ways to improve your novel right now

- Blog post and video: Crime fiction subgenres: Where does your novel fit?

- Book: Editing Fiction at Sentence Level

- Blog post: Playing with sentence length in crime fiction. Is it time to trim the fat?

- Book: Making Sense of ‘Show, Don’t Tell’

- Blog post: Unveiling your characters: Physical description with style

- Blog post: Using adverbs in fiction writing

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

FIND OUT MORE

> Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

> Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

> Learn: Books and courses

> Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Listen to find out more about

- Writing a series vs standalone novels

- Tips on developing a coherent series

- Starting afresh with a new set of characters in a new environment

- Top creative-writing tips for beginner author

- Recommended writing-craft resources

- Back-cover blurb and Amazon blurbs

- Cover design

Here's where you can find out more about Andy Maslen's thrillers.

Dig into these related resources

- Author resources

- Book: Editing Fiction at Sentence Level

- Blog post: 3 reasons to use free indirect speech in your crime fiction

- Blog post: Crime fiction subgenres: Where does your novel fit?

- Blog post: How to write dialogue that pops

- Blog post: Playing with sentence length in crime fiction. Is it time to trim the fat?

- Blog post: Writing a crime novel – should you plan or go with the flow?

- Podcast episodes: The indie author collection

Music Credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Listen to find out more about:

- Story basics: the Plot Accelerator

- Why developmental/structural editing comes after book coaching

- Genre, viewpoint, tense, character motivation and conflict, plot and subplot, and character arc

- Book mapping, and avoiding drinking and thinking!

- Super critiques on steroids: making a story solid

- The dynamics of book coaching

- Most common problems authors face

- Super-critiques

Contacting Lisa Poisso

- Email: [email protected]

- Website

- Blog

- Twitter: @lisapoisso

- Instagram: lisapoisso

- Clarity newsletter

Editing bites and other resources

- Moniack Mhor, Creative Writing Centre, Scotland

- Start writing fiction: Free Open University course

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Listen to find out more about ...

- An overview of what developmental editing includes

- Critiques as big-picture evaluation

- Who benefits from developmental editing and critiques

- Where developmental editing and critiques fit into the editing process

- Whether an author needs to hire a specialist editor for developmental editing

- Writing coaching versus developmental editing

- The difference between story and plot

- Story structure – planning versus revision

- Story structure – conscious deviation from traditional three-act structure

- Story structure – momentum

- Narrative style

- Subplots – when they work and

- How theme can hold a story together

More about Sophie

- Sophie Playle, Liminal Pages

- Sophie’s editing courses

- Email: [email protected]

- Twitter: @sophieplayle

- Facebook: facebook.com/liminalpages

- LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/sophieplayle

Resources mentioned in the show

- How to Write a Query Letter – Everything You Need to Know’, Sophie Playle

- ‘How to Write a Synopsis – Everything You Need to Know’, Sophie Playle

- Write a Great Synopsis: Nicola Morgan

- Developmental Editing: A Handbook for Freelancers, Authors and Publishers: Scott Norton

- Poetics, Aristotle

- Masterclass: David Mamet Teaches Dramatic Writing

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Find out more about

- The writer’s responsibility to the reader and the story

- Story events and character reactions in relation to plausibility and authenticity

- Salvation events

- Unnatural character realizations

- Contrived plot turns

- Thematic insertions or digressions

- Turning unearned writing into earned prose

- Idea flow in non-fiction

Resources related to the show

- Title Case Converter

- The Allusionist podcast

- Storm Writing School

- Free course from Tim: The Gold Standard Scene: Analyses of Near-Perfect Scenes in Prose Fiction

- Storm Writing School on Twitter

- Storm Writing School on Facebook

- Storm Writing School on Pinterest

- Writing resources from Louise

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

In July 2018, I wrote my first piece of flash fiction and submitted it to the Noirwich Crime Writing Festival’s flash fiction competition. Here’s what I learned.

Think of a tiny story that packs a large wallop … that’s flash fiction. It’s not always called that. Some call it micro fiction, others nano fiction. I’ve also heard it called the shortie, short-short and postcard fiction.

How long is it? There’s no consensus other than it’s short ... very short. Some types of flash fiction have established word counts – the dribble with 50 words, the drabble with 100 words, and Twitterature – no more than 280 characters. If Twitterature seems like a challenge, imagine writing it when the character-count limitation was 140!

So what are the key components and what can they teach writers of longer-form fiction?

1. Brevity – making every word count

Keeping things tight is one of the biggest challenges faced by many of the beginner novelists I work with.

Overwriting usually occurs because the author hasn’t yet learned to trust their reader. Will that single adjective be enough? Maybe another sentence that says a similar thing would be in order, just for clarification …

Often, it’s not a reflection of a writer’s ability to write, but about confidence. Getting the balance right comes with experience and not a little courage. A line editor can help with overwriting – they bring fresh eyes to the book, and can advise on what can safely be removed without damaging flow, sense, rhythm and tension, and in a way that respects style and voice.

Flash fiction helps writers practise the art of precision in the extreme. And when it comes to self-editing your novel, you can ask yourself this: ‘If this were a short story and my word count was restricted, is this the way I’d construct this sentence?’

The answer might be ‘No, but I’d be missing an opportunity to enrich the narrative and the dialogue in a way that’s best for my book.’ That’s a great answer. Still, the flash fiction writer is forced to be disciplined, and when it comes to writing longer works, that discipline will get you used to thinking in terms of making sure every word counts, and comfortable with removing those that don’t.

A limited word count also encourages writers to experiment with literary devices such as free indirect speech, sentence fragments, action beats, and asyndeton, all of which can facilitate brevity but enrich tension, immediacy, mood and rhythm.

Stories need structure. No writer wants to get to the end of their novel only to realize that the denouement occurred ten chapters earlier. Sophie Hannah calls it ‘story architecture’, which I think is both a practical and a beautiful way of thinking about how a writer helps their readers experience a novel.

There are different ways to shape stories but the most common is the three-act structure. First, the beginning or hook that draws us in. Second, the middle where the confrontation takes place. This is where we come to understand the characters’ motivations and the conflict or obstacles in their way. Third, is the end where the denouement or resolution occurs.

Says Julia Crouch, ‘If you have any storytelling bones in you at all, you will more than likely, even subconsciously, end up with a structure like this.’

How does flash fiction help? Do you even need to worry about structure when you’re writing such a short piece of work?

Absolutely! No one will enjoy an 80,000-word novel that’s poorly structured. The same applies to 800 words. The only difference is that with flash fiction they’ll lose interest quicker.

Flash fiction is a story form in its own right. It’s not about pulling an excerpt from a longer-form piece of writing. Flash must have structure – a beginning, a middle and an end. Something must happen to someone or something, and readers must leave the story feeling satisfied, that the story is complete, that they’ve been on a journey, albeit a short one.

Without structure, it will descend into nothing more than an extract.

Perhaps flash is akin to poetry – squeezing big ideas into small spaces. That too, though, is good practice for the novelist, because it encourages writers to think about the discipline of shaping, and the journey that the reader will be taken on.

There’s nothing more disappointing than a book that hooks you into turning page after page only to sag into a giant anti-climax.

‘Endings are so important to the reader and you will never please everyone,’ says Nicola Morgan. ‘Readers do want the end to feel “right”, though. They have spent time with these characters and they care what happens to them.’

How and when novelists decide to tie up all or most of the loose ends will depend on style, genre, and whether the book is part of a series, but there must be some sort of closure so that your readers aren’t left hanging.

Flash fiction is a challenge to write, but it’s a challenge to read too, particularly for those who love to get stuck into a world and the characters who move around within it.

It’s therefore an excellent format in which to practice packing a final punch, even if that amounts to just one or two sentences. This form of writing also allows writers to play with readers’ expectations of resolution in quirky ways.

You might decide to evoke a laugh, or a shudder, or shock, or a sense of poignancy, but the reader should feel something such that even though you’ve only written a few hundred words the story is memorable.

Here are some additional tips that you might consider if writing flash fiction appeals.

Which tense will you use?

At the time of writing, I’ve written eight flash fiction stories, none of more than 900 words. In all but two I instinctively opted for the present tense. I didn’t notice my predilection until I reread them one after the other. It made me reconsider the two I’d framed in the past tense. I decided to see what would happen if I changed them.

I learned something. My narrative tension loses its piquancy when I write in the past. That’s not to say I wouldn’t use the past if I were writing a novel. However, for flash fiction, there’s no time to lose! I’m trying to close the distance between the reader and the viewpoint character so that the former is quickly immersed in the tiny world I’ve built.

The opposite might be true for you; there are no rules. But if your flash is flagging, don’t be afraid to experiment with tense and evaluate the impact.

Flash fiction tips #2: Characters and viewpoint

Given the space available, keep the story tight by sticking to one viewpoint character.

It’s easier to create immersion if you allow readers to get under the skin of a single person’s experience. That doesn’t mean there can’t be other characters in the frame, just that we see these others through the viewpoint character’s eyes.

You’ll likely need to omit anything about the character that isn’t necessary to drive the story forward. Novels include descriptions of the characters’ appearance and personality so that we can better visualize them and understand their motivations.

With flash, consider focusing only on those unique physical and emotional traits that nudge the reader towards the big reveal.

Flash fiction tips #3: Use the mundane

Play the what-if game. Take an object, or place, or personality attribute of someone you know, and ask what the story might be in another universe.

What if that old door in your friend’s hallway didn’t really go to the downstairs loo? What if that scribble you found on the inside of a library book had a more sinister connotation? What if your neighbour wasn’t quite who you believed them to be? What if your best mate’s boring job was just a cover story?

Sometimes the most wonderful clues to the theme of a shortie are hidden in plain sight.

4. The editor turned fiction writer – lessons learned

Writing and editing are two very different arts. I don’t believe that a good fiction editor must be a fiction writer. I do, however, think we need to understand the core components of fiction writing and what makes a book work, and be able to place ourselves in the shoes of the author and the reader.

Still, I’m (now) one of many fiction editors who also write fiction. Some of my colleagues have publishing contracts. Some are self-publishers. Some have agents, while others are seeking representation. Some of us write our fiction purely for pleasure.

There are many roads, but we all agree on one thing: it has been good for us to sit on the other side of the desk – to be the writer, to be the one being edited.

- I’ve written non-fiction – several books, materials for online courses, this weekly blog, guest articles for magazines and newsletters, essays during my university days. But I’d not written fiction since I was in high school, and back then I wasn’t being judged on it.

- The brief was to write 500 words of crime fiction related to Norwich or Norfolk. The last time I wrote anything with fewer than 500 words was when I constructed the bio on my website!

The amazing thing is that I made the final shortlist of three.

That, however, presented a new challenge. I was invited to Noirwich Live where the winner would be announced by New York Times bestseller Elizabeth Haynes. Would I read my story ‘Zeppelin’ to a roomful of people, mostly complete strangers?

The audience comprised fellow amateur writers, teachers of creative writing, published writers including Haynes, Merle Nygate and Andrew Hook, and most important of all, my daughter Flo and dear friend Rachel.

My knees might have been trembling as I took to the floor, but I got the job done and thought about what I’d learned from the experience.

Sharing takes courage

Writing fiction is one thing; sharing it with others is quite another. Even tiny fiction like mine. For some of us, it takes courage, especially when massive doses of newbie impostor syndrome are flowing through one’s veins.

And this is exactly how many of my author clients feel. Sometimes I’m the first person on the planet to see their work when they’re done with it. My experience enhanced my already deep respect for them, because now I know how it feels to share my fiction with others.

Editing is an honour

My own small venture has taught me what a privilege it is to be chosen by an author to edit for them. When they choose me or one of my colleagues, they take a leap of faith. They place trust in us to treat their words with respect and help them move forward towards their publishing goals.

Fiction is intimate

The nine stories I’ve written to date are really short. I’m at the beginning of my fiction writing journey. I have a lot to learn. But those stories are precious to me. Every one of them contains a bit of me, or of someone I care about, or someone or something that has made a mark on me in some way. They are not fact, but they are not completely made up either, and that infuses them with a level of intimacy.

In other words, fiction writing is personal.

It’s important that the fiction editor takes all of that into their editing studio and remembers it at every touchpoint of the project – an amendment, a query, a summary – and never forgets to say thank you.

|

FREE EBOOK

If you'd like to read my Noirwich shortlisted story and some additional quirky tales, help yourself to this free ebook. Click on the button below to get your copy. Please note that these stories contain profane language and violence. |

Further reading

- Julia Crouch. Five tips for keeping your readers gripped. Noirwich. 2018.

- Louise Harnby. 3 reasons to use free indirect speech in your crime fiction

- Louise Harnby. Playing with the rhythm of fiction: commas and conjunctions

- Louise Harnby. Playing with sentence length in crime fiction. Is it time to trim the fat?

- Louise Harnby. Shorts and Flashes. 2018

- National Centre for Writing

- Nicola Morgan. Write to be Published. Snowbooks. 2014

- Noirwich Crime Writing Festival

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

My brushes with the law have been limited to bad parking. Still, I know a few coppers socially, and it’s to them I’d head for procedural guidance in the first instance.

If you know a police officer, a forensic anthropologist, a crime-scene investigator, a barrister, or whatever, ask them if you can pick their brains. They’ll have expert subject knowledge and insights, and your talking with them face to face could be the most powerful tool of all.

If you don’t have existing contacts, ask your friends for theirs or put a call out on social media. A writer recently requested help from munitions experts via the Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi) Facebook group. Several commenters provided advice and one offered to put her in touch with an expert.

If your book's set in the UK, try Consulting Cops or Graham Bartlett, author and crime fiction advisor. Both have teams of law-enforcement experts who'll help you keep your facts straight.

Here’s crime writer Julie Heaberlin discussing the importance of researching and feeling comfortable approaching experts, especially to bring deeper layering to her novels:

How to Write Crime – Harry Brett in conversation with Sophie Hannah and Julia Heaberlin. Waterstones, Norwich, 2018

Search online using the keywords ‘ride-along police [your country/state/city]’ and see what comes up.

How about TV and movies? Your favourite crime dramas and fiction might have been meticulously researched. Then again, they might not. In ‘Five Rules for Writing Thrillers’ David Morrell urges writers to do the research but to use caution:

Morrell talks more about how research makes him ‘a fuller person’ and how he learned to fly in order to create an authentic pilot for his book The Shimmer. The expense of a pilot’s licence will probably be out of reach for the average self-publisher. YouTube could be the solution.

And there are lectures on the science of blood spatter, computer forensics, investigation techniques, and forensic imaging. You name it, it’s probably there.

Wikipedia is great for any sleuthing writer wanting to track down information about criminal procedure. Do, however, use the primary sources cited in the references to verify the information. In the online masterclass ‘How to Write a Crime Novel’ Dr Barbara Henderson recommends using at least two sources for internet-verification purposes.

Here are some searches to get you started:

Visit the official site of MI5. There’s information on how it handles covert surveillance, communications interception, and intelligence gathering, plus a brief overview of its history since its creation in 1909.

Christopher Andrew’s The Defence of the Realm is the first authorized history of the service. Published by Penguin in 2010, it’s available on Amazon and in major bookstores.

Visit The National Archives and type MI5 into the search box. That will give you access to all the files that have been released into the public domain to date.

National Crime Agency (UK)

The NCA is tasked with protecting UK citizens from organized crime. Its website has articles and reports about cybercrime, money laundering, drugs and firearms seizure, bribery and corruption, and trafficking.

I recommend looking at the NCA’s free in-depth but readable reports such as the National Strategic Assessment of Serious and Organised Crime 2018, which outlines threats, vulnerabilities, the impact of technology, and response strategies.

MI6 (SIS) – the UK’s secret intelligence service

Visit the official website of the SIS to find out how it handles overseas intelligence gathering and covert operations. There’s a brief overview of the service’s history and some vignettes that illustrate how intelligence officers operate.

Keith Jeffery’s MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909–1949 is ‘the first – and only – history of the Secret Intelligence Service, written with full and unrestricted access to the closed archives of the Service for the period 1909–1949’. If you want historical information, this is a good place to start.

GCHQ – Government Communications Headquarters (UK)

The GCHQ website is worth visiting just to see the building from which it operates in Cheltenham! There’s an overview of GCHQ history, operations, its various operational bases, and how it works with Britain’s other security services to manage global threats.

For a more in-depth study of the service, start with Richard Aldrich’s GCHQ: The Uncensored Story of Britain's Most Secret Intelligence Agency.

FBI – Federal Bureau of Investigation (USA)

The FBI’s website is packed with the usual overview material of how and why, but I think the go-to resources are the likes of the free Handbook of Forensic Services, the Terrorist Explosive Device Analytical Center (TEDAC) page, and the training guidance.

The easiest way to navigate around the site is to head to the FBI home page and scroll down to the links in the footer.

NSA – National Security Agency

The NSA website is the place to go for twenty-first-century code-breaking information, and there’s a ton of information about cybersecurity and intelligence. Head for the Publications section to get free access to The Next Wave and various research papers. The material is dense but could be just the ticket for building backstories for cybergeek characters.

Michael O'Byrne is a former police officer who worked in Hong Kong, and later with the Metropolitan Police (sometimes referred to as New Scotland Yard). Try the second edition of his Crime Writer's Guide to Police Practice and Procedure.

INTERPOL

This is the world’s largest police force with nearly 200 member countries. The Expertise section of its website is rammed with useful and readable information on procedure, technical tools, investigative skills, officer training, fugitive investigations, border management and more.

UK police forces

Police procedure will vary depending on where you live. You can access a list of all UK police force websites here: Police forces, including the British Transport Police, the Central Motorway Policing Group, the Civil Nuclear Constabulary, the Ministry of Defence Police and the Port of Dover Police

An Garda Síochána – Ireland’s national police and security service

The easiest way to navigate the Garda’s website is to head for the home page and scroll down to the sitemap at the bottom. There you’ll find links to information on policing principles, organizational structure, and the history of the service. The Crime section is particularly strong on terminology and procedure.

Legal resources

Lawtons Solicitors’ website has an excellent Knowledge Centre filled with articles on parliamentary acts, offences, criminal charges and police procedure. What are the drug classifications in the UK? and Police Station interviews are just two examples.

Ann Rule’s advice on attending trials is aimed at true-crime writers, but you could use the guidance for fictional inspiration: Breaking Into True Crime: Ann Rule’s 9 Tips for Studying Courtroom Trials.

Crown Prosecution Service (UK): The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) website provides detailed prosecution guidance for criminal justice professionals. It is extremely dense, and so it should be; it wasn’t designed for novelists! See, for example, the section on Core Foundation Principles for Forensic Science Providers: DNA-17 Profiling. Still, there’s a wealth of information there for those prepared to wade through it.

Department of Justice (USA): The DOJ site offers guidance on the role of the Attorney General, the organizational structure of the department, lots of statistical information, and maps of federal facilities.

- Forensic Science and Beyond: Authenticity, Provenance and Assurance is a free, huge and fascinating study that includes evidence and case studies of forensic science in relation to cybercrime, chemical weapons, victim identification, pharmaceuticals, nuclear forensics, and more. It’s worth a read for plot ideas as much as procedure.

- The Crime Scene Investigator Network claims to be ‘the world’s most popular crime scene investigation and forensic science website’. It’s US-centric, so whether the procedures outlined there will be relevant to your jurisdiction will be worth checking.

Still, the site is easy to navigate and avoids academic jargon. There’s information on evidence collection (blood, semen, firearms residue, drugs, fingerprints, fibres, and so on), photography and procedure, and a collection of articles written by crime scene investigators. Well worth visiting, wherever you’re based. - If you want to know what the UK’s Forensic Science Regulator considers best practice, delve into its current Codes of Practice And Conduct, 2017 and The Control and Avoidance of Contamination in Crime Scene Examination involving DNA Evidence Recovery.

- For additional technical guidance, and to search for more forensics resources, visit the UK government’s Publications and search by keyword. What’s especially useful about these collections is that archived reports are held on file. And that means you can access guidance not only as it stands now, but in the past too.

- The Royal Anthropological Institute has a Code of Practice for Forensic Anthropology that ‘defines the purpose of the forensic anthropology process and the series of steps that must be followed from the time a forensic anthropologist (FA) is notified of involvement in a case until the presentation of findings, whether by report alone or through the provision of evidence in the court room’.

- There are some interesting insights into human taphonomic research (that's body farms to you and me) in this report: The Operation of Body Farms – Learning Points for Setting up a Human Taphonomy Facility in the UK.

- Val McDermid's Forensics: The Anatomy of Crime, published by the Wellcome Collection in 2015, 'traces the history of forensics from its earliest beginnings to the cutting-edge science of the modern day'.

- Introduction to Forensic Science: This is a free online course from the University of Strathclyde via FutureLearn. 'Explore the methods underpinning forensic science, from crime scene investigation to reporting evidential value within a case.'

- Victorian Crime & Punishment includes a prisoner database and case studies of real crimes and trials.

- The National Archives holds historical records of serving officers in the Metropolitan Police and the Royal Irish Constabulary.

- The Police History Society documents police museums, collections, historical societies and related resources.

- US crime writer Jason Lucky Morrow hosts a true-crime blog called Historical Crime Detective. The subtitle is ‘Where Old Crime Does New Time’. That in itself was enough to pull me in! He promises we ‘will discover forgotten crimes and forgotten criminals lost to history. You will not find high profile cases that have been rehashed and retold ad infinitum to ad nauseam.’

- Harvard Injury Control Research Center's web pages related to firearms research offers a wealth of information on gun-related, accidents, ownership, carrying, and bad science.

- Guns Guns Guns is an ‘online directory and forum for those who prize their right to keep and bear arms’. If you want to know something about firearms, the answer’s probably there.

- The Firearms section of the UK government’s website includes statistics on firearms certification and guidance on legal use.

- The ATF: Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (USA) includes a photo gallery of different categories of guns, a code of federal regulations, licensing information in regard to firearms and explosives, and articles about tools and services for law enforcement.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

So what do some of the big-name crime writers have to say on the matter?

What’s right for you?

‘The more I talk to other crime writers the more I start to become fairly sure that for each writer there is an ideal way, but there isn’t one ideal way,’ says Sophie Hannah.

I think I’ve read everything Harlan Coben’s ever written. If I haven’t, it’s waiting in the pile or on the Kindle. If you’d asked me, I’d have marked him as a planner. His stories hang together so well; he ties up every loose end. And I always have that ‘Ah, that’s what happened’ moment. But in fact, Coben’s a pantser:

Maybe you’re like him or Julia Heaberlin:

Or perhaps you’re like Susan Spann:

Or Hannah:

To help you decide whether to plan or pants, consider the following:

- Will planning impede your creativity?

- How fast do you write?

- When do you want to find out whether your plot works?

- Are you a linear or a non-linear writer?

- How will you decide where to plant your clues?

- How will you ensure your story has a cohesive structure?’

Some writers fear that planning will mute their creativity and the process of discovery. The following excerpt is from an article from the NY Book Editors blog:

Heaberlin feels that surrendering control to her characters is essential to the creative unfolding of her stories:

However, passionate planners feel differently. Their plans are as much a form of artistry as the actual writing. Here’s Hannah on how a plan needn’t thwart spontaneity:

Some authors write multiple drafts to ensure the book’s plot works. That slows down the process. Hannah’s detailed planning approach means her first draft works; she’s already identified where the problems are before she gets started on the actual writing process.

Jeffery Deaver concurs:

He then walks around talking to himself, deciding where on the whiteboard the clues need to go so that the main plot and various subplots will work. And if he finds that a clue won’t work in a particular place because, say, character X doesn’t know Y yet, he moves the post-it note. It’s an eight-month process but once it’s done, ‘writing comes quickly’.

Still, don’t get too comfy! Andy Martin spent the best part of 12 months in the company of Lee Child as he wrote Make Me:

Which just goes to show that being a pantser doesn’t necessarily mean being a slow writer.

If you’re a pantser, the idea of finding yourself stuck in a hole after months of writing might not terrify you. Lee Child doesn’t let it stop him.

In an interview with Harry Brett, Heaberlin acknowledges the need for third-party assistance to fill in the gaps and polish her stories:

Contrast that approach with those of these two planners:

Hannah: ‘Without a start-to-finish plan of what’s going to happen in my novel, I don’t know for certain that the idea is viable. It’s by writing a chapter-by-chapter, scene-by-scene synopsis that I put this to the test. I’d hate to invest years or even months in an idea I suspected was great, and then get to where the denouement should be and find myself thinking, “Yikes! I can’t think of a decent ending!”’

What kind of writer are you?

In an interview with Henry Sutton in May 2018, Deaver discussed how planning can help the non-linear writer:

So Deaver’s method allows him to concentrate on telling the part of the story he wants to tell when he wants to tell it.

For every writer who frets at the thought of not knowing where they’re going, there’s another for whom that’s a thrill. Child is a linear writer, and Zachary Petit thinks that ‘very well may be the key to his sharp, bestselling prose’.

If you too enjoy sharing the rollercoaster ride with your protagonist, pantsing could be the best way for you to tell your story. If not, detailed planning might suit you better.

Clue planting

Spann has a two-handed strategy for planning. And it’s all to do with the clues.

The first outline – the one that will determine what she writes – needn’t be particularly detailed. It’s a map of each scene, and each clue, that enables her to keep her sleuth on track.

Just as important, however, is the other outline:

I like her on- and offstage approach, and I think it’s particularly worth bearing in mind if you’re a self-publisher who’s not going to be commissioning developmental or structural editing.

What you don’t want is to go straight to working with a line or copyeditor and have them tell you your clues don’t make sense, because you’d be paying them to paint your walls even though there are still large cracks in the plasterwork.

That offstage outline could help you to complete the build before you start tidying up.

One thing’s for sure: whether you choose to plan or pants your way through the process, put structure front and centre. Recall my comment above about how Coben always leaves me feeling like he must have had everything worked out from the outset. That’s because however he gets from A to B, he understands structure.

Pantsing isn’t about ignoring structure, but about shifting the order of play. Says Deaver:

And here’s domestic noir author Julia Crouch to wrap things up for us:

Good luck with your planning or pantsing!

Further reading

- Andy Martin. The man with no plot: How I watched Lee Child write a Jack Reacher novel. The Conversation. 2015.

- Harlan Coben. FAQ.

- How to write crime – Harry Brett in conversation with Sophie Hannah and Julia Heaberlin. Waterstones, Norwich. 2018.

- Jeffery Deaver – The cutting edge. Henry Sutton in conversation with Jeffery Deaver. National Centre for Writing. 2018.

- Julia Crouch. Five tips for keeping your readers gripped. Noirwich. 2018.

- NY Book Editors. Planning to outline your novel? Don’t.

- Sophie Hannah. Why and how I plan my novels. 2018.

- Susan Spann. 25 things you need to know about writing mysteries. TerribleMinds: Chuck Wendig. 2013.

- The different levels of editing: Proofreading and beyond. Louise Harnby. The Parlour, 2011.

- Zachary Petit. Lee Child debunks the biggest writing myths. 2012.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

If you'd prefer to watch a video, scroll down to the bottom of the article.

There’s crossover certainly and, depending on the commentator, crime fiction gets chopped up into subgenres variously.

I’ve elected not to focus on inverted-detective fiction, heists and capers, LGBTQ mysteries, feminist crime fiction, or romantic suspense, but these subgenres and more all have their place in the market.

One thing’s for sure: ‘Crime fiction is never static and never appears to be running out of ideas,’ says Barbara Henderson.

Two more reasons to know your subgenre

If you’re going it alone, one of your publishing jobs will be to help your readers find your book. When you upload to Amazon, Smashwords or any other distribution platform, you’ll need to decide which BISAC headings to place your book under.

And if you’re going down the traditional publishing route, identifying your subgenre(s) will help a literary agent understand which publishers have a best-fit list and where in a bookstore your novel will be shelved.

If the fit isn’t obvious to you, it could be harder to convince your agent that your book’s marketable.

Ultimately, though, it's the writing that needs to be top-notch, not strict conformity to one or another subgenre. These days, it's probably harder to find crime fiction that isn't fusion of subgenres!

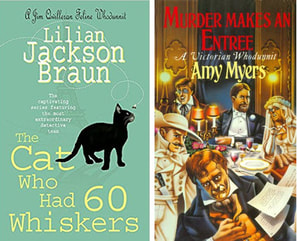

What distinguishes the cosy? Murder yes, but leave out the gore, the pain, and depressing social commentary. Your protagonist might well be flawed but no more so than anyone else in the novel, and your readers will embrace your hero’s quirkiness with a skip in their step.

That doesn’t mean the cosy isn’t tight on plot and well-paced action that drive the novel forward. Contemporary readers want fantastic mysteries with twists and turns that will keep them guessing.

Cosies can be liberating for the playful crime writer who wants to explore the genre with non-traditional characters placed in non-traditional settings:

- Agatha Raisin is a former PR agent who moves to a village in the Cotswolds.

- Amy Myers’ Auguste Didier Mysteries feature a Victorian master chef cum sleuth.

- Lilian Jackson Braun’s The Cat Who … Mysteries feature Jim Qwilleran and his sleuthing cat Koko.

- Nancy J. Cohen’s Bad Hair Day Mysteries feature a beauty-salon owner.

The Golden Age introduced ‘rules’ for the genre. Reba White Williams summarizes these as follows:

- All the clues available to the investigator must be available to the reader.

- There must be a body and we must be introduced to it quickly.

- The perpetrator can’t conveniently appear out of nowhere in the finale.

- The crime must be solved by deduction rather than coincidence.

- There must be multiple clues that can be interpreted in a variety of ways, and more than one suspect.

- Details must be accurate.

See also the quote further down from Otto Penzler about locked-room mysteries – no cheating with doubles and magic!

Today’s authors must abide by the same rules, no matter whether their tales are set in Oxford with Morse, LA with Bosch, or Reykjavik with Erlendur.

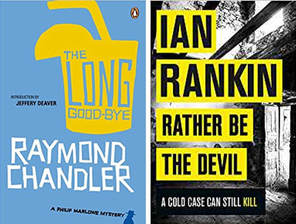

That’s a quote from Raymond Chandler in conversation with Ian Fleming in 1958. Chandler’s response was to write crime fiction that was gritty, depressing, violent, cynical and seedy.

Hardboiled crime writing, as it came to be known, pulls no punches. The protagonists aren’t invulnerable superheroes. And the environments within which they operate are those of contrast – urban decay and tourist hotspots, hope and corruption.

If your crime writing falls into this category, don’t set an amateur protagonist sleuth alongside foolish law-enforcement officers who have neither brains nor access to detection resources.

Hardboiled isn’t pretty but it’s rich in believability. Plots are fattened with complex characters, social commentary and, of course, murder.

Says Matthew Lewin on the contemporary hardboiled crime fiction of James Lee Burke and James Ellroy:

Think Harry Bosch. Tim Walker refers to his creator Michael Connelly as ‘the modern Raymond Chandler’. ‘Connelly says he still sees it as a duty to acknowledge the social climate in his novels’.

Think also Rebus; Ian Rankin, like Connelly, fuses hardboiled with police procedural masterfully.

With hardboiled, even when the crime is solved, your readers won’t expect to close the book feeling that everyone will live happily ever after.

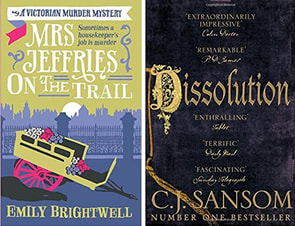

The genre is as interesting for its criminal investigations as for the lessons in social history afforded to the reader. And because the reader needs to understand the historical setting, these novels are often long.

Sansom’s Dark Fire comes in at a whopping 600-plus pages. I have the hardback version and I’m sure I bulked up my biceps just carrying the book from Waterstones to the car park.

If historical fiction floats your writing boat, be prepared to put in the research. Many of your readers will know their history so you’ll need to dig deep.

It’s no accident that the protagonists in these novels are curious renegade monks, lawyers, scholars and the like. The criminal justice system as it exists in our era bears little resemblance to that in these bygone days. Consider the following:

- How did the law work in your time period and location?

- Where did power reside? With the church, the monarchy, the government, or the military?

- What obstacles would your protagonist have been up against? Think gender, access to education, and class boundaries for starters.

- Would your antagonist have had an easier ride than a contemporary baddie? Think modern forensics, technology, transport, communications and socio-economic factors.

Some historical fiction is cosier and shorter. Consider David Dickinson’s Lord Powerscourt and Emily Brightwell’s Mrs Jeffries. These Victorian mysteries offer plenty of intrigue and good old-fashioned murder, but we’re spared the grisly details.

Don’t be surprised to see this lighter crime fiction splashed with a dose of humour as the authors cast their gaze over the social-economic and gender disparities typical of the era.

Still, if the Regency or Victorian cosy is your bag, you’ll still need to gen up on period details.

Here are some examples:

- John Grisham (A Time to Kill, The Runaway Jury) is a former criminal lawyer.

- Kathy Reichs (Déjà Dead, Bare Bones) is certified by the American Board of Forensic Anthropology.

- Robin Cook (Coma, Godplayer) is a trained medical doctor.

That old trope of writing what you know comes into play here and it’s a good reminder that using your own specialist knowledge to bring authenticity to your crime writing makes good sense. And if you’re not a former cop, doc or lawyer but you have friends who are, be sure to pick their brains.

In particular, research the role of your legal or medical protagonist and ensure that the powers of investigation you assign to them are appropriate for their location.

Even if you’re pushing the boundaries of existing science, to give your reader the best experience the foundations will need to be solid.

A locked-room novelist is the illusionist of crime writing, the creator of ‘impossible’ fiction. And yet not so impossible as it turns out, as our brilliant protagonist gradually reveals all.

Take care though. No cheating is allowed with locked-room crime. Says Otto Penzler:

Well-known examples include:

- And Then There Were None: Agatha Christie

- The Hollow Man: John Dickson Carr

- The Murders in the Rue Morgue: Edgar Allan Poe

The artistry of the locked-room mystery lies in the author’s ability to deliver a reveal that doesn’t rely on a device that doesn’t exist in real life, that doesn’t require information to be deliberately withheld from the reader, and isn’t so obvious as to be deducible at the beginning of the story.

I recommend The Locked-room Mysteries, Penzler’s superb anthology for aspiring locked-room crime writers who want to see masters at work. It's huge – over 930 pages – and heavy, but literally worth its weight.

- Harry Bosch: detective (Michael Connelly)

- Jenny Cooper: coroner (MR Hall)

- John Rebus: detective (Ian Rankin)

- Kay Scarpetta: medical examiner (Patricia Cornwell)

- Kurt Wallander: detective (Henning Mankell)

- Lincoln Rhyme: forensic consultant (Jeffery Deaver)

- Temperance Brennan: forensic anthropologist (Kathy Reichs)

Procedurals are notable for their thoroughly researched and authentic rendering of detection, evidence-gathering, forensics, autopsies, and interrogation procedures in order to solve the novel’s crime(s).

Wowser tools and tech don’t come at the cost of strong characterization though. Rhyme is paralyzed following an on-scene accident. Cooper is recovering from the breakdown of her marriage. Rebus has a history of trauma dating from his former military career. Wallander has diabetes, and his daughter attempted suicide in her teenage years.

These in-depth backstories provide complexity and conflict – a kind of layering that fattens the plot without complicating it.

I find Cooper a little whiny, Rebus grumpy, Scarpetta arrogant, Wallander depressing. That doesn’t stop me falling in love with them though. In fact, flawed characters can balance the sterility of the procedural details.

And you, the writer, might find a protagonist with foibles more enjoyable to write. Mankell did:

‘When you’re writing spy fiction you have one overriding goal: to keep the reader turning the pages,’ says Graeme Shimmin.

Here’s some great advice from Kathrine Roid: Don’t wing it when it comes to plot:

If you’re wandering into spy-fi territory, you’ll have a little more freedom to play with gadgetry. If you’re keeping it real, do the research. Know your guns and your gear so that your protagonist doesn’t end up more tactifool than tactical.

But old on a mo. Your spy crime fiction doesn’t have to be a sprint like Robert Ludlum’s or Clive Cussler’s. Mick Herron is one of my favourite writers. The pace might be a little gentler but the brooding narrative is utterly believable. His Jackson Lamb series features the ‘slow horses’ – MI5 agents who’ve messed up and been put out to graze in the backwoods of inactive service.

Herron’s crime isn’t spy-fi – there are no wacky gadgets to get Lamb’s crew out of a fix. The characters are vulnerable, disgruntled, and bored ... until there’s a crime and Lamb suspects the spooks. It’s a fine example of character-driven writing with attention to detail on Service procedural and detection legwork.

- For cosies, consider MC Beaton’s Agatha Raisin mysteries and Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple. Here, the amateur sleuth is surrounded by far less knowledgeable and somewhat hapless police officers.

- For hardboiled, think Chandler’s Philip Marlowe and Tim Weaver’s David Raker. Raker is a former journalist who, following the death of his wife, turns to investigating missing persons.

- Sara Paretsky and Sue Grafton offer two examples of gritty female PI protagonists in the form of V.I. Warshawski and Kinsey Millhone.

- One of my favourites is ‘accidental detective’ Myron Bolitar, a slightly softer-boiled sports agent with excellent martial arts skills and a compelling backup team.

- And let us not forget Precious Ramotswe, Alexander McCall Smith’s delicious founder of the No. 1 Ladies' Detective Agency. McCall Smith manages to keep things light without getting too cosy, and captivate without shocking. It’s gentle, penetrating crime fiction.

Telling your story through a point-of-view character who works outside law enforcement has its advantages: your protagonist can behave and move in ways that a detective can’t, at least not without risking their job.

On the other hand, your sleuth won’t have access to the wealth of contemporary resources available to the police.

And take care not to make your amateur’s successes depend on witless professionals. Certainly, every organization/service has its fools and bad apples, and crime fiction is the perfect tool with which to explore police and state corruption, but contemporary readers are unlikely to engage with a novel whose chief investigator is an oaf.

It shares the grit of hardboiled but is distinctive for its focus on the narratives of the transgressor (Eoin McNamee: Resurrection Man), the victim (Larsson: The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo), or both (Lippman: I’d Know You Anywhere).

The authors who do this subgenre best seem almost to be able to channel their characters’ psychosocial conflict, and dig deep into the predator–prey relationship.

And even when the detective is the protagonist, they’re less superhero than anti-hero, troubled by demons, working despite – rather than within – an establishment as troubled as them (James Ellroy: LA Confidential; Antonin Varenne: Bed of Nails).

Says Penzler in ‘Noir fiction is about losers, not private eyes’:

Regional variants – e.g. Tartan, Scandinavian, Emerald – that represent the landscape, culture, idiom, and social and political identity of their settings have emerged to international acclaim.

Consider also China Miéville's The City & The City. In this novel, two locations occupy the same physical space. At heart, it's a police procedural, but there's a speculative/fantasy take on the hardboiled tradition: the shiny surfaces of one city butt up against a grubbier alternate, yet residents of each are legally bound to 'unsee' each other. As such, Mieville incorporates a subtle commentary on state authoritarianism, surveillance and corruption into a murder investigation.

Genre syncretism can help your work stand out, but take care to recognize the conventions of each so that the core subgenre elements are all done well. No reader will thank you for promising a fusion of hardboiled and police procedural if both are half-baked. Good writing trumps everything.

I hope you find this useful and wish you sleuthing success on your crime-writing journey!

And there's that video I promised for those of you who'd prefer to watch or listen.

- ‘From cozy to caper: A guide to mystery genres’: Stephen D. Rogers, Writing World, 2002

- ‘Henning Mankell: I'm not afraid of dying’: Interview with John Preston, The Telegraph, 2011

- ‘How to write a crime novel’: Penguin Random House webinar with Dr Barbara Henderson, 2018

- ‘How to write a spy novel’: Kathrine Roid, 2011

- ‘In conversation: Ian Fleming and Raymond Chandler’: Transcript published in Five Dials, 1958

- ‘Michael Connelly interview: The modern Raymond Chandler on Bosch, The Long Goodbye, and LA's neighbourhoods’: The Independent, 2016

- ‘Modern hardboiled crime’: Matthew Lewin, The Guardian, 2009

- ‘Murder most cosy: Why mystery novels involving quilts and cats are big business’: Alison Flood, The Guardian, 2015

- ‘Noir fiction is about losers, not private eyes’: Otto Penzler, Huffington Post, 2010

- ‘Tartan noir: Crime, Scotland and genre in Ian Rankin’s Rebus novels’: Agnieszka Sienkiewicz-Charlish

- ‘The best locked-room mysteries: when impossible crimes aren’t’: Otto Penzler, Huffington Post, 2014

- ‘The Golden Age of detective fiction’: Reba White Williams

- The Locked-room Mysteries: Otto Penzler, Corvus, 2014

- ‘The origins of detective fiction’: RD Collins, Classic Crime Fiction, 2004

- ‘Writing spy fiction with an unputdownable plot’: Graeme Shimmin

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

BLOG ALERTS

TESTIMONIALS

Dare Rogers

'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'

Jeff Carson

'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'

J B Turner

'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'

Ayshe Gemedzhy

'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'

Salt Publishing

'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'

CATEGORIES

All

Around The World

Audio Books

Author Chat

Author Interviews

Author Platform

Author Resources

Blogging

Book Marketing

Books

Branding

Business Tips

Choosing An Editor

Client Talk

Conscious Language

Core Editorial Skills

Crime Writing

Design And Layout

Dialogue

Editing

Editorial Tips

Editorial Tools

Editors On The Blog

Erotica

Fiction

Fiction Editing

Freelancing

Free Stuff

Getting Noticed

Getting Work

Grammar Links

Guest Writers

Indexing

Indie Authors

Lean Writing

Line Craft

Link Of The Week

Macro Chat

Marketing Tips

Money Talk

Mood And Rhythm

More Macros And Add Ins

Networking

Online Courses

PDF Markup

Podcasting

POV

Proofreading

Proofreading Marks

Publishing

Punctuation

Q&A With Louise

Resources

Roundups

Self Editing

Self Publishing Authors

Sentence Editing

Showing And Telling

Software

Stamps

Starting Out

Story Craft

The Editing Podcast

Training

Types Of Editing

Using Word

Website Tips

Work Choices

Working Onscreen

Working Smart

Writer Resources

Writing

Writing Tips

Writing Tools

ARCHIVES

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

October 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

October 2016

September 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

March 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

November 2015

October 2015

September 2015

July 2015

June 2015

May 2015

March 2015

February 2015

January 2015

November 2014

October 2014

September 2014

August 2014

July 2014

June 2014

March 2014

January 2014

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

August 2013

June 2013

February 2013

January 2013

November 2012

October 2012

September 2012

August 2012

July 2012

June 2012

May 2012

April 2012

March 2012

February 2012

January 2012

December 2011

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed