|

Can you proofread and copyedit professionally without being mouse-dependent? And what if you don't have a degree? Does it matter? A reader asked me. Here's my take.

Andrew says:

I am considering taking introductory courses in proofreading and copyediting; firstly, please could I ask you about the software used. Usually I prefer to use the keyboard to move around the menus, because I find repeatedly using a mouse tiring on my hands and arms. Does (at least some of) the software used in your industry allow keyboard use as an alternative to mouse work? Secondly, would my lack of a degree hold me back? I have many years' experience in IT system development and programming; would this experience be attractive to publishers? However, I was hoping to not just to work on IT-related material! Thanks for your question, Andrew. Let’s deal with the software issue first. Software Text editing When editing raw text, most editors use Microsoft Word. There are several excellent complementary add-on programs. These increase the editor’s productivity because they allow us to do complex tasks more quickly. One example is PerfectIt, an outstanding consistency checker that can be customized to find and fix problems including hyphenation, capitalization, spelling variance, number style, italics, super/subscript, bullet punctuation, and wildcard searches. In addition, there are hundreds of free macros available to editors, all of which are designed to complement the editor’s eye. Examples include spell-checkers, proper-noun analysis tools, homonym and homophone identifiers, Then there are onboard tools in Word such as wildcard search and find/replace to name but two. And let’s not forget Word’s ribbon, which provides quick access to a range of tools, including the Styles palette. To work efficiently, you’ll need to access these tools. As long as you know (or can learn) how to access the relevant menus via your keyboard, and assign keyboard shortcuts, I see no reason why you should be dependent on a mouse. Page-proof annotation If you’re hired to proofread designed page proofs, you’ll likely be working on PDF in Acrobat Pro, PDF-XChange, Adobe Reader or similar. You’ll need to be able to use the onboard comment-and-markup tools and possibly the stamps palette. Again, providing you can learn the keyboard shortcuts, you can minimize your mouse usage. There’s a helpful list of Acrobat shortcuts on the Adobe website: A note of caution: my concern is the impact on your speed. One of the keys to being a successful independent editor is efficiency. If you’re already a seasoned mouse-independent Word and Acrobat user, and are introducing new keyboard shortcuts into your existing knowledge base, I suspect the transition will be comfortable and the impact on your speed minimal. If you’re not familiar with these programs, the tools within them, and the access keys, you’ll need practice to build your speed. In general, though, given your extensive experience in systems development and programming, I can’t see these issues being obstacles for you, Andrew. You’ve probably forgotten more about how to navigate a computer screen than I’ve ever known! Is a degree necessary? If you want to copyedit for specialist scientific editing agencies, you’ll likely need at least a Master’s in a related discipline, even a doctorate. If you plan to work for publishers or packagers (project-management agencies) with book lists in the social sciences, arts, humanities and technology, they’ll be more interested in your professional editorial training, and your ability to perform successfully in an editorial assessment. If you wish to copyedit and proofread reports, books, journal articles, theses and dissertations for self-publishers, businesses, academics and students, focus on what you can do to solve their problems. These days, I work exclusively for self-publishing fiction writers. They’re preparing their novels for a crowded market full of discerning readers with the ability to leave critical reviews on Amazon. My job is to help them overcome some of the problems they’ll encounter on that journey, and my website focuses on that rather than on my politics degree. Did my politics degree help me when I worked exclusively for social science publishers? Perhaps. But I think my years of in-house publishing experience, marketing social science journals, helped more. When some years later I was proofreading a book for a well-known university press and Loïc Wacquant came up in the references but the diacritic in his first name had been omitted, I spotted it. It was my career experience that showed me the way, not my degree. You, too, can use your IT background to demonstrate your knowledge and experience to clients. But it will only be part of the story. Ultimately, your message will need to be about them – their problems, their concerns, their challenges … and how you are part of the solution. If you tell that story in a compelling way, you’ll build a brand identity that inspires trust and engagement, one that makes you stand out against your competitors, regardless what subject you didn’t read at university. And though you don’t want to work exclusively on IT-related material, don’t shy away from using that as your springboard. It’s what you know, what makes you special. No one’s going to hire me to edit an IT book. Why would they when they can hire someone who speaks the language and knows the subject like the back of his hand – someone like you? Specialize in what you know first. Diversify as the opportunities arise, and develop your brand identity as required. That way you’re playing to your strengths in the start-up phase. I hope that helps you on your journey. Good luck!

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

1 Comment

Writing about pain is hard, but there’s no shame in that struggle; it’s difficult to articulate even when we’re experiencing it.

‘Pain is […] the kind of subjective and poorly delineated experience that is difficult to express satisfactorily in language […] Indeed, pain shares some of the characteristics of target domains that have received considerable attention in the cognitive linguistic literature. Like LOVE, for example, it is private, subjective [...] cannot be directly observed,’ says linguist Elena Semino.

When researching this article, I was surprised by how little has been written about the art of depicting physical pain in fiction. And, yet, the act of hurting is prevalent in most genres; it deserves as much attention as emotional distress. I've come across a few examples in my sentence-level editing work this year where great writers came a little unstuck, tending towards repetition and overwriting the pain. That was my prompt to delve deeper. I thought it would be interesting to look at depictions of physical pain from within the bubble of novel craft ... and beyond, in medicine and poetry. Here are 5 tips to help you write about physical suffering. 1. Don’t always say it hurts – less is more ‘Pain is something we all go through to a lesser or greater extent. It’s something we all know intimately. Yet it’s so hard to describe and write about. It’s hard to push beyond “it hurts” and not wallow in it and also hold your reader,’ writes Justine Larbalestier. She’s spot on. It’s why some beginner writers’ pain scenes end up either repetitive, overwritten or clichéd. Trust your reader. If a character’s elbow is smashed with a hammer, do we really need to be told that it hurt, that he ‘writhed in agony’, that he was ‘wracked with pain’? Sometimes less is more. Readers are very good at filling in the gaps. Just as we imagine (without being directed to) a character rolling her eyes when she’s frustrated, raking her hands through her hair when she’s downcast, or biting her lip when she’s anxious, so we know that she feels pain when she’s kicked or punched, when she stubs her toe, when she’s stabbed, whipped or bitten. Mick Herron is a master of keeping it lean. It’s not that he avoids mentioning pain, but he weaves experience into its telling that makes the reader think, Yes, I get that. Here’s an extract from Slow Horses: Arms pulled River upright and his body screamed, but felt good at the same time – aching its way out of a cramp. A bottle was pressed to his lips, and water poured into his mouth. River coughed and bent forward; spat; threw up almost. Then blindly reached for the bottle, grabbed it, and greedily gulped down the rest of its contents. ‘Shit, man,’ Griff Yates said. ‘You really are a fucking mess.’

2. Consider the type of pain

Commonly understood descriptors can be useful when thinking about pain writing. Semino references the 1971 McGill Pain Questionnaire and summarizes author Ronald Melzack’s categorization as follows:

The first way in which you might use this table is to apply the descriptors to your writing of a character’s pain. These can help you with the shape and movement of it.

Here's a fine example cited by Susannah Mintz. It's a scene from Sharon Cameron's Beautiful Work, where the narrator, Anna, says of her pain: [It is a] beating between my breasts, and a reverberation of beating upward to my collarbone – a low steady hum, close to my body, not touching it. But agitating it. Below the beating, a thick, spikelike pressure was driving down to my belly …. The roof of my mouth was dry. I couldn’t swallow. A harsher beating arose near the surface of the skin in my left breast below the nipple. (84) The descriptors are evident, but Cameron uses them artfully to bring the pain to life; it has intention. It does things to Anna ... it's 'near' her, 'close to' her, rather than within her. In this detached state, the pain becomes a supporting character in the scene.

3. Focus on pain's consequences

Think about how you might show physical and emotional reactions rather than telling the pain. You could use the descriptors from the table above as nudges as to what those reactions might be. For example, if your character’s pain is crushing, you might express this by showing him struggling for breath; if it’s gnawing, you might have him bent and holding his belly. Back to the hammer and the elbow … what if instead of being told that the character is in agony, we learn that he doubles over, falls to his knees, vomits, or blanches? Perhaps he experiences a white-out, or loses control of his bowels. What about the sounds he makes … or those he doesn’t because he’s rendered voiceless? How does the pain move and what does it look like? Some of these reactions might be brutal, but the injury and consequent pain are themselves brutal and needn’t be shied away from. Similarly, emotional reactions can help with the writing of physical pain. How does your character feel when that hammer hits his elbow? Depressed, frightened, vulnerable, hopeless, despairing, humiliated, angry? In The Poppy Factory, William Fairchild focuses sharply on the sounds and movements his character makes, and shows the hurting through them. Then suddenly you're down and all movement stops like a jammed cine film. You're still screaming but now it's different. It's because of the pain and when you try to get up, your legs won't move. You don't know where you are. All you know is that you're alone and probably going to die. When you stop screaming and look up, the sky is dark and you can't hear the guns any more, only the sound of someone moaning softly. It takes a few moments before you realise it's yourself. In the PDF below, I've included some additional ideas for possible reactions to pain, (based on the nudges from the descriptor table above). There's space for you to add your own.

4. Acknowledge the limitations of agony

When I’m told that a character is in (physical) agony, my expectations of what she is capable of are changed. I’ve only been in agony a couple of times in my life, and I was good for nothing, rendered almost immobile. Reason left me. So did language. And so just because our protagonist is an MI5 agent with advanced armed-combat skills and interrogation-resistance techniques, there’s probably only so much she can take if she’s in agony. Some genres of writing lend themselves better than others to acute pain tolerance – fantasy and sci-fi, obviously, when world-building rules allow for it; and action/adventure with Jason Bourne-like characters who refuse to go down no matter what they’re subjected to. Somewhere there’s always a line, though – a point where Invulnerable Uberguy becomes unbelievable, laughable. If we’re told he’s in agony but he’s still throwing cool punches, turning roundhouse kicks, evaluating his escape route and planning this evening’s dinner date all at the same time, parody’s not far away. There’s nothing wrong with escapist writing that allows for agony tolerance and superhero-like brilliance as long as that’s your intention and your reader’s expectation. If you’re aiming for authenticity and grit, though, be mindful of pain thresholds, especially what’s possible when your character’s in agony. Agony, drawn realistically, can make us doubt the protagonist’s ability to make it. Why is that interesting? Says K.M. Weiland: ‘A good story should have the power to engage [readers] in a character’s suffering even when they know it’s all going to turn out right in the end. Every time an obstacle shows up between your protagonist and his goal, ask yourself: Is this just something that happens to him? Does he just brush it off and move on? Or does it hit him where it hurts? Does it make him (and readers) doubt his ability to make to the end of his journey?’

5. Look at how the poets do it

Milton. Who better? In this excerpt, we’re left in no doubt as to Satan’s physical suffering, and yet there’s no mention of his feeling it. Instead, we see it in our mind’s eye through the effort of his movements (‘uneasy steps’) and the detail in the environment (‘burning marle’, ‘torrid clime’, ‘inflamed sea’) that ‘he so endured’. His Spear, to equal which the tallest pine Hewn on Norwegian hills, to be the mast Of some great admiral, were but a wand, He walked with to support uneasy steps Over the burning marle, not like those steps On Heaven’s azure, and the torrid clime Smote on him sore besides, vaulted with fire; Nathless he so endured, till on the beach Of that inflamed sea, he stood and called His Legions, angel forms [...] Which is best? Whether you choose to leave your character's hurt to the reader's imagination, tell it through using commonly understood descriptors, or show it through reaction and environment will depend on your style, genre and intention. If you're in the middle of a fast-paced action scene, Cameron's approach in Beautiful Work might be a distraction for your reader. If you're writing a more introspective scene, Herron's lean approach in Slow Horses could leave the reader wanting. There's no best way of writing about physical suffering. The most important thing is that it shouldn't be boring. Unless your reader has congenital analgesia, they will have experienced pain and know it is anything but tedious. Further reading

Here's your Pain: Type, Shape and Reaction Nudges PDF. Click on the image to download your free copy.

Fancy a watch a video instead? Here is it.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Content marketing gives a lot of editors and proofreaders the willies. Too little time, too much work, don’t have enough ideas, can’t work out what to blog about, don’t even know what it is. Here's one silly idea to help you get to grips with it.

So when John Espirian and I agreed to lead a 2-hour workshop on content marketing at the 2017 Society for Editors and Proofreaders (now CIEP) annual conference in Wyboston Lakes, we assumed we’d have our work cut out for us.

How were we going to convince a room full of wordsmiths that content marketing is valuable, doable and enjoyable? To cut a long story short, we asked them to throw their split infinitives, comma splices, dangling modifiers and restrictive clauses out of the window for 120 minutes and have a bit of fun with us. Did they rise to the challenge? You bet!

The problem with marketing

Every business owner needs to do marketing. And if you love it (like I do, like John does) that’s great. But what if you find it a bore? What if you’re someone who prefers the work you do to the work you do to get the work you do? Still with me? Editors and proofreaders are just as time-poor as anyone else. Marketing takes time and effort. And content marketing requires commitment because you won't see the impact overnight. One of the best things about content marketing, though, is that it’s ripe for playfulness. And that’s the case whether you’re doing it or learning to do it. That playfulness must be on-brand, of course, but creating useful, helpful, valuable content that solves clients’ problems needn’t be a dull process if you keep an open mind. John and I asked our colleagues to open their minds and go a little bonkers. And if you think you can’t do content marketing, perhaps you can try this exercise too.

The Whacky-business Workshop (or how to develop a content marketing mindset)

We spent the first hour on the why and what of content marketing so that our friends understood the principles that underpin the approach. And just in case you don’t know, content marketing is basically about creating and delivering useful stuff that inspires people to trust you, engage with you, even buy from you. Next, we asked them to get into groups of two or three. Then we handed them a list of businesses and asked them to choose one. And so began the Whacky-business Workshop. There were no businesses related to editing and proofreading, mind you. None of the jobs in that list is something any of us has ever done; some of them aren’t even real, though not many. Instead, we gave them a list of whacky businesses – that way, our delegates would be forced away from their existing editorial business focus, and free to embrace a content marketing mindset. Here’s what they had to play with:

20 minutes to think, 1 minute to present We asked them to think about what problems those companies’ potential customers or colleagues would have – what they might ask before they decided to engage with or buy from one of those businesses – then generate as many content ideas as they could in 20 minutes. There were 2 rules:

Those who made our bellies ache the most would receive a chunk of content marketing goodies – well, books; we are editors, after all – written by industry experts.

Why does being silly help?

If you can take everything you’ve learned in an hour, apply it in 20 minutes, and generate a framework of solutions in 60 seconds – and with a company and customers you know nothing about – what might you do if:

Believe me, if you can generate 10 questions that a client might ask before hiring a human scarecrow, 3 videos about the benefit of fart-reduction underpants, or 6 reasons to hire a professional mermaid – in the time it takes to bake a cake – coming up with ideas for a year’s worth of content for your editorial blog, vlog or podcast will be a walk in the park. And our session proved it. Our colleagues were amazing. Some were content marketing novices when they walked into the room, others were looking to hone their skills, but all of these perfect punctuators, grand grammarians and artful amenders slipped easily into the shoes of their new businesses … and their audience. Of course, there can only be one winner … well, two in this case: our friends and fellow pro editors Kate Haigh and Kia Thomas. If you’re seriously thinking about setting up as a human scarecrow and you need help with your marketing strategy, just call them.

Some might think it’s difficult to make straw interesting, but Kate and Kia know different. Here's the content marketing magic they came up with in only 20 minutes:

Company name Outstanding in the Field – Human Scarecrows! Content aim To make our website a valuable resource for other human-scarecrow professionals Content ideas – solving potential clients' and colleagues' problems

Editors are born content marketers

It's true. Editors and proofreaders are problem solvers by nature. We spend our working days finding problems and working out how to fix them … not with blunt force but with elegance, with respect, with our writers in mind. We query kindly, we tweak tenderly, and we never forget that if our clients don’t have problems, we don’t have jobs. And that’s pretty much what content marketing is all about – identifying problems, offering solutions, and doing so in a way that makes the potential client trust you. So if you think you can’t do it, that it will be too hard, will take too much time, that you won’t have enough ideas, that you’re an editor not a marketer, then try being silly. Pick one of those whacky companies and ask yourself what you’d want to know before buying from them. Turn those queries into a list of ideas for blog posts, videos, PDFs, infographics, booklets or podcasts. There are no rules – you’re just having fun. When you’re done, think about your editorial business and your clients. What are their problems? And how might you create and deliver the solutions? No problem is too small, and no question too basic. If you’ve thought of it, chances are there’s a potential client who’s thought of it too. Why not be the one to fix it and have that solution on your website? If you have a question about content marketing for an editorial business, drop me a line or leave a comment. I’ll do my best to help … unless it’s about human scarecrows. In which case, you know who to call. More resources

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

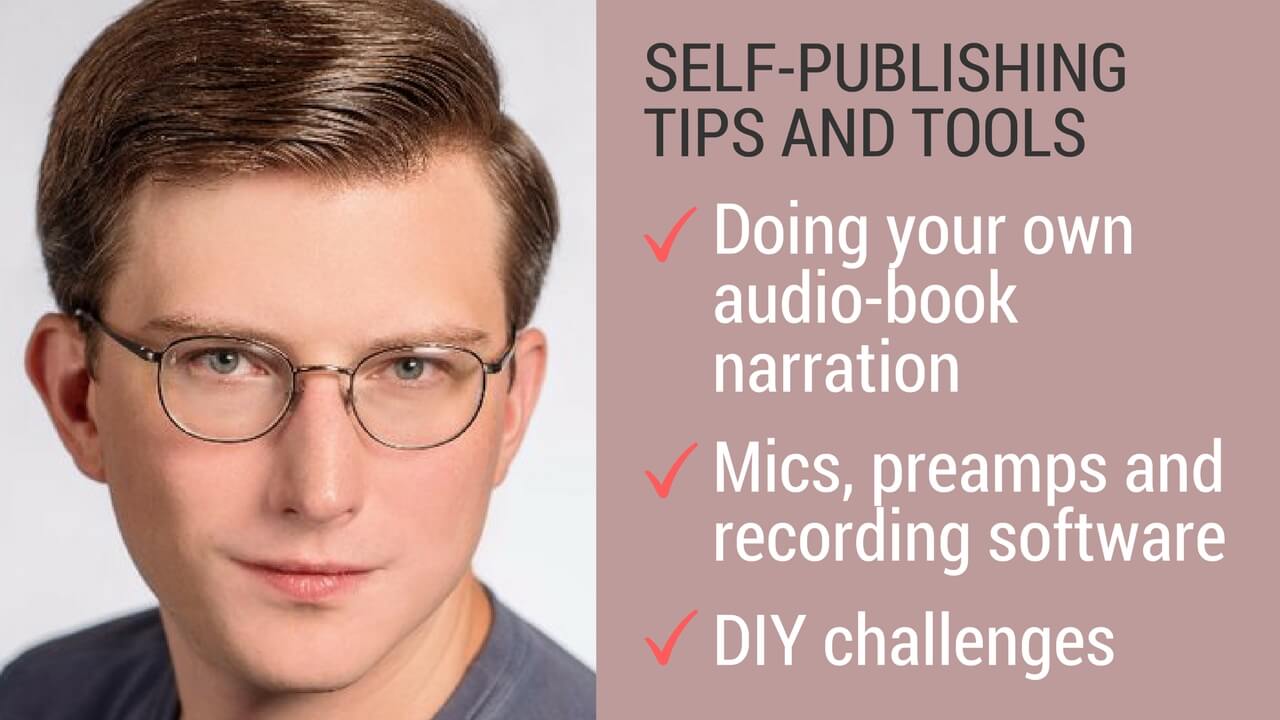

Here's more from my audio-book creation series. This time, professional voice artist Ray Greenley talks about doing it yourself, how long it will take and what kit you'll need. Over to Ray ...

In previous posts I talked about platforms (ACX), pricing, and sourcing and evaluating a professional voice artist for your audio book.

I know what you're thinking – 'There’s another option you’re not telling me about on purpose … I could avoid all these issues and just record my book myself!’ Yes, that’s true. You could. Okay … are you sure? I mean, REALLY sure? Because producing an audio book does take quite a bit of work. As a rule of thumb, a producer who knows what they’re doing will generally spend about six hours working to produce a single hour of finished audio. So if your audio book ends up being about 10 hours long, that means you could expect to spend about 60 hours working to produce it once you’ve invested the time in learning how, and the money in the equipment you’ll need. You'll need the following equipment (I'll go into more detail below):

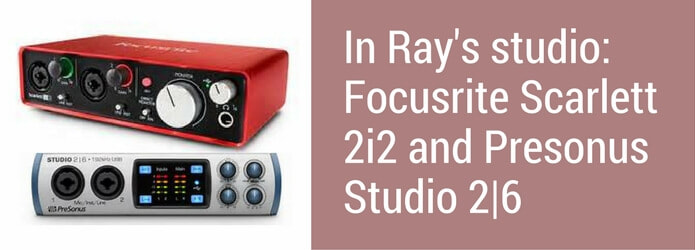

There are some decent microphones that plug directly into your computer via USB, but generally you’ll get a better sound with an XLR microphone and a preamp.

Also, vitally, you’ll need a good space to record in. It should be quiet with plenty of sound-absorbing material in it to make the space sound as ‘dead’ as possible.

A walk-in closet can do the trick in a pinch, although chances are you’ll need some additional sound treatment to really get it acceptable. By the way, if you live in a busy area with a lot of traffic or other outside noises that you can hear from your space, then your space is no good unless you can somehow insulate against all those outside noises or are willing to record in the middle of the night when (hopefully) things are quiet. More on preamps and recording software Okay, well if you’re really on a budget, you can record using Audacity, which is free recording software. It has some solid tools and can do what you need. If you’re willing to invest some money, you can get some reasonably priced software that can do a bit more. I use Studio One Artist from Presonus, and I know some other narrators work well with Reaper. Both of those programs can be had for less than $100. There are many others as well.

For the preamp, there are some good options at a reasonable price. I currently use a Focusrite Scarlett 2i2, but I’m looking forward to upgrading to a Presonus Studio 2|6 soon.

Another reasonable option would be the Presonus AudioBox USB. One of the nice perks to getting one of the Presonus preamps is that it includes the recording software I mentioned earlier, Studio One Artist. Once again, there are lots of other options, many of which would probably be sufficient for your needs. The big question, the microphone So I can tell you that I use a Shure KSM32 and it works well for me. I’m pretty fortunate that I can sound good on such a relatively inexpensive microphone (US$499+).

Unfortunately, there’s absolutely no way to know if YOU will sound good on it, too.

Microphones really are very personal tools. One that works great for me might be terrible for you, and vice versa. Your best bet is to try several out and see what works well. The easiest way to do that is to find a specialty store that sells them; the store will often let you try some out before you buy because they’re aware of the difficulty in matching the microphone to the voice. ‘Okay, so once I’ve that all set up I’m good to go, right?’ So … no, not nearly. You still need to learn how to USE all that stuff, which takes a lot of time and effort.

I know this isn’t a surprise coming from me, but I think you’ll REALLY want to consider carefully when it comes to narrating your own book.

If you think you might really want to get into narration and put in the time and energy to learn how to do it right, then have at it. It’s very challenging work, but also very rewarding. There are very few people who have the right talents to be both a writer and a narrator, let alone have the time to train and use both sets of skills. My hat’s off to you! However, if you’re thinking you want to record your own book because you just want to try to save some money over paying a narrator to do it, or hoping to avoid the work of finding a good narrator who’ll take your book on as a Royalty Share project … please don’t. I promise it’ll take time you’d probably rather spend writing, and the chances of it really being a high-quality production are not great (no offence). In the long run, I’d bet it will cost you more than you’ll save, one way or another.

Next time we'll be looking at distribution, briefing the artist, and evaluating the first 15 minutes. Until then, thanks for reading!

Resources

Contact Ray Greenley Website | Facebook | Twitter

To read the 26-page primer in full now, visit the book's page: Audio-Book Production.

Louise Harnby is a fiction copyeditor and proofreader. She curates The Proofreader's Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. If you're an author, you might like to visit Louise’s Writing Library to access my latest self-publishing resources, all of which are free and available instantly.

The Begin Self-Publishing Podcast is dedicated to sharing tools, tips, advice and ideas about self-publishing from industry specialists.

The BSP host, Tim Lewis, kindly invited me onto the show to talk about fiction editing. Tim and I discuss the following:

You can listen to the full episode here: Fiction Editing with Louise Harnby Previous episodes have addressed non-fiction editing (with my friend and colleague Denise Cowle), business tips, marketing advice, social media promotion, cover design, interior formatting and publishing services. For more information, or to subscribe, go to the Begin Self-Publishing Podcast.

Louise Harnby is a fiction copyeditor and proofreader. She curates The Proofreader's Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. If you're an author, you might like to visit Louise’s Writing Library to access my latest self-publishing resources, all of which are free and available instantly.

My friend and colleague Denise Cowle is a specialist non-fiction editor who works with a wide range of businesses, so she understands the pressure to publish better than most. Here's her expert advice on when good enough is acceptable ... and when it's not.

Perfection and the pressure to publish

When you write for your business, is it perfect? Should it be? Small businesses without the benefit of a dedicated marketing department are increasingly recognizing the power that quality content has to raise their profile, connect with their potential clients and ultimately drive sales. However, the focus on publishing content regularly can pile on the pressure to get something – anything – out there, to keep up with the publishing schedule for your blog, or to update your web copy and marketing materials to reflect the latest developments in your field. Does this writing have to be perfect? Should we expect everything that people produce to be error-free? If you pay too much attention to the Grammar Police, you’ll be paralysed with fear that a misplaced apostrophe or misused word will bring your carefully constructed business crashing down around your ears. There’s no excuse for poor grammar, they’ll bellow, caps lock on, from behind the anonymity of their screens. Ignorance of correct spelling is the scourge of society, they’ll mutter, labelling you as feckless, careless and lazy, without knowing anything about you or your business, other than the fact you typed except instead of accept. But as an editor, and advocate of content marketing, I beg to differ. I think there are occasions when it’s OK to put out content with errors. Shock! I know! Am I doing myself out of a job here? Not exactly.

This is not permission to abandon all standards

Before you go rushing off to dispense with the services of your freelance editor and disable spellchecker, let me explain. I’m not for a minute suggesting that you should take this as permission to abandon all efforts to produce great, error-free copy. I’m working on the assumption here that you’ve taken time to make your copy the best it can possibly be within your time and budgetary constraints. I’m assuming you’ve used the tools and techniques available to you; you’ve run the inbuilt spellchecker or other software, read through your text carefully, and used a dictionary when you’ve been unsure. But sometimes, despite all your efforts, errors remain, either because you’ve missed them or because you don’t actually recognize them as errors in the first place. You go ahead and hit the publish button, and your mistakes are out there for all the world to see. We’ve all done it, but it’s rarely the end of the world. When is it OK to publish content with errors? In my view, it’s forgivable to have the odd mistake in content that:

It comes down to the purpose of the content, the medium you’re using, and the value your audience places on it. Your reputation will survive a typo in a tweet signposting your latest blog (I’ve done it myself and lived to tell the tale). Unless, of course, the typo is so unintentionally funny or rude that it goes viral! And even then, is there such a thing as bad publicity? It depends on your business, and what the error is. If you’ve created a free email course as lead generation I’d expect it to be error-free. However, the odd missing apostrophe or spelling mistake may not be a deal-breaker for your audience if the content is amazing and provides lots of value.

When is it not OK to publish content with errors?

It’s not OK to publish content with any errors if:

If you’re an editor or proofreader, to my mind this is a no-brainer. Your clients are looking for perfection, or as near as dammit. There is no margin for error here. And don’t think you can get away with proofreading your own writing because, let me say this clearly: You. Will. Miss. Things. Who wants to hire an editor with spelling or grammatical errors in their copy? The answer should be: no one.

Banish procrastination and publish!

No one wants to see any writing, however fabulous the content, strewn with spelling mistakes and grammatical blunders. But I’d much rather see you sharing your content with the world than keeping it in a draft folder because you’re worried that it might contain errors. Don’t allow fear to prevent you from publishing. Do your due diligence – run spellchecker, follow my tips on how to proofread your own writing – and get it out there! The world doesn’t stop turning because of a couple of typos, and you owe it to yourself and your business to write that copy, making it as good as you can. Should you hire someone to edit/proofread blog posts or other content? Rather than slogging over copy like it’s your overdue English homework, you might recognize that your time is better spent elsewhere and free yourself from the burden. If writing isn’t an enjoyable part of your work, wouldn’t it be better to outsource all or part of the process? Giving yourself permission to do this acknowledges that your time is a commodity in your business, and you have a responsibility to spend it wisely. You should consider this option when:

Is good enough, enough? Not everyone is blessed with the ability to write well and consistently, but I believe that everyone can improve with practice. Learning from mistakes is a crucial part of the process, and that can only happen when you write your web copy or publish your blog and allow other people to read it. Good enough can be enough when it’s on the road to even better.

Denise Cowle is a copy-editor and proofreader for non-fiction. She works with educational materials, reports, marketing copy and blogs. Her blog focuses on helping you to be a better non-fiction writer. Denise is an Advanced Professional Member of the Society for Editors and Proofreaders.

Further reading from Denise

Louise Harnby is a fiction copyeditor and proofreader. She curates The Proofreader's Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. If you're an author, you might like to visit Louise’s Writing Library to access my latest self-publishing resources, all of which are free and available instantly.

Are you fed up with your 404 page? Worried that your clients are too? Broken links are broken conversations. Here’s a wee idea I came up with to fix the disappointment and get you and your visitors talking again … using a chatbot.

What is a 404 page?

A 404 page is where your visitor ends up if they’ve clicked on a link to your website and one of the following has occurred:

Google’s recommendations for a high-quality 404 page

404 frustrations

When you hit a 404 page on a website, you feel frustrated. You’ve gone to that site for a reason – you’re trying to solve a problem, or learn something new, perhaps even buy a service or product. And if the page you’re searching for has been moved, or if the link you’ve clicked is incorrect, you end up in a place you don’t want to be. It’s a dead end. If the website’s owner has been thoughtful, there’ll be a search box or menu to help you, perhaps a list of links that might be useful. Still, you’re the one who has to do the work to get back on the right path because, usually, there isn’t is a way of talking to the owner, a way of saying, ‘I wanted X but I’m stuck. Can you help?’ And since you’re already in a grumpy mood, you’re more likely to disengage and leave the site. After all, someone else is probably solving your problem, and maybe if you head back to Google Search, you’ll find a fix rather than a 404.

A beautiful bot! Introducing Lulu …

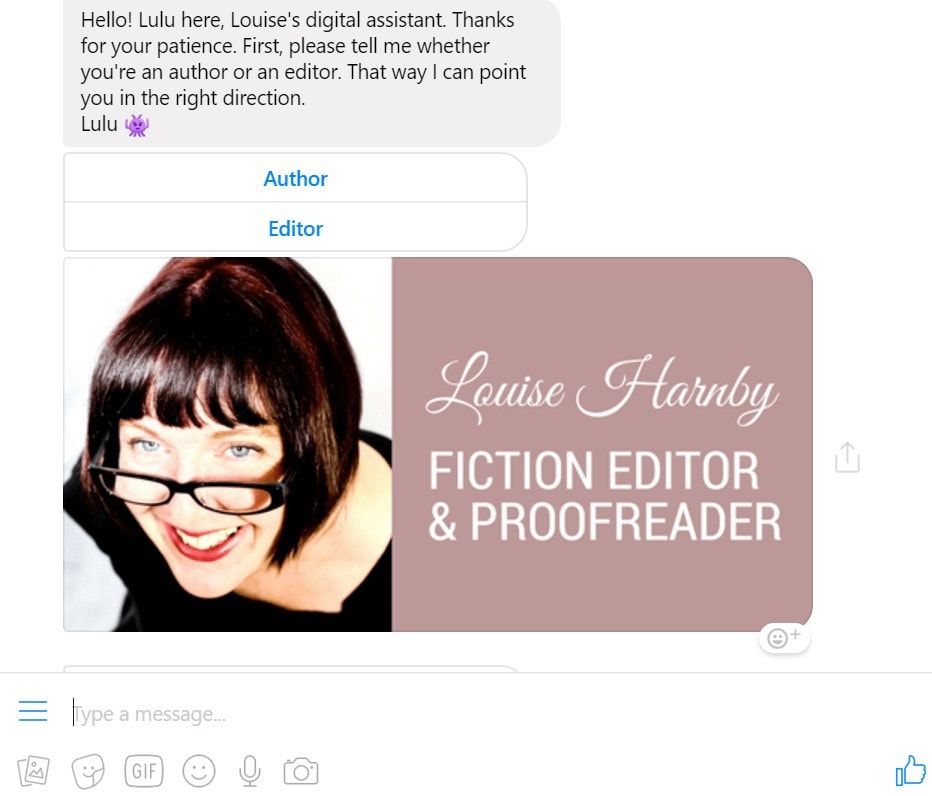

I’m a fiction copyeditor and proofreader and I love marketing my business! I regularly publish free booklets, PDFs, checklists and templates for fellow editors and proofreaders, and self-publishing authors. I share news about that content via social media and on my blog. A few weeks ago, I set up a free account with ManyChat. I created Lulu, my Messenger bot. She’s my digital assistant and she’s great – most of the time! We’ve had a few glitches … some digital napping on the job … but in the main she’s successfully helped me deliver my resources to my Facebook network. Instantly. I learned how to build Lulu from my two favourite pro content marketers Andrew and Pete. August was their ‘Build Your Bot Month’ and four in-depth tutorials taught me everything I needed to know to get going. If you want a taster, hop over to YouTube and watch ‘Get Started Using Messenger Bots in Your Marketing with Andrew and Pete’. All well and good. But was there other ways I could use Lulu to help me engage with my community of editors and authors meaningfully? Recently, I was looking for something online. It took a while to find what I wanted, but find it I did. Or nearly. The link looked good but landing was a disappointment – a 404. The site was busy and I had no clue where to start. So I did what a lot of people do online. I gave up and went somewhere more interesting instead. That’s not what I want people doing on my site. I want my authors and colleagues to feel that I’m there for them, ready to help, ready to engage. Could Lulu help?

The ManyChat webpage widget

I decided to get Lulu on the case of my 404 page. I have a lot of content on my website, and even more external links to that content. I’ve been blogging regularly since 2011, and I’ve changed things around on my site more times than I care to mention. And while I do my best to set up 301 redirects when I make changes, there’s no doubt that there are external broken links about which I can do little. ManyChat has a bunch of growth tools including two embeddable widgets. One is an opt-in box that can be placed anywhere on a website. I’ve used this widget to provide a more interactive experience for my 404 arrivals, one that enables them to make choices with the click of a button, but ultimately to say, ‘Louise, I wanted X but I’m stuck. Can you help?’ Because they’re contacting me via Messenger, they can get in touch instantly. Which means I can help them quickly. And the quicker I help, the less likely they are to get the hump and go somewhere more interesting instead. What’s great about this widget is the customization element. You can choose colours, images and messages that reflect your clients’ needs and your solutions. It matters not whether you're an editor like me, or an author, or another type of business owner ... the widget will work for anyone with a website.

Case study: the visitor journey on my 404 page

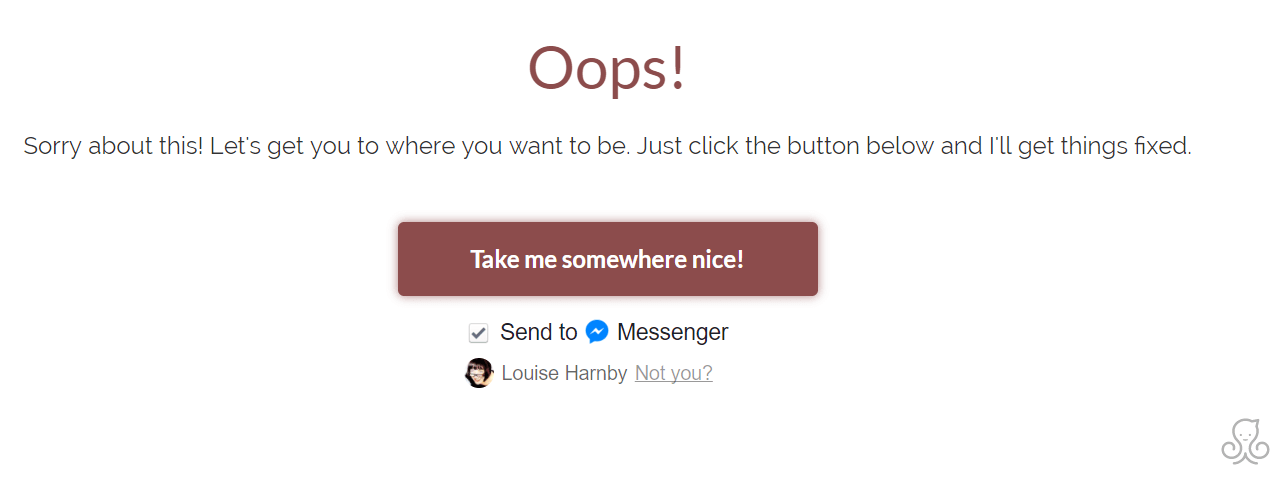

Now that I’ve set up Lulu, the visitor who lands on my 404 page can take a journey, one that involves the ability to interact directly with me quickly. Here’s what it looks like ... This is what the visitor sees when they land:

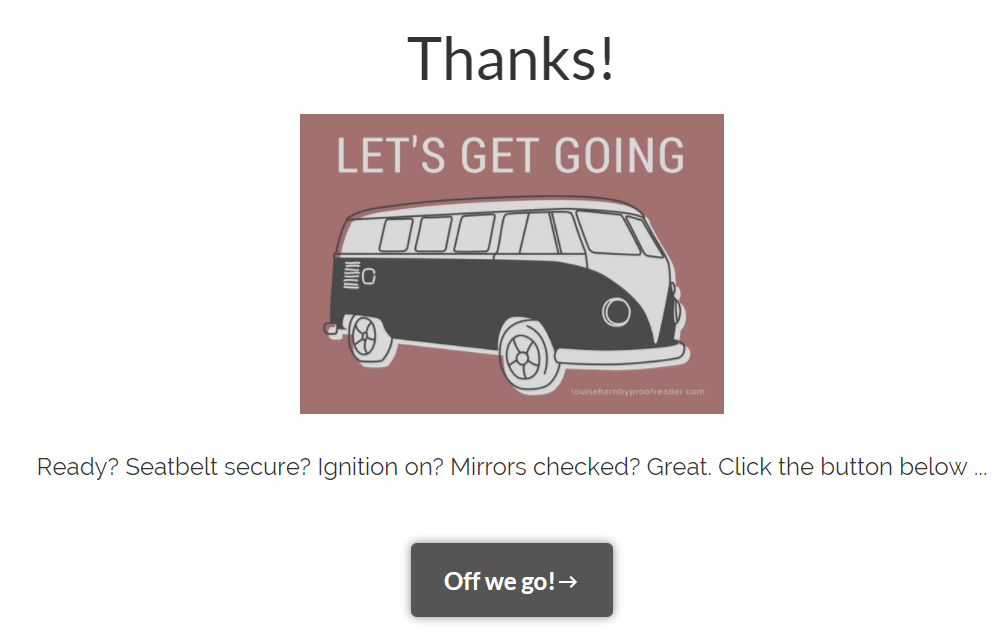

Clicking on the button takes them to a new page:

Now the conversation beings in Messenger. First, Lulu introduces herself and asks the visitor to provide some information that will determine how the interaction proceeds:

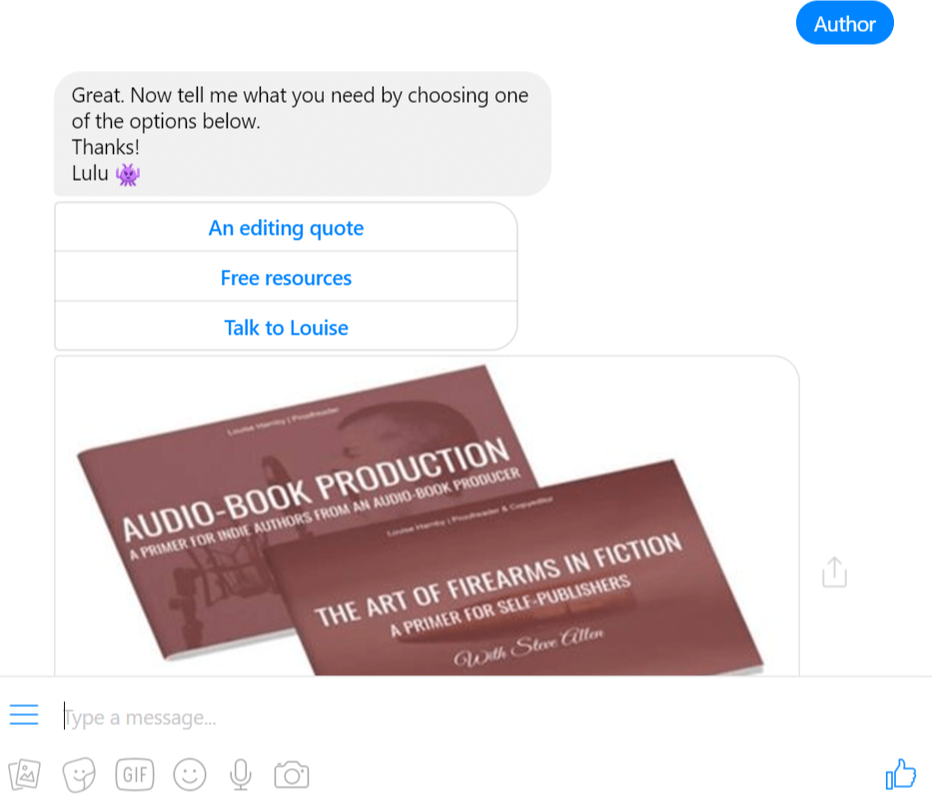

In this example, the visitor has selected ‘Author’. This generates a new set of choices, including the option to have a conversation with me:

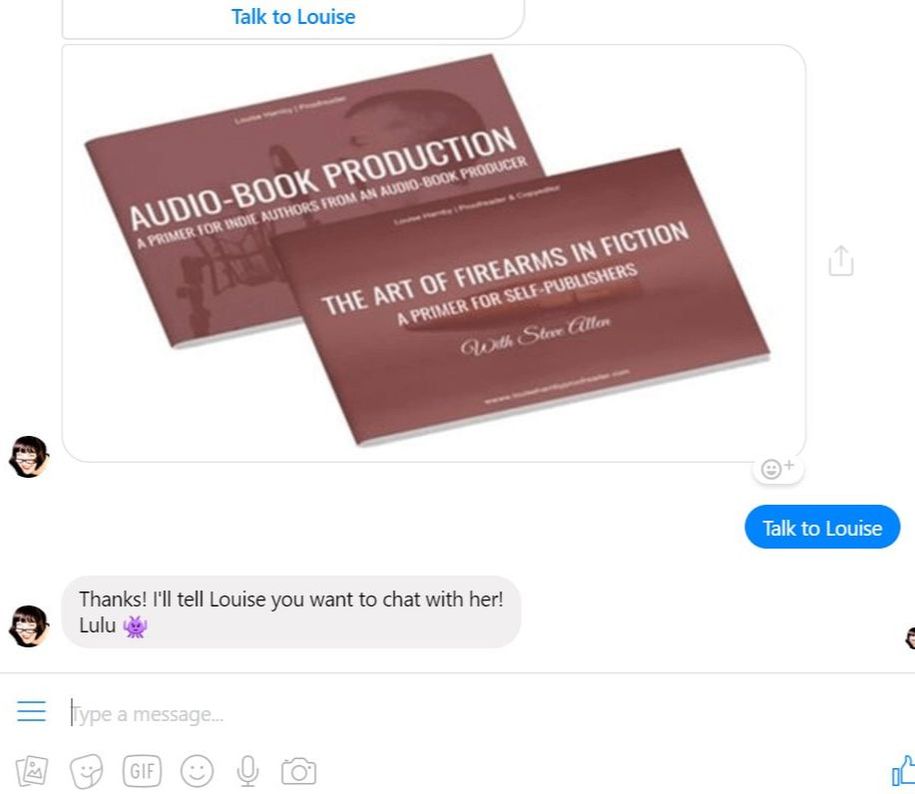

If the visitor chooses to ask for a quote or get some free resources, they’re taken directly to the relevant pages on my website. If they wish to talk to me, Lulu acknowledges the request with a message:

In the Messages section of my Facebook page I receive a notification that someone wishes to chat. Lulu steps aside and the real conversation with me can begin:

Summing up

The ManyChat widget allows us to work with Google’s recommendations: apologetic, friendly language that acknowledges the problem; colours, language and images that are on-brand; clickable links to key pages and core content; and the ability to report the problem directly via an instant conversation. Landing on a 404 page is a negative experience for the visitor. A chatbot turns that negative experience into an opportunity, one that offers a series of calls to action. By including a discussion in the mix, we can offer one-to-one engagement. And it’s fun! We’re putting a smile back on a frustrated client’s face, and that can only be a good thing! Have you used a chatbot for your own 404 page, or as a way of engaging with your clients and colleagues? Let me know in the comments!

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Slipping into character – understanding the impact of narrative point of view (Sophie Playle)7/9/2017

Point of view can be difficult to master if you've not studied novel craft. My friend and colleague Sophie Playle has. She's an outstanding developmental editor who knows how to help writers get the big-picture stuff right. Today, she takes you through the fundamentals of narrative point of view so you (and your reader) know who's telling your story.

Over to Sophie ...

As an author, you have a lot of decisions to make when it comes to putting the ideas you have for your novel down on paper. Where should you start the story? Which characters should you focus on? Should you write in past or present tense? Third or first person? The possibilities are overwhelming.

It seems counterintuitive, but narrowing your options can be quite freeing. Once you’ve eliminated the paralysis of infinite choice, you can focus your creativity. Choosing the viewpoint from which you tell your story is one decision you should certainly consider. It doesn’t matter whether you think about this before you start writing or during the redrafting stage. Either way, by deliberately and purposefully aligning your narration with a particular character, you’ll be able to:

When a novelist hasn’t considered the point of view from which they’re telling their story, it makes things a lot harder for the reader. The story might lack focus, the characters might feel at arm’s length, and the writing style could fall flat. If you struggle with any of these issues, considering point of view could be the answer.

What is ‘point of view’ in fiction?

Let’s start with the basics. When we talk about point of view in fiction, we’re talking about the position from which the events of the novel are being observed or experienced. It’s essentially where you’ve decided to place the lens through which a reader accesses your story. [My writing] students talk about 'point of view' […] as if it were mechanical, when in fact it refers to the hardest and most thrilling thing we do—becoming someone else, becoming that person so thoroughly that if we’ve decided the person is nearsighted, we’ll imagine the room in a blur as soon as she takes off her glasses; if we’ve made him so jealous he can kill, we’ll feel mad rage down to our tingling fingertips when his girlfriend looks at another man.

Alice Mattison, The Kite and the String

But before we get into the details of slipping into character, we should back up a little. There are many narrative layers to a novel, and it’s useful to understand them.

Narrators, not authors, tell stories.** The difference is subtle, but important. If the author tells a story, the reader knows it’s made up. But if the narrator tells the story, it’s much easier for the reader to willingly suspend their disbelief and immerse themselves in what the narrator is saying. When you write, you – as the author – should disappear. Instead, you channel the narrator. The narrator can either be a character in the story or a disembodied observer. Either way, you see what they see, hear what they hear, and smell what they smell as they experience the events of your story. And depending on the type of narrator you’ve chosen to use, the narrator can also slip in and out of the perspective of your viewpoint character (or characters), experiencing the world through their body and mind, expressing those experiences using their language and style. I admit, it’s a little confusing to wrap your head around. So let’s take a quick look at the most common types of narration and the implications each can have on your writing, and hopefully all will become clear.

The different types of narration

FIRST PERSON First-person narration is when a character is telling the story from their own perspective and uses the pronoun ‘I’. Unless the character is telepathic, they will only be able to express the events of the novel from their own point of view and have knowledge of things only they have experienced. If they learn things from other characters, this knowledge will be filtered through (and potentially distorted by) their interpretation. Pros

Cons

EXAMPLE: If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you'll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don't feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth. In the first place, that stuff bores me, and in the second place, my parents would have about two hemorrhages apiece if I told anything pretty personal about them.

J. D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye

THIRD PERSON OBJECTIVE

Third-person narration refers to characters as ‘he/she/it’. Third person objective is used when the point of view from which the story is told is like a floating camera following the characters around. The narrator is almost invisible as it won’t express any thoughts and emotions and can only report on sensory experience – what could be seen, heard or smelt by any onlooker. There is no direct access to the thoughts and emotions of the characters, other than what can be interpreted by their dialogue and actions. This viewpoint isn’t normally used over the course of a whole novel, and it can be blended with third-person subjective (see below). Sometimes new writers will inadvertently use this viewpoint if they’ve taken the advice ‘show, don’t tell’ to an ill-considered extreme! Pros

Cons

EXAMPLE: Spade rose bowing and indicating with a thick-fingered hand the oaken armchair beside his desk. He was quite six feet tall. The steep rounded slope of his shoulders made his body seem almost conical—no broader than it was thick—and kept his freshly pressed grey coat from fitting very well. Miss Wonderly murmured, “Thank you,” softly as before and sat down on the edge of the chair’s wooden seat.

Dashiell Hammett, The Maltese Falcon

THIRD PERSON SUBJECTIVE (OR LIMITED)

Unlike with third person objective, the reader has access to the thoughts and emotions of the viewpoint character. The story is told only through one viewpoint character’s perspective at a time. We see, hear, smell, taste, feel and think what they do; the narrative is written in the character’s voice; and the reader can know only what the character knows. Third person subjective narration can be blended with third person objective narration to varying degrees. If the narrative is slightly more objective, the character’s direct thoughts might be made visually distinct from the main narrative by either being presented in italics or quote marks; if the narrative is very much subjective, separating direct thoughts isn’t necessary because the whole narrative is written from the direct perspective of the character. Jumping from one viewpoint character to another in close succession is known as head hopping and can be very confusing for the reader. It’s advisable to stick to one viewpoint character at a time. Pros

Cons

EXAMPLE: It was almost December, and Jonas was beginning to be frightened. No. Wrong word, Jonas thought. Frightened meant that deep, sickening feeling of something about to happen. Frightened was the way he had felt a year ago when an unidentified aircraft had overflown the community twice.

-- Lois Lowry, The Giver

OMNISCIENT

With omniscient narration, the narrator knows everything and isn’t limited to the viewpoint of any single character. An omniscient narration could be written in present or past tense, and use first or third person; they could be a character in the story (like a god or an enlightened person), or they could be an observing nonentity. Completely omniscient viewpoints are difficult to pull off well and have fallen out of fashion. Pros

Cons

EXAMPLE: Margaret, the eldest of the four, was sixteen, and very pretty, being plump and fair, with large eyes, plenty of soft brown hair, a sweet mouth, and white hands, of which she was rather vain. Fifteen-year-old Jo was very tall, thin, and brown, and reminded one of a colt ... Elizabeth – or Beth, as everyone called her – was a rosy, smooth-haired, bright-eyed girl of thirteen, with a shy manner, a timid voice, and a peaceful expression, which was seldom disturbed ...

— Louisa May Alcott, Little Women

Omniscient narration is quite complex, so let’s go into a little more detail. Omniscient narration can never truly be all-knowing because of the limitations of the nature of writing and reading: words must be read in order, so experiences must be felt in a linear way, which is not the same as having all knowledge in your head simultaneously.

Because of this, as with all writing, the issue is that of choice: what information does the omniscient narrator choose to divulge at any given time and, more importantly, why? Jumping from one viewpoint character to another (head hopping) should still be kept to a minimum to avoid confusion, and using an omniscient narrator is not an excuse for using this device in an uncontrolled way!

How to choose the right viewpoint for your novel

Choosing which type of narration to use will depend on the kind of effect you want to create, and the kind of knowledge-handling your plot requires. When deciding which point of view to choose, ask yourself the following:

These might not be simple questions to answer, but if you can figure out which answers are most important to you, you should be able to decide which narrative form and which character’s or characters’ viewpoints will allow you to tell the type of story you want to tell. How to control the POV in your story Once you’re aware of the issues of point of view, it’s surprisingly easy to control it and avoid confusion and inconsistency. All it takes is a little logical thinking, depending on your answers to the following questions:

Once you’ve answered these questions, it should be simple to use your chosen viewpoint in a consistent and focused way. How to handle multiple viewpoints Should you have multiple viewpoints in your novel? It’s really up to you – and will depend on the type of story you want to tell and the effects you want to create. The main advantage of sticking to one viewpoint is that it allows you to explore it in greater depth; the main advantage of using multiple viewpoints is that it allows you to explore the events of the novel in greater breadth. Switching the POV often makes it harder for the reader to really get to know a character. It’s the equivalent of going to a party and talking to a different person every twenty minutes. My advice is to keep your number of viewpoints to a minimum. Use only what the story needs – not what you feel like writing. If you have two narrators or characters telling the same story, you need a very good reason for it. When using multiple viewpoints, it’s imperative to make the switch between them seamless and clear. It’s best to start a new chapter or scene when switching viewpoints; at the very least, start a new paragraph. Whichever method you choose, keep the pattern consistent. Don’t just have one chapter in which there are multiple switches when all your other chapters stick exclusively to one viewpoint. Summing up The way you chose to narrate your story will have an impact on how your story is read. Different narrative styles allow you to create different effects. Choosing viewpoint characters brings focus, tension and originality to your writing. Controlling the point-of-view elements in your novel and learning to slip into character is one impactful way to become a better writer and write better books.

Further reading from Sophie

* One crucial thing you probably didn't realize about point of view ** Whose story is it anyway? How to choose your narrator

Sophie Playle runs Liminal Pages, where she offers editorial services to authors and training to fiction editors. Want a freebie with absolutely no strings attached? Sure thing. Click here to download ‘Self-Editing Your Novel’.

Louise Harnby is a fiction copyeditor and proofreader. She curates The Proofreader's Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. If you're an author, you might like to visit Louise’s Writing Library to access my latest self-publishing resources, all of which are free and available instantly.

If you're proofreading final designed page proofs, there's more to look out for than the odd typo or double space. Professional proofreaders identify and find solutions to a range of layout problems too.

This post featured in Joel Friedlander's Carnival of the Indies #84

.

Who's this checklist for? This is for anyone checking final designed page proofs. For example:

I've proofread over 500 books for the mainstream publishing industry. The checklist below is based on the house guidelines provided by the publishers I've worked for. The titles I've proofread include social science textbooks, handbooks and monographs, and works of fiction and narrative non-fiction. And while the subject matter has varied, the requirements for checking final page proofs hasn't. Note my use of the term 'final designed page proofs'. This checklist is not for those doing a final quality-control check in a Word document. Rather, we're dealing with a typeset PDF or hardcopy of the book as it will appear when printed or published online. For that reason, the proofreader is tasked with ensuring that the appearance of the book is consistent and correct according to client preference. This PDF provides a summary of the required checks. To get a free copy, sign up to The Editorial Letter, monthly news about fiction editing and editorial business growth.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Should you invest several hundred pounds in professional proofreading and editing training when there are free online courses available? A reader asked me whether the freebies are worth their salt …

Malika asked:

Hello Louise. Your blog has helped me with a lot of things. However, I am currently doing a BA. I want to learn editing and proofreading side by side. I wanted to ask whether the websites providing free online courses on editing and proofreading are reliable. Thanks for your question, Malika! Foundational English-language skills First, I always recommend that those considering a career in this field focus on their language skills before they embark on professional editorial training. Professional proofreading and editing courses teach the practice of how and when to amend or annotate. They assume an existing above-average knowledge of spelling, punctuation and grammar that accords with English-language convention.

Proofreading and copyediting – what do those terms mean?

Before I get into the nuts and bolts of your question, I’d like to talk about what’s meant by the terms ‘proofreading’ and ‘editing’. The terminology is often tangled. I define the various stages of editing as follows:

The training we do (whether it’s free or charged for) needs to reflect the skills needed to carry out these levels of editing. At the end of this post I've provided a PDF that offers more detail about the problems proofreaders and editors aim to solve at each stage.

Reliability, promises and intention

Now to your query. I think that an evaluation of a course’s reliability needs to ask two questions:

EXAMPLE The course:

Your intentions:

The course has been designed to help Purdue students with the thesis-writing process, not train proofreaders to professional standards. The course is reliable in the context of its intention. It’s just not a good match for you or anyone else seeking to set up an editorial business.

Client perceptions and expectations

There’s a marketing issue at stake, too. However ‘reliable’ the free course is, it’s worth asking yourself whether it has the potential to enhance or damage your trustworthiness. Here’s the problem – there are thousands and thousands of editors and proofreaders online. The market is global, too, thanks to the internet. If a client finds you and five others, how will they decide who’s worth getting a quote from? Imagine your home needs rewiring. You’ve already had one small electrical fire and want to avoid a future catastrophe. Who do you hire? The professionally accredited electrician or the spark who did a free tutorial on YouTube? People searching for editorial services are just as discerning. They’re handing over hundreds, even thousands of pounds to a stranger. They want a professional who’s passionate about their business, takes it seriously enough to invest in high-quality training, and knows how to fix what’s wrong to industry-recognized standards. If you can’t demonstrate that you’re that person, you won’t be able to compete effectively. Some client types, publishers for example, expect an editorial pro to have completed courses from specific training providers. Others will focus on your successful completion of a test. To pass the test, you’ll need to know your stuff. If your free course doesn’t provide you with the required knowledge, you’ll come unstuck.

Ask colleagues, clients and professional organizations

Some years ago, I asked a group of UK publishers about professional training. You can read what they said in ‘Does training matter?’ (see ‘Further reading’ below). If you’re based outside the UK, call a few publishers and find out what professional training they recommend. Your national editorial society will also have guidance. There’s a list of worldwide national editorial societies in the ‘Further reading’ section, too. Practising editors and proofreaders will also have opinions. Ask in online forums about any free course you’re considering, and how it stacks up against paid-for options. Here’s one editor’s opinion: I recommend the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) and the Publishing Training Centre (PTC) for UK editorial training. That recommendation is based on my experience (I’ve not done any free editorial training) but it’s an opinion, not the law! My colleagues will have their own preferences, some of which will be based on where they live.

Pro training courses – what’s on offer

Compare any free course’s syllabus with that of an industry-recognized course. Let’s take a look at the CIEP's proofreading training: Proofreading 1: Introduction (online £103) Time: 10 hours ‘This course is suitable for beginners contemplating a career as a proofreader and for those who need to proofread as part of their job but have had little formal training. [It] teaches the very basics of proofreading; on its own it does not provide the thorough grounding needed to work as a professional proofreader. Apart from introducing the basics of proofreading, the course is designed as a taster to answer the question “Is proofreading for me?”’ You can see the full syllabus here: Proofreading 1: Introduction; it includes:

Proofreading 2: Headway (online £156) Time: 20–25 hours ‘This course is for people who have some knowledge and experience of proofreading and would like to learn more. It […] builds on the basic skills you already have to improve your concentration, focus and judgement.’ You can see the full syllabus here: Proofreading 2: Headway; it includes:

Proofreading 3: Progress (online £156) Time: 20–25 hours ‘This course guides you through more complex general and specialised material, including texts with illustrations, tables, notes and references.’ You can see the full syllabus here: Proofreading 3: Progress; it includes:

This is staged professional industry-recognized training that aims to make you fit for purpose and ready for market. It’s not cheap, nor should it be given that it’ll take a minimum of 50 hours to complete. No one gives away 50 hours of anything for free! If you find a free online proofreading course and it doesn’t include the content covered by the full staged CIEP syllabus outlined above (or an equivalent professional association’s course in your own country), ask yourself whether the material is sufficient for your learning requirements. When free is great – the springboard That’s not to say that freebies aren’t valuable. However, we need to recognize that, usually, what’s on offer is a glimpse, a taster. That taster might well offer insights, knowledge, tips and tools to start us on our journey. Freebies are a springboard. I use them to gauge my fit with what’s on offer. I chose to invest in professional marketing coaching earlier this year. But first I signed up for some free stuff to see whether I liked the hosts and their training methods. I provide my own freebies – my website is packed with them … PDFs, ideas, advice, booklets. These are snippets; people have to pay for my substantive books. Many editors offer free sample edits to give clients a taster; the full editorial service costs. And so it is with editorial training. The PTC offers a free taster programme for its flagship distance-learning proofreading course. The CIEP offers a free proofreading test. Will either make you ready to offer proofreading services to clients in the open market? No. Will they act as signposts for what kinds of issues you need to look out for and whether a proofreading career is for you? Definitely. But you get what you pay for!

Being a professional

Editorial work is no different to accountancy, social work, teaching, graphic design, building, or electrical engineering … you can do it well and to professional standards, or you can do it badly. If you do it well, you’ll be able to give your clients excellent customer service. They’ll use you repeatedly and refer others to you. They’ll give you testimonials that will build your social proof. If you do it badly, you’ll let your clients down. If you’re lucky they’ll only complain and ask for their money back. If you’re not, they’ll tell others how awful your work is – a PR disaster. Any courses that promise miracles for very little to no money and time need to be viewed with caution. Use them to evaluate whether a professional editorial career is right for you. Beyond that, financial investment will be necessary. I hope that helps you, Malika! Further reading

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses. |

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed