|

Find out more about opportunity cost, and why editors and proofreaders need to keep an eye on this part of their business.

|

|

Online editing training course

|

Classification in UK

|

VAT must be charged to UK customers?

|

|

EXAMPLE 1

|

Digital service

|

Yes

|

|

EXAMPLE 2

|

Not a digital service

|

No

|

|

EXAMPLE 3

|

Probably not a digital service

|

Probably no

|

|

EXAMPLE 4

|

Possibly not a digital service

|

Possibly no

|

|

EXAMPLE 5

|

Nebulous

|

Nebulous

|

Your online course and the tax authority in other jurisdictions

Anyone offering online courses in a global market must know where their customer lives. And it’s the tax authority’s rules in the customer’s jurisdiction that determine whether we need to add a consumption tax to the price.

Which can be a monumental barrier for sole-trading editors and proofreaders. Why? because here's what we need to take responsibility for.

Our consumption tax responsibilities

Small-business owners selling digital products and services internationally must have a mechanism in place to:

- ensure that our customers provide the necessary jurisdiction data on our invoices

- allow our customers to exempt themselves from the tax where appropriate

- calculate the appropriate tax rate for every customer

- review that tax rate regularly (because they change!)

- collect the tax from the customer

- remit the collected tax to every single relevant tax authority. That's right. Every single one.

That list is enough to deter any small-business owner from sharing their knowledge and charging for it. Which is a crying shame because the editorial community is passionate about training and CPD.

And the fact is that most of us don’t have the time or skills to do this work – unless we decide we're not actually going to be editors and trainers anymore, but full-time accountants instead.

Nor can we afford to hire an expensive specialist tax accountant who will do this for us – unless we want the entire exercise to become unprofitable.

So what do we do?

The solution: Find a taxation-friendly training platform

What is a Merchant of Record?

A Merchant of Record is the legal entity that usually:

- calculates the appropriate rate of tax that needs to be added to a purchase of your course

- updates that rate of tax rate in your payment gateway when necessary

- collects that tax from your customer

- remits it to the tax authority in the appropriate jurisdiction.

When we choose a training platform that acts as the Merchant of Record, or includes a third-party integration that does the same, that leaves us free to get on with the business of editorial training rather than worrying about whether we’re tax compliant in every part of the world we’re selling to.

If the platform doesn't offer that, we're the Merchants of Record, and the buck's back with us.

What’s on offer?

Some training platforms are partial Merchants of Record. PayHip, for example, calculates, collects and remits VAT in the UK and Europe for me as a UK resident. However, I’m responsible for the tax compliance in all other jurisdictions ... Cue the worry.

Some training platforms include integrations that calculate the tax but don’t collect or remit it. That’s on us or our (expensive) specialist tax accountants. LearnWorlds is an example. The Quaderno app calculates what we owe to whom, but we have to do the rest ... Cue the worry.

Some training platforms act as full Merchants of Record, meaning they calculate, collect and remit all the tax for all jurisdictions. Teachable is an example ... And relax!

Where I host my editorial training courses

- It acts as a full Merchant of Record, meaning I can focus on course creation rather than worrying about tax compliance.

- The platform is super user-friendly for me and my students.

- Teachable has a gorgeous app (iOS and Android), which is fantastic for students who want mobile access. Download it from your usual app store.

- I can brand my content appropriately.

- Multiple editorial trainers use Teachable, which means students can access our schools via a single platform.

- I can now offer payment plans that allow my students to spread the cost.

- And there's a bundles option that lets me offer you access to multiple courses ... and with big discounts!

Note that at the time of writing, trainers wanting to offer PayPal as a payment gateway in Teachable must set their course prices in US dollars.

Teachable is right for me, but any editor or proofreader embarking on online course creation should do their own research. Most platforms offer a free trial so you can get a feel for the setup, functionality and branding options.

Summing up: What to consider

- Creating and delivering online courses for editors and proofreaders has never been easier thanks to the growing number of platforms with user-friendly interfaces and multimedia functionality.

- What’s not so easy is the tax-compliance element. Many of the providers haven’t yet woken up to the implications for small-business owners operating in a global marketplace with complex and ever-changing tax rules.

- If you’re planning to teach online, make sure you understand the differences in tax rules for courses with a live component and courses that are self-directed, not just in your own jurisdiction but elsewhere too. Also bear in mind that what constitutes live tutoring might be nebulous.

- And, finally, if you decide to head down the self-directed training route, and your preferred platform isn’t offering a full Merchant of Record service, think carefully about who’s going to do that work and how much it will cost.

Related resources

- Check out my courses, their payment plans, and discounted bundles.

- Visit my Skills and training resource page to access free guidance.

- Find out how to log in and access courses you've already purchased.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Fellow editor and Excel authority Maya Berger has created a tool that will make life easy. It’s called The Editor's Affairs (TEA).

When it comes to keeping an eye on the health of my business, simple has always been my goal. I’m an editor, not an accountant.

Essentially, I want as much as possible in one place:

- Project schedule

- Project data

- Business income

- Business expenses

And when it’s time to submit a tax return to (in my case) HMRC and evaluate how things are going, I don’t want to be faffing around with several different apps and spreadsheets.

Instead, I want to see the core data at a glance … data that will tell me the following:

On a project basis:

- Hourly rate

- Start and end dates

- Fees – quotes, paid, pending and overdue

- Baselines data – word count, hours worked

- Client name, project title, how they found me

On a business-health basis:

- Which clients I earn the most money from

- The worth of each client as a percentage of my total income

- Which months are the most lucrative

- Average hourly rates

- Average speeds

- Comparison of data with the previous year

- Income to declare

- Allowable expenses to offset

I don’t want to spend ages collecting and collating this data so it’s easy to access. I want summaries that give me a number – automatically generated by the data I’ve inputted throughout the financial year.

Then, when it’s time to review my business and submit my return to the tax authorities, the numbers are ready and waiting for me.

I’ve been tracking my data for years, and while I’m fairly proficient with Excel, I’ve been aware that there’s more I could do to fine-tune my process. However, like many editors, I have neither the time nor the will. So when Maya asked me to take a look at TEA, I jumped at the chance.

So what is TEA? It’s a one-stop-shop Excel spreadsheet with lots of built-in jiggery-pokery that does all the tricky formula work for you. All you need to do is input the project (and expenses) data as it comes in.

Below are examples of some of the project data an editor can input, and the received data from TEA.

Examples of data the editor can input

- Invoice number

- Start date

- Finish date

- Date of completion

- Payment due

- Payment date

- Client name

- Notes about the job

- How the client found me

- Total word count

- Estimated words per hour

- Desired hourly rate

- Actual number of hours worked

- Amount invoiced

- Amount received

Examples of received data from TEA

- A status alert if the invoice is overdue

- An estimate of actual words/hr

- An estimate of how many hours I’d have to work to achieve my desired hourly rate

- My actual rate per hour

- My actual speed

- My actual rate per 1,000 words

- The amount I need to quote to achieve my desired hourly rate

So why is it worth investing in TEA? I identified 5 standout features that I believe make this a must-have tool.

NOTE: The numbers and client information below are for the purposes of illustration only. I made them up because my business affairs are of no concern to anyone but me!

1. Making informed decisions when quoting

TEA allows you to see the impact of the data you’re inputting on your business, and make informed decisions about how you should quote. Let’s take an example:

John Smith asks me to line edit a 100K-word novel. I estimate I can edit at a speed of 1,750 words per hour, so I input that information along with the word count.

- TEA tells me I’ll need to set aside just over 57 hours for the project.

I decide I want to earn £40 per hour. I add that data to the row.

- TEA tells me my estimated rate per 1,000 words will be £22.86.

Now I can build my quote. I type 57 into the hours-worked cell.

- TEA tells me I need to quote £2,285.71.

For argument’s sake, let’s say I know that my client’s budget is £2,000. I can temporarily add this to the amount-received cell.

- TEA tells me my rate per hour would be £35.09.

If I’m happy to work for £35.09 rather than £40 per hour, I’m good to go. If I don’t, I can negotiate with the client. The point is, I can play with the data I’m inputting and see the impact. And that means there are no surprises. I’m making informed decisions.

2. Collecting data for the future

Less experienced editors might not yet have enough older data to know how long a particular type of editing will take, or whether Client A’s work tends to be speedier to complete than Client B’s. TEA helps us build that knowledge via accrued data that we can use later on. Another example …

In April 2019, Jackie Jones asks me to proofread her 30,000-word novella. I have no clue how long it will take so I estimate a speed of 5,000 words an hour. I’m grateful for the opportunity because my business is new. I decide I’ll be happy earning anything over £20 per hour.

TEA tells me my rate per 1,000 words will be £4 and it’ll take 6 hours, so I bill for £120. I get the gig and do the work. In fact, it takes me 10 hours. I input the new data.

- TEA tells me I’ve actually achieved only 3,000 words per hour and that my hourly rate was £12, not £20.

But I’ve learned something. And when Jackie comes back to me three months later with another job with the same word count, this time I can input more accurate data, meaning I’ll earn my desired rate of £20 per 1,000 words.

3. Saving time and protecting the data

At no time am I messing around with a calculator. All I do is input the raw data and review what TEA’s analysis cells tell me.

That saves me time because TEA’s doing the maths for me.

Plus, I can’t break the spreadsheet! TEA’s analysis cells are locked so I won’t inadvertently alter the complex formulae within.

4. Client analysis

Some editors work for repeat clients – an agency or publisher, for example. In those cases, we’re not always in control of the price, and yet those clients can still be valuable because of the amount of repeat work they send us and the percentage of our overall income their business accounts for.

Knowing who our most valuable clients are is essential if we’re to avoid knee-jerk reactions to rates of pay.

If Publisher A pays me an hourly rate half that of Agency A but gives me five times as much work, I’ll want to think very carefully before canning that client because I don’t like their pricing structure.

TEA’s Client Summaries Table does what is says on the tin. It’s here that we can see a list of our clients, the percentage their business contributes to our overall income, the number of hours’ work we’ve done for them and the total income received.

Time for another example …

Let’s say I’m scowling at the row on the Income sheet because I’ve yet to crack £15 per hour from Romance Fiction Press. Just above is an entry for John Smith, the indie author from whom I earned £40 per hour.

Terrible rates, I think. Exploitative, disrespectful, unfair. I’m about to head off to a Facebook group with 10,000 editor members and have a bit of a rant. Then I’m going to tell that press where to stick it.

But hang on a mo! What does TEA have to say?

I nip onto the Summaries sheet and take a look at the Client Summaries Table.

- TEA tells me that work from Romance Fiction Press earned me £11,000, which accounts for 54% of my annual income.

- John Smith is responsible for £2,285.71, or 11% of my annual income.

Yes, John Smith is a more valuable client on a project-by-project basis but he’s not giving me anywhere near the same volume of work as Romance Fiction Press.

Instead of ranting on Facebook, I need to use that time to plan a strategy that will bring in more John Smiths or better-paying publishers and agencies. Once done, I can phase out Romance Fiction Press. That might take a couple of years of intensive marketing. Until then, the press will stay.

Perhaps I can negotiate a raise with them. Maybe there are efficiency tools I can introduce to increase my speed when I’m editing for them. And they pay on time, are pleasant to work with, and have given me loads of fodder for my portfolio that I can leverage on my website and in future marketing.

The work is regular, too, and lands on my lap without my having to promote myself to get it. And that time saved is worth something.

5. Making tracking and tax less taxing

There are two additional and extremely useful summary tables in TEA:

- The Monthly Summaries Table shows income, hours worked, expenses and charitable donations compiled from basic data the editor places in the onboard income and expenses sheets. You can see which months are most lucrative. TEA gives you a sense of the degree to which your work is seasonal, and that helps you to plan ahead and promote your business appropriately if you want to fill some gaps.

- The Allowable Expenses Table has an itemized breakdown of what you can offset against your income.

The totals are the figures you’ll report to the tax office. They’re right there in front of you – no hunting around in different apps and other spreadsheets. All the data filters through from easy-to-fill-in Income and Expenses sheets accessible via TEA’s tabs.

Isn’t the name adorable? Using TEA is like having a cuppa! And it’s all about the editor’s affairs – our business affairs.

The data the editor has to input is basic stuff that all of us have access to or can estimate with every new job or expense that comes in.

The data TEA gives takes the stress out of scheduling, accounting and analysis.

Every editor needs to understand the health of their business so that they can make informed decisions about who they work with, how much they charge and where the value lies.

When accessing that data becomes burdensome, the temptation is to wing it. TEA means you don’t have to.

Maya will be making TEA available for purchase in May 2020. For introductory rates or to learn more about customized versions for more complex accounting and analysis, check out whatimeantosay.com/tea.

***

NOTE: I have no commercial stake in TEA, though I was given a free copy to experiment with in return for feeding back my experience of using it.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Perhaps the price or the time frame doesn’t work. Maybe the client has been in contact with an editor who’s a better fit in terms of skills and experience.

Still, there are steps we can take to maximize our chances of turning a request to quote into paying work.

Think of quoting as targeted marketing

Every request to quote is a marketing campaign with just one recipient. We have an advantage once we’ve been asked to quote – we’re probably competing with five or six colleagues, not five or six thousand.

Since the odds are so much better, it’s worth investing time in making the quote the best it can be. A couple of lines that include a price won’t cut the mustard – unless the client has specified that they want nothing more.

Acquire relevant information

Before we can reply, we need information – a word count, the type of editing required, the levels of editing that have already been completed, the client’s preferred time frame, and a sample.

If that information hasn’t been supplied, asking for it is legitimate. A professional editor can’t quote without it.

There are advantages too: it keeps the conversation going, demonstrates an understanding of the editorial business process, and creates a foundation for trust.

Frame with solutions

A potential client doesn’t want an essay – we do need to stay on point – but we can still frame our quotations in terms of solutions to problems.

- Solution-focused language demonstrates empathy.

- Being empathized with evokes positive emotions.

Once they’re in play, the conversation’s no longer about price; it’s about a relationship. If the client’s looking for the cheapest editor, yes, this tactic will fall flat. If they’re looking for a good fit, it will give us an edge.

Linking to or attaching useful resources builds empathy and trust.

Here’s what I included in a request to quote in addition to a price (the writer had included a sample):

- a booklet about the various levels of editing

- a booklet about punctuating dialogue

- a booklet about narrative viewpoint

- an article about filter words

Each of those resources complemented a short paragraph outlining problems I’d identified in the sample, and would fix if I were to secure the project:

- Viewpoint drops

- Telling rather than showing: too much exposition of doing been done that reduced immediacy

- Punctuation and standard paragraph layout problems

And the great thing is, I can use these resources over and over. Yes, it took time to create them but they’re evergreen.

Every author I send them to gets value from them. But every time I send them, there’s value for me too: a return on my initial investment in the form of an increased likelihood of securing the job.

A client who trusts

The writer thanked me profusely ‘for such a thoughtful reply’. I got the gig. And they agreed to wait 12 months and paid the deposit promptly.

I can’t prove that those resources nailed it for me, but those words – ‘such a thoughtful reply’ – tell me the client reacted emotionally to the empathy I’d shown.

Creating that kind of content is time-consuming but the job need be done only once. After that, the resource can be used in myriad ways: marketing, quoting, linking to in reports.

When the quote’s rejected

If we don’t get the gig, should we ask why? I don’t think so. It annoys me when I decline a service or product and am asked to give reasons for my decision. It’s my business, end of story.

Receiving feedback is useful for editors, of course, but we’re asking people who have chosen another editor to spend their valuable time engaging with us. Why should they? They have other priorities that don’t involve us and we need to respect that.

If a quote is rejected, move on and focus on improving your next quotation.

More resources on business growth and pricing

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

FIND OUT MORE

> Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

> Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

> Learn: Books and courses

> Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Instead, I want to explore some ideas about how to develop your spidey sense, and use language and tools that will repel those who’d let you down.

What does ‘delay’ mean to you?

The concept of the delay is nonsense to an editorial business owner.

If a client asks you to proofread a book, tells you the proofs will arrive with you on 10 May, and requests return of the marked-up proofs a week later, and you agree to take on the job, those are the terms: proofread to start 10 May; delivery 7 days later.

You’ll schedule the project accordingly, and will decline to work for anyone else from 10–17 May. If two weeks ahead of the start date you’re told ‘there’ll be a delay’, you’ll likely have no work for 10–17 May unless you can fill that space at the last minute. Moreover, you will be booked for another project during the period when the project will become available.

To my mind, that’s not a delay. You can’t magic additional hours out of thin air. That’s a cancellation of the project terms that were agreed to by both parties.

You might decide not to invoke it as a courtesy, but having it could reduce the likelihood of having to make the decision.

Is ‘deposit’ a strong enough term?

The word ‘deposit’ should be strong enough as long as the refund terms are clear. Still, you might want to couch your language along the lines of what editor and book coach Lisa Poisso calls ‘real money’.

I don’t refer to deposits in my terms and conditions. I call them booking fees. A fee is a payment. It’s the language of money. ‘Deposit’ as a noun has a broader mass-of-material meaning; as a verb it means to place something somewhere. Maybe, for some people, it has a softer feel to it.

The following might also work for you:

- down payment

- advance payment

- prepayment

What you charge upfront is up to you. Some editors charge a 50% booking fee rather than a flat rate. Some require one third to secure the booking, another third just before editing starts, and the remaining third upon completion of the project. You can define your own model.

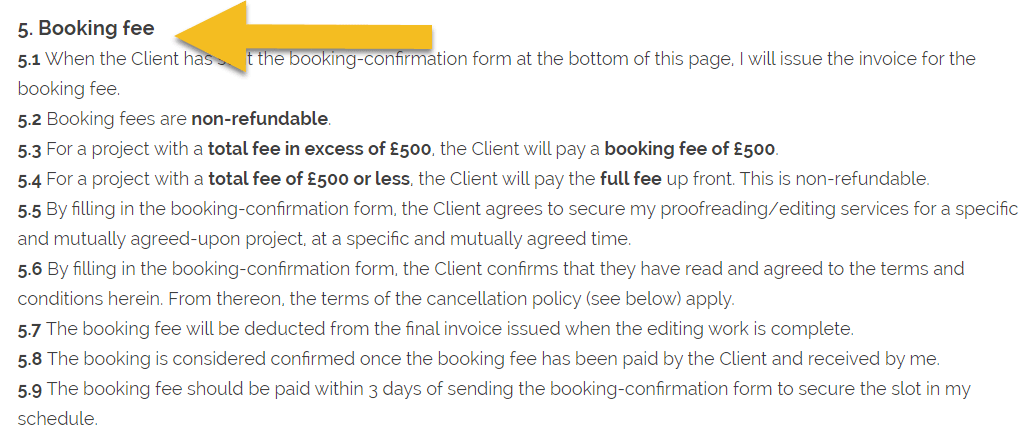

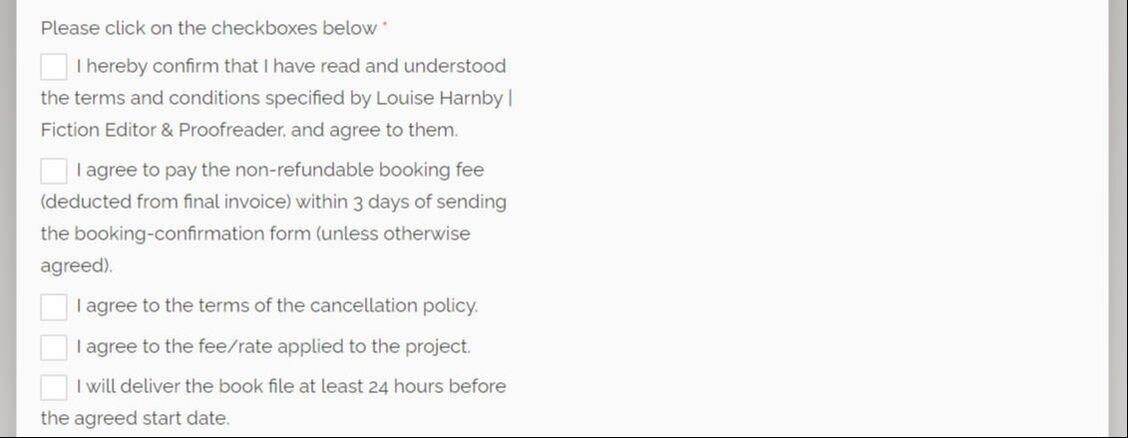

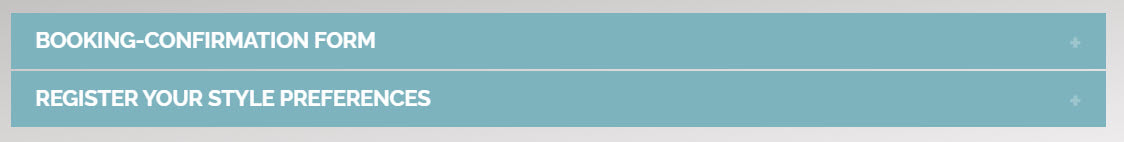

Do you have a booking form?

You and a client can agree to your providing editorial services via email, and emails count contractually. But how about requiring a specific additional action, one that reinforces a sense of commitment?

Asking someone to fill in a booking form that confirms they have read, understood and agreed to your terms and conditions, including your booking fee and your cancellation policy, means they have to make a proactive decision to commit.

When it comes to filling in a form and ticking boxes, a non-committed client is less likely to feel comfortable than a good-fit one because it feels more formal.

You can create a PDF booking form that you’ll email manually, or create the form on your website. My choice is the latter. I include it below my T&Cs. That way, the booking and the terms are closely linked.

Here’s a screenshot of mine. Notice the boxes that must be checked in order to confirm the booking.

Even if someone is prepared to fill in a form and check some boxes, agreeing to a contract might make them think twice. That has a more legally binding feel about it; it’s more formal. And it might be the thing that repels someone who’s going to let you down.

My T&Cs state that the booking-confirmation form is an agreement to the contract of services between me and the client, and the phrase ‘Contract of services agreement’ in the heading is what appears when they click on the booking-confirmation form button.

In the main, your website should be client-focused. It should make the client feel that you understand their problems, are able to deliver solutions, and understand what the impact of your solutions will be.

Your brand voice should sing out loud. In my case, for example, that means using a gentle, nurturing tone.

However, when it comes to your terms and conditions, forget all the touchy-feely stuff – this is where you and the client get down to business. It’s in everyone’s interests to know what’s what.

That might mean that your T&Cs are rather dull and boring. No matter. It’s the one place on your website where you’re allowed to be dull and boring!

I feel like chewing my own arm off when I read my T&Cs but I don’t want any of my clients in doubt about what I’m offering and what they’re getting.

Think about the following:

- How much do you charge for a booking fee or advance payment?

- What are the penalties for cancellation and when do they kick in?

- Is final payment required before the edited project is delivered to the client?

- If you’ll deliver first, will payment be required immediately? Within 7 days? Within 30 days?

- Are there penalties for late payment of the final invoice?

- Does your booking form require confirmation that your terms have been read, understood and agreed to?

A non-committed client will be repelled if your terms put them at risk. A good-fit client will feel reassured that they’re dealing with a fellow professional who takes the editing work as seriously as they do.

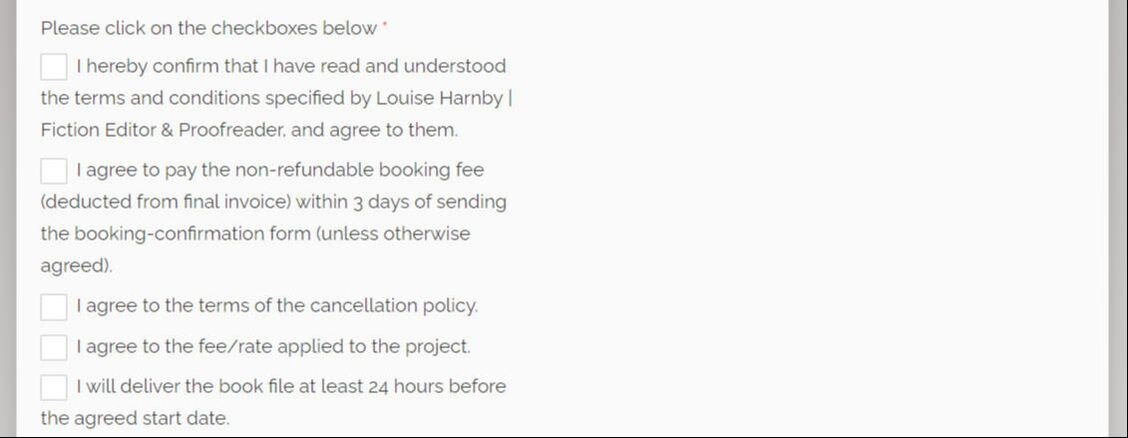

Are the basics front and centre?

Many editors place links to the detailed contractual stuff in their website’s footer, which means the T&Cs are almost invisible. Even a good-fit client probably won’t see or read your T&Cs during their initial search for editorial services.

That’s the case on my website. If it’s the same for you, consider placing the basics front and centre.

I’ve created a box on my contact page that spells out the non-refundable booking fee I charge.

Spotting red flags

Developing your spidey sense can reduce the likelihood of becoming entangled with those who’ll back out of confirmed bookings or fail to pay.

- The person tells you they want to go ahead and hire you for a specific time frame but doesn’t fill in the booking form, or you have to nudge them several times. This could indicate that they’re not yet committed to working with you.

- The person fills in the booking form but fails to pay your booking fee. This is a strong indicator that the funds are not in place, and might never be.

- The person fills in a booking form and pays the fee but seeks to change the terms they booked under. This is a strong indicator that they’re not in the right mindset to commit to your editing services.

- The person is consistently slow to respond to emails during the initial discussion phase, and needs frequent nudging about the state of play. This might indicate that they don’t take your business offering seriously.

- The person gives you conflicting information about what’s required, or repeats questions about money and dates that you’ve already answered. This indicates they’ve not read your correspondence properly, which could lead to problems later.

- The person hasn’t begun the writing process, or has but isn’t sure when they’ll finish. If you don’t keep in regular touch with the client to check the project’s on track – which is time-consuming – the project could go off the rails and you’ll be none the wiser.

Summing up

I hope these tips help you avoid non-committed clients and safeguard your business. Even if you implement some of my ideas, there are no guarantees unless you ask for 100% of your fee upfront. However, rest assured that most clients are honest, committed and trustworthy individuals who are a pleasure to work with.

As for those who blow you out, a few are scoundrels. Others aren’t but are thoughtless and haven’t taken the time to understand the emotional and financial impact of cancellations and non-payment. Others have got cold feet. And some have been struck by unusual or extraordinary circumstances like bereavement. Most don’t mean to cause distress or place editors in financial hardship, even though those are two very real potential outcomes.

By using real-money language and action-driving tools, we can build stronger bonds of trust with those who are serious about working with us, and repel most of those who aren’t.

More resources

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

- on the individual editor

- on which industry surveys and reports you read

- on the required turnaround time

- on the complexity of the project

First of all though, a quick word on whether you should bother and, if you do, what type of service you should invest in.

Do you have to work with a professional editor?

Not at all – it’s your choice. That’s one of the biggest benefits of self-publishing. You get to stay in control and decide where to invest your book budget.

However, I absolutely recommend that your book is edited ... by you at the very least, but ideally by a fresh set of eyes, and even more ideally by a set of eyes belonging to someone who knows what to look out for. And the reason for that recommendation is because 99.99% of the time, editing will make a book better.

We can all dream about first-draft perfection, but it’s pie in the sky for most, even those who edit for a living.

I’m a professional line editor, copyeditor and proofreader, and today I wrote a guest blog post for a writer. I wrote, and then I edited ... first for content, then for flow, then for errors. I found problems with each pass.

That’s not because I can’t write. It’s not because I can’t string a sentence together. It’s not because I didn’t edit properly in the first round. The reason I found problems is because writing is one process – editing is another:

- When we write, we’re focused on the telling of the story – and all writing tells a story of one kind or another, whether it’s fictional, academic, professional, technical or scientific.

- When we edit for content, we’re looking at the big picture – whether the structure works.

- When we edit for flow, we’re looking at the sentences – how they work and feel.

- When we edit for errors, we’re going even more micro – spelling, punctuation, grammar, consistency.

And the different types of editing attend to different kinds of problems and have different outcomes. Trying to do everything at once is like trying to mix a cake, bake it, ice it, eat it, and sweep up the crumbs all at the same time.

Breaking down the writing and editing processes into stages is a lot less messy, and the quality of outcomes is much higher.

Still, that has a cost to it, and it’s a cost that the self-publisher will have to bear because there’s no big-name press to bear the burden for them.

The independent editing market is global and diverse. Editors specialize in carrying out different types of editing. Some specialize by subject or genre. They have different business models and varied costs of living. And that means that despite what you might read in this or that survey, there is no single, universal rate.

Neither is there a universal way of offering that rate:

- Some editors charge by word

- Some editors charge by hour

- Some editors charge by page

- Some editors offer a flat fee

My preference is to charge on a per-word basis, subject to seeing a sample of the novel. Because economies of scale come into play with longer projects, my per-word prices decrease as the project length increases.

For example, in 2020, I charge 7.5 pence per word for a 1,000-word sample edit, but the fee is 20% cheaper if I'm line editing a 5,000-word story and 50–60% cheaper if I'm dealing with an 80,000-word novel.

And so it depends on the parameters of the project.

Some editors charge more than me, some less, and some the same. My colleagues live all over the world, and fluctuations in the currency-exchange markets mean that comparisons will yield different results from day to day.

Some professional organizations suggest or report minimum hourly rates for the various levels of editing. They’re ballparks, nothing more, for reasons outlined below the table (fees correct as of July 2019).

|

Organization

|

Developmental editing rate per hour 2020

|

Copyediting rate per hour 2020

|

Proofreading rate per hour 2020

|

|

Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) (UK)

British pounds |

£34.00

|

£29.60

|

£25.40

|

|

Editorial Freelancers Association (USA)

US dollars |

US$45–55

|

US$30–60

|

US$30–35

|

|

€40+

|

€40

|

€25–35

|

|

|

National Union of Journalists (UK)

British pounds |

£30

|

£28

|

£24

|

Do these figures bear any relation to what individual editors charge? Sometimes but not always. Most organizations recognize that these reported prices don’t always reflect market conditions, and they’re right to do so. Many editors and proofreaders, myself included, aim for rates at least 30% higher.

Why? Because that’s what it takes for our businesses to be profitable. Editing and proofreading aren’t activities we do in our spare time. They're not side hustles. They’re careers that enable us to pay the bills. If we can’t meet our living costs, we become insolvent, just like any other business owner.

The problem with these ballparks is that they don’t reflect the speed at which an individual works, the complexity of each job, the time frame requested, or the editor’s circumstances.

An additional problem is that how these organizations define ‘proofreading’, ‘copyediting’ etc. might not reflect an author’s understanding of what the service involves, or what an editor has elected to include.

And then there’s the age-old issue of currency-exchange rates. What might seem a high rate to you one day could turn into something quite different the next, and not because the editor’s or the author’s life has changed, but because of Trump, or the Bank of England, or a hung parliament here, or a banking crisis there.

Bear in mind that independent editors are professional business owners, and just like any other business owner they are responsible for tax, insurance, sick pay, holiday pay, maternity/paternity entitlements, training and continued professional development, equipment, accounting, promotion, travelling expenses, pension provision, and other business overheads.

The table below gives you a rough idea of the speed at which an editor can work. Again, we’re dealing with ballpark ranges because the true speed will depend on the complexity of the project and how many hours a day the editor works.

|

Developmental editing speed

|

Copyediting speed

|

Proofreading speed

|

|

250–1,500 words per hour

|

1,000–2,500 words per hour

|

2,000–4,000 words per hour

|

|

80K-word novel:

53–320 hours or 2.5–12 weeks |

80K-word novel:

32–80 hours or 1.5–3.5 weeks |

80K-word novel:

20–40 hours or 1–2 weeks |

The figures in the table above represent a working day of around 5 hours of actual editing. Additional time will be spent on business administration, marketing and training.

Here’s how costs might begin to creep up. Imagine you ask your editor to copyedit your 80K-word novel. The editor estimates the job will take 50 hours, or two weeks. You need it in one. If you want to work with that editor, they’re going to have to work 10 hours a day, not 5. That means they have to pull 5 evenings on the trot in addition to their standard working day.

That evening work is when they spend time with their families, recharge their batteries, catch up with friends, support their dependents, carry out the weekly food shop, help their kids with the homework ... normal stuff that lots of people do.

If you want them to work during that time, it’s probably going to cost you more. For example, I charge triple my standard rate because my personal time is valuable to me – and to my child, who will need bribing!

The more the editor has to do, the longer the job will take and the higher the cost.

Some authors might not be aware of the different levels of editing and what each comprises. And editors don’t help – we define our services variously too!

For that reason, sometimes it makes sense to move away from the tangled terminology and focus on what each project needs to move it forward. An author might ask for a ‘proofread’ but the editor’s evaluation of the sample could indicate that a deeper level of intervention will be needed ... something more than a prepublication tidy-up.

I’ve copyedited novels whose authors had nailed narrative point of view at developmental editing stage, so I didn’t have to fix the problem. I’ve also copyedited novels in which POV had become confused. The sample-chapter evaluation highlighted the problem, and I had to adjust my fee to account for the additional complexity.

So, there we have it – 1,300 words that tell you not what editing and proofreading will cost, but what they might cost, depending on this, that, and everything else!

Here are some ideas for how to reduce your costs.

GENERAL MONEY-SAVING TIPS

- Do some pre-editing prep. Familiarize yourself with the different levels of editing so you do the right kind of editing at the right time. This booklet offers some guidance: Which Level of Editing Do You Need?

- Call on friends, family and writer buddies. It goes without saying that you want people on board who have the appropriate language and story-craft skills.

- Plan ahead to avoid premium fees for rush work. Start sourcing your editor several months before you need them – that way you can find the right editor to fit your needs and your budget. Here’s some guidance on how to find editorial professionals: How do I find a proofreader, copyeditor or developmental editor?

- Get quotes along with sample edits. These will enable you to compare how the work of several different editors, and what they're charging, makes you feel. Some editors charge a small fee for samples to cover the couple of hours they devote to the project.

SAVING MONEY ON DEVELOPMENTAL EDITING

Hone your story craft by reading books, taking writing courses, and joining writing groups through which you’ll be able to access fellow scribes! You can critique each other’s work and help each other with self-editing. I recommend these books:

- How Not to Write a Novel (Howard Mittelmark and Sandra Newman)

- The Magic of Fiction (Beth Hill)

- Write to be Published (Nicola Morgan)

Rather than commissioning a full developmental edit, you could pay for a critique or manuscript evaluation, or a mini edit. Those will help you to identify what works and what doesn’t so that you can make the adjustments yourself.

SAVING MONEY ON LINE EDITING

Hone your sentence-level mastery, again through books, courses and groups.

Some editors offer mini line edits for this stage of editing too. Here, the editor offers a line-by-line edit on several chapters and creates a report on the sentence-level problems with the text with recommendations for fixing them. The author can then refer to the mini line edit and mimic the sentence smoothing and tightening.

This kind of service is particularly useful for beginner authors who already know they’re prone to overwriting.

And I have a book you might find useful:

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level (Louise Harnby)

SAVING MONEY ON COPYEDITING

Learn how to use Word’s amazing onboard functionality, and macros and add-ins that flag up potential errors and inconsistencies. Here are some tools you can use:

- Watch this video. Use Word’s styles to format the various elements of your book consistently: Visit my Writing resources page and scroll down to this video: Self-editing your fiction in Word: How to use styles

- Download this booklet and use find/replace to locate and remove a whole bunch of nasties: The Author's Proofreading Companion

- Create a style sheet, so your editor doesn’t have to. This article includes a free style-sheet template: What's a style sheet and how do I create one? Help for indie authors

- Run a spell check

- Hunt out words you often confuse using this macro: Using proofreading macros: Highlighting confusables with CompareWordList

- Check the consistency of your proper nouns with this macro: A nifty little proofreading and editing macro: ProperNounAlyse

- Create a word list and check your spelling consistency using TextSTAT: How do I find spelling inconsistencies when proofreading and editing?

SAVING MONEY ON PROOFREADING

If you’re working on designed page proofs, there are a series of checks you can take your novel through.

- Download this checklist: How to check page proofs like a professional

- Proofreading is the final prepublication tidy-up, but if you’re working in Word you can also use the tools I listed in the copyediting section above.

- Check out this article of useful tools too: 10 ways to proofread your own writing

That’s it! I hope this article has given you a sense of what you might have to spend, and how you might be able to save during the editing process.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Some might tell us it’s a bum job, that we should run a mile. But is it? Should we? Would acceptance be a compromise or an opportunity?

Ideal is something to aim for but rarely what lands in our laps, especially in the start-up phase of a business.

- Perhaps the fee is a lot lower than we’d like or than some of our editing friends are earning.

- Perhaps the subject or genre on offer isn’t what we dreamed of when we set up our business.

- Perhaps the client is a publisher whereas we’d prefer to work with corporates.

- Perhaps the client wants the project completed in a time frame that means we’d have to work outside our preferred office hours.

The challenge of visibility

Being discoverable is a challenge for many new starters. Ideal projects are out there, but the editor or proofreader isn’t yet visible enough in the relevant spaces.

And even if they can be found, they might not yet have enough experience to instil the trust that leads to initial contact.

Broadly, it’s easier to get in front of publishers because we know who and where they are. They’re used to being contacted by us, too, so we can go direct and cold.

With non-publishers, it’s more difficult. Not every business, charity, school, indie author, or student wants an editor or understands the value we might bring to the table. Going direct and cold is a trickier proposition.

The issue of trust

It’s not just the mechanics of visibility. Emotion plays a part too, especially trust.

Non-publisher clients are more of a challenge. They might not be familiar with the different levels of editing.

Many will not have worked with a professional editor before.

Some – for example fiction writers – might be anxious about exposing their writing to someone they don’t know.

And for the inexperienced client, evaluating a good fit is more difficult.

In the start-up phase of business ownership, editors and proofreaders with less experience might therefore find it easier to acquire work with publishers than with non-publishers.

The choices on the business journey

So visibility and trust issues mean that new entrants to the field might not have the same breadth of choice as the more mature business owner.

It might mean deciding to accept work that isn’t ideal in the shorter term.

We could describe this as a compromise, but might it in fact be an opportunity?

Does the terminology matter?

I believe the terminology does matter because a compromise has negative connotations.

- A compromise implies a cost; an opportunity implies a benefit.

- A compromise implies a loss; an opportunity implies a win.

- A compromise puts us on the back foot; an opportunity pushes us forward.

Negatives leave us feeling dissatisfied, that we’ve been ripped off, that we’re not in control. We’re more likely to begrudge the choices we’ve made.

Positives are empowering. We’re more likely to see the choices we’ve made as rational and informed.

All of this might sound like a mindset game but there’s more to it than that. Decisions to accept work that isn’t ideal have measurable benefits.

However, we need a longer-term approach, and that can be tough for the new starter who’s surrounded by colleagues who are booked up months in advance with the work that they want.

If that sounds like you, think of your editing business like a garden.

The editorial garden

What you do this year is not separate from what will happen next year, or the year after, or five years down the road. All the choices you make on your business journey are connected.

If you don’t plant anything, however, nothing will spout, not now, not next year, not five years down the road. You will be treeless.

Is planting the seeds a compromise? I don’t think so. It’s the opportunity to grow a tree.

Should we begrudge all that work of watering and feeding for just a few green shoots in this season? Again, not to my mind. The effort we make now will bear fruit later.

Our businesses are the same.

A patch of my editorial garden

I thought it might be helpful to share a story about my own business journey. It’s about how I accepted work that was way below my ideal price point, and did so with pleasure, because I believed I’d be able to leverage it later.

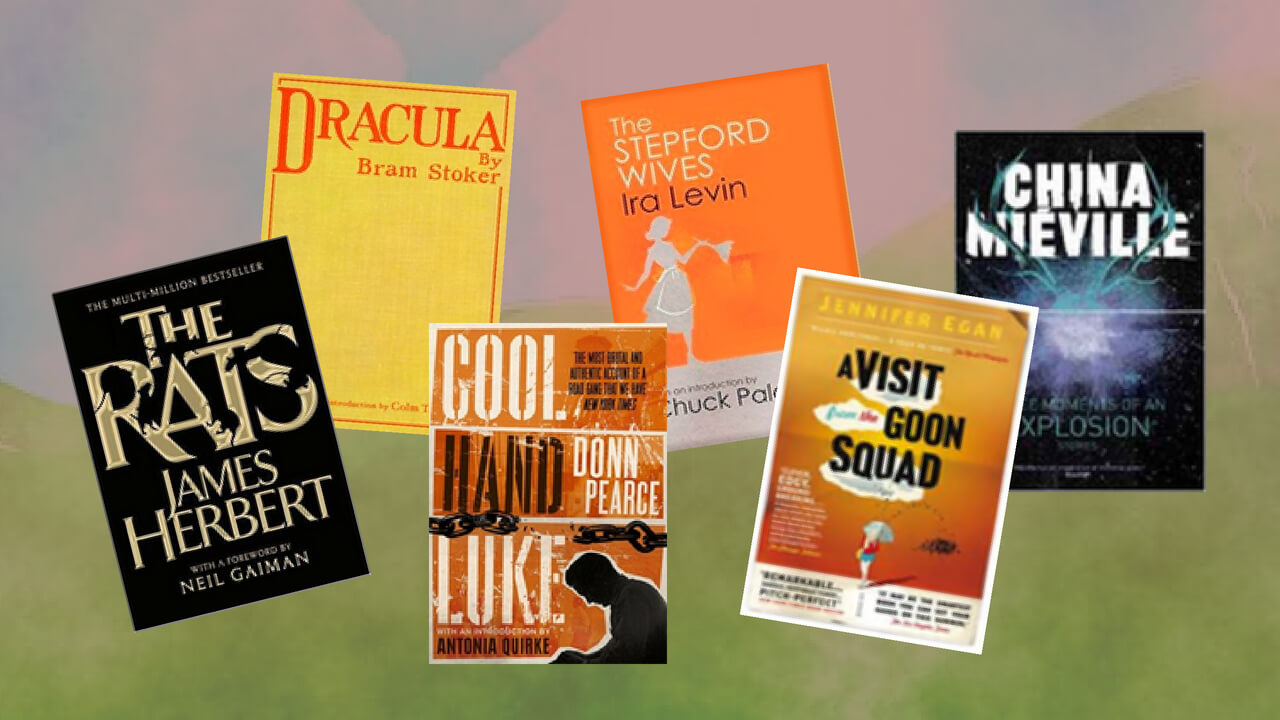

See these books?

- The Rats – this is a reissue of one of the UK’s most famous horror author’s first novels.

- Dracula – this is the centenary edition of possibly the most famous Gothic horror ever written.

- Then we have the Pulitzer-prize-winning A Visit from the Goon Squad.

- Three Moments of an Explosion is a short-story collection from one of the hottest ‘weird’ fiction talents in the market.

- And even if you haven’t read the books, you’ve probably heard of or seen the movie adaptations of The Stepford Wives and Cool Hand Luke.

These are some of the books I was commissioned by publishers to proofread a few years ago.

I proofread these books for about 13 quid an hour.

These days, I aim to earn between £35 and £40 per hour. It doesn’t always work out that way, but I hit my mark in the last financial year when I averaged out my annual project earnings. A few years ago, my aim was around the £30 mark.

Those books pictured above earned me less than half what I was aiming for. Did I compromise? Well, it depends how you look at it.

If, however, I decide that each decision I make can affect my choices down the road, that the walls around those individual decisions are permeable, it’s a different story. If I think that what I’m earning now is because of my decision to accept those proofreading projects, it’s a story of opportunity.

Authors make decisions to work with editors based on a whole host of factors, but the first step is deciding to get in touch in the belief that the person they’ve found feels like a good fit.

Back to trust

To take one example, those of us who edit fiction for self-publishers are asking those authors to put their novels into the hands of complete strangers.

Many of those authors have never worked with an independent editor. Some are anxious about the process of being edited. And for some, the editor’s might be only the second pair of eyes to read the text.

It’s a big ask that takes courage. And that’s where the trust comes in.

The editor who can instil trust quickly is more likely to compel authors to make the leap and hit the contact button.

And what better way to instil trust than offer a portfolio of mainstream published books written by big-name authors?

And that’s how I leveraged those half-my-ideal-fee books. They tell an anxious indie author that publishers of big-name books trusted me a few years ago. And that helps the author trust me now.

Those proofreading projects – and the £13 ph fees that came with them – encourage authors to contact me now, and trust that my £35–£40 ph line/copyediting fee is a worthwhile investment. And I know it’s true because they’ve told me it's so.

I didn’t compromise. I planted a seed. Now the tree has grown, and I’m able to harvest the fruit. I had to wait a few years but the decisions I made then affect the choices I have now.

And that’s how an editing garden grows.

Your choice

I’m a great believer in leveraging for future opportunity. It’s not everyone’s bag. It doesn’t fit with every editor or proofreader’s business model. And that’s fine.

I offer this not as THE way of thinking, but as one approach. It’s something that those at the beginning of their journey might like to consider if they are still building visibility, but struggling with the age-old rates debate!

As independent business owners, we are free to accept or decline fees from price-setting clients as we see fit. We are also free to propose rates that meet our individual needs, regardless of what our colleagues are offering.

If you’re offered work, can see the benefit of that work for your portfolio, but can’t stomach the price, decline. But if you wish to accept, even though others tell you the price is ‘too low’ or ‘unfair’, go for it.

The hive mind of the international editorial community is there to offer support and to share its wealth of experience, but no one knows your business and your needs better than you!

More resources

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Rate talk can trip us up if we're not careful.

And while it can be interesting to listen to colleagues’ opinions of whether a fee is low or high, their views might not be in any way useful for us because we need to make decisions based on our circumstances, not someone else’s.

Proofreader A lives in Oxnard, CA, USA. She tells her colleagues in an online forum that she’s accepted an offer from an agency to proofread 4,000 words for US$25.

The job is budgeted to take one hour. Some of her US colleagues say that the rate is unacceptably low; some even believe that she’s encouraging a race to the bottom by accepting such a fee from an organization whose rates are clearly unfair.

Meanwhile, Proofreader B, who lives in Manchester, UK, is reading the forum thread.

- It’s January 2017 and the exchange rate is 1 GBP = 1.22735 USD, which means that US$25 converts to £20.36.

- Roll back to early 2016, some months before the UK’s referendum on membership of the European Union. The exchange rate is 1 GBP = 1.468570 USD, which means that US$25 converts to £17.02.

- Let’s roll back one year earlier to 2015. The exchange rate is 1 GBP = 1.532750 USD, which means that US$25 converts to £16.31.

- Now let’s imagine instead we’re in January 2018. The pound has collapsed beyond even the worst expectations: 1 GBP = 0.8 USD, which means that US$25 converts to £31.25.

Proofreader B needs to earn a minimum of £20 an hour to meet her needs.

- If it’s January 2017, she thinks the agency’s rate is okay, but she already has enough clients filling her schedule who are paying that fee so she doesn’t feel compelled to jump through the hoops to get on board.

- If it’s January 2015 or 2016, she thinks the agency’s rate looks low because she has enough clients filling her schedule who’re paying a fee of a little over £20 per hour. The agency work therefore holds no appeal for her and she dismisses any thoughts of working with them.

- If it’s 2018, she’s already working out how she’ll word her email to the agency before she’s finished reading the thread. She thinks it’s a fantastic opportunity! £31.25 per hour? Nice!

Conversations that include blanket terms such as high and low therefore don’t help Proofreader B. Because the exchange rate fluctuates, so do her perceptions of whether a price is good or bad.

Proofreader C lives in Belfast, Northern Ireland. She tells her colleagues in an online forum that she’s accepted an offer from an agency to proofread 4,000 words for £16.

The job is budgeted to take one hour. Some of her colleagues say that the rate is unacceptably low; some even believe that she’s encouraging a race to the bottom by accepting such a fee from an organization whose rates are clearly unfair.

Meanwhile, Proofreader D, who lives just down the road from C, is reading the forum thread.

- She’s been working for a local supermarket, earning the UK’s legal national minimum wage of £7.50 per hour for people over 25 years of age. She lives at home with her parents so she’s able to survive on this.

- When not working, she’s used her spare time to take an intensive distance-learning proofreading course. She’s passed with distinction. Now she needs to find clients, acquire practical experience, build her portfolio, get some glowing testimonials – all valuable stuff that she’ll be able to sell on later to even better-paying clients.

- From her perspective, every hour she spends working for that agency she’ll be earning 113% more than if she was working in the supermarket. To her, the rate looks high.

- The agency is worth getting in contact with because it will offer her the opportunity to acquire some of that value-adding stuff mentioned above. She appreciates that it might not be a viable solution in the longer term, but her marketing is currently non-existent, which means her visibility to potential clients is non-existent. The agency will ameliorate the problem while she attends to making herself discoverable.

Proofreader E lives to the west in Strabane.

- She’s been professionally proofreading for eight years so her business is mature. She’s a marketing monster. Her website is highly visible on Google. She’s a member of the SfEP, EPANI and AFEPI, and advertises in their directories. Her portfolio’s stunning, her testimonials glowing. Anyone visiting those directories or her website will be in no doubt that she’s an experienced professional who can solve their problems.

- Her business has grown from strength to strength. She remembers what it was like to be in D’s shoes, but that’s not where she is any longer. These days, all her academic and business clients contact her direct or via her professional society directories. She no longer works for agencies, packagers or publishers, though she gladly took work from them in the early days of her business’s growth. Now, though, her own marketing strategy brings clients directly to her.

- Her average hourly rate is £32 and this supplements her partner’s income. The partner annually brings in 40% more than her, so her contribution means they have a comfortable lifestyle.

- From her perspective, every hour she spends working for that agency she’ll be earning 50% less than her current average. To her, the rate looks low.

- The agency is not worth a glance because she doesn’t need the client-acquisition value that it offers Proofreader D, and she can earn more from the large pot of clients who regularly get in contact and ask her to quote.

Proofreader F lives next door to E.

- She’s in the same boat as E except her partner was made redundant four months ago.

- The agency’s £16 won’t cut it. Proofreader E’s £32 won’t cut it. She needs £115.

- From her perspective, anything under £115 per hour is low because that’s what she requires to avoid moving to a smaller apartment, cancelling the pet insurance, junking the gym membership, throwing her Sky box into the trash, and selling the BMW. If things don't get better soon, she might have to give the pet away, or maybe the partner. She hasn't decided which yet, but the partner's food bills are higher! Seriously, though, if she's prepared to make some changes to her lifestyle, she can tweak her minimum hourly requirement accordingly.

So, conversations that include blanket terms such as high and low don’t help Proofreaders D, E and F either because although they’re all operating within the same geographical region and the same currency market, their circumstances are all very different.

Deciding what rate works for you

If you want to work out whether Agency X, Publisher Y or Packager Z’s rates are acceptable, you need to know what good, high, fair, low, poor and predatory mean to you based on your situation – not anyone else’s. The same thing applies to deciding what price to set with clients who come directly to you.

Consider the following:

- What’s the current exchange rate (if you’re dealing with a client from another country)?

- How fast can you proofread straightforward, middling and complex files? Are there efficiencies you can introduce to speed up the process? If you proofread straightforward work at 3,000 words per hour, a 6,000-word file with a fee attached to it of £30 will earn you £15 per hour. If you proofread straightforward work at 6,000 words per hour, a 6,000-word file with a fee attached to it of £30 will earn you £30 per hour.

- What are your outgoings? (Knowing this will help you calculate the minimum you need to earn to live.) If you are regularly offered a whopping £300 an hour, but your outgoings mean you need to earn £350 an hour, that fee is still too low for you (though most of your colleagues will be chomping at the bit for it!).

- How many hours do you have available for work? If you need to earn £600 per week, and you have 25 hours available, you’ll need to earn at least £24 per hour. If you only have 10 hours available, you’ll need to earn at least £60 per hour. Even if you have 50 hours available (meaning you could drop your minimum hourly rate to £12 per hour), could you sustain it? Only you know the answer to that.

- Are you in a position to source, or be found by, alternative clients who will pay you higher fees than those on offer by the agency, publisher or packager?

- If you are, is the volume of work on offer enough to ensure that your gross earnings from this work replace the income you would have earned from the agency, publisher or packager?

- Even if you have some lower-paying clients, do you have other better-paying clients who can offset the lower fees? I have some clients who pay premium rates for my services but the volume of work doesn’t fill my schedule. I could, however, choose to accept some work that pays less than my minimum requirements because the higher-paying clients’ fees would offset the deficit, rendering my average hourly rate one that’s still profitable for my business.

That data – as it applies to you, not your colleagues – will give you a useful initial benchmark with which to evaluate whether a fee is low or high.

Your colleagues’ opinions are interesting but your colleagues are not responsible for running your business or your home, so their opinions should not be used to determine whether you accept or decline work at a given price.

***

While I don’t believe that colleagues should be the sole determiners of the fees we accept or offer, I do think they’re the go-to people for many, many more types of information. See this post on the value of networking – both online and offline.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

What's a fair price for proofreading or editing?

One of my concerns when discussing rates is that the value of a particular client to the freelance editor or proofreader’s business is sometimes overlooked.

Terms such as ‘too low’ or ‘race to the bottom’ can be problematic because they’re used as if editorial business ownership is taking place in the now – as if the business, and the fees which that business owner accepts, are absolutes and somehow unrelated to what’s gone before or what will happen in the future.

I believe that business ownership is a journey – that the work I do, and the marketing I carry out to acquire that work, is fluid. The decisions I made and the actions I took three years ago affected the work I was doing and the fees I was charging/accepting at that time; but they ALSO affected the work I’m doing and the fees I’m charging/accepting now.

This fluidity means that the way we find value in a client extends beyond the rate.

Time for a case study to nail things down …

Case study: The packager and the proofreader

2012

Ellie’s a proofreader.

Work: She’s completed her training and become a member of her national editorial society. She’s technically excellent at her job, but she has no clients and very little experience of paid work.

Marketing: She has a website but the portfolio and testimonials pages are sparse. And, anyway, her SEO is, as yet, so undeveloped that she’s barely discoverable online. She gets in touch with a packager who regularly hires proofreaders who are members of her national professional society.

Clients: To the packager, she’s a great fit. She has the skills they want and she has the space in her schedule. To academics, students, businesses and independent authors searching for a proofreader, she’s invisible. Even if she were visible, she appears less experienced (less interesting, we might say) than other proofreaders touting their services.

Rates: The agency offers regular work, and the rate is £13.50 per hour. ‘That rate is woeful,’ says one of the more experienced colleagues in her network. ‘That’s so low it’s an insult,’ says another. ‘Accepting that is encouraging a race to the bottom,’ says yet another.

Action: Ellie accepts the work anyway – she has a cunning plan!

2014

Ellie’s still a proofreader.

Work: In the past two years, she’s done a book a month for that packager. Now, from that packager alone, she has 24 academic book titles in her portfolio – all of them published by international scholarly publishers, and some of them authored by big names in the academic community. She’s also contacted several academic presses whose rates are a little higher than the packager’s, but only by a few pounds.

Marketing: She’s been busy over the past two years.

- She published a smart portfolio on her website. Each of those titles, with their corresponding authors, contains rich keywords that in the longer term will make her website more discoverable to academics searching for editorial assistance in a particular field.

- She contacted several academic publishers (who don’t use the packager). They were impressed by her training and her experience – those 24 academic titles match their own publishing lists. They added her to their editorial freelancing lists and she now receives work from each of them every few months. Over the course of two years, she’s been able to add a further 27 titles to her portfolio.

- She requested testimonials from the packager and the publishers.

- She counted up her hours of experience, noted her professional training, and asked her referees if they’d support her application to upgrade her professional society membership. They said, ‘Of course!’ In two months’ time, she’ll meet the criteria to upgrade to a level of membership that entitles her to advertise in her professional society’s online directory – that’s more visibility. The directory enables her to link to her website – a superb SEO opportunity.

- She developed a number of value-adding tools for her website (checklists, advice, guidance, etc.). They’re targeted at clients to whom she’d like to be more visible in the future and with whom she’ll be able to command higher rates than she’s earning from the publishers and packager. She regularly shares this information using her social media platforms and professional networks – more SEO benefits, more visibility.

Clients: Two years ago, Ellie wasn’t discoverable to anyone but the packager and the publishers. Things have changed, though. It’s been a slow burn, but her down-the-road thinking has led to a larger number of direct hits on her website. There’s still a long way to go, but when clients visit her website now, they see the following:

- Experience – her portfolio page lists 51 books

- Trustworthiness – the pithy quotes from big-name presses inspire the viewer’s confidence in her ability

Rates: A few of the clients who’ve found her direct have accepted the rates she offered. These are sometimes as much as double the rate she’s earning from the publishers and packager. This inspires her to continue her marketing activities and increase her visibility to these client types so that she might shift her customer base as her business develops.

Ellie’s still not visible enough to fill her schedule with these better-paying clients. She continues to accept work from the publishers and the packagers. ‘Those rates are an insult to someone with your experience,’ cry some of her colleagues.

Action: Ellie accepts the work anyway – she’s not phasing out the publishers and the packager until she’s phased in enough higher-paying clients to replace the workflow and the income it provides.

2016

Ellie’s still a proofreader.

Work: Over the past two years, she gradually reduced the work for the packager, finally stopping it altogether at the end of 2015. She’s still taking some work from her early publisher clients, though much less than in 2012–14. That’s because she’s been working for four better-paying presses whose rates are what she’d define as ‘middle-of-the-road’, though nowhere near as high as the fees she can set when she works directly for authors and students.

Her increasing visibility has put her in a position where she receives several direct requests to quote per week. She’s noticed that some academic publishers are even asking their authors to source and pay for their own proofreading, so she’s glad she’s focused on making herself discoverable to these clients.

Marketing: Even though Ellie’s had a full schedule for several years, she’s continued to focus on what she wants down the road in terms of client types and income. The bread-and-butter work provided by the publishers and the packager have enabled her to concentrate large chunks of her marketing time on what she wants in the future without having to worry excessively about where today’s work will come from.

- Her portfolio is impressive. She’s added each new title and author to the page when she’s completed a project. That’s more rich keywords, plus her website is continually benefiting from having fresh content added (good for SEO).

- She’s advertised in several paid-for directories to increase her discoverability to businesses, students and independent academics.

- Her content marketing has continued – she’s added more resources that she believes will be of interest to her target clients.

- She’s upgraded her professional society membership status. Now her profile is visible via the organization’s website, which links to her own site. That’s more inbound/outbound links for her website, which is great SEO.

- She’s attended various workshops and conferences, and continues to network online. This relationship building has led to several referrals of work from colleagues whose own schedules were too full.

Clients: Ellie appears to clients as an experienced proofreader with professional qualifications. They think she’s on their wavelength because of the valuable resources she provides for free.

The fact that she’s worked for international academic publishing houses gives them confidence that she knows how to follow a brief and work on complex materials to a high standard. If she wasn’t capable, those presses wouldn’t have hired her repeatedly, would they?

Rates: Ellie no longer accepts work below £20 per hour, although she aims to earn an average hourly rate of £28. She can afford to make this decision because of the balance between her later-acquired, medium-paying publisher clients (who provide her with a stable workflow) and the higher-paying independent clients who contact her direct.

On an online forum, a new entrant to the field posts that she’s been offered proofreading work from a packager at a rate of £15 an hour. Does Ellie say, ‘That rate’s woeful. It’s an insult. Accepting it would be encouraging a race to the bottom’? Nope. She says, ‘Is there value in this work beyond the fee being offered?’ She goes further:

- Is the minimum you need to earn £15 or below? If it is …

- Will accepting work from that packager provide you with regular work so that you don’t have to spend as much time finding clients now?

- Because the packager is doing some of your project-acquisition on your behalf now, how much time will this free up for you to do marketing that will help you find better-paying clients later?

- Will accepting work from that packager provide you with projects that you can list on your website, thus providing rich keyword search terms that will make you visible to better-paying clients now and later?

- Will the work from that packager provide you with experience that you can sell on to better-paying clients now and later?

The business journey

Ellie’s business in 2012 looks different to Ellie’s business in 2016. Her client base has shifted, her income has shifted, the base price she’ll accept has shifted, her work stream has shifted and her visibility has shifted.

- It’s not just that the decisions she made in 2016 are different to those she made in 2012. Rather, the decisions she made in 2016 are founded on those she made in 2012.

- If she’d decided in 2012 that she wanted 2016’s offerings at the start of her career, she’d have struggled.

- It’s not that she wasn’t worth £X per hour back in 2012, but that she wasn’t in a position to be discoverable (or perhaps attractive) to those clients who were prepared to pay that price.

- Because she took a down-the-road approach – one that viewed her business as something that was moveable, something that could develop, grow and change – she was able to see opportunity and value in what was on offer back then.

There is value beyond the rate. Whether you take advantage of that value will depend on your particular circumstances, of course.

My advice to new starters is to be cautious when listening to the rates debate. It’s easy for seasoned professional editorial freelancers to advise against accepting this or that fee simply because they’re in a position to command better fees.

In fact, offering advice on what’s an acceptable price is almost impossible unless we understand an individual freelancer’s circumstances, requirements and access points to the industry.

Fees, like any other aspect of a business, need to be considered in the context of an overall business plan, and over a time frame that extends beyond the now.

More resources

- Guide: How to Develop a Pricing Strategy

- Blog: How to track the health of your editing business efficiently: The Editor's Affairs (TEA)

- Blog: How to convert requests to quote into paying work: Help for editors and proofreaders

- Free webinar: The different levels of editing

- Blog: How to minimize cancellations and non-payment for editing and proofreading services

- Blog: 'I want to be an editor – when will I start earning $?' and other unanswerable questions

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Taking annual action to increase income from freelance editorial work is simply good business practice.

Earnings need to keep up with cost-of-living increases else our editorial businesses could fail. Even if they don't fail, the decline in profitability could have a significant impact on our lifestyle and well-being.

What we earn is determined by the following:

- The fee we consent to when we’re in the position of being made an offer (from, say, a publisher, packager or agency). Here, we’re price-accepters.

- The fee we charge when we’re in the position of making an offer (to, say, an independent author, student or business). Here, we’re price-setters.

Increasing our earnings is not always straightforward, though. You or I might think our desired rate increase is entirely justified (for example, because of inflation). However, what you or I think is not the issue. Any change to a pricing model must consider the client’s response for the simple reason that the client might not be prepared to pay. Remember:

- When we’re price-setters, we’re within our rights to increase our fees. On the flip side, our clients are within their rights to decline the new price and walk away.

- When we’re price-accepters, our clients are within their rights to maintain their current fees (or even decrease them), while we’re within our rights to negotiate or decline the work and walk away.

Decisions about what to set or accept therefore need to be carefully planned.

Avoiding knee-jerk thinking

If a colleague states that they’ve decided to no longer edit for ‘low’ rates, by all means congratulate them on their business decision. Don’t assume, though, that their decision is the same one you should be making.

Before you impulsively follow their lead, ask yourself the following questions:

- What do they mean by ‘low’ rates? Is your definition of ‘low’ the same as theirs? You may think £25 an hour for editing is great but your colleague may think it’s unacceptable.

- Do they have a supporting income that enables them to implement their decision immediately with no harm to their lifestyle? Perhaps they have a partner who is the primary breadwinner, or maybe they’re lucky enough to have an independent income from a generous trust fund (we can all dream!). Put another way, your colleague might be able to afford to immediately decline £25 per hour on principle, whereas you’re responsible for all your monthly outgoings and aren’t in a position to bear the risk of earning zero pounds per hour until you have acquired a replacement client.

- Do they have a large and established client base in a sector that is known to be less price-sensitive than the sectors you work in? Perhaps their knowledge and specialist skills put them in the rare position of being able to name their price. You, on the other hand, might work in a more competitive generalist market where you’re easy to replace.

- Is their visibility so high that they’re confident they can replace lost clients with new customers who’ll pay their desired prices? Their marketing strategy is mature, whereas you’re still building your visibility and juggling feast and famine.

In other words, don’t feel compelled to decline work just because your colleagues deem what’s on offer as a bum deal. Their current circumstances might be very different from yours.

Not everyone can afford to be unemployed, and the choices available to a mature freelance-business owner may be very different from those on offer to the beginner.

Case study – the price-accepter