|

This post explains when and how to indent your narrative and dialogue according to publishing-industry convention.

The purpose of first-line indents

Each new paragraph signifies a change or shift of some sort ... perhaps a new idea, piece of action, thought or speaker, even a moderation or acceleration of pace. Still, the prose in all those paragraphs within a section is connected. Paragraph indents have two purposes in fiction:

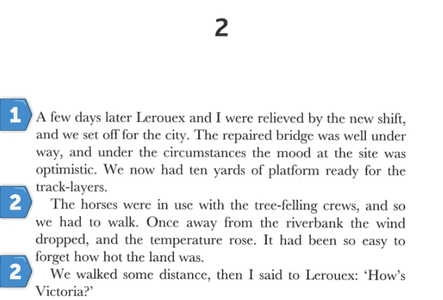

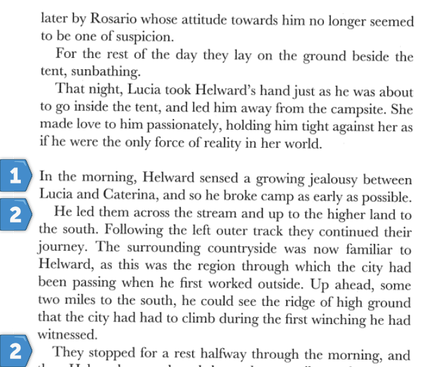

First lines in chapters and new sections Chapters and sections are bigger shifts: perhaps the viewpoint character changes, or there's a shift in timeline or location. To mark this bigger shift in a novel, it’s conventional not to indent the first line of text in a new chapter or a new section. You might hear editorial folks refer to this non-indented text as full out.

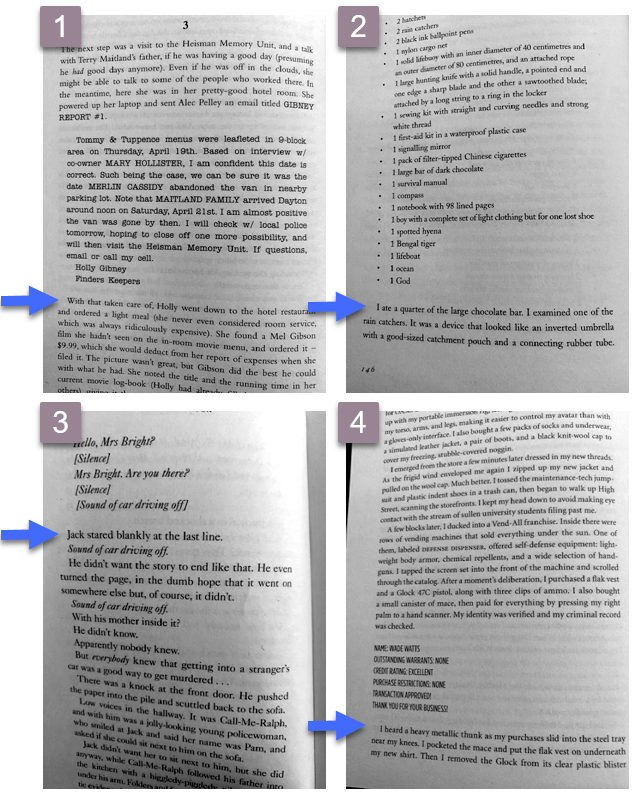

NARRATIVE LAYOUT The following example is taken from Part 5, Chapter 2, of Christopher Priest’s Inverted World (p. 287, 2010):

And here's an example from Part 2, Chapter 6, p. 147, which shows how the layout works the same after a section break:

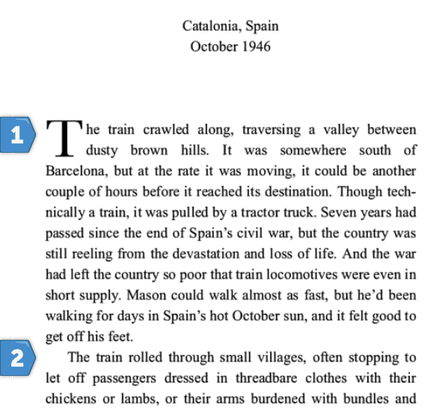

Even if an author chooses to include a design feature such as a dropped capital (sometimes called a drop cap), it's standard for that letter to be full out, as shown in the following example from To Kill a Devil (John A. Connell, p. 6, Nailhead Publishing, 2020):

DIALOGUE LAYOUT

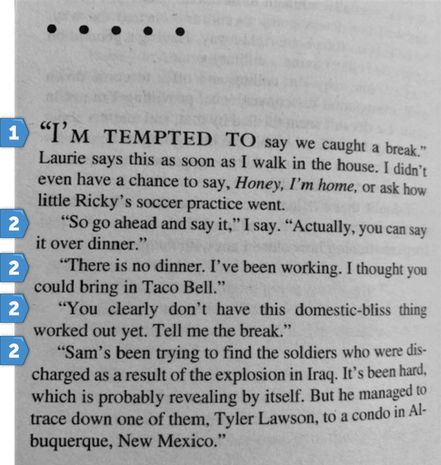

The same applies even if the chapter or section starts with dialogue, as in this excerpt from David Rosenfelt's Dog Tags (p. 192, Grand Central, 2010):

Body text: dialogue and narrative

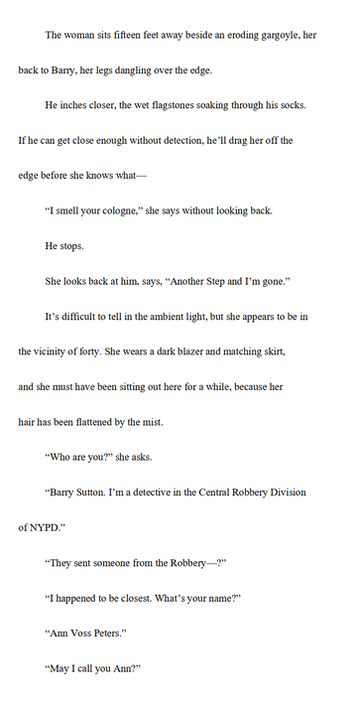

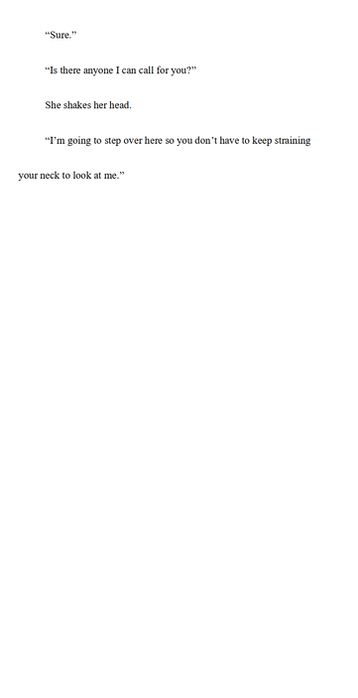

The example below from Blake Crouch's Recursion (p. 4, Macmillan, 2019) shows how the indentation works in the body text when there's a mixture of dialogue and narrative.

IMPACT OF LINE SPACING

Even if you've elected to set your book file with double line spacing (perhaps at the request of a publisher, agent or editor), the indentation convention applies. Here's the Recursion example again, tweaked to show what it would look like:

Indenting text that follows special elements

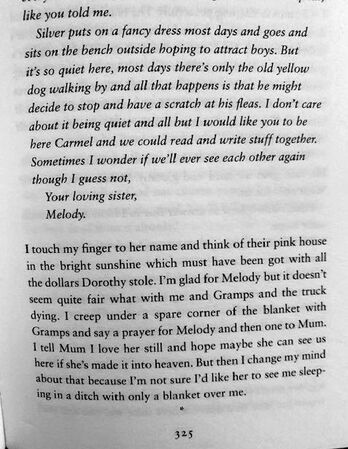

Your novel might include special elements such as letters, texts, reports, lists or newspaper articles. Authors can choose to set off these elements with wider line spacing, but how do we handle the text that comes after? Again, it's conventional to indent text that follows this content, regardless of whether it's narrative or dialogue. That's because of the connective function; the text is part of the same scene. Here are some examples from commercial fiction pulled from my bookshelves.

It's not the case that full-out text is never used, or can't be used, but fiction readers are used to conventions. When a paragraph isn't indented, they assume it's a new section, which creates a tiny disconnect.

That's what I think's happened in the example below from Kate Hamer's The Girl in the Red Coat (p. 325, Faber & Faber, 2015). Of course, it took me only a split second to work out that the narrator is referring to the preceding letter, but it's a split second that took me away from the story because I'd assumed I was looking at a section break. My preference would be to indent 'I touch my finger [...]' because that text is part of the scene, not a new section.

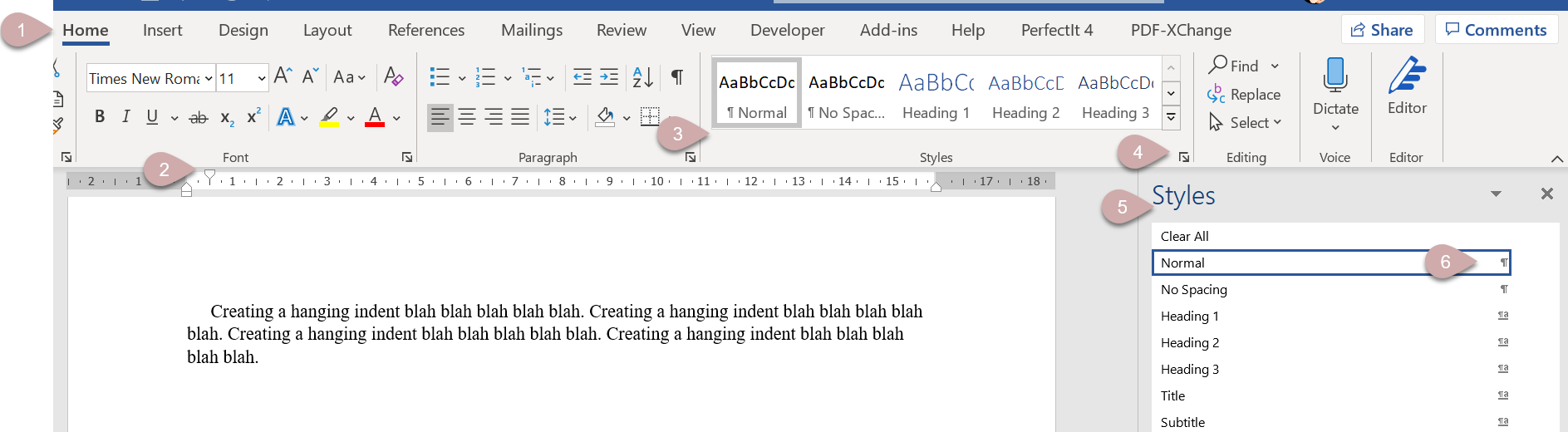

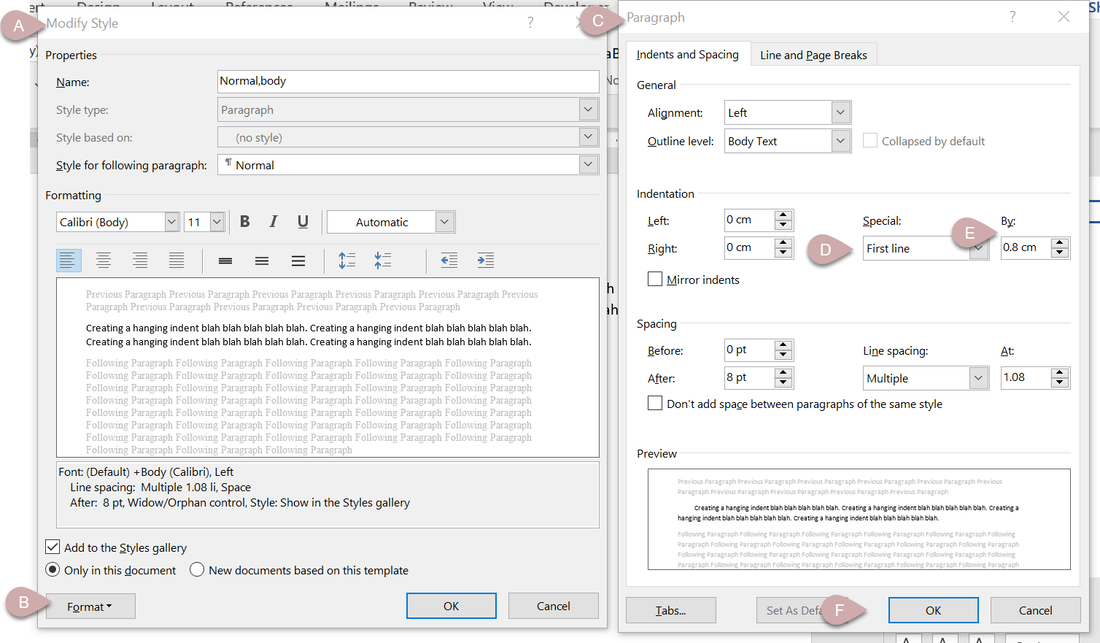

How to create a first-line indent in Word

Let's finish with some quick guidance on creating first-line indents. Avoid using spaces and tabs to create indents in Word. Instead, create proper indents. There are several ways to do this.

OR

Create a new style for your full-out paragraphs using the same tools.

If you need more assistance with creating styles, watch this free webinar. There's no sign-up; just click on the button and dig in.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

23 Comments

Non-viewpoint characters have emotions too. But how do we show them without head-hopping? The answer lies in mastering observable behaviour.

What is head-hopping?

When a reader can access the internal experiences (emotions, thoughts, memories) of more than one character in a chapter or section, head-hopping is usually in play. The exception is if you’re tackling the tricky beast that is omniscient narration. It’s difficult to pull off and rarely used in contemporary commercial fiction. Here’s an example of what head-hopping looks like on the page. Jack is the viewpoint character and the narration style is third-person limited.

The pebble bounces on the water seven, eight, no, nine times. Best ever, Jack thinks.

Pete weaves through the grass and slumps into a hollow in the dune. His brother’s whoop, the arc of his arm … just like Dad’s when they played skimming stones. Before the accident. Before the world changed. He shakes the memory from his head. Dwelling on that stuff never ends well. Jack turns away from the ocean, waves and calls for Pete to come down but the crashing surf swallows his words. Notice the following:

How to enter a non-viewpoint character’s space without dropping viewpoint There will be times when you want your reader to enter the emotional and physical space of a non-viewpoint character. Mastering observable behaviour – showing us what the viewpoint character can see, and their interpretation of that behaviour – is one solution that will enable you to hold viewpoint. Here’s a recast of the Jack/Pete scene:

The pebble bounces on the water seven, eight, no, nine times. Best ever, Jack thinks.

He whoops and turns his back to the ocean. Pete’s lumbering gait is unmistakable. He weaves through the grass on the dune and slumps into a hollow, mouth set in a hard line, neck hunched into his shoulders, complexion pasty. But he’s out; the sunlight’s on his face. It’s the first time since a month of whenevers. Skimming stones was something they did with Dad. Before the accident. Before the world changed. Jack shakes the memory from his head. Dwelling on that stuff never ends well. He waves, calls for his brother to come down but the crashing surf swallows his words. Notice the following:

Mastering observation

Mastering observation enables writers to retain viewpoint but not be restricted by it. Think about how non-viewpoint characters will move in a way that reflects their internal experience, or what they will look like. Here are a few examples:

Summing up

If you’re writing in a third-person limited narration style, consider what the viewpoint character already knows, what they can observe in relation to a non-viewpoint character, and what they could infer from those observations. That will determine what they can report. What they report can still allow readers to access the internal experience of the non-viewpoint character through a back door. And while that report will be biased, it will be immersive.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Himself, herself, myself, themself ... check the usage of pronouns in your fiction. You might just be overworking them, such that you’re stating the obvious, modifying the pace, and reducing tension.

Questionable usage

Reflexive pronouns can act as double tells by stating the obvious, and mar pace and tension. Stating the obvious

When it comes to internal musings, authors can ditch the reflexive pronouns. Thoughts take place inside a person’s head and, by definition, are offered only for the thinker – unless there’s telepathy going on in the novel! Moderating pace and reducing tension

These are high-tension scenes. Max is in a shoot-out; Ali’s escaping danger. Every word stretches out the sentence. And as the sentence length loosens, so does the tension. Look what happens when we remove the pronouns:

The sentences shorten, the pace increases – and so does the tension.

Usage that works

We shouldn’t omit all -self pronouns. There are occasions when a sentence works better with them. Sometimes they’re essential. Clarity In some cases, the pronoun is necessary for clarity. The reader can’t be sure of what the verb’s object is without it. In the examples below, removing the pronouns could leave the reader with questions: Ashamed of what? A promise to whom? Stop what? Consider whom an expert?

Emphasis The pronoun can be used to emphasize the person being discussed. Omission would leave the sentence grammatically intact but change the mood and pacing. In this case, it’s a judgement call on the author’s part.

Sense Some sentences don’t make grammatical sense without a reflexive pronoun. Remove them and the writing leaves more than questions: it’s unreadable.

Reflexive pronouns: mood versus clutter

At the top of this post, I offered examples of how -self pronouns can reduce tension. There will be occasions when an author wants to do exactly that.

There’s a more staccato feel to the second version above that might jar if the author’s seeking a contemplative mood. Still, too much self-ing can make even a stress-free scene overly wordy so it’s always worth thinking about whether a leaner version would be more immersive and get the reader from A to B faster. In the first version of the triplets that follow, the pronouns introduce a chilled-out sense of laissez-faire to the movement. In the second I’ve omitted them. And in the third, I’ve ditched the mundane movement and focused on the essential beat.

It’s always worth an author spending a little time on thinking about how much micromanagement of a scene is necessary. Will the reader care about the chair discovery, or that Maxie had a hot drink while they were reading the letter, or that the protagonist was no longer on the sofa when she called Mel? Perhaps. If that stuff’s central to driving the novel forward, to reflecting mood, to grounding the character in the environment, the pronoun and the stage direction might be necessary. If it’s clutter that can be removed without damaging reader engagement, lean up the scene! Summing up Use reflexive pronouns when they’re necessary for clarity, sense and emphasis. Otherwise, consider leaner prose that focuses on what the reader needs to know to move forward in the story.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

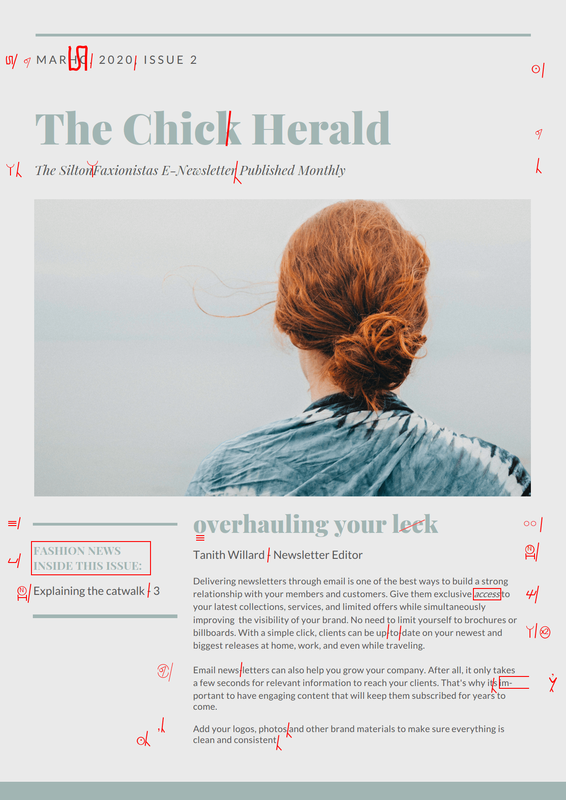

Want to mark up greyscale and colour PDFs digitally? My upgraded BSI-compliant stamps now have fully transparent backgrounds and are completely free to download.

Many of my colleagues have been using these PDF proofreading stamps for years. And they worked fine as long as the markup area was white.

However, when it came to annotating tinted elements, the markup looked messy. That's because when I created the stamps back in 2012 – all 113 of them – I took design shortcuts that meant some stamps didn’t have transparent backgrounds. I knew some of the stamps weren’t perfect but creating three sets had been backbreaking work and, if I'm honest, I couldn’t face returning to the project and redrawing them. Eight years on, I decided to review the position. And, in fact, amending the problem stamps turned out to be not nearly as onerous a task as I’d expected. What the new stamps look like Below is a mock-up to show you the improvements. All the stamps now have transparent backgrounds, which means you can place them anywhere on the PDF page regardless of whether you’re marking up on white space, tinted boxes or photographs.

Advantages of using stamps

If you're happy with your PDF editor's onboard annotation tools, great; carry on using them. However, some proofreaders choose to add these stamps to their editing toolbox for the following reasons:

Click on the button below to access the updated stamps. They come in red, blue and black, and can be with with Windows and Mac OS.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses. |

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed