|

Here’s how to build a knockout editing portfolio page even if you’re relatively new to the field.

Deciding what to include, what to omit, and how to lay it out so that it grabs a potential client’s attention can be tricky. If your business is new you might not have a lot to shout about. If you’re established, you might have too much.

One thing’s for sure, though – an editing site without a visible portfolio is at a disadvantage. It’s the next best thing to the social proof of a testimonial because it demonstrates that you practise what you preach. Using stories is a method every editor can use to bring their portfolio page to life. Moving from mechanics to emotions Stories are lovely additions to any portfolio page because they give us the opportunity to take our potential clients behind the scenes ... to show them how we helped and how the project made us feel. That’s important because it shifts the attention away from mechanics and towards emotion. Those of us who work with non-publisher clients such as independent authors, academics, businesses and students are asking our clients to take a big leap ... to put their project in the hands of someone they’ve never met, and pay for the privilege. It’s a huge ask and takes not a little courage for some. Think about it from the client’s point of view:

These clients will be looking for an editor they can trust, someone who gets them, understands what their problems are and can solve them without making a song and dance about it. Trust is something that is usually earned over time – think about your friendships and partnerships. Editors and their clients don’t always have the luxury of time. What’s needed is something that will fast-track the growth of trust. Word-of-mouth recommendations are fantastic for this. Testimonials from named clients are also excellent social proof. Portfolios work in the same way. The problem is, they can be boring.

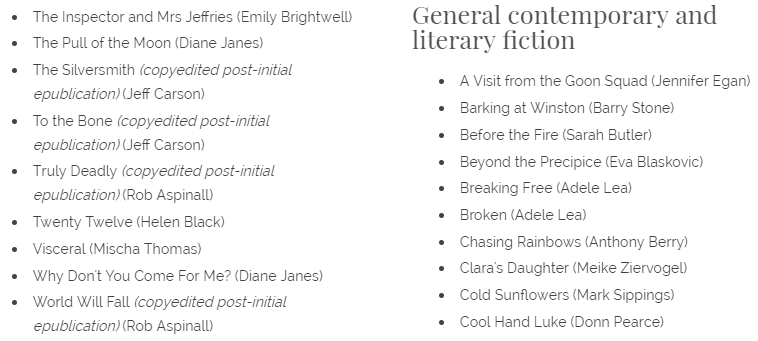

A partial screenshot of my boring but useful list!

The list: boring but powerful I’m not going to suggest you dump your long lists. Boring though they may be, I believe there’s power in them, and for two reasons:

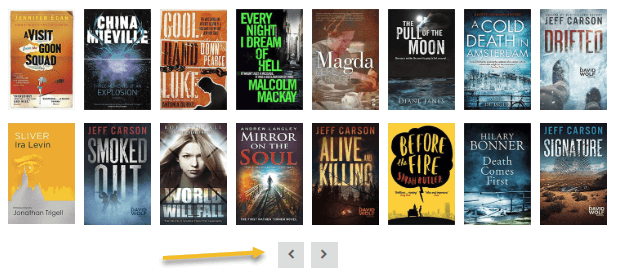

So, if you want to keep your long lists, do so. I have. Make them more accessible and aesthetically pleasing by breaking them into subjects or genres. Add thumbnails of book jackets, journal covers or client logos (subject to securing permission from the client). Use a carousel or slideshow plug-in to show off multiple images without cluttering up the page.

Adding pizzazz with stories

Now it’s time to add the wow factor. Stories take the portfolio one stage further. They’re basically case studies of editing and proofreading in practice. Can you recognize yourself in the following list?

Stories work for all three groups of editors:

What to include It’s up to you what you include but consider the following:

Example 1

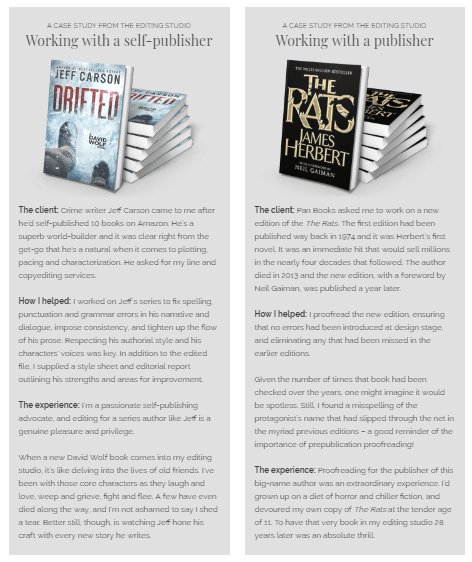

I’m a fiction editor who works for a lot of first-time novelists. Many haven’t worked with an editor and don’t know what to expect. Some feel anxious and exposed. My two portfolio stories have a friendly, informal tone. One of my case studies focuses on a self-publishing series author whose fictional world I’ve become close to. By showing how we work together and how his writing makes me feel, I demonstrate my advocacy for self-publishing and the thrill I get from working with indie authors, the emotional connection I make with the characters, and the delight I experience in seeing writers hone their craft.

Two case studies from the editing studio

Example 2

If you work with corporates, your stories might have a reassuring, professional tone that conveys confidence and pragmatism. Your case studies could feature clients whose projects required the management of privacy and confidentiality concerns. You could use the space to talk about the challenges you faced and the successes you and your clients achieved even though the projects were complex and demanding.

Example 3

If you work with publishers, you could create case studies that show how you managed tight deadlines, a controlled brief, and a detailed style guide. The stories could highlight some of the problems you and the publisher overcame, your enthusiasm for the subject area, the pride you felt on seeing the book published, knowing the part you’d played in its publication journey. Crafting stories about relationships If your home page is all about the client, the portfolio page can be all about relationships. By crafting stories for our portfolios, we can invite potential clients onto the stage and let them experience – if only fleetingly – editing in action. And because the case studies are real, they’re a powerful tool for knocking down barriers to trust. They show a client how we might help them, just as we’ve helped others.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

4 Comments

If you're self-publishing within a strict budget, this booklet will help you decide how best to invest.

The guidance is broken down into sections that reflect the recommended order of play and the outcomes you want to achieve.

Click on the image to download your free copy.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Some crime writers are planners. Some are pantsers (so called because they fly by the seat of their pants). Neither is better than the other. What matters is that the method you choose to write your story works for you and results in a tale well told.

Being either a planner or a pantser won’t determine whether you sell lots of books. A story that makes sense – one that reads as if you had carefully planned it – is what’s key to creating an experience that readers will relish.

So what do some of the big-name crime writers have to say on the matter? What’s right for you? ‘The more I talk to other crime writers the more I start to become fairly sure that for each writer there is an ideal way, but there isn’t one ideal way,’ says Sophie Hannah. I think I’ve read everything Harlan Coben’s ever written. If I haven’t, it’s waiting in the pile or on the Kindle. If you’d asked me, I’d have marked him as a planner. His stories hang together so well; he ties up every loose end. And I always have that ‘Ah, that’s what happened’ moment. But in fact, Coben’s a pantser:

'I don’t outline. I usually know the ending before I start. I know very little about what happens in between. It’s like driving from New Jersey to California. I may go Route 80, I may go via the Straits of Magellan or stopover in Tokyo … but I’ll end up in California.'

Maybe you’re like him or Julia Heaberlin:

‘I start with just a fragment of a thought in my head. I don’t outline at all. I have no idea where the book is going.'

Or perhaps you’re like Susan Spann:

‘My novels start with an outline, and that outline starts with the murder – even when the killing happens before the start of the book.'

Or Hannah:

‘When I start writing chapter 1, I have a 90–100-page plan … kind of like a list of ingredients of what needs to happen in each chapter. And I don’t write it well. I don’t write it elegantly. It could be written by a robot […] but everything necessary for that chapter, whether it’s a murder or a snide glance, is included in that plan.'

To help you decide whether to plan or pants, consider the following:

Planning and creativity

Some writers fear that planning will mute their creativity and the process of discovery. The following excerpt is from an article from the NY Book Editors blog:

‘For writers striving to create something unique and surprising, the kind of work that will grab the attention of agents and editors, the thorough plotting and planning can be a matter of life and death. By that, I mean that planning your novel ahead of time increases its likelihood of being dead on arrival. […] When writers engage in extensive pre-writing in the form of outlines and character sketches, we change the job of the writing we’re preparing to do. All of a sudden our role becomes that of the translator.'

Heaberlin feels that surrendering control to her characters is essential to the creative unfolding of her stories:

‘I let the characters kind of take me wherever they want me to go. It sounds a little precious but that’s what happens. The plot evolves through the characters telling me what’s going to happen next.'

However, passionate planners feel differently. Their plans are as much a form of artistry as the actual writing. Here’s Hannah on how a plan needn’t thwart spontaneity:

‘Plot and character are not rivals – they’re co-conspirators […] The biggest lie uttered by writers about planning is that it somehow limits or stifles creativity. This is absolutely untrue. Planners simply divide their writing process into two equally important and creative stages: story architecture, and actual writing. Both are fun. And yes, of course you can make as many changes as you want when you come to write the book – I’ve changed characters, endings, plot strands, everything very spontaneously, even with my plan at my side, when it’s felt like the right thing to do.'

Time frame and process

Some authors write multiple drafts to ensure the book’s plot works. That slows down the process. Hannah’s detailed planning approach means her first draft works; she’s already identified where the problems are before she gets started on the actual writing process.

‘A lot of the thriller-writers I know who turn up their noses at planning end up writing four or five drafts of their novel before they’re happy with it. You might want to do that – in which case, you should do it! – but if you’d like to spend one year writing a book rather than five, planning is the way forward.'

Jeffery Deaver concurs:

‘I plan everything out ahead of time. I work very hard to do that. Part of that is planning each subplot – I call it choreographing the plots. I start with a post-it note. I put it in the upper left-hand corner [of my whiteboard] and that’s my opening scene. And then I start to fill in post-it notes throughout the whiteboard. Then I come up with a big idea for the twist, and that goes in the lower right-hand corner. And if that’s going to be a legitimate twist, that means planting clues.'

He then walks around talking to himself, deciding where on the whiteboard the clues need to go so that the main plot and various subplots will work. And if he finds that a clue won’t work in a particular place because, say, character X doesn’t know Y yet, he moves the post-it note. It’s an eight-month process but once it’s done, ‘writing comes quickly’. Still, don’t get too comfy! Andy Martin spent the best part of 12 months in the company of Lee Child as he wrote Make Me:

‘Even before he had written the first sentence, he turned to me and said: “This is not the first draft, you know.” “Oh – what is it then?” I asked naively. “It’s the ONLY DRAFT!” he replied.'

Which just goes to show that being a pantser doesn’t necessarily mean being a slow writer.

Does the plot work?

If you’re a pantser, the idea of finding yourself stuck in a hole after months of writing might not terrify you. Lee Child doesn’t let it stop him.

Says Henry Sutton, ‘When, for instance, [Child] hits a cul-de-sac, say his character – Reacher – might be at the point of an impossible situation to get out of, rather than go back and think, “Right, I’ve written too far. I need to delete that chapter or even the chapter before that”, he will think of a way of him actually surmounting that obstacle and then push him on.'

In an interview with Harry Brett, Heaberlin acknowledges the need for third-party assistance to fill in the gaps and polish her stories:

‘In Black-Eyed Susans I did know I wanted to write about mitochondrial DNA but it wasn’t actually until two thirds of the way through that book that I knew I wanted to write about the death penalty! […] At the end, my book is not perfect, not well-crafted. Mine have all these loose ends and so I work with an editor to kind of tidy up. But I also don’t like everything to be answered always, kind of like in real life.'

Contrast that approach with those of these two planners:

Deaver: ‘I know what I’m going to write. In the case of The Cutting Edge, … I knew where all of the subplots went, I knew where the clues were introduced, I knew where the characters entered the book and when they left. […] When I do the outline, I can see whether the book is going to work or not. And if it isn’t going to work then I can just line up the post-it notes and start over [whereas] it can be a very difficult process to start writing and come to page 200 and not know where that book’s going to go.’

Hannah: ‘Without a start-to-finish plan of what’s going to happen in my novel, I don’t know for certain that the idea is viable. It’s by writing a chapter-by-chapter, scene-by-scene synopsis that I put this to the test. I’d hate to invest years or even months in an idea I suspected was great, and then get to where the denouement should be and find myself thinking, “Yikes! I can’t think of a decent ending!”’ What kind of writer are you? In an interview with Henry Sutton in May 2018, Deaver discussed how planning can help the non-linear writer:

‘Writing for me can be very difficult at times. And I have found that doing the outline allows me, since I know the entire schematic of the book, to write the beginning at the end, or the end at the beginning […] So I go to the outline and think: Today I’m supposed to be writing a vicious murder scene but the sun’s out, the birds are singing, and I don’t feel like it. I save it for those days when the cable guy who’s supposed to be coming at 8 in the morning doesn’t show up until 4 and I’m in a bad mood! I can jump around a bit.'

So Deaver’s method allows him to concentrate on telling the part of the story he wants to tell when he wants to tell it. For every writer who frets at the thought of not knowing where they’re going, there’s another for whom that’s a thrill. Child is a linear writer, and Zachary Petit thinks that ‘very well may be the key to his sharp, bestselling prose’.

'When he’s crafting his books, Child doesn’t know the answer to his question, and he writes scene by scene – he’s just trying to answer the question as he goes through, and he keeps throwing different complications in that he’ll figure out later.’

If you too enjoy sharing the rollercoaster ride with your protagonist, pantsing could be the best way for you to tell your story. If not, detailed planning might suit you better. Clue planting Spann has a two-handed strategy for planning. And it’s all to do with the clues. The first outline – the one that will determine what she writes – needn’t be particularly detailed. It’s a map of each scene, and each clue, that enables her to keep her sleuth on track. Just as important, however, is the other outline:

‘A secret outline, for your eyes alone. This one tracks the offstage action – what those lying suspects were really doing, and when, and why. The “secret outline” lets you know which clues to plant, and where, and keeps the lies from jamming up the story’s moving parts.'

I like her on- and offstage approach, and I think it’s particularly worth bearing in mind if you’re a self-publisher who’s not going to be commissioning developmental or structural editing. What you don’t want is to go straight to working with a line or copyeditor and have them tell you your clues don’t make sense, because you’d be paying them to paint your walls even though there are still large cracks in the plasterwork. That offstage outline could help you to complete the build before you start tidying up.

The importance of structure

One thing’s for sure: whether you choose to plan or pants your way through the process, put structure front and centre. Recall my comment above about how Coben always leaves me feeling like he must have had everything worked out from the outset. That’s because however he gets from A to B, he understands structure. Pantsing isn’t about ignoring structure, but about shifting the order of play. Says Deaver:

‘[Lee Child and I] both structure our books. I just do it first. I run into those same roadblocks. And maybe for me it’s a little post-it note […] But the work has to be done somewhere. Any book should be about structure as much as fine stylistic prose.'

And here’s domestic noir author Julia Crouch to wrap things up for us:

‘There is a reason that screenwriting gurus bang on about the three-act structure – setup, confrontation and resolution – and that’s because it works. If you have any storytelling bones in you at all, you will more than likely, even subconsciously, end up with a structure like this. But it’s helpful to bear it in mind and, whether you structure beforehand (as a plotter), or after (as a pantser), run your plot through that mill.'

Good luck with your planning or pantsing! Further reading

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Editors on the Blog is a monthly column curating some of the best posts from the editing community – articles written by editors and proofreaders for colleagues and clients alike.

My thanks to this month's contributors!

THE BUSINESS OF EDITING

CLIENT FOCUS: BUSINESS AND OTHER NON-FICTION

CLIENT FOCUS: FICTION

EDITING IN PRACTICE

LANGUAGE MATTERS

To include your article in next month's edition of Editors on the Blog, click on the button below. The deadline is 16 July 2018.

Louise Harnby is a fiction line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in supporting self-publishing authors, particularly crime writers. She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Society for Editors and Proofreaders (SfEP) and an Author Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi).

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn.

Three questions for you:

If the answer to all three is yes, you’re in marketing heaven!

I’m not kidding you. If you love learning about how to do your job better, and are prepared to make time in your business schedule for this continued professional development (CPD), you have at your fingertips all the marketing tools you need.

Here’s another question: Do you think there comes a point when you’ve learned all there is to learn about being a better editor? If you answered no to that, you’re in even better shape from a marketing point of view because you will never run out of ideas to connect with your target client. And here’s another question: Do you think you have no time in your schedule to learn how to become a better editor? If you answered yes, you need to make time. Every editor needs to continue learning. Our business isn’t static. New tools, resources and methods of working are a feature of our business landscape. Language use changes as society’s values shift. Markets expand and retract, which requires a response from us in terms of how we make ourselves visible. If you answered no, that’s great news because it means you have time for marketing. I know – you don’t like marketing. But that’s fine because we’re not calling it marketing. We’re calling it CPD, which you do like!

Making time for business

Everyone who knows me knows I love marketing my editing business. Lucky me – it’s much easier to do something necessary when you enjoy it. What a lot of people don’t get is how I make time for it and how I get myself in the mindset to devote that time to it. I don’t have a problem with calling it marketing. But the truth is that so much of the marketing I do is not about marketing; it’s about communicating what I’ve researched and learned. I love line and copyediting crime fiction. I think I’m really good at it. But I don’t think I’ve learned everything there is to learn. Not for a single minute. That leaves me with stuff to do. I have to learn. So off I go to various national editorial societies’ websites. I head for their training pages. I look for courses that will teach me how to be a better crime-fiction editor. There aren’t any. I turn to Google. Plenty of help for writers, but not specifically for editors. That’s fine. And so here’s what I’ve done: read books about crime writing, and attended workshops, author readings, and crime-writing festivals (I live a stone’s throw away from the National Centre for Writing and the annual Noirwich festival). And I’ve continued to read a ton of crime fiction. And to help me digest what I’ve learned, I’ve taken notes along the way. It’s what I’ve done all my life when I’m learning – O levels (as they were called in my day), A levels, my degree … notes, notes and more notes. How much time has it taken? Honestly, I don’t know. I’ve been having too much fun. I love reading; I don’t count the hours I spend doing it. How long did the author event last? I’ve no clue. My husband and I had dinner afterwards though, so it was like a date. And it would have been rude to look at my watch.

Is it a blog post?

I wrote a blog post recently about planning when writing crime. I couldn’t churn out 2,000 words just like that; I’m not the world’s authority on the subject. So I referred to my notes from the event with a famous crime writer (the one where I had a dinner date with hubby). Turns out the guy talked about planning, and told us about his and a fellow crime writer’s approach to the matter. I reread a chapter from a book on how to write crime and found additional insights there. More notes. I read 14 online articles about plotting and pantsing too. Yet more notes. And then I put all those notes together, which really helped me to order my thoughts. I created a draft. Redrafted. Edited it. And sent it to my proofreader. Soon I'll publish it and share it in various online spaces. It’ll be on my blog and on the dedicated crime writing page of my website. Some people might call it content marketing. And it is, sort of, because it helps beginner self-publishers work out when they will attend to the structure of their crime fiction – either before they start writing, or after. From that point of view, it is useful, shareable, problem-solving content, which is a perfectly reasonable definition of content marketing.

Or is it CPD?

But look at it another way. I learned a lot of things I didn’t know before. I can use that knowledge to make me a better editor. I took notes and drafted those notes into an article. This is no different to what I did at least once a week at university. I wasn’t marketing then; I was learning. What is different is that no one but my professor was interested in my article. That’s not the case for my planning piece. That article will help some self-publishers on their writing journey. A few might just decide to hire me to line or copyedit for them. It’s happened before. Maybe it will happen again tomorrow, or next month, or next year. I don’t know. It doesn’t matter – the article will stay on my site for as long as it’s relevant.

Change your language

If the idea of marketing your business leaves you feeling overwhelmed, rethink the language you use to describe what’s required. You probably don’t consider attending an editorial conference a marketing activity, even though it might lead to referrals. It’s more likely you think of it as a business development and networking opportunity. You probably don’t consider a training course to be marketing. It’s more likely you think of it as editorial education. You probably don’t consider reading a book about the craft of writing to be marketing. It’s more likely you consider it knowledge acquisition. So how about this?

Training, embedding knowledge, writing essays, publishing research, sharing subject knowledge. Smashing stuff. Nicely done. And between you and me, it’s great content marketing too. But, shh, let’s keep that quiet. I know you don’t like marketing. Make your marketing about your editing If you don’t like marketing, maybe that’s because the kind of marketing you’re doing isn’t likeable. In that case, think about what you do like about running your business, and make those things the pivot for your marketing. [Click to tweet] In other words, it doesn’t need to be about choosing between marketing your editing business and learning to be a better editor, but about the former being a consequence of the latter. Two birds. One stone. Me? I’m off to read the latest Poirot. Just for fun, mind you!

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Are you using free indirect speech in your writing? This article provides an overview of what it is and how it can spice up crime fiction.

What is free indirect speech?

In a nutshell, free indirect speech offers the essence of first-person dialogue or thought but through a third-person viewpoint. The character’s voice takes the lead, but without the clutter of speech marks, speech tags, italic, or other devices to indicate who’s thinking or saying what. It’s a useful tool to have in your sentence-level toolbox because:

The table below shows three contrasting third-person narrative styles in action so you can see how free indirect speech works:

It’s also referred to as free indirect style and free indirect discourse.

1. Flexibility and interest Free indirect speech (FIS) is flexible because it can be blended seamlessly with other third-person narrative styles. Let’s say you want to convey information about a character’s physical description, their experiences, and their thoughts – what they think and delivered in the way they’d say it. You could use third-person objective for the description, third-person limited for the experience, and free indirect speech for some of the thought processes. In other words, you have a single narrative viewpoint but styled in different ways. You’re not changing the viewpoint, but rather shifting the distance between the reader and the character. And that can make your prose more interesting. Here’s an example from Val McDermid’s Insidious Intent (p. 14). She begins with a more distant third-person narrator who reports what had been on Elinor Blessing’s mind, and when. Then she shifts to free indirect speech (the bold text). This gives us temporary access to Blessing’s innermost thoughts – her irritation – and her lightly sweary tone, but still in the third-person:

Philip Prowse employs a similar shift in Hellyer’s Trip (p. 194): 2. A leaner narrative FIS is a useful tool when you want to declutter. Direct speech and thoughts are often tagged so that the reader knows who’s speaking/thinking:

With regard to thoughts, there’s nothing wrong with a reader being told that a character thought this or wondered that, but tagging can be interruptive and render your prose overworked and laboured if that’s the only device you use. Imagine your viewpoint character’s in a tight spot – a fight scene with an arch enemy. The pace of the action is lightning quick and you want that to be reflected in how your viewpoint character experiences the scene. FIS enables you to ditch the tags, focus on what’s going on in the character’s head, and maintain a cracking pace. The opening chapter of Stephen Lloyd Jones’s The Silenced contains numerous examples of free indirect speech dotted about. Mallory is being hunted by the bad guys. She’s already disarmed one in a violent confrontation and fears more are on the way. Jones keeps the tension high by splintering descriptions of step-by-step action with free-indirect-styled insights into his protagonist’s deepest thought processes as, ridden with terror, she tries to find a way out of her predicament:

Here’s an excerpt from Lee Child’s The Hard Way (p. 64). Child doesn’t use FIS to close the narrative distance. Instead, he opts to shift into first-person thoughts. Reacher is wondering if he’s been made, and whether it matters:

Some might argue that this is a little clunkier than going down the FIS route, but perhaps he wanted to retain a sense of Reacher’s clinical, military-style dissection of the problem in hand. If Child had elected to use FIS, it might have looked like this: Had they seen him? Of course they had. Close to certainty. The mugger saw him – that’s for damn sure. And those other guys were smarter than any mugger. [...] But had they been worried? No, they’d seen a professional opportunity. That’s all. It’s a good reminder that choice of narrative style isn’t about right or wrong but about intention – what works for your writing and your character in a particular situation. 3. Deeper insight into characters A third-person narrator is the bridge between the character and the reader. As such, it has its own voice. If there’s more than one viewpoint character in your novel, we can learn what we need to know via a narrator but the voice will not be the same as when the characters are speaking in the first person. FIS allows the reader to stay in third-person but access a character’s intimate world view and their voice. It closes the distance between the reader and the character because the bridging narrator is pushed to the side, but only temporarily. That temporary pushing-aside means the writer isn’t bound to the character’s voice, state of mind and internal processing. When the narrator takes up its role once more, the reader takes a step back. Furthermore, there might be times when we need to hear that character’s voice but the spoken word would seem unnatural:

FIS therefore allows a character to speak without speech – a silent voice, if you like. Think about transgressor narratives in particular. If you want to give your readers intimate insights into a perpetrator’s pathology and motivations, but are writing in the third-person, FIS could be just the ticket. Here’s an example from Harlan Coben’s Stay Close (chapter 25). Ken and his partner Barbie are a murderous couple bound together by sadism and psychopathy. Ken is preparing for the capture and torture of a police officer whom he believes is a threat:

This excerpt is from an audiobook. While listening, I could hear how the voice artist, Nick Landrum, used pitch to shift narrative distance. The book’s entire narrative is in the third-person, but Landrum used a higher pitch when presenting the narrator voice. Ken’s dialogue, however, is in a lower pitch, and so is the free indirect speech of this character – we get to hear the essence of Ken even when he’s not speaking out loud. If you’re considering turning your novel into an audiobook, FIS could enrich the emotionality of the telling, and the connection with your listener. A closer look at narrative distance To decide whether to play with free indirect speech, consider narrative distance and the impact it can have on a scene. Look at these short paragraphs, all of which convey the same information. All are grammatically correct but the reader’s experience is different because of the way in which the information is given, and by whom.

Your choice will depend on your intention. Think about your character, their personality, the situation they’re in, which emotions they’re experiencing, and the degree to which you want your reader to intimately connect with them.

Consider the following examples in relation to the table above:

Wrapping up FIS is used across genres, but I think it’s a particularly effective tool in crime writing because of its ability to simultaneously embrace brevity and communicate intimacy. Jon Gingerich sums up as follows: ‘Free Indirect Discourse takes advantage of the biggest asset a first-person P.O.V. has (access) and combines it with the single best benefit of a third-person narrative (reliability). It allows the narrator to dig deep into a character’s thoughts and emotions without being permanently tied to that person’s P.O.V. Done correctly, it can offer the best of both worlds.’ If you haven’t yet played with it, give it a go, especially if you’re looking for ways to trim the fat. Further reading

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

This article shows you what it might cost to get your novel line edited, copyedited or proofread. However, the short answer is: it depends ...

This post headlined in Joel Friedlander's Carnival of the Indies #94

I’ll look at each of these points in turn, then offer you some ideas of what you can do to reduce the financial hit.

First of all though, a quick word on whether you should bother and, if you do, what type of service you should invest in. Do you have to work with a professional editor? Not at all – it’s your choice. That’s one of the biggest benefits of self-publishing. You get to stay in control and decide where to invest your book budget. However, I absolutely recommend that your book is edited ... by you at the very least, but ideally by a fresh set of eyes, and even more ideally by a set of eyes belonging to someone who knows what to look out for. And the reason for that recommendation is because 99.99% of the time, editing will make a book better. We can all dream about first-draft perfection, but it’s pie in the sky for most, even those who edit for a living. I’m a professional line editor, copyeditor and proofreader, and today I wrote a guest blog post for a writer. I wrote, and then I edited ... first for content, then for flow, then for errors. I found problems with each pass. That’s not because I can’t write. It’s not because I can’t string a sentence together. It’s not because I didn’t edit properly in the first round. The reason I found problems is because writing is one process – editing is another:

And the different types of editing attend to different kinds of problems and have different outcomes. Trying to do everything at once is like trying to mix a cake, bake it, ice it, eat it, and sweep up the crumbs all at the same time. Breaking down the writing and editing processes into stages is a lot less messy, and the quality of outcomes is much higher. Still, that has a cost to it, and it’s a cost that the self-publisher will have to bear because there’s no big-name press to bear the burden for them.

Cost of editing: the individual editor

The independent editing market is global and diverse. Editors specialize in carrying out different types of editing. Some specialize by subject or genre. They have different business models and varied costs of living. And that means that despite what you might read in this or that survey, there is no single, universal rate. Neither is there a universal way of offering that rate:

My preference is to charge on a per-word basis, subject to seeing a sample of the novel. Because economies of scale come into play with longer projects, my per-word prices decrease as the project length increases. For example, in 2020, I charge 7.5 pence per word for a 1,000-word sample edit, but the fee is 20% cheaper if I'm line editing a 5,000-word story and 50–60% cheaper if I'm dealing with an 80,000-word novel. And so it depends on the parameters of the project. Some editors charge more than me, some less, and some the same. My colleagues live all over the world, and fluctuations in the currency-exchange markets mean that comparisons will yield different results from day to day.

Cost of editing: industry surveys and reports

Some professional organizations suggest or report minimum hourly rates for the various levels of editing. They’re ballparks, nothing more, for reasons outlined below the table (fees correct as of July 2019).

ARE THESE RATES REALISTIC?

Do these figures bear any relation to what individual editors charge? Sometimes but not always. Most organizations recognize that these reported prices don’t always reflect market conditions, and they’re right to do so. Many editors and proofreaders, myself included, aim for rates at least 30% higher. Why? Because that’s what it takes for our businesses to be profitable. Editing and proofreading aren’t activities we do in our spare time. They're not side hustles. They’re careers that enable us to pay the bills. If we can’t meet our living costs, we become insolvent, just like any other business owner. The problem with these ballparks is that they don’t reflect the speed at which an individual works, the complexity of each job, the time frame requested, or the editor’s circumstances. An additional problem is that how these organizations define ‘proofreading’, ‘copyediting’ etc. might not reflect an author’s understanding of what the service involves, or what an editor has elected to include. And then there’s the age-old issue of currency-exchange rates. What might seem a high rate to you one day could turn into something quite different the next, and not because the editor’s or the author’s life has changed, but because of Trump, or the Bank of England, or a hung parliament here, or a banking crisis there. Bear in mind that independent editors are professional business owners, and just like any other business owner they are responsible for tax, insurance, sick pay, holiday pay, maternity/paternity entitlements, training and continued professional development, equipment, accounting, promotion, travelling expenses, pension provision, and other business overheads.

Cost of editing: turnaround time

The table below gives you a rough idea of the speed at which an editor can work. Again, we’re dealing with ballpark ranges because the true speed will depend on the complexity of the project and how many hours a day the editor works.

Experienced editors have years’ worth of data that enables them to review a sample of a novel and estimate how long a project will take based on the level of editing requested.

The figures in the table above represent a working day of around 5 hours of actual editing. Additional time will be spent on business administration, marketing and training. Here’s how costs might begin to creep up. Imagine you ask your editor to copyedit your 80K-word novel. The editor estimates the job will take 50 hours, or two weeks. You need it in one. If you want to work with that editor, they’re going to have to work 10 hours a day, not 5. That means they have to pull 5 evenings on the trot in addition to their standard working day. That evening work is when they spend time with their families, recharge their batteries, catch up with friends, support their dependents, carry out the weekly food shop, help their kids with the homework ... normal stuff that lots of people do. If you want them to work during that time, it’s probably going to cost you more. For example, I charge triple my standard rate because my personal time is valuable to me – and to my child, who will need bribing!

Cost of editing: the complexity of the project

The more the editor has to do, the longer the job will take and the higher the cost. Some authors might not be aware of the different levels of editing and what each comprises. And editors don’t help – we define our services variously too! For that reason, sometimes it makes sense to move away from the tangled terminology and focus on what each project needs to move it forward. An author might ask for a ‘proofread’ but the editor’s evaluation of the sample could indicate that a deeper level of intervention will be needed ... something more than a prepublication tidy-up. I’ve copyedited novels whose authors had nailed narrative point of view at developmental editing stage, so I didn’t have to fix the problem. I’ve also copyedited novels in which POV had become confused. The sample-chapter evaluation highlighted the problem, and I had to adjust my fee to account for the additional complexity.

How to reduce your editing costs

So, there we have it – 1,300 words that tell you not what editing and proofreading will cost, but what they might cost, depending on this, that, and everything else! Here are some ideas for how to reduce your costs. GENERAL MONEY-SAVING TIPS

SAVING MONEY ON DEVELOPMENTAL EDITING Hone your story craft by reading books, taking writing courses, and joining writing groups through which you’ll be able to access fellow scribes! You can critique each other’s work and help each other with self-editing. I recommend these books:

Rather than commissioning a full developmental edit, you could pay for a critique or manuscript evaluation, or a mini edit. Those will help you to identify what works and what doesn’t so that you can make the adjustments yourself. SAVING MONEY ON LINE EDITING Hone your sentence-level mastery, again through books, courses and groups. Some editors offer mini line edits for this stage of editing too. Here, the editor offers a line-by-line edit on several chapters and creates a report on the sentence-level problems with the text with recommendations for fixing them. The author can then refer to the mini line edit and mimic the sentence smoothing and tightening. This kind of service is particularly useful for beginner authors who already know they’re prone to overwriting. And I have a book you might find useful:

SAVING MONEY ON COPYEDITING Learn how to use Word’s amazing onboard functionality, and macros and add-ins that flag up potential errors and inconsistencies. Here are some tools you can use:

SAVING MONEY ON PROOFREADING If you’re working on designed page proofs, there are a series of checks you can take your novel through.

That’s it! I hope this article has given you a sense of what you might have to spend, and how you might be able to save during the editing process.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses. |

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed