|

What is flash fiction and can its creation make us better writers and better editors?

In July 2018, I wrote my first piece of flash fiction and submitted it to the Noirwich Crime Writing Festival’s flash fiction competition. Here’s what I learned.

What is flash fiction?

Think of a tiny story that packs a large wallop … that’s flash fiction. It’s not always called that. Some call it micro fiction, others nano fiction. I’ve also heard it called the shortie, short-short and postcard fiction. How long is it? There’s no consensus other than it’s short ... very short. Some types of flash fiction have established word counts – the dribble with 50 words, the drabble with 100 words, and Twitterature – no more than 280 characters. If Twitterature seems like a challenge, imagine writing it when the character-count limitation was 140! So what are the key components and what can they teach writers of longer-form fiction? 1. Brevity – making every word count Keeping things tight is one of the biggest challenges faced by many of the beginner novelists I work with. Overwriting usually occurs because the author hasn’t yet learned to trust their reader. Will that single adjective be enough? Maybe another sentence that says a similar thing would be in order, just for clarification … Often, it’s not a reflection of a writer’s ability to write, but about confidence. Getting the balance right comes with experience and not a little courage. A line editor can help with overwriting – they bring fresh eyes to the book, and can advise on what can safely be removed without damaging flow, sense, rhythm and tension, and in a way that respects style and voice. Flash fiction helps writers practise the art of precision in the extreme. And when it comes to self-editing your novel, you can ask yourself this: ‘If this were a short story and my word count was restricted, is this the way I’d construct this sentence?’ The answer might be ‘No, but I’d be missing an opportunity to enrich the narrative and the dialogue in a way that’s best for my book.’ That’s a great answer. Still, the flash fiction writer is forced to be disciplined, and when it comes to writing longer works, that discipline will get you used to thinking in terms of making sure every word counts, and comfortable with removing those that don’t. A limited word count also encourages writers to experiment with literary devices such as free indirect speech, sentence fragments, action beats, and asyndeton, all of which can facilitate brevity but enrich tension, immediacy, mood and rhythm.

2. Structure – shaping the story

Stories need structure. No writer wants to get to the end of their novel only to realize that the denouement occurred ten chapters earlier. Sophie Hannah calls it ‘story architecture’, which I think is both a practical and a beautiful way of thinking about how a writer helps their readers experience a novel. There are different ways to shape stories but the most common is the three-act structure. First, the beginning or hook that draws us in. Second, the middle where the confrontation takes place. This is where we come to understand the characters’ motivations and the conflict or obstacles in their way. Third, is the end where the denouement or resolution occurs. Says Julia Crouch, ‘If you have any storytelling bones in you at all, you will more than likely, even subconsciously, end up with a structure like this.’ How does flash fiction help? Do you even need to worry about structure when you’re writing such a short piece of work? Absolutely! No one will enjoy an 80,000-word novel that’s poorly structured. The same applies to 800 words. The only difference is that with flash fiction they’ll lose interest quicker. Flash fiction is a story form in its own right. It’s not about pulling an excerpt from a longer-form piece of writing. Flash must have structure – a beginning, a middle and an end. Something must happen to someone or something, and readers must leave the story feeling satisfied, that the story is complete, that they’ve been on a journey, albeit a short one. Without structure, it will descend into nothing more than an extract. Perhaps flash is akin to poetry – squeezing big ideas into small spaces. That too, though, is good practice for the novelist, because it encourages writers to think about the discipline of shaping, and the journey that the reader will be taken on.

3. Strong endings – surprises and twists

There’s nothing more disappointing than a book that hooks you into turning page after page only to sag into a giant anti-climax. ‘Endings are so important to the reader and you will never please everyone,’ says Nicola Morgan. ‘Readers do want the end to feel “right”, though. They have spent time with these characters and they care what happens to them.’ How and when novelists decide to tie up all or most of the loose ends will depend on style, genre, and whether the book is part of a series, but there must be some sort of closure so that your readers aren’t left hanging. Flash fiction is a challenge to write, but it’s a challenge to read too, particularly for those who love to get stuck into a world and the characters who move around within it. It’s therefore an excellent format in which to practice packing a final punch, even if that amounts to just one or two sentences. This form of writing also allows writers to play with readers’ expectations of resolution in quirky ways. You might decide to evoke a laugh, or a shudder, or shock, or a sense of poignancy, but the reader should feel something such that even though you’ve only written a few hundred words the story is memorable. Here are some additional tips that you might consider if writing flash fiction appeals.

Flash fiction tips #1: Seek immediacy

Which tense will you use? At the time of writing, I’ve written eight flash fiction stories, none of more than 900 words. In all but two I instinctively opted for the present tense. I didn’t notice my predilection until I reread them one after the other. It made me reconsider the two I’d framed in the past tense. I decided to see what would happen if I changed them. I learned something. My narrative tension loses its piquancy when I write in the past. That’s not to say I wouldn’t use the past if I were writing a novel. However, for flash fiction, there’s no time to lose! I’m trying to close the distance between the reader and the viewpoint character so that the former is quickly immersed in the tiny world I’ve built. The opposite might be true for you; there are no rules. But if your flash is flagging, don’t be afraid to experiment with tense and evaluate the impact. Flash fiction tips #2: Characters and viewpoint Given the space available, keep the story tight by sticking to one viewpoint character. It’s easier to create immersion if you allow readers to get under the skin of a single person’s experience. That doesn’t mean there can’t be other characters in the frame, just that we see these others through the viewpoint character’s eyes. You’ll likely need to omit anything about the character that isn’t necessary to drive the story forward. Novels include descriptions of the characters’ appearance and personality so that we can better visualize them and understand their motivations. With flash, consider focusing only on those unique physical and emotional traits that nudge the reader towards the big reveal. Flash fiction tips #3: Use the mundane Play the what-if game. Take an object, or place, or personality attribute of someone you know, and ask what the story might be in another universe. What if that old door in your friend’s hallway didn’t really go to the downstairs loo? What if that scribble you found on the inside of a library book had a more sinister connotation? What if your neighbour wasn’t quite who you believed them to be? What if your best mate’s boring job was just a cover story? Sometimes the most wonderful clues to the theme of a shortie are hidden in plain sight. 4. The editor turned fiction writer – lessons learned Writing and editing are two very different arts. I don’t believe that a good fiction editor must be a fiction writer. I do, however, think we need to understand the core components of fiction writing and what makes a book work, and be able to place ourselves in the shoes of the author and the reader. Still, I’m (now) one of many fiction editors who also write fiction. Some of my colleagues have publishing contracts. Some are self-publishers. Some have agents, while others are seeking representation. Some of us write our fiction purely for pleasure. There are many roads, but we all agree on one thing: it has been good for us to sit on the other side of the desk – to be the writer, to be the one being edited.

Louise reading 'Zeppelin'. Crime writer Elizabeth Haynes looks on.

The short story I wrote for Noirwich 2018 was a challenge for two reasons:

The amazing thing is that I made the final shortlist of three. That, however, presented a new challenge. I was invited to Noirwich Live where the winner would be announced by New York Times bestseller Elizabeth Haynes. Would I read my story ‘Zeppelin’ to a roomful of people, mostly complete strangers? The audience comprised fellow amateur writers, teachers of creative writing, published writers including Haynes, Merle Nygate and Andrew Hook, and most important of all, my daughter Flo and dear friend Rachel. My knees might have been trembling as I took to the floor, but I got the job done and thought about what I’d learned from the experience. Sharing takes courage Writing fiction is one thing; sharing it with others is quite another. Even tiny fiction like mine. For some of us, it takes courage, especially when massive doses of newbie impostor syndrome are flowing through one’s veins. And this is exactly how many of my author clients feel. Sometimes I’m the first person on the planet to see their work when they’re done with it. My experience enhanced my already deep respect for them, because now I know how it feels to share my fiction with others. Editing is an honour My own small venture has taught me what a privilege it is to be chosen by an author to edit for them. When they choose me or one of my colleagues, they take a leap of faith. They place trust in us to treat their words with respect and help them move forward towards their publishing goals. Fiction is intimate The nine stories I’ve written to date are really short. I’m at the beginning of my fiction writing journey. I have a lot to learn. But those stories are precious to me. Every one of them contains a bit of me, or of someone I care about, or someone or something that has made a mark on me in some way. They are not fact, but they are not completely made up either, and that infuses them with a level of intimacy. In other words, fiction writing is personal. It’s important that the fiction editor takes all of that into their editing studio and remembers it at every touchpoint of the project – an amendment, a query, a summary – and never forgets to say thank you.

Further reading

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

0 Comments

Dialogue tags – or speech tags – are what writers use to indicate which character is speaking. Their function is, for the most part, mechanical. This article is about how to use them effectively.

A dialogue tag can come before, between or after direct speech:

Placed in between direct speech, tags can moderate the pace by forcing the reader to pause, and improve the rhythm by breaking up longer chunks. Rather than give you a bunch of zombie rules that you’ll want to break about two seconds after you’ve read them, here are three guidelines to bear in mind when thinking about which tags to use, which to avoid, and when you might omit them altogether:

Why said often works best, and when it’s not enough The speech tag said ‘is a convention so firmly established that readers for the most part do not even see it. This helps to make the dialogue realistic by keeping its superstructure invisible,’ say Mittelmark and Newman in How Not to Write a Novel (p. 132). I agree, and I recommend you embrace it! If someone’s told you to avoid repeating said, head for your bookshelf and take a peek inside some of your favourite novels for reassurance. If you deliberately try to avoid said, you run the risk that your writing will reflect that intention. If your reader is focusing on your avoidance, their focus is not where it should be – on your story. Still, there will be times when you’ll want a tag that tells your reader about, say, the sound quality, the mood of the speech, or the tone of voice. Speech tags aren’t the only way to do this – for example, you could use action beats before the dialogue, or adverbial phrases after your tags – but few readers will complain if you use the likes of whispered, yelled, shouted, muttered or whined. Hissed is one that I rather like, though some writers and editors are less keen. Even though said 's invisibility makes it harder to overuse, avoid the temptation to place it after every expression. Here’s an example of how it looks when it's been overworked (see, too, the final section in this article, ‘Omitting dialogue tags’):

EXAMPLE: OVERUSE OF SAID

‘Tag it,’ he said. ‘Why?’ she said. ‘Because it’s the right thing to do,’ he said. ‘I suppose you’re right,’ she said. 'I'm glad you agree,' he said. Showy speech tags and underdeveloped dialogue Showy tags can overwhelm dialogue. Since you’ve written your dialogue for a reason, that’s where the reader’s attention should be. When the tag is more visible than the speech, it’s a red flag that the dialogue, not the tag, needs enriching:

EXAMPLE: SPEECH TAG OVERWHELMS THE DIALOGUE

‘The way he was dressed, the attack was inevitable,’ preached McCready. Instead, we might amend the dialogue so that it conveys the preaching tone, and leaves the tag (said) with the mechanical function of indicating who’s speaking:

EXAMPLE: ENRICHED DIALOGUE; SIMPLER SPEECH TAG

‘Oh, come on,’ McCready said. ‘You dress like that, you’re going to attract the weirdos. Just the way it is. He had it coming, no question.’ Showy speech tags and double-telling Some speech tags are just repetitions of what the reader already knows – they double-tell. Asked and replied are two common examples, though these are used so often that they don’t fall into the showy category. For that reason, I don’t think you need to go out of your way to avoid these, though do take care not to overuse them. Showier examples – such as opined, commanded, threatened – become redundant if you’ve got the dialogue right:

EXAMPLES: SHOWY SPEECH TAGS THAT DOUBLE-TELL

‘But it’s none of our business how Jan makes her living,’ opined Jack. ‘Stand down, soldier! That’s an order,’ the general commanded. ‘If you tell a soul what you heard here today, I swear I will kill you and everyone you have ever loved,’ Jennifer threatened. ‘That’s amazing!’ he exclaimed. In the first three examples, it’s clear from the dialogue that an opinion, a command and a threat have been given. The speech tags repeat what we already know; we should consider whether said is a less invasive alternative. In the fourth example, amazing and the exclamation mark (!) tell us that the speaker exclaimed, so again the showy tag is redundant. It’s a question of style, of course. I’m not giving you rules but suggesting ways of thinking about the function of your tagging so that you keep your reader immersed in the spaces of your choosing. Non-speech-based dialogue tags and the reality flop Even if you decide you do want a more extravagant tag than said, take care when using verbs that are not related to the mechanics of speaking. Examples include: smiled, gesticulated, ejaculated, thrusted, fawned, scowled, winced, smirked, sneered, pouted, frowned, indicated and laughed. The physicality of these verbs will jar your reader and they immediately introduce an element of inauthenticity into the prose. They’re great words for describing what other parts of a person’s body can do, but are unsuitable for use as dialogue tags:

EXAMPLES: UNSUITABLE NON-SPEECH-BASED TAGS

‘Martin, you’re not seriously going to wear that, are you?’ she laughed. 'You,' she smiled, 'are the best thing that's ever happened to me.' Try one of the following instead:

EXAMPLES: ACTION BEATS AND ADVERBS; SIMPLER OR OMITTED SPEECH TAGS

‘Martin, you’re not seriously going to wear that, are you?’ she said, laughing. [Uses laughed adverbially.] She laughed. ‘Martin, you’re not seriously going to wear that, are you?’ [Uses laughed in an action beat.] 'You' – she smiled – 'are the best thing that's ever happened to me.' [Uses smiled in a mid-sentence action beat. Note the spaced en dashes. If you were styling according to US convention you could opt for double quotation marks and closed-up em dashes.] Alternatives to showy speech tags – more on action beats Rich action beats can complement or even replace speech tags, and are useful if you want to keep your dialogue lean and are tempted to use a showy speech tag. Keep them on the same line as the speaker they’re related to. Action beats let you set the scene so that the reader can fill in the gaps with their imagination while a character is speaking. Here’s an example of dialogue with a showy speech tag – moaned:

EXAMPLE: SHOWY SPEECH TAG

‘My back teeth are killing me,’ James moaned. In the alternative below, the reader can discern the moaning manner in which the speech is delivered because James’s discomfort is shown in the action beat preceding it:

EXAMPLE: ALTERNATIVE USING ACTION BEAT

James pressed two fingers to his cheek and winced. ‘My back teeth are killing me.’ Notice how the action beat is punctuated. There’s a full stop (period) after winced. Neither of these examples is wrong or right. You might decide that you prefer one over the other. Rather, I’m showing you alternatives so that you can make informed decisions about how to make your writing engaging. Using proper nouns in dialogue tags If your fiction is gender binary (and it might well not be) and the genders are known to the reader, you needn’t repeat the speaker’s name every time they appear in a dialogue tag. You can use third-person singular pronouns: he and she. Clarity is everything here. Notice how Alexander McCall Smith uses nouns and pronouns in his dialogue tags, and peppers the text with action beats so that the reader knows who’s speaking (The No.1 Ladies’ Detective Agency, p. 125):

EXAMPLE: MIXING UP PRONOUNS AND PROPER NOUNS

Mma Ramotswe nodded her head gently. Masculine bad behaviour. ‘Men do terrible things,’ she said. ‘All wives are worried about their husbands. You are not alone.’ Mma Pekwane sighed. ‘But my husband has done a terrible thing,’ she said. ‘A very terrible thing.’ Mma Ramotswe stiffened. If Rra Pekwane had killed somebody she would have to make it quite clear that the police should be called in. She would never dream of helping anybody conceal a murderer. ‘What is this terrible thing?’ she asked. Mma Pekwane lowered her voice. ‘He has stolen a car.’ [...] Mma Ramotswe laughed. ‘Do men really think they can fool us that easily?’ she said. ‘Do they think we’re fools?’ ‘I think they do,’ said Mma Pekwane. Omitting dialogue tags If you’re confident your reader can keep track of who’s saying what in a conversation, you can omit dialogue tags altogether. Once more, it’s not about rules but about sense and clarity. This will work best if there are no more than two characters in the conversation, and even then, most writers don’t extend the omission for more than a few back-and-forths before they introduce a reminder tag or an action beat. Here’s an example from Peter Robinson’s DCI Banks novel Sleeping in the Ground (pp. 273–4). There are two characters in this scene: Banks and Linda. Robinson omits most of the dialogue tags in this conversation because it’s clear who’s speaking, but he keeps us on track with an action beat and a tag halfway through:

EXAMPLE: KEEPING THE READER ON TRACK

‘So do I,’ said Banks. After a short pause he went on. ‘Anyway, I seem to remember you told me you went to Silver Royd girls’ school in Wortley.’ ‘That’s right. Why?’ 'Does the name Wendy Vincent mean anything to you?’ ‘Yes, of course. She was the girl who was murdered when I was at school. [...] It was terrible.’ Banks looked away. He couldn’t help it, knowing the things that had happened to Linda, but she seemed unfazed. ‘That’s right,’ he said. ‘And there was something about her in the papers a couple of year ago. The fiftieth anniversary. Right?’ ‘That’s the one.’ ‘It seems a strange sort of anniversary to celebrate. A murder.’ ‘Media. What can I say? It wasn’t a [...]’ Summing up When it comes to dialogue, remember the function of the tag: to indicate which character is speaking. Says Beth Hill, ‘These tags are background, part of the mechanics of story; they meet their purpose but don’t stand out. They let the dialogue take the spotlight’ (The Magic of Fiction, p. 166). So, during the self-editing process:

Cited sources and further reading

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Good proofreading practice means acknowledging that changing one word, or moving one line, can have unintended and damaging consequences throughout the rest of the book if we aren’t careful.

If we want to proofread for publishers, packagers and project-management agencies, or if we're checking self-publishers' print-on-demand books, we need to be comfortable with working on page proofs.

What are page proofs? The proofreader will usually be asked to work on page proofs. What are they?

'Page proofs are so-called because they are laid out as exactly as they will appear in the final printed book. If all has gone well, what the proofreader is looking at will be almost what the reader sees if they were to walk into a bookshop, pull this title off the shelf and browse through the pages.

The layout process has been taken care of by a professional typesetter who designs the text in a way that is pleasing to the eye and in accordance with a publisher’s brief.' (Not all proofreading is the same: Part I – Working with page proofs) In this case, the proofreader does not amend the text directly. They annotate the page proofs. You might be required to work on both hard-copy page and PDF page proofs – it will depend on the client’s preference. You'll be looking for any final spelling, punctuation, grammatical, and consistency errors that remain in the text. However, you'll also expected to check the appearance of the text. Checks will include the following:

This isn't a comprehensive list but it gives you an idea of how this type of proofreading goes beyond just checking the text for typos. If your client hasn’t supplied you with a proofreading checklist, you can access this free one when you sign up for The Editorial Letter.

What's important here is that every amendment you suggest might have an impact somewhere else. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t make the amendment; it means, rather, that you need to be mindful of the consequences of your actions – the knock-on effects.

What are knock-on effects? Professional proofreaders often refer to the indirect consequences of their mark-up as knock-on effects. A useful way of thinking about this is in terms of dominoes because it provides us with the perfect description of what’s at stake. Imagine you've lined up four dominos: A, B, C, and D. You push over A and it pushes over B. B then knocks over C, which in turn causes D to fall. Domino D’s topple was caused indirectly by Domino A, even though A didn’t touch D. This process can occur on page proofs and can have serious consequences. The changes we make can, if we’re not careful, impact on the text flow, the pagination, the contents list, and the index.

An example

Here’s an example to illustrate the point. Imagine the publisher’s brief tasks the proofreader with attending to orphans and widows (those stranded single lines at the bottom or top of a page). Solutions that involve instructing a typesetter to shuffle a line backward to a previous page, or forward to the next page, in order to avoid the widow/orphan might cause one, or all, of the following problems:

In all three cases, the proofreader has prevented one problem but caused others. Consequently, good practice involves more than blindly placing mark-up instruction on any given page. Thought needs to be given to how the problem can be tackled and the impact managed so that there is no knock-on effect. Spotting an orphaned or widowed line is not enough. We might also have to consider the following:

Summing up If you’re considering training as a proofreader and want to be fit for the purpose of marking up page proofs, check that your course includes a component about knock-on effects. Even when we are supplied with detailed briefs about an ideal layout, the publisher client expects us to be mindful of the consequences of our amendments. The proofreader’s job is to find solutions to problems in ways that don’t cause unintended damage.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

If you’re including authentic technical or procedural information in your crime writing, you’ll be wearing your research hat. Your story should come first, of course. However, be sure to get your facts straight before you decide if and how far you’re going to bend reality.

Procedure varies between region and country, and when your novel is set will also determine the relevance of the resources I’ve included. Still, even those outside your jurisdiction might spark an insight that drives your storyline further or deepens your characterization

Conversations, consultations and ride-alongs

My brushes with the law have been limited to bad parking. Still, I know a few coppers socially, and it’s to them I’d head for procedural guidance in the first instance. If you know a police officer, a forensic anthropologist, a crime-scene investigator, a barrister, or whatever, ask them if you can pick their brains. They’ll have expert subject knowledge and insights, and your talking with them face to face could be the most powerful tool of all. If you don’t have existing contacts, ask your friends for theirs or put a call out on social media. A writer recently requested help from munitions experts via the Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi) Facebook group. Several commenters provided advice and one offered to put her in touch with an expert. If your book's set in the UK, try Consulting Cops or Graham Bartlett, author and crime fiction advisor. Both have teams of law-enforcement experts who'll help you keep your facts straight. Here’s crime writer Julie Heaberlin discussing the importance of researching and feeling comfortable approaching experts, especially to bring deeper layering to her novels:

‘I’m very worried about not being accurate […] because there are a lot of writers who don’t research and that’s just more misinformation out there. And I learn things myself. Standing outside the Texas Death House during an execution … it wasn’t anything like I thought it would be.’

How to Write Crime – Harry Brett in conversation with Sophie Hannah and Julia Heaberlin. Waterstones, Norwich, 2018

In a bid to improve relations between the police service and the public, some larger forces now operate ride-along schemes that allow members of the public to patrol with an officer. In the UK, these include Avon & Somerset, Nottinghamshire, Essex, Lincolnshire, Lancashire, Humberside and Warwickshire Police.

Search online using the keywords ‘ride-along police [your country/state/city]’ and see what comes up.

Watch and read

How about TV and movies? Your favourite crime dramas and fiction might have been meticulously researched. Then again, they might not. In ‘Five Rules for Writing Thrillers’ David Morrell urges writers to do the research but to use caution:

‘You don’t need to be a physician or an attorney to write a medical thriller or a legal thriller, but it sure helps if you’ve been inside an emergency ward or a courtroom. Read non-fiction books about your topic. Interview experts. If characters shoot guns in your novel, it’s essential to fire one and realize how loud a shot can be. Plus, the smell of burned gunpowder lingers on your hands. Don’t rely on movies and television dramas for your research. Details in them are notoriously unreliable. For example, the fuel tanks of vehicles do not explode if they are shot. Nor do tires blow apart if shot with a pistol. But you frequently see this happen in films.'

Morrell talks more about how research makes him ‘a fuller person’ and how he learned to fly in order to create an authentic pilot for his book The Shimmer. The expense of a pilot’s licence will probably be out of reach for the average self-publisher. YouTube could be the solution.

There are thousands of hours’ worth of real-life video footage on YouTube. You can learn from experts about how a body decomposes, how an autopsy is carried out, how a forensic sketch artist works, and how to clean up a crime scene.

And there are lectures on the science of blood spatter, computer forensics, investigation techniques, and forensic imaging. You name it, it’s probably there.

Use Wikipedia

Wikipedia is great for any sleuthing writer wanting to track down information about criminal procedure. Do, however, use the primary sources cited in the references to verify the information. In the online masterclass ‘How to Write a Crime Novel’ Dr Barbara Henderson recommends using at least two sources for internet-verification purposes. Here are some searches to get you started:

Security agencies

MI5 – the UK’s homeland security service

Visit the official site of MI5. There’s information on how it handles covert surveillance, communications interception, and intelligence gathering, plus a brief overview of its history since its creation in 1909. Christopher Andrew’s The Defence of the Realm is the first authorized history of the service. Published by Penguin in 2010, it’s available on Amazon and in major bookstores. Visit The National Archives and type MI5 into the search box. That will give you access to all the files that have been released into the public domain to date. National Crime Agency (UK) The NCA is tasked with protecting UK citizens from organized crime. Its website has articles and reports about cybercrime, money laundering, drugs and firearms seizure, bribery and corruption, and trafficking. I recommend looking at the NCA’s free in-depth but readable reports such as the National Strategic Assessment of Serious and Organised Crime 2018, which outlines threats, vulnerabilities, the impact of technology, and response strategies. MI6 (SIS) – the UK’s secret intelligence service Visit the official website of the SIS to find out how it handles overseas intelligence gathering and covert operations. There’s a brief overview of the service’s history and some vignettes that illustrate how intelligence officers operate. Keith Jeffery’s MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909–1949 is ‘the first – and only – history of the Secret Intelligence Service, written with full and unrestricted access to the closed archives of the Service for the period 1909–1949’. If you want historical information, this is a good place to start. GCHQ – Government Communications Headquarters (UK) The GCHQ website is worth visiting just to see the building from which it operates in Cheltenham! There’s an overview of GCHQ history, operations, its various operational bases, and how it works with Britain’s other security services to manage global threats. For a more in-depth study of the service, start with Richard Aldrich’s GCHQ: The Uncensored Story of Britain's Most Secret Intelligence Agency. FBI – Federal Bureau of Investigation (USA) The FBI’s website is packed with the usual overview material of how and why, but I think the go-to resources are the likes of the free Handbook of Forensic Services, the Terrorist Explosive Device Analytical Center (TEDAC) page, and the training guidance. The easiest way to navigate around the site is to head to the FBI home page and scroll down to the links in the footer. NSA – National Security Agency The NSA website is the place to go for twenty-first-century code-breaking information, and there’s a ton of information about cybersecurity and intelligence. Head for the Publications section to get free access to The Next Wave and various research papers. The material is dense but could be just the ticket for building backstories for cybergeek characters.

Police forces

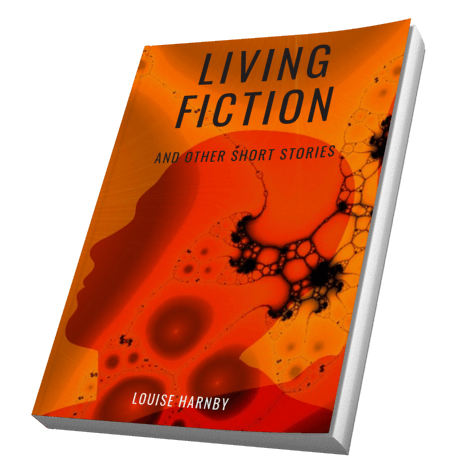

Michael O'Byrne is a former police officer who worked in Hong Kong, and later with the Metropolitan Police (sometimes referred to as New Scotland Yard). Try the second edition of his Crime Writer's Guide to Police Practice and Procedure. INTERPOL This is the world’s largest police force with nearly 200 member countries. The Expertise section of its website is rammed with useful and readable information on procedure, technical tools, investigative skills, officer training, fugitive investigations, border management and more. UK police forces Police procedure will vary depending on where you live. You can access a list of all UK police force websites here: Police forces, including the British Transport Police, the Central Motorway Policing Group, the Civil Nuclear Constabulary, the Ministry of Defence Police and the Port of Dover Police An Garda Síochána – Ireland’s national police and security service The easiest way to navigate the Garda’s website is to head for the home page and scroll down to the sitemap at the bottom. There you’ll find links to information on policing principles, organizational structure, and the history of the service. The Crime section is particularly strong on terminology and procedure. Legal resources Lawtons Solicitors’ website has an excellent Knowledge Centre filled with articles on parliamentary acts, offences, criminal charges and police procedure. What are the drug classifications in the UK? and Police Station interviews are just two examples. Ann Rule’s advice on attending trials is aimed at true-crime writers, but you could use the guidance for fictional inspiration: Breaking Into True Crime: Ann Rule’s 9 Tips for Studying Courtroom Trials. Crown Prosecution Service (UK): The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) website provides detailed prosecution guidance for criminal justice professionals. It is extremely dense, and so it should be; it wasn’t designed for novelists! See, for example, the section on Core Foundation Principles for Forensic Science Providers: DNA-17 Profiling. Still, there’s a wealth of information there for those prepared to wade through it. Department of Justice (USA): The DOJ site offers guidance on the role of the Attorney General, the organizational structure of the department, lots of statistical information, and maps of federal facilities.

Forensics resources

Historical crime writing resources

Weapons research

I hope you find these resources useful. I’ve barely been able to scratch the surface, not least because I’m busy trying to book a ride-along with my local bobby! While I sort that out, here’s some wise advice from David Morrell:

‘The point isn’t to overload your book with tedious facts. Rather, your objective is to avoid mistakes that distract readers from your story. If you’ve done your research, readers will sense the truth of your story’s background. In addition, the topic should interest you so much that the research is a joy, not a burden.'

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses. |

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed