|

This free booklet offers one example of how an editor or proofreader might approach testing which pricing model works best for their editing and proofreading business.

I discuss how and why I collect data, and the macro and micro insights I've gained that have helped me to grow my editorial income stream.

Hope you find it useful! Visit the Money Matters page in my resource library to download this free booklet. More resources

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. FIND OUT MORE > Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader > Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn > Learn: Books and courses > Discover: Resources for authors and editors

13 Comments

Apostrophes confound some authors. Not knowing how to use them doesn’t mean you’re a bad writer, but getting them wrong can distract a reader and alter the meaning of what you want to say. This guide shows you how to get it right.

What does an apostrophe look like?

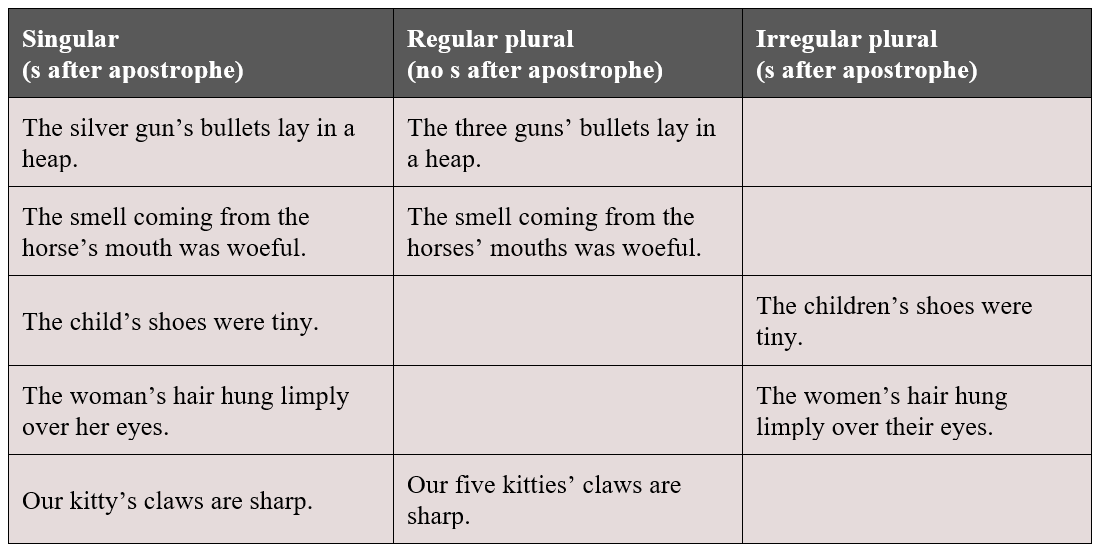

The apostrophe is the same mark as a closing single quotation mark: ’ (unicode 2019). This is worth remembering when you use them in your fiction to indicate the omission of letters at the beginning of a word. More on that further down. What do apostrophes do? Apostrophes have two main jobs: 1. To indicate possession 2. To indicate omission And sometimes a third (though this is rarer and only applies to some expressions): 3. To indicate a plural 1. Indicating possession The English language doesn’t have one set of rules that apply universally. However, when it comes to possessive apostrophes, the following will usually apply: Add an apostrophe after the thing that is doing the possessing.

Possessive apostrophes and names

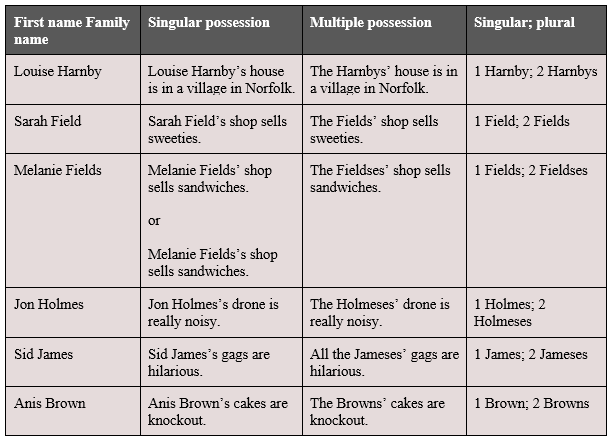

Names can be tricky. The most common problem I see is authors struggling to place the apostrophe correctly when family names are being used in the possessive case, even more so when the name ends with an s. Here are some examples of standard usage to show you how it’s done:

Note that in the Melanie Fields singular-possession example, there are two options. Both are correct but some readers will find the second more difficult to pronounce because there are three s's a row.

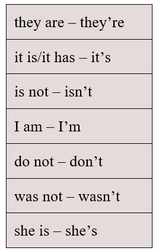

Hart’s Rules (4.2.1 Possession) has this advice: 'An apostrophe and s are generally used with personal names ending in an s, x, or z sound […] but an apostrophe alone may be used in cases where an additional s would cause difficulty in pronunciation, typically after longer names that are not accented on the last or penultimate syllable.’ If you're unsure whether to apply the final s in a case like this, use common sense. Read it aloud to see if you can wrap your tongue around it, and decide whether the meaning is clear. Then choose the version that works best and go for consistency across your file. Pedantry shouldn't trump prescriptivism in effective writing. 2. Indicating omission Indicating omission when one word is created from two In fiction, we often use contracted forms of two words to create a more natural rhythm in the prose, particularly in dialogue. The apostrophes indicate that letters (and spaces) have been removed. Common examples include:

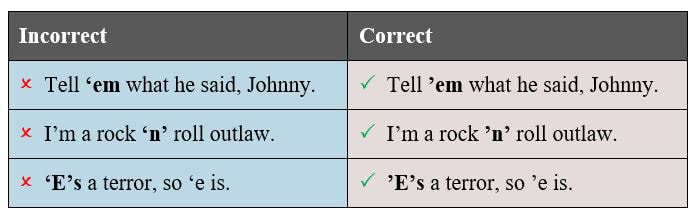

Indicating omission at the beginning, middle and end of single words

We can use an apostrophe to indicate that a letter is missing at the end of a word (dancing – dancin’), the middle of a word (cannot – can’t) and the beginning of a word (horrible – ’orrible). Start-of-word letter omissions are commonly used in fiction writing to indicate informal speech or a speaker’s accent. Make sure you use the correct mark. Microsoft Word automatically inserts an opening single quotation mark (‘) when you type it at the beginning of a word because it assumes you’re using it as a speech indicator. Apostrophes are ALWAYS the closing single quotation mark (’) so do double check if you’re indicating omission at the start of a word.

Indicating omission in numbers and dates

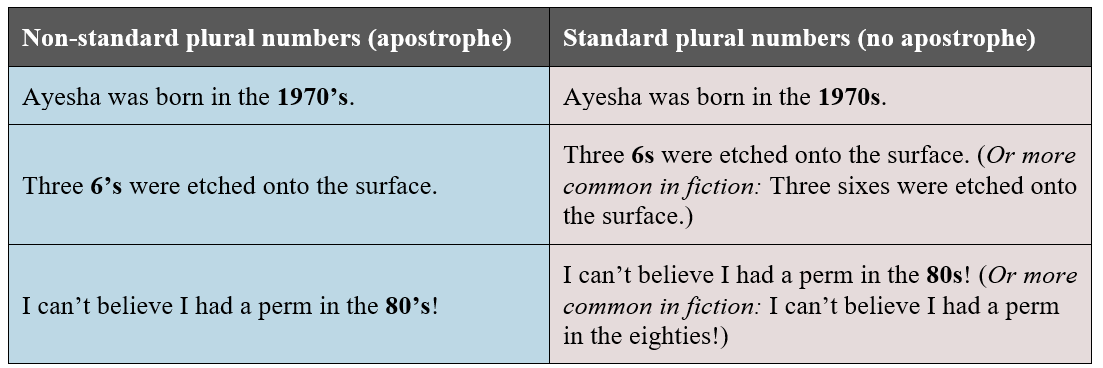

Plural numbers don’t usually require an apostrophe because there’s no ambiguity. In fiction writing, it’s common to spell out numbers for one hundred and below, but even when numerals are used, no apostrophe is needed for plurals.

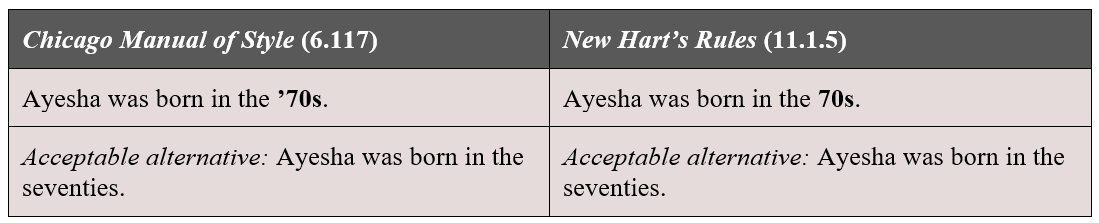

Omission-indicating apostrophes at the beginning of dates are acceptable according to some style manuals. In the example below, the 1970s is abbreviated. It’s conventional in UK writing to follow the NHR example below.

In fiction, however, you can avoid the issue by spelling out the dates. This is universally acceptable, and my preference when writing and editing fiction.

3. Indicating a plural with an apostrophe

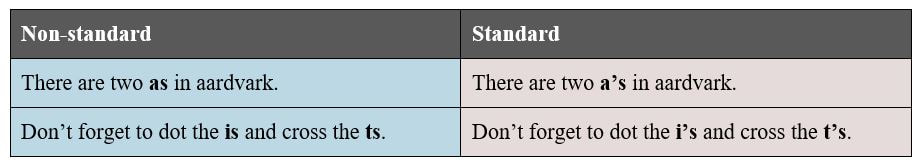

When indicating the plural of lower-case letters – for example, if you want to refer to two instances of the letter a – it’s essential to use an apostrophe because the addition of only an s will lead to confusion. In the non-standard examples below, you can see how the plurals (in bold) form complete words, resulting in ambiguity.

For that reason, it’s considered standard to use an apostrophe (see The Chicago Manual of Style Online 7.15 and New Hart’s Rules 4.2.2).

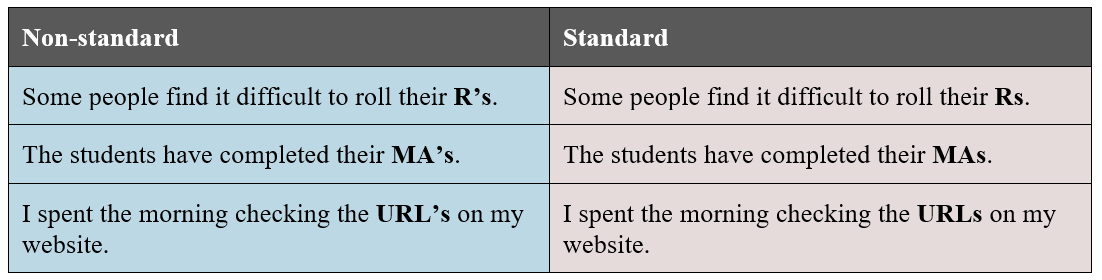

When indicating the plural of upper-case letters, the apostrophe would be considered non-standard because there’s no ambiguity.

Avoiding erroneous apostrophes and possessive pronouns

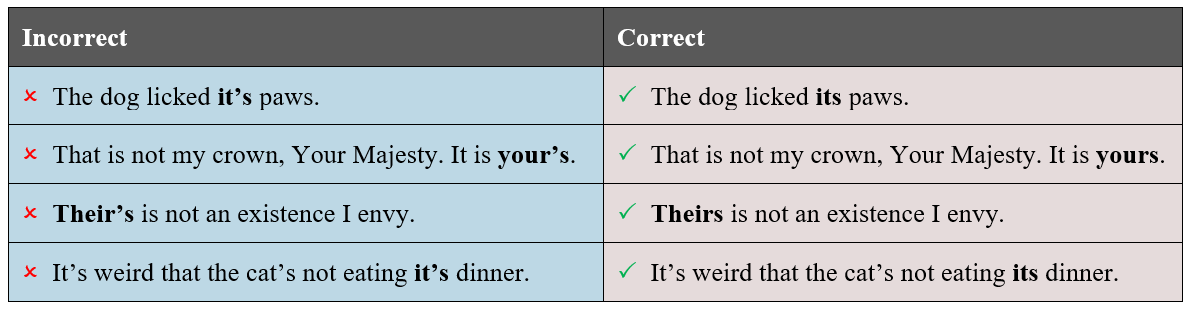

Possessive pronouns are the bane of the apostrophe novice’s writing life, especially its! The following possessive pronouns NEVER need an apostrophe: hers, theirs, yours and its.

If you’re unsure whether to insert an apostrophe in its, say it out loud as it is. If it makes sense, you need an apostrophe; if it doesn’t, you don’t!

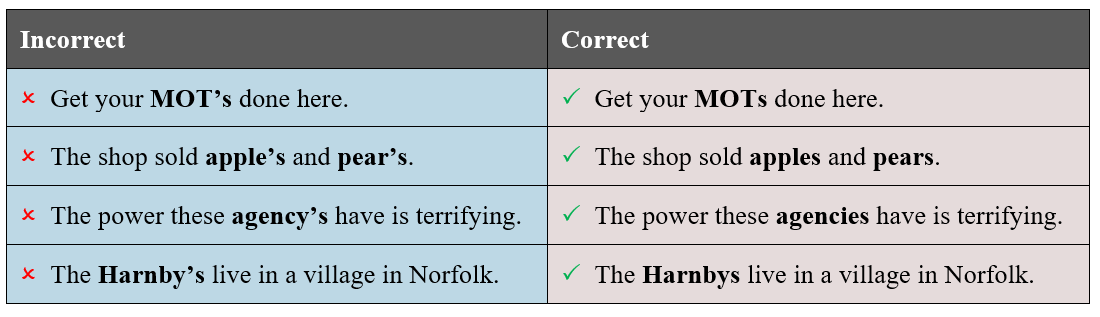

Avoiding erroneous apostrophes in plural forms

The apostrophe novice can fall into the trap of creating plural forms of nouns by adding an apostrophe before the final s.

Summary

I hope you’ve found this overview useful. It isn’t exhaustive – there are entire books about apostrophes. Fucking Apostrophes is one of my favourites. However, when it comes to fiction writing, it’s unlikely that you’ll need to worry about more than the basics covered here. If you’re stuck on where to stick your apostrophe, feel free to ask me for guidance in the comments.

Further reading

Want to revisit this information quickly? Visit the Books and Videos page in my resource library to download this free booklet.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. FIND OUT MORE > Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader > Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn > Learn: Books and courses > Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Does standing up in front of a room full of editors terrify you? I know that feeling. Still, I learned how to love it, which rather took me by surprise. In this post I show you how I did it.

Let’s talk about nerves

I haven’t conquered my nerves about speaking at editing conferences, but that’s okay. Nerves are normal, even for presentations experts like my friend Simon Raybould. More on him later, but for now it’s enough to say that feeling nervous is not the same as suffering from a level of anxiety that renders you unable to step out of your comfort zone and try something that could push your editing business forward. Pushing your business forward Speaking at editing conferences will push your business forward. You’ll get yourself seen and heard. People will understand more about who you are, what you specialize in, and what you stand for (your brand). That will lead to opportunities: work referrals, awareness about courses or books that you offer, discounts on the conference registration price (even payment for some gigs), and invitations to speak at other conferences taking place in cities that require a little more effort to get to. Take me. I live in Norfolk (the UK one). On 7 November, I’ll be speaking at the Society for Editors and Proofreader’s mini-conference in Toronto (register here if you want to join me – it’s now open to non-SfEP members). It’s a massive honour to be invited. I get to talk about my two editorial passions – fiction and marketing! In 2016, I’d probably have shied away from doing this, despite the opportunity to hang out with my favourite Canadians (and a few of my favourite Americans). The words ‘I’m busy’ would have flown from my mouth just in time to curb the nausea. In 2017, I might have agreed to do it as long as I was sharing the spotlight with a pal, though the thought would still have made me queasy. But it’s 2018 and, to my surprise, I’m more than happy to fly solo.

One way to learn to love it

Loathing turned to love because I changed one thing: I dumped the script. This is where I get to talk about Simon again, because he’s the person responsible for making me love speaking at editing conferences. In May 2018, he wrote a blog post for me called 6 tips to help you speak in public with confidence. Tip 4 asks us not to use a script. I was gobsmacked. There was no way in hell I’d dare stand up in front of a group of my peers without having every word of my presentation memorized! We had a long chat about it over Skype, and by the end of that conversation he’d convinced me it was worth testing. And so when the SfEP’s conference director, Beth Hamer, asked me to do a two-hour session, on my own, at the annual conference in Lancaster, I promised her I would. And I promised myself I’d do it without a script. 3 snags with scripts Scripts are inherently problematic. Snag 1: They take time to learn, especially if you’re going to be talking for an hour. Unless you have a brilliant memory. Which I don’t. Snag 2: They’re hard to remember. If they were easy to remember, more of us would be on the stage. Which I’m not. Snag 3: They’re difficult to deliver well. If they were easy to deliver well, more of us would have Oscars and BAFTAs. Which I don’t. No wonder so many of us cringe at the thought of speaking at editing conferences. Even if we manage to learn the damn script, what are the chances that we’ll remember it, given how nervous we are? And if we’re uptight about remembering, what are the chances that we’re going to deliver our script in a way that’s engaging and informative? This is the kind of stuff that’s always been in my head when I think about presenting. All of which can be summed up as follows: at what point will I fail? Going scriptless You can’t fluff a script that doesn’t exist. That in itself gets rid of snags (1) and (2). All you can do is talk about the thing you’ve agreed to talk about. We’re not in the pub or having lunch with our mates, so we still need a structure. I am not a perfect presenter, not by any stretch. But I have embraced an approach that means I will present, and I will enjoy it. This is how I do it:

Because you’re talking rather than delivering a script, you’ll sound more natural. And because you can’t forget any of the key learning points, you’ll feel more relaxed. That’s snag (3) dealt with. There are caveats, of course. You must know your stuff. And you should rehearse. Each rehearsal will be different because you don’t have a script, but you will prove to yourself that you can talk through every one of the key learning points.

Being imperfect – audience expectations

Will you stumble if you’re scriptless? Maybe. Probably. I stumbled several times in Lancaster. But I loved every minute of that workshop. I felt relaxed, and as I talked I was in the moment, not tuned into the next thing I needed to remember. And the delegates gave me some amazing feedback. That they enjoyed it is the most important thing of all. I’m sold on scriptlessness! Plus, having a script doesn’t mean you won’t stumble. You’re human, after all. The difference is that when you’re scriptless, you get to stumble just because you stumbled, not because you forgot anything important or because you were distracted by the pressure of having to remember what’s up next. Here’s something Simon told me during our Skype chat: Your audience will forgive you if you trip up over a word. Your audience will forgive you if you stammer. Your audience will forgive you if you fluff a line and have to restart the sentence and explain something in a different way. Your audience will forgive you for just being an editor rather than a TED Talk speaker. What your audience will not forgive is your failing to deliver the key learning points that you promised you would ... for wasting their time. At the larger editing conferences, delegates have to choose which sessions to attend. So I know that when someone chooses to come to mine, they’re probably missing at least two workshops they’d have learned something valuable from. That I don’t teach them what I promised is unacceptable. And that is the only way I can fail. When will I see you again? If you can get to Toronto on 7 November 2018, please come and listen to me talking about how to build a knockout home page, getting fiction editing work, and marketing an editing business. Will I fluff my words? More than likely. Will I fail? No. I’ve already created slides for my key learning points and rehearsed what I’ll chat about. I might well stumble and stammer, but I will smile at you as I do so, and I will deliver what I've promised!

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. FIND OUT MORE > Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader > Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn > Learn: Books and courses > Discover: Resources for authors and editors

In this article, I offer 12 tips on how to make your book file editor-ready.

Interior book design is something that should be carried out after your book’s been edited, not before.

If you’re creating a printed book, post-design page proofs are perfect for the proofreader because they can check not only your spelling, punctuation and grammar but also the layout. Page proofs are either hard-copy or PDF versions of the book that are laid out exactly as they will appear in the final printed version. You and your proofreader will be looking at what the reader would see if they were to walk into a bookshop, pull the title off the shelf and browse through the pages … almost. The proofreader’s job is to ensure that any final errors and layout problems have been attended to before the book is printed. For a comprehensive overview of what needs to be attended to when proofreading designed page proofs, read this (available free when you sign up to The Editorial Letter): Proofreading checklist: How to check page proofs like a professional.

With copyediting (and proofreading raw-text files for digital books), it’s a different story ...

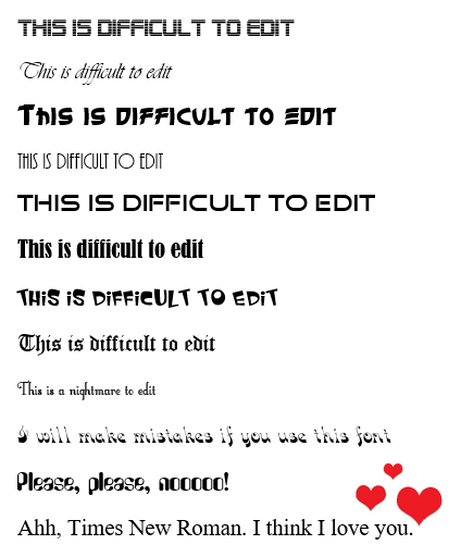

Working with raw-text files If you are asking a professional editor to work on the raw text of your book, follow these 12 recommendations to ensure that the file is editor-friendly. The good news is this: it means less work for you, not more, because you’re not having to design anything … not yet, anyway. 1. File format Most professional fiction editors work in Microsoft Word. That’s because, despite the odd glitch, it’s still the best word-processing software on the planet. It has a range of excellent onboard tools that help your editor style the various elements of your text consistently, and quickly locate potential problems that might need fixing. Word is compatible with a host of macros that complement the editor’s brain and eye. That means they can add an extra level of quality-control to the edit efficiently. Even if you’ve written your book in a different program – for example, Scrivener, Google Docs or Apple Pages – place the text in a Word file before you send it to your editor. You’ll get a better-quality book edit, I promise. 2. Number of files Unless you’ve agreed with your book editor to work serially – i.e. on a chapter-by-chapter basis – create a single master file that contains the full text of your novel. If you send them 75 separate chapters, all they’ll do is combine them into one file … after they’ve finished weeping with frustration. Editors want to ensure that your book is consistent – that Kathyrn doesn’t become Katherine, Catherine or Cathryn. There are Word plug-ins that can help them identify problems like this efficiently but they’re only effective if the editor is working with a single file. The same applies to ensuring that the various elements of your text are formatted consistently. For example, it’s conventional for the first paragraph in a chapter or section to be full-out (not indented). Your editor can use Word’s styles palette to define the appearance of a first paragraph. Once the style has been set, it’s a case of applying it to every relevant paragraph in the file. If they don’t have a master file to work with, they’ll have to create a new style for each one of your 75 chapters or import that style for the same. Fiction editors love master files, and they will love you if that’s what you provide. 3. Fonts You might have decided to use an unconventional font for your book interior. You’re perfectly entitled to use any font you choose ... just spare a thought for your editor’s eyes. When it comes to the editing stage, stick to something like Times New Roman, size 14. It’s a serif font, which means it’s easy on the eye. The less your editor struggles to read the text, the better the quality of their work.

4. Colours

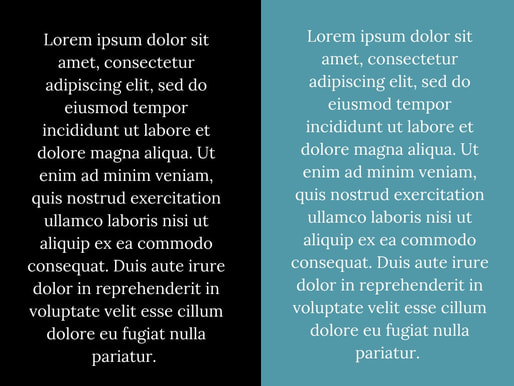

I recommend you use black text on a white page. Again, it’s about readability. The white text on the coloured blocks below certainly stands out, and the contrast is visually appealing, but for editing purposes it’s a challenge.

A couple of years ago, I was asked to copyedit a fabulous book for an indie author. The pages were black, the text pink. The first thing I asked him – no, begged him – was for permission to change the file’s appearance to something more conventional.

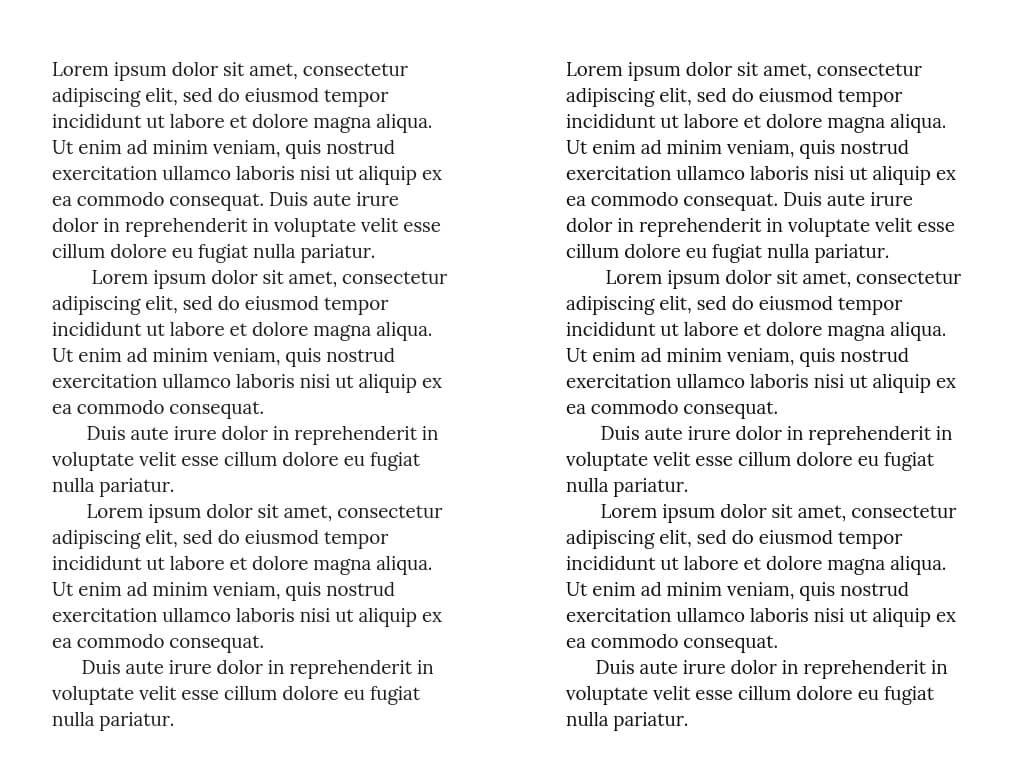

He agreed to save the quirky colourway for the design stage and I was immensely grateful. So was he. I’d have had to increase my price because I would have edited more slowly. 5. Paragraphs Open any novel on your bookshelf and it’s likely you’ll see a text layout something like this:

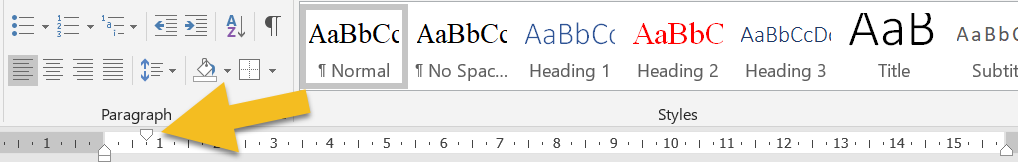

Those indented paragraphs are not made using the tab key. Instead, use Word’s ribbon to create proper indents.

To find out how to create a body-text style with proper indents, watch this video tutorial: Self-editing your fiction in Word: How to use styles.

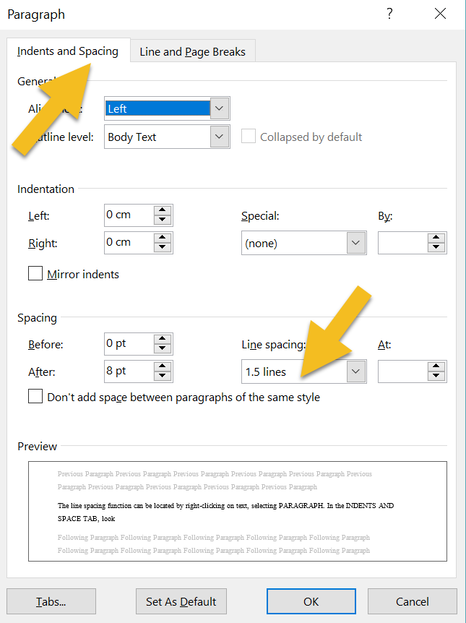

6. Spacing At line and copyediting stage, don’t worry about how many pages your text covers. Instead, give your editor a file with the lines spaced so that the text is easy to read. Setting the line spacing at 1.25 or 1.5 works well for a font size of 12 or 14. The line spacing function can be located by right-clicking on text and selecting PARAGRAPH. A window will open. Make sure you’re in the INDENTS AND SPACING tab. Then amend the LINE SPACING field.

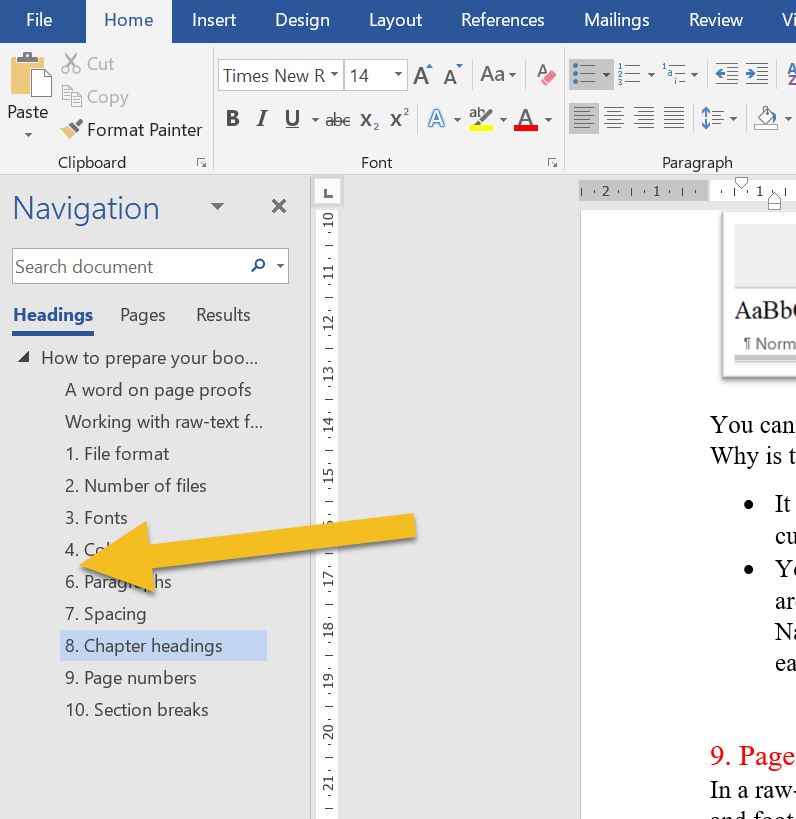

7. Chapter headings

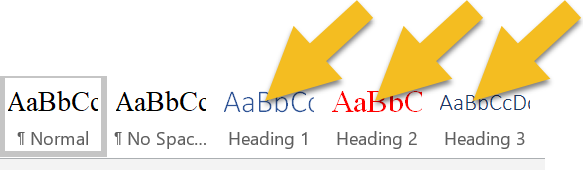

Your editor will adore you if you assign your chapter headings with one of Word’s heading styles:

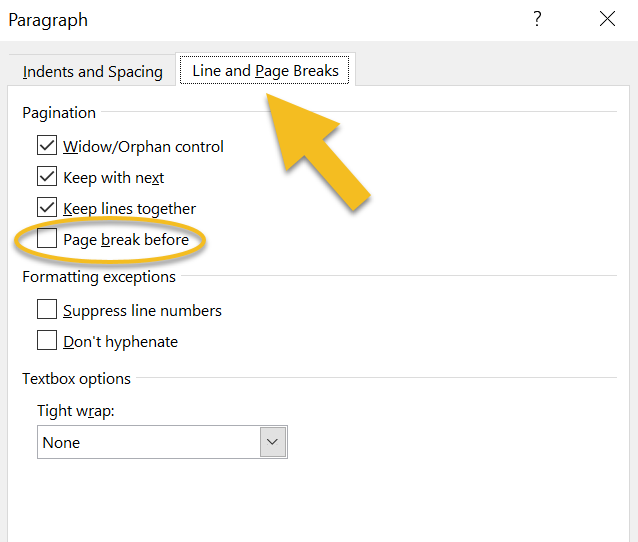

You can even modify the style so that it automatically starts on a fresh page.

Right-click on the heading style, select MODIFY, then FORMAT, then PARAGRAPH. A window will open. Make sure you’re in the LINE AND PAGE BREAKS tab. Check the PAGE BREAK BEFORE box.

Why is this useful?

8. Page numbers

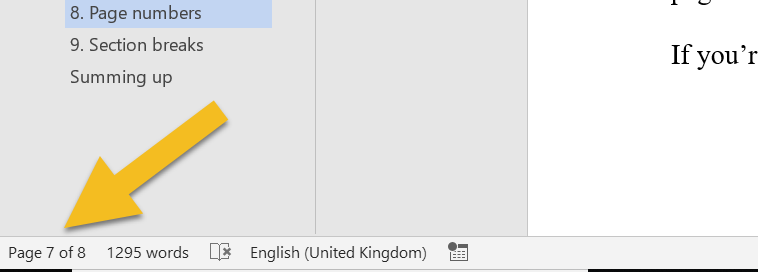

In a raw-text work of fiction, there’s no need for page numbers or other headers and footers. Word records the page number in the bottom-left-hand corner of the screen of a PC, and that’s what an editor will refer to if they need to direct your attention to a specific page.

If you plan to upload a later version of your file for ebook creation, your page numbers will need to be removed anyway.

If you’re printing, save the page numbering for design stage. 9. Section breaks I recommend introducing three asterisks (***) to indicate a section break. You can change them at design stage of course, but they’re handy at editing stage because your editor can see that you intend for there to be a section break. Why not just have a line space? Because sometimes a writer will accidentally hit the return button twice. Your editor will have to spend time working out whether the break is intended rather than focusing on the flow of your text and any errors that need correcting. 10. Pictures/images If your editor needs to check copy against images and their captions, consider placing these in a separate file. Images, especially high-resolution ones, will increase the size of your book file massively, and slow down refreshing when the editor saves. And your editor will save once every few seconds. Sounds bonkers, doesn't it? But the editor who doesn't save regularly is the editor who finds they've lost a precious half-hour's worth of editing because there was a power cut, or a hurricane, or the oven exploded, or whatever. And when they come to email your edited file full of hi-res images, it will be so huge that they'll have to use an external cloud-based transfer service. The file will take an hour to load (unless they have rubbish broadband speed, in which case it will take two or three hours). They'll do the transfer in the evening so that it doesn't slow them down while they're working, meaning their teenage kid will start moaning and giving them that look because Netflix is buffering or Minecraft won't load, or something equally devastating. Save us, I beg you.

On top of all that, amendments, deletions, and additions to the text will cause your carefully placed images to shift into spaces you didn't intend. Better to leave image placement to interior-design stage. It'll save you and your editor time and tears.

11. Manual tables of contents If you've created a table of contents in a Word file prior to copyediting, there's a good chance that a chunk of your page numbers and some of the chapter titles will be wrong by the time your editor has finished. Of course, you can pay them to fix these too. But that could add an extra hour's work onto your bill. Worse, you'll be wasting your money because when the book's interior is designed, everything will change again. I know this because when I proofread for publishers (and that means I'm working on designed page proofs that have been edited multiple times and designed by a professional interior formatter) the table of contents is always messed up. Sort out your table of contents before you do your final design, not at copyediting stage. It'll save you money, I promise. 12. Manual index I'm adding this one in for non-fiction writers, just in case you're reading. If the page numbers against a table of contents get messed up during copyediting, the damage to an index is nothing short of catastrophic. It's not just the page numbers, but the indexed entries too. Spellings might change, so might compound hyphenation. Some key terms will have been removed or changed. Others will have been added. Indexing should come after proofreading, ideally, but certainly not at copyediting stage. Summing up These are just suggestions, not book law, editing law, any kind of law. However, your editor will love you if you make life easier for them, not because they’re lazy but because they want to focus on making your narrative and dialogue sing rather than formatting text so that it’s readable. There’s absolutely a time and a place for great interior design, but pre-editing stage is not it. Save yourself the bother and keep it simple. For more raw-text tidy-up tips, grab this free booklet: Formatting in Word: Find and Replace.

Fancy watching a video instead? Here’s where to find the free tutorial.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. FIND OUT MORE > Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader > Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn > Learn: Books and courses > Discover: Resources for authors and editors

If you're a first-time writer, working out which editorial services you need help with and what you can do yourself can be tricky. Is proofreading enough or do you need additional assistance? A key question is: How does your reader dance?

Here's a free PDF booklet that covers the key issues. In it, you'll find guidance on:

Visit the Books and Videos page in my resource library to download this free booklet.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. FIND OUT MORE > Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader > Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn > Learn: Books and courses > Discover: Resources for authors and editors |

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed