|

Should editors offer free discovery calls? Our three-step discovery process will help you deliver the process effectively.

|

|

Online editing training course

|

Classification in UK

|

VAT must be charged to UK customers?

|

|

EXAMPLE 1

|

Digital service

|

Yes

|

|

EXAMPLE 2

|

Not a digital service

|

No

|

|

EXAMPLE 3

|

Probably not a digital service

|

Probably no

|

|

EXAMPLE 4

|

Possibly not a digital service

|

Possibly no

|

|

EXAMPLE 5

|

Nebulous

|

Nebulous

|

Your online course and the tax authority in other jurisdictions

Anyone offering online courses in a global market must know where their customer lives. And it’s the tax authority’s rules in the customer’s jurisdiction that determine whether we need to add a consumption tax to the price.

Which can be a monumental barrier for sole-trading editors and proofreaders. Why? because here's what we need to take responsibility for.

Our consumption tax responsibilities

Small-business owners selling digital products and services internationally must have a mechanism in place to:

- ensure that our customers provide the necessary jurisdiction data on our invoices

- allow our customers to exempt themselves from the tax where appropriate

- calculate the appropriate tax rate for every customer

- review that tax rate regularly (because they change!)

- collect the tax from the customer

- remit the collected tax to every single relevant tax authority. That's right. Every single one.

That list is enough to deter any small-business owner from sharing their knowledge and charging for it. Which is a crying shame because the editorial community is passionate about training and CPD.

And the fact is that most of us don’t have the time or skills to do this work – unless we decide we're not actually going to be editors and trainers anymore, but full-time accountants instead.

Nor can we afford to hire an expensive specialist tax accountant who will do this for us – unless we want the entire exercise to become unprofitable.

So what do we do?

The solution: Find a taxation-friendly training platform

What is a Merchant of Record?

A Merchant of Record is the legal entity that usually:

- calculates the appropriate rate of tax that needs to be added to a purchase of your course

- updates that rate of tax rate in your payment gateway when necessary

- collects that tax from your customer

- remits it to the tax authority in the appropriate jurisdiction.

When we choose a training platform that acts as the Merchant of Record, or includes a third-party integration that does the same, that leaves us free to get on with the business of editorial training rather than worrying about whether we’re tax compliant in every part of the world we’re selling to.

If the platform doesn't offer that, we're the Merchants of Record, and the buck's back with us.

What’s on offer?

Some training platforms are partial Merchants of Record. PayHip, for example, calculates, collects and remits VAT in the UK and Europe for me as a UK resident. However, I’m responsible for the tax compliance in all other jurisdictions ... Cue the worry.

Some training platforms include integrations that calculate the tax but don’t collect or remit it. That’s on us or our (expensive) specialist tax accountants. LearnWorlds is an example. The Quaderno app calculates what we owe to whom, but we have to do the rest ... Cue the worry.

Some training platforms act as full Merchants of Record, meaning they calculate, collect and remit all the tax for all jurisdictions. Teachable is an example ... And relax!

Where I host my editorial training courses

- It acts as a full Merchant of Record, meaning I can focus on course creation rather than worrying about tax compliance.

- The platform is super user-friendly for me and my students.

- Teachable has a gorgeous app (iOS and Android), which is fantastic for students who want mobile access. Download it from your usual app store.

- I can brand my content appropriately.

- Multiple editorial trainers use Teachable, which means students can access our schools via a single platform.

- I can now offer payment plans that allow my students to spread the cost.

- And there's a bundles option that lets me offer you access to multiple courses ... and with big discounts!

Note that at the time of writing, trainers wanting to offer PayPal as a payment gateway in Teachable must set their course prices in US dollars.

Teachable is right for me, but any editor or proofreader embarking on online course creation should do their own research. Most platforms offer a free trial so you can get a feel for the setup, functionality and branding options.

Summing up: What to consider

- Creating and delivering online courses for editors and proofreaders has never been easier thanks to the growing number of platforms with user-friendly interfaces and multimedia functionality.

- What’s not so easy is the tax-compliance element. Many of the providers haven’t yet woken up to the implications for small-business owners operating in a global marketplace with complex and ever-changing tax rules.

- If you’re planning to teach online, make sure you understand the differences in tax rules for courses with a live component and courses that are self-directed, not just in your own jurisdiction but elsewhere too. Also bear in mind that what constitutes live tutoring might be nebulous.

- And, finally, if you decide to head down the self-directed training route, and your preferred platform isn’t offering a full Merchant of Record service, think carefully about who’s going to do that work and how much it will cost.

Related resources

- Check out my courses, their payment plans, and discounted bundles.

- Visit my Skills and training resource page to access free guidance.

- Find out how to log in and access courses you've already purchased.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 96

- What's distinctive about editing crime fiction and thrillers

- What a good line editor needs to look out for

- What new entrants to the field need to study

- Marketing ideas

- Top tips for being a successful freelance editor/proofreader

- Do fiction editors use style guides?

Related resources

Join our Patreon community

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 90

- What the different types of editors do in media publishing

- The differences between subediting and copyediting

- Editorial timescales for subeditors

- Who controls the content

- When things go wrong - legal responsibilities and insurance

- Subediting lingo

- A subeditor’s typical day

- Transferring from copyediting to subediting - training and CPD

- Core resources for the budding subber

- How editing has changed over the years, especially for freelancers

Resources mentioned in the show

Join our Patreon community

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 88

- What a side hustle is and why it's popular

- Why there's resistance to the term 'side hustle' in the professional editorial community

- Whether an editorial business can be set up overnight

- The importance of skilling up and marketing

- The competition side hustlers have to deal with

- The different levels of editing

- How to find work

- Business-critical considerations

Join our Patreon community

- EditPod Tea Pot: Buy us a cuppa and help keep the podcast ad-free and independent.

- EditPod Tea Party: All of the above, plus you get exclusive access to quarterly live Q&As that help you keep your business on track.

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

What’s in this post …

- Why running a business means finding clients

- Working for others – being an employee

- Working on your business and in your business

- Setting up a business and marketing: The order of play

- Shifting from a no-time mindset to an all-the-time mindset

- Taking a strategic approach to marketing

Why running a business means finding clients

None of us can run a business if there’s no business to run. Editing and proofreading work is essential. Otherwise we’re nothing more than a fancy title on a business card.

If marketing isn’t a part of your business model, it’s time either to work for someone else or shift your mindset.

Working for others – being an employee

If you want to do your own thing, however, a commitment to business marketing must be part of the mix. That’s the difference between being self-employed and self-unemployed.

Working on your business and in your business

- The work they do

- And the work they do to get the work they do

There’s no way around this. The approach we use to find work will depend on who our target clients are. Think social media, content marketing, advertising, directory listings, professional membership, a visible website, letters, emails, networking, phone calls, and SEO. All or some of these will be in play.

If a no-time mindset is tripping you up, ask yourself whether you can imagine saying any of the following:

- I don’t have time to do editing.

- I don’t have time to send invoices.

- I don’t have time to check the spelling of a word in a dictionary.

Those statements sound daft, don’t they? Of course we’d make time for editing, invoicing and checking spelling! We’re professionals and we’re business owners – those things are essential.

Finding work is just as important. If we don’t, there’s no editing to do, no invoices to send, no spellings to check.

Since we’re employers (of ourselves), not employees, we must do our own marketing, right from the get-go, and continue to do it for as long as we’re in business.

Setting up a business and marketing: The order of play

If we spend 12 months training to be a professional editor but dedicate no time to our marketing strategy, all we’ll have at the end is a skillset that’s invisible to everyone but us.

I know how to make lasagne, change a tyre, and remove a thorn from a Labrador’s paw, but those skills in themselves don’t mean people are offering me work as a chef, a mechanic or a veterinary nurse. Why would they? No one but me, my husband, my kid and my dog know I can do that stuff. I’ve not promoted those skills or set up a business around them (nor do I plan to, just in case you’re wondering!).

If you’re serious about becoming a professional editor, so much so that you’ve invested your hard-earned cash in a high-quality training course, start working on your marketing strategy at the same time so that you don’t end up as a professional thumb-twiddler!

Shifting from a no-time mindset to an all-the-time mindset

Invoicing and tax returns are my least favourite aspects of running a business but I do them anyway. I have to. We all do.

Same thing with marketing. You don’t have to love marketing. You don’t even have to like it. Just do it anyway, all the time. Dedicate time in your business week to the task.

Every time you’re tempted to use that slot in your schedule to do something else, remind yourself that you don’t want to be self-unemployed, that you do want to earn a living from your editing business, and that when the client cupboard is bare it makes you feel miserable and stressed.

Taking a strategic approach to marketing

- ‘I'd better do a bit of marketing because I’ve got no work lined up next month’ is not a strategy. It’s an emergency.

- ‘Great! I just got some work for next month so I don’t have to do any marketing for a while’ is not a strategy. It’s a recipe for a future emergency.

- ‘I’ll accept that horrible low-paid job because it’s better than nothing’ is not a strategy. It’s a business model that puts others in control.

A long-term marketing strategy is planned, targeted, and implemented continuously. That’s what keeps the cupboard full of good-fit clients, and what gives us the power to decide a project’s not a good fit, the price isn’t right, or the scheduling’s too tight.

Summing up

You don’t have to do your marketing the way I do my marketing. The foundation of my strategy is content marketing, but that’s because I work exclusively with independent authors in a specialist genre, and want those authors to find me via Google.

Your marketing strategy should reflect the best method of being visible to your ideal clients. That might mean sending emails, making phones calls, engaging in a group or forum, or advertising in a particular space.

And even if you don’t like marketing, make it part of your business practice anyway. Place it alongside the other aspects of your business that you’re obliged to do but would rather not. Why? Because marketing can mean the difference between working and walking away. If you’ve already invested your energy and money in training, that’s a waste of your valuable skills. You deserve more than that.

And who knows? You might even enjoy promoting your business once you start reaping the fruits of your labour!

More marketing resources

- Blogging for Business Growth (course)

- Branding for Business Growth (course)

- Business Skills Collection (6 ebooks)

- Marketing resource library (books, booklets and blogs and podcasts)

- Marketing Toolbox for Editors (multimedia course)

- Marketing Your Editing and Proofreading Business (book)

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Listen to find out more about

- Brainstorming a list of possible business names

- Considering your target clients

- Identifying your core brand values

- Using a business name to tell the client what's on offer

- Checking the name is available

- Does the name reflect your brand identity?

- How findable and SEO-friendly is the name?

- Will the name stand the test of time?

Music credit

More business-tips resources

|

Check out these additional resources that will help you make good decisions for your editorial business.

|

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Perhaps the price or the time frame doesn’t work. Maybe the client has been in contact with an editor who’s a better fit in terms of skills and experience.

Still, there are steps we can take to maximize our chances of turning a request to quote into paying work.

Think of quoting as targeted marketing

Every request to quote is a marketing campaign with just one recipient. We have an advantage once we’ve been asked to quote – we’re probably competing with five or six colleagues, not five or six thousand.

Since the odds are so much better, it’s worth investing time in making the quote the best it can be. A couple of lines that include a price won’t cut the mustard – unless the client has specified that they want nothing more.

Acquire relevant information

Before we can reply, we need information – a word count, the type of editing required, the levels of editing that have already been completed, the client’s preferred time frame, and a sample.

If that information hasn’t been supplied, asking for it is legitimate. A professional editor can’t quote without it.

There are advantages too: it keeps the conversation going, demonstrates an understanding of the editorial business process, and creates a foundation for trust.

Frame with solutions

A potential client doesn’t want an essay – we do need to stay on point – but we can still frame our quotations in terms of solutions to problems.

- Solution-focused language demonstrates empathy.

- Being empathized with evokes positive emotions.

Once they’re in play, the conversation’s no longer about price; it’s about a relationship. If the client’s looking for the cheapest editor, yes, this tactic will fall flat. If they’re looking for a good fit, it will give us an edge.

Linking to or attaching useful resources builds empathy and trust.

Here’s what I included in a request to quote in addition to a price (the writer had included a sample):

- a booklet about the various levels of editing

- a booklet about punctuating dialogue

- a booklet about narrative viewpoint

- an article about filter words

Each of those resources complemented a short paragraph outlining problems I’d identified in the sample, and would fix if I were to secure the project:

- Viewpoint drops

- Telling rather than showing: too much exposition of doing been done that reduced immediacy

- Punctuation and standard paragraph layout problems

And the great thing is, I can use these resources over and over. Yes, it took time to create them but they’re evergreen.

Every author I send them to gets value from them. But every time I send them, there’s value for me too: a return on my initial investment in the form of an increased likelihood of securing the job.

A client who trusts

The writer thanked me profusely ‘for such a thoughtful reply’. I got the gig. And they agreed to wait 12 months and paid the deposit promptly.

I can’t prove that those resources nailed it for me, but those words – ‘such a thoughtful reply’ – tell me the client reacted emotionally to the empathy I’d shown.

Creating that kind of content is time-consuming but the job need be done only once. After that, the resource can be used in myriad ways: marketing, quoting, linking to in reports.

When the quote’s rejected

If we don’t get the gig, should we ask why? I don’t think so. It annoys me when I decline a service or product and am asked to give reasons for my decision. It’s my business, end of story.

Receiving feedback is useful for editors, of course, but we’re asking people who have chosen another editor to spend their valuable time engaging with us. Why should they? They have other priorities that don’t involve us and we need to respect that.

If a quote is rejected, move on and focus on improving your next quotation.

More resources on business growth and pricing

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

FIND OUT MORE

> Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

> Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

> Learn: Books and courses

> Discover: Resources for authors and editors

To be fit for working in any editing discipline, fiction or otherwise, training is the foundation. Even if you’ve been devouring your favourite genres for years, you need to understand publishing-industry standards.

This isn’t about snobbery. It’s about serving the client honestly and well, especially the self-publisher, who might not have enough mainstream publishing knowledge to assess whether you’re capable of amending in a way that respects industry conventions.

It’s about the reader too. Readers are canny, and often wedded to particular genres. They’re used to browsing in bookshops and bingeing on their favourite authors. They have their own standards and expectations.

One of our jobs as editorial professionals is to ensure we have the skills to push the book forward, make it the best it can be, so that it’s ready for those readers and meets their expectations.

And so if you want to proofread or edit for fiction publishers and independent authors, high-quality editorial training isn’t a luxury: it’s the baseline.

What kind of training you need will depend on what services you plan to offer.

I recommend the Publishing Training Centre and the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) for foundational copyediting and proofreading training. I’m based in the UK, and those are the two training suppliers I have experience of so I’m in a position to recommend them.

That doesn’t mean that other suppliers aren’t worth exploring. Rather, I don’t recommend what I haven’t tested. Keep an open mind. Check a range of suppliers and their course curricula. Then choose what suits your needs.

- Essential Proofreading: Editorial Skills One (Publishing Training Centre)

- Essential Copy-Editing: Editorial Skills Two (Publishing Training Centre)

- Proofreading 1–4 (CIEP)

- Copy-editing 1–4 (CIEP)

- See also this list of professional editorial societies; they’ll be able to advise you if you live outside the UK

If you want more information about how the PTC and CIEP courses compare, talk to the organizations’ training directors.

2. Decide which fiction editing services you want to offer

Some beginner self-publishers don’t understand the differences between the different levels of editing, which means they might ask for something that’s not in their best interests (e.g. a quick proofread even though the book hasn’t been critiqued, structurally edited, line- and copyedited).

It’s essential that the professional fiction editor is able to communicate which levels of editing they provide, and recommend what’s appropriate for the author.

That doesn’t mean the author will take the advice, but the editor must be able to articulate her recommendations so that independent authors can make informed decisions.

The next step is to gain skills and confidence with fiction editing and proofreading work. As with any type of editing, the kinds of things the editor will be amending, querying and checking will depend on whether the work is structural, sentence-based or pre-publication quality control.

When deciding what specialist fiction editing courses to invest in, bear in mind the following:

- Even if you have experience of developmental editing non-fiction, this skill will unlikely transition smoothly to story-level fiction editing without specialist training.

- Even if you’re an experienced sentence-level fiction editor, this skill will not make you fit to offer structural editing or critiquing without specialist training.

Courses and reading

Explore the following to assess whether they will fill the gaps in your knowledge. Check the curricula carefully to ensure that the modules focus on the types of fiction editing you wish to offer and provide you with the depth required to push you forward.

- Switching to Fiction (Louise Harnby; course: webinar and book)

- Introduction to Fiction Editing (CIEP; course)

- Developmental Editing: Fiction Theory (Sophie Playle, Liminal Pages; course)

- Developmental Editing: In Practice (Sophie Playle, Liminal Pages; course)

- Editing Fiction (Publishing Training Centre; introductory e-learning module)

- Write to be Published (Nicola Morgan; book)

- The Magic of Fiction (Beth Hill; book)

This isn’t a definitive list but it’ll set you on the right track.

Fiction editing requires a particular mindset for several reasons:

Style and voice

We’re not only respecting the author, but the POV character(s) too. The fiction editor who doesn’t respect the voices in a novel is at risk of butchery.

Being able to immerse oneself in the world the writer’s built is essential so that we can get under the skin of the writing. If we don’t feel it, we can’t edit it elegantly and sensitively.

Intimacy

Non-fiction is born from the author’s knowledge. Fiction is born from the author’s heart and soul.

If that sounds a little cheesy, I’ll not apologize. Many of the writers with whom I work are anxious about working with an editor because they’ve put their own life, love and fear into the world they’ve built.

A good fiction editor needs to respect the intimacy of being trusted with a novel. If that doesn’t sound like your bag, this probably isn’t for you.

Unreliable rules

At a fiction roundtable hosted by the Norfolk group of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading, guest Sian Evans – an experienced playwright and screenwriter – talked about how punctuation in screenplays is as much about ‘the breaths’ the actor is being directed to take as about sentence clarity.

These ‘breaths’ exist in prose. They help the reader make sense of a sentence ... not just grammatically, but emotionally. And so the addition or removal of just one comma for the sake of pedantry can make a sentence ‘correct’, or standard, but shift tone and tension dramatically.

The fiction editor needs to be able to move beyond prescriptivism and read the scene for its emotionality, so that the author’s intention is intact but the reader can move fluidly through the world on the page and relish it.

All of which is a rather long-winded way of saying that if you want to get fiction editing work, and keep on getting it, you’ll need to embrace rule-breaking with artistry!

Fiction work requires us to respect both readability and style. The two can sometimes clash so gentle diplomacy and a kind hand will need to be in your toolbox.

5. Read fiction

If you don’t love reading fiction, don’t edit it.

And if you don’t love reading a particular genre, don’t edit it.

Editing the type of fiction you love to read is a joy, and an advantage. If you read a lot of romance fiction, you’ll already be aware of some of the narrative conventions that readers expect and enjoy.

I started reading crime fiction, mysteries and thrillers before I’d hit my teens. I turned 51 in March and my passion for those genres hasn’t waned. That stuff makes up over eighty per cent of my work schedule too. Here’s the thing though – my pleasure-reading has supported my business.

I get to see first-hand how different authors handle plot, how they build and release tension, how they play with punctuation, idiomatic phrasing, and sentence length such that the reader experiences emotion, immediacy and immersion. And that helps me edit responsively.

Honestly, reading fiction is training for editing fiction. In itself, it’s not enough. But professional training isn’t enough either. Love it and learn it.

If you want to understand the problems facing the self-publishing author community, listen and learn.

Join the Alliance of Independent Authors. Even lurking in the forum will give you important insights into what self-publishers struggle with an how you might help.

Take advantage of online webinars aimed at beginner writers. Penguin Random House offers a suite of free online resources. Experienced writers and instructors take you on whistle-stop tours of setting, dialogue, characterization, point of view, crime fiction writing, children's books and a whole lot more.

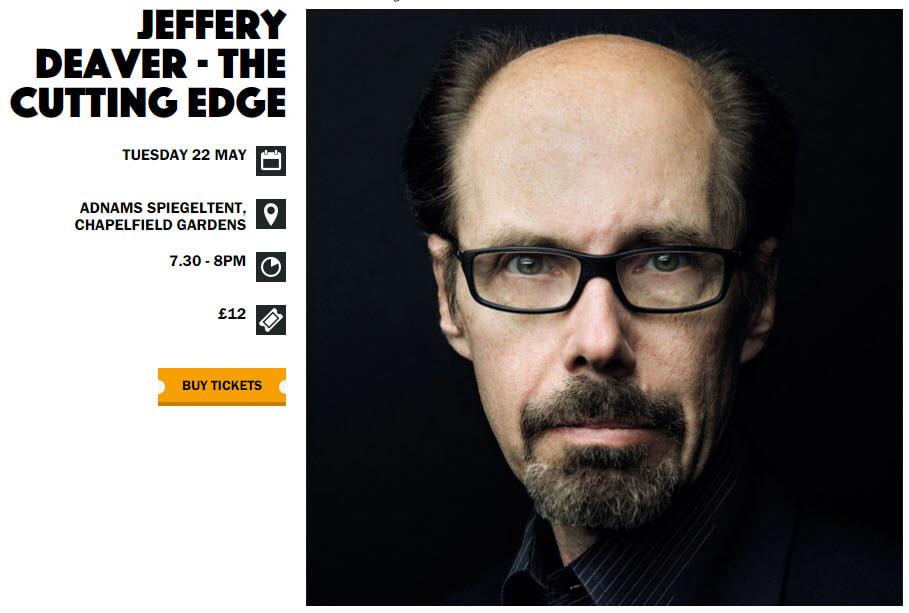

Listen to published novelists’ stories. My local Waterstones hosts regular author readings/signings. I’ve seen Garth Nix, Jonathan Pinnock and Alison Moore speak. In April 2018, Harry Brett is chairing a session on how to write crime with Julia Heaberlin and Sophie Hannah.

In May, fellow editor Sophie Playle and I are attending 'Why Writing Matters', an event hosted by the Writers' Centre Norwich in association with the Norwich & Norfolk Festival. And Jeffery Deaver's coming to town too. Ticket booked!

These workshops cost from nothing to £12. That's a tiny investment for any fiction editor wanting to better themselves.

The best way to get publisher eyes on your editing skills is to go direct. Experienced fiction editors are sometimes contacted direct but sitting around waiting to be offered work never got the independent business owner very far and never will.

Experienced ... but not in fiction

If you’re an experienced editor or proofreader who already has publisher clients but they’re in a different discipline (e.g. social sciences, humanities) you’ll likely have built some strong relationships with in-house editors.

Publishing is a small world – in-house staff move presses and meet each other at publishing events. It might well be that one of your contacts knows someone who works in fiction and, more importantly, will be happy to vouch for your skills.

With specialist fiction training, you’ll be able to leverage that referral to the max. So, if you have a good relationship with an in-house academic editor, tell them you’d like to explore fiction editing and ask them if they’d be prepared to share a name and email and give you a recommendation.

Newbie

If you’re a new entrant to the field, it’s unlikely that a cold call to HarperCollins or Penguin will be fruitful. The larger presses tend to hire experienced editors with a track record of hitting the ground running.

There are two options:

- Target smaller, independent fiction presses. Ask if they’d consider adding you to their freelance list. Be clear about the training you’ve done and your genre preferences. The fees might not be great, but I recommend you look at this as a paying marketing and business-development opportunity. You’ll be able to leverage the experience, the testimonials and the portfolio entries later.

- If the small press responds by saying that they aren’t in a position to hire external editorial work, ask if you might do a one-off gratis proofread/edit for them as a way of gaining experience and supporting their independent publishing programme – mutual business backscratching. Again, you can leverage this experience when targeting paying fiction clients (publishers and indie authors).

There’s no excuse for any twenty-first-century professional editor to be invisible. There’s no one way to visibility – take a multipronged approach.

Directories

If you’re a member of a national editorial society, and they have a directory, advertise in it as a specialist fiction editor/proofreader.

If you’re not a member, become one. It won’t be free, but running a business has costs attached to it. If we want to succeed, we need to be seen. That doesn’t land on our plates; we must invest.

If your society doesn’t have an online directory, lobby for one to be set up and promoted. I’d go as far as to argue that a professional editorial society that isn’t prioritizing the visibility of its members isn’t doing its job properly.

- The Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) IS doing its job properly. I rank highly in Google for certain keyword phrases, but it’s not always my website that shows up – sometimes it’s my CIEP directory entry. It thrills me to know that my membership sub is providing me with networking, friendship, training opps, and visibility in the search engines.

If you don’t qualify for inclusion, make doing what’s necessary a key goal in your business plan.

- Reedsy – despite what you might have heard – does NOT set low rates that encourage a ‘race to the bottom’. Editorial professionals set their own rates and Reedsy takes a cut of the fee. I receive several requests a month to quote for fiction copyediting or proofreading via Reedsy and have worked with some wonderful authors. Entry in Reedsy’s database is free but you must have a certain level of experience to be invited.

Again, if you don’t qualify for inclusion, make doing what’s necessary a key goal in your business plan.

Create content for indie fiction authors

Any self-publishing fiction writer looking for editorial assistance is more likely to think you’re wowser if you help them before they’ve asked for it.

Create resources that offer your potential clients value and you’ll stand out. It makes your website about them rather than you. And it demonstrates your knowledge and experience.

Doing this might require you to do a lot of research, but what a great way to learn. Don’t think of it as cutting into your personal time but as professional development that makes you a better editor.

And think about it like this: Who would you rather buy shoes from? The shop where the sales assistant tells you all about her, or the shop where the sales assistant helps you find shoes that fit? It's no different for authors choosing editors.

I have an several pages dedicated to resources for fiction authors. I’m not alone. These fiction editors have resource hubs too: Beth Hill, Sophie Playle, Lisa Poisso, Kia Thomas and Katherine Trail. There are others but I’m already over the 2,000-word mark!

Shout your fiction specialism from your website’s rooftop. Why would a fiction writer hire someone who doesn’t specialize in fiction when there are so many people dedicated to it?

Here are some additional articles that you might find useful if you're considering moving into the field of fiction.

- The different levels of editing: Proofreading and beyond

- How do mainstream publishers produce books?

- Should a writer hire a freelance editor before submitting to an agent?

- What's a sample edit? Who does it help? And is it free?

- Fiction editing resources for editors

- Resource library for editors

Good luck with your fiction editing journey!

|

Here's a free webinar where you can review this guidance and other various aspects of fiction editing.

|

And if you're thinking about transitioning from non-fiction but are unsure what else you need to know, take a look at my course, Switching to Fiction.

|

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

It’s important to remember that not everyone’s lowest-paying clients are publishers. If yours are, it might be that you need to switch clients not types of client. Here’s my wise friend and fellow editor Liz Jones:

‘It’s often said that publishers don’t pay as well as non-publishers. In my experience, this isn’t necessarily true. There isn’t much difference in the mid-range, and fewer of my non-publishers feature at the low end, but my highest payers in 2016 were still publishers.’ Crunching the Numbers

Just think of these examples as glimpses rather than universal statements of how the market is!

Joe Word-King is a professional proofreader specializing in the social sciences. He works exclusively for publishers. In the past 12 months he’s been commissioned by 5 publishers to proofread 32 books by 32 authors.

Joe’s working day

Joe starts at 9 a.m. and finishes at 4.30 p.m. He takes an hour for lunch and 15-minute breaks every 90 minutes to give his eyes a rest.

This means he has a total of 6 hours per day available for proofreading. During the breaks he does stuff like checking his emails, grabbing cups of tea and something to eat, and taking a little fresh air.

How he acquired those publisher clients

One found him in the Society for Editors and Proofreaders’ Directory of Editorial Services. Four added him to their freelance list after he emailed them and asked if he could take their proofreading test (which he passed).

How the work offers come in

The publishers do the author-acquisition work. The book production managers from those presses email him to ask if he’s free to take on a project of A pages, B words, with a budget of C hours and a total fee of £D. Joe decides whether he will accept or decline the work.

Alicia Sentence-Queen is a professional copyeditor. She works exclusively for independent fiction authors. In the past 12 months she’s been directly commissioned by 19 authors to copyedit 19 books.

Alicia’s working day

Alicia starts at 9 a.m. and finishes at 4.30 p.m. She takes an hour for lunch and 15-minute breaks every 90 minutes to give her eyes a break.

She also spends an average of 75 minutes per day writing blog articles and sharing her content online so that her website is visible in the search engines.

This means she has a total of 4 hours and 45 minutes available per day for copyediting. During the breaks she does stuff like checking her emails and social media accounts, grabbing cups of tea and something to eat, and taking a little fresh air.

How she acquired those self-publisher clients

Fourteen came directly from Google, three from the CIEP’s Directory of Editorial Services, and two from Reedsy.

How the work offers come in

Alicia does the author-acquisition work. She makes herself visible online so that her clients can find her. They then get in touch directly. A process of evaluation, sampling and quoting begins. Alicia offers a price for the project and waits to see whether the author will accept or decline.

Most of the enquiries that Alicia receives don’t turn into paid work – perhaps the author doesn’t like the price, the time frame doesn’t work, or Alicia doesn’t feel she’s the right fit for the job. For that reason, Alicia needs to attract enough people for whom the price, the time frame and the fit will work.

Alicia’s heart is in copyediting and she figures that if she had a bunch of publisher clients doing all the author-acquisition work she wouldn’t have to devote 75 minutes per day to making herself visible.

She earns a minimum of £35 per hour. Given that she spends 6 hours and 15 minutes each week marketing, that time costs her £218.75. That works out at nearly a grand a month!

She and Joe are good mates so she gets in touch with him and tells him that she’s thinking about working for publishers. They chat about fees – Joe says he earns an average of £23 per hour, which is two thirds of what she’s getting from her indie authors. Given that Joe proofreads for academic presses, Alicia does a little more digging.

She talks to a few fiction specialists. The fees for trade publishers seem to be lower still, such that she could end up averaging around £18 an hour, half of what she’s earning now.

- If she started working only for publishers, she’d have 6 hours a day available for editing, meaning she’d earn £540 (£18 x 6 x 5) per week.

- If she carries on working with indie authors she can earn £831.25 per week (£35 x 4.75 x 5).

What could Alicia do?

If Alicia loathes marketing and can meet her weekly needs with £540, she could take the hit and switch to working with publishers, who will do all her author-acquisition work for her and let her concentrate on doing what she loves best. Yes, she’ll earn less but she’ll be happier.

If Alicia loathes marketing but needs to earn at least £750 a week to meet her needs, the switch won’t work. She can’t not do the marketing because the reason why she’s able to attract the clients who are prepared to pay her £35/hr fee is because she’s visible, and being visible means doing marketing.

If Alicia’s determined to switch solely to publishers, she’ll have to make up a shortfall of £210. That means reducing her monthly spend or increasing the hours she spends on copyediting.

She’ll need to decide whether either option would add a level of stress into her life that exceeds her hatred of marketing. If it does, she’d be better off maintaining the status quo!

Joe has a change of heart too!

After chatting with Alicia, Joe feels a little strung out. Thirty-five quid an hour? He’d love to earn that. Joe’s not averse to putting in the marketing work, not if he can earn the money that Alicia’s on, but it’s not going to happen overnight – Alicia told him that it took a few years for her marketing strategy to kick in so that’s she’s never without work.

At the moment, Joe doesn’t have to do anything to find his authors; the publishers do all the grind for him. Sure, he had to get those publisher clients, and he put in a lot of effort – he contacted 70+ presses initially, most of whom weren’t taking on new indie proofreaders.

Nevertheless, having now secured a strong publisher base, he sits back and lets the work come to him. There’s a cost to this, of course – someone else is finding the authors and so they get to control the price. His only control over the rate is his right to accept or decline the work.

What could Joe do?

If Joe can introduce efficiencies into the proofreading process he’ll be able to improve his hourly rate. If he’s already as efficient as he can be, he’ll need get his marketing hat on now and start building his visibility.

Over time, he’ll be able to slide out his lower-paying publishers, confident that he’ll attract enough good-fit clients to provide him with the same income stability that the publishers currently afford him.

If he needs to maintain his current earnings, he’ll have to do the additional marketing work outside of his normal office hours. In the longer term, as the visibility strategy kicks in, he’ll be able to mimic Alicia’s model and build this marketing activity into his business day.

Joe needs to decide whether the impact on his work/life balance is something he’s prepared for. He needs to set the pressure of the additional work against the anxiety born from the publisher fees, and decide whether the change is the right move for him.

On the surface, it might seem like the Alicias of this world have a better deal than the Joes. But there’s more to running a business than just numbers. We have to take into account not just what we need to earn but also what we have to do for what we earn.

If you’re happy to be an editor and a marketer, you’ll be able to reap the benefits from wearing those two hats purposefully. If your heart lies in editing only, you have some choices:

- Do the promotion work anyway, even though you’d rather not.

- Suck up the (sometimes) lower fees and enjoy the stability and security of knowing that someone else is doing the stuff you’d rather not.

- Negotiate with your current publishers and see if you can increase your fees. Even a marginal increase might make the rate more palatable.

- Search for new publisher clients who pay higher rates. Again, even a small increase might make you feel happier,

I worked exclusively for publishers for a good few years and at the time it suited my life very well. I had a toddler to look after and preschool trumped business promotion. Now I have a teenager and marketing trumps Minecraft!

Plus, I happen to love marketing my editorial business so it's not a stress point for me. But that might not be the same for you.

Furthermore, the editorial market isn’t binary. Joe and Alicia might look nothing like you. You might sit somewhere in between. You might earn more than them or less than them, and have a ton of demands in your life that J&A will never experience. There’s no one size fits all.

Just don’t forget that if you’re not finding your own clients, but your schedule is full, someone else is doing the job for you.

There’s a cost to that, and it’s fair that there should be.

Further reading

- Bang for a limited buck: Liz Jones, Eat Sleep Edit Repeat

- How to make proofreading for publishers profitable: Digital efficiencies

- Increasing editing income – raising fees and declining lower-paid work

- The highs and lows of editorial fees (or how not to trip up during rate talk)

- The rates debate: Looking at the value beyond the fee

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Thanks so much for allowing this to be a open forum/platform for beginners like me to ask questions!

I am a 23-year-old law graduate who currently works as a commissioning editor for a online science publishing company. However, even though this has been a 'foot in the door' type of position, my heart is really set on going into trade publishing and becoming a freelance editor.

Not only that, my position here as a commissioning editor isn't what it actually says on the tin – it's more on the commissioning side of things rather than editing. In fact, I do no editing whatsoever, in my opinion! So I feel like I'm not gaining the necessary skills I need for the industry.

I was thinking that obtaining a well-recognized qualification would help get me noticed, as my ultimate goal is to become a freelance editor – but without gaining the necessary experience in my current role, and without the qualifications, I do feel like I'm at loss here. I've also applied for a number of roles but been unsuccessful owing to my lack of experience. Freelance agencies have also rejected my application for the same reasons – not having enough experience.

Furthermore, there's also no way of acquiring clients where I work. Please help!

Thanks so much for your question, Pritti!

I accept that your current role won’t give you the practical experience you require because you’re in a commissioning rather than production role. However, I don’t think that needs to stand in your way of embarking on training that will prepare you for developmental editing, line editing, copyediting or proofreading in a freelance capacity.

No training provider will turn you away because you don’t already have the experience! The UK’s Society for Editors and Proofreaders, for example, offers a suite of online training courses designed for novices and experienced professionals alike.

I wonder whether because you’re working in-house you’ve got yourself into a mindset of thinking like an employee. If want to work as an independent editor, you need to start thinking like an employer (of yourself). That means sorting out everything for your business from your training to marketing to administration.

Getting qualifications

My first piece of advice is therefore to sort out the qualifications issue. I’ve covered this in several previous Q&As, so take a look at the articles and the list of national editorial societies below. You haven’t told me where you live but there are several distance-learning options available (in Canada, the US and the UK, for example).

- Are free online proofreading and editing training courses reliable?

- Q&A with Louise: Can a teacher get work as a proofreader, even with no publishing experience?

- Q&A with Louise: Which online proofreading and copyediting courses do you recommend?

- Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading

- The Publishing Training Centre

- Why should you bother with professional proofreading training?

- Worldwide list of editorial societies

Once you’ve acquired the practical skills, you’ll be in a position to begin the journey of acquiring work. Again, though, I think you need to shift into the mindset of a business owner.

Getting work

Freelance agencies are certainly one option, but that’s a narrow approach to take given the many others worthy of exploration. Here are some additional ideas:

- Develop your marketing strategy. You can begin this now and add to it as you learn. Check out my books and the marketing archive here on the blog

- Join a professional editorial society and advertise in its directory

- Create a business website that shows how you can solve your target clients’ problems and what services you offer

- Create professional social media accounts (e.g. a Facebook Page and LinkedIn and Twitter profiles) that enable you to engage purposefully with fellow editors and potential clients

- Contact publishers and ask to be added to their freelance banks. I don’t mean two or three – I mean for you to get serious about it! (See SOS Marketing Strategy)

Your subject specialism

You told me that you’d like to work in the trade publishing sector. The term ‘trade’ refers to the publishing of materials for a general audience.

If you want to be found by, for example, independent thriller writers, you’re going to need to be visible, and that may take time while you build your portfolio and your SEO.

If you want to do freelance work for trade publishers (for example, Pan Macmillan or Little, Brown) you’ll might well struggle until you have more experience under your belt (unless you get lucky). I think this is something you should set your sights on further down the road.

In the meantime, focus your efforts on building your freelance business – marketing yourself and practising your post-qualification craft.

I always recommend that new entrants to the field focus attention on the market where they’re most likely to stand out. Specialize in what you know first; diversify later.

You have a law degree. I don’t. That’s why I’d never copyedit for a law student or an academic submitting an article to a legal journal. And while I have proofread law books for academic publishers, those clients never asked me to copyedit.

Your law degree means you speak a language and have a knowledge base that I don’t (and many other experienced editors don’t). You can use that to differentiate yourself.

When I began my editorial business journey, I had professional training, a politics degree and experience of working in-house for a social science publisher. I didn’t spend valuable time trying to get my business off the ground by asking Gollancz if I could proofread their SF Masterworks series (much as I would have loved to do that!).

Instead, I went and knocked on the door of social science publishers and spent several years honing my craft with politics, sociology, philosophy, economics and media studies books.

Over time, new opportunities arose as I became more visible and my marketing efforts began to bear fruit. But it did take time, and while that happened I concentrated on where my strengths lay so that I could gain experience. I believe that you need to do the same.

I think you should focus on the following client groups to begin with:

- Publishers with law lists

- Social science and humanities publishers (think related disciplines such as criminology, international law, public policy and administration, and philosophy and ethics)

- Legal students and scholars

- Independent authors of commercial non-fiction (this is your where you'll get your related trade experience that you can sell on later to trade publishers)

Some academic publishers also have trade divisions/imprints and so the academic work can deliver trade opportunities to the independent editor.

Summing up

I hope that helps you get your thoughts in order, Pritti. If you take things one step at a time, I’m confident you can get to a point where you’re immersed in the trade sector. But I’d recommend building up to it by playing to your market strengths.

Good luck!

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Does sexually explicit written material deserve to be edited? What is it exactly, and what is it not? And if you want to edit it, how do you make yourself visible to its authors?

Here’s my take. And it is only my take. Some of my colleagues won’t touch the stuff with a bargepole. And those of us who will? Well, we all have our individual boundaries.

What is pornography? And what is it not?

If only there were a universally accepted definition of pornography. There isn’t, alas. What you consider porn may not be what I consider porn. Or one of us might think a written work is more erotic than pornographic. Others might not even bother making a distinction.

And that’s the first thing any editor needs to recognize. The term ‘pornography’ is loaded with subjectivism and preconceptions, many of them heteronormative, so what you’re expecting and what actually ends up in your editing studio could be two very different things.

‘Pornography is notoriously difficult to define, and overburdened with assumptions concerning – at the very least – gender, sexuality, power, globalization, desire, affect, and labour,’ say Rebecca Sullivan and Alan McKee.

Oxford offers the following broad definition: ‘Printed or visual material containing the explicit description or display of sexual organs or activity, intended to stimulate sexual excitement.’

And broad it is. Too broad, in my opinion, because it doesn’t exclude materials with descriptions or displays of non-consenting performers and minors, which are illegal.

What we can say is that definitions are contested – in society, in the courts, and in academic literature.

That makes it difficult for the editor who’s asked, ‘Do you copyedit pornography?’ because even if you think you don’t, others might think you do because they have different opinions on what constitutes porn.

So what do we do? I think custom guidelines are the answer, particularly if you decide to publicize the fact that you’re happy to edit sexually explicit material. Before we discuss these, let’s consider erotica.

If there is a difference, it’s unlikely that the lines of distinction so clearly drawn in your own head will be shared by everyone else you consult on the matter.

Echoing Sullivan and McKee, Leon F Seltzer notes the degree to which ‘the criteria used for distinguishing between the erotic and pornographic [are] … steeped in personal moral, aesthetic, and religious values’.

And he goes on to say that the erotic ‘doesn’t appeal exclusively to our senses or carnal appetites. It also engages our aesthetic sense.’

Tracy Cooper-Posey’s distinction draws specifically on novel-craft: erotica isn’t ‘only about sex, unlike its gutter-cousin, pornography. At its purest, the new erotic novel is a brilliantly-written story with super-nova sex that compliments the caliber of the writing, and is fundamental to the plot and characters. In other words, if you remove the sex, the story can’t be told.’

And so it may be that if you, the editor, decide a manuscript’s sexually explicit content contains enough celebration of the human form and is written to a high enough standard, or has a good enough plot, then it’s erotica. If not, it’s porn.

It seems to me that getting bogged down in the definitions will get us nowhere fast. The terminology is as tangled as that used to describe editorial services (well, maybe not that bad!).

If the author’s struggling to write well, but is trying to create erotica, who am I to say it’s porn? And if it’s just sex that aims for nothing but titillation, but it’s written beautifully, artfully, does that mean it’s no longer porn?

If your decision is down to the art-versus-smut argument, one thing’s for sure: you’re going to need to see a sample. And if you want to work on only certain types of material, you’ll do well to create some guidelines.

Guidelines don’t just help you and the writer decide whether you’re a good fit. They’re also a great way of demonstrating your engagement with the subject and your willingness to have a conversation with a nervous or embarrassed author.

What should you include? There’s no one way of going about this; include whatever’s important to you and what you want the author to know. Here are just a few ideas:

- Your personal definitions of pornography, erotica, and romantic fiction (or other genres and subgenres), with an acknowledgement that the author’s might differ.

- An explanation of what kinds of materials don’t constitute pornography (e.g. law-enforcement agencies, social services agencies and criminologists don’t use the term ‘child pornography’ but rather ‘child-abuse materials’).

- A summary of the laws in your jurisdiction regarding sexually explicit material.

- The genres and subgenres you’re comfortable editing, and those you’d rather not.

- Your approach to depictions of adult sexual violence and to what degree you’d feel comfortable editing this.

- How you identify (re sexuality, gender, faith, race, ethnicity, etc.) and to what degree you’d feel confident editing material in which the characters identify differently.

- Clarification that you’re comfortable with profanity.

‘Even filth needs editing,’ said my colleague Louise Bolotin when she wrote about the issue on my blog back in 2012, and I agree.

The porn and erotica writers for whom I’ve worked are as committed to their writing as any crime fiction, thriller or literary fiction author.

A client recently told me, ‘I love my writing and with your help I hope it can lead to something else. If we don’t dream, then we don’t create. I’m proud of my stories but this is a whole new world for me, and like anybody who writes, there’s insecurity.’

What was I dealing with? Not plot, no. Seltzer’s and Cooper-Posey’s definitions chimed here. But my client needed a lot of help with punctuation to make the narrative readable. He’d omitted all speech marks, so the dialogue was invisible. There were repetition and syntax problems. But the writing was strong – imaginative, funny, clever, sexy – and in this book at least, I think he had a great turn of phrase (almost poetic at times). The pace was good, the language potent, and the sex appropriately disgraceful. All in all, I think he did an excellent job!

Even so, prior to editing, the book wasn’t publishable because it didn’t conform to recognizable standards of spelling, punctuation and grammar. The reader would have struggled to enjoy the story because they’d have been pulled out of it with every missing full point and speech mark.

And that’s my job (and yours) – to help the author help the reader. So, yes, I think pornography and erotica are absolutely worthy of being edited.

We know there’s a market for pornography and erotica. There are readers with an appetite for these genres, and writers ready to feed it. Those writers need editors to make those stories as good as they can be.

If you’re comfortable working on adult material, then you’d do well to make this clear because there seems to be a dearth of professional editors advertising the fact.

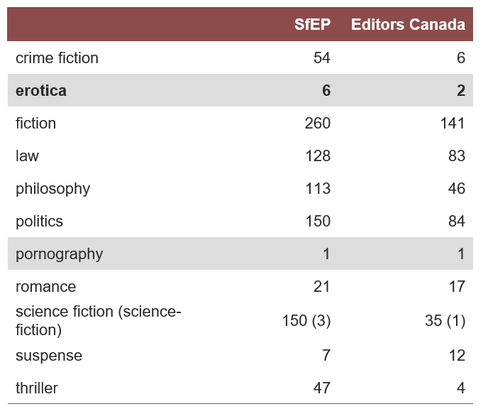

Here are some numbers generated by searching the UK’s Society for Editors and Proofreaders’ Directory of Editorial Services and the Editors Canada Online Directory of Editors using the following key words:

If pornography and erotica are genres you want to edit or proofread, approach the issue as you would any other subject specialism.

The political science professor will be drawn to editors and proofreaders who make it explicit that they welcome this type of work, have experience of editing the subject matter, and provide resources and guidance that demonstrates that expertise.

Pornography and erotica authors are no different. And so:

- If you have some relevant works in your existing portfolio, make sure they’re part of your visible portfolio (website, directory entries for example).

- Look at the description of your website in the search engines. The following is clearly visible in mine: Proofreading and editing genres include crime, science fiction, mystery, thriller, suspense, fantasy, horror, supernatural, speculative fiction, and erotica and pornography. Make sure your website description is complete and contains keywords that you want to be found for.

- Create resources and articles that help solve authors’ problems. For example, some authors might struggle with biology, others with repetition, yet others with clarity. Some might benefit from advice on how to approach an editor without fear or embarrassment. Are there useful writing resources about pornography and erotica writing that you might curate? All this content tells the author that you’re engaged and willing to discuss the subject.

- Publishing those resources on your website will make you more visible in the search engines, especially when they’re talked about, recommended, shared and linked to.

Some editors are keen to take on the work but anxious that it might reflect badly on them. Does being public about your willingness to edit pornography and erotica damage your reputation?

I don’t believe so. Pornography and erotica are recognized genres. As long as we present our willingness to edit them with the same professionalism as we’d approach politics or philosophy, science fiction or romance, I see no problem.

I and several of my editor friends are open about the fact that we work on adult material and none of us has suffered problems acquiring work.

I think that’s down to the fact that we’re all committed to marketing our editorial businesses, and focusing on the value we can bring to the table.

That’s what clients concentrate on, not the things that are of no interest to them. The thriller writer cares that I work on thrillers, not that I also copyedit erotica and historical fiction.

Editors aren’t the only Nervous Nellies. Some of the writers who’ve contacted me about editing porn and erotica are anxious too. The emails usually start with something on the lines of ‘I feel a little embarrassed about this but …’ or ‘I hope you don’t mind me asking but …’

Again, guidelines and resources can help to reassure an author before they send the email.

Summing up

If you’re happy to edit porn and erotica, go for it. If you aren't, that's fine too. As independent business owners we can choose what material we want to work on and what we don’t.

Wanting to edit a particular genre isn’t enough. Make sure your willingness to edit porn and erotica is visible – on your website and in the editorial directories you advertise in. If you don’t say it, you won’t be heard.

Further reading

- Leon F Seltzer, ‘What Distinguishes Erotica from Pornography?’, Psychology Today.

- Louise Bolotin, ‘Editing Adult Material’, The Parlour.

- Rebecca Sullivan and Alan McKee’s Pornography is an accessible and highly readable exploration of the subject through an academic lens.

- Tracy Cooper-Posey, ‘An End to Euphemisms: Is Erotica Right for You?’, Tracy Cooper-Posey | Stories Rule.

Watch a video instead ...

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

She asks:

‘At the moment, I do a lot of academic work, which I love and would like to continue; I just want to secure it privately rather than through third-party sites. In addition, I would like to move away from website copy, blog posts and more generalised proofreading, and start working with publishers on longer and more interesting projects. However, I don’t know where to start, what’s required, or how to approach them. Many thanks for any guidance you can provide!’

Thanks for your question, Abigail!

So, something else you mentioned in your email to me is that you’re undergoing professional training. I was really pleased to hear this because I think it’s an essential element in the mainstream publishing market. I’m going to focus on the following:

- Why targeting publishers is such a good step

- A quick note on earnings and work stream

- Training for academic publishers – what you need to know

- Where academic publishers search

- Why going direct is still your best bet

- Don’t put all your eggs in one basket

- Taking academic publishers’ tests

- Asking for testimonials and building a portfolio

Why targeting publishers is such a good step

Publishers are still the preferred client group for many editorial freelancers. There are several reasons for this:

- Publishers do all the project-acquisition work for us, which means we can sit back and allow the work to come to us (if we have enough publishers in our pockets).

- They understand what we do – we don’t have to nail our brand identity in a way that’s becoming increasingly critical if we want to be visible in the search engines! No proofreading or copyediting course will teach you how to build a compelling brand, and doing that is an art in itself! Getting a publisher’s attention requires a strategy that’s skills- and experience-focused.

- The definitions of proofreading, copyediting and developmental editing are homogeneous. You won’t be asked to proofread an academic textbook but expected to sort out the structure. The terminology in the rest of the world is rather more tangled (see the Untangling Proofreading booklet below).

A quick note on earnings and work stream

There’s a lot of talk in the online international editorial community about publishers and low fees. The situation is not straightforward.

There is no universal fee for copyediting or proofreading. I rarely work for publishers these days, but when I did I was offered proofreading fees from academic presses that worked out as low as £10 per hour and as high as £40 per hour.

It depends on the complexity of the project, the press, the brief, the length, the number of authors, and a ton of other things. After you’ve done a few projects for a publisher, you’ll start to get a sense of how things work and what you can expect to earn on average.

Some publishers will offer you a fee of £X per hour, and a guideline for the number of hours they expect the project to be completed in. Some will offer a flat fee for the job. Some of my colleagues (like Liz Jones: see her excellent post in Further reading, below) have successfully negotiated fees when they encountered scope creep.

With some presses, I found that I could counter what seemed initially to be a less favourable fee by being as efficient as possible.

You’ll also speed up as you become more familiar with a press – their house style, the format of their books, and their preferred professional style manuals and reference systems.

Regardless of their fee structure, they do all the project-acquisition work for you, which means you can sit back and focus on the proofreading and editing rather than worrying that your Google Search rankings aren’t as high as you’d like!

In order to ensure you’re fit for purpose with publishers, ask them which style guides and reference systems they prefer, and take time to familiarize yourself with these manuals. Most presses will provide you with a summary of their preferences.

Your training course should draw attention to the importance of following a brief. Publishers are usually rigid when it comes to scope, and going beyond the brief without querying first could have detrimental consequences.

For example, if you’re training to proofread, you’ll need to practise when to change, when to query and when to leave well enough alone – no in-house editor will thank you for recasting sentences to improve the flow in a proofread.

That’s because: it’s expensive to make extensive changes on page proofs; the pagination could be affected; cross-references might be impacted; and the index could be damaged if it’s being created simultaneously.

Also check that the training course you’re doing is recognized by the UK publishing industry. You won’t go wrong with the following organizations, though they’re by no means the only ones to consider:

Certainly, if you want to proofread for publishers, you’ll need to be familiar with the industry-recognized proof-correction markup language (BS 5261C: 2005). Even if a publisher asks you to proofread on PDF, you might be required (or find it efficient) to use digital versions of these marks.

Where academic publishers search

Some publishers do search for editors and proofreaders. The SfEP’s Directory of Editorial Services is one port of call. Some also attend the SfEP’s annual conference and the London Book Fair, so those two events are worthy networking opportunities to put yourself on the radar of academic presses.

Recently, I was contacted by a publisher via Reedsy. It’s the first time I’ve received a request to quote from a press via this platform, and it was for a fiction title, so I’m not convinced that this would necessarily be a primary channel for you if you want to acquire academic work, but I’m mentioning it just as food for thought.

Why going direct is still your best bet

My top tip for getting in front of publishers is to contact them direct, by email, phone or letter. The reason why many don’t search online for editorial freelancers is simply because they don’t need to.

Build a list of UK academic publishers, then find out the name of the person in charge of hiring – it’s probably someone in the production department – and get in touch with them.

You already have lots of experience, and you’ll have a top-notch training course under your belt. I recommend customizing your CV and cover letter/email for each press so that your portfolio of projects sells you as a perfect fit.

Read Philip Stirups’ article for more top tips (see Further reading).

Don’t put all your eggs in one basket

I recommend you build a bank of around ten publishers. If you stick to one or two you could end up in deep water further down the road. If one of those clients were to merge with another, you might fall off the freelance list during the transition. If your other client were to go bust, you’d be scuppered.

Having a larger bank of publishers means you have a safety net.

It’s likely your publisher client base will grow exponentially; each time you acquire a new client you’ll be more likely to impress another. It’s a small world, and many of the in-house staff know each other. That will work in your favour.

Taking academic publishers’ tests

Some publishers will ask you to take a test. There are two articles in the Further reading section that offer excellent overviews of how to approach these: ‘The Business of Editing: Editing Tests’ by Rich Adin, and ‘Test Taking Tips For Editors’ by Cassie Armstrong.

Asking for testimonials and building a portfolio

Are you able to ask current academic clients for testimonials? If so, do so – however embarrassing you find it! This kind of social proof won’t on its own get you work, but it’s one way of demonstrating that you’re capable of fulfilling a client’s brief.

I mentioned your portfolio above. If you’ve been in business for five years, chances are you have an amazing project portfolio. Make sure your CV, LinkedIn profile and website reflect your body of completed works. Publishers love to see experience!

I hope that brings you a little clarity, Abigail. Good luck with building your new client base!

Further reading

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

She says: ‘I have zero experience in publishing. However, I have a first-class degree in Education Studies and enjoy reading and grammar. I've been reading your blog recently and have thought of qualifying as a proofreader but appreciate how competitive it is. What is the likelihood of me obtaining work based on my background?’

Many thanks for your question, Amanda!

So, the short answer is, there’s a strong likelihood if you get your marketing head on.

Because, essentially, this is a marketing issue.

Here’s my current favourite mantra:

We have two jobs: the work we do, and the work we do to get the work we do.

In your email to me you talked in terms of ‘qualifying’ so you’re clearly prepared to embark on professional training – a wise decision. It tells me you’re prepared to make yourself fit for practice – the work we do.

Now let’s look at what you could do to get that work.

1st-stage marketing (pre-qualification)

- Start working on your editorial website

- Create an editorial Facebook page

- Create an editorial Twitter account

- Create an editorial LinkedIn page

- Join the Society for Editors and Proofreaders and introduce yourself in the forums there

- Think about your target clients

These are the basics, but they’re enough to give you a solid set of standard online profiles that represent you and your proofreading business, and that will enable you to connect with like-minded professionals – old hands and new.

In reality, your potential client base is rather wide, but I believe that in the start-up phase, when you’re building a proofreading business, it makes sense to target publishers. That’s because:

- They already have their hands in the air – the want your services. You don’t have to persuade a publisher that hiring a proofreader is a good idea!

- Their definitions of proofreading match what you’ll be taught when you train. Outside the publishing world, things become more tangled. Many indie authors call proofreading what a publisher would call copyediting.

- They’re easy to locate and contact. You’ll need to find out the name of the person in charge of the freelance pool – it’ll probably be someone in the production department.

2nd-stage marketing (post-qualification)

So why would a publisher be interested in you, Amanda? Here are some reasons:

- By stage 2, you have a professional proofreading qualification (perhaps from the Society for Editors and Proofreaders or The Publishing Training Centre, since both of these are known and respected bodies in the mainstream publishing industry).

- You have teaching experience, so you’re used to working to fixed lesson timetables (think production schedules), following curricula to the tee (think editorial briefs), are good at working with people – albeit small ones – who need careful handling (think sensitive authors), and are used to working to rigorous educational key-stage standards (think publishing industry).

- You understand the language of academia (your degree) and the language of learning (education), so you’re already primed for academic publishing.

- You’re (naturally!) prepared to take a proofreading test to demonstrate the skills you’ve learned and prove that you’re ready to hit the ground running.

- Your education degree and career experience mean you know the language of education theory and practice. That means that for education publishers you have a USP that I don’t (with my Politics degree).

And who are those education publishers?

Google is your friend here, but here’s a short list of publishers in the UK who have education lists or imprints. In your position, I’d start by getting in touch with every single publisher you can find in the UK who publishes education content.

- Bloomsbury

- Cambridge University Press

- Collins

- Edward Elgar

- Heinemann

- Hodder Education

- Macmillan Education

- McGraw-Hill Education

- Out of House Publishing (packager)

- Pearson Higher Education and Professional

- Policy Press

- SAGE Publications

- Scholastic

My bet is that most (many, certainly) academic or scholarly publishers in the UK will have books, journals and electronic products in the field of education at some level.