|

Maya has a PhD in social anthropology, and is an experienced editor and proofreader. She’s in the process of expanding her editorial business while continuing to publish academic research. She wants to know how to focus her marketing strategy.

To date, she’s focused on acquiring work through a freelancing website, but the work flow is unpredictable and she’s not convinced it will supply her with a viable income stream in the long term.

She’s created a website but recognizes that it’ll take time to become visible to potential clients, and to earn their trust. She asks: ‘There are a couple of other freelancing websites that look promising, as well as academic editing agencies. Does it make sense to try to sign up to those as well, or is it better to focus on one thing at a time? I'm planning to blog and make YouTube videos about academic writing on top of these things. But is this a case of "less is more" or "more is more"? I’m an experienced editor but completely new to marketing!’ Great questions, Maya. Two things to consider There are two different elements to your strategy here:

Both approaches are important in the editorial industry, so hats off to you for recognizing that even though you’re new to marketing. You’re doing brilliantly! The reason why both approaches are important is because directories and agencies have already done the online visibility work on your behalf. By using them to make your business visible now, you’re freeing up your marketing hours to focus on the longer-burn stuff – your blog and videos. Broadly speaking,

I’ll explain why further down, but first I wanted to ask you whether you’ve considered approaching publishers too. You didn’t mention it in your email so I think it’s worth my taking the time to discuss it here. Publishers and freelance editors – a gift Directories, agencies and content creation are all great ways to acquire clients, albeit over different time frames. The biggest problem the editor faces, however, is getting the client to raise their hand in the first place. ‘I’m interested in you, Maya!’ is what your directory entry, agency listing, blog article or YouTube video needs to make your audience member feel compelled to say. That means working hard to create stand-out information that sets you apart from the competition surrounding you. Furthermore, in the directory and agency fields, there will always be a group of clients looking for cheap rather than brilliant. And in the marketplace more generally, there are potential clients who don’t even realize they need you, or, if they do, which of the different levels of service will be the most appropriate. But here come the publishers! (Sing it, like the Boots ad!) We’re in a rather privileged field of having a core client group who understands exactly what we do, why we’re necessary, and the value we bring to the table. We don’t have to get them to raise their hands; their hands are already in the air! Some publishers will take the time to scour the SfEP’s Directory of Editorial Services, but to my knowledge the single best way to get noticed by a production manager is still to go direct. Email, letter, phone call – whatever you prefer. I worked almost exclusively for publishers for the first half of my freelance career. I had about 10 publisher clients who kept my schedule as full as I needed it to be. Feast and famine? Nope, just feast. Like you, I have a background in the social sciences, so that’s where I focused my initial wave of inquiries. You mentioned in your original email that you’d 'bought my marketing books', so you’ll find more information on how to tackle that in Marketing Your Editing & Proofreading Business. Publishers, like agencies, will give you regular work, and that means you can focus all your marketing juice on creating compelling blog posts and irresistible YouTube vids. Publishers are a bit of a gift like that – while their rates aren’t always top-notch, the time they free up for you by handing you a steady supply of work certainly is. And creating valuable, usable, accessible content does take time. Directories and agencies: more is more Perhaps that’s a bit of an exaggeration! By more is more, I’m not saying you should sign up with 20 directories and agencies; you’ll spend more time being busy creating the entries than you will being productive finding the work! I do think, though, that you needn’t limit oneself to one. If you identify a group of, say, four or five that are used by your core clients to find people like you, I’d recommend you sign up. More is more, as long as you’re selective. There are SEO benefits, too. For certain medium-tail keyword searches, I rank first on page one of Google – but it’s not my website showing up. It’s my SfEP directory entry. And, anyway, you’re in control. You get to accept work, or decline it – whatever suits your needs. The key thing to remember is that if you get too many requests to quote from the directories and agencies, you can always trim and focus on those that deliver the best-quality clients to you. Plus, you’ll never know what’s working if you don’t test in the first place. Testing is something else you’ll see me bang on about in my books, but only because it’s the foundation of any solid marketing strategy. It doesn’t matter if you try something, and that something doesn’t work. You’ll still have learned something, and having learned it you can make an informed decision about what to do next. Otherwise your marketing is just guesswork – which is exhausting at best! So, yes, go ahead. Sign up for a few more and find out what works for you. Evaluate in a few months’ time. Then leave behind the ones that don’t work out and try something else instead. Now let’s deal with the content strategy. Creating delectable content! Less is more (sort of) When I say less is more, I’m talking about platforms, not the actual content itself. This isn’t just me banging my drum. The professionals emphasize this. My own content marketing coaches Andrew and Pete recommend focusing on one or two platforms, and really honing them. Plus, I’m halfway through the online conference Summit on Content Marketing, and speakers Rand Fishkin, Ilise Benun, Dave Jackson, and Stoney deGeyter agree: concentrate on what your core clients are using – in other words, choose the platforms your customers prefer, rather than the ones you prefer. So, you’re planning to use a blog and YouTube to deliver your advice on academic writing. If those are platforms that your core clients like using, then go ahead. And stick to those two – really craft them into something special, something compelling. Some quick tips (you might know the following already but other readers might not, so bear with me!) … Quality Make sure your content is really useful so that it offers solutions for your potential clients. Don’t sell – just solve. I used to call content marketing ‘value-added marketing’ (see the marketing book you’ve bought). Seriously, I didn’t know ‘content’ marketing was a thing until a year ago! I still think it’s an oddly bland name for such an exciting strategy. Anyway, I don’t get to make the rules, so content marketing it is! Focus on value above all else. Value trumps everything (unless your great writing is so blurred as to be unreadable, or the audio quality of your video so poor as to make it unwatchable). If you create a beautiful video, or a blog post with loads of fancy pictures, but the story you’re telling your viewers or readers is of no use to them and doesn’t help them, you won’t grow that audience. But if your video is a little flawed, or your blog post a little ugly, you’ll still grow your audience and build trust and relationships if you’ve made someone’s life easier. It’s no different to friendship. I don’t pick my mates because they look gorgeous – it’s all about the relationship and how we make each other feel. Content marketing’s no different. I’ve tried hard to make my blog look prettier this year. But you know what? Some of my most popular posts are still those I wrote years ago – posts with really long paragraphs of dense narrative – 1,500 words of me telling people what publishers think about proofreading training courses, and another 1,500 of me on how to upload custom stamps of PDF markup symbols. No pictures. No clever SEO titles. Just loads of text. But it’s text that answers the questions that (some) people are asking. Consistency Be consistent with how often you deliver your blogs and videos. The expert view is this: whether you post twice a week, once a week or once a month is less important than choosing one of those and committing to it. That way your readers and viewers get into the routine of engaging with you. Furthermore, if you commit to once a week, but you don’t have enough content to fill that schedule, you’re more likely to feel deflated and stop. Which would be a huge shame! It's better to excite an audience by raising your game than disappointing them by going backwards. Quantity If you write great blogs that are 400 words long, perfect. If you need 2,000 words, perfect. If your videos need to be 5 minutes long to solve your client’s problems, make them 5 minutes long. If they need to be longer, and that’s what your audience wants, make them longer. Just make sure that every word and every minute is full of value. I know I’m a right old rambler so I struggle to make every word count. Let’s just call me chatty! Delivery Think about how you’ll direct people to your blog and YT channel. I post to Facebook Twitter and LinkedIn to make editors and writers aware of what’s new on my blog. I’ve also recently created a mailing list for writers to enable me to alert them when new self-publishing resources are available. And, these days, Google Search is working wonders for me. In time, it’ll work for you to if you commit to creating all that delicious stuff for your potential clients! If academic writers are also using Twitter, FB and LI to get their updates, those are the channels you should use to direct them to your blog and video platforms. If they’re using some other channel to get their news, that’s where you should be. Again, it’s about what your listeners and readers want, rather than your own preferences Hope that’s helped, Maya. Thanks so much for asking two great questions.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

0 Comments

In this Q&A, I look at how to set up a proofreading business, how to acquire clients and how to handle payments.

One of the blog's readers, Charlie, got in touch with several questions:

Phew! That’s a lot of questions so I’ll only be able to scratch the surface, but I’m confident I can point you in the right direction, Charlie. First things – going deeper Here are four resources that dig deeper into all your queries , though you’ll have to cough up a few quid for them!

They’ll tell you pretty much everything you need to know about starting out and keeping going. Might I also suggest you join the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), the UK’s national editorial society? The forums provide a warm and supportive environment for old hands and newbies alike. How will clients pay me? A better question might be how would you like to be paid? For example, I accept cheques (reluctantly!), PayPal (convenient for international clients), and direct bank transfer (easy-peasy). Other options include Stripe, TransferWise and CurrencyFair. I send an invoice as soon as a project’s complete, but some of my colleagues prefer to do all their invoicing for the month in one fell swoop. It’s a matter of personal choice and what works for each business owner in terms of efficiency. You can download an invoice template from my Other Resources page. How do I register with HMRC and what do I need to tell them? Quite honestly, the easiest way to deal with HMRC is to give them a call. I found them incredibly helpful when I first started my editorial business. Believe me, they’ll put your mind at rest. Sue’s book (mentioned above) has lots of information about dealing with HMRC. My primary piece of advice is to keep a record of what you spend and what you earn in relation to your business. There’s an accounting template on the Editor Resources page that shows you what I record for each project. How do I keep track of the hours I spend working? I record my hours in the accounting template. That way, everything’s in one place. I keep track of time the old-fashioned way – with a pen and a piece of paper! Other colleagues use various time-tracking tools and widgets, e.g. Toggl. Keeping track of how much time you spend on a project is important for gauging how efficient you are. Bear in mind, though, that not all clients will be prepared to pay you for the hours you work. Rather, they’ll pay you for the hours they think the job should take you. This is often the case with publishers and packagers. When you’re in control of the setting the price of a project (e.g. with independent writers, students, businesses etc.), you’ll need to assess how long the project will take and how much you want to earn from it. This comes with experience; it’s likely you won’t hit the mark in the start-up phase of your proofreading business. Don’t fret about this, though. You’ll get better at estimating over time. And by tracking how long each project takes to complete, and what you earned, you’ll get a sense of what’s possible in an hour or per 1,000 words. How much should I charge? Take a look at the following articles here on The Editing Blog:

What you charge will be determined by your particular needs, your ability to access clients who’ll meet those needs, whom you’re working for, and what you’re doing. If you work for publishers and packagers, they’ll control the price – you’ll be a price-accepter. If you work for businesses, independent authors, academics, and students, you’ll offer a price in the hope that they’ll accept – you’ll be a price-setter. If the second option sounds a better financial option, bear in mind that, even if it is, it’s harder work! Publishers and packagers do all the client-acquisition work on your behalf, while acquiring clients for whom you’re a price setter means you need to actively promote your business on a regular basis so that you’re interesting and discoverable to clients across the platforms they’re using to find people like us (e.g. Google). How do I acquire assignments? My line on this is: when you set up your own business you’ll have two jobs:

I’ve shared all my experience of editorial business promotion in these resources:

What I’ll say here is that there’s no single way to go about it, not least because different client types use different platforms to find their proofreaders and editors.

For example, content marketing is not the most efficient way to go about acquiring publisher clients – honestly, just get on the phone or write a letter/email instead. If you want to work for independent authors, though, it’s one of the most powerful methods of being discoverable. Conversely, phone calls to publishers will reap results (if you make enough of them), but for indie authors this method will take you into Ghostbusters territory – who you gonna call?! My advice is to put yourself in your customer’s shoes and ask:

Can I use my prior career experience? Absolutely – it will be one of your unique selling points. For example, I’d worked for a social science publisher for many years prior to starting my business, This, along with my politics degree, helped to make me an interesting prospect for social science publishers with politics lists. Wordsmith Janet MacMillan is a former lawyer – now her client base includes legal publishers, legal students, academics and law firms. Both of us understand the language our respective disciplines, and that means we’re more likely to spot errors in related texts than someone with, say, a nursing background. My advice to new starters is: always specialize first in what you know. Later, if you wish, you can diversify, or transition to another specialism (I’m now a fiction copyeditor and proofreader). So, in the start-up phase, use your career experience to help you determine which core clients you’re going to target. Then think about how you'll communicate with them in a way that makes them want to consider you as their proofreader. Here are two resources to help you think about how to create a stand-out brand identity using a client-centric approach:

Do you accept volunteers or offer apprenticeships? I don’t, Charlie – sorry. I’m a one-woman show. That’s critical to my business model. My clients hire me and only me to work on their books. That doesn’t mean that mentoring programs aren’t a superb option. Time to think about training! I’d strongly recommend you do some professional proofreading training to prepare yourself for market. It’ll show you where your strengths are, and help you fix your weaknesses. Training has three core benefits:

TheChartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) and The Publishing Training Centre are my recommendations … purely because I have personal experience of their courses on which to base an opinion. There are other options available, though. The CIEP runs a mentoring programme, too, though you must have completed some initial training beforehand. Last things That’s it, Charlie – a whirlwind tour of how to set up a proofreading business! I hope you find the guidance useful. I realize there’s a lot to think about. If you decide to join the club, you’ll find a supportive community awaiting you, one that stretches well beyond the geographical boundaries of the UK. Good luck!

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses. How to make a living from self-publishing fiction This week's post is a cracker. Self-published author Jeff Carson has kindly agreed to discuss his writing journey.

This post featured in Joel Friedlander's Carnival of the Indies #81

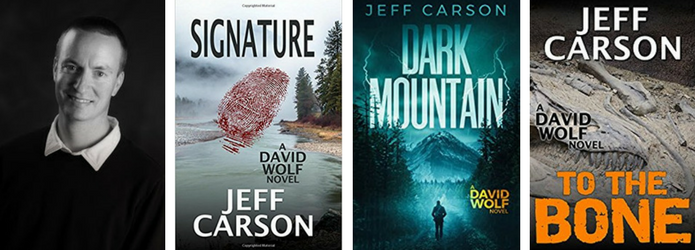

Jeff's a mystery and thriller writer from Colorado. Writing is his full-time job and he makes a living from his self-published series.

That's a dream for millions of independent authors; below, Jeff shares 11 tips on how he turned that dream into a reality. If you're at the start of your self-publishing adventure, this is definitely for you!

My name is Jeff Carson and I’m the author of a series starring David Wolf, a cop living in the fictional town of Rocky Points in the Colorado Rockies. Right now, I’ve written ten books in the series.

When I first started out writing, I remember being tormented at night by questions swimming in my head (and by mosquitos … at the time, we were in Italy for a year, and they were thick that summer, I tell you). Questions like: Can I really do this? Can I make a living at it? Is this just a waste of my time? What if everyone hates the books?

By finding a few people online who’d made a success of becoming a self-published author, I was able to get a lot of my questions answered and some inspiration that propelled me towards making a living as a fiction writer. I despise playing the guru, and I’m cringing a little as I write this, but I have accomplished the goals I laid out five years ago. So I have to say that I feel l’ve succeeded in the self-publishing realm. There are others, many others, who would scoff at my level of accomplishment, but this blog post isn’t for them. This is for those who are in the position I once was, in that sweat-soaked Italian bed. Here are 11 things that have helped me succeed as a self-published author. 1. I want to make a living doing this That’s been the over-arching goal from the beginning. I wanted my paycheck to come from writing. I wanted to make money twenty-four hours per day from people reading my books. I’ve met many people who approach writing as a therapeutic tool for their lives. That’s fine. But 100% of people who write get the therapeutic benefit. One only makes money from it if it’s a goal. You don't wake up with a horse one day by random accident. There’s a lot of intention and action that goes into suddenly having a hay-eating animal roaming around in the back yard. Same thing goes with earning a living from writing. 2. I wrote a book series I learned that if you want to make money from writing fiction, the odds of success go up dramatically by writing a series. Since my goal was to make money with this gig, naturally I wrote a series. Harlan Coben is the exception, not the norm. On this note, I learned the hard way to not leave books ending on a cliff-hanger. I'd done this with book one and received a lot of negative reviews. I’ve since fixed the novel so that all story goals are resolved and it ends completely. In my series, my characters grow and their lives change from each book to the next, but I try to make each book a stand-alone. This helps with marketing, too, since anyone can pick up one of the David Wolf novels at any point in the series and feel grounded and up to speed. 3. I over-estimated, or realistically estimated, the level of work it would take to achieve my goal (of making a living writing) I knew that one book in a series, the first book I’d ever written and published in my entire life, would make no money. Pessimistic? It’s not. First, I was learning how to write a story. Second, I wasn’t expecting to gain a wide audience with a single book taking up a single slot in the vast Amazon universe. I knew book one was the hook – the mouth of a funnel – that would lead to the rest of the books in the series. In fact, I knew I was probably going to offer the first book for free. I needed multiple books in multiple categories grabbing people’s attention, all of them leading readers to the other books sitting in other categories. The series would act as a big net. I figured that after three books I’d be making some ‘extra money’. I hoped that after five I’d be making enough money to quit all other work and concentrate on writing only. Then I doubled that number. Therefore, I created a goal of writing ten books; then I’d judge the venture one way or another. In reality, after five books I was able to write full-time and make a full-time living wage. Now that I’m on book eleven, my goals, expectations, and earnings have elevated.

At the beginning, I felt that if I set my work expectations too low, I’d become discouraged, and fast. Because if after, say, four books I was still irrelevant and making nothing, then my hopes would be dashed.

Some people would call a ten-book ‘realistic expectation’ pessimistic, but in my mind it’s the reason I kept going when, after three books, I’d known months that wouldn’t have paid for a week’s worth of groceries. 4. I concentrate on what I want every day I’ve filled two college-ruled notebooks with lists of my goals. Every day (or most days) I open up a notebook, list the writing goals/life goals with specific deadlines, such as when I’ll finish the first draft and when I’ll publish, and then I get to work. I learned this technique by reading this Brian Tracy book on goal-setting: Goals! How to Get Everything You Want – Faster Than You Ever Thought Possible. That book definitely changed my life. I'd never even had goals before reading that book. Now I always set goals. Deadlines always get pushed back, which would be depressing if I let myself to think about it. But the system doesn’t allow for that. Each day is a new sheet, and a new list of goals with either the same deadlines or adjusted deadlines. Looking back on previous lists of goals is not permitted. 5. I read the bad reviews This is a biggie. I’ve heard some authors say, ‘I just ignore the bad reviews.’ I adopted that stance for quite a while, actually. But there’s always something to learn from a bad review. In fact, I think it’s dangerous and irresponsible if you ignore the one- and two-star shellacking some people take pride in giving out between hangover-induced trips to the bathroom, the sons of bitches. Some people get specific – ‘Nice try. A Sig Sauer P226 doesn’t have a safety! Amateur writer at best. I will not be reading another piece of filth by this author.’ So, fine. You skim past the amateur comment and go fix the book so that the special agent DOESN’T flick off the safety as she steps out of her SUV. I think my books are orders of magnitude better because of the bad reviews. I figure that if somebody came up to me on the street, pointed, laughed, and criticized my outfit, I’d shake my head and move on, not in the least worried about that person a few steps later. But if her criticism is, ‘Your fly’s down … oh, yeah, and your pants are on backwards. Idiot,’ well, then, I want to know that. 6. Screw it. I don’t need social media Early on, I adopted the stance that I needed to write my way into relevance as a writer, not tweet, post, or whatever my way into it. Once I adopted this mindset, a weight lifted off my back. I hated it for some reason. I couldn’t get a grasp on social media, so I just let go of it. My investigation leading up to my decision showed a correlation between how much an author published books and how successful they were, between how many positive reviews a book had and how successful it was. I could check an author’s success by looking at the rankings of their books on Amazon and other market places. There was no correlation, however, between how present people were on social media and their book rankings. In fact, more often than not, I saw that people who were successful had all but abandoned their social media accounts. In contrast, there were people all over Twitter and Facebook, with hundreds of thousands of friends/followers, and books lost in obscurity. Clearly there are exceptions, and some people have great success with social media, but my reasoning was: you write your way into being a writer. I rarely post on Facebook, and when I do, it’s usually a link to my new books – classic poor social media behavior. Screw it. I don’t care.

7. I am accessible

I respond to every communication sent to me. I think this is huge as a writer, or as a person in general. Nothing irks me more than somebody simply not responding to something. The most surprising thing about writing, and that I sometimes get all teary-eyed about, is the amount of love people will send your way after they’ve read your novel. People will click on the email address (which I put in the back of the book) and contact me, telling me how much they like my book. For me to not say thanks is plain psycho. Plus, it’s just good business. People who like you are more likely to share the news about your work. 8. I have a newsletter email list This is one of those things I heard people preaching – you have to have an email list of readers – but never did anything about. It took me four freaking books to finally put my email list in place. But I finally did, and that’s when I was finally able to write full time. It only took two days to write and publish a short story, which I give away on my blog as a thank-you if somebody signs up for the new-release newsletter. Now, when I have a new release, I launch the book to thousands of people, versus dropping it into a field of crickets. 9. I write in sprints first, edit later This is one of those huge game-changers for me. I was getting upset sitting in front of the computer every day but only coming out with one or two thousand words. Now, I write in sprints, which means I write in thirty-minute blocks, take a five-minute break, and then do it again. Using the backspace button is not allowed (a rule I break all the time … my OCD won’t allow David Wolf’s name to be Wols for more than a few seconds). It took me six or so books to employ the sprint tactic, and now I’ll never write any other way. 10. I have a self-editing PLAN After tapping out a real crappy draft of a terrible book, then going back through a few times, editing, ironing out inconsistencies, tightening up descriptions of dead bodies, etc., I have in the past simply read and re-read the book, then tweaked until I felt it was ‘as good as I can get it’. I’m ashamed to say, it’s only been recently that I’ve implemented a self-editing plan. The plan is something like …

11. I hire an editor who does it for a living, for a rate that allows her to do it for a living After seven books, going through three editors, and becoming frustrated with the service I was getting, I realized that I needed to hire an editor who was an editor and only an editor, and who charged a rate that clearly allowed her to feel properly compensated. The alternative is hiring somebody who does the work on the side for cheap. They’re pressed for time. They’re secretly (I imagine, because I would be) pissed off about being underpaid for a job that deserves more money. The equation adds up to a poor editing job on the finished product … suspicious stretches of pages – five, ten at a time – without a single mark on them. The saying goes, ‘You get what you pay for,’ and it can get tricky when paying for editing services. For years, I tried to get away with paying less. And I definitely got less. ... In today’s publishing environment, I know that, for me, every bit of advice helps. I hope at least one of the tips above helps you on your journey to becoming a successful self-published writer.

Where to find Jeff and his books

Louise Harnby is a fiction copyeditor and proofreader. She curates The Proofreader's Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. If you're an author, you might like to visit Louise’s Writing Library to access my latest self-publishing resources, all of which are free and available instantly.

If you’re at the beginning stages of your writing career, you’ll still be navigating your way through the world of publishing. And you probably have a ton of questions. One of those will likely be: What kind of editor do I need to help me get my book ready? The natural follow-up to that is: How do I find that person?

I offered guidance on what kind of editor to hire and when in ‘The different levels of editing. Proofreading and beyond’. Today, I’m focusing on how you should source that person.

So as not to muddy the waters, I’m assuming you’ve already decided what kind of help you want: developmental, copy/line editing or final prepublication proofreading. If you’re still not sure, I’ve included a PDF that summarizes the different levels of editing at the bottom of this article. Now let’s look at how to find the right person. My recommendations fall into two categories:

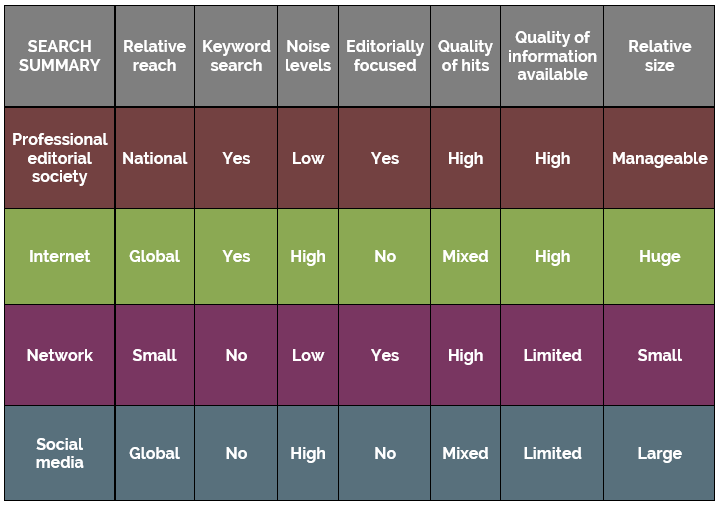

Search (1): Professional associations

Your national editorial society is a great place to start, for four reasons:

Being able to target your search means higher-quality results for less of your valuable time. Woo hoo! The UK’s professional editorial association is the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) and there’s a global list here: Professional societies and associations. A limitation of national professional editorial societies is that they’re national. There’s absolutely no reason why you should source editorial help from someone in your own backyard. Many editorial pros work with clients from all over the world. Search (2): The internet The internet is the biggest and most amazing directory on the planet so it’s a brilliant place to search. Your perfect-fit editorial pro is out there, just waiting for you to touch base. There’s a problem, though: the internet is the biggest and most amazing directory on the planet so it’s a terrible place to search. Your perfect-fit editorial pro is buried, waiting for you to dig her out. Go too broad with your keywords and you might miss her. Go too narrow and … yep, you might miss her. Of course, you might find her, too. As Google sometimes prompts us: are you feeling lucky? And there’s something else to bear in mind – and I say this as someone with page-one Google rankings for the term ‘proofreader’, so it’s not a case of sour grapes – being high up in Google doesn’t mean the proofreader or editor is necessarily the best fit for you; it means they’re an effective marketer. And, conversely, just because someone’s website is ranked highly for niche long-tail keyword searches doesn’t mean that another person who didn’t pepper their website with those particular terms isn’t worth considering, too. That means you need to do a lot of Google legwork to find the best fit and to get a really good batch of potential people to work with. I’m not saying don’t use the internet. Its global nature is an appealing feature, one that the national editorial societies can’t compete with. I’m saying recognize its limitations. It’s amazing but it’s crowded, so you’ll need to invest some time to make it work for you. And that’s why I’ve given professional associations the number-one slot in this list of search options. Search (3): Your network If you’ve developed a solid network of fellow writers, that could be a super resource from which to get recommendations. Bear in mind, however, that the best fit for your writer pal is not necessarily the best fit for you. It’s a small resource given the size of the decision. You might be writing in a different genre, or you might need help with a different level of editing. Some professional editors specialize in one or two levels (e.g. proofreading and copyediting; or developmental editing and manuscript evaluation). Others offer all of the levels but still feel most comfortable in one or two. So tap your network for advice, but back it up with other searches. Search (4): Social media Social media platforms can be useful. They’re global but they have their limitations:

Again, back up with other searches. Here's a summary of the tools you might use to search for an editor or proofreader:

Now let’s take a look at how you might refine your initial searches.

You’ve found 37 developmental editors or copyeditors or proofreaders … whatever you need. All of them look great – they all have experience; can spell properly; are well educated and professional; and have a keen eye for detail and the appropriate training and qualifications. How are you going to narrow that down to something manageable? Refine (1): Genre experience One way is to look at their portfolios, which tell you whether they’re used to working with books in your genre.

A portfolio does not an editor make, and it shouldn’t be the sole determiner of whom you choose by any means. It will, though, give you a feel for who’s used to working with writing like yours. Refine (2): Best versus best fit – samples Best versus best fit is worth considering when it comes to choosing third-party editorial help. At proofreading stage, you need precision; it’s all about quality control. At the earlier stages of editing (e.g. copy/line) emotional engagement will come into play. It’s therefore a good idea to ask for a sample (either free or paid for). A sample will allow you to see who ‘gets’ your writing. Sentence-level tweaking is subjective to a degree (when it comes to suggesting minor recasts, for example) and it may be that five editors all spot the same typos and grammar errors but handle the wordiness rather differently. It’s not about right or wrong, but rather about responsiveness. Refine (3): Endorsements A third narrowing-down technique is to look at what other writers say about a proofreader or editor. Take a look at their testimonials. Have other writers been prepared to publicly endorse the editorial pro? Have mainstream publishers stuck their necks out and praised the work? Testimonials aren’t a foolproof way of determining excellence; like portfolios, they give you a glimpse of what the editors have done, whom they’ve worked with and the impressions they’ve made. They’re just one way of evaluating what’s on offer. So that’s it – a potted guide to finding a proofreader, copyeditor or developmental editor. I wish you luck with your search and with your writing journey! Here’s the information on the different levels of editing I promised. Just click on the image to download.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with independent authors of commercial fiction, particularly crime, thriller and mystery writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses. How do mainstream publishers produce books? And should you mimic them? Help for self-publishers15/5/2017

Unsure how mainstream publishers manage the editorial process? This post provides an overview and shows you why books take so long to get to market and what some of the costs are (to the publisher and even to the author!).

A note on scheduling … and marketing

In the mainstream publishing industry, books are commissioned and scheduled for publication often up to a year and a half in advance, sometimes longer! That time frame isn’t down to the publisher being busy with other stuff; rather, it’s about giving the relevant team members the necessary time to take the book through a rigorous editing process and carry out a staged prepublication marketing campaign. TOP TIP: When self-publishing, instead of promoting your book at the eleventh hour, plan and implement your marketing campaign well ahead of launch. That way, you can create a fan base and generate excitement about your novel before it goes to market, even pulling in some pre-order sales. How do mainstream publishers produce books? Every press’s editorial production chain is slightly different but the broad principles apply.

3. Design #1 When the key members have agreed that the correction stage is complete, the raw-text files are handed over to a typesetter (if the book is to be printed). This is where the first proofs are created. The typesetter formats the book so that the layout conforms to the agreed house style and is designed so that maximum use of the page space is made. Printing is very expensive so minimizing wasted white space is a key factor in the process. The typesetter needs to balance costs against aesthetics.

This is the FIRST PROOF stage. The first proofs are essentially a first draft of what the finished product will look like when it’s picked off the shelves in a bookshop. The completed first proofs are delivered back to the production manager.

KEY MEMBERS: Author, production manager, typesetter 4. Proofreading The production manager sends the first proofs (perhaps a chunk of paper but increasingly a PDF) to the author and the proofreader (usually a freelancer). Both will check them carefully. The proofreader may be asked to proofread blind or against the original raw-text files worked on by the copyeditor (the latter is much slower). The proofreader’s job is not to make extensive changes, but rather to draw attention to any final spelling, punctuation, grammar, consistency or logic problems missed at earlier rounds of editing or introduced during the typesetting stage. Every change the proofreader makes or suggests needs to be handled carefully in case it has a knock-on effect on the design, the page count and, consequently, the printing costs. It’s demanding work that requires experience and judgement about when to change and when to leave well enough alone. Some publishers even pass some of these costs back to the author – eek!

This is the QUALITY CONTROL or CHECKING stage. The proofreader does not amend the raw text but annotates the paper or digital pages, often using proof-correction markup language (a kind of shorthand that looks like hieroglyphics to the untrained eye!).

KEY MEMBERS: Author, production manager, proofreader, typesetter 5. Final revision: Design #2 Now the proofreader’s corrected file and the author’s version go back to the production manager, who has to collate all the final amendments and instruct the typesetter to make the necessary corrections. The typesetter creates a revised file and returns it to the production manager for sign-off.

This the SECOND PROOF stage. We’re nearly there!

KEY MEMBERS: Author, production manager, typesetter 6. File creation and distribution (print, digital or both) The final countdown! The production manager works with the typesetter and printer to create the final print book that will be delivered to the relevant distribution channels. In the case of e-books, the production manager will commission a digital formatter to create e-Pub files that are compatible with the market’s major e-readers and other digital devices.

This is the PUBLISHING stage. The book is delivered to market!

KEY MEMBERS: Production manager, digital formatter, typesetter, printer The elusive publishing deal and the editorial process As you can see, there are a lot of stages and a lot of people involved. And that’s why it takes so long and why it’s so expensive to publish. It also explains, in part, why writers can find it so hard to get a mainstream publishing deal; if the book bombs, there’s no return on all that investment. For publishers, novels that need a lot of work, or that don’t fit neatly into an obvious and currently popular genre, are difficult to sell (the high-street bookshops don’t know where to place them to grab readers’ attention). Should you mimic the mainstream publishing industry's editorial process? Mimicry will bring you quality – there’s no doubt about that. It’ll also require a major investment in time and money. We all have to make difficult choices about what we do to make the things we create the best they can be. But there are limitations. I’m passionate about the independent author’s right to write, and I know that your pockets aren’t bottomless. I hope this has shed some light on the mainstream publishing process! Until next time …

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

If you’re new to fiction copyediting (or proofreading), you might struggle to find the balance between changing, querying and leaving well enough alone.

Don’t beat yourself up – even experienced editors labour to find an equilibrium at times, especially those who work with a stream of new-client authors.

Here are 5 tips to help you be a query superhero! And if you fancy downloading them to your preferred device, there’s a PDF at the bottom of the post.

1. Is it meant to be real or imagined? By definition, fiction is made up. There might be people, places, landmarks, buildings, even entire worlds that rest entirely in the mind of the writer. In that case, the author gets to make the rules (e.g. on spelling, environment, even physics) and our job is to check for consistency. Sometimes, though, the people, places, landmarks and buildings exist in the real world. And when there’s a discrepancy (Obama vs Obamah; Elizabeth Tower vs Big Ben) two possibilities emerge: (1) the author has slipped up; (2) the author has deliberately decided to bend reality a little, for any number of reasons. Querying, rather than changing, is essential.

Here’s an example from one of Amy Schneider's fiction-editing master classes:

Example

Schneider tells of a book she edited where the author had included mention of a New York newspaper. She fact-checked it; it had been a real newspaper, but had long ceased to exist by the time the year in which the novel was set had come around. It turned out that this was a deliberate decision on the part of the author, who for personal reasons wanted to keep the paper going in his fictional world. Tactful querying and discussion prevented embarrassment and harm.

LESSON: There’s real, and then there’s really real! Either may be required.

2. When the facts have changed Editors have a wealth of free online research tools at their fingertips. I can’t imagine doing this job thirty years ago! Still, even if we fact-check we might not access ALL the relevant information. Again, tactful querying rather than changing is usually the best way forward. Here’s an example of how my due diligence wasn’t diligent enough. Querying rather than changing saved me:

Example

I copyedited a crime novel in which a character was arrested and his rights were read out to him by a police officer. The wording seemed off to me so I fact-checked. I found what I thought was the correct wording and suggested (rather than changed) a possible recast for the author to use if he thought it appropriate. Good job, too. The author came back to me saying that the wording of the rights had changed in 1994, and that the original was correct given the year in which the scene was set. A big whoops moment for me and a lesson learned. Still, he thanked me for asking first. I still get the shudders thinking about the harm I would have done if I’d actually amended the text directly.

LESSON: Watch your historical context – your diligence needs to be deep enough to take account of it.

3. Be a problem solver Many of my indie authors haven’t taken their books through editorial review, developmental editing and substantive line editing before the file hits my inbox. I do make it absolutely clear what’s included in my service, but sometimes a client might not realize where some of the problems are, or, even if they do, might be stuck on how to fix them. This is where the query needs to go beyond a question and offer a solution. Fiction copyeditors are a little like mechanics, though I have a car so I know what it’s like to sit on the other side of the fence. When I take my car into the garage, I don’t expect to hand over 500 quid (or whatever) in exchange for a list of what’s wrong with my car. I do want to see that list, but I also want to know that the mechanic has solved the problems. For that reason, I think it’s good practice to explain the problem and offer a recast in the comments if we come across a sentence that we feel could do with tightening up or smoothing out. That way, the author can do a simple copy and paste if they like what we’re offering. Even if they don’t like it, it gives them another way of thinking about the text and how they might revise it to solve the problem in their own way (though see ‘Consider your own voice’ below for a cautionary tale!). This example from Erin Brenner (‘Writing Effective Author Queries’), with her author’s hat on, is frightening but illuminating:

Example

'I had a lot of comments that simply said: AU: Revise? No text was changed. No specific words or phrases were highlighted. The entire sentence bore the comment “AU: Revise?” It drove me mad. Revise what? In what way does this sentence need help? For each “AU: Revise?” I had to guess what the copyeditor might have taken issue with. Was everything grammatically correct? Had I missed a style point? A usage rule? How was the sentence not right? As copyeditors, we must remember that when we query, we have a goal: to get the author to make a change we think will help the text. Some authors will easily do so, others won’t. But no author can make corrections if he or she doesn’t know what corrections are wanted.’

LESSON: Problems without solutions (or even explanations) are next to useless for the author. Avoid!

4. Or be an adviser Back to the garage. Sometimes there are problems on the list that the mechanic can’t handle. Again, the same thing can happen to fiction copyeditors whose indie authors would have benefited from developmental work beforehand. And in that case the best we can do is suggest where to go for help. Here’s another example from my own back yard:

Example

I was hired to copyedit what turned out to be the most gorgeous thriller with a generous dose of humour included. The author made me laugh out loud several times in the first four chapters, and in the fifth he made me cry (not with laughter, but because the scene was so moving). I mention this because it’s an indication of how strong the writing was. Most of my edits were mechanical – standardizing dialogue punctuation, dashes, number treatment, spelling, punctuation and grammar. But, every now and then his point of view got a little sticky. POV isn’t something that’s covered by my service and I’m neither trained nor experienced in developmental editing. Nevertheless, I was able to solve the issue elegantly on several occasions because of the context in which the problem arose. However, there were several occurrences that I couldn’t fix. All I could do was flag them up for him, explain why I thought there might be a problem, and offer advice on where to go for help. It wasn’t an ideal situation for either of us, but at least I’d offered guidance. Sometimes that’s the best we can do.

LESSON: Second best sometimes has to suffice. If you can’t fix it, suggest who can.

5. Consider your own voice Given that we’re being paid for our services, our authors need to know that we’re their advocates, and that we’re there to elevate their writing, not criticize how they write. Says Sheila Gagen, ‘… the editor’s task is to serve readability (not, as some authors might think, to hack away at text or, as some editors might think, to point out where an author is wrong). The author wrote the text; he or she must have thought that it did make sense’ (‘The Art of the Editorial Query’). Queries therefore need to have a tone that shows respect and advocacy. Gagen also makes an important point about authors’ varying preferences – how not everyone wants to be hugged and handheld. The thing is, this is tricky to manage unless you’ve worked with the client on previous occasions. Here’s her story:

Example

‘Twice in my career, authors responded to my queries with the same word: “Duh.” (One even took the time to handwrite it in all caps with a few exclamation marks.) Both of those suggested changes were valid, but the authors were sick of my queries and gave up. As a result, they didn’t just lash out at the particular remarks they didn’t like … they ignored other, indisputable edits.’

LESSON: Be an advocate and watch your manners! Choose elevation over criticism.

Gagen recommends discussing the issue before the project starts. It may be that a writer will prefer you to just go ahead and make a substantive edit to the text. Others may want a nudge. Others will prefer a more detailed explanation in the comments. And given that we’re trying to help our authors avoid reader disengagement, it would be a shame if, through hitting the wrong tone, we ended up disengaging our clients. Adrienne Montgomerie offers further food for thought: ‘When you’re worn out, incredulous, and exasperated, it can show in your queries.’ Eek! To think that, despite our best efforts at advocacy, we might have made our author feel we’re no longer on their side, is unthinkable, and yet it can happen. She offers a handy list of different phrases you might consider when querying to keep your author engaged and your tone on track (‘10 Ways to Word a Sensitive Query’). I hope you’ve found these tips useful. Here’s your PDF mini-booklet if you fancy downloading the post to your device. Just click on the image to get your copy.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

If you’re new to writing and self-publishing, I have a tip for you – one that will save you a major headache as you work through the initial writing and later redrafting stages of your novel ... Create your own style sheet!

|

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed