|

Have proofreading symbols passed their use-by date? It’s a controversial question, but one that we definitely need to ponder. So, as an unconventional ‘celebration’ of 30 years in publishing, Melanie Thompson is setting out to answer this question – and she needs your help ...

Over to Melanie ...

A few months ago a colleague asked me whether (UK-based) clients want proofreaders to use British Standard proofreading symbols or whether they prefer mark-up using Acrobat tools on PDFs. ‘Good question,’ I replied. ‘I hope to be able to answer that later this year.’ That probably wasn’t the answer they were expecting. The widely different expectations of clients who ask for ‘proofreading’ has been niggling at the back of my mind for a couple of years. What's changed in three decades I have been a practising proofreader for 30 years, I’ve managed teams of editors and proofreaders, and I’ve been a tutor for newcomers to our industry. Yet I still learn something every time I proofread for a new client. It’s several years since I was last asked to use BS symbols for a ‘live’ project,* but I use them a lot on rough draft print-outs – because they’re so concise and … well, let’s face it, to some extent those symbols are like a secret language that only we ‘professionals’ know. I like to keep my hand in. But proofreading is now a global business activity, and ‘proofreading symbols’ differ around the world – which kind of defeats their original objective. And now so many of us work on Word files or PDFs (or slides, or banner ads, or websites or … ) and there are other ways of doing things. This all makes daily work for a freelance proofreader a bit more complicated (or interesting (if challenges float your boat). We might be working for a local business one day and an author in the opposite hemisphere the next. It’s rare, but not unheard of, to receive huge packets of page proofs through the mail and to have to rattle around in the desk drawer to find your long-lost favourite red pen. Usually, however, things tend to arrive by email or through an ftp site or a shared Dropbox folder. Digital workflows

The ‘digital workflow’ is something we’re now all part of, whether we realize it or not. But clients are at different stages in their adoption (or not) of the latest tools and techniques, and that leaves us proofreaders in an interesting position.

We need to be able to adapt our working practices to suit different clients; ideally, seamlessly. For that, we need to understand what the current processes are, and what clients are planning for the future. And that’s where I need your help. A new research project: proofreading2020 I’ve launched a research project, proofreading2020, to investigate proofreading now and where it might be heading.

The study begins with a survey, asking detailed questions about proofreading habits and preferences. Once the results are in, I’ll be conducting follow-up research for case studies and, early in 2019, publishing the results in book form.

You can find out more and complete the survey at proofreading2020. It's open now, and closes on 30 June 2018. Almost 200 proofreaders, project managers and publishers have already completed the survey. Several have contacted me to say it was really useful CPD, because it made them think about how they work and why they do things. So I hope you’ll be willing to set aside a tea-break to fill it in. It takes about 20 minutes to complete, but it’s easy to skip questions that aren’t relevant to you. There are only a handful of questions (at the beginning and end) that are compulsory (just the usual demographics and privacy permissions). Beyond that, the sections cover the following:

Your chance to join in!

Find out more and complete the survey at proofreading2020.

Don't forget, the closing date is 30 June 2018. * If a client does ask for BS symbols, I recommend downloading Louise’s free stamps for use on PDFs – they will save you a lot of time and help you deliver a neat and clear proof.

Melanie Thompson is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) and a CIEP tutor.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

0 Comments

Running an editing or proofreading business is a journey, not a moment in time. Some of us will be offered work that’s not ideal because of fee, content, client type, time frame, or for some other reason.

Some might tell us it’s a bum job, that we should run a mile. But is it? Should we? Would acceptance be a compromise or an opportunity?

The problem with ‘ideal’

Ideal is something to aim for but rarely what lands in our laps, especially in the start-up phase of a business.

The challenge of visibility Being discoverable is a challenge for many new starters. Ideal projects are out there, but the editor or proofreader isn’t yet visible enough in the relevant spaces. And even if they can be found, they might not yet have enough experience to instil the trust that leads to initial contact. Broadly, it’s easier to get in front of publishers because we know who and where they are. They’re used to being contacted by us, too, so we can go direct and cold. With non-publishers, it’s more difficult. Not every business, charity, school, indie author, or student wants an editor or understands the value we might bring to the table. Going direct and cold is a trickier proposition. The issue of trust It’s not just the mechanics of visibility. Emotion plays a part too, especially trust.

With publishers it’s easier to overcome the trust barrier. They know what they want, what we do, are used to working with us, speak our language, and are experienced in evaluating our competence.

Non-publisher clients are more of a challenge. They might not be familiar with the different levels of editing. Many will not have worked with a professional editor before. Some – for example fiction writers – might be anxious about exposing their writing to someone they don’t know. And for the inexperienced client, evaluating a good fit is more difficult. In the start-up phase of business ownership, editors and proofreaders with less experience might therefore find it easier to acquire work with publishers than with non-publishers. The choices on the business journey So visibility and trust issues mean that new entrants to the field might not have the same breadth of choice as the more mature business owner. It might mean deciding to accept work that isn’t ideal in the shorter term. We could describe this as a compromise, but might it in fact be an opportunity? Does the terminology matter? I believe the terminology does matter because a compromise has negative connotations.

Negatives leave us feeling dissatisfied, that we’ve been ripped off, that we’re not in control. We’re more likely to begrudge the choices we’ve made. Positives are empowering. We’re more likely to see the choices we’ve made as rational and informed. All of this might sound like a mindset game but there’s more to it than that. Decisions to accept work that isn’t ideal have measurable benefits. However, we need a longer-term approach, and that can be tough for the new starter who’s surrounded by colleagues who are booked up months in advance with the work that they want. If that sounds like you, think of your editing business like a garden. The editorial garden What you do this year is not separate from what will happen next year, or the year after, or five years down the road. All the choices you make on your business journey are connected.

The seeds you plant now will grow if you look after them. Give them a little additional feed and they might sprout this season ... if the weather holds and you’re lucky. However, you will not get a tree, not this year, I guarantee it. Trees come later.

If you don’t plant anything, however, nothing will spout, not now, not next year, not five years down the road. You will be treeless. Is planting the seeds a compromise? I don’t think so. It’s the opportunity to grow a tree. Should we begrudge all that work of watering and feeding for just a few green shoots in this season? Again, not to my mind. The effort we make now will bear fruit later. Our businesses are the same. A patch of my editorial garden I thought it might be helpful to share a story about my own business journey. It’s about how I accepted work that was way below my ideal price point, and did so with pleasure, because I believed I’d be able to leverage it later. See these books?

These are some of the books I was commissioned by publishers to proofread a few years ago. I proofread these books for about 13 quid an hour. These days, I aim to earn between £35 and £40 per hour. It doesn’t always work out that way, but I hit my mark in the last financial year when I averaged out my annual project earnings. A few years ago, my aim was around the £30 mark. Those books pictured above earned me less than half what I was aiming for. Did I compromise? Well, it depends how you look at it.

If I believe that each decision I make exists in the bubble of now, and that nothing affects anything else further down the road, then yes, I compromised. If I think that what I’m earning now is despite my decision to accept those proofreading projects, it was a massive compromise.

If, however, I decide that each decision I make can affect my choices down the road, that the walls around those individual decisions are permeable, it’s a different story. If I think that what I’m earning now is because of my decision to accept those proofreading projects, it’s a story of opportunity. Authors make decisions to work with editors based on a whole host of factors, but the first step is deciding to get in touch in the belief that the person they’ve found feels like a good fit. Back to trust To take one example, those of us who edit fiction for self-publishers are asking those authors to put their novels into the hands of complete strangers. Many of those authors have never worked with an independent editor. Some are anxious about the process of being edited. And for some, the editor’s might be only the second pair of eyes to read the text. It’s a big ask that takes courage. And that’s where the trust comes in. The editor who can instil trust quickly is more likely to compel authors to make the leap and hit the contact button. And what better way to instil trust than offer a portfolio of mainstream published books written by big-name authors? And that’s how I leveraged those half-my-ideal-fee books. They tell an anxious indie author that publishers of big-name books trusted me a few years ago. And that helps the author trust me now. Those proofreading projects – and the £13 ph fees that came with them – encourage authors to contact me now, and trust that my £35–£40 ph line/copyediting fee is a worthwhile investment. And I know it’s true because they’ve told me it's so. I didn’t compromise. I planted a seed. Now the tree has grown, and I’m able to harvest the fruit. I had to wait a few years but the decisions I made then affect the choices I have now. And that’s how an editing garden grows. Your choice I’m a great believer in leveraging for future opportunity. It’s not everyone’s bag. It doesn’t fit with every editor or proofreader’s business model. And that’s fine. I offer this not as THE way of thinking, but as one approach. It’s something that those at the beginning of their journey might like to consider if they are still building visibility, but struggling with the age-old rates debate! As independent business owners, we are free to accept or decline fees from price-setting clients as we see fit. We are also free to propose rates that meet our individual needs, regardless of what our colleagues are offering. If you’re offered work, can see the benefit of that work for your portfolio, but can’t stomach the price, decline. But if you wish to accept, even though others tell you the price is ‘too low’ or ‘unfair’, go for it. The hive mind of the international editorial community is there to offer support and to share its wealth of experience, but no one knows your business and your needs better than you! More resources

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Sentence length can affect tension. This post looks at how overwriting can mar the pace of a novel and frustrate a reader, and how less can sometimes be more.

Around eighty per cent of the books that end up in my editing studio are in the crime fiction genre.

One of the most common problems I encounter is overwriting. That’s not because the authors are poor writers. It’s because they’re nervous writers. It takes a lot of hard graft to put enough words on a page to make a book. Yet it takes an equal amount of courage to remove them ... or some of them. ‘What if the reader just doesn’t get it?’ ‘What if they’ve forgotten what I told them above?’ ‘What if I haven’t provided enough detail?’ ‘What if I just love both ways I’ve said that?’ These are the kinds of questions that result in anxious authors bulking up their prose. In a bid to help you trim the fat, I’m going to explore the following:

Trusting your reader The issue is sometimes one of trust – in the author’s own writing and in the reader’s ability to fill in the gaps. Some genres of fiction lend themselves well to more flowery prose that goes off at a tangent for a moment, a little narrative indulgence for the purpose of artistry or even titillation. Crime fiction, however, is all about the page turn. That doesn’t mean that the description isn’t rich, but there is an expectation of forward momentum. Avid readers of the genre love it for the thrill of the ride. Great characterization is key, of course. We want the protagonist to draw us in, the antagonist to pique our curiosity, and the supporting cast to deepen the picture, but ultimately we want to know whodunnit. And that means we want words that help us understand what’s happening, why, where, who’s doing it, whom it’s being done to, why it’s being done, and how it feels. And we only need to be told once. We might need a little clarifying nudge here and there but we’re capable of extracting a lot with less than you might think. Feisty fragments and snappy shorties If you’re trying to evoke tension in your reader, short sentences and fragments can be very effective. Look at the following examples and notice how the authors keep their narratives lean. Here’s an excerpt from Gone Bad by JB Turner:

Turner gives us just enough to set the scene – when, where, who and what – but no more. He trusts us to fill in the gaps.

He might have given a more detailed description of the forest – its sounds and smells. He might have delved deeper into Cain’s emotions, or helped us to picture the backpack by detailing the colour, make, number of pockets and zips, and where the ammo was being held. He could have told us, word for word, how Cain loaded the gun, how careful he was, which bullets he used. But he doesn’t. Turner leaves it to us to imagine the woods, to see in our mind’s eye the loading of the rifle, and to sense the cold hard determination of the shooter. And the backpack gets no more than a passing mention, because to do more would slow the pace and act as a distraction. And the result is just right – Goldilocks would approve. Now consider the choppy fragments in Jens Lapidus’s Life Deluxe:

Lapidus loves the colon more than any other author I’ve come across! It’s a hard piece of punctuation but it works because the characters we’re being introduced to lead hard lives. They’re always looking over their shoulders, thinking in short snaps, weighing up what’s in front of them ... and what might be behind.

Lapidus dares to trust us, dares not bore us. And because of, rather than despite, the short sentences and fragmented prose, reading the scene is an immersive experience for the reader. I recall a sense of taut fatigue as I read this book, like I was right there, ever watchful, on my guard. This author’s deliberate punctuation choices and choppy style mean the word count is reduced but the tension is heightened. He doesn’t pad his narrative with purple prose and stage direction. Like Turner, he trusts us to do the work. Damage by dilution Consider your own writing. Leave your draft alone for a few days. Then return to it and see what happens if you take a more reductive approach to a scene. It's all about balance at the end of the day. Not too much but not too little. Howard Mittelmark & Sandra Newman write:

I’m not suggesting you remove information the reader needs to know, but asking you whether there is material your reader doesn’t need to know, material that might bore them or hold them back.

Neither am I suggesting you avoid creating emotive scenes that are high on tension. Rather, might you build this tension with shorter, tighter sentences that demand your reader do some of the work? And I’m not suggesting you should limit every sentence in your book to five words – not at all. I’m suggesting that you might use this technique when you think it would work, when it would push your reader forward, when fewer words – the right words – would work as well or better than more, especially if you know you tend to overwrite. Letting go of what you love For some authors it’s not about trust, but about not wanting to let go. Perhaps you found two delicious ways to say the same thing and now you can’t bear to cut either. Or you constructed a stunning paragraph but it’s interrupting the conflict or the action. In The Magic of Fiction, veteran editor Beth Hill says:

Hill asks authors to grab ‘the liberty to cut words as freely as you added them’ and then to enrich what’s left.

It’s tricky for some beginner writers, I know, but repetition and interruption mean there are redundant words in your writing. And to make your novel sparkle, you need to let go of them because they’re not adding something new, they’re not in the right place, or they’re in the way. Take courage. Try it with and without. You might be surprised.

Cited works and further reading

If you'd like to access more tips and resources for self-publishers, visit the Self-publishers page on my website. Try these in particular:

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

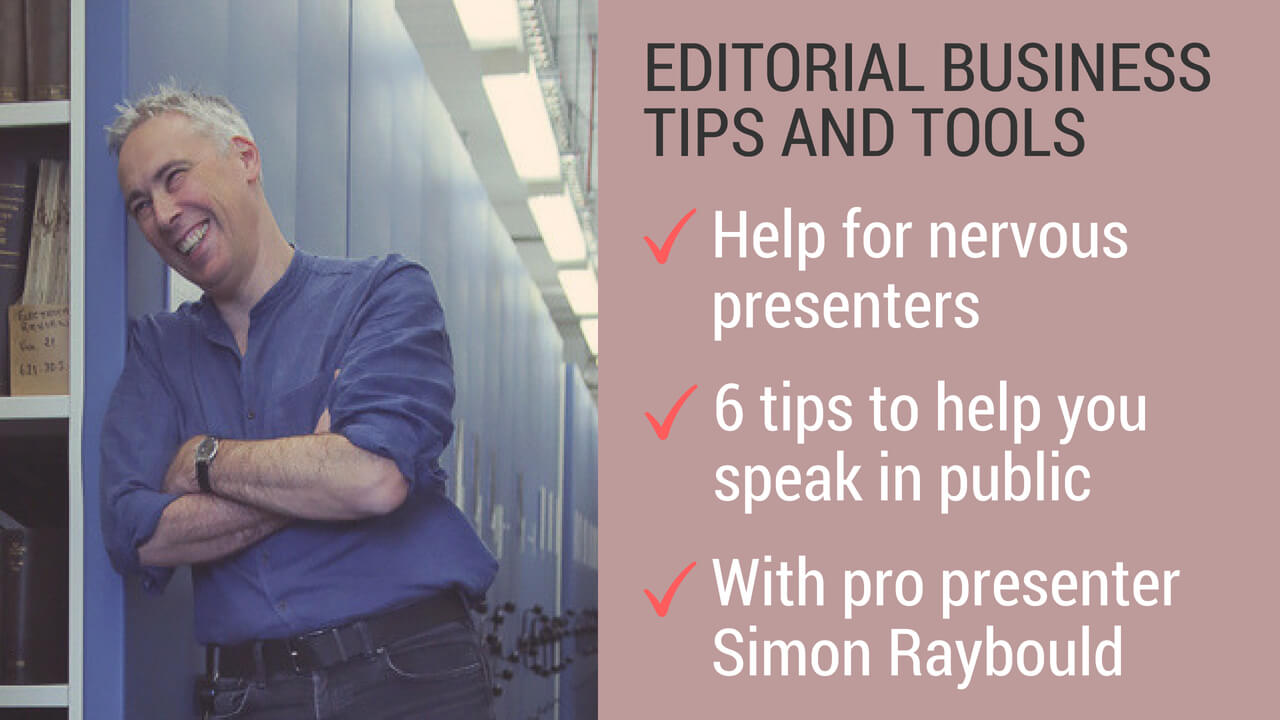

If speaking in public gives you the heebie-jeebies, professional presenter Simon Raybould has some advice that will improve your performance and calm your nerves.

Over to Simon …

You edit words for a living, right? It’s a cool job, I admit, and not one I could conceivably aspire to.

As someone once put it, 'Simon, being your proofreader must be like being Seán McGowan’s dentist.’ And yes, it’s true. She once sent me an email with the words ‘… first paragraph alone! Are you doing it on purpose? Are you trying to annoy me?’ But I think I have an even more cool option for you. Instead of editing words, why not edit minds? I’m not talking about some sci-fi concept – it’s what I do for a living. A good presentation will change someone’s mind ... and with it, their world. A good presentation is a form of telepathy – sending ideas from your mind to someone else’s. The upsides are awesome, but the downsides are pretty serious too:

But all is not lost – there are cures … or at least things that will help. Here are a few quick-to-master ideas and tools that will help you to present at conferences (or anywhere else) with confidence. Some are easy, some are harder, but all of them work.

1. The least popular tool – just doing it

Let’s start with the least popular option. When I ask people why they want to be confident, I often receive answers such as ‘If I were confident I’d be able to XYZ.’ And that’s great – they have a specific thing in mind. What’s not so great is that they seem to think that confidence alone will mean they don’t have to invest time in doing XYZ. I’m going to be blunt … you can’t shortcut your way to confidence. Don’t try to get confident before you do something. You can only get confident by doing that thing. Think about how you learned to ride a bike. Did you look at it, thinking, Cool! What an awesome bike. As soon as I’m a confident cyclist I’ll hop right on and go for rides in the hills? Nope. What you did was sit on it, fall off, get back on, fall off, get back on … and so on. Presenting is like that. Of course, with bikes you have stabilizers (and parents) holding you up. Stick with the analogy for a moment and figure out how you can make presentations in safer ways and places – stabilizers, as it were. How about making presentations under the following conditions:

I’m sure you get the idea. To mix my movement metaphors … don’t run before you can walk.

2. Know what success looks like

We all know what could go wrong, right? People might laugh at us; we could fall off the stage; cold sweat might drip down our backs or melt our mascara. And that’s the thing… we know what the bad things look like. But what about success? Not fainting on stage doesn’t count. Things like this count:

Define it. After all, if all you can identify is failure, that’s what you’ll concentrate on. But if you can define success, you stand a chance of concentrating on that instead. (Defining success also helps you to design your conference presentation more effectively. If you don’t know what you want to achieve, you’re more likely to omit core material.)

3. Sentence zero ... the breathing tool

When we’re scared, we breathe from the top of our lungs. Air comes out in a rush, making our voices sound thinner, breathier and – frankly – less authoritative. Hold that thought in your head for a moment and think about this: Lots of people tell me that once they get going in a presentation, things get better. So the important thing is to start well, right? Right. If you can control your breathing at the start, things are going to go better. Sentence zero is a handy tool for doing just that. Get the very first sentence of your presentation straight in your head. Be specific. For now, let’s pretend that Sentence One is ‘Hello, my name is Simon.’ Now think of a sentence that could go before it, finishing with the word ‘and’. For now, let’s pretend it’s 'Goodness, what a hideous lime green that back wall is, and …' We’ll call this Sentence Zero. Now, as you start your presentation, say Sentence Zero+Sentence One in one breath, but only use your voice for Sentence One. What that means is that your audience only hears Sentence One but you’ve already used the high-pressure, anxiety-sounding breath from the top of your lungs on the silent Sentence Zero.

4. Ditch the script

Writing is difficult. That’s why authors need you, right? So what on earth makes you think you can write a script for your presentation? If it was that easy, we’d all be writing massively successful West End and Broadway plays. Don’t try. Instead, define your structure.

Then, when you stand up to present, use the keywords as markers around which you improvise. Trust me, you’ll sound more natural and be much, much more interesting. Plus, you won’t spend time worrying about the massive confidence-drainer that is 'Did I get the wording absolutely right according to the script?' As an aside, the answer is no. No one does unless they’re RSC-grade actors. What you’ll lose in the occasional fumble you’ll more than gain in sounding more relaxed and natural. Plus, you won’t commit the ultimate presenter’s sin of using Latin words. It’s an over-simplification but we’re more likely write using the Latin-orientated words (‘commence’ rather than ‘start’) and speak using the Saxon versions (‘guts’ rather than ‘intestines’). Ditching the script means you don’t speak like a textbook.

5. Wasp-swatting: The power of the list

A while ago, my team and I sat down for a meeting. Pizza and wine might have been involved. One of the things we asked each other was what made us nervous. It turned out that about one-third of our conference nerves came not from the presentation but from the logistics that went with it.

Logisitical/trivial problems are like wasps. One seems manageable. A swarm’s a different matter. Each issue might be negligible on its own, but all of them together have a noticeable impact. Similarly, each on its own is easily dealt with, but taken together the problem loses its perspective. The solution is simple: a list. At least two weeks in advance of the conference, create a simple checklist – one line for every issue. For example, I don’t have a 'cables' tick box on my list; I have entry for the power cable, another for the VGA adaptor, and another for the HDMI adaptor, and so on. Before you go live, check the list. That way, when it’s time to perform, you can do so confident that you’ve not forgotten anything. It also frees up the parts of your brain you’d otherwise have wasted on trying to remember things. 6. Practice and rehearsal This is so fundamental it probably shouldn't come last. It also needs the fewest words. You will perform better if you go over your presentation and practise improvising using your keywords. Wrapping up There’s a lot more you can do to conquer your nerves – ideas range from breathing techniques to standing in certain positions – but these are good starting points. So go change the world and edit people’s heads!

Want to know more?

Simon's a presentations expert and productivity guru. If you want to get in touch beforehand, here's what you need:

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Today, I discuss the negative impact that just one word can have on narrative tension: Suddenly.

I’m not suggesting writers eradicate it, but rather use it judiciously and with intention.

I edit a lot of crime fiction written by beginner and emerging authors. I’m an avid reader of the genre too. Reading a genre isn’t enough to make anyone an expert in it, but it does afford the editor plenty of opportunities to see it written well, and to experience it as a punter ... to ask: Why do I like that? What is it about that scene that works so well? What’s hooking me here?

There’s one word that great crime writers put on the page with care – suddenly. However, many new or developing writers struggle to leave it out. Two reasons for overuse stand out:

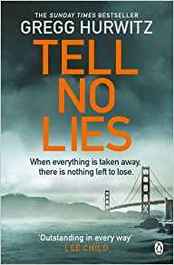

I’ve grabbed a handful of crime fiction from my own bookshelves, and taken examples from these books to show how suddenly-free writing can be more immediate and immersive. 1. Countering wordiness Some developing writers record every nod, every furrowed brow. All that mundane stuff happens in real life. And in the movies we get to see it played out onscreen. That doesn’t mean it all needs to go into a novel. Readers don’t behave like viewers. When I’m watching a film I expect to be spoon-fed to a degree – dialogue, facial expression, action, and a healthy dollop of incidental music to tell me who’s feeling what and why. The reason it works with film is because a chunk of that stuff happens simultaneously, and even I, impatient soul that I am, don’t get bored. When I’m reading a book, my brain works differently. I don’t want all that stage direction. Too much of it distracts me and that’s when I’m most likely to lose interest. When a new writer hasn’t learned the art of crafting the story so that there are just enough nudges to keep the narrative rich, but not so many that it becomes tedious, suddenly rears its head. Suddenly becomes an apology for overwriting – an exciting reward for sticking around. Only it doesn’t work. It’s just one more word on the page that the reader doesn’t need. Solution: Keep your crime writing lean Not every writer wants to strip their writing back to the bare bones but ask yourself whether you’ve introduced a sentence with Suddenly purely to reengage the reader. If so, tighten up the preceding narrative so that you don’t lose them in the first place. Less is sometimes more. Example Here’s a scene from Tell No Lies by Gregg Hurwitz, featuring the protagonist, Daniel Brasher (p. 393):

A less experienced writer might have been tempted to overwork the preceding description and the line conveying Daniel’s anxiety ... and that could have led to a Suddenly barging its way onto the starting blocks of the final sentence to drag the reader out of the protagonist’s head and back into the external action. It could have gone like this:

He was ushered through the door into a small, dank, grey windowless room with a stall terminating in a shield of ballistic glass that looked onto the mirror image of a facing stall. Only a steel table and two chairs furnished the room. A coaster-size speaking hole in the glass rendered jailhouse phones unnecessary.

He waited, counting the seconds, working to stay calm. Sweat dripped from his forehead, ran down his back and soaked his shirt. He massaged his temples to stave off the growing panic and raked a clammy hand through his damp hair. Just relax, he thought. You’re in control. Suddenly, a metallic boom announced the opening of an out-of-sight metal door ... Instead, Hurwitz has given us just enough to know that our protagonist is fretful. We hear the metallic boom in the same moment Daniel does. We imagine how it might make him jump. There are 58 words instead of 114. And the writing in the shorter, published example is tighter, the tension higher. The boom comes suddenly, but Hurwitz doesn’t tell us so. He doesn’t need to. 2. Redundancy – the verb’s already done the work Even those novice writers who’ve conquered their noisy narrative can still be tempted to nudge unnecessarily with suddenly. I see this most often in the following scene types:

Certainly, writers who use suddenly are doing so with good intention – to give the reader a now-nudge. However, in most cases it’s unnecessary to convey immediacy and adds nothing to the narrative. In the above examples, the immediacy is rendered perfectly with the verbs launched, dawned, lit up, exploded, trilled and slammed. By adding suddenly into the mix, the reader is pulled out of the story, as if the author has tapped them on the shoulder and whispered, ‘Hey, you, something big’s coming. Just so you know. Right then, as you were. Carry on reading.’ That’s an interruption – the opposite of what the writer intended. Now the reader’s no longer moving at the same pace as the character. They’re one step ahead rather than immersed in the moment. Solution: Test the sentence out loud Say it first with suddenly, then without. Ninety per cent of the time, the slimline version will work better. When that’s the case, hit the delete button.

Published suddenly-free examples Here are some published examples for comparison. None of the authors felt the need to nudge the reader into immediacy.

The Barclay example is particularly interesting. The narrative point of view in this chapter is that of the antagonist. From his perspective, the violence is almost mundane, which renders the scene all the more horrific for the reader. A now-nudge in this paragraph wouldn’t have been just superfluous; it would have countered the perversity of our tension being heightened through being forced to immerse ourselves in Cory’s psychosis. When suddenly works a treat Suddenly-free isn’t a rule. Don’t ban it from your novel! There are times when it works beautifully:

In this made-up example, the inclusion of suddenly subtly changes our perspective of Pip’s situation. There's a subtle immediacy to his discomfort has emerged only now, that in the seconds before he’d watched bu not felt threatened. And so it’s not that suddenly does or doesn’t work. Rather, it depends on the writer’s intention. Your turn ... how do you maintain tension with minimal interruption? Are there particular adverbs you use with caution? If you'd like to access more tips and resources for self-publishers, visit my resource centre. Try these in particular:

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

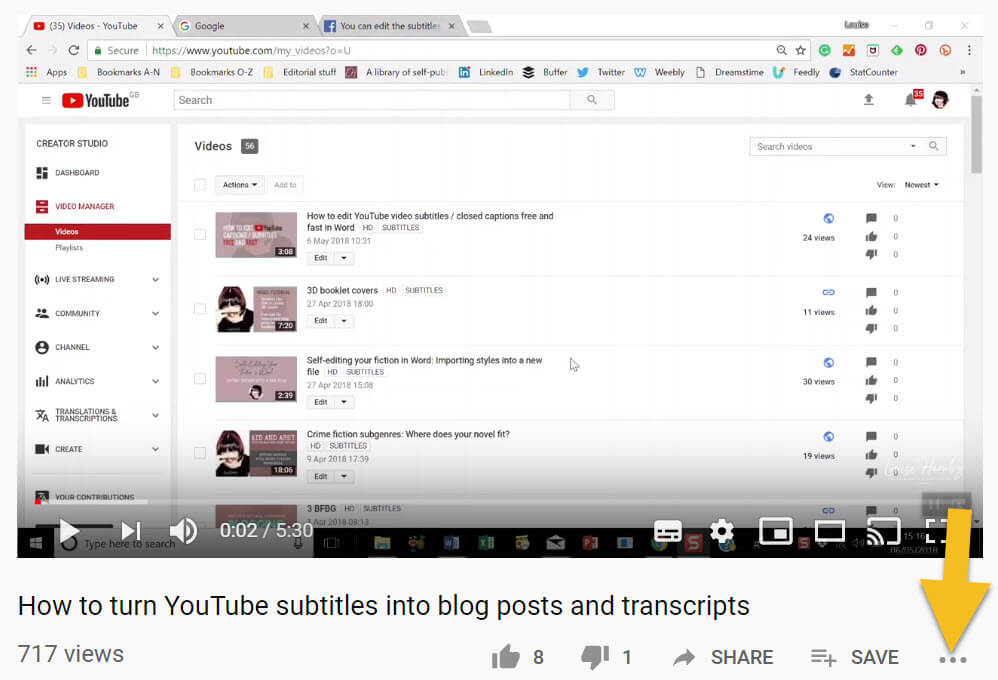

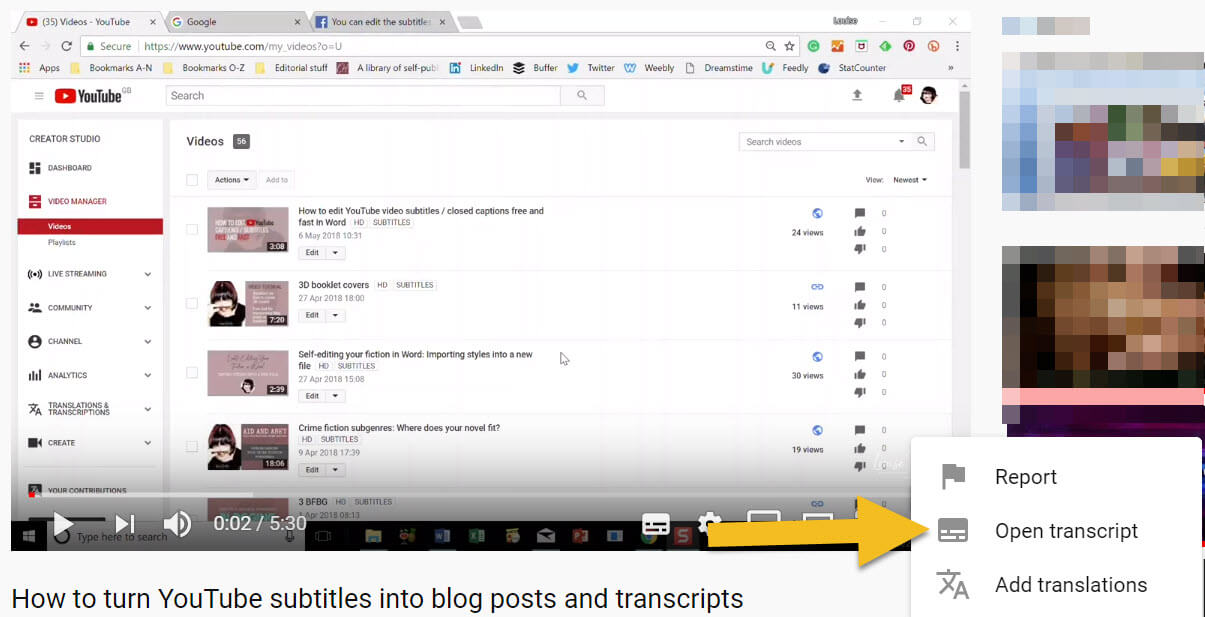

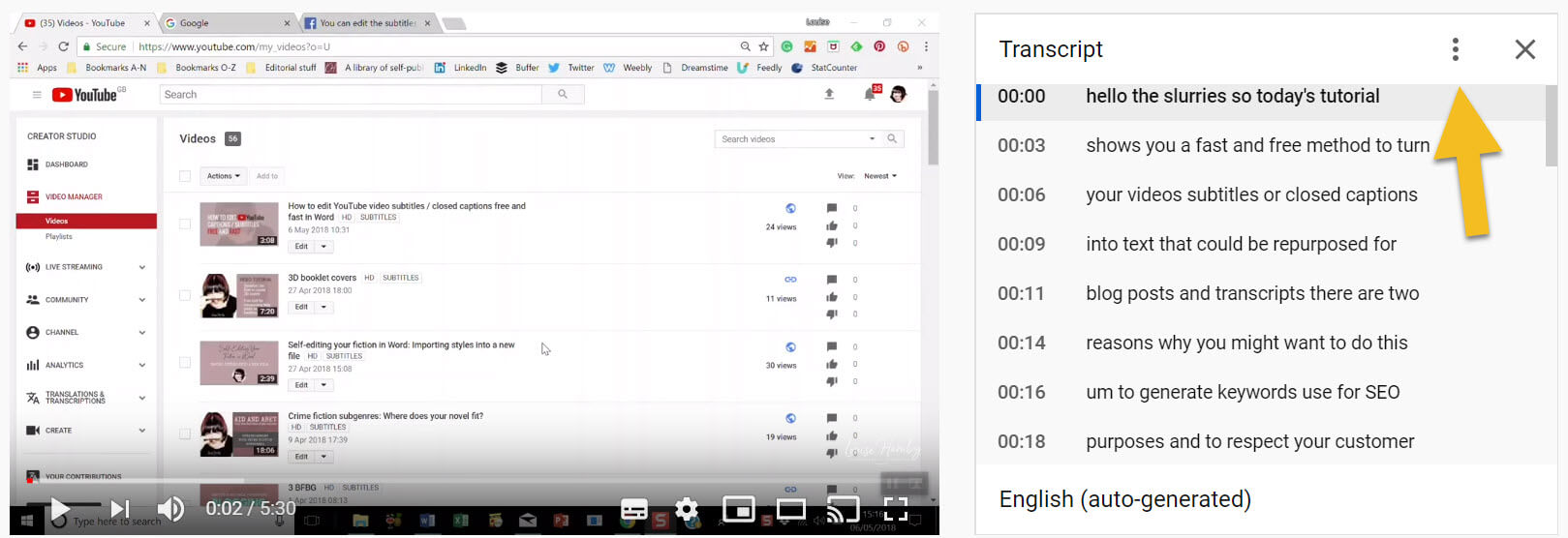

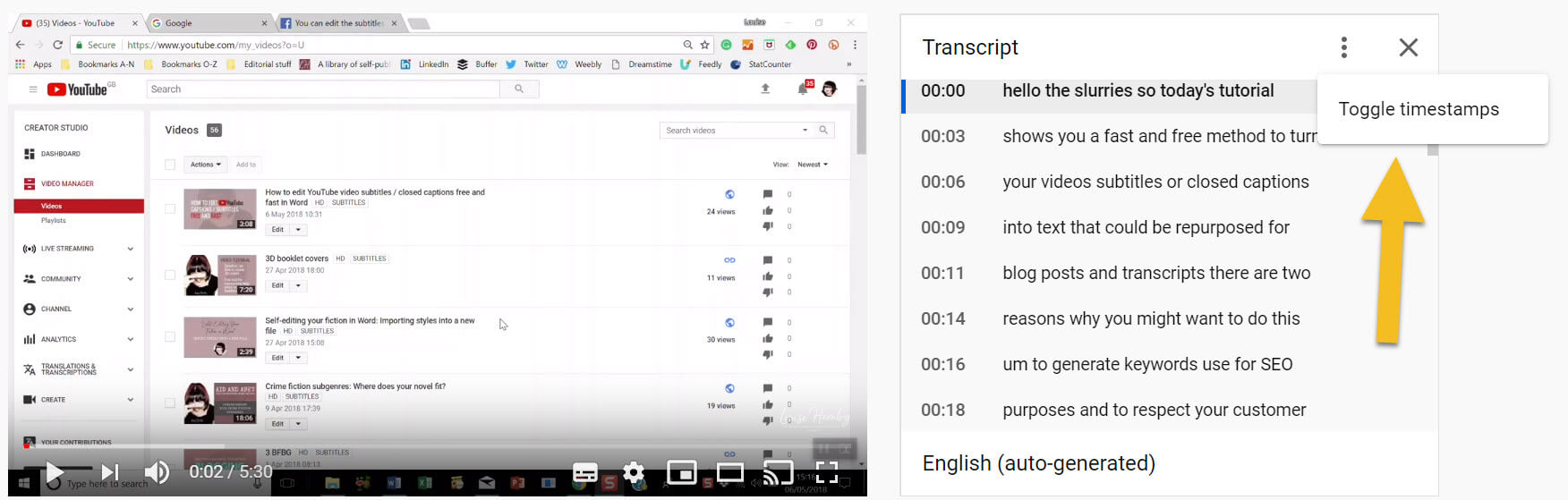

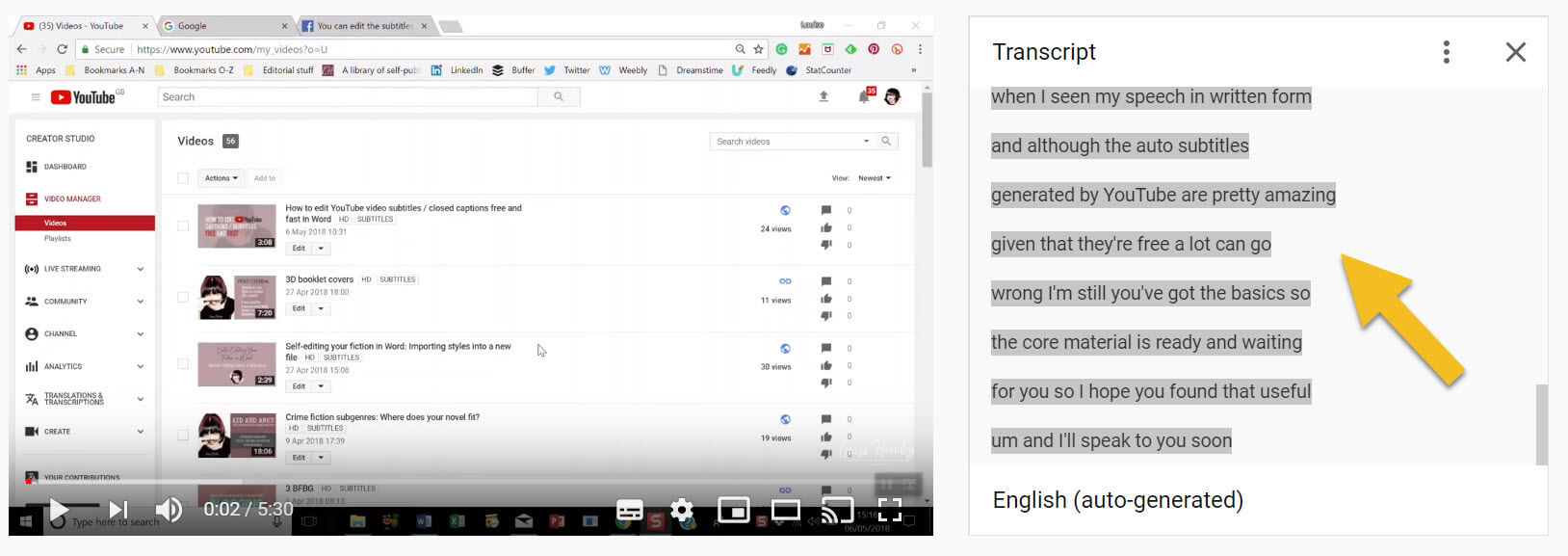

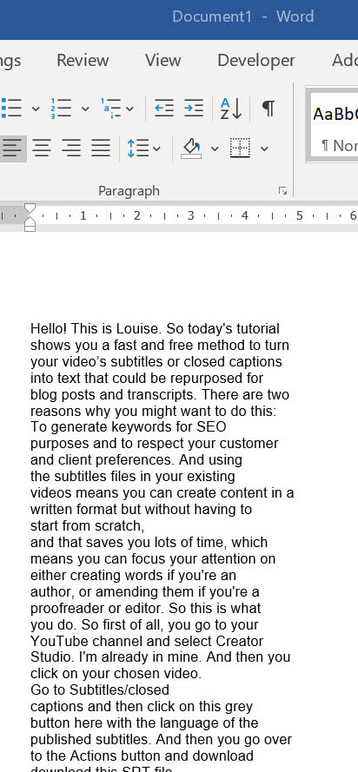

This tutorial shows you a fast and free method to turn your video’s subtitles/closed captions into text that can be repurposed for blog posts and DIY transcripts.

There are 2 reasons you might want to do this:

Using the subtitles files in your existing videos means you can create content in a written format without starting from scratch. That saves you precious time, allowing you to focus your attention on creating words (if you’re an author) and amending them (if you’re a proofreader or editor). Watch the video or use the written instructions below. Instructions

Your subtitles file now looks like this:

Edit your text to ensure the spelling and grammar are correct, and tweak the writing so that it meets your audience's expectations of written content.

If you're creating a blog post, introduce paragraphs, bullet points, headings and any supporting imagery. Generating keyword juice for SEO purposes Video is compelling. It allows our audience to see our faces and hear our voices. That intimacy can be compelling, and it’s a fast-track to building trust. That’s important for authors seeking to build a readership, and editors wanting to attract clients who need editing help. However, there are no keywords in a video. Yes, YouTube is a search engine in its own right, but it’s not the first point of search for every member of our audience. By repurposing video as blog content, we’re increasing our chances of being found in the likes of Google and Bing too. Being findable on multiple platforms makes sense in an online world that’s becoming noisier by the minute. Respecting customer/client preferences Not everyone wants to watch video, and even if they do, it’s not always the most convenient option. Imagine the following scenarios: Our reader’s broadband speed is slow A blog post will load faster than a video on those occasions that the internet seems to be creaking at the seams. If we’ve solved a reader’s problem in our videos, but they can’t play those videos, they could become frustrated and go elsewhere. If we’ve offered a written alternative, we’re more likely to keep them on our websites. Video is difficult to scan Written content is easy to scan and digest quickly. That makes it attractive to busy people. If our visitors can’t work out whether we’ve solved their problem without watching a video in its entirety, we might lose them. When we provide written content as well, we can quickly show them what’s on offer with headings and bullet points. Our readers can scan this information and decide whether to dig deeper. Blog posts can be printed Some people still like to print useful content so that they’re not reliant on digital means to access it. A video can’t be printed; a blog post can. Again, it’s about respecting what’s convenient for our readers, rather than focusing on our own preferences. Other options What I’ve offered here is a DIY solution for authors and editors who need to keep an eye on the purse strings when they're repurposing vlog content. It’s the method I use when I’m starting with a video rather than a blog post. Plus, I rather enjoy the process. However, it’s not everyone’s bag. If you have the budget, you can commission a professional transcriptionist or content repurposer. They’ll have the tools and expertise to create top-quality written content from video that fits your brand and voice. Summing up Editors and authors who are creating valuable content to make their books and editorial services visible can repurpose it in multiple ways. No one method trumps another – audio, video and words all have their place. However, our audiences will have different preferences. What’s convenient today might not work tomorrow. Repurposing content allows us to respect those preferences. The trick is to find shortcuts to that repurposing so that we’re not starting from scratch each time. This is one of them. Acknowledgement Thanks to JavaScript Nuggets for sharing this new and improved method of accessing transcript text. Much appreciated! Related resources

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

|

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed