|

Every professional editor and proofreader wants to attract best-fit clients who are prepared to commit to a contract of editorial services. For the most part, bookings go smoothly – cancellations, delays, and failures to pay are unusual. Still, editorial business owners need to protect themselves ... just in case.

This article doesn’t seek to offer you a model contract or set of terms and conditions (T&Cs), though you’re welcome to look at mine for inspiration: Terms and conditions.

Instead, I want to explore some ideas about how to develop your spidey sense, and use language and tools that will repel those who’d let you down. What does ‘delay’ mean to you? The concept of the delay is nonsense to an editorial business owner. If a client asks you to proofread a book, tells you the proofs will arrive with you on 10 May, and requests return of the marked-up proofs a week later, and you agree to take on the job, those are the terms: proofread to start 10 May; delivery 7 days later. You’ll schedule the project accordingly, and will decline to work for anyone else from 10–17 May. If two weeks ahead of the start date you’re told ‘there’ll be a delay’, you’ll likely have no work for 10–17 May unless you can fill that space at the last minute. Moreover, you will be booked for another project during the period when the project will become available. To my mind, that’s not a delay. You can’t magic additional hours out of thin air. That’s a cancellation of the project terms that were agreed to by both parties.

Make sure your T&Cs reflect this. Don’t use the language of delay if it means nothing to you. Have a cancellation policy and make it clear that confirmed bookings are for an agreed time frame, and that failure to meet the agreed date will invoke that cancellation policy.

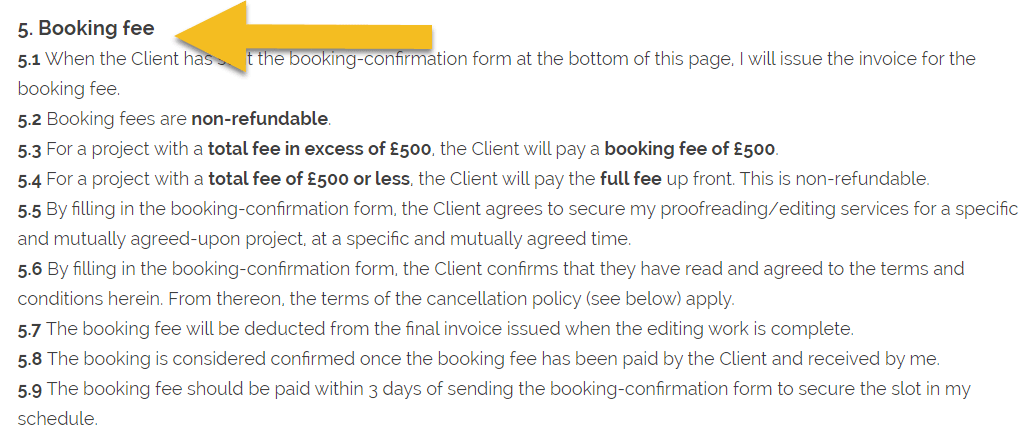

You might decide not to invoke it as a courtesy, but having it could reduce the likelihood of having to make the decision. Is ‘deposit’ a strong enough term? The word ‘deposit’ should be strong enough as long as the refund terms are clear. Still, you might want to couch your language along the lines of what editor and book coach Lisa Poisso calls ‘real money’. I don’t refer to deposits in my terms and conditions. I call them booking fees. A fee is a payment. It’s the language of money. ‘Deposit’ as a noun has a broader mass-of-material meaning; as a verb it means to place something somewhere. Maybe, for some people, it has a softer feel to it.

Of course, anyone required to pay a deposit knows full well that the financial definition is being referred to. Nevertheless, using the language of money – a fee – might well encourage time-wasters to think twice.

The following might also work for you:

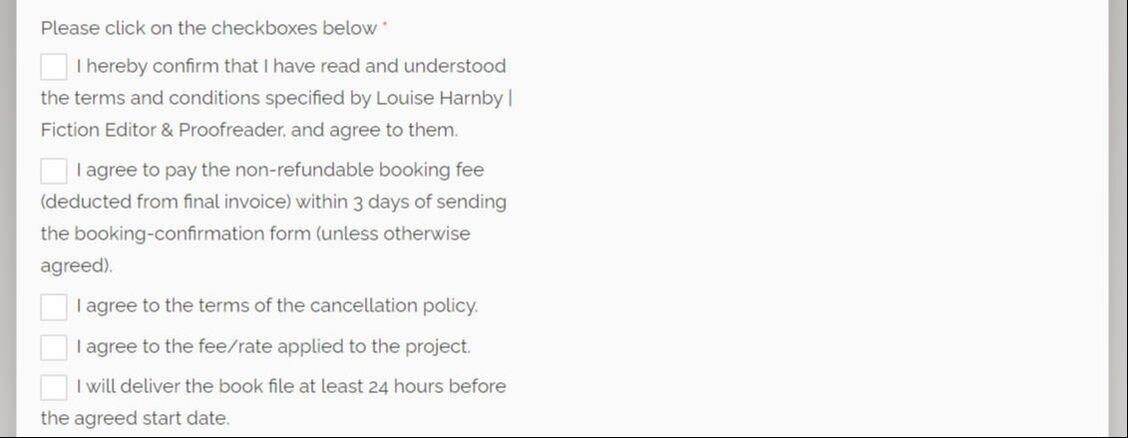

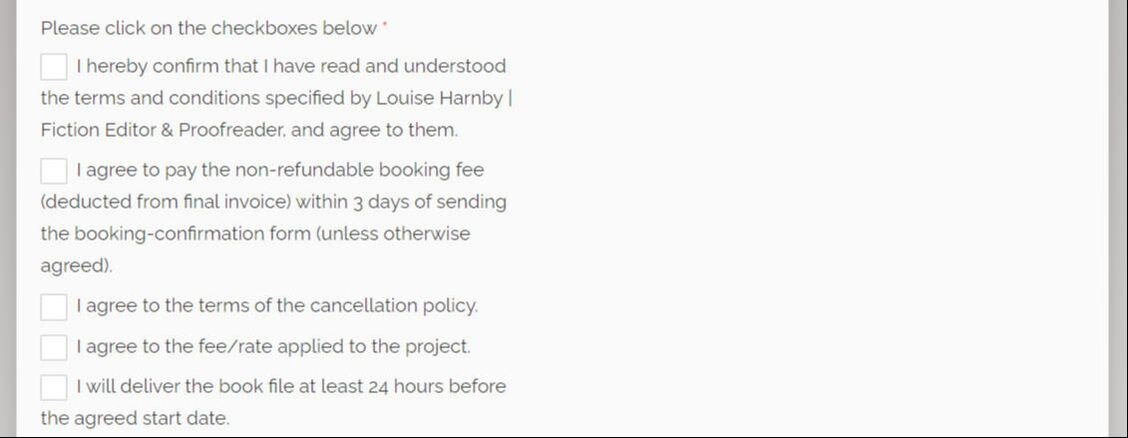

What you charge upfront is up to you. Some editors charge a 50% booking fee rather than a flat rate. Some require one third to secure the booking, another third just before editing starts, and the remaining third upon completion of the project. You can define your own model. Do you have a booking form? You and a client can agree to your providing editorial services via email, and emails count contractually. But how about requiring a specific additional action, one that reinforces a sense of commitment? Asking someone to fill in a booking form that confirms they have read, understood and agreed to your terms and conditions, including your booking fee and your cancellation policy, means they have to make a proactive decision to commit. When it comes to filling in a form and ticking boxes, a non-committed client is less likely to feel comfortable than a good-fit one because it feels more formal. You can create a PDF booking form that you’ll email manually, or create the form on your website. My choice is the latter. I include it below my T&Cs. That way, the booking and the terms are closely linked. Here’s a screenshot of mine. Notice the boxes that must be checked in order to confirm the booking.

Is ‘booking form’ a strong enough term?

Even if someone is prepared to fill in a form and check some boxes, agreeing to a contract might make them think twice. That has a more legally binding feel about it; it’s more formal. And it might be the thing that repels someone who’s going to let you down. My T&Cs state that the booking-confirmation form is an agreement to the contract of services between me and the client, and the phrase ‘Contract of services agreement’ in the heading is what appears when they click on the booking-confirmation form button.

Are your terms and conditions detailed enough?

In the main, your website should be client-focused. It should make the client feel that you understand their problems, are able to deliver solutions, and understand what the impact of your solutions will be. Your brand voice should sing out loud. In my case, for example, that means using a gentle, nurturing tone. However, when it comes to your terms and conditions, forget all the touchy-feely stuff – this is where you and the client get down to business. It’s in everyone’s interests to know what’s what. That might mean that your T&Cs are rather dull and boring. No matter. It’s the one place on your website where you’re allowed to be dull and boring! I feel like chewing my own arm off when I read my T&Cs but I don’t want any of my clients in doubt about what I’m offering and what they’re getting. Think about the following:

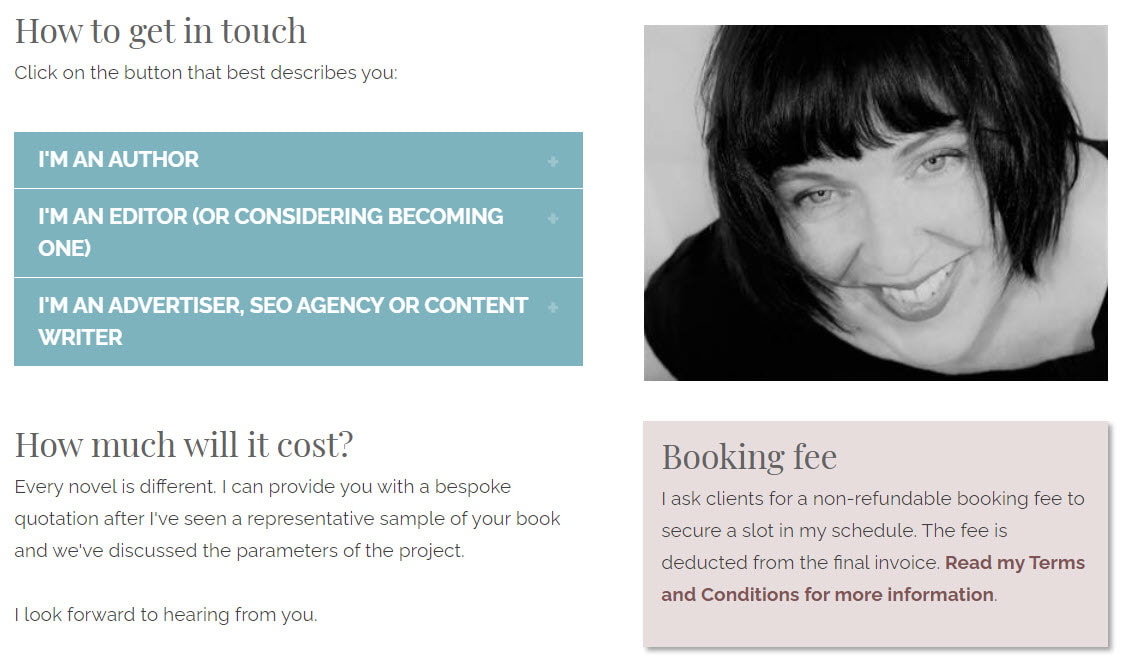

A non-committed client will be repelled if your terms put them at risk. A good-fit client will feel reassured that they’re dealing with a fellow professional who takes the editing work as seriously as they do. Are the basics front and centre? Many editors place links to the detailed contractual stuff in their website’s footer, which means the T&Cs are almost invisible. Even a good-fit client probably won’t see or read your T&Cs during their initial search for editorial services. That’s the case on my website. If it’s the same for you, consider placing the basics front and centre. I’ve created a box on my contact page that spells out the non-refundable booking fee I charge.

Will it put off some potential clients? Absolutely. But if someone can’t afford that booking fee or doesn’t dare take the risk of making a payment because they’re unsure whether they’ll honour the contract, they’re not the right client for me.

Spotting red flags Developing your spidey sense can reduce the likelihood of becoming entangled with those who’ll back out of confirmed bookings or fail to pay.

Though there’s no foolproof way to protect yourself from non-committed clients, there are red flags you can look out for:

Summing up I hope these tips help you avoid non-committed clients and safeguard your business. Even if you implement some of my ideas, there are no guarantees unless you ask for 100% of your fee upfront. However, rest assured that most clients are honest, committed and trustworthy individuals who are a pleasure to work with. As for those who blow you out, a few are scoundrels. Others aren’t but are thoughtless and haven’t taken the time to understand the emotional and financial impact of cancellations and non-payment. Others have got cold feet. And some have been struck by unusual or extraordinary circumstances like bereavement. Most don’t mean to cause distress or place editors in financial hardship, even though those are two very real potential outcomes. By using real-money language and action-driving tools, we can build stronger bonds of trust with those who are serious about working with us, and repel most of those who aren’t. More resources

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

12 Comments

Editors on the Blog is a monthly column curating some of the best posts from the editing community – articles written by editors and proofreaders for colleagues and clients alike.

My thanks to this month's contributors!

THE BUSINESS OF EDITING

CLIENT FOCUS: BUSINESS AND OTHER NON-FICTION

CLIENT FOCUS: FICTION

EDITING IN PRACTICE

LANGUAGE MATTERS

To include your article in next month's edition of Editors on the Blog, click on the button below. The deadline is 10 September 2018.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with independent authors of commercial fiction, particularly crime, thriller and mystery writers. She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Society for Editors and Proofreaders (SfEP), a member of ACES, and a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi). Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn.

Here are 10 tips to help you prepare the way for editing and proofreading fiction for independent authors and self-publishers.

If your editorial business is relatively new and you’re keen to specialize in fiction editing, there are some core issues that are worth considering. Some of these certainly apply to other specialisms, but fiction does bring its own joys and challenges.

1. Untangle the terminologyYou'll need to be sensitive to the fact that your clients may not be familiar with conventional editorial workflows or the terms we use to describe them! Clarify what the client expects, especially when using terms like ‘proofreading’ and 'editing'.

2. Discuss the revision extentClarify the extent of revision required before you agree a price.

3. Manage expectationsFind out how many stages of professional editing the file has already been through.

4. Put the client first – it’s all about the authorWhat’s required according to the editorial pro and what’s desired by the client (owing to budget or some other factor) could well be two very different things.

5. Be a champion of solutionsThe authors we’re working with are at different stages of writing-craft development. Some are complete beginners, some are emerging, others are developing and yet others are seasoned artists. If they’re in discussion with us, it’s because they think we can help.

6. Be prepared to walk awaySometimes the author and the editor are simply not a good fit for each other. In the case of fiction, this can be because the editor can't emotionally connect with the story.

7. Decide whether fiction's a good fit for youThere are challenges and benefits to fiction editing and proofreading.

8. Do a short sample edit before you commitUnless you’ve previously worked with the author, work on a short sample so that you know what you’re letting yourself in for.

9. Query like a superhero!All querying requires diplomacy, but fiction needs a particularly gentle touch.

10. Keep your clients' mistakes to yourselfSome of our self-publishing clients are pulled a thousand-and-one ways every day. And, yet, they’ve found the time and energy to write a book. We must salute them. Some are right at the beginning of the journey. There’s still a lot to learn and they’re on a budget; they’ve not taken their book through all the levels of professional editing that they might have liked to if things had been different. Some haven't attended writer workshops and taken courses, and they probably never will – there’s barely enough time in the day to deal with living a normal life, never mind writing classes. They’re doing the best they can. With that in mind, respect the journey.

We must always, always respect the writer and their writing, and acknowledge the privilege of having been selected to edit for them. Those are my 10 tips for working with indie fiction writers! I hope you find them useful as you begin your own fiction-editing journey!

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

This post shows you how you can use commas and conjunctions to alter the rhythm of a sentence. Changing the rhythm can help your readers immerse themselves deeper in the mood of your narrative and the emotions of your characters.

Standard grammar advice – the stuff we learned when we were kids – calls for lists with three or more items (or phrases or clauses) in a sentence to be separated by a comma, and for a conjunction to be inserted before the final item:

Her arsenal of weapons included rifles, pistols and machetes. Or, if your preference is to use the serial (or Oxford comma): Her arsenal of weapons included rifles, pistols, and machetes. The use of this one conjunction is called syndeton, and it moderates the pace. When it comes to fiction, standard grammar works very well for the most part. However, there are other accepted literary devices you can use to help your readers feel the scene you’ve written in a different way: asyndeton and polysyndeton. I’ve used examples from crime fiction in this article but the principles apply across genres. More on syndetic constructions Syndeton is everywhere. It’s the most oft-used way of constructing a sentence with multiple clauses, and it works well because it aids clarity: this thing, that thing and that other thing. Here’s an excerpt from At Risk by Stella Rimington (p. 369): And here’s an example from Jo Nesbo’s first Harry Hole thriller, The Bat (p. 250): This second excerpt is taken from a chapter in which the head of the crime squad, Neil McCormack, delivers a long speech to the protagonist, Harry Hole. Harry has just spent nearly an hour delivering his own monologue, updating McCormack on everything that’s happened so far. The mood of the entire scene is one of contemplation and resignation. The characters give each other the space to talk without rushing. Their behaviour feels controlled, and the way they talk is measured. The grammatical structure of the sentence (syndetic) is a good choice because it moderates the speed at which we read, and reflects the mood. Omitting conjunctions – asyndeton Authors might choose on occasion to change the mood of a sentence by deliberately removing the conjunction. Separating all the items with only commas accelerates the rhythm. That speeding-up can have a variety of effects:

Let’s go back to the Nesbo example and see what happens when we change it: ‘They helped the Allies against the Germans and the Italians, the South Koreans against the North Koreans, the Americans against the Japanese and the North Vietnamese.’ By omitting the conjunction and inserting a comma, a sense of frustration and urgency is introduced. It’s subtle, certainly, but that’s the beauty of it. If Nesbo had wanted to convey more immediacy, he could have elected to make these small changes. They would have altered the rhythm and showed (without spelling it out) that McCormack’s tone had changed or the pace of his speech had increased. Here are two examples from Robert Ludlum’s The Janson Directive (p. 274 and p. 355): In the example above, Ludlum could have introduced ‘and’ after/instead of the final comma of the first sentence with no detrimental effects, but I think its omission brings a sense of urgency and determination to the writing that reflects the tension of the scene. In the excerpt below, he uses asyndeton to evoke a sense of futility, frustration and anger. The reader is forced to become bogged down in the senseless loss of life from a bullet to the head:

‘Another dumb, inanimate slug would shatter another skull, and another life would be stricken, erased, turned into the putrid animal matter from which it had been constituted.’

Asyndetic constructions can be particularly effective in noir and hardboiled crime fiction. These genres don’t shy away from the dark underbelly of their settings. The characters are often as damaged as the gritty environments they work within, and a sense of hollowness and futility underpins the novels. Here’s an excerpt from The Little Sister (p. 177) by the king of hardboiled, Raymond Chandler: Imagine that second sentence with ‘and’ after (or instead of) the final comma. It would ruin the flow and remove the utter sense of despair and hopelessness. Chandler doesn’t overdo it though. He saves his use of the asyndetic for the right moments rather than littering his pages with it. Using multiple conjunctions – polysyndeton Another technique for altering rhythm is that of using multiple conjunctions. Polysyndetic constructions are interesting in that they can work both ways:

In the following example, Chandler (p. 103) shows us two different groups of people waiting in a reception area that the main character, Philip Marlowe, has entered. By using a conjunction between each adjective describing the hopefuls, he enhances the brightness of their mood. This in turn tells us more than Chandler gives us in terms of words about the other group. We can imagine their boredom and frustration:

‘There was a flowered carpet, and a lot of people waiting to see Mr Sheridan Ballou. Some of them were bright and cheerful and full of hope. Some looked as if they had been there for days.’

There’s a powerful example of the polysyndetic in Kate Hamer’s The Girl in the Red Coat (p. 151). Hamer uses it to enrich a child-character’s voice. Carmel has been abducted and is experiencing a kind of dislocation as she plays with two other children. The multiple conjunctions serve to emphasize the overwhelming giddiness. There’s almost no time to take a breath: Beware the comma splice Asyndeton should not be confused with the comma splice. A comma splice describes two independent clauses joined by a comma rather than a conjunction or an alternative punctuation mark. I recommend you avoid it because some readers will think it's an error and might leave negative reviews. The standard-punctuation column in the table below shows how the authors have got it just right. The right-hand column shows you how the non-standard comma-spliced versions would appear.

I hope this overview of syndeton, asyndeton, polysyndeton and the comma splice will help you to discover new ways of playing with the rhythm of your own writing while keeping the punctuation pedants at bay!

Resources and works cited

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with independent authors of commercial fiction, particularly crime, thriller and mystery writers. She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Society for Editors and Proofreaders (SfEP), a member of ACES, and a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi).

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. |

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed