|

Proofreading doesn't mean the same thing to everyone. Editorial terminology can get proofreaders and their clients in a tangle! Avoid making assumptions, and focus instead on what the client wants and needs.

I trained as a proofreader in 2005. For more than a decade beforehand I’d worked in a professional publishing environment, specifically in the marketing department of two mainstream academic publishing houses with an international presence. I knew exactly what proofreading was, and what it wasn’t — or I thought I did!

Only a few months into professional practice, my understanding of the skill set I’d chosen to specialize in was challenged. To this day, it is still being repeatedly challenged. Publishers’ expectations of what a proofread entails match my training and in-house experience, but students, schools, charities, businesses, and beginner-novelists often have very different ideas. The term proofreading, far from being straightforward, now appears rather more complicated. Indeed, how one defines proofreading isn’t determined by what one actually does, but rather by whom one talks to.

Industry definitions — what a proofreader does

National editorial societies tend towards offering definitions of proofreading that accord with publishers’ expectations. This is not surprising given that publishers provide thousands of professional proofreaders with regular work. If you want to be fit to proofread for this client type, you need to understand what this client type’s expectations are. You no doubt want the professional body that represent you to provide guidance that reflects industry-recognized best practice. Below I've quoted excerpts from several national editorial societies’ online definitions of professional proofreading.

Editors’ Association of Canada (Canada): 'Definitions of Editorial Skills'

'Examining material after layout or in its final format to correct errors in textual and visual elements. The material may be read in isolation or against a previous version. It includes checking for:

Society for Editors and Proofreaders (UK): 'What is proofreading?'

'After material has been copyedited, the publisher sends it to a designer or typesetter. Their work is then displayed or printed, and that is the proof – proof that it is ready for publication. Proofreading is the quality check and tidy-up. However, some clients expect more than that.Many proofreaders find they spot more errors on paper than on screen, but proofs may be read and marked in either medium. Proofreading is now often 'blind' – the proof is read on its own merits, without seeing the edited version. A proofreader looks for consistency in usage and presentation, and accuracy in text, images and layout, but cannot be responsible for the author's or copyeditor's work. The proofreader's terms of reference should be agreed before work starts.'

Association of Freelance Editors, Proofreaders & Indexers (Ireland): 'What do proofreaders, editors and indexers do?'

'The proofreader reads page proofs after edited copy comes back from the typesetter or desk-top designer. The proofreader’s job is to make sure that text, illustrations, captions, headings, etc., are properly placed and complete; to check that design specifications have been followed; to check running heads; to ensure that captions and legends match artwork; to ensure that pagination matches the Contents list; to check end-of-line breaks; to proofread preliminary pages and end matter (e.g., the index if there is one); to fix incontestable errors of spelling, punctuation and grammar that have slipped through the net during copy-editing; and to query inconsistencies.'

Institute of Professional Editors (IPEd) (Australia): 'Levels of editing'

'Proofreading (usually called this but sometimes known as verification editing) involves checking that the document is ready to be published. It includes making sure that all elements of the document are included and in the proper order, all amendments have been inserted, the house or other set style has been followed, and all spelling or punctuation errors have been deleted.' These excerpts reflect very well the tasks required by the publishers and project-management agencies that procure professional proofreading services. The emphasis is on the expectation that the proofreader will not be amending raw text, but will be annotating proof pages, post design, either in print or in digital format, usually using industry-recognized markup language. When it comes to working for publishers, the notion of 'proofreading' is not tangled. Things start to get a little messy, however, when we branch out into the wider world. Non-publishing clients – what a proofreader might do Some national editorial societies recognize that definitions of proofreading start to tangle when the proofreader’s client base extends beyond the publishing industry. See for example, the SfEP's 'What is proof-editing?' for a brief but useful introduction to how a proofreader may be asked to work with raw text and intervene in a way that the publishing industry would define as light copy-editing (or another skill set). Below are some excerpts of requests from non-publishing clients that I’ve received. I’ve tweaked these so that the original request is masked. The point is to give you a flavour of how some non-publishing clients interpret the term.

Proofreading a novel

'I have a 95,000-word novel that needs proofreading. I've been through it several times myself but it needs professional eyes on it before I publish. A beta reader told me there are some viewpoint problems, that my pacing is off and that the characters need developing. Hoping you can help.' Proofreading letters 'Please provide me with a quotation to proofread a 150,000-word book in MS Word. The text is not always grammatical because of the way the letters were written, and I would like such instances to be left as is. I am looking for nonsensical errors etc. and general comments on layout and structure and sequencing.' Proofreading a novella 'Would you be kind enough to advise me of the cost of proofreading my science-fiction novella (32,000 words)? I can provide the file in Word format. English is my second language. I need attention to spelling and grammar, and altering any words that don’t sound quite right to an English speaker’s ear. I’d also like it formatted so that I can upload it to Amazon.' Proofreading a Master’s dissertation 'I urgently need the first draft of my dissertation to be proofread. I need it styled in British English and would like it cut down if possible.' Proofreading a website 'A new section of our site needs proofreading, approximately 15–20 pages totalling 5,000 words. We would provide you with access to the site and then you can simply go through each page and edit it directly.' All of the above clients want the 'proofreader' to edit the raw text directly. However, they also require a range of other tasks that, traditionally, fall well outside the proofreader’s remit — structural decisions, rewriting, text reduction, and layout and text styling. And, in the final case, the proofreader would be required to directly amend the text within a content management system. There's nothing wrong at all with an editor carrying out these tasks as long as the they feel competent to do so, and as long as the client and the editor have a mutual understanding of what can/can’t or will/won’t be done as part of the project. The point is, rather, that these tasks would be far less likely to be requested in a proofreading brief from a publisher. This is the tangled world of proofreading.

'But that’s not proofreading'

Yes, the extra-proofreading requirements identified above – amending raw text, taking structural decisions, rewriting, reducing the amount of content, layout and text styling tasks, and working directly in content management systems – are certainly not how many professional proofreaders would define proofreading. However, as business owners, we’re required to communicate with our clients in a way that makes them believe we can solve their problems. If I want to take on a proofreading commission that also involves styling the text in the Word file of an indie author’s book so that it’s ready for upload to Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing program, and I have the skill to do this, I’m not going to engage the client in a discussion over semantics. If I want the job, and I can do the job, I’ll quote for the job. If the client wants to call it proofreading, we’ll call it proofreading. In the non-publishing world, definitions of proofreading are tangled, but I know this. What’s important is not that I quibble over the definition, but that I unpick the client’s request so that we are both clear about what is required.

Marketing your proofreading business in a way that clients understand

There’s a reason I don’t offer 'proof-editing' services, even though that’s exactly what some independent authors want. It’s because they won’t find me. The analytics data for my website, tells me that people are landing on my website after typing in the word proofreader, not proof-editor or proof-editing. Definitions of proofreading might appear tangled to those of us within the editorial and publishing industries, but to many non-publishing types things are rather less messy!

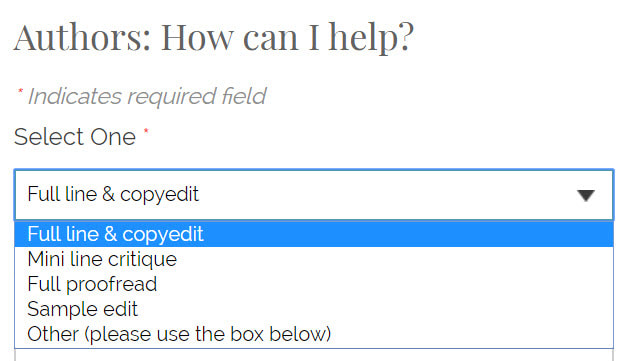

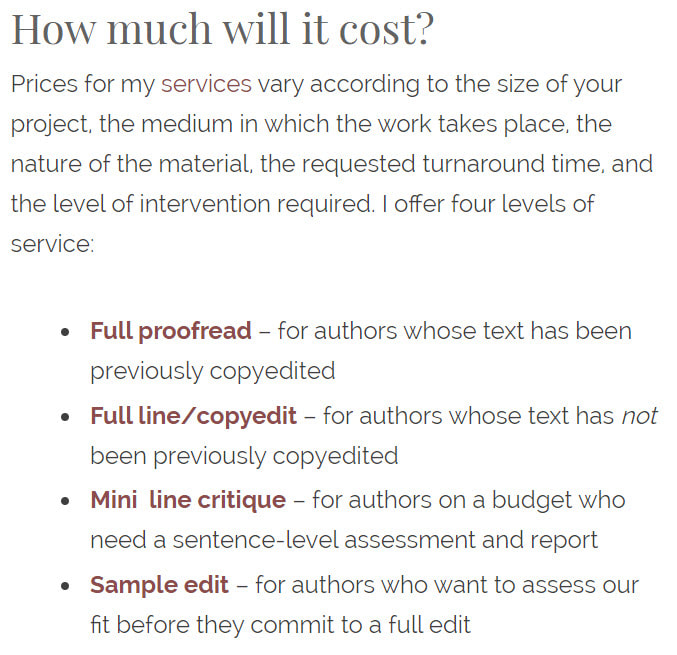

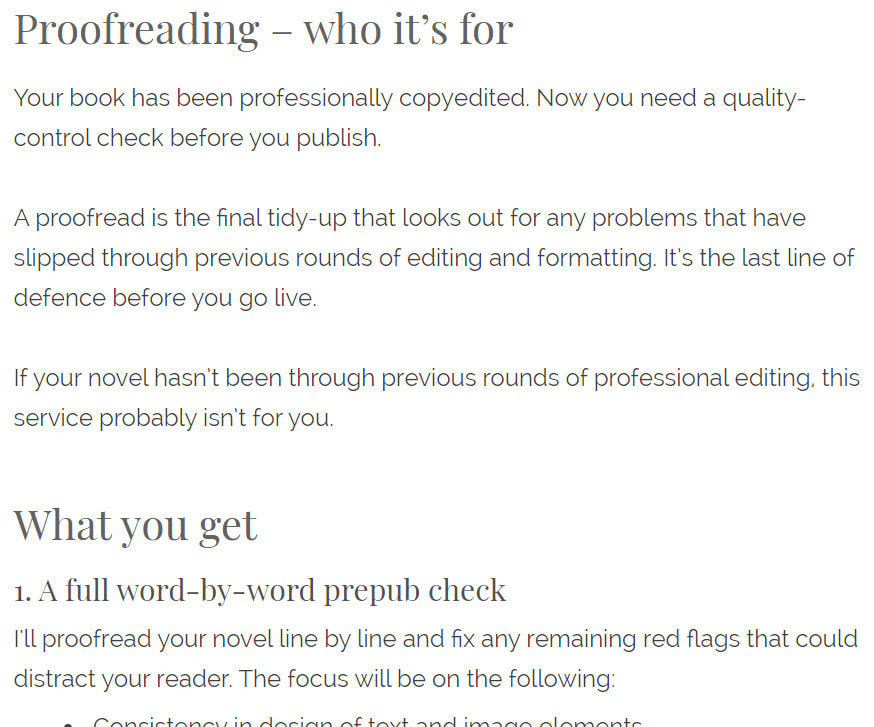

Sometimes we can help. Sometimes we can’t. How far any editor is prepared to step outside of traditional publishing-industry definitions of proofreading will depend on preferences, skills, experience, and level of confidence. Nor does that mean an editor has to stop calling themselves a proofreader or saying they offer proofreading services, especially if calling themselves a proofreader is what makes them discoverable to their clients. Providing clear service definitions Here's one way to ensure there's a shared understanding of the term proofreading: clarify your service offerings. Think about which pages your potential clients use to discover more about what you do and how to get in touch with you. Those are where you can help them navigate your website and access the information that explains how you define proofreading. Here's how I do it. There are 6 alerts about the levels of editing I offer (of which proofreading is one) and how I define them.

If you receive requests for proofreading but the samples often indicate that a different level of editing is required, think about how you might add clarity so that clients better understand what you offer – and what they need – before they get in touch.

Summing up If you want to be a proofreader, don’t assume there’s only one set of client expectations about what you will or won’t do, or what proofreading is or isn’t. In an international marketplace made up of numerous different clients with widely varying problems, you’ll always be required to spot spelling errors and incorrect punctuation. But there’s a raft of other tasks that you could be asked to undertake, too. Whether you accept the challenge will depend on what you are prepared and able to do, not what you call yourself. Whatever you call what you're offering, take care to charge accordingly. If that 'proofread' is more akin to a line- or copyedit, it needs to be priced in a way that reflects the additional work being carried out.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with independent authors of commercial fiction, particularly crime, thriller and mystery writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Society for Editors and Proofreaders (SfEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn.

2 Comments

If you're a writer or editor who says, "That's not a word!", then this useful link might make you reconsider: OneLook Dictionary Search. (Hat tip to Stan Carey on the Sentence First blog for drawing my attention to it.) Simply search for your chosen not-a-word and OneLook will provide you with a list of links to dictionaries that provide definitions according to current usage. Of course, that doesn't mean you have to like the word that you think is not a word but that actually is a word. Nor does it mean you have to use it. But not liking or not using a word is not the same thing as denying its existence! The following make for interesting and often entertaining reading (the sometimes passionate comments attached to these posts are worth taking a look at, too):

Louise Harnby is a professional proofreader and copyeditor. She curates The Proofreader's Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. Someone recently emailed me to ask my advice about returning to the world of editorial freelancing after a break. In particular, they wanted to know whether free courses were worthwhile, and, if so, which one they should take. My answer was that the issue of free versus paid missed the point. Rather, it depends on what is required by the individual. If your skills are sound with the exception of one particular gap in your knowledge, e.g. how to use proofreading markup symbols, and you find a free course that teaches this, then it’s going to be a great course for you, one that's worth doing despite the fact that it costs nothing but your time. If, however, you need a comprehensive tutor-based course that teaches you how to use markup language, make sensible decisions about when to mark up and when to leave well enough alone, how to work with paper and onscreen files, and provide you with a solid grounding in how publishing and production processes work (and your place within them), then this free course, which only teaches you how to use markup language, will be next to useless. Of course, we all have budgets. I love a freebie as much as the next person and I've taken advantage of several free or low-cost tutoring programmes over the years. I've also forked out hundreds of pounds in the process of learning new skills. Which of those courses were the most worthwhile? The freebies or the bank-account drainers? The answer is, all of them. That's because I picked the courses that I felt would teach me what I needed to know. When training for professional business practice, the primary indicator of whether the training is worthwhile is not the price; rather, it is the degree to which the course content fills our knowledge gaps. 3 fictive case studies Jenny is a social worker from Dublin who is thinking about transitioning to freelance proofreading. She has no previous editorial experience, though her academic and career credentials are outstanding. As I said, she's thinking about transitioning – she hasn’t yet made up her mind whether this is the right move. She contacts the Association of Freelance Editors, Proofreaders & Indexers (AFEPI), Ireland’s national editorial society. One of the joint-chairpersons tells her that the society is running a half-day “introduction to proofreading” session. The course is a bargain at only 40 euros. She also finds a free online proofreading course that takes about an hour to complete. Are these worth doing? In Jenny’s case, they are excellent opportunities that will give her a taste of what professional proofreading involves but won't require her to invest large amounts of her hard-earned cash before she's made up her mind about her future career steps. Will they make her ready to hit the ground running in the world of professional proofreading practice? No, but that's not what she needs at the moment. Dan is former experienced and highly recommended copyeditor and proofreader from Toronto. He put his career on hold while he took on the full-time care of his partner, who'd been diagnosed with a long-term illness. Dan’s been out of the editorial freelancing world for 15 years and is now ready to re-enter the marketplace. He's no newbie but he does feel very rusty. The editorial environment has changed somewhat in the past decade and a half. More work is being done digitally than was the case when he was previously in practice, so his tech skills are out of date. His research enables him to identify the gaps in his technical knowledge. He's located a series of free online tutorials that will enable him to develop these tech skills. Dan is also concerned that because he hasn’t worked on professional material for a long time he's forgotten some of the foundational principles that underpin his practice. He decides that full Editors’ Association of Canada (EAC) certification in copyediting and proofreading might be overkill at this point. However, the Toronto branch of the EAC runs a number of brush-up seminars that will be useful to him. In addition, the EAC offers two relevant study guides for a total cost of just over CAN$100. Price-wise, the investment is not insignificant by any means, but he thinks that the curriculum covered will bring his knowledge up to date. Later, he may use this study programme to become certified. Mati is a successful London-based professional English/Italian translator. She wants to extend her service portfolio to include proofreading. In addition to working with independent authors and academics, she wishes to proofread for publishers. She decides to source an industry-recognized and comprehensive course that will train her to professional standards. She's short on money because her London flat costs her a fortune each month. She's identified a number of free online proofreading programmes, and a couple of books dedicated to the subject. None of them offer her the depth of content that she feels will give her the confidence to enter professional proofreading practice; plus, she’d really like to have a tutor for mentoring purposes. The course she thinks will be perfect for her is the run by the Publishing Training Centre (PTC) but it costs £395. The free course options or the books will solve her financial issues, but they won't give her the detail or the mentoring. The PTC option will give her the detail and the mentoring but will leave her unable to pay next month's rent. She decides to save up for the PTC course over six months. In the meantime, she continues to focus on her translation work, and uses the time she’d set aside for the PTC proofreading course to develop a marketing strategy aimed at building a proofreading client base that will complement her existing translation-client work. Curriculum before cost ... Free or cheap can be superb or it can be useless. Expensive can be comprehensive or overkill. That's because the cost of the course is not the right indicator. Rather, the content of the course, and the degree to which that content addresses a particular skill gap, is what counts. Certainly we must not ignore free or low-cost tutorials, webinars, books, courses and conferences – if they teach us what we need to know they'll be a boon for our business development. On the flip side, we shouldn’t dismiss training that we consider to be expensive if that training is what will enable us to compete in the editorial freelancing market effectively. When we find that the training we need costs more than we can currently afford, we need to develop a plan to finance that training. If I can’t afford the course that I’ve identified as the one that will fill the gaps in my professional knowledge, I might decide to save up for it, just as Mati did. Imagine that your child’s nursery teacher, your electrician or your dentist told you they couldn’t afford to do the training they'd identified as making them fit for purpose and so they’d opted not to bother, instead turning to cheaper or free courses that only taught them a few of the things they needed to know. Would you let them near your kid, your fuse box or your mouth? Our clients are no different. They want us to be fit for purpose. Curriculum is always the primary indicator that we should focus on when evaluating how worthwhile a training course is. Using content as the basis of selection will drive us into a position where we acquire the skills we need to solve our clients’ problems such that they will hire us repeatedly and recommend us to their colleagues. Some of that content will be free, some of it will cost a pretty penny, and some of it will sit somewhere in between those two extremes. Take your pick but base your choice on what you need to learn, not on what you'd like to pay. If you want advice on the editorial training that's most appropriate to your circumstances, talk to the training director of your national editorial society. Most associations offer a range of learning opportunities within different environments to suit people's varying needs, skills and levels of experience. Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers. She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses. |

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed