|

In this episode of The Editing Podcast, Denise and Louise discuss how to use exclamation marks, and why more than one is too many.

Click to listen to Season 4, Episode 2

Listen to find out more about:

Editing bites

Music credit ‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

7 Comments

In this episode of The Editing Podcast, Louise and Denise discuss the grammar police, how to manage them, and why they're nothing to do with professional editing.

Click to listen to Season 4, Episode 1

Listen to find out more about:

Editing bites

Music credit ‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Not sure if contractions are a good fit for your fiction’s dialogue? Here’s why they (nearly always) work.

Next time you’re in the pub with friends, at the dinner table with your family, or travelling on the bus, do a bit of people-listening. They’ll speak with contractions: you’re, they’re, I’m, don’t, hadn’t, can’t and so on.

Contractions are a normal part of speech. They help us communicate faster and improve the flow of a sentence. Watch the following videos and listen to the spoken words. They feature people with very different backgrounds, sharing different stories, and in situations that demand varying levels of formality.

The people talking have one thing in common: they use contractions when they speak ... most (though not all) of the time. That’s why when we want to write natural dialogue – dialogue that flows with the ease of real-life speech – contractions work. How contractions affect the flow of dialogue Take a look at this excerpt from No Dominion by Louise Welsh (Kindle edition, John Murray, 2017). Here’s the contraction-free recast. It reads awkwardly, and leaves us unconvinced that what’s in our mind’s ear bears any relation to what we would have heard had this been real speech. And that means we’re questioning the authenticity of the story rather than immersing ourselves in it.

He settled himself on the chair. ‘I do not know where you have just come from, but round here nothing is odd.’ He emphasised the word, making it sound absurd. ‘People come, people go. Sometimes they need something. Sometimes they have got something I need. We trade and they go on their way.’

Contractions and genre Some authors avoid contractions because of the genre they’re writing in. You’re more likely to see this in historical fiction than contemporary commercial fiction but it’s not strictly genre-specific and is more an issue of authorial style. Here’s an excerpt from a contemporary psychological mystery, The Wych Elm (Penguin, 2019, p. 71). Tana French uses contractions in the narrative and dialogue. The speech sounds natural; the narrative that frames it is informal. Compare this with Our Mutual Friend (Wordsworth Editions, 1997, p. 235). Dickens, writing literary fiction in the 1860s, still uses contractions in dialogue, although he avoids them in his more formal but wickedly tart narrative.

Now look at Ambrose Parry’s The Way of All Flesh (Canongate Books, 2018). The authors (Parry is the pseudonym used by Chris Brookmyre and Marisa Haetzman) don’t avoid contractions completely but the sparing usage does give the dialogue a more archaic feel. Here’s an excerpt from p. 259. I doubt anyone would be surprised when I say that the setting is 1847. And so it works. However, if the novel were set in 2019, there’d be a problem. We’d consider those characters unrealistically pompous and the dialogue overblown. Contractions, pace and voice The decision to use or avoid contractions is a tool that authors can use to deepen character voice. Specific contracted forms might enable readers to imagine regional accents, social status and personality traits such as pomposity. P.G. Wodehouse is a master of dialogue. Bertie Wooster is a wealthy young idler from the 1920s. Jeeves is his savvy valet. The dialogue between the two pops off the page and Wodehouse uses or avoids contractions to make the characters’ voices distinct.

You can see it in action in The Inimitable Jeeves (Kindle version, Aegitus, 2019).

In Oliver Twist (Wordsworth Classics, 1992, p. 8), Dickens contracts is not (ain’t) and them (’em) to indicate the low social standing of Mrs Mann, who runs a workhouse into which orphaned children are farmed.

Contractions and their impact on stress and tone You can use or omit contractions in order to force where the stress falls in a sentence. Compare the following:

By not using a contraction in the second example, the stress on ‘cannot’ is harder. The change is subtle but evident. With can’t the mood is one of disbelief tempered with a whining tone; with cannot the disbelief remains but the tone is angry. Here’s another excerpt from The Way of All Flesh (p. 140). The speaker is a surgeon, Dr Ziegler.

Parry’s dialogue doesn’t just evoke a historical setting. The style of the speech affects the tone too. The voice is compassionate, the mood stoic. However, the lack of contractions renders the tone precise and careful. On p. 142, Raven – a medical student turned sleuth – talks with the matron about medical charlatanry:

Using there is forces the stress on is, and in consequence the tone is resigned. With there’s the stress would have fallen on worse, and we might have assumed a more conspiratorial tone, as if she were about to divulge a secret. Contractions and narration style If you’re wondering whether to reserve your contractions for dialogue only, consider who the narrator is. Let’s revisit Tana French (p. 1). The viewpoint character is a privileged man called Toby, the setting contemporary Dublin. What’s key here is that the narration viewpoint style is first person. It is Toby who reports the events of the mystery; the narrative voice belongs to him. His narration register is therefore the same as his dialogue register – relaxed, colloquial – and the author, accordingly, retains the contractions in the narrative. For sections written in third-person limited, the narrative voice would likely mirror the viewpoint character’s style of speaking. However, if you shift to a third-person objective viewpoint, where the distance between the characters and the readers is greater, the narrative might handle contractions differently to dialogue. It's a style choice you'll have to make. Guidance from Chicago Still a little nervous? Here’s some sensible advice from The Chicago Manual of Style, section 5.105:

‘Most types of writing benefit from the use of contractions. If used thoughtfully, contractions in prose sound natural and relaxed and make reading more enjoyable. Be-verbs and most of the auxiliary verbs are contracted when followed by not: are not–aren’t, was not–wasn’t, cannot–can’t, could not–couldn’t, do not–don’t, and so on. A few, such as ought not–oughtn’t, look or sound awkward and are best avoided. Pronouns can be contracted with auxiliaries, with forms of have, and with some be-verbs. Think before using one of the less common contractions, which often don’t work well in prose, except perhaps in dialogue or quotations.’

Evaluate the sound Here are three ways to help you evaluate the effectiveness of contracted or contracted-free dialogue: 1. Read the dialogue aloud: Is it difficult or awkward to say it? Does it sound unnatural to your ear? Do you stumble? Does it feel laboured, like you’re forcing the flow? If so, recast it with contractions. If the revised version is smoother, and the integrity of the setting is retained, go with the contracted forms. 2. Ask someone else to read the dialogue: Objectivity is almost impossible when it comes to our own writing. If the plan is that no one but you will ever read your book, write your dialogue the way you want to write it and leave it at that. If, however, you’re writing for readers too, and want to give them the best experience possible, fresh eyes (and ears) will serve you well. You could even give your readers two versions of the dialogue sample – one with contractions and one without – and ask them which flows better and reads most naturally. 3. Head for YouTube: Dig out examples of speech by people whose backgrounds, environments and historical settings are similar to those of your characters. Watching characters in action will give you confidence to place on the page what can be heard from the mouths of those on the screen. Summing up Whether to use contractions or not in dialogue is a style choice. There are no rules. However, a style choice that renders dialogue stilted and unrealistic is not good dialogue.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with independent authors of commercial fiction, particularly crime, thriller and mystery writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Fresh eyes on a piece of writing is ideal. Sometimes, however, the turnaround time for publication precludes it. Other times, the return on investment just won’t justify the cost of hiring a professional proofreader, especially when shorter-form content’s in play. Good enough has to be enough.

Here are 10 ideas to help you minimize errors and inconsistencies.

Checking our own writing rarely produces the same level of quality as a fresh pair of eyes. We see what we think is on the page, not what is on the page. That's because we're so close to the content.

I'm a professional editor and I know that when I don't pass on my blog posts to one of my colleagues there are more likely to be mistakes. It's not that I don't know my craft but that I'm wearing a writer's hat. Sometimes, getting pro help isn't an option. So what can you do to minimize errors and inconsistencies? Here are 10 tips.

Style guides help you keep track of your preferences, including hyphenation, capitalization, proper-noun spelling, figures and measurements, time and date format.

2. Use a page-proofs checklist

This pro-proofreading checklist (free when you sign up to The Editorial Letter) helps you spot and identify layout problems in designed page proofs (hard copy or PDF). It’s based on the house guidelines provided by the many mainstream publishers I've worked for.

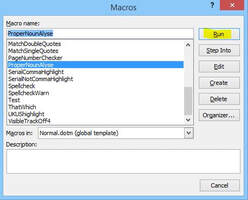

3. Run PerfectIt

PerfectIt is affordable software that takes the headache out of consistency checking. And because it’s customizable, it will help you enforce your style preferences and save you time. It’s a must-have tool for writers and pro editors.

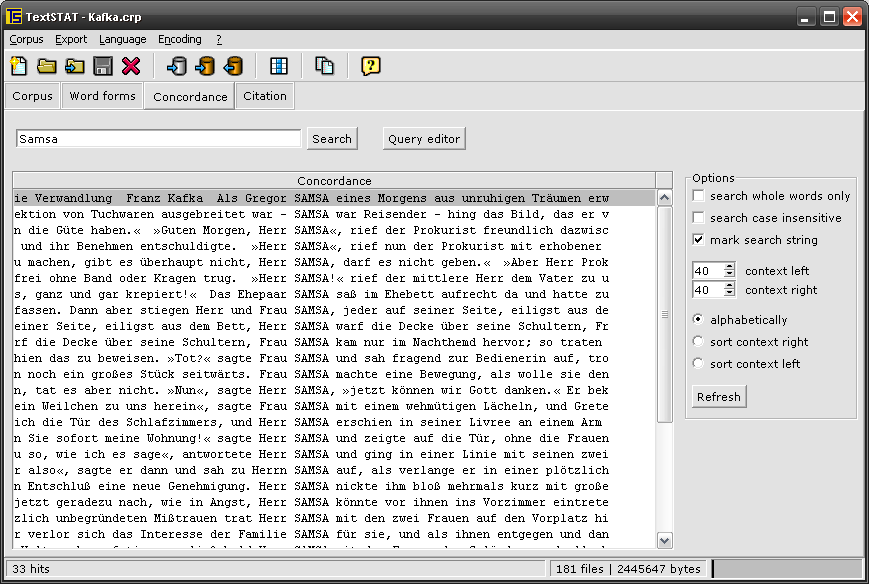

4. Use find-and-replace in Word

Microsoft Word’s onboard find-and-replace tool enables you to locate and fix problems in your document quickly. This free ebooklet, The Author’s Proofreading Companion, includes a range of handy strings and wildcard searches.

5. Set up styles in Word

Word's styles palette ensures the different elements of your text are formatted consistently. This tutorial shows you how to set up, assign and amend styles. It'll save you heaps of time whether you're working on business documents, web copy, short stories or novels.

6. Trade with a colleague

If you want fresh eyes but budget's an issue, swap quality-control checking with a colleague or friend in the same position. Pick someone who has a strong command of language, spelling and grammar.

Even if they're not a professional editor, they're wearing the hat of the reader, not the originator, and that means they'll spot things you missed. 7. Tools that locate inconsistent spelling

Here are 2 tools to help you locate inconsistent spelling:

8. Run The Bookalyser

The Bookalyser analyses a text for inconsistencies, errors and poor style: 70 different tests across 17 report areas in about 20 seconds, for up to 200,000 words at once. It works on fiction and non-fiction, and for British and American English.

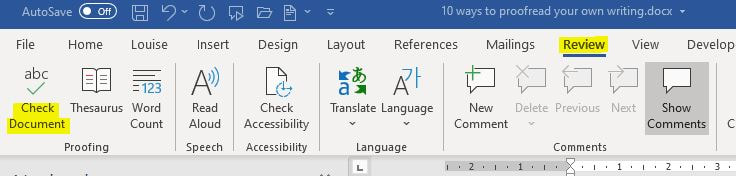

9. Run Word’s onboard Check Document tool

Microsoft Word has an onboard document-checking tool that flags up potential spelling and grammar problems. It's not foolproof (no software is) but it's a second pair of digital eyes that's available at a click.

Go to the ribbon, click on the Review tab, and select the Check Document button. 10. Read it out loud

Read the text out loud. Your brain works faster than your mouth and you might well spot missing words, grammar flops and problems with sentence flow when you turn the written word into the spoken word!

Word also has an onboard narration tool that can do the speaking for you. There’s a tutorial here: ‘Hear text read aloud with Narrator’.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Want to write great editorial reports, demonstrate excellence, and make your authors happy? How to Write the Perfect Fiction Editorial Report is for you.

Fiction editing isn't just about amending a book file or suggesting changes in comments boxes. It's also about communicating the why of our editing practice.

A high-quality, accessible report is as important as the book edit itself. Join me to find out how to do it.

This is an online multimedia course. Your kit includes:

And if you're already a member of my Facebook group, check out the notification there for your exclusive group-member discount.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with independent authors of commercial fiction, particularly crime, thriller and mystery writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses. |

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed