|

A vocative expression is one in which a person is directly referred to in dialogue. It needn’t be someone’s name; it could be a form of address that relates to their job or position, or a term of endearment, respect or disrespect. Here’s how to work with them.

Purpose of vocative expressions

Vocatives serve several purposes in fiction writing: 1. They help readers keep track of who’s saying what to whom. This is especially useful when a character is talking to two or more people.

‘Dan, can you take the father into Interview Room 2? I don’t want him having to face the mother – not yet, anyway.’ Charlie flicked through the file and scanned down the penultimate page. ‘Deputy Douglas, I know you’re new to the team but I’d like you to handle the mom.’

2. They can enrich characters’ emotions by conveying a deeper sense of urgency, frustration, surprise or patience. 3. Readers can learn quickly about how characters relate to each other. Does one rank higher or defer to the other? Perhaps they’re friends, lovers, or loathe each other.

Overuse that distracts Overusing people’s names and titles can be grating. Vocatives aren’t the only way of signalling who’s being talked to – you could use action beats (See: What are action beats and how can you use them in fiction writing?). And if there are only two people in a scene it will be unnecessary to continually use direct forms of address. Think about the natural speech you hear in your everyday life. Most of the time, people don’t use vocative expressions excessively. Follow their lead in your novel. Compare the following examples:

The original version is much cleaner. The vocative in the first line helps to convey Vivian’s sarcasm. After that, Chandler lets us do the work and the conversation sounds natural. How to punctuate vocatives Commas are required for clarity.

Punctuating vocative expressions incorrectly can lead to ambiguity. Compare the following examples of dialogue. Notice how the missing comma changes the meaning from expressions of address to instructions to carry out acts of violence.

Lower-case or upper-case initials?

Should you use lower-case or upper-case initials when addressing a person in written dialogue? It depends. People’s names Names are proper nouns and therefore always take initial capital letters in the vocative case.

“What the hell are you doing with that novel, Louise? You’ve changed how all the vocative expressions are punctuated,” said Johnny.

‘You, Ringo, are a cad and a bounder. However, I’m prepared to forgive you because of your excellent taste in music,’ said George, thumbing through five different editions of The White Album. Terms of respect, endearment and abuse Vocative terms of respect and endearment take lower case when used generally. Examples include: madam, sir, m’lady, miss, milord, mister; buddy, sweetie, darling, love, dear; and dopehead, fuckwit and plenty more I’d love to write here but won’t!

When terms of respect are used in conjunction with names, they become proper nouns and take upper case. Endearments and insults usually remain in lower case because they’re used adjectivally.

Titles of rank and nobility Titles of rank and nobility take initial capitals when used vocatively. Examples include: Your Majesty, Commander, Constable, Agent, Lord, and Detective Inspector. Compare these with narrative text and dialogue that include indirect address forms. If the relational titles are used as names (proper nouns), we retain upper case. If we’re using common nouns with determiners (a modifying word that references a noun such as ‘a’, ‘the’, ‘each’, ‘her’ and ‘my’) we use lower case.

The commander knocked on the door and marched in without waiting for an invitation.

Fifteen minutes later, the chief called the squad into the incident room. ‘I’ve asked Inspector Harnby to take a look at the case. Hope that’s okay with you.’ ‘That other constable is a waste of space, don’t you agree, Constable MacMillan?’ Titles indicating a relationship When used as a form of direct address, relational titles take upper case. Examples include: Mother, Uncle, Dad, Auntie, Grandma and Papa.

‘I’m begging you, Dad, don’t make me watch that Jimi Hendrix docudrama again. Thirty-five times is enough.’ I smashed the guitar over the back of the sofa and stuck my nose in the air. ‘See? It’s never going to happen.’

“Oh, don't refer him to me, Mama! I have just one word to say of the whole tribe – they are a nuisance.” (Jane Eyre, Chapter 17) Again, compare these with narrative text and dialogue that include indirect address forms. If the relational titles are used as names (proper nouns), we retain upper case. If we’re using common nouns with determiners, we use lower case.

I thought back to the earlier conversation. Hadn’t his dad said we could catch the 8.15 from Waterloo if we put our skates on?

‘Can you ask your uncle if we can stay at his place this weekend?’ ‘Every grandmother receives a free cup of tea and a slice of cake. Do you think Gran would like to come?’ The guy’s mom was an absolute monster, or so he’d heard. That was just one side of the story, though. Best to check before bowling in and arresting anyone. Summing up Use vocatives as follows:

And, thank you, dear reader, for getting to the end of this article! (See what I did there?) Cited sources

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

8 Comments

Powerful dialogue and thoughts enrich a story without the reader noticing. When done poorly they distract at best and bore at worst. Here are 8 problems to watch out for, and ideas about how to solve them.

Problem 1: Maid-and-butler dialogue

Is one of your characters telling another something they already know just so you can let your reader access backstory? If so, you’ve written maid-and-butler dialogue. It’s a literary misfire and should be avoided. Here's an extreme example:

‘Hi, Jenny! It’s good to see you after your three years at Nottingham University. Bet you’re delighted with that first-class honours degree in archaeology.’

‘Thanks. Yeah, I’m thrilled to bits, though there have been times when I’ve yearned for your nine-to-five job as an editor in a small fiction publishing company on the outskirts of Norwich.’ SOLUTIONS

‘Hi, Jenny! Good to see you. Been a while.’

Three years in fact. Clever Jen had notched up a first in archaeology from Nottingham Uni while I was inching my way up the publishing ladder with a small fiction press on the outskirts of Norwich. ‘Yup,’ she said. ‘Seems like an age. How’s tricks in the world of business? Found the next Booker Prize winner yet?’ Problem 2: Real but mundane The conversations many of us have in real life are deathly boring. Here’s one I had recently:

‘Fancy a brew?’

‘Yes, please. Coffee please. Er, or tea. Um, whatever you’re having. As long as it’s wet and warm.’ ‘I’m having coffee but I’m happy to make you tea.’ ‘No, erm, coffee’s perfect. Thanks.’ ‘Milk and sugar?’ ‘Just milk. No sugar, thanks.’ ‘Okay.’ ‘Cheers.’ ‘Um, can I use your bathroom?’ ‘Of course you can. There’s extra loo roll in the cabinet if you need it.’ It’s realistic, certainly, but has no place in a novel. Most of the words are a waste of space, and the trees that were felled to create the paper on which they’re written deserve better. Dialogue needs to be natural, but not too natural. The best dialogue is a hybrid of the real and the contrived, ‘a kind of stylised representation of speech’ as Nicola Morgan calls it in Write to be Published (p. 151). SOLUTIONS

Problem 3: Written accented dialogue It can be tempting to convey accents with phonetic spellings, as in these appalling examples below:

‘Zis cannot be ’appening. Zer family would sinc it unacczeptable.’

‘Ve have vays of getting vat ve vant.’ There are so many problems with this approach that I recommend you avoid it altogether. Bear in mind that dialogue tells us what words have been spoken, not how they’re spelled. Phonetic spelling can turn dialogue into pastiche, and offensive pastiche at that. It’s also difficult to absorb and distracts readers from your story. SOLUTIONS

Problem 4: Troublesome tags The function of speech tags is to tell the reader who’s speaking. They shouldn’t push the dialogue into the background. Nor should they repeat what the reader knows from the dialogue. Furthermore, the verbs we use to tag the dialogue should be speech-related. Otherwise we end up with a reality crash that jars the reader.

‘That dress looks ridiculous,’ guffawed Marie.

‘Come here. Let me show you how it works,’ demonstrated Jonathan. ‘I swear I’ll stick this knife where the sun doesn’t shine if you don’t give me the letter,’ brandished Marcus. SOLUTIONS

Problem 5: Talking heads and monologues Some books can turn into podcasts on the page when dialogue isn’t grounded in the physical environment. Too much dialogue can make the reader feel dissociated from the story, as if the characters are talking in the cloud. In Jo Nesbo’s The Bat, McCormack starts talking on p. 249. On p. 250, Nesbo introduces one line of movement: ‘He turned from the window and faced Harry.’ Then McCormack’s off again. He doesn’t stop talking until p. 251. It’s a monologue in which Hole, the viewpoint character, seems to be nothing more than a receptacle for McCormack’s ear bending. There’s a little bit of back and forth with Hole, plus some action beats in the lower third of p. 251, but then McCormack’s off again for all of p. 252 and the top third of p. 253. The blue highlights show how much of these four pages are taken up with just one character’s speech.

Perhaps it’s deliberate, a way of showing that McCormack’s feeling jaded, worn down by the business of policing. Plus, Jo Nesbo has a big enough fan base to get away with this. However, for the writer who’s building readership, lengthy passages of speech that aren’t grounded in their environment could turn into snooze-fests.

SOLUTIONS

Problem 6: ‘Too many vocatives, Louise.’ The vocative case enables the writer to indicate who’s being spoken to in dialogue. In a bid to avoid speech tagging, some less experienced writers overuse vocatives, which renders the speech unnatural. Next time you get the opportunity to listen to a conversation between two people, notice how often they use each other’s names. You might find they don’t, other than for emphasis. Overuse can labour dialogue, as this example illustrates:

‘Louise, did you murder the sheriff?’

‘I didn’t murder anyone, Johnny. And I’m gutted that you felt the need to even ask that question.’ ‘I’m sorry, Louise, but it’s standard procedure.’ ‘Johnny, you don’t really think I could’ve done that, do you? ‘Not for a second, Louise. Just playing by the rules.’ The exception is dialogue between ranking officers or titled people and their staff. Omitting the sir, Your Lordship, Your Majesty, milady and the like would be unrealistic:

‘Sergeant, how many arrests have been made?’

‘Twelve, sir. We’re expecting two more today.’ ‘Any news on the Merton Street lead?’ ‘Not yet, sir.’ ‘Keep me informed, will you?’ ‘Yes, sir.’ SOLUTIONS

Problem 7: Thoughts in speech marks Speech marks (or quotation marks) have one function – to show the reader that a character is speaking out loud. While some recognized style guides allow for the use of speech marks to indicate thoughts, most professional editors and experienced writers don’t recommend this method because it’s confusing. Some authors might be tempted to use a different speech-mark style to indicate a thought. Again, this is confusing. Your reader might assume that you’ve not edited for consistency. Here’s an example in which dialogue and thought have become muddled:

“Jackson, put that gun down. You’ll hurt someone.”

“No way. Not until I have some guarantees.” Jackson gripped the weapon and glanced left then right. He was surrounded by agents, all of them armed to the teeth. ‘Fuck fuck fuck. How the hell am I going to get out of this one?’ he thought. SOLUTIONS

Problem 8: Thinking unlikely thoughts If your character’s in the middle of an escape, a heist, great sex, or a mixed-martial arts smackdown, thoughts need to be handled with care to remain realistic. High-intensity scenes require rapid-fire thoughts otherwise the thinking becomes intrusive and moderates the pace of the action. Here’s an extreme example of how things can go awry:

Fleur dove behind the chair as the wall exploded. She fumbled for the phone, choking on brick dust, and punched a number onto the screen. Pick up, dammit. God, what I wouldn’t give for a hot bath, a long gin and a warm fire. I haven’t taken time off in ages – not since last summer when I went to the Lakes for a couple of weeks. When this is over and done with, I’m going to hunker down and chill for a few months … just me, the dog and a sandy beach.

Gunfire sent her scrambling on her belly for the door. Some writers use a character’s thoughts as a conduit for providing physical description. Take care with this. In reality, it’s rare for us to look in a mirror and notice our brown hair, green eyes or big feet. Instead, we’re more likely to frame those ideas in terms of criticism, appreciation or concern: Compare these two examples:

SOLUTIONS

Summing up ‘Dialogue isn’t a report of everything that characters say. It’s the compelling and noteworthy real-time, purpose-filled talk that plays out in front of the reader,’ writes Beth Hill (p. 157): The same can be said of thoughts. Reality takes a nosedive when it comes to the novel because only a little of what people think and say in real life will drive a story forward. Most of it is dull. Here’s Sol Stein (p. 113): ‘People won’t buy your novel to hear idiot talk. They get that free from relatives, friends, and at the supermarket. […] Some writers make the mistake of thinking that dialogue is overheard. Wrong! Dialogue is invented and the writer is the inventor.’ Invent dialogue and thoughts that show readers what is being felt (emotion) and what is happening (action). Cited sources and other resources

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

If you’re including fingerprint science in your fiction writing, these tips will help you get the basics right.

Fingerprints are an established part of forensic procedure. If they’re in your novel, you’ll need to think about the science, the degree to which you’ll stay true to reality, and how much detail to include without turning your fiction into a textbook.

Here are 9 tips to get you started. 1. Know how a fingerprint is formed In ‘Introduction to Forensic Science’, Penny Haddrill describes fingerprints as follows:

‘On our fingers and toes there are many fine ridges. These ridges form recognisable patterns and are formed during the gestation period of the foetus during pregnancy. Fingerprints are produced from the contact between the ridges present on our fingers and a surface. The transfer is achieved by the deposition of the secretions from our glands associated with the ridges on our skin or by contaminants present on the finger surface.’

2. Know your terminology If you’re seeking authenticity, the terminology you use will be determined by where your novel’s investigators are based. If your fiction is set in the UK at least, ‘fingerprint’ and ‘fingermark’ mean different things:

3. Categorize your fingermarks correctly In Explore Forensics, Jack Claridge offers three categories of mark (though, again, in your novel’s jurisdiction, these might be referred to as prints):

4. Understand where the science wobbles It is believed that no two fingerprints are alike but there is no empirical evidence to prove this. While it’s true that, to date, identical fingerprint matches have not been found, there are enough similar ‘matching points’ between two people’s prints such that false positives and negatives have occurred. Says Laura Spinney in Nature:

‘Fingerprint analysis is fundamentally subjective. Examiners often have to work with incomplete or distorted prints — where a finger slid across a surface, for example — and they have to select the relevant features from what is available. What is judged relevant therefore changes from case to case and examiner to examiner.'

You might want to bear this in mind when your characters are doing or talking about fingerprint uniqueness. 5. Get the twin stuff right Identical twins have almost identical DNA because they develop from one zygote (created by one egg and one sperm) that splits into two embryos. Fingerprints, however, are formed during foetal development. Here's Spinney again:

‘The ridges and furrows on any given fingertip develop in the womb, [and are] shaped by such a complex combination of genetic and environmental factors that not even identical twins share prints.’

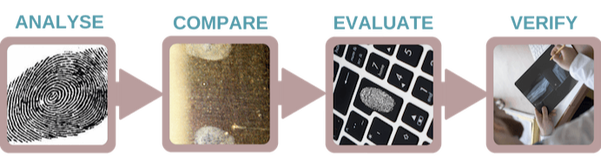

With that in mind, don’t make the mistake of hanging your plot on murderous monozygotic mayhem created by a couple of trickster twins. Their DNA might be an almost perfect match, but their paw prints won’t be. 6. Acknowledge real-world procedure and bias The Centre for Forensic Science identifies four separate stages in the methodology of fingermark collection: ACE-V.

In Forensics, Val McDermid discusses a miscarriage of justice that occurred because of flawed procedure (pp. 134–7). A partial fingermark left at the scene of a horrific bombing in Madrid in 2004 was analysed in comparison with a suspect’s fingerprints. In other words, the A and C were not separate procedures. The examiner went looking for points of similarity rather than taking into account the differences, even though only a partial fingermark was available. This introduced unacceptable bias and led to erroneous findings. She summarizes the FBI’s later conclusions:

Does this mean you can’t have flawed procedure in your novel? Not at all – it could be a great plot point. Just bear in mind that the issue of bias is on the agenda for the forensics community internationally. Read ‘A Review of the FBI’s Handling of the Brandon Mayfield Case’ in its entirety if you want more insights into the challenges of fingerprint forensics. Furthermore, many police forces are having to endure budget cuts. Stretched resources can lead to corner-cutting. How might that affect your story? 7. Familiarize yourself with processing and enhancement Latent fingermarks are currently processed using the following techniques. To find out more, read Dr Chris Lennard’s paper, ‘The detection and enhancement of latent fingerprints’, presented at the 13th INTERPOL Forensic Science Symposium.

Exemplar fingerprints – those taken directly from an individual in controlled circumstances – are captured via two methods:

Read about how two law-enforcement organizations – one in the UK and one in the US – use ink and scanning technology here:

8. Use the right fingerprint databases Images of fingermarks extracted from a crime scene can be uploaded to databases containing both fingerprints (and other biometrics) of known individuals and fingermarks that have yet to be identified. The main fingerprint databases are:

9. Decide how far to bend the rules Do you need to worry about any of this? After all, it’s fiction! It depends on the subgenre of your writing, and how your readers are likely to respond to deviations from reality. If your novel is set in an alternative world or in the future, you can play it however you want. If, however, you’re writing a realistic procedural, you could alienate sticklers if you get it wrong, especially those who are police officers, forensic scientists, scene-of-crime officers, and fingerprint examiners. TV shows like Silent Witness and CSI offer audiences a single viewpoint. Most viewers accept that the real world involves more complex investigations with many more players. Books, like TV shows, entertain us, so readers too will indulge writers who bend the rules to a degree. Even if you don’t want to go for maximum authenticity, consider sprinkling your narrative with factual information that grounds your investigation just enough to head off those whose fingers are hovering over the one-star button in Amazon’s review pane! Further reading and related resources

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Not every reader can stomach violence in fiction, and not every writer wants to go the whole hog with it. Here are two ways to approach it: compressed reporting after the fact; and showing it all as it happens.

Compressed reporting after the fact

Reporting the outcome of violence after the fact can be a superb alternative to detailed descriptions that might upset or sicken authors and their readers. This technique is used on the screen too. In Series 5, Episode 3 of Line of Duty (BBC1), the perpetrator breaks into the home of a core character’s ex-wife. The transgressor proceeds to torture the victim. There’s a drill involved and lots of screaming. It’s gross. Well, it would be if we saw it. But we don’t. All we see is the outcome. The ex-wife lies in a hospital bed, bandaged from head to toe. We glimpse patches of skin, her flesh swollen and angry. Her face is physically untouched though trauma is etched into it. And even the slightest movement results in a whimper and a wince; despite the medication, she’s in pain. All we know so far is that something awful has happened to her but we don’t know what. The scene cuts to two police officers listening to an audio file of the torture. Now we hear the drill and the screams. The officers play a little of the audio then switch it off and express their horror. A phone conversation with the victim’s husband ensues and we discover a little more about what’s been done to the woman. They finish the call and discuss the crime between themselves. Then the audio’s back and we hear a few more snatches. Off again, and there’s more analysis. It’s a powerful rendition of extreme violence that protects viewers from the gory detail but leaves us in no doubt about the suffering that’s been endured. This method can work just as beautifully in a novel. It’s not that the violence is diminished but that we access less of it. Harlan Coben’s Run Away (Century, 2019, pp. 68–9) provides an excellent example. Aaron, a corrupt and possessive junkie, has been murdered. Coben elects not to show us the violence as it plays out. Instead, we learn what happened via a later conversation between Simon and Ingrid.

Two things stand out about this scene:

Cosies are a subgenre that bend particularly well to compressed after-the-fact reporting. Yes, people get hurt and die in grisly ways but most of the horror is left to the imagination. Here’s an example from Emily Brightwell’s The Inspector and Mrs Jeffries (C&R Crime, 2013, pp. 1–3):

Brightwell focuses on the impact of the poison on the body; unlike in the Line of Duty screen example, there’s nothing that tells us about the suffering endured. That’s the cosy way. And as with the Coben example, the implied violence is balanced by dialogue that unveils character personality. It’s not just the readers who shy away from the horror; Inspector Witherspoon does too. We also learn how he’s perceived by others in the scene – as a bumbling buffoon who can’t see the obvious. This sets the scene nicely for Mrs Jeffries’ more capable intervention later on in the novel. Showing it all as it happens Some acts of violence – such as fight scenes – work best when we’re shown everything as it plays out. Rendering a fight after the fact (as in the examples above) would destroy the dramatic tension. Still, a fight scene needs to hold the reader’s attention. That means paying attention to pacing and providing just enough stage direction to enable the reader to understand the choreography. This extract from The Poison Artist by Jonathan Moore (Orion, 2014, pp. 244–5) appealed to me because it avoids high-octane, kickass tropes. Rather, the author captures the transgressor’s mysterious sensuality in the violent narrative. Her psychotically calm speech and composed movements have an ethereal quality. In sharp contrast, the protagonist’s actions are punctuated with sentence fragments that elevate the pace and introduce tension.

Moore, like Coben, doesn’t overwork it. The scene never drags even though the pace changes depending on who we’re watching. Here’s a high-octane example from Robert Ludlum’s The Matlock Paper (Orion, 1973/2005, pp. 268–9). Ludlum never bores us, just tells us straight. The pace is quick and every word counts.

Ludlum keeps the stage direction lean and the pace consistent. But I also love how he introduces the earth and rain into the narrative, but only briefly. The weather doesn’t distract us. The mentions are just enough to ground the violence in a physical environment that can be felt and heard; the men aren’t fighting in white space. Lean is good but not too lean! Omitting the detail would render the scene inauthentic. Imagine reading this:

Lamaison saw his chance, and he took it. But Reacher was ready and took him down. Game over.

Really? So how did he manage that? Was is that easy? Jack Reacher’s good but he’s human. Readers still need to know how he won the day, how he was challenged, what obstacles he had to overcome. That way we can rally behind him. Here’s the real extract from Lee Child’s Bad Luck and Trouble (Bantam, 2007, p. 492). Child gives us the detail, shows us the choreography of the fight, but it’s focused. None of the steps are repeated so we don’t get bored.

Child uses sentence fragments to accelerate the pace, and polysyndeton to introduce a sense of rampancy. And he deepens our interest by shifting the narrative distance – we move from observers in the wings to right inside Reacher’s head. Summing up For showing-it-all violence:

For reporting-after-the-fact violence:

A final word. If your scenes of violence include weapons or specialist fighting techniques, do your research. Some of your readers will know their guns and martial arts. Placing suppressors on pistols that don’t take them or getting your martial arts moves wrong will pull readers out of your story and provide the pedants with excuses to knock stars off your Amazon reviews. Further reading

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with independent authors of commercial fiction, particularly crime, thriller and mystery writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Society for Editors and Proofreaders (SfEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and an Associate Member of the Crime Writers’ Association (CWA). |

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed