|

Story-level critiques focus on the big picture – plot, pace, characterization, voice. Line critiques evaluate a book at a micro level, focusing on sentence construction, word choice, and readability. Here’s an overview of what to expect.

Story first ...

Think of your book as a construction project. First you lay the foundations and build the walls – writing and redrafting to ensure the structure of your storytelling is sound. It’s where you and your editor (if you have one) focus on the big-picture stuff such as:

At this macro stage, you might end up adding, deleting or shifting sections of your prose. Some authors do their own structural editing because they’re good at it and have studied story craft via writing courses, groups or books. Others seek professional help, either because they’re at an earlier stage of their authorial journey or because they feel they’re too close to the book to see the problems. One thing’s for sure – there’s no right or wrong way. Every writer has to make their own choices. If a full, done-for-you developmental (or structural) edit isn’t the path you take, you might still decide to work with a specialist editor who analyses your book and provides a detailed report on its strengths and weaknesses at story level, and offers suggestions about how to improve your writing. That’s where story-level critiques come into play. You might also hear them called manuscript evaluations and manuscript assessments.

Line level second ...

Once the foundations and walls are in place, it’s plastering time – smoothing at sentence level to ensure that a reader’s journey through the pages is satisfying. In a sense, it’s still structural work but at a micro level. This is where you (and your editor if you have one) focus on nuances such as:

Again, some authors do their own line editing because they’re good at it and have studied line craft via writing courses, groups or books. Others seek help. If a full, done-for-you line- and copyedit isn’t an option, a line critique could be just the ticket. A line critique, like its story-level sister, is an assessment or evaluation of your story but at sentence level. Your report will include examples from your novel that show what’s holding you back. You’ll also be offered suggestions on how you can fix any problems identified. Then you can implement what you learn throughout the rest of your book.

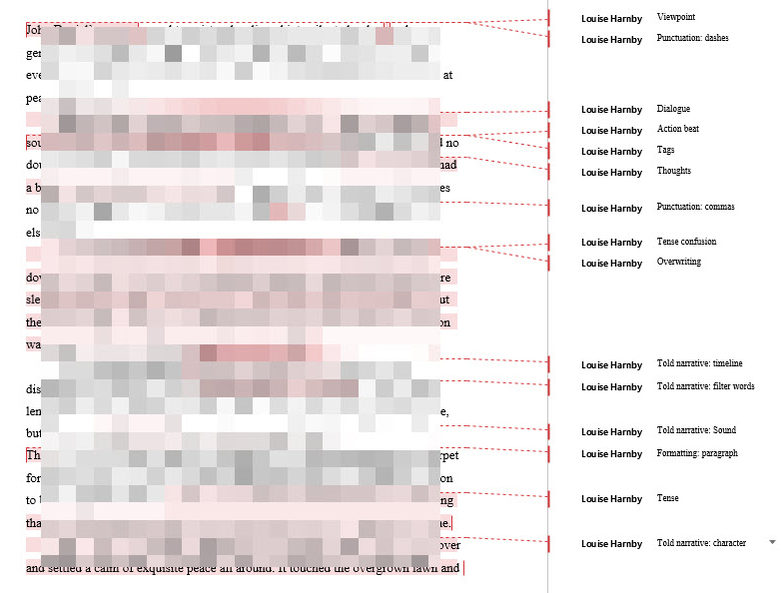

Critiques are about learning, not criticizing

Some authors are nervous about critiques. Pro editors get it – it can be tough to put your book in the hands of another and ask them to tell you what’s working and what’s not, especially when you’ve put in so much hard work. The thing to remember is that a critique (whether at sentence or story level) is not about criticism. It’s about identifying strengths and weaknesses, and offering solutions so that you can move forward to the next stage of your publishing journey with confidence. And critiques are a long-term investment. They enable you to improve your self-editing skills. That’ll save you time and money further down the line because anyone else you commission will have less to do. The line critique: the process and the report What follows is an overview of the way I handle line critiques. Every editor has their own process, but the basic principles will be similar. 1. The service: Mini line critique Authors email a Word file comprising, say, 5K words of their novel. It’s in a writer’s best interest to include a section that includes both narrative and dialogue. That way we can assess whether both are working effectively. Furthermore, if there are multiple viewpoint characters in the novel, and different viewpoint styles and tenses have been used, a sample that represents these choices will enable us to provide a report that evaluates the success of those decisions. 2. First readthrough The first stage of the process is a complete readthrough of the 5K words. It’s not about micro-level reporting, not yet. Rather, we’re getting a sense of the author’s writing style, the characters’ voices, and the flow of the narrative. 3. Second pass: Identification tagging We go back to the beginning and start the analytical process, identifying the strengths and weaknesses of the author’s line craft. We work through the sample, tagging sections of the text with Word’s commenting tool. The author won’t see these tags – they’re just a tool that allow us to locate the sections we’ll pull from the text and into the report for demonstration. The text in the image below has been blurred in order to respect confidentiality, but you can see the tagging process in the margins of just one page of one of my reports.

4. Writing the report

Now that we’ve tagged the sample, we can create a report. Line critiques are usually between 20 and 30 pages long, depending on the length of the text samples the editor is pulling in and offering recasts for. Each report is divided into sections that address the strengths and weaknesses of the following: NARRATIVE

DIALOGUE AND THOUGHTS

TECHNICAL ELEMENTS

FORMATTING

The tags in the sample allow editors to search for and locate the text we want to use as examples of good practice and to highlight areas with improvement potential. Here’s an example of one of those sections (I’ve disguised the identifying traits of the original in order to respect the author’s confidentiality):

CLARITY OF NARRATIVE VIEWPOINT

What worked You held narrative viewpoint well and I commend your decision to separate the two viewpoint characters with chapters. This ensured the narrative voices remained distinct. Using a present-tense second-person POV for your transgressor and a past-tense first-person POV for your protagonist worked extremely well. Have you read Complicity by Iain Banks? He does the same thing! It’s effective because it makes us wonder whether that first-person narrative is reliable, though you don’t give the game away until the denouement, which I loved. The second-person POV also lent a rather creepy voyeurism to the transgressor chapters, and though these were demanding to read, you did give your readers plenty of breathing space with the contrasting protagonist chapters. Nicely done! What could be improved Your protagonist narrative was laboured at times because of the abundance of ‘I’. Overusing this pronoun can lead to an overly told narrative in which the reader is forced to experience everything via the character’s experience of it. This can be distancing. I’m not suggesting you remove every instance of ‘I’ plus the verb – not at all. Instead, consider toning it down and removing some of the filter words so that the reader can experience some of the doing with the character rather than through the character. Here are two examples and suggested fixes:

Notice how I’ve suggested removing ‘I saw’, which feels redundant given that we already know that Marcus is looking up, and only tells us of more seeing being done. Instead, you can focus the reader’s attention on the immediacy of what’s seen once the looking up’s happened: the movement of the shooting star. That allows you to show readers what Marcus sees rather than telling them.

Notice how in the original there’s a lot of telling of what ‘I’ did. I like your use of a strong verb to introduce tension – ‘scuttled’ – but that tension dissipates with the more distant told narrative that follows. There’s telling of sound, smell, and realization. I’ve suggested you tighten up the paragraph by retaining the original anchor in which Marcus hides; perhaps follow that with a shown narrative that, again, allows the reader to experience the sounds and smells at the same time as Marcus rather than through his ears, nose and brain’s doing hearing, smelling and realizing. Recommendation Bear in mind that a first-person narrative, by definition, puts the reader in the character’s head. If you keep that in mind, you’ll save yourself a lot of work because you’ll need fewer words on the page. Have a read through all the protagonist chapters and consider where you can tighten up the prose in order to limit some of the telling of doing being done. You can still anchor the first-person viewpoint with ‘I’ in places, of course, but you might recast some of writing that follows with shown action. 5. Wrapping up and emailing the report When the report is complete, we save it as a PDF and email it to the author. PDF is the tool of choice for many editors because it can’t be edited. If the client wishes to refer back to it during future writing projects, they can do so safe in the knowledge that nothing’s been accidentally removed. Summing up If you want to hone your line craft and polish your book at sentence level, but a full line- and copyedit is beyond your budget, consider a more affordable alternative: the line critique. Think of a critique as another form of authorial development, of book-craft study. And what you learn from your critique won’t be something you can apply just to the current book. It’s a tool you can use with every story you write thereafter. And here’s a free booklet that outlines the various levels of editing. Just click on the cover to get your copy (and, no, you don’t have to give me your email address!).

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

7 Comments

It doesn’t matter a jot to me which kind of English an author wants to write in. What does matter is their readers' expectations and perceptions, and being consistent.

This free booklet shows you how to stay on track. To get it, head over to the Grammar and Spelling section of my Resource Centre.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Macros enable us to edit faster and more consistently. For professional editors, that means a higher hourly rate, a more consistent output, and a happier client. If you want to use macros but don’t know where to start, read on.

Which macros, and when and why?

Which macros should you use? How does the Paul Beverley macro suite fit with an application such as PerfectIt? What should you use when? No one’s the same. We edit different subject/genres, carry out different types of editing, and have different styles of working. There’s no one size fits all. A conceptual approach, however, can help us decide which tools to use. Analysis: Tasks versus goals A task-centred analysis focuses on what we plan to do and deciding what tools will help with these stages. Thus, in the free book, Macros for Editors, I offer smorgasbord of macros that speed up a variety of specific tasks. However, when we look broadly at what we’re trying to achieve, we may discover different ways of working and different tools – new tools, maybe – that can help. One such contribution to this approach is the Alyse suite – analysis-type macros (DocAlyse, HyphenAlyse, etc.) that provide an overview that reports on the likely inconsistencies in a document without our even having to look at the files.

Computer-aided editing: Teamwork

Think of computer-aided editing as teamwork – you and the computer working together, each playing to your own strengths, with a single aim: to improve communication between author and reader. A computer brings the following to the team:

On the downside, it lacks the ability to look beyond the data. It has no idea of meaning, significance, attitude, feelings – only humans can provide that. Mechanics versus meaning Editors spend a lot of time eliminating inconsistencies in the following:

This is the mechanical side of editing. Editors also spend a lot of time focusing on meaning. It matters little how consistent a document is if the meaning is clouded. Obscure the meaning, and communication between the author and reader is impeded. Using macros and related applications enables the editor to delegate some of the mechanical work to the computer – those mundane data-led tasks – and focus their minds on communication. A possible workflow Here’s one way it might look:

Here are the macros you might use in that workflow:

If you’re a PerfectIt user (see the Intelligent Editing website), you could use that instead at stages (3) and (5). Or continue to use FRedit for (3) but use PerfectIt for (5). The latter is a possible best-of-both-worlds approach if you like the idea of having two different tools, each working to spot errors that the other might have missed. False positives False positives are to be expected with any computer tool. We can reduce them by refining the FRedit changes list and PerfectIt’s style sheets. For best effect with global change macros, apply them to one chapter at a time, making adjustments that will make it more effective in succeeding chapters. Summing up To access all my line-level and analysis macros, download the free book. You can also watch almost 100 video tutorials on my YouTube channel. And if you want to know more about PerfectIt, visit the Intelligent Editing website. Please feel free to email me with suggestions and/or questions about macros.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses. Editorial training without borders: Should you bother with international editing conferences?9/10/2019

Does your editorial conference budget include provision for travelling abroad? If it doesn’t, here's why you might want to consider it and what you need to factor in to make it viable.

I’m a Brit who’s been to three editorial conferences in the past 12 months. Two of them required me to pack my passport.

First up was the one day mini-conference hosted by the Society for Editors and Proofreaders Toronto Group. I travelled to Canada in early November. I bought a new winter coat for the occasion because Toronto in November is cold cold cold. The weather foxed me – it was balmy – but the conference was everything I expected. Brilliant. Nine months later, I headed for Chicago, this time for the Editorial Freelancers Association meeting. The sunshine came as promised, not just on the lake shore but in the Swissôtel, too, where the conference took place. I received a lovely welcome and had a ball. Three weeks after that, I was learning again, but this time in the UK. The annual Society for Editors and Proofreaders conference took place at Aston Business School. Rain threatened but never arrived, and the meeting was smashing. Three different conferences. Three different countries. And one thing in common ... The delegates were international. And that’s the thing about the editorial community – we’re from everywhere, and our conferences reflect that. Still, attending conventions, especially those abroad, means an investment in money and time for the professional editor, so why bother?

Being an editor isn't a national occupation

Our clients don’t all live where we live. Take me. I’m a Brit but I’m not an editor of British novels. I’m an editor of novels written in English ... or I should say, Englishes. And as all pro editors know, there is more than one English. And while those Englishes come with variances in spelling, punctuation, grammar conventions and idiom, all of that can be learned and understood. And that's one of the pulls of international conferences. What better way to hone your craft than by spending time in the places where those Englishes are spoken and written, and hanging out with the people who speak and write them?

Other factors to help you decide

Here are some ideas to help you decide whether to cross the border for your editorial training: 1. Look at the conference programme Are there sessions on aspects of editing, or the business of editorial work, that you can’t access elsewhere? For example, take a look at the 2019 Toronto SfEP mini-conference programme (Wednesday, 6 November). You can learn how to identify the missing parts in a fiction narrative, how to use macros, how to master templates, how to edit indexes, and how to tackle fast-turnaround editing. There’s also an optional pre-conference workshop on raising rates. 2. Who's speaking? Are the presenters offering learning opportunities that will be easier to learn face to face? Or perhaps there are keynoters or after-dinner speakers you’d be unlikely to meet otherwise. At the 2019 SfEP conference in Aston, bestselling crime-fiction author Chris Brookmyre , linguist Rob Drummond, and broadcaster/writer David Crystal were all on the schedule. We learned hard ... and laughed harder because all three make what they teach memorable through humour. 3. Can you leverage being an international speaker? Think about whether speaking at editorial events beyond your borders is something you can leverage professionally and that will pay back your investment in the long run. Some of our potential clients value knowing we have international speaking experience because it reflects a global trust in our specialist knowledge. 4. Is an honorarium available? If you’re prepared to speak on a specialist topic, you might qualify for financial support. Of course, this depends on the organizer’s budget and the value they think you’ll bring to the conference, but editorial societies are increasingly recognizing the benefits of international speakers in view of the global nature of our community. Don't assume that assistance isn’t available. Even a contribution to flight, accommodation or meals might be the tipping point for your saying yay rather than nay. 5. Can you buddy up to reduce costs? If a flight’s involved, you’ll have to bite the bullet. If you can drive across the border, however, you can share the cost of travel. And how about sharing a room? I did this with my podcast pal Denise Cowle at the 2018 ATOMICON marketing conference. We halved our costs. And neither of us snored. Promise. We’re talking about doing ACES in a couple of years. Being Airbnb buddies will be one way we’ll make it viable. 6. Find out who else is going Face-to-face networking is powerful. Spending time with international colleagues could lead to referrals that will earn you a return on investment further down the line. And if you have books, courses or other training materials relevant to your editorial colleagues, you could reach new markets when you take the time to put yourself in front of your audience and speak at an international event. We’re much more likely to buy from those we trust, and while online networking is great, and the online editorial community is vibrant and generous, nothing beats getting in front of people, talking with them face to face, when it comes to building relationships and trust. 7. Cost it out and save up Work out what it’s going to cost. It’s all very well my talking about the benefits of international networking and learning, but I’m not going to pretend there isn’t hard cash on the line here! Costing it out is the first step to creating a savings plan. That way you can prepare ... if not for this year’s meetup then for one a year or two down the road. Start with the basics:

Summing up International conferences require more planning and a bigger investment of time and money, but if you’re canny about your preparation, think in the long term, and use them as opportunities to speak, they’re hugely beneficial. Where will you go next? Maybe I'll see you there!

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

If your characters seem or appear to be doing or feeling something – probably, maybe, perhaps – then you might be using half measures to express a good chunk of that action or emotion. Uncertainty can drag a story down. Here’s how to edit for it at line level.

In fiction, tentative language can lead to the following:

Authors sometimes introduce tentative language into a novel because:

Tentative language: words to watch out for I’m not suggesting you remove every tentative word; some might be deliberate and necessary. More likely, you’ll be checking that your prose isn’t rife with them. Still, these little blighters can slip in accidentally and it’s worth taking the time to root them out and decide whether to give them space on your page or remove them. Here are some of the words (or word groups) to watch out for:

When there’s a problem, it can sometimes be fixed with a simple deletion, or a stronger verb. When viewpoint, tension and reader immersion are at stake, more intervention might be required. How to fix it without dropping viewpoint I see the likes of seemed, appeared, and looked as if creeping frequently into line editing projects for less experienced authors because they want to hold viewpoint. Hats off to them – I’ll take a seemed over a head-hop any day of the week! Still, there might be a better fix. Here’s a framework you can use to recast in a way that removes the uncertainty but keeps the narrative alive.

In the examples below, I’ve used this framework to craft a shown narrative rather than an assumed one. The original text is based on real examples that have been adapted to respect confidentiality.

EXAMPLE 1

Luke peeked around the headstone. The hooded man seemed frustrated.

Luke can’t know for sure how the other character is feeling, and the author covers this with seemed. That’s all well and good; removing it would flip the reader from Luke’s internal experience to the hooded man’s.

The sentence is flat though. Yes, we readers are still in Luke’s head but it’s not a particularly interesting space. There’s no tension in our observations from his hiding place. Here’s how the fixing framework helped me recast in a way that shows readers the hooded man’s assumed frustration, as seen by Luke: Luke peeked around the headstone. The hooded man glanced at his watch and swore under his breath. His foot lashed out, knocking over a grave vase. The stagnant water stunk and Luke wrinkled his nose.

In the revised version, we see the hooded man’s emotion through his action. That helps with the flatness but also with narrative distance; we stay close to Luke because we experience not only what he sees but also what he smells. It’s more immersive.

EXAMPLE 2

Thom turned and tripped over the blind guy’s white stick – Mikey, someone had called him. He looked at Mikey, who seemed almost to be picking out Thom’s facial features in his mind.

Thom is the viewpoint character so we can’t know what’s going on in Mikey’s head. And that means we can’t just remove the tentative words and change the verb to picked.

But there’s a problem. If Mikey were the viewpoint character, his imagining Thom’s face would make for an interesting narrative. However, it’s Thom’s head we’re in. In this case, the assumption seems off, too big to believe. When I listen to someone speaking, I tend to use my eyes to focus on their mouths; my friend with restricted vision tends to move his head so that his ears are more in play. Sighted people in his company need to be aware that his eyes don’t focus directly on a speaker even though he’s fully engaged. If we place this experience within the fixing framework, we can imagine Mikey’s physicality and the effect on Thom, the viewpoint character. Thom turned and tripped over the blind guy’s white stick – Mikey, someone had called him. Mikey tilted his head, gaze off-centre, ear trained on Thom’s blustered apology.

In the revised version, the assumption is gone. Instead, readers are shown what Mikey does and what Thom experiences. Viewpoint is intact, and the clunk has gone.

How to fix an insecure narrative voice In the examples below, the tentative words have crept in because the authors are still developing the confidence to make every word count. Useful tools of the trade include deletion, stronger verbs, smoother recasts, and free indirect style. The fixes below are suggestions only, offered so you have an idea of what to look out for and how you might tackle the solution. The approach you use will depend on your writing style and the mood of the scene. When tentative language creates a flat sentence In these examples, the tentative mood is justified but the sentences are rather flat. We need to inject tension.

When tentative language creates a woolly sentence

In these examples, the tentative words relate to viewpoint characters’ experiences. The uncertainty introduces distance because it pulls the reader out of their experience. It makes us say, ‘Why the lack of commitment? Doesn’t the viewpoint character know?’ Once more, I’ve used real examples and adapted them to disguise the originals.

When tentative language works

In these examples, the tentative words work. They show the reader that the viewpoint character is guessing. She glowered as if to say, You really think there’s enough meat on that plate? Mark glanced at the blue car. There were two people inside, neither familiar. Might be undercover cops, but he legged it anyway … just in case. A haze hung in the air – maybe brick dust from the fallen building or ash from the fire. It stung his eyes and irritated his throat. The news knocked the breath out of her. Jamie had seemed happy the last time they’d met. Ecstatic even, what with the new job, the kayaking holiday, that girl he’d met the week before. She combed the beach for Ben’s blue sun hat, pushing the unthinkable to the back of her mind. Thought it through. Probably with Mark at the rockpool. The café maybe. Or the groyne or the dunes. Her head spun left, right, left again. Summing up As soon as a writer or editor begins line editing fiction, subjectivity comes into play. It’s rare that there’s a right or a wrong way. With that in mind, don’t ban tentative language in your prose; just watch out for it. It may well have the right to be there, though it shouldn’t trump tension or add clunk. If removing it messes with viewpoint, use the fixing framework to craft an alternative shown narrative.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

|

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed