|

Part of my mission with this blog is to help new entrants to the field understand the challenges and benefits of editorial freelancing, and to assist them as they navigate the early stages of their careers. There's no one way to build a business and one's background and preferences will influence the path taken. That's why, from time to time, I like to feature colleagues, particularly those who have a different skill set or career background to mine.

With this in mind, I'm delighted to welcome technical editor Peter Haigh to the Parlour. Peter discusses how he took a strategic approach to developing his editorial business, using his career specialism as a springboard ...

Hello. For those who don’t know me, I’m Peter Haigh and I used to be an electrical power systems engineer. Since November 2015 though, I’ve been a freelance copy-editor and proofreader.

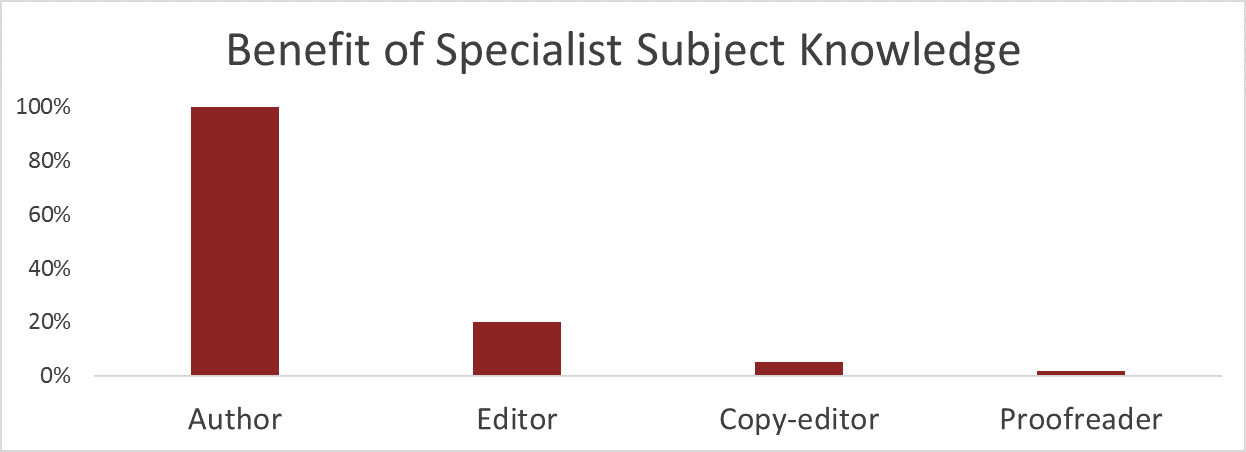

This article is a little bit of a retrospective of how I went from being an engineer to being a proofreader and copy-editor and how I used my specialism to help with this. First, a little background and then I’d like to explore a few truths and myths about 'specialist proofreading' and share my experiences of getting started and then beginning to mature in the world of freelance proofreading/copy-editing. Why the move into proofreading and copy-editing? So, there I was, happily playing with spreadsheets and algorithms (specifying harmonic filter requirements for offshore windfarms) and one day I thought, 'I know, I want to be a proofreader.' Really? No, not really. Then why? It was all part of a deliberate plan to adopt a location-independent lifestyle. I work from apartments near beaches, forests and cities around the world and when I get bored I (along with my companion, Kate of kateproof) simply move somewhere else. That, coupled with the joys of setting my own work hours and leaving corporate quirks behind, was more than enough reason for a complete change of direction. Further details available here. What did I do to get started? Well, I kind of cheated. Having a wife that is now seven years into her freelance career – her empire is now established: an Advanced Professional Member of the SfEP with plenty of queries coming in – was a massive help. The Proofreader's Parlour (thanks, Louise) was also a mine of helpful resources and advice on a breadth of topics, marketing in particular. I did some basic online training and read some books and did their exercises, but I also benefited greatly from having a live-in mentor and trainer. How did it all evolve? The basic flow was: launch a website, do some training, practise on badly written work, build a web presence, do more marketing, develop confidence in my skills, win some good clients, keep them and then look for more! I confess: I still get about 50% of my work in the form of referrals from my wife. The other 50% comes from my website or from an agency that I signed up with last year. How did I market myself as a specialist proofreader/copy-editor? The first steps were made before I left my engineering job. I gathered together all of the business cards I’d collected throughout my career and I connected to as many people as I could on LinkedIn. I told my colleagues about my plans. I hoped that it might lead to work. So far it has led to copy-editing a colleague’s PhD thesis and I continue to edit for a CIGRE working group on a pro bono basis. Maybe one day it’ll pay off, most likely via word of mouth: I left on good terms. How did the client base evolve? To begin with, I sought out power system engineers and power engineering consultancies to scout for work. From this approach, I got one repeat client but on mates’ rates so it paid quite badly. Then, I spanned out via LinkedIn to say hello to various consultancies from all sorts of fields: environmental management, mechanical engineering, pretty much anything where I could connect with someone at a suitable level and very briefly introduce myself and my services. I think it was this that led to me winning what is still one of my best clients: an engineering consultancy, though nothing to do with windfarms or electricity. Another great client I found this way is a financial algorithm developer. How much does the specialism help me? This is something I ask myself sometimes, particularly when clients contact me specifically because of my specialism. With the advantage of hindsight, I sit on the fence a little and say, 'it depends'. When getting started When I set out, I was confident that I could find work in my specialist niche. I guess I did find a little bit of work, but then it’s a highly specialized niche and so naturally the opportunities are limited. I also discovered that large companies have well-defined processes for recruiting freelancers and tend to prefer dealing with large agencies or subcontractors. I remember battling with procurement restrictions from my days of engineering: it doesn’t matter if you are the best proofreader in the world, or how cheap you might be; if you’re not Achilles-registered then you will struggle to work for a utility. (And you don’t even want to know how hard – and expensive – it is to get registered.) To sum it up, I’d say that it helped a little bit. It gave me focus for my marketing, somewhere to start, and in an area where I had a clue about what made the clients tick and what the fancy technical words meant. It felt like I had a USP. Nowadays These days I have ditched my low-paying client from within my niche and continue to look for clients from a far broader range of fields. Most importantly, I have redefined what I think my specialism is. I am no longer a specialist in proofreading/copy-editing power system engineering documents. I’m not even an engineering specialist. I am someone who specializes in improving technical, numerical and scientific documents. Does my specialism help the client? My honest answer: my specialist power systems knowledge does not help them at all. However, at the more general level of being comfortable working with equations, tables, graphs, variables, and other forms of scientific text, I would say that this helps with a wide range of clients. From financial algorithms to social science surveys, knowing your natural log from your base 10 and spotting an unbalanced equation can earn some brownie points at times but, the thing is, that really isn’t proofreading as I know it. I’d say that as you move up the scale towards developmental editing, it becomes more important that you have some appreciation of the subject being worked on. For proofreading it doesn’t help much at all. In fact, here’s a geeky graph to illustrate this:

*Note: I made the numbers up.

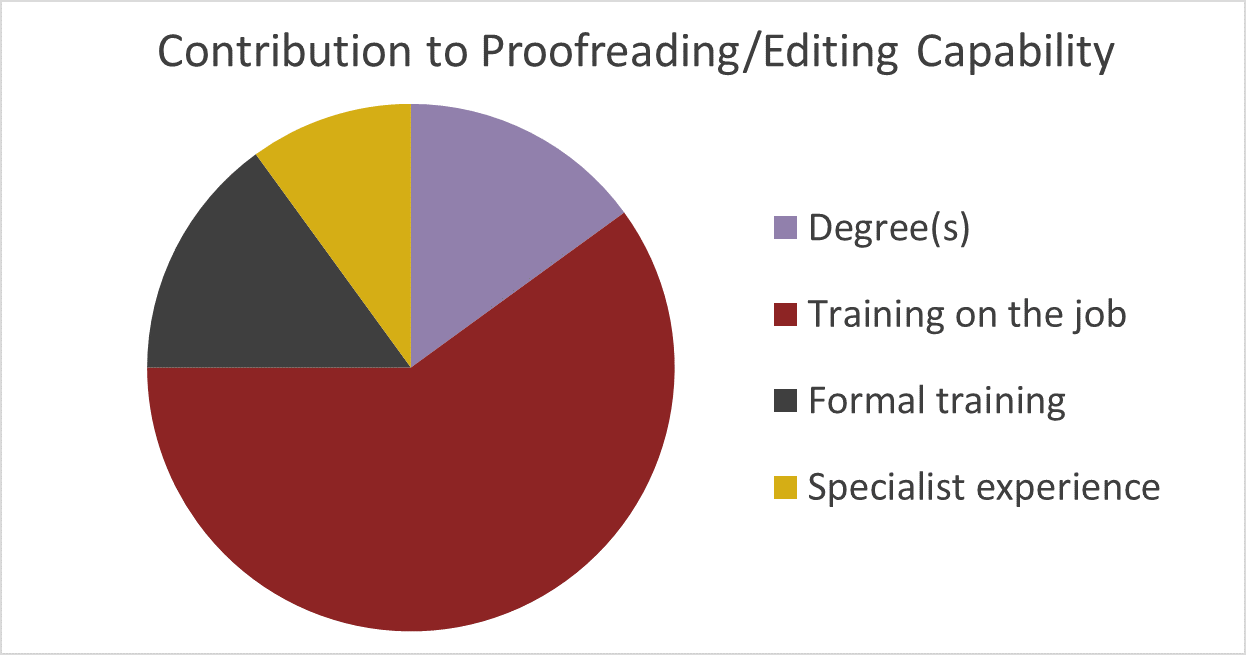

Do qualifications and experience help? I think that at any stage in a career, it is possible to rest on one’s laurels. When starting out, they may be the only support available, so I’d recommend using them as a springboard, along with any specialisms, and growing from there. I certainly set out to build on my specialist experience at first, then sought ways to hone my skills, grow capability and branch out into new fields of experience. Hang on, I can feel a pie chart coming on!

Let’s take a look at each slice of pie.

Degree qualifications I am yet to work on anything related to my philosophy degree (past life) – other than a blog article on the philosophy of proofreading – but it did expose me to lots of books, and I wrote lots of academic essays, dissertations etc. I’d say this helped me a little bit. My engineering degrees exposed me to lots of technical documents, maths and other science stuff, as well as helping my confidence when setting up as a proofreader/editor by giving me a USP. Specialist experience My work experience as an engineer helped expose me to writing, editing and reading lots of technical academic journal papers. This is now something that I edit a lot of, and feel that I am good at, so I guess that helped quite a bit. Formal training I did a basic grammar course (Gpuss), read Barbara Horn’s Copy-editing book and did the exercises and also had access to Kate’s PTC course notes. All of this helped me quite a bit, but was not as helpful as seeing some of Kate’s work (with her clients’ permission, of course) and asking her 'why?' all the time, not to mention Kate checking my first few projects before they were returned to clients. Training on the job My editing and proofreading experience is 60% of the pie for me. Learning on the job was what helped me most and, to begin with, it was a case of working for mates’ rates to get experience. It also helped me to start off by working on, dare I say, badly written documents. The end product would be unrecognizably better, even if some of the finer points were not 100%. Then I kept looking for ways to learn and improve. Editing for an agency helped because, particularly when I first started, their quality control editors reviewed and critiqued my work. This was great because they showed me where I had missed something and made helpful suggestions. They also gave me positive feedback when the quality controllers were happy and now don’t seem to check my work much at all. Summary Hopefully I have given a bit of an insight into what it was like for me transitioning from an engineering specialist to a proofreader/copy-editor and how my specialism has helped me to make that transition. I’ll attempt to leave with some wisdom from my experiences of making the transition:

Peter Haigh is a professional proofreader and copy-editor and a Chartered Engineer. He specializes in improving technical, scientific and numerical documents.

Visit his business website at Technical Editorial or connect on LinkedIn or Facebook.

0 Comments

Developmental editing, line editing, copyediting, proofreading ... what on earth is the difference and what's best for you when self-publishing?

This post featured in Joel Friedlander's Carnival of the Indies #79

A potted guide to the different levels of editing ...

If you’re a beginner writer and you’re planning to self-publish, you’ll be thinking about getting your book fit for market. Some of you might not realize that there are different levels of editing. And even if you do, you might be fuzzy about what distinguishes each service or what it’s usually called. No shame in that, believe me – even among professional publishers and independent editors the terminology differs. Consensus be damned! The irony that this lack of clarity and consistency exists in a profession that prides itself on, well, clarity and consistency isn’t lost on me or my colleagues! In an effort to untangle the issue, I’m offering you a PDF that provides an overview. The basics Think of the editorial process like a play with several acts: writing, drafting, sourcing feedback from beta readers, self-editing, developmental editing or manuscript evaluation, line editing, copyediting, proofreading, publishing. The elements in bold are what we’re focusing on today. In a nutshell Basically, there are two levels of work going on – the macro and the micro.

What terms should you use when sourcing editorial help? There’s a question! My advice is that you explain what you want rather than worrying too much about what it’s called. This is because different editors define their services in different ways. So what should you do?

So, that’s it for now. I hope you’ve found this discussion of the different levels of editing useful. If there are particular questions that you want clarification on, drop me a line and I’ll do my best to answer them. As promised, here’s your guide! Just click on the image to download it to your device.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Here are 8 problems to watch out in your writing. Fix these to raise your game and lift your writing to the next level more quickly. Attending to them at draft stage will reduce your third-party editing costs further down the line.

1. Rushing to publish rather than hushing to polish

Some new authors are so desperate to publish that they omit the drafting stage. Hush time means putting the book aside for a while and revisiting and self-editing with fresh eyes. If you don’t go through the drafting stage, you’re less likely to spot problems with plot, pace, readability and repetition. And that means your book will not be ready for the later stages of editing like copy-editing and proofreading. 2. Overwriting Too much detail Some beginner writers don’t trust their readers to fill in the gaps. This results in writing that gives too much detail. The narrative becomes laboured, boring even. There are some excellent examples in Christina Delay’s 5 Steps to Avoid Overwriting (Jami Gold blog); it’s what Gold calls ‘giving too much stage direction’: Imagine if an author described a character traveling from a store to their home by listing every single action: ‘She inserted the key into the ignition. Turned the key. Waited for the engine to engage. Slipped the engine into reverse. Expertly maneuvered the car out of its parking spot …’ Gold recommends getting straight to the point – unless, of course, something important happens in the detail that’s key to moving the story forward. If it’s just detail that mimics the mundanity of real life, strip it out. Repetition Watch out for repetition, especially ‘wow’ words. If Jo thunders down the hallway, her face like thunder, you have a problem. If the reader is told that Mike is ‘in agony’ and ‘agonized’ several times in one paragraph, trim the fat (and think of some synonyms!). High-intensity scenes of fear, danger, desire or confusion are those most prone to repetition and over-explanation in beginner writing, usually because the author is worried that the reader might not understand what the character’s experiencing. Gold calls these ‘emotionally overwrought passages of purple prose’. When drafting, consider creating a list that features key moments of disclosure and emotion/response. By mapping these moments, you can see whether the descriptions lie in close proximity to each other, and whether you’ve already provided enough detail earlier in the book. Then you can cut accordingly. Less is more. Telling twice Telling twice is another consequence of not trusting the reader to fill in the gaps.

The bold text in the example above simply repeats what we already know and it’s therefore superfluous. It’s another issue to watch out for at self-editing stage. Removing this kind of detail makes the writing leaner and sharper. 3. Logic flop Logic flop happens when writers try to avoid conjunctions (probably because they’ve been told that conjunctions are boring and shouldn’t be overused). This can lead to grammatical hiccups that disfigure the writing and trip up the reader.

In the first example, we have a character seemingly doing two things at once – running through one place while he’s making his way inside another. And to the discerning reader, the first phrase will even seem to modify the second (Roy bolted into the bedroom in a manner of running barefoot along the corridor). The second, edited version introduces a conjunction that brings logic and clarity to the sentence. Conjunctions are a perfectly natural way to join connecting action clauses that happen one after the other, and don’t need to be avoided simply on principle. Don't be afraid to embrace them! 4. Reluctance to use contractions The use of contractions isn’t always appropriate, particularly when the writer wants to introduce formality (e.g. in a historical setting or in academic non-fiction) or emphasis. However, in contemporary novel writing, the narrative can feel laboured if contractions are excluded, especially in dialogue. In real life, people don’t say things like ‘we are going’ and ‘I would have liked to’ so it’s often better to offer the contracted form. If in doubt, say the words out loud. If the likes of ‘we’re going’ and ‘I would’ve liked to’ sound more natural in the context of your book, then use contractions. Readers won’t notice if you do, but they might stumble if you don’t. 5. Overuse of exclamation marks Take care not to overuse exclamation marks. Too many can be distracting and overwhelm the text. Exclamation marks can detract from the gravity of a statement, making it sound upbeat when a different mood was intended – tension, fear, anger, danger. If you’ve used the right words to convey the mood, the exclamation mark will often be superfluous. If you do decide that an exclamation mark is necessary, don’t use more than one. Compare the following:

Read them out loud and decide which one best conveys the speaker’s disbelief. I think the first does the job perfectly well. The second introduces a light-heartedness that may or may not be appropriate. The third is overkill. 6. Speech tagging problems – sighing, smiling, laughing Beginner authors can be reluctant to overuse he said/she said constructions, even though they’re the most discreet way of tagging. Take a look at these examples; the bold versions are clean, effective examples of dialogue tags that won’t trip up the reader.

I'm not saying you should only ever use 'said' – just apply a little caution! 7. Formatting too early Focus on making your book look beautiful after the bulk of the editing has been done. Fancy fonts and heavily designed text are difficult to work with at editing stage. Furthermore, the layout might have to be reworked if there are major additions or deletions to the text during structural editing and copy-editing. Word’s styles palette is sufficient prior to the design stage. You (or your copy-editor) can introduce consistency to the different elements of the book (chapter titles, headings, quoted matter, main text, captions etc.) in a way that’s clear and simple. 8. Unrealistic expectations of what’s possible in one pass Some beginner writers think that one pass – a ‘final proofread’ carried out by a third-party professional – is enough to guarantee absolute perfection. It’s not. The mainstream publishing industry doesn’t believe it’s possible, and nor should the independent author. If you hire a professional to proofread or copy-edit your Word file, and that file has not been through previous rounds of extensive and meticulous editorial revision, there will likely be thousands of amendments:

Don’t expect your editor or proofreader to say, ‘I’ve made 8,000 revisions to your document, compiled 67 queries, spotted four problems with character-history consistency, noticed two character-surname changes, offered 200 suggestions for alternative wording, and I guarantee that, in spite of this, I have not missed one single literal or contextual error.’ Get as many fresh eyes on your work as you can afford. If budget’s an issue, that’s fine, but make sure your expectations reflect this. Good luck with the self-editing process! More resources

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

One of the things new entrants to the field of editorial freelancing want to know is: What’s a good rate? Here's how to work out what's a good or bad fee for the job.

Terms like good, high, fair, low, poor and predatory are problematic because they’re used by individual freelancers to reflect their own experiences and circumstances, which are often very different.

Rate talk can trip us up if we're not careful. And while it can be interesting to listen to colleagues’ opinions of whether a fee is low or high, their views might not be in any way useful for us because we need to make decisions based on our circumstances, not someone else’s.

One of the first potential trip-ups occurs when the conversation takes place between colleagues from different countries. This issue is one of currency, particularly fluctuations in the exchange rate.

Proofreader A lives in Oxnard, CA, USA. She tells her colleagues in an online forum that she’s accepted an offer from an agency to proofread 4,000 words for US$25. The job is budgeted to take one hour. Some of her US colleagues say that the rate is unacceptably low; some even believe that she’s encouraging a race to the bottom by accepting such a fee from an organization whose rates are clearly unfair. Meanwhile, Proofreader B, who lives in Manchester, UK, is reading the forum thread.

Proofreader B needs to earn a minimum of £20 an hour to meet her needs.

Conversations that include blanket terms such as high and low therefore don’t help Proofreader B. Because the exchange rate fluctuates, so do her perceptions of whether a price is good or bad.

It’s not just currency fluctuations that affect our perceptions of good, high, fair, low, poor and predatory in relation to editorial rates. Circumstances muddy the waters too.

Proofreader C lives in Belfast, Northern Ireland. She tells her colleagues in an online forum that she’s accepted an offer from an agency to proofread 4,000 words for £16. The job is budgeted to take one hour. Some of her colleagues say that the rate is unacceptably low; some even believe that she’s encouraging a race to the bottom by accepting such a fee from an organization whose rates are clearly unfair. Meanwhile, Proofreader D, who lives just down the road from C, is reading the forum thread.

Proofreader E lives to the west in Strabane.

Proofreader F lives next door to E.

So, conversations that include blanket terms such as high and low don’t help Proofreaders D, E and F either because although they’re all operating within the same geographical region and the same currency market, their circumstances are all very different. Deciding what rate works for you If you want to work out whether Agency X, Publisher Y or Packager Z’s rates are acceptable, you need to know what good, high, fair, low, poor and predatory mean to you based on your situation – not anyone else’s. The same thing applies to deciding what price to set with clients who come directly to you. Consider the following:

That data – as it applies to you, not your colleagues – will give you a useful initial benchmark with which to evaluate whether a fee is low or high. Your colleagues’ opinions are interesting but your colleagues are not responsible for running your business or your home, so their opinions should not be used to determine whether you accept or decline work at a given price. *** While I don’t believe that colleagues should be the sole determiners of the fees we accept or offer, I do think they’re the go-to people for many, many more types of information. See this post on the value of networking – both online and offline.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Just becoming editors doesn’t bestow special privileges upon us that are not available to other types of working people. Being editors doesn’t mean we’re entitled to be commissioned. Nor does it mean that we’re entitled to earn what we’d like to earn.

Why entitlement won't work for the self-employed

Entitlements are the domain of employees. Freelance editorial pros aren't employees of businesses; they're the owners of those businesses. Work has to be found, which means clients have to be found. We don't live in command economies where the State hands out jobs and you take what you get. We've chosen to run businesses so we have to find a way to make them function successfully. The alternative is unpalatable. In a global market, where clients come from all over, and have different budgets, requirements and expectations, what those clients will be able or prepared to pay will vary enormously. Consequently, of all the clients we find via our extensive marketing efforts, only some will be a price match for us. For that reason, we need to be visible to as many as possible, because the bigger the pot the greater the chance of a conversion. To recap, just being an editor in itself will provide us with neither work nor the money we expect to be paid for the value we believe we bring to the table. Doing visibility is the key to cracking the problem.

Imagine being a teacher ...

Do you know a teacher? Does that person have a paying teaching job? How did they get that teaching job? Are they happy with their salary? If not, ask them what they would have to do to solve the problem. I know a teacher. She trained for the role. After her training was complete, she didn't have a job. So she had to find a job. She didn't sit there and say, ‘I'm a teacher. Where's the work?’ She went and searched for the work. She did loads of research, applied for tons of jobs, reviewed the packages on offer, prepared for a stack of interviews, attended them (which was stressful), filled in her spare time with voluntary work in the education sector to make her CV sing, and finally found a school who wanted her and for whom she wanted to work. For a few years the package worked for her, and then it didn't. She didn't say, ‘This school is predatory.’ She said, ‘I need to find a new job.’ So she did a lot more work. Now that she was more experienced and had higher expectations, it was tricky to find a good match. It took a lot of time, a lot of hard graft, a lot of research, but I never heard her moan. I'd ask how the job search was going. ‘Ticking along. No news yet but I'll know when I find it. The current post isn't perfect but it's better than being unemployed. You hear about Si? He’s been made redundant. Nightmare. He's really down in the dumps.’ My friend did secure a better teaching post. She worked her backside off to find that job. It would've been nice if it had landed in her lap, but that’s not how the teaching sector works. And it's not how the freelance editing sector works either. We have to work our backsides off to find the work we want to do and that pays the fees we want to earn.

Feeling ripped off?

If you're feeling ripped off, that's okay. We’ve all done work that made us feel undervalued and underpaid. That's kind of how my teacher friend was feeling. Time to replace that rip-off work with a better package. Be aware, though – this won't happen overnight. If you're not visible to those offering better-paying work, you'll have to make yourself visible, which takes a lot of hard graft. It took my teacher pal a couple of years to replace her employer with one offering the package she wanted. It might take you a couple of years to make yourself visible to the clients you want to work with. This could mean you have to stick with the current client while you're working your backside off to find a new and better-paying replacement.

The client under the microscope

In the meantime, take a good hard look at the client. If you're feeling ripped off, it can be useful to examine not just the deficiencies but also the benefits. This kind of exercise can shine a light on some of the value you might have overlooked, value that you may not have costed into your analysis. Turnover So the work isn't paying you what you'd like to earn, but is there a lot of it on offer? Every time you receive an email that offers you work on a plate, you get to fill your schedule with absolutely no effort on your part whatsoever. Some people have a few regular clients who provide 90% of their work. Others have a few regular clients who provide only 20% of their work; the other 80% is new business. New business needs to be found and converted into a working relationship. Which leads us to marketing … Marketing If you fill your schedule with a lot of work from one agency (or publisher or packager), and you think said agency is ripping you off, ask yourself how come they've got so much work that they can fill 80% of your schedule and the same percentage of many of your colleagues’ schedules. Is it because they’re marketing their backsides off? Then ask yourself whether you're prepared to make the same investment, because that's what you'll have to do. You'll have to do all the hard graft yourself. Marketing an editorial business isn't just a cute little hobby you dip your toes into a couple of times a year. Well, actually, it can be if you get someone else, like the agency, to do the graft for you (and there’s nothing wrong with that), but there'll be a cost to it because they'll take a cut of every penny you earn. And that's fair enough because there is a cost to finding clients. Marketing takes time, and time is money. So if you don't want to lose a cut, you have to fork out for the marketing investment. In other words, we don't get to have it both ways. We can't expect someone else to find our clients for us and expect to earn as much as if those clients were coming direct. If we did expect that, who'd be ripping off whom?

Still want an exit?

Fair enough. Start actively promoting so that you can phase out the lower-paying client(s) and replace them with new customers who'll pay what you want to earn. Plan for this to take time and a lot of work. If you don't fancy the transitional approach, you can wave goodbye to the work immediately. If that's the case, you either live with someone who can pay all your bills (quite possible, and good for you), you have a trust fund (less likely, but wow), or you're happy to be partially unemployed for a while. As you can probably tell, I favour the transition method! That's because my family situation means my income, although the secondary one in our family, is essential. When I was starting out, I couldn't afford to turn down work on principle while I was finding better-paying alternatives. I had to use a phasing-out approach (if negotiation wasn't on the table). Of course, it may be that you already have enough higher-paying clients to cover the lost income from the existing customer, but if that's the case you probably nailed your marketing strategy years ago!

We're responsible

No one else is responsible for the rates we earn, the clients we find (or whom we enable to find us), the tools we use to make ourselves visible, the equipment we buy, the tax returns we file, the colleagues we talk to, the meetings we attend. It's all down to us. We're not entitled to have anything land in our lap. As business owners, we reap all the benefits, but we have to do all the work. Every time we hand over some of that graft to another entity (finance to the accountant; client-finding to an agency; fee-handling to a money-transfer organisation), we see a cut in profits. That's not being ripped off; it's a cost of business. If you don't want to bear the cost, you have to do it yourself. Being an editor isn't enough when we're freelance. If we're not wearing the many hats required for business ownership (or we resent bearing the cost of someone else wearing them for us), we need to take a step back and consider whether it’s time to make some changes. What we are entitled to What we are entitled to do is to make our own decisions. We’re entitled to choose the clients, the rates, and the types of work that suit our needs. So if you want to work for a packager or an agency that pays less than a colleague thinks is acceptable, but there’s value in it for you and your business, that’s fine. If you want to decline the work and source your own clients direct, that’s fine too. Me? I’ve done both in my time because it was right for me. You’re entitled to the same choice. Good luck!

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses. |

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed