|

In this episode of The Editing Podcast, Louise Harnby and Denise Cowle talk to thriller writer Andy Maslen about the creative-writing process.

Listen to find out more about

Here's where you can find out more about Andy Maslen's thrillers. Dig into these related resources

Music Credit ‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

0 Comments

This post explains when and how to indent your narrative and dialogue according to publishing-industry convention.

The purpose of first-line indents

Each new paragraph signifies a change or shift of some sort ... perhaps a new idea, piece of action, thought or speaker, even a moderation or acceleration of pace. Still, the prose in all those paragraphs within a section is connected. Paragraph indents have two purposes in fiction:

First lines in chapters and new sections Chapters and sections are bigger shifts: perhaps the viewpoint character changes, or there's a shift in timeline or location. To mark this bigger shift in a novel, it’s conventional not to indent the first line of text in a new chapter or a new section. You might hear editorial folks refer to this non-indented text as full out.

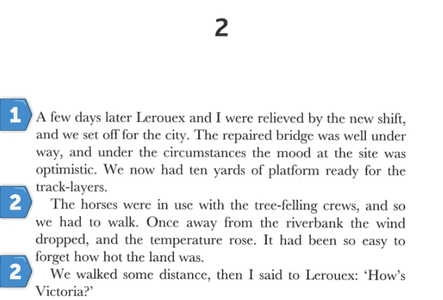

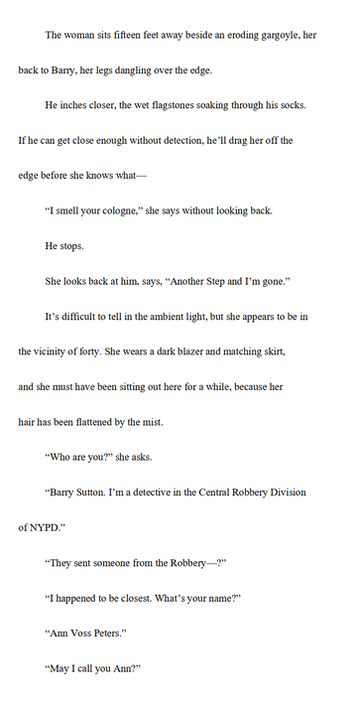

NARRATIVE LAYOUT The following example is taken from Part 5, Chapter 2, of Christopher Priest’s Inverted World (p. 287, 2010):

And here's an example from Part 2, Chapter 6, p. 147, which shows how the layout works the same after a section break:

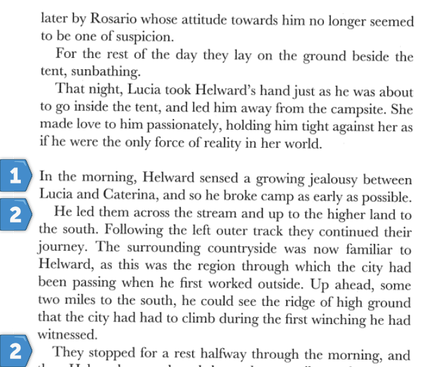

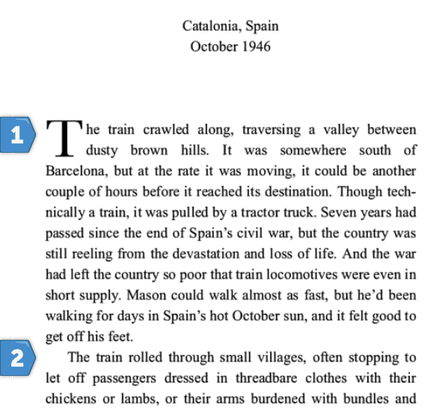

Even if an author chooses to include a design feature such as a dropped capital (sometimes called a drop cap), it's standard for that letter to be full out, as shown in the following example from To Kill a Devil (John A. Connell, p. 6, Nailhead Publishing, 2020):

DIALOGUE LAYOUT

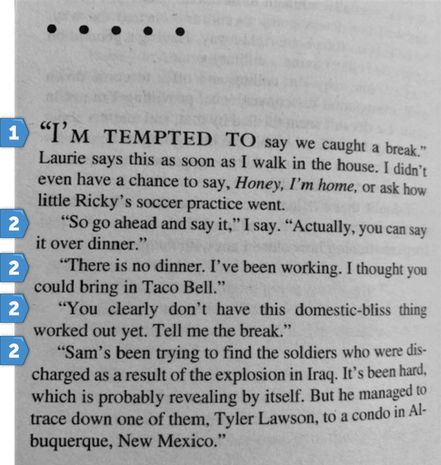

The same applies even if the chapter or section starts with dialogue, as in this excerpt from David Rosenfelt's Dog Tags (p. 192, Grand Central, 2010):

Body text: dialogue and narrative

The example below from Blake Crouch's Recursion (p. 4, Macmillan, 2019) shows how the indentation works in the body text when there's a mixture of dialogue and narrative.

IMPACT OF LINE SPACING

Even if you've elected to set your book file with double line spacing (perhaps at the request of a publisher, agent or editor), the indentation convention applies. Here's the Recursion example again, tweaked to show what it would look like:

Indenting text that follows special elements

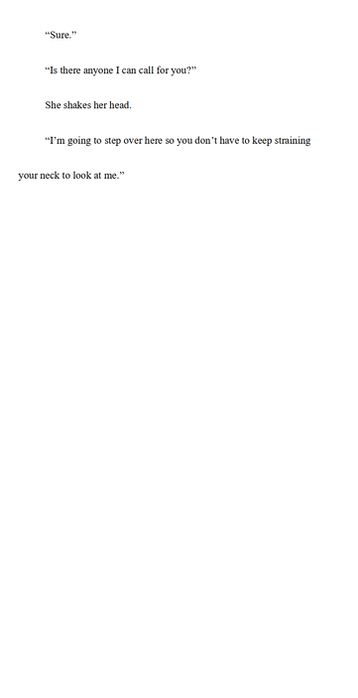

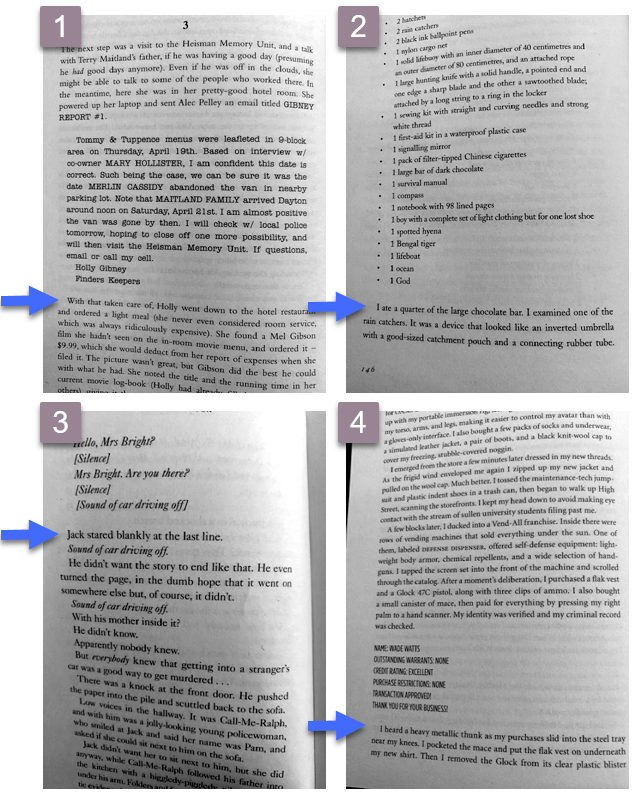

Your novel might include special elements such as letters, texts, reports, lists or newspaper articles. Authors can choose to set off these elements with wider line spacing, but how do we handle the text that comes after? Again, it's conventional to indent text that follows this content, regardless of whether it's narrative or dialogue. That's because of the connective function; the text is part of the same scene. Here are some examples from commercial fiction pulled from my bookshelves.

It's not the case that full-out text is never used, or can't be used, but fiction readers are used to conventions. When a paragraph isn't indented, they assume it's a new section, which creates a tiny disconnect.

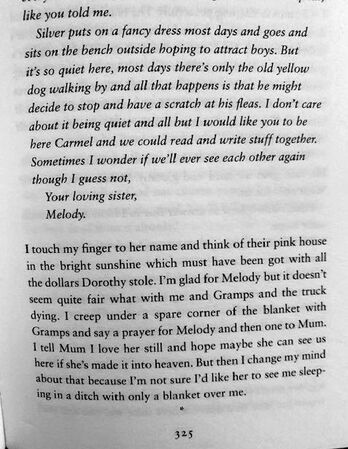

That's what I think's happened in the example below from Kate Hamer's The Girl in the Red Coat (p. 325, Faber & Faber, 2015). Of course, it took me only a split second to work out that the narrator is referring to the preceding letter, but it's a split second that took me away from the story because I'd assumed I was looking at a section break. My preference would be to indent 'I touch my finger [...]' because that text is part of the scene, not a new section.

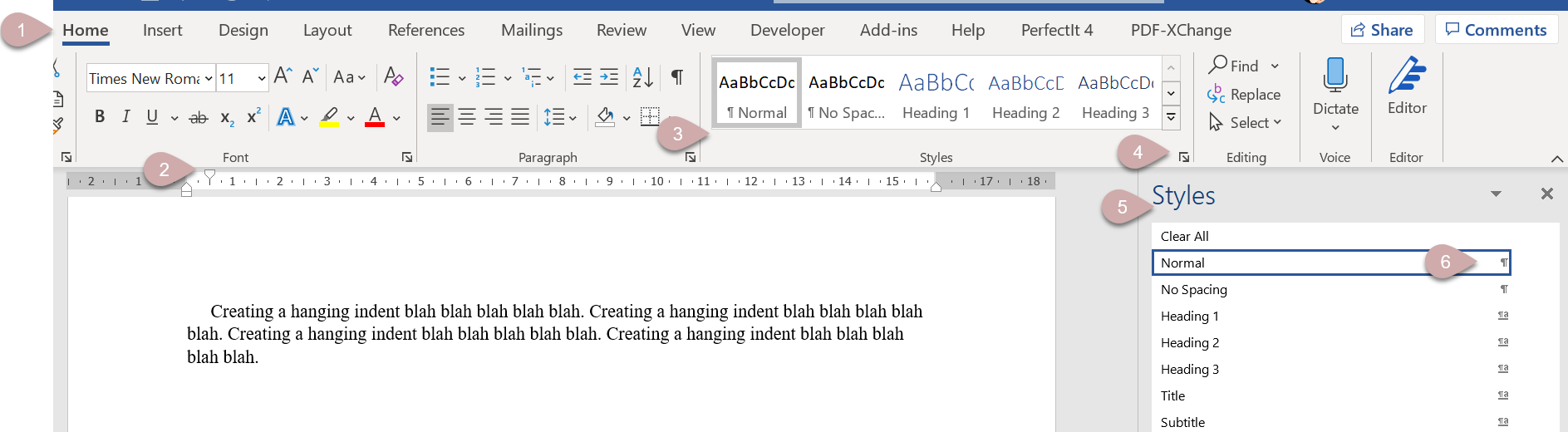

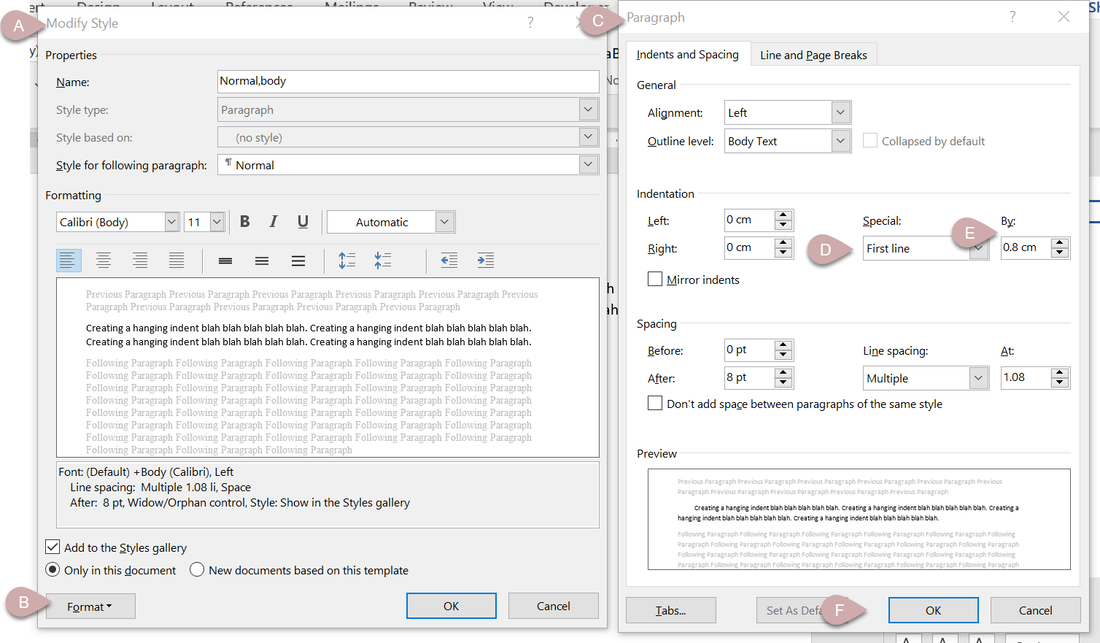

How to create a first-line indent in Word

Let's finish with some quick guidance on creating first-line indents. Avoid using spaces and tabs to create indents in Word. Instead, create proper indents. There are several ways to do this.

OR

Create a new style for your full-out paragraphs using the same tools.

If you need more assistance with creating styles, watch this free webinar. There's no sign-up; just click on the button and dig in.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

In this episode of The Editing Podcast, Louise and Denise talk to Barry Award-nominated thriller writer John A. Connell about moving from Berkley (Penguin USA) to independent publishing.

Click to listen to Season 4, Episode 12

Listen to find out more about:

Top tips From John

Contact John A. Connell Subscribe to John's newsletter and get a free book:

Editing bites

Ask us a question The easiest way to ping us a question is via Facebook Messenger: Visit the podcast's Facebook page and click on the SEND MESSAGE button. Music credit ‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

In this episode of The Editing Podcast, Louise and Denise chat with Brunella Costagliola, a specialist military writer and editor, about what makes a compelling military story.

Click to listen to Season 4, Episode 11

Listen to find out more about:

Contact Brunella

Editing bites

Music credit ‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

In this episode of The Editing Podcast, Louise and Denise talk to fellow editor Maya Berger about working on erotica and adult fiction.

Click to listen to Season 4, Episode 10

Listen to find out more about:

Contact Maya

Editing bites Ask us a question The easiest way to ping us a question is via Facebook Messenger: Visit the podcast's Facebook page and click on the SEND MESSAGE button. Music credit ‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

In this episode of The Editing Podcast, Denise and Louise discuss the growth of audio in the book world, and how using sound creates reader engagement and helps build a fan base.

Click to listen to Season 4, Episode 9

Listen to find out more about:

Editing bites and other resources

Music credit ‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

In this episode of The Editing Podcast, Louise and Denise discuss whether working with a specialist editor is necessary for all books and every type of editing.

Click to listen to Season 4, Episode 8

Listen to find out more about:

Editing bites and other resources

Music credit ‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

In this episode of The Editing Podcast, Louise and Denise chat about 18 blogs for authors and editors that offer guidance on various aspects of writing craft.

Click to listen to Season 4, Episode 7

Listen to find out more about:

Editing bites and other resources

Music credit ‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

In this episode of The Editing Podcast, Denise and Louise chat with book coach and editor Lisa Poisso about honing story craft before embarking on expensive structural and line editing.

Click to listen to Season 4, Episode 4

Listen to find out more about:

Contacting Lisa Poisso

Editing bites and other resources

Music credit ‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

In this episode of The Editing Podcast, Louise and Denise talk to technical writer and editor John Espirian about content marketing, editing and bringing a book to market.

Click to listen to Season 4, Episode 3

Listen to find out more about:

Contacting John Espirian Editing bites and other resources

Music credit ‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with independent authors of commercial fiction, particularly crime, thriller and mystery writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Are you storytelling-telling? Too much told narrative can force the reader to experience a story through extraneous layers that add clutter rather than clarity. Here’s how to identify one type of told prose and write with more immediacy.

|

|

You stand up, reach forward and take the neatly folded handkerchief out of the breast pocket of his jacket, flick it open and wipe the blade of the Marttiini on it until the knife is clean. The knife comes from Finland; that’s why the name has such a strange spelling. It hasn’t occurred to you before, but its nationality seems appropriate now and even funny in a grim sort of way; it’s Finnish and you’ve used it to finish Mr Persimmon.

|

And in this example from a later chapter (p. 90), we’re back with the protagonist. Here, the main narrative tense is present. The viewpoint is first-person:

RECOMMENDATION

The present tense is great if you want to shorten the distance between the reader and the viewpoint character.

Present tense works particularly well for short fiction because space is limited. I use it often in my own shorts and flashes because it enables me to pack an immersive punch quickly.

However, it’s tricky to manage if there are multiple viewpoint-character chapters or sections, all operating in the present tense. You’ll need to keep a close eye on the timelines so that the reader’s clear on what ‘now’ really means. If your plot twist hinges on deliberately duping them via your use of tense rather than story craft, you’ll break their trust.

The present tense can also be tiring for readers because it’s emotionally immersive. If you’re writing a novel, you might consider using it only for certain viewpoint characters – your transgressor or victim, for example.

In Let Me Lie, Clare Mackintosh mixes it up: the Anna-viewpoint chapters are set in first-person present; the Murray-viewpoint chapters are third-person past.

The past tense

Now let’s turn to the past tense, starting with some basic examples:

- Simple past: I wrote a novel; he wrote a novel

- Past progressive: I was writing a novel; he was writing a novel

- Past perfect: I had written a novel; he had written a novel

- Past perfect progressive: I had been writing a novel; he had been writing a novel

- Habitual past: I would write a chapter every week; he would write a chapter every week; I used to write a chapter every week; he used to write a chapter every week

The past tense is the choice of most contemporary commercial fiction writers. What’s interesting is that readers are so used to this style that they can still immerse themselves in a past-tense narrative as though the story is unfolding now.

Here’s an excerpt from T. M. Logan’s 29 Seconds (p. 73). We’re given a past-tense narrative with a third-person limited viewpoint (Sarah’s):

WHEN PAST TENSE FLOPS – UNDERSTANDING PAST PERFECT

Less experienced writers can end up in a pickle when referencing events that happened earlier than their novel’s now.

The crucial thing to remember is that when we set a novel in the past tense, anything that happens in the story’s past will likely need the past perfect, at least when the action is introduced.

|

What you want the reader to experience

|

What tense you should write in

|

|

Now – the present of your novel

|

Simple past or past progressive

(she stood; she was standing) |

|

Something that happened before now (i.e. in the novel’s past)

|

Past perfect

(she had stood; she had been standing) |

|

She stood there for a moment, taking in the white Christmas lights Samantha had wound through the slats of her bed’s headboard, and the fuzzy green-and-blue rug the two of them had found rolled up by the curb of a posh apartment building on Fifth Avenue. “Is someone actually throwing this out?” Samantha had asked.

|

When we’re told that ‘She stood’, that’s the novel’s now. But when the narrator recalls events that happened further back in time (bold) – Samantha’s decorating her bed, and the two women’s procuring a rug – these need to be anchored in the past-perfect tense: had, had been.

When authors fail to anchor past events in a novel whose now is already set in the past tense, the reader will be confused.

RENDERING BYGONE ROUTINE – UNDERSTANDING HABITUAL PAST

Now and then, you might want to reference events from your novel’s past that happened routinely or habitually. This is where the habitual past tense comes into play, and the tools are would and used to.

This excerpt from The Templar's Garden by Catherine Clover illustrates the usage. The narrative is set in third-person past but the viewpoint character is recalling regular journeys taken earlier in her life:

And in Time To Win (p. 62), Harry Brett uses the simple past and past progressive for the most part, but then Frank, the viewpoint character, recalls something he’d done habitually in former times:

|

Tatty was talking to Simon. Frank couldn’t hear what they were saying. He looked down the road, towards the harbour and the dead end, the industrial buildings laid low by the unexpected weight of late summer sun, and somewhere over to his left the top of Nelson’s Monument, clear of cloud for once. He used to enjoy driving down South Denes Road and curving back round onto South Beach Parade, accelerating past the old Pleasure Beach and into a different era.

|

Like the past perfect, the habitual past acts as an anchor, so that readers don’t mix up the reminiscence of a routine event with the novel’s now.

To see that confusion in action, replace ‘used to enjoy’ with the simple past: ‘enjoyed’. It reads as if Frank is enjoying driving down South Denes Road right now.

If you don’t want to use the habitual past, then an alternative anchor is necessary. Here I’ve added an anchoring clause and changed the tense to past perfect (he’d, or he had):

- Back in the day, he’d enjoyed driving down [...]

RECOMMENDATION

The past tense is flexible; it’s easier to shift narrative distance (the distance between the reader and the narrator) than is the case with the present tense, though this does increase the risk of flatter writing. Dramatic scenes – fights, escapes, arguments – could end up laboured if the writing isn’t lean and rich.

Still, it’s traditional and readers are used to it. No one will get tired of reading in the past as long as the line craft is strong.

Do take care, however, with rendering events that have taken place in your novel’s past. Use the past perfect or the habitual past when necessary to ensure your readers know what happened when.

Summing up

Write in the tense you feel most comfortable with, and that you think readers of your genre will be most comfortable reading. The past and the present both have their challenges and their advantages. The most important thing is that readers know where and when they are in the story.

Cited sources

- 29 Seconds, T. M. Logan, Zaffre, 2018

- Complicity, Iain Banks, Abacus, 1994

- The Templar’s Garden, Catherine Clover, The Holywell Press, 2017

- The Wife Between Us, Greer Hendricks and Sarah Pekkanen, Pan, 2018

- Time to Win, Harry Brett, Corsair, 2017

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

The Editing Podcast, S2E8: Publishing with an independent press: In conversation with Salt

19/8/2019

Listen to find out more about:

- The Salt story: awards, authors and publishing goals

- Author retention

- Indie publishing and the digital revolution

- The submission process

- The author–publisher relationship

- The publishing process

- Rights, sales and royalties

- Print runs

- Resources for authors

Find out more

- Visit the Salt website

Editing bites

- Typographic Style Handbook: A Guide to Typography by Michael Mitchell and Susan Wightman

- Understanding Show, Don’t Tell by Janice Hardy

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Listen to find out more about:

- Why authors change editors

- Planning ahead and giving notice

- Whether the editor should get involved in sourcing a replacement

- Checking T&Cs and cancellation policies

- Information and tools to share with the new editor

Editing bites

- The NCW Podcast (National Centre for Writing)

- Oxford Dictionary of English Idiom

- Cambridge Dictionary of American Idioms

Other resources

- The Editing Podcast, S1E1: The different levels of editing

- The Editing Podcast, S1E10: How to find an editor

- The Editing Podcast, S1E7: Style sheets for writing and editing

- Blog article: How do I find a proofreader, copyeditor or developmental editor?

- Blog article: What's a style sheet and how do I create one? (includes a free downloadable style-sheet template)

- The different levels of editing (free webinar)

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Listen to find out more about:

- What PerfectIt does

- Who uses PerfectIt

- What’s new with PerfectIt 4

- Using the onboard styles

- The PerfectIt 4 interface

- How to access PerfectIt on PC and Mac

- How much a subscription costs and what’s included

- Where to download PerfectIt

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Listen to find out more about:

- The confident writer

- The nervous writer

- The reluctant writer

- The impatient writer

Editing bites

- ‘How to proofread your own writing – 10 tips to clean up your writing’

- ‘Is proofreading enough? Does Your Reader Dance?’

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Listen to find out more about:

|

|

Editing bites

- Editing in Word, 2nd Edition, by Adrienne Montgomerie

- How to Market a Book, by Joanna Penn

Other resources

- Review of Montgomerie’s Editing in Word, 2nd ed. by Louise Harnby (blog post)

- How to use styles (free tutorial)

- How to use styles (blog post)

- PerfectIt

- Formatting in Word: Find and Replace (booklet containing raw-text tidy-up tips)

- Proofreading checklist (free PDF booklet, available when you sign up to The Editorial Letter)

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Good dialogue is the icing on the cake of a well-structured novel. Bad dialogue will mar a well-structured narrative and bury a story that is barely hanging in there. Before we look at what makes great dialogue, let’s look at what dialogue isn’t:

- It’s not everyday conversation – much of that is boring and has no place in a novel.

- It’s not a narrative – that tells us what’s happening in a story. Dialogue should show us how characters respond to those events.

- It’s not a tool to set up the next character’s lines – that’s a waste of words on the page. Every line should have a purpose, whoever’s speaking it. Every line should tell us something about the character – who they are, how they’re feeling and what they want.

- It’s not a backstory-delivery mechanism that the characters are already familiar with – that’s maid-and-butler dialogue and a misfire.

- It’s not a monologue – that’s best left for viewpoint characters mulling things over in their own time, unless your intention is to show one person being bored rigid by another. If only one person’s doing all the talking, ask yourself why the other person on the page is still in the room.

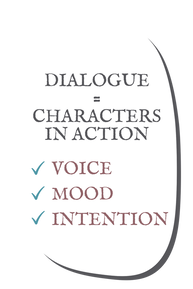

3 components of effective dialogue

‘Dialogue should be the character in action,’ says John Yorke in his must-read Into the Woods (p. 151). Yorke’s talking about the art of screenwriting but the advice is just as pertinent for novelists. I recommend you read it even if you have no intention of writing for the screen because it’s a masterclass in storytelling, whatever the medium.

When we stop thinking about dialogue as words spoken – as conversations – and instead frame it in terms of characters, we create something that’s fit for a novel.

What does your dialogue tell readers about who your characters are, how they’re feeling, and what their motivations are?

|

3 COMPONENTS OF EFFECTIVE DIALOGUE

|

- Character intent: How characters speak tells us what they want to do. Perhaps they’re asking questions for the purpose of discovery and understanding whodunit (doctors, lawyers, PIs and police officers regularly use dialogue in novels to this end), but dialogue can express a multitude of motivations. Ask yourself what your character wants every time they open their mouth.

Unreliable dialogue

What a character expresses through dialogue need not match their true voice, mood or intent. Unreliable dialogue is powerful precisely because it jars the reader by masking the truth (which the characters themselves may even have buried).

Imagine this scenario: John has been kidnapped by Jane. They met in a club where she spiked his drink. He started to feel unwell and she offered him a ride to the Tube station. He never made it. He’s been held captive for several days, during which time he’s been physically abused and deprived of food. He’s frightened out of his wits, and weak to boot.

The dialogue between John and Jane could go as follows: John raves and rants, telling Jane her behaviour is monstrous, that Jane’s going to pay for her actions and that he’s going straight to the police as soon as he’s escaped. Jane responds in fury, telling John he deserves it all and how there’s no way he’ll ever escape.

Or the dialogue could be unreliable. John might be polite, sycophantic even, as he thanks her for the water she provided, compliments her on her appearance, or asks her about her life. Through that speech, we are shown his desperation. It’s about keeping her on side and calm in order to save himself.

And Jane’s verbal response might be chipper, seductive even. Through that dialogue, we are shown her psychosis.

The result is a sinister verbal exchange that allows us to explore the inner workings of the characters’ minds without it being forced down our throats via an all-to-obvious narrative that’s centred around the viewpoint character.

Breaking free of viewpoint limitations

Most novelists opt to hold third- or first-person narrative viewpoints. That means the story in a chapter plays out through one person’s perspective.

When authors drop viewpoint, readers end up playing a game of narrative table tennis in which they bounce from one character’s head to another. We know who everyone is (voice), what everyone’s feeling (mood), and what everyone wants (intention) all of the time. Readers become disengaged because they don’t have time to immerse themselves in any one character’s experience.

Good dialogue allows writers and readers to break free without head-hopping. Through dialogue, readers can intuit the voice, mood and intention of multiple characters, yet the singular narrative viewpoint remains true throughout. That keeps the reader engaged and the writing taut.

Purposeful dialogue in action

Here’s an excerpt from Lee Child’s Never Go Back (pp. 457–8). I chose it because I’ve also seen the movie, which allowed me to compare my experience of the screen dialogue (and the advice Yorke gives) with the novel’s, and because there are no action beats, only two speech tags and no narrative. It’s just dialogue between a teenage girl and Jack Reacher.

Reacher said, ‘No you’re not in trouble. We’re just checking a couple of things. What’s your mom’s name?’

‘Is she in trouble?’

‘No one’s in trouble. Not on your street, anyway. This is about the other guy.’

‘Does he know my mom? Oh my God, is it us you’re watching? You’re waiting for him to come see my mom?’

‘One step at a time,’ Reacher said. ‘What’s your mom’s name? And, yes, I know about the Colt Python.’

‘My mom’s name is Candice Dayton.’

‘In that case I would like to meet her.’

‘Why? Is she a suspect?’

‘No, this would be personal.’

‘How could it be?’

‘I’m the guy they’re looking for. They think I know your mother.’

‘You?’

‘Yes, me.’

‘You don’t know my mother.’

‘They think face to face I might recognize her, or she might recognize me.’

‘She wouldn’t. And you wouldn’t.’

‘It’s hard to say for sure, without actually trying it.’

‘Trust me.’

‘I would like to.’

‘Mister, I can tell you quite categorically you don’t know my mom and she doesn’t know you.’

‘Because you never saw me before? We’re talking a number of years here, maybe back before you were born.’

‘How well are you supposed to have known her?’

‘Well enough that we might recognize each other.’

‘Then you didn’t know her.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Why do you think I always eat in here?’

‘Because you like it?’

‘Because I get it for free. Because my mom works here. She’s right over there. She’s the blonde. You walked past her two times already and you didn’t bat an eye. And neither did she. You two never knew each other.’

WHAT WE LEARN

- Viewpoint: Reacher is the viewpoint character. However, through the dialogue, readers are able to access information about him and the teenager.

- Voice: Both characters speak in a no-nonsense fashion. Reacher might think he holds the balance of power, given his job and age, but the girl’s streetwise tone suggests she thinks otherwise; they’re equals.

- Mood: Reacher is calm (we’d expect nothing more) and measured, but there is emotional engagement; he seems keen not to give too much away (probably in respect of the fact that he’s talking to a child, perhaps his daughter). As for the girl, she’s almost disinterested. I imagine her stuffing fries into her mouth, as focused on her food as she is on the conversation ... until she thinks her mother might be in trouble. Child doesn’t tell us, but I can see her in my mind’s eye, mouth full, looking at him, just a twitch of alarm registering in her expression. There’s almost a sense of the traditional mother/daughter relationship reversed; this is a kid who’s used to looking after herself. There’s movement in this dialogue; the speech is infused with its own action beats.

- Intent: Reacher wants to find out who the mother is. This exchange is all about building trust with the girl in order to achieve that. The girl needs someone she can turn to because bad people are watching her and her mother. She wants to know how Reacher might know Candice; Reacher wants to keep the possible sexual encounter and his resulting paternity to himself. The girl’s not stupid and picks up on his vague inference to a sexual encounter. As the conversation and the chapter close, Reacher and the readers discover that Candice and our protagonist have never met, and that the girl can’t be his daughter.

This is characters in action, expressed through speech. Child makes every line count towards the chapter denouement. If he was tempted to introduce narrative and action beats that ensured we’d get it, it doesn’t show. In fact, they would have been interruptions and slowed the pace. Instead, he trusts us to do the work because the dialogue gives us everything we need.

Here’s an excerpt from The Poison Artist by Jonathan Moore (pp. 244–5). I chose this because of the contrast between Kennon and Emmeline’s speech.

This time, his voice wasn’t much more than a whisper.

[...]

“Inspector, you’ll hit somebody,” Emmeline said.

[...]

“You look sick, Inspector,” Emmeline said. “I could get you something to drink. A glass of water, maybe? Something a little stronger?”

Kennon fired again and Emmeline didn’t even flinch.

The bullet missed her by ten feet, punching a hole in the back of the building.

“Stop—”

“You should be more careful what you touch,” Emmeline said. “Some things can go right through the skin.”

WHAT WE LEARN

- Viewpoint: Even though Emmeline isn’t the viewpoint character, we get to access her transgressor headspace through the dialogue, and the result is powerful and sinister.

- Voice: Kennon doesn’t say much, but what he does say is what we’d expect from a trained inspector, though it’s offered quietly. Emmeline, however, is pathologically measured. We’re left in no doubt that she’s dangerous.

- Mood: We sense Kennon’s fear and desperation through his truncated, whispered speech. There’s almost exhaustion in play. Emmeline, in contrast, is seductive (offering him a drink as if she were hosting a dinner party). Given the torture in evidence, her dialogue is obscene.

- Intent: Kennon is trying to save himself, Caleb and the twitching man, but he’s playing by the rule of law, warning Emmeline that he will fire his gun. Emmeline wants to finish her game, and her desire to play is evident in her speech. Of course, this may be unreliable; it could be masking a deep-seated fear that she’ll be harmed or killed.

This, too, is characters in action, expressed through speech. Moore draws us deep into the transgressor’s mind – even though she’s not the viewpoint character. Her dialogue, juxtaposed with Kennon’s exhausted near-silence, generates a powerful scene that oozes with sickly tension.

Here’s a third example from Harlan Coben’s Run Away (pp. 68–9):

Ingrid wore a long thin coat. She dug her hands into her pockets. “Go on.”

“Aaron was mutilated.”

“How?”

“Do you really need the details?” he asked.

[...]

“According to Hester’s source, the killer slit Aaron’s throat, though she said that’s a tame way of putting it. The knife went deep into his neck. Almost took off his head. They sliced off three fingers. They also cut off ...”

“Pre- or post-mortem?” Ingrid asked in her physician tone.

“The amputations. Was he still alive for them?”

“I don’t know,” Simon said. “Does it matter?”

WHAT WE LEARN

- Viewpoint: Simon is the viewpoint character but through Ingrid’s speech we learn how she uses her professional mindset to manage stressful situations.

- Voice: Simon’s voice is emotional and verbose; Ingrid’s is precise and clinical.

- Mood: Simon’s disgust and distress are evident. You can almost feel the words falling out of his mouth. Ingrid’s speech exudes clinical detachment. She’s in doctor mode.

- Intent: Simon wants to unload. Ingrid wants to understand.

Again, through speech we see the characters in action. The contrasting voices and moods show us Simon and Ingrid’s different intentions. There’s no need for more than a peppering of supporting narrative.

Summing up

- Make your characters’ speech count. Use it to show who the character is (voice), how they feel (mood) and what they want (intention).

- Play with unreliable dialogue if it will enhance our understanding of characters’ emotions and motivations. Those deliberate juxtapositions will deepen our engagement.

- Realistic everyday speech, while authentic, is dull, invasive and will disengage your reader. Remove it!

Free dialogue enrichment tool

To help you think about your characters' voices, moods and intentions, and how these will enrich your dialogue, download this tool. It's a fillable PDF with ready-made examples and space for you to record your own decisions.

|

Cited sources

|

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

BLOG ALERTS

TESTIMONIALS

Dare Rogers

'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'

Jeff Carson

'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'

J B Turner

'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'

Ayshe Gemedzhy

'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'

Salt Publishing

'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'

CATEGORIES

All

Around The World

Audio Books

Author Chat

Author Interviews

Author Platform

Author Resources

Blogging

Book Marketing

Books

Branding

Business Tips

Choosing An Editor

Client Talk

Conscious Language

Core Editorial Skills

Crime Writing

Design And Layout

Dialogue

Editing

Editorial Tips

Editorial Tools

Editors On The Blog

Erotica

Fiction

Fiction Editing

Freelancing

Free Stuff

Getting Noticed

Getting Work

Grammar Links

Guest Writers

Indexing

Indie Authors

Lean Writing

Line Craft

Link Of The Week

Macro Chat

Marketing Tips

Money Talk

Mood And Rhythm

More Macros And Add Ins

Networking

Online Courses

PDF Markup

Podcasting

POV

Proofreading

Proofreading Marks

Publishing

Punctuation

Q&A With Louise

Resources

Roundups

Self Editing

Self Publishing Authors

Sentence Editing

Showing And Telling

Software

Stamps

Starting Out

Story Craft

The Editing Podcast

Training

Types Of Editing

Using Word

Website Tips

Work Choices

Working Onscreen

Working Smart

Writer Resources

Writing

Writing Tips

Writing Tools

ARCHIVES

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

October 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

October 2016

September 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

March 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

November 2015

October 2015

September 2015

July 2015

June 2015

May 2015

March 2015

February 2015

January 2015

November 2014

October 2014

September 2014

August 2014

July 2014

June 2014

March 2014

January 2014

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

August 2013

June 2013

February 2013

January 2013

November 2012

October 2012

September 2012

August 2012

July 2012

June 2012

May 2012

April 2012

March 2012

February 2012

January 2012

December 2011

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed