|

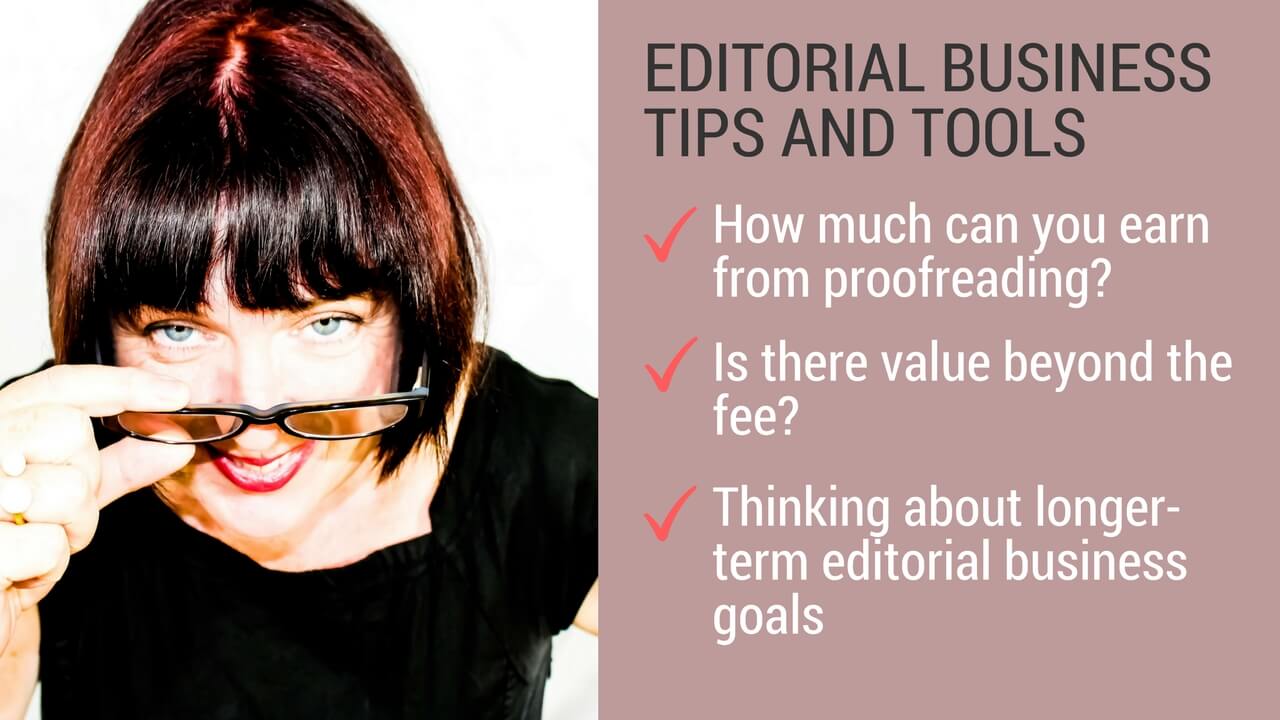

Freelance proofreading won’t make you rich, but you can earn a reasonable wage from the job if you can build up a bank of regular, trustworthy clients.

With few set-up costs, no travelling expenses, and pretty much all the flexibility you want, it can be an exciting and fulfilling way of earning a crust. The question I get asked most often by those looking to break into our industry is "How much can you earn?"

There’s no straightforward answer to this – the following provide some food for thought.

Recommended or suggested rates In the UK, the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) suggests a minimum hourly rate of £25.40 for proofreading (correct in 2019). The rate for copyediting is higher and depends on what level of intervention is required. Whether you can earn this will depend on who you work for and what skills you have. Some publisher clients are moving away from hourly rates, and towards fixed rates per job. Your efficiency and ability to work comfortably in different formats and using ancillary software (onscreen – Word or Acrobat, for example) will therefore determine your hourly rate. You’ll probably improve your efficiency as you become more experienced, too. And if you work for a client on a regular basis, you’ll become familiar with their house style, which will speed you up. Different specialty areas command different rates In the mainstream publishing sector, expect to earn higher rates if you proofread science, technical or medical materials. Clients tend to prefer people with a background in these fields, and the level of technical expertise required can mean earnings at the higher end of the rates spectrum. In the social sciences, on the other hand, the rates tend to average out lower. In my experience, social science publishers pay anything between £11 and £18 per hour. This is only a ballpark figure, however (see the point above about fixed rates per job). The trade publishing sector rarely gets anywhere near the CIEP recommended rates. The books are diverse and fun, but you’ll have to compromise on the pay! Setting your own rates If you are bidding on proofreading jobs online, working for indie authors, proofing for students, or focusing on the business market, you can set your own rates. Many proofreaders offer a per-word fee as well as hourly or flat-rate options. Bear in mind that work of this nature will not necessarily have been with an editor first, so it may require more intervention. Make sure your client is clear about what a proofreader does – you don’t want to agree to proofreading rates only to find out you’re copy-editing the work. You can offer higher rates for weekend work or a fast turnaround. Or you can offer discounts for lower-income groups such as students or people on benefits. Working for publishers and project management agencies (packagers) Publisher clients and project management agencies usually set their own proofreading rates. Should they decide to accept your services, you’ll have to decide whether to accept their rates. They vary enormously. If you’re a member of the CIEP you can access their annual Rate for the Job survey. One thing to remember is that book publishing is an expensive business, and those publisher clients that don’t have other revenue streams (subscription-based products like journals, for example) have very tight margins. Keeping editorial costs in line is crucial to profitability – meaning you may be disappointed with some of the rates being offered. There’s little point in grouching about it – you’re self-employed now. No one’s forcing you to take the rate so think about what your goals are – how important the client is to you, whether they can offer you repeat work, what their name will look like on your CV – and make your decision. Try negotiating by all means, but if your client won’t budge, consider this: The highest rate isn’t always the best deal in the long run – one client offering a one-off job worth £40 per hour isn’t as financially rewarding on an annual basis as another who’ll give you monthly projects at an hourly rate of £21. Repeat work means you don’t have to spend money and time on marketing yourself, so do the maths. Getting started – taking a lower rate or working for free to get experience When you’re starting out, you need experience. This is not a good time to be worrying about whether you’re getting the ‘recommended rate’. Instead, think long term – go for whatever jobs you can get to beef up your portfolio; work for free if you need to. Experience counts for a lot, as do good references. Working for little now will pay off in the future, allowing you to attract new clients and be pickier about who you want to work for and what rates you’re prepared to accept. Should you work for below-recommended rates? This is a hotly contested topic among working freelance editorial staff. Some freelance editors and proofreaders think that every time one of us accepts a ‘low’ rate we undermine the entire industry, forcing down the price. I’m not unsympathetic to this view, but I’m a pragmatist. My opinion is that it’s up to you. Once you become freelance, you’re running your own business. Don't waste time worrying about what others are charging. Their circumstances may be different to yours in so many ways. You have to decide how best to achieve your strategic goals. If accepting a rate that is considered ‘low’ enables you to acquire clients who provide you with regular work, clear briefs, and timely payment, then you may consider this an acceptable compromise. Take the long view When making your assessments, don’t just think about the rate per job – think about what you might earn from this client over the course of a year … two years … five years. In the past I've accepted work from clients who were paying below the CIEP's suggested rates, but I loved the books they published, I trusted them to put the money in my account as agreed, and they contacted me time and again. They helped make my business sustainable – because of them I’m self-employed, not self-unemployed! UPDATE: Since writing this article I've considered other aspects of the financial side of editorial freelancing that are important to consider when assessing what you can earn. To read more, see Proofreading – Does it Pay? Part II: Hidden savings and earning cultural capital.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with independent authors of commercial fiction, particularly crime, thriller and mystery writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

26 Comments

These are the books I couldn't live without and that I recommend for any proofreader's bookshelf ...

New Hart's Rules: The Handbook of Style for Writers and Editors

The Penguin Guide to Punctuation

New Oxford Dictionary for Writers and Editors

New Oxford Spelling Dictionary: The Writers' and Editors' Guide to Spelling and Word Division

Troublesome Words

Pocket Fowler's Modern English Usage (2nd Edition)

English Grammar for Dummies (UK Edition)

Business Planning for Editorial Freelancers

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

I wrote this post about proofreading training years ago. However, I'm confident the advice still stands. While these days I work primarily for indie fiction authors who find me via organic search, I think publisher work is still incredibly valuable.

How far will training get you in the editorial freelancing market?

Publishers and editorial freelancers understand each other. We have the same expectations regarding the level of editing being undertaken (e.g. developmental, line/copy, proofreading), which saves both parties time. Publishers are in a position to offer repeat work, thus taking some of the stress out of marketing. Plus the portfolio- and testimonial-building opportunities are excellent. And so while the rates are sometimes an issue (though not always by any means), publishers are a brilliant client group to target. It's therefore important to bear in mind where they see the value when hiring editorial freelancers. Here's what I found out ... Is training useless? I’ve just landed on a blog where the author calls proofreading courses a "scam" and "unnecessary", and the qualifications "useless". The rant continues, the author arguing that they’ve never been asked to produce evidence of any qualification or completion of a course by an "official" body. And luckily for anyone looking to enter this extraordinarily crowded and competitive field, said author offers a far cheaper alternative to all those "rip-off" courses: their very own proofreading course in the form of an ebook. Back in 2005, I spent seven months doing just the type of course this author was decrying. I opted for Essential Proofreading, a distance learning course run by the Publishing Training Centre (PTC), an industry-recognized body. I also joined the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), formerly the SfEP, and did the necessaries to qualify for membership. So did I waste my money? Was I ripped off? Did the training I took on help me get to where I am now or was I kidding myself? Should I have instead invested in an ebook course that would have given me change from a twenty-pound note? I discussed this issue with some of my clients, all of whom are established and respected publishing houses or project management services in the UK. What came out of the conversation led me to conclude that the training I undertook was definitely worthwhile, and membership of the CIEP/SfEP has provided me with wonderful information-sharing opportunities as well as the right to advertise in their Directory of Editorial Services. Nevertheless, there was much food for thought in the responses I received. Thumbs up for training courses … Out of House Publishing consider only the CIEP/SfEP and PTC courses to be "useful and relevant" and Managing Director Jo Bottrill stated that he "certainly consider[s] freelancers who have completed such training much more seriously". Constable & Robinson’s website states, "Please note our minimum requirements include training from recognized establishments such as SfEP or the Publishing Training Centre." Aimée Feenan from Ashgate concurs, saying that most Ashgate staff have undertaken some sort of training at the PTC, and knowing that freelance staff are able to work to the same editorial standards means they are more likely to be hired. They also recognize the CIEP/SfEP as a trusted source. And at SAGE Publishing, training is considered important, with the CIEP/SfEP and PTC again being the two most trusted external suppliers. Elizabeth Clack at Edward Elgar felt "that the Publishing Training Centre and CIEP/SfEP courses are good quality and are well-regarded, so it would be a plus point if someone had taken courses with them, although that's not to say that we would only consider freelances who had taken courses with these bodies". She added, "it indicates to us that the freelance has reached a certain level of proficiency and has some understanding of editing/proofreading procedures and 'best practice'. Training is especially relevant if the freelance does not yet have much work experience." Also of note here the fact that she felt that proofreading courses took away some of the risk of the unknown when taking on a new or inexperienced freelancer. But training in itself is not enough … Training in itself is not always enough, and some publishers feel they have had their fingers burned by relying too much on freelancers’ training credits. Increasingly publishers are using their own tests in order to evaluate competence. Jo Bottrill was cautious of advanced membership and accreditation status within the CIEP/SfEP, feeling that these did not always ensure that a freelancer met his exacting standards. Instead, he's "put[ting] more emphasis on the assessment of our own tests and analysis of live jobs. Our quality control and reporting procedures have developed over the last couple of years to ensure we have an appropriate safety net." For Edward Elgar, "another factor when considering whether to work with a freelance is whether they have experience in a particular subject area, because many of our books are quite specialized. For instance, freelances working on our law books may have law qualifications or a background in legal work." Ian Antcliff, one of SAGE Publications’ senior production editors, stated that training, though important, is seen as an add-on. For him, in-house experience makes for an attractive prospect, not because the editors/proofreaders are better, but rather because "it usually ensures that they are sympathetic to and understand the pressure that in-house staff are under (especially with regard to budgets and deadlines)". Ashgate acknowledge that not every freelancer on their books has received formal editorial training – they do have people who were just exceptionally good at learning on the job and being an expert in a particular subject area is also a real plus. Polity’s production manager, Neil de Cort, takes a stronger line. For him, a speculative letter with a list of training courses is of no relevance. Like most publishers, Polity receive a large number of speculative letters every year from freelancers looking for work. Experience counts every time – Neil wants to see that a freelancer has experience of working in the social sciences, and references from other publishers are key. Completion of a training course alone simply won’t get you on their books. Confidence to take on the task The training I’ve completed to date did indeed get me looked at by several clients when I was starting out. Polity, though, gave me work because of my knowledge of their field of publishing and a good reference from Salt Publishing. Constable & Robinson noticed me, despite the fact that I already met their minimum requirements, because of a recommendation from the Edward Elgar production team. However, proofreading books published by the likes of Cambridge University Press, Polity and SAGE, who, like all of my clients, have precise and exacting publishing standards, can be daunting to the newbie. And expanding into new publishing genres, in my case from the social sciences to trade, is a different type of challenge. Externally assessed training under the wing of a skilled industry-recognized body gave me the confidence to take on these challenges and feel assured that I was ready for the task in hand. On-the-job CPD and upgrading skills As for the future, I’ve been wrestling with the issue of whether to upgrade my CIEP/SfEP membership status. For me this will mean undertaking more training courses, since I qualify on all other fronts. [Update 2020: I've now been an Advanced Professional Member of many years.] I’ve no doubt that further courses will provide me with new knowledge and provide excellent networking opportunities. But will I get more work? It depends on what that training is – if it involves ensuring I can mark-up onscreen, use the preferred software packages, and deliver my projects in new formats, then yes. Ian Antcliff at SAGE emphasizes how essential it is for freelancers to have up-to-date skill sets "with regard to both onscreen editing and Word, and also with ancillary software generally – Adobe, etc. – increasingly so as we move towards onscreen mark-up of proof PDFs". Talking to clients (or reading their blogs and tweets) about what their needs are, how the market is changing, and new ways of delivering our service may be just as informative as any course, and is probably the first thing we should do before deciding where to spend our hard-earned training cash. In a nutshell … So all in all, the message from my clients was that initial basic editorial training is more likely to get us noticed by publishers, but that it’s not the sole factor in determining whether they place us on their books. Experience counts for a lot, but so does flexibility over the formats in which we work. Continuing to update our skills in whatever way best suits the needs of our clients will give us the best chance of remaining their freelancers of choice. As for that £19.99 ebook course? It simply wouldn’t have cut the mustard. (With thanks to Edward Elgar, SAGE Publications, Ashgate, Polity, and Out of House Publishing for their generous contributions.)

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

|

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed