|

Does your novel’s narrative have several consecutive snippets of dialogue that reflect a non-viewpoint character’s state of mind? If so, how do you punctuate them? And is there an alternative to using speech marks?

|

|

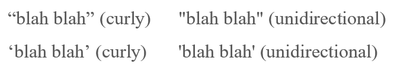

Parentheses

|

Tell me about parentheses (round brackets) and how they work.

|

|

Commas

|

Tell me about parentheses, round brackets, and how they work.

|

|

Spaced en dashes

|

Tell me about parentheses – round brackets – and how they work.

|

|

Closed-up em dashes

|

Tell me about parentheses—round brackets—and how they work.

|

Parentheses as convention breakers in fiction

This might be because they’re large and therefore visible marks – ones that demand a reader’s attention. That they’re interruptive could be a good reason to avoid them, though it could equally be the very reason why you want to use them.

The key to using any punctuation mark effectively is to understand its purpose and consider how the reader will interpret it. And so just because the use of parentheses is infrequent enough in fiction to make it unconventional isn’t a reason to ban them from prose.

Parentheses as satirical and viewpoint-switch markers

- For satirical purposes – an external narrator wants to poke fun at a focus character’s behaviour, thoughts or dialogue.

- For viewpoint purposes – the narrative is written from a viewpoint character’s perspective and therefore limited to their experience, but an external narrator wishes briefly to interrupt.

If you’d like to explore my analysis of these two uses, read How to use round brackets (parentheses) in fiction writing.

Scroll through the comments on that post and you’ll see a fantastic question raised by a reader that got me thinking about parentheses again.

The question an author posed

‘Louise, I'm writing a short story in which I have inserted a couple of parenthetical phrases (I don't even know what to call them) which separate one part of a sentence from another. I've seen Stephen King do this and it fascinated me. The character (narrator) is reflecting on a dream she has just awoken from. What do you think of this style, and what is it called?’

I replied admitting that I didn’t know quite what this is called in terms of literary style but that she’d got me thinking, and helped me consider a third function of parentheses that I hadn’t interrogated before: simultaneity.

Here’s her example. It’s from a short story tentatively titled ‘The Woman at the Window’.

(the bombs bursting in air)

bombs that were dropping by the hundreds from a fiery sky.

There are a couple of interesting things going on in Ellen’s example – not just the parenthetical phrase but also the placement of it. It takes its own line, which makes it stand out even more.

Why parentheses can convey simultaneity

‘I wanted to shake the reader up a bit by writing it that way,’ she told me.

And she succeeded. Parentheses do stand out. So does the separate line. But my reading of her work led me to consider another effect she’d created, albeit unwittingly – simultaneity.

How readers process sentences in a linear fashion

This is linear description. We absorb the story in the order the phrases are presented to us – first the dreaming, then the waking-up on a night just before Labor Day, then the terrified screaming, then seeing the exploding missiles, then the glare of the rockets, and finally the flaming sky.

But actually, that’s not how Ellen wrote it. Here’s the unedited version:

(and the rockets' red glare)

and the sky alight with flames.

The rocket-glare phrase is now bracketed and takes its own line. And I think this changes that linearity subtly. It’s as if the glare of the rockets is experienced at the very same moment that the missiles are exploding. It’s another layer of experience that sits behind the explosions.

That’s how we often experience traumatic events in reality. Our brains work so fast that we process multiple pieces of information and feel multiple emotions all at once. The difficulty comes in expressing that in linear text.

In Ellen’s example, the parentheses act as a signal of this simultaneity of experience, and show rather than tell an onslaught of emotional, auditory and visual information.

Showing sensory assault through simultaneity

(the bombs bursting in air)

bombs that were dropping by the hundreds from a fiery sky.

The way the parenthetical phrase punctuates the prose makes me feel uncomfortable. It jars me visually. And that’s why I love it. It shows rather than tells the assault on the senses that I can imagine a person would experience if they were in an environment where missiles were exploding and falling around them.

The character awakes. She’s likely still shaken from the dream, and trying to process what she experienced. And so she narrates what she saw, which pared down is this:

But as she's thinking about this, the bursting bombs is there too, behind the more expository narration, right at the same time. And it’s the bracketed line that shows this.

An alternative might have been:

In that revised version, 'as' tells the simultaneity. It's told prose. Instead, Ellen as author, has shown us with the parentheses, and it's far more dramatic.

And so we might consider parenthetical statements such as this as devices that help authors create layers of simultaneous experience that are warranted when there’s sensory assault in play.

Showing conflict through simultaneity

Here’s an example that I have written more conventionally, using italic and a tag to convey a thought.

Say no, she thought. You don’t have time.

Yes yes yes yes, she typed, because it would be a crap ton of fun and the alternative was D asking someone else, and that was unthinkable.

This approach encourages the reader to approach the prose in a linear way: First D texts Louise with an idea. Then a thought process takes place. Then Louise responds.

But look what happens when we experiment with parentheses.

(Say no. You don’t have time.)

Yes yes yes yes, she typed, because it would be a crap ton of fun and the alternative was D asking someone else, and that was unthinkable.

Now there’s a signal that two conflicting emotional responses are in play simultaneously. Thinking ‘no’ and typing ‘yes’ are occurring at the same time.

Summing up

However, used purposefully, parentheses can enhance that moment and create a sense of simultaneity of experience – perhaps involving an assault on the senses or competing emotions fighting for primacy in a character’s mind.

There are no rules in fiction. Instead, what writers (and the editors who work with them) must strive for is how best to communicate a character’s emotions, perception and actions in the moment, so that the reader can get under the skin of that experience.

And it might just be that – once in a while – a pair of round brackets helps with that goal.

Other resources you might like

|

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

This post looks at problematic language, the messages it might unintentionally convey, and how we can talk about the editorial conundrums we come across without judgement.

Embedding the language of preference in editorial discussion

- ‘What’s the correct way to punctuate this sentence?’

- ‘Is the grammar in this sentence right?’

- ‘What’s APA’s rule for hyphenating [...]?’

The problem with notions such as ‘right’, ‘correct’ and ‘rule’ is that they’re loaded. The implication is that there’s one way – a best way – to write and to edit.

In reality, there are multiple ways to punctuate a sentence, each of which could alter its flow and rhythm in nuanced ways.

There are multiple Englishes, too, each with grammatical and syntactical structures that vary from region to region within nations as well as from country to country.

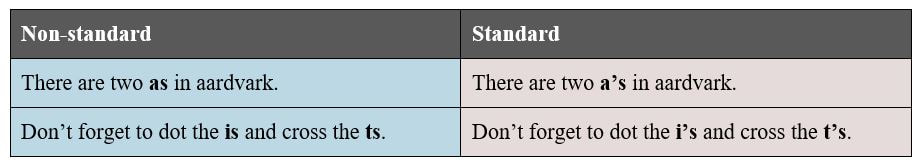

And there are multiple style guides that express particular preferences.

All of which means there is no ‘correct’ way to punctuate a sentence, no ‘right’ grammar, and no ‘rule’ on hyphenation. What there are instead are conventions and choices that that can be implemented or ignored.

Instead, we could ask:

- ‘How can I punctuate this sentence to convey urgency? The author’s used commas but I’m wondering if spaced en dashes would be effective.’

- ‘Is the grammar in this sentence distracting or is the sense clear? The narrator is from [...] but I’m not.’

- ‘What’s APA’s preference for hyphenating [...]?’

The artistry of editing lies in helping the client craft prose in which the meaning is clear and interpreted as intended by readers. Embedding that principle – rather than the language of rights and rules – in the way we talk about our work means we’re more likely to think descriptively rather than prescriptively.

Whose standards and conventions are in play?

- How words are spelled in various Englishes

- How dialogue is punctuated

- Whether a term is hyphenated

- How apostrophes convey possession or omission

- Whether to place full points after contracted forms

- Whether the first paragraph in a section is indented or not

- The grammatical structure of a sentence

- How verbs are conjugated

When we come across writing that doesn’t conform to these standards and conventions, some of us choose to refer instead to ‘non-standard’ language and ‘breaking from convention’ so as to avoid the judgement embodied in terms such as ‘right’, ‘best’, ‘correct’ and ‘rule’.

It’s been my preference because I felt it was more neutral and framed the issue around reader expectation rather than my own lived experience of language.

And that’s something I’ve been thinking about.

Why? Because these terms, too, need to be used with caution. We need to be aware that while standards and conventions help readers make sense of the written and spoken word, they are created and enforced by those with advantage, those who have the power to deem them as standard and conventional in the first place, and to assert their primacy.

That doesn’t make those standards and conventions better; it just means those who define them are in a position to do so. It also means that prose can be just as rich when those standards and conventions are ignored or flexed.

What about style guides?

Mindful editing means remembering that these preferences aren’t ‘right’ or ‘better’. They’re certainly not rules. Even Oxford’s New Hart’s Rules isn’t a rulebook! Rather, these are useful guides that help editors and authors bring clarity and consistency to writing.

However, editors – particularly those working on creative texts – need to be ready to bend when character and narrative voice would be damaged by prescriptive application of a style guide.

As for those of us working on texts that deal with identity and representation, we need to be ready to question the advice in a published style guide; it might be behind the curve.

Transferring judgement to the client

An author might not write in sentences that follow grammar, spelling and punctuation conventions, but that in no way means they’re a poor crafter of prose. Perhaps the way they lay down words is because they haven’t learned our conventions. Or perhaps they’ve actively chosen to ignore those conventions because that style of language doesn’t suit their character and narrative voices.

The mindful editor needs to recognize and respect both scenarios. Understanding which one is in play is critical because it will determine whether and which amendments are suggested, and why.

‘Wrong’, ‘non-standard’ or authentic voice?

These excerpts are from the opening chapter of Imran Mahmood’s You Don’t Know Me (pp 4–5; Penguin, 2017).

[…]

He don’t know what I know. The problem for me was that although I know what I know, I don’t know what he knows. Do I let him speak to you in your language but telling only half the story, or do I do it myself and tell the full story with the risk that you won’t understand none of it?

Are the words I placed in bold ‘incorrect’ or ‘wrong’? That’s a judgemental approach that implies there’s a single perfect, right way to write and speak English. There isn’t.

Are the terms ‘non-standard’? To my ear, yes, some of them are, but that’s because I’m a 54-year-old middle-class white woman raised in Buckinghamshire, England, who was taught how to write and speak according to a standard dreamt up by … actually, I’m not sure who dreamt up the standard but it was probably someone who looked, spoke and was educated quite a lot like me and had the advantages I have.

Rather than thinking about these excerpts in terms of whether some of the words are non-standard or standard, instead we can evaluate them in terms of voice. Rich, evocative voice.

Our first-person narrator has been accused of murder and has elected to defend himself. As the blurb on the back cover says: ‘He now stands in the dock and wants to tell you the truth. He needs you to believe him. Will you?’

Actually, it’s his authentic voice that draws me – a 54-year-old middle-class white woman raised in Buckinghamshire, England – deep into his psyche so that I can see and hear him as if we are one. And that means I can root for him, invest in him, care about him, believe him.

Thinking about that narrative in terms of whether it’s ‘correct’ or ‘right’ would be butchery. To apply a digital red pen to it would be a crime.

And even those of us who might apply the term ‘non-standard’ to the emboldened words must acknowledge that such prescription is based purely on our own lived experience of English – how we write, how we speak, and what we were taught. That doesn’t make our way of speaking and writing better or worthier.

When story and characters drive language, readers will come along for the ride, regardless of their lived experience. When prescriptivism is behind the wheel, readers will disengage and find a different journey to take.

Framing errors in terms of author intention and reader expectation

Regardless, the focus here is on intention, and for that reason there are times when it’s appropriate for the editor to use the term ‘error’.

When editors are tasked with finding errors, they’re looking for what wasn’t intended in that particular project. Take a look at these four examples:

- “Are the autopsy results in yet?’ Milburn asked.

- Xe put xyr pen on the table and frowned. No way was he letting that one pass.

- She hears him clearly – banging on again about how their from out of town and don’t know their way around.

- ‘I wanted to call the police but Johnny ‘One Sock’ Swainston wasn’t having any of it.’

We can say without judgement that there are four ‘errors’ in the above examples because in each case the author likely made a mistake – they meant to use a consistent style of speech marks in the first example, meant the pronouns to be consistent in the second, meant to use ‘they’re' in the third, and meant to use an alternative style for the nested quotation marks in the fourth.

When we’re querying potential errors, however, we can still use the language of intention and reader expectation in our comments, thereby avoiding a more critical tone:

- Did you mean to write […] here or is this a typo?

- How about [...] instead? This would be less likely to distract the reader, who might be more used to seeing [...] and therefore misinterpret what you've written.

- The grammar in this section doesn’t align with your usual narrative voice, and reads more like something Character Y would say. Is this intentional? If not, how about trying [...]?

Summing up

- Saying something’s ‘right’ might imply that all alternatives are wrong when they aren’t.

- Defining something as a ‘rule’ might imply that breaking it is non-conformist, eccentric, non-compliant, even disobedient.

- Referring to something as ‘standard’ normalizes the preferences of those who have the power to make that decision in the first place.

Instead, we can frame our discussions and queries around meaning, author intention and reader experience. That way, we’re putting the prose where it belongs – front and centre.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Some writers and editors love a rule. I’m not so keen on the language of ‘rules’ because it sets up a binary mindset that’s focused on ‘wrong’ versus ‘right’ rather than clarity of meaning. Instead, I prefer to think in terms of convention.

Grammatical conventions are useful and purposeful. They provide us with a common frame of reference that helps us communicate clearly through the written word. We can start by at least acknowledging the following:

- Breaking with convention requires understanding convention’s intent.

- However, ignoring convention doesn’t always render a sentence unreadable or misunderstood.

- And adhering to convention doesn’t always mean a sentence is as powerful as it could be.

Balancing convention and meaning

Writing and editing fiction requires deciding when to break with convention. But how do we work out what works and what doesn’t? Here’s how I frame the balancing act:

- Punctuation should serve meaning as long as that doesn’t butcher rhythm.

- Rhythm should serve emotion as long as that doesn’t butcher understanding.

- Both should serve the reader and the story rather than the style manual and the grammar book.

So how does that apply to commas, coordinating conjunctions and independent clauses?

What are coordinating conjunctions?

Coordinating conjunctions are words that join other words or groups of words of equal weight. You might see them referred to in short as FANBOYS:

|

Independent clauses are groups of words that can stand as a sentence on their own and still make sense. They include a subject and a predicate.

Subjects are people/things that are doing something or being something – the noun (the thing) and the adjectival information describing that noun. The four examples given below are all subjects.

- Louise

- That fiction editor Louise Harnby

- The dog

- The Labrador in the corner

Predicates are what they’re doing – the verb (the doing word) and the thing the verb’s acting on. The four examples below are all predicates.

- slumped over the desk.

- loves working on thrillers.

- licked its paws.

- is pale yellow.

Joining subjects and predicates gives us independent clauses. Here are two simple examples (subject in bold; predicate underlined).

- The dog is pale yellow.

- It is licking its paws.

If two or more independent clauses in a sentence are joined by a coordinating conjunction, it’s conventional to place a comma before that conjunction.

EXAMPLE AND EVALUATION #1

In the following example, the independent clauses are in bold.

The independent clauses could stand on their own as complete sentences and be understood perfectly well. Let’s revisit our balancing act and assess the impact of the comma.

The degree to which the comma serves meaning here is, I think, debatable. This is what it looks like without the comma:

There’s no ambiguity there, and so one could argue that insisting on a comma would be grammatical pedantry. An editor would struggle to justify adding a comma for any other reason than ‘that’s the rule’ or 'I think it looks better' because the meaning is perfectly clear.

Could someone argue that the comma enforces the equal weighting of the independent clauses lying either side of the coordinating conjunction?

Yes in that it acts as a separator of two ideas: the dog’s colour and what it’s doing to its paws; the one isn't related to the other. And so I certainly wouldn’t remove it if it were already in place; there’s no justification for such an action.

MORE COMPLEX CONSTRUCTIONS

Many sentences in fiction are more complex. If our example looked like this, we might have a sounder justification for adding the comma:

In the revised example below, I think applying the conventional punctuation helps. The rhythm is moderated – we take a little breath when we reach the comma – and experience (through our viewpoint character’s eyes) first the colour of the dog and then what it’s doing and why.

The two ideas have a starker separation, and the punctuation convention supports that meaning.

EXAMPLE AND EVALUATION #2

Here’s an excerpt from Robert Ludlum’s The Janson Directive (Orion, 2003, p. 355). Once more, both independent clauses are in bold.

The independent clauses could stand on their own as complete sentences and be understood perfectly well. Again, let’s revisit our balancing act and assess the impact of the comma.

I think the comma serves meaning and is necessary. Without it, we might start to read the sentence as if the slug would shatter not just a skull but another life too. That’s not what Ludlum is saying. Instead, we’re alerted that another idea is coming into play.

A trip-up here means the reader would have to fix the grammar in their head and reread the sentence to make sense of it. That’s a momentary distraction no writer wants.

Let’s have a look at when we might ignore grammatical convention.

Below is a short scene I’ve made up. Our protagonist is a forty-year-old woman having a nightmare about a past event.

I wake, slick with sweat, the six-year-old me hovering spectre-like in my mind’s eye. It’s the third time I’ve had that dream in the past week.

There are three independent clauses (and the start of a fourth) linked by a coordinating conjunction. The ‘rule’ says there should be a comma before all those ‘and’s.

EVALUATION

A pro fiction editor would want to think twice before they start adding in commas because of some rule or other.

- First of all, we need to recognize the literary device in play here – anaphora: deliberate repetition for the purpose of emphasis or meaning – in this case ‘and it’s’.

- Notice, too, how the beats in those independent clauses are similar: dee-dum-da-dum, dee-dumdum-da-dum, dee-dumdum-dada-dum.

Using anaphora doesn’t mean we have to ignore commas, far from it. But what would introducing them do to rhythm and mood?

I think the lack of commas helps us to feel our way under the skin of that dream-child because young children in a panic don’t introduce pauses or moderate their speech according to a style manual or a grammar guide. Instead, words fly from their mouths like tiny storms.

What we have instead is the sense of terrified disorientation being experienced by the dreamer, one that’s shown rather than told.

Commas would moderate the pace and separate the ideas contained in each independent clause; omitting them means we’re offered a stream of terrified consciousness.

Some grammarians do allow for an exception when the independent clauses are short and closely related.

In the examples that follow, the coordinating conjunctions are underlined; notice the absence of the preceding comma. Sense isn’t marred because of the missing punctuation.

- The gig was finished but no one seemed keen to leave.

- ‘You need to return that or the boss is going to fire you,’ said Harvey.

- She’d told him three times yet he wouldn’t listen.

- The dog is almost white so it stands out in the dark.

- Mara was late yet again and Aisha was furious.

It’s an eminently sensible exception – one that allows for decluttering but also avoids a separation of ideas that isn’t appropriate.

- In the first example, ‘no one seemed keen to leave’ is an independent clause, but the reason for telling us this rests on the gig being finished. No comma required.

- In the fifth example, Aisha’s fury is standalone, too, but it’s a result of Mara’s tardiness. No comma required.

Summing up

The grammatical convention of placing a comma before a coordinating conjunction linking independent clauses is helpful and useful. However, sometimes we can omit those commas:

- Because the comma interrupts rhythm and emotion, and therefore shown meaning.

- Because the meaning is clear, and a comma would be unnecessarily cluttering.

- Because the comma introduces an inappropriate separation of ideas.

Style and grammar resources offer guidance, and we should use them, but only in so far as they serve the reader and the story, not because we are rule enforcers. That’s nothing more than a road to literary butchery.

More resources to help you line edit with confidence

- Author resource library (includes links to free webinars)

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level: A Guide for Beginner and Developing Writers

- Making Sense of Punctuation: Transform Your Fiction 2

- ‘Playing with sentence length in crime fiction. Is it time to trim the fat?’

- ‘Playing with the rhythm of fiction: commas and conjunctions’

- ‘What is anaphora and how can you use it in fiction writing?’

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Listen to find out more about:

- What exclamation marks look like

- Functions: Surprise, emphasis, volume

- How many to use

- Social media use

- Reasons to omit them: web, business academic copy

- Balancing use and abuse

Editing bites

- How to Fix Your Damn Book, by James Osiris Baldwin, CreateSpace, 2016

- Purdue OWL

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

What is a comma splice?

When two independent clauses – which could stand on their own as sentences and make perfect sense – are separated by a comma, the sentence is said to contain a comma splice. For example:

- I love tomatoes.

- Red and yellow ones are my favourites.

Those two sentence above could be separated by a semi-colon, a dash, or a full stop and no one would be breathing grammar rules down your neck:

Standard punctuation

- I love tomatoes; red and yellow ones are my favourites.

- I love tomatoes – red and yellow ones are my favourites.

- I love tomatoes—red and yellow ones are my favourites.

- I love tomatoes. Red and yellow ones are my favourites.

However, if you use a comma to separate them, that heavy breathing will come from some quarters:

Non-standard: comma splice

- I love tomatoes, red and yellow ones are my favourites.

Why comma splices trip up readers

Some people don’t know what a comma splice is and don’t care. But plenty do, and even if they don’t know what’s it called, they trip up. For those in the know, comma spliced sentences (sometimes) scream off the page for precisely that reason.

That's because when readers see a comma they're inclined to think, This is the start of a list.

A standard method for showing a reader that they’re coming to the end of a list is to incorporate a coordinating conjunction such as ‘and’, ‘but’, ‘though’ and ‘or’. It acts as shorthand for One more item’s coming. Then there’ll be a full stop.

And so when only two items are separated by a comma, the reader’s expecting at least one more item in that list. When that third item doesn’t appear and the sentence finishes, the reader is jolted because they've placed the emphasis in the wrong place. Try reading these examples out loud:

- Let me tell you about fruit: I like apples, I hate pears but I think oranges are okay. Are we clear now?

- Let me tell you about fruit: I like apples, I hate pears. Are we clear now?

Your intonation likely changed as you read the words 'but I think oranges are okay' because you knew you were finishing a sentence. In the second example, you were left hanging after 'hate pears' and likely hadn't placed the stress correctly.

These kinds of stumbles are a distraction that, even if only for a split second, pulls the reader out of the writing. Now they’re thinking about where they placed the emphasis, not about our fabulous learning tool, enthralling plot line or groundbreaking academic research.

When comma splices can work: fiction

Comma splices are probably more prevalent in published fiction, and more acceptable. Sometimes, and with good reason. The comma doesn't always trip up readers.

The key is to allow splices to stand when they serve a purpose.

Narrative and rhythm

Take this example from A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens: ‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity’ and so on.

This prose is an experiment in rhythm. The splices work. But something else is going on too – the anaphora.

Anaphora is a literary device that uses repetition for rhythmic effect. In the Dickens example, the repetition of 'it was' pulls us along on a beautiful booky wave. Editing in semi-colons or full points would destroy the rhythm and would qualify as an example of editorial hypercorrection.

For a more detailed examination of anaphora, read: What is anaphora and how can you use it in fiction writing?

Dialogue and mood

While a comma splice will stick out like a sore thumb in a piece of academic research or an education textbook, that’s not always the case in dialogue.

If the speech is truncated, or there's anaphora in play, a comma might well work. Imagine this scenario in a novel: two characters are having an argument. One says, ‘It’s not me, it’s you’.

Strictly speaking, that's a comma splice. There are two independent clauses with a comma. Would it bother you? Probably not. The speech looks and sounds natural to the mind's ear. Changing the comma to a full stop would slow down the rhythm of the character’s speech and affect the emotionality in the dialogue.

But most important, readers won't trip up; they'll place the emphasis correctly. And so while emotion and mood have been respected, this hasn't been at the expense of clarity.

Summing up

- Understand what a comma splice is. Only then can you make an informed decision about whether to let it stand or fix it.

- Read the sentence aloud, tor ask someone else to. If you or they stumble over what you’ve written, so might your reader.

- Just because Woolf, McCarthy and Dickens use comma splices doesn't mean every writer should. There may be other literary devices in play or narrative motivations affecting their choices.

- There is a grammatical standard for how commas are handled between two independent clauses, but even so, we can’t prescribe for always right or always wrong. Sometimes it’s about style, rhythm and flow.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Find out more about

- Direct questions

- Indirect questions

- How-to statements

- Idiomatic phrases and question marks

- Double punctuation

- Uncertain dates and date ranges

- Indicating uncertainty

Mentioned in the show

- But Can I Start A Sentence With “But”? by Carol Saller

- Making a Point: The Pernickety Story of English Punctuation by David Crystal

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

- What quote marks are used for

- Omitting a closing quote mark in dialogue

- Whether to use single or double quote marks

- Whether to use straight or curly quote marks

- Where the closing quote mark goes in relation to other punctuation

- When not to use quote marks

What quote marks are used for

Quote marks are used in 3 ways in fiction:

- Character dialogue

- To distance the narrator from what's being reported

- To denote song titles and other works

Character dialogue

Quote marks show that we’re reporting what someone else is saying or said.

Each new speaker's dialogue should appear on a new line and include opening and closing quote marks.

To distance the narrator from what's being reported

The tone of the distancing rendered by the quote marks will depend on narrative intent. Perhaps the voice is sarcastic. Or the author might want the reader to suspend belief by indicating that a character considers a word or phrase unreliable.

Imagine the character is saying so-called or supposed or allegedly before the word in quotes.

Peter almost laughed. The last time his 'friends' had phoned or visited had been over six months ago. Two had wanted money, Another needed business advice. A fourth had spent the evening flirting with his now ex-wife.

A word of caution: Don't be tempted to differentiate distancing terms in the narrative from dialogue by using an alternate style. If there are double speech marks around the dialogue, there should be double marks around the distancing words.

"What about your friends? Didn't they help?" Molly said.

Peter almost laughed. The last time his 'friends' had phoned or visited had been over six months ago. Two had wanted money, Another needed business advice. A fourth had spent the evening flirting with his now ex-wife.

STANDARD (USING DOUBLES AS BASE STYLE)

"What about your friends? Didn't they help?" Molly said.

Peter almost laughed. The last time his "friends" had phoned or visited had been over six months ago. Two had wanted money, Another needed business advice. A fourth had spent the evening flirting with his now ex-wife.

To denote song titles and other works

Quote marks are also used to identify certain published works such as song titles and book chapter titles.

So, for example, if a writer is referring to an album or book title, this is rendered in italic. However, when it comes to a song on an album, or a chapter in a book, it's conventional to use quote marks.

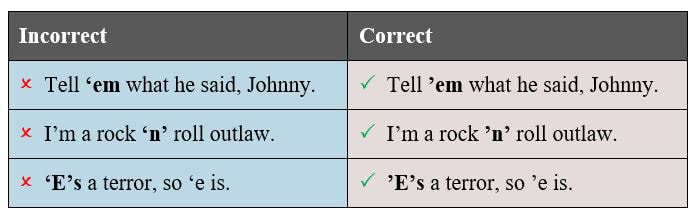

Omitting a closing quote mark in dialogue

There's one occasion where it's acceptable to omit the closing speech mark in dialogue: same speaker, new paragraph.

So, if you want your dialogue to take a new paragraph while retaining the current speaker, use a quotation mark at start of the new line but omit the closing one at the end of the previous paragraph.

|

‘[…] My father described the regular pom-pom-pom of the cannons and the increasingly high-pitched wails of the planes as they dived. He said he’d heard them every night since.

‘The last day of the battle he was standing on the bridge when they saw a plane emerging. […] Then he jumped overboard and was gone.’ The Bat (p. 251), Jo Nesbo, Vintage, 2013 |

Single versus double quote marks

There’s no rule, just convention.

There are lots of Englishes: US, UK, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand, South African, Indian, etc. Each has its own preferences and idiosyncrasies.

Focus on which English your audience will expect, and punctuate your writing accordingly. Whichever style you choose, the main thing is be consistent.

- In the UK, it’s more common to use single quote marks. And if there’s a quote within the quote, that’s a double. You might hear quotes within quotes called nested quotes.

- In US English it’s conventional to use double quote marks with nested singles.

|

Ray studied his drink and narrowed his eyes. ‘You can be cruel sometimes, you know. I don’t know where you got it from. “How sharper than a serpent’s tooth …” Your mother didn’t have a cruel bone in her body.’

Sleeping in the Ground (p. 261), Peter Robinson, Hodder & Stoughton, 2017 “I had no idea why he was bringing that up now. So when I asked him he said, ‘Remember when the going got tough, who was there for you. Remember your old man was right there holding your hand. Always think of me trying to do the right thing, honey. Always. No matter what.’” The Fix (p. 428), David Baldacci, Pan Books, 2017 |

If you choose double quote marks, use the correct symbol, not two singles.

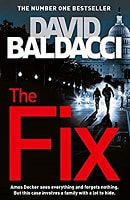

Straight versus curly quote marks

Curly quote marks are more conventionally known as smart quotes.

It’s conventional in mainstream publishing to use smart or curly quotation marks, not unidirectional ones.

- Go to FILE and select OPTIONS

- Select PROOFING, then click on the AUTOCORRECT OPTIONS button

- Choose the AUTOFORMAT AS YOU TYPE tab

- Make sure there’s a tick in the "STRAIGHT QUOTES" WITH “SMART QUOTES” box

- Click on OK

If you’ve pasted material into your book from elsewhere, or you didn’t check autocorrect options before you began typing, there might be some rogue unidirectional marks in your file. To change them quickly, do a global find/replace:

- Select CTRL+H on your keyboard to open FIND AND REPLACE

- Type a quotation mark into the FIND WHAT box

- Type the same quotation mark into the REPLACE WITH box

- Click on the REPLACE ALL button

The closing quote mark in relation to other punctuation

In fiction, punctuation related to dialogue is placed similarly whether you're writing in US or UK style: within the quote marks.

Here are some examples:

- "Don't move a muscle," Stephen said.

- "My God! Is that Jonathan? He looks fabulous."

- “Maybe you don't think we've met but I can assure—”

- Dave glanced at the signature tattoo on the Matt’s hand. ‘That looks familiar. Who inked you?’

- ‘Never.’ I sized up the door and the window. ‘I love you ...'

However, there's a difference when it comes to distancing or cited works. Note the different placement of the commas and full stops in the US and UK examples. In US English, the commas come before the closing quotation marks; in UK English, they come after.

- US English convention: Peter's "friends," the ones who hadn't bothered to find out if he was okay after his wife ditched him, seemed oddly keen to get in touch now that he'd won the lottery.

- UK English convention: Peter's 'friends', the ones who hadn't bothered to find out if he was okay after his wife ditched him, seemed oddly keen to get in touch now that he'd won the lottery.

- US English convention: "Favourite Jimi Hendrix songs? 'Foxy Lady,' 'Hey Joe,' and 'Purple Haze.'"

- UK English convention: 'Favourite Jimi Hendrix songs? "Foxy Lady", "Hey Joe", and 'Purple Haze".'

When not to use quote marks

There are 2 issues to consider here:

- Thoughts

- Emphasis

Thoughts

CMOS at section 13.43 says you can use quote marks to indicate thought, imagined dialogue and other internal discourse if you want to. However, I recommend you don't. For one thing, I can’t remember the last time I saw this approach used in commercial fiction coming out of a mainstream publisher’s stable.

But the best reason for not putting thoughts in quote marks is because it might confuse your reader. The beauty of quote marks – or speech marks – is that they indicate speech. Let them do their job!

Emphasis

It can be tempting to use quote marks in your writing to draw attention to a word or phrase, but it’s rarely necessary and could even have the opposite effect to what you intended. It works instead as a distancing tool, as discussed above.

If you’re tempted to use quote marks for emphasis, imagine saying the sentence out loud, and making air quotes with your fingers as you speak. Would your character/narrator say it like that? If the answer's no, leave out the quote marks. Italic will work better. Or recast your dialogue so that the reader can work out where to place the stress themselves.

Summing up

If in doubt about how to use quote marks for your book, consult a style manual. I recommend the Chicago Manual of Style, the Penguin Guide to Punctuation and New Hart’s Rules, all of which offer industry-standard guidance.

If you'd prefer to listen to the advice offered here, Denise Cowle (a non-fiction editor) and I chat about how to use quote marks in all types of writing on The Editing Podcast. You can listen right here or via Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast platform

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

What are round brackets?

This is what they look like: ( )

They always come in pairs, and act as alternatives to paired dashes or commas in fiction. They have other functions in non-fiction writing but I’ll leave that discussion to a non-fiction editor!

Compare these examples:

- The red-nosed reindeer (Rudolph was his name) had a very shiny nose.

- The red-nosed reindeer, Rudolph was his name, had a very shiny nose.

- The red-nosed reindeer – Rudolph was his name – had a very shiny nose.

- The red-nosed reindeer—Rudolph was his name—had a very shiny nose.

All of the above are grammatically correct, though paired brackets (like dashes) are stronger than commas, and more interruptive to the eye than both commas and dashes, probably because they’re used less frequently and associated more with non-fiction work.

Every writer will do well to ask themselves how their choice of parenthetical styling will affect the rhythm and clarity of their prose.

Every writer will also do well to ask themselves whether readers will be annoyed by them. Like serial commas, adverbs and the singular they, round brackets rarely pass a reader or an editor without evoking opinion. More on that later.

Brackets, full points and capitalization

Regardless of which English you’re using – British or American, for example – the rule is the same:

- If the bracketed information is included as part of a sentence, the full point comes after the closing bracket. The bracketed clause takes a lower-case initial letter unless it starts with a proper noun.

- If the bracketed information stands as a sentence in its own right, the full point comes before the closing bracket. The bracketed sentence takes an initial capital.

Danger, Will Robinson!

Round brackets in fiction garner strong opinion, usually negative.

The most-cited reason I’ve seen – and it’s a valid one – is that they pull readers out of a story. Given that there’s no reason on earth why you’d want to pull a reader out of a story, tread carefully.

Still, given that they’re not grammatically wrong, it’s only right that we should consider the ways in which round brackets might work in your fiction. The two I’ve seen most often are as follows:

- Satire – narrators poking fun

- Viewpoint shifts – narrators interrupting

Round brackets in fiction: Satire

For an example of how round brackets can be used for satirical purposes, we need look no further than Dickens.

In Our Mutual Friend (Wordsworth Editions, 1997), the viewpoint is omniscient. The scene is an ostentatious banquet hosted by the Veneerings. Dickens uses round brackets to set off narrative asides that poke fun at the guests and show them as the bumptious fools he believes them to be – and wants us to.

Here’s an excerpt from p. 11:

In other words, the crest is a farce.

And one of the diners, a Mr Twemlow, is obsessed over whether he is Veneering’s ‘oldest friend’, though he would never admit to being bothered by such a thing.

Dickens’s bracketed snipe (p. 12) leaves us in no doubt about the man’s snobbery; it interrupts the dialogue of Lady Tippins, a frightful show-off whose ‘my dear’ sends Twemlow into a tizzy:

This approach is unlikely to find favour with readers who bought your high-octane thriller expecting a rollercoaster ride. The external narrator’s voice is overwhelming, and in most contemporary commercial fiction it will slow readers down, drag them out of the story, and infuriate them.

Round brackets in fiction: Viewpoint shifts

Take a look at this example from Stephen King’s The Outsider (p. 252; Hodder, 2018):

|

With that taken care of, Holly went down to the hotel restaurant and ordered a light meal (she never even considered room service, which was always ridiculously expensive). She found a Mel Gibson film she hadn’t seen on the in-room movie menu, and ordered it – $9.99, which she would deduct from her report of expenses when she filed it.

|

The brackets are effective here precisely because they’re interruptive. The narrative viewpoint in this section is third-person; we see the world as Holly, the private investigator, experiences it.

Given that it’s third-person, our finding out something that Holly hasn’t considered shifts the narrative distance. Such a shift might jar under other circumstances because it yanks us out of Holly’s head.

King, however, is a master of viewpoint, and he writes his characters with a rich immediacy. Still, he finds ways to introduce flexibility seamlessly, and in this case it’s with round brackets to introduce his omniscient narrator.

The parentheses allow an external narrator to enter the story just for a moment – an all-seeing eye that tells us what Holly didn’t think – but that voice is cocooned safely within those round brackets, and is gone as soon as the reader’s eye passes over the closing symbol.

King’s an experienced writer. If you’re not, I recommend holding a single character viewpoint and steering clear of bracketed interruptions from another narrator.

Here are four ways we could recast the King excerpt:

With that taken care of, Holly went down to the hotel restaurant and ordered a light meal – no way was she paying room-service prices.

Closed-up em dash

With that taken care of, Holly went down to the hotel restaurant and ordered a light meal—no way was she paying room-service prices.

Semicolon

With that taken care of, Holly went down to the hotel restaurant and ordered a light meal; no way was she paying room-service prices.

Full point

With that taken care of, Holly went down to the hotel restaurant and ordered a light meal. No way was she paying room-service prices.

Round brackets in fiction: Dialogue

In Fix Your Damn Book! How to Painlessly Self-Edit Your Novels & Stories (Gift Horse Productions, 2016), James Osiris Baldwin advises never using round brackets in dialogue because they break ‘the fourth wall’.

What’s the fourth wall? It’s originally a theatrical term but in our case refers to ‘The conceptual barrier between any fictional work and its viewers or readers’ (Lexico/Oxford Dictionaries).

It’s good advice. It makes no sense to give an external narrator space inside a character’s speech. That’s why in the earlier Dickens example, the interruption comes between the speech-marked dialogue rather than within it.

Summing up

There’s nothing grammatically wrong with using round brackets. Stylistically, however, they could be a misfire. If you use them in your fiction, think care and rare: understand the impact they have on story and viewpoint, and use them infrequently.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Dashes are sometimes referred to as ‘rules’, especially in the UK. Oxford’s New Hart’s Rules (NHR) refers to the ‘en rule’ and the ‘em rule’ whereas The Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS) discusses ‘en dashes’ and ‘em dashes’.

Both terms are acceptable but I’ll use ‘dash’ in this article.

A word on exceptions

Take a look at the likes of CMOS and you’ll see plenty of exceptions to the rules, which is why I don’t much like rules when it comes to fiction editing! What I’ve given you here is what I think you’ll need to know most of the time for most of your novel writing.

What do the dashes look like?

There are four dashes you’re most likely to use in fiction:

- Hyphen: -

- En dash: –

- Em dash: —

- 2em dash: ⸺

Dashes that set off text and replace alternative punctuation

The EN DASH and the EM DASH can be used to set off an augmenting or explanatory word or phrase in a sentence that could stand alone without the insertion.

Brackets, commas and colons can act as alternative forms of punctuation. Here are some examples that demonstrate how it could be done:

That old dog, the black one, is as sweet as they come.

That old dog – the black one – is as sweet as they come.

That old dog—the black one—is as sweet as they come.

She knew the name of that old dog – everyone did.

She knew the name of that old dog—everyone did.

That sweet old dog had a name – Patch.

That sweet old dog had a name: Patch.

In the UK, it’s conventional to use a SPACED EN DASH. This is not the law, not a rule, not the only way or the right way. It’s just the style that many UK publishers choose, though not all.

Here’s an example from my version of Stephen King’s The Outsider (p. 171):

In the US, it’s conventional to use a CLOSED-UP EM DASH. Again, this is not the law, not a rule, not the only way or the right way. It’s just the style that many US publishers choose, though not all.

Here’s what King’s sentence looks like when amended according to US convention:

Some style guides even ask for SPACED EM DASHES, though I see this usage less frequently:

I recommend you stick to spaced en dashes or closed-up em dashes in fiction because that’s what your readers will be most familiar with. As for which style you should choose, think about:

- where your target audience is based

- what they’re used to seeing

If you’re publishing internationally, pick one style and be consistent.

Dashes in number spans

In fiction, number spans are often written out, though again this is convention rather than a rule that must be adhered to. Number ranges might make their way into emails, texts, letters and reports in your story, and they’re perfect for date ranges.

A CLOSED-UP EN DASH between number spans is standard in publishing, whether you’re writing in British English or US English:

Morning registration: 9:30–11:30 (colons more often used in time styles in US English)

See pp. 86–95

The 1914–18 war was the war to end all wars

07/03/1967–26/06/2019 (day/month/year; standard in UK English)

03/07/1967–06/26/2019 (month/day/year; standard in US English)

Note that the en dash means up to and including (or through in US English).

CMOS and NHR both recommend using EITHER the closed-up en dash in a number range OR a from/to or between/and construction, but not a mixture of the two:

Read pp. 86–95 (standard)

Read from p. 86–95 (non-standard)

The war lasted from 1914 to 1918 (standard)

The war lasted from 1914–18 (non-standard)

I’ll be there between 9:30 and 11:30 (standard)

I’ll be there between 9:30–11:30 (non-standard)

Dashes as alternative speech marks

The CLOSED-UP EM DASH can act as an alternative to speech marks (or quotation marks) in dialogue in both UK English and US English.

Sylvain Neuvel uses this technique in Sleeping Giants and it works because the scenes in which it occurs take place in a secret location with an anonymous (even to the reader) agent running the interrogation. Each speaker’s turn is indicated with an em dash. The agent’s speech is rendered in bold.

—There is no need to get angry.

—I’m not angry.

—If you say so. You have a problem with authority.

—You don’t need a test to work that one out.

It can be an effective tool for fiction that’s dialogue driven – almost like a screenplay – but it gets messy when there are more than two speakers in a conversation, and becomes unworkable if you want to ground your dialogue in the environment with narrative (action beats, for example). And, of course, the dialogue needs to be standout because that’s all there is.

Dashes that indicate end-of-line interruptions

To indicate that a speaking character has been interrupted, use a CLOSED-UP EM DASH, whether you’re publishing in US or UK English.

Here’s an example from Mick Herron’s Dead Lions (p. 115)::

‘You got the guys—’

‘Yeah yeah. Catherine got the guys at the Troc to pick them up.’

And another from Linwood Barclay’s Parting Shot (p. 380):

“I know exactly who you are,” she said, and reached out and took his hand in hers.

Dashes for dialogue interrupted by narrative description

Dashes offer clarity when dialogue is broken by narrative description and the speaker hasn’t finished talking.

Here’s how it could be rendered in US English using CLOSED-UP EM DASHES:

And if you’re following UK English convention, use SPACED EN DASHES:

Notice how I’ve also used double quotation marks in the US version and singles for the UK one. Again, this isn’t about being right or obeying a rule; it’s a convention, and one that’s not always adhered to. Consistency is king.

Dashes that indicate faltering speech

If your character is out of breath, taken aback, caught off guard, frightened, or nervous, you might want to indicate faltering speech with punctuation.

There are no absolute rules about how you do this; it depends on the effect you want to achieve.

If you want to denote a staccato rhythm, HYPHENS are a good choice. This works for sharper faltering where the character stammers or stutters.

If the faltering related not to letters but to phrases, you could use a CLOSED-UP EM DASH (US style) or a SPACED EN DASH (UK style).

Ellipses are another option. They're not dashes but they're handy for faltered speech that has a pause in it. You can use these with your dash of choice.

"No. I-I-I mean, not really. It was an accident. I just s-s-saw him standing there and I flipped," Marion said.

Closed-up em dash for faltering phrasing (US style):

"I can't—I mean I shouldn't—well, it's difficult to know what to do."

Spaced en dash for faltering phrasing (UK style):

'I can't – I mean I shouldn't – well, it's difficult to know what to do.'

Ellipses for pauses (in conjunction with dashes):

'I can't – I mean I shouldn't – oh God ... you know what? It's d-d-difficult to know what to do.'

"No. I ... I mean, not really. It was an accident. I just s-s-saw him standing there and I flipped," Marion said.

Dashes as separators

HYPHENS are the tool of choice here. They’re short and sharp, and are perfect in fiction when you want to spell out words or numbers:

“That doesn’t make sense. The extension he gave me is 1-9-1-8. Are you sure it’s a five-digit number?”

Number separation comes in handy when you want to ensure your reader reads the numbers as distinct digits rather than inclusively. Compare 1918 (nineteen eighteen) with 1-9-1-8 (one, nine, one, eight).

Dashes that indicate connection, relation or an alternative

We use EN DASHES in place of to and and/or to show a connection between two words that can stand alone and that together are modifying a noun:

“Those two have had an on–off relationship for over a decade. I wish they’d make their minds up!”

‘I’m going to get the Liverpool–Belfast ferry. There’s one at ten thirty.’

Danny would take the money and Sheryl would get her promotion. It was a win–win.

I couldn’t see us winning the England–Brazil match but I put a tenner on us anyway. Just for fun.

Amir was an Asian–British scholar and something of a polyglot. ‘Languages float on the wind in my grandparents’ village,’ he once told me.

Dashes with adjectival compounds

Either EN DASHES or HYPHENS are used here, regardless of where you live.

When one adjective modifies another adjective, these words create a compound. If this compound is placed before a noun, it usually takes a HYPHEN for the purpose of clarity. When the compound comes after the noun and a linking verb, the hyphen can be omitted:

but

His shirt was navy blue.

“That well-read woman you were talking about? She’s called Sally.”

but

“Sally sure is well read, no doubt about it.”

Care should be taken, even in fiction, with regard to weighting. Let’s revisit the example of our polyglot Amir. Consider the differences between the following:

Amir was an Asian-British scholar and something of a polyglot. ‘Languages float on the wind in my grandparents’ village,’ he once told me.

Amir was an Asian British scholar and something of a polyglot. ‘Languages float on the wind in my grandparents’ village,’ he once told me.

Amir was a British Asian scholar and something of a polyglot. ‘Languages float on the wind in my grandparents’ village,’ he once told me.

In the first example, with an EN DASH, Amir’s Asianness and Britishness have equal weighting. In the second, with the HYPHEN, ‘Asian’ is modifying ‘British’ and carries less weight. In the third and fourth, where the dashes are omitted, the weighting is ambiguous.

The dash of choice (or its omission) can tell us something about Amir’s identity – how he, or the narrator, or the author perceives this – so it needs to be used purposefully.

Dashes indicating omission

You might want to omit words, fully or partially, because they’re profane, or to indicate that some of the letters are illegible, or to disguise a name.

There are several options for managing omission: em dashes, 2em dashes, en dashes and asterisks. Spacing comes into play. There are different conventions for US and UK style.

NHR recommends the following for UK style:

‘The scandal featured a certain Mrs H – – – – –. Can you believe it?’

‘I told you to p – – – off!’ he said, spittle flying.

‘I told you to p*** off!’ he said, spittle flying.

To indicate partial omission of a word with a single mark, choose the CLOSED-UP EM DASH:

‘The scandal featured a certain Mrs H—. Can you believe it?’

‘I told you to p— off!’ he said, spittle flying.

To indicate complete omission of a word with a single mark, choose the SPACED EM DASH:

‘The scandal featured a certain Mrs —. Can you believe it?’

‘I told you to — off!’ he said, spittle flying.

CMOS recommends the following for US style:

“The scandal featured a certain Mrs H⸺. Can you believe it?”

“I told you to p⸺ off!” he said, spittle flying.

To indicate complete omission of a word, choose the SPACED 2EM DASH:

“The scandal featured a certain Mrs ⸺. Can you believe it?”

“I told you to ⸺ off!” he said, spittle flying.

Summing up

Using dashes purposefully, and according to publishing convention, will bring clarity to your fiction writing. Think about your audience and what they’re used to seeing on the page, then choose your style and apply it consistently.

Consider, too, whether your choice of dash will amplify or reduce the significance (or weight) of your words when you’re using dashes as connectors or modifiers.

And if you’re still bamboozled, ask a pro editor. We know our dashes!

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

It’s one of these:

;

3 ways to use a semi-colon

There are 3 situations in which you’re likely to use a semi-colon in fiction:

- Parallelism: To separate two independent clauses that are related but equally weighted. In other words, one is not a consequence of or subordinate to the other.

- Clarity: To make a sentence that’s already subdivided by commas more readable. In this case, the semi-colon acts as a super-comma.

- Emojification: To create a winking emoji when placed before a closing round bracket. This might be useful if your fiction contains text messages. I’ve seen it done in YA fiction in the main.

Here, I focus on parallelism and clarity, but sentence pacing comes into play too – a useful addition to any fiction writer’s toolbox.

A little bit of grammar

Above, I mentioned independent clauses. An independent clause is a group of words that contains a subject and a predicate. In case you don’t know what they are – and many writers know how to write extremely well without knowing grammar terminology so there’s no shame in that – here’s an overview.

Subject

A subject is the thing in a sentence that’s doing something or being something. In the examples below, the subject is in bold.

- The FBI agent climbed out of the SUV.

- Detective Snooper was the bane of her life.

- “Doesn’t the pathologist in that TV show ever change her shirt?”

If you’re not sure what the subject of your sentence is, try this trick: change the subject into a question that you can answer yes/no to, as in the examples below.

|

Did the FBI agent climb out of the SUV?

|

Yes, he did. He (the FBI agent) is the subject.

|

|

Was Detective Snooper the bane of her life?

|

Yes, he was. He (Detective Snooper) is the subject.

|

|

“Doesn’t the pathologist in that TV show ever change her shirt?”

|

“No, she doesn’t. She (the pathologist in that TV show) is the subject.

|

A predicate is the part of a sentence that contains a verb and that tells us something about what the subject’s doing or what they are.

In the examples below, the predicate is in bold.

- The FBI agent climbed out of the SUV.

- Detective Snooper was the bane of her life.

- “Doesn’t the pathologist in that TV show ever change her shirt?”

If you’re not sure what the predicate is in a sentence that’s a question, turn it into a statement, as in the example below. The result might be clunky but it’ll show you what’s what. The subject is in bold and the predicate in italic.

|

“The pathologist in that TV show doesn’t ever change her shirt.”

|

Quick recap: an independent clause is a group of words that contains a subject and a predicate. The subject is in bold, the predicate is in italic, and the full independent clause is in red.

- The FBI agent climbed out of the SUV.

- Detective Snooper was the bane of her life.

- “Doesn’t the pathologist in that TV show ever change her shirt?”

Parallelism and the semi-colon

Take a look at these two independent clauses.

- The FBI agent fell to the ground.

- The gravel dug into her elbows.

The second sentence is related to the first because the gravel that’s digging into the agent’s elbows is what she experiences after falling to the ground. We can therefore use a semi-colon to indicate this relationship, if we wish.

- The FBI agent fell to the ground; the gravel dug into her elbows.

Note that the first word of the clause after the semi-colon does not take an initial capital letter.

Could we use a colon?

A colon is non-standard because colons introduce additional/qualifying information about the first clause, not new information. Think of the information they introduce as subordinate, if it helps.

I recommend avoiding colons to join parts of a sentence that are equally weighted.

|

Non-standard – new information (AVOID)

|

The FBI agent fell to the ground: the gravel dug into her elbows.

|

|

Standard – qualifying information

|

The FBI agent fell onto something sharp: gravel.

|

|

Standard – qualifying information

|

The FBI agent pulled out her gun: a Glock.

|

A comma is non-standard when joining two independent clauses. Sentences using commas in this way are said to contain comma splices.

I recommend avoiding this usage.

|

Non-standard with comma (AVOID)

|

The FBI agent fell to the ground, the gravel dug into her elbows.

|

|

Standard with semi-colon

|

The FBI agent fell to the ground; the gravel dug into her elbows.

|

|

Standard with full point

|

The FBI agent fell to the ground. The gravel dug into her elbows.

|

Heavily punctuated sentences can be confusing and clunky. For the reader, it can mean limping through your prose rather than moving at a pace dictated by narrative intent.

Take a look at this example from Mick Herron’s Dead Lions, p. 88. There are two semi-colons in the original version, but for this example I’m focusing only on the first (see the section in bold).

|

Original with semi-colon

He was bald, or mostly bald – a crop of white stubble gilded his ears – and gave off an air of pent-up energy, of emotions kept in check; the same sense Lamb had had watching the video of him, shot eighteen years ago, through a two-way mirror in one of Regent’s Park’s luxury suites. Joke. These were underground, and were where the Service’s more serious debriefings took place; those which it might later prove politic to deny had happened. |

He was bald, or mostly bald – a crop of white stubble gilded his ears – and gave off an air of pent-up energy, of emotions kept in check – the same sense Lamb had had watching the video of him, shot eighteen years ago, through a two-way mirror in one of Regent’s Park’s luxury suites. Joke. These were underground, and were where the Service’s more serious debriefings took place; those which it might later prove politic to deny had happened.

2. Amended with comma

He was bald, or mostly bald – a crop of white stubble gilded his ears – and gave off an air of pent-up energy, of emotions kept in check, the same sense Lamb had had watching the video of him, shot eighteen years ago, through a two-way mirror in one of Regent’s Park’s luxury suites. Joke. These were underground, and were where the Service’s more serious debriefings took place; those which it might later prove politic to deny had happened.

The en dash in the first alternative version looks awkward because we already have two parenthetical en dashes in play.

What happens if we introduce a comma instead? The sentence is already comma-heavy. All we’ve done is bring in yet another to muddy the waters.

The semi-colon works best. It effectively links the clauses it connects, but in a way that subdivides the sentence clearly.

However, pacing comes into place here too. There’s more on pacing below but, for now, compare the original and the version amended with a comma. The creepy voyeurism is starker when set off by the semi-colon.

More on pacing and the semi-colon

The semi-colon is harder than the comma. It lengthens the pause or increases the distance between two clauses that could have been linked with a comma, making them both stand out.

The semi-colon is softer than the full point. It shortens the pause or reduces the distance between two clauses that could have been linked with a full point, indicating a stronger, more intimate relationship.

Back to Herron for a closer look at the second semi-colon (see the section in bold) and some alternatives we could try:

He was bald, or mostly bald – a crop of white stubble gilded his ears – and gave off an air of pent-up energy, of emotions kept in check; the same sense Lamb had had watching the video of him, shot eighteen years ago, through a two-way mirror in one of Regent’s Park’s luxury suites. Joke. These were underground, and were where the Service’s more serious debriefings took place; those which it might later prove politic to deny had happened.

He was bald, or mostly bald – a crop of white stubble gilded his ears – and gave off an air of pent-up energy, of emotions kept in check; the same sense Lamb had had watching the video of him, shot eighteen years ago, through a two-way mirror in one of Regent’s Park’s luxury suites. Joke. These were underground, and were where the Service’s more serious debriefings took place, those which it might later prove politic to deny had happened.

In the original, the semi-colon acts as a super-comma, subdividing the whole sentence into two more readable chunks.

However, more marked is the impact on the pace. The semi-colon forces us to slow down. That’s important because the clause that comes after it is about the denial of interrogations. The semi-colon makes us pause a little longer, which makes the sinister information that follows stand out.

Semi-colons and dialogue

Some authors resist the use of semi-colons in dialogue, usually on the grounds that the reader can’t hear the punctuation. Does that mean you shouldn’t use them?

A novel’s dialogue isn’t real-life speech; it’s a representation of it. Speech, like narrative, has rhythm. The writer’s job is to create speech that’s clear and well paced. If a semi-colon helps you to do that, why wouldn’t you use it?

Here’s a great example from David Rosenfelt’s New Tricks, p. 316:

|

Original with semi-colon

“You can testify that you spoke to your father that night on Sykes’s phone, and you can say why you went to Mario’s. I can’t say those things in closing arguments; I can only talk about evidence already introduced.” Amended with full point “You can testify that you spoke to your father that night on Sykes’s phone, and you can say why you went to Mario’s. I can’t say those things in closing arguments. I can only talk about evidence already introduced.” |

Both versions work but Rosenfelt elects to use a semi-colon because he wants to show the relationship between the two independent clauses. A full point would pull the clauses a little further apart and reduce the intimacy between them.

Should you use semi-colons in your fiction?

Some authors prefer to omit semi-colons for a variety of reasons: they're deemed pretentious, confusing, interruptive or ugly. But I’m not sure we should judge them so harshly:

- They needn’t be pretentious. There’s nothing pompous about Herron and Rosenfelt’s writing. Both authors create compelling modern commercial fiction that keeps their readers on a page, and dying to turn it.

- While not all readers understand the grammatical nuances of the semi-colon, few will be stopped in their tracks if you use it well.

- Are they interruptive? Yes; if you use them too frequently; and your writing lurches; like a driver who’s too heavy on the brakes; too much of anything can grate. And; yes, if; you put them; in the wrong; place. Used purposefully, however, they can affect rhythm and bring clarity to a story.

- As for ugly, well, that’s subjective. I think they’re just lovely!

Further reading and cited works

- Dead Lions, Mick Herron, John Murray, 2013

- Dialogue tags

- How to punctuate dialogue

- How to use adverbs

- How to use apostrophes

- More resources for indie authors

- New Tricks, David Rosenfelt, Grand Central, 2009

- Style sheet template

- Using commas and conjunctions

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

The apostrophe is the same mark as a closing single quotation mark: ’ (unicode 2019).

This is worth remembering when you use them in your fiction to indicate the omission of letters at the beginning of a word. More on that further down.

What do apostrophes do?

Apostrophes have two main jobs:

1. To indicate possession

2. To indicate omission

And sometimes a third (though this is rarer and only applies to some expressions):

3. To indicate a plural

1. Indicating possession

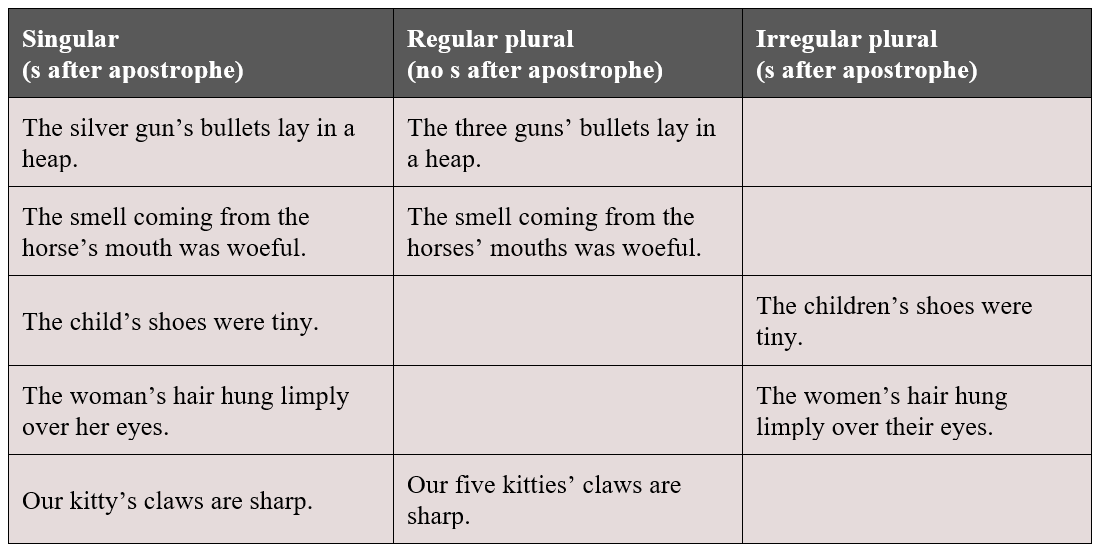

The English language doesn’t have one set of rules that apply universally. However, when it comes to possessive apostrophes, the following will usually apply:

Add an apostrophe after the thing that is doing the possessing.

- If there is one thing – one noun – an s follows the apostrophe.

- If there’s more than one noun, and the plural noun is formed by adding an s (e.g. 1 horse; 2 horses), no s is required after the apostrophe.

- If there’s more than one noun, and the plural is formed irregularly (e.g. 1 child; 2 children), an s follows the apostrophe.

Names can be tricky. The most common problem I see is authors struggling to place the apostrophe correctly when family names are being used in the possessive case, even more so when the name ends with an s.

Here are some examples of standard usage to show you how it’s done:

Hart’s Rules (4.2.1 Possession) has this advice: 'An apostrophe and s are generally used with personal names ending in an s, x, or z sound […] but an apostrophe alone may be used in cases where an additional s would cause difficulty in pronunciation, typically after longer names that are not accented on the last or penultimate syllable.’

If you're unsure whether to apply the final s in a case like this, use common sense. Read it aloud to see if you can wrap your tongue around it, and decide whether the meaning is clear. Then choose the version that works best and go for consistency across your file. Pedantry shouldn't trump prescriptivism in effective writing.

2. Indicating omission

Indicating omission when one word is created from two

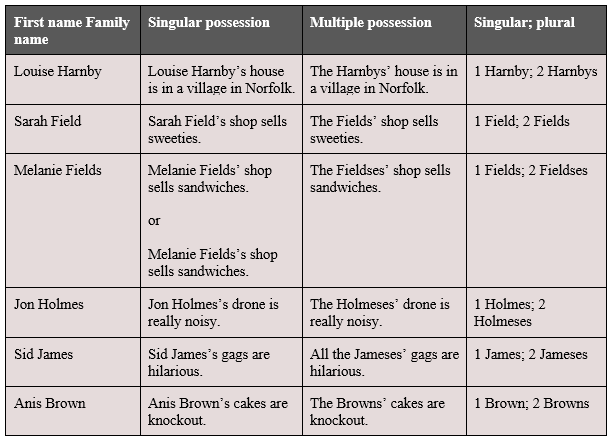

In fiction, we often use contracted forms of two words to create a more natural rhythm in the prose, particularly in dialogue. The apostrophes indicate that letters (and spaces) have been removed.

Common examples include:

We can use an apostrophe to indicate that a letter is missing at the end of a word (dancing – dancin’), the middle of a word (cannot – can’t) and the beginning of a word (horrible – ’orrible).

Start-of-word letter omissions are commonly used in fiction writing to indicate informal speech or a speaker’s accent.

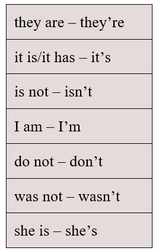

Make sure you use the correct mark. Microsoft Word automatically inserts an opening single quotation mark (‘) when you type it at the beginning of a word because it assumes you’re using it as a speech indicator.

Apostrophes are ALWAYS the closing single quotation mark (’) so do double check if you’re indicating omission at the start of a word.

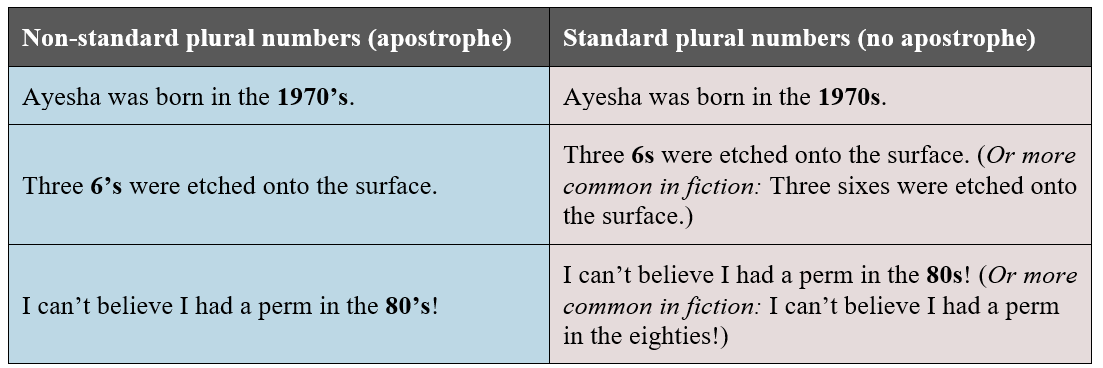

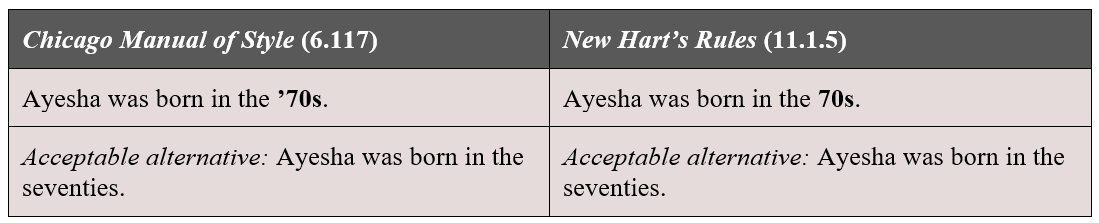

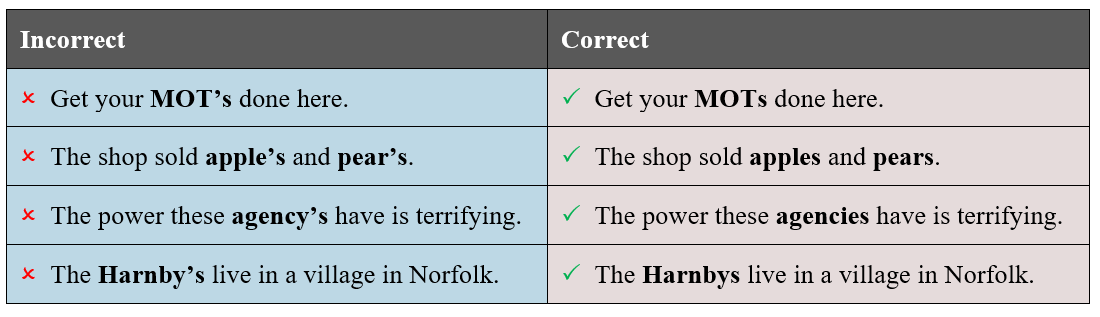

Plural numbers don’t usually require an apostrophe because there’s no ambiguity. In fiction writing, it’s common to spell out numbers for one hundred and below, but even when numerals are used, no apostrophe is needed for plurals.

In fiction, however, you can avoid the issue by spelling out the dates. This is universally acceptable, and my preference when writing and editing fiction.

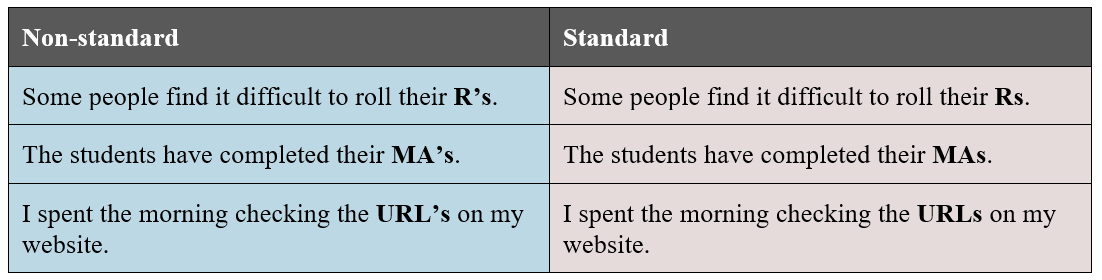

When indicating the plural of lower-case letters – for example, if you want to refer to two instances of the letter a – it’s essential to use an apostrophe because the addition of only an s will lead to confusion.

In the non-standard examples below, you can see how the plurals (in bold) form complete words, resulting in ambiguity.

When indicating the plural of upper-case letters, the apostrophe would be considered non-standard because there’s no ambiguity.

Possessive pronouns are the bane of the apostrophe novice’s writing life, especially its!

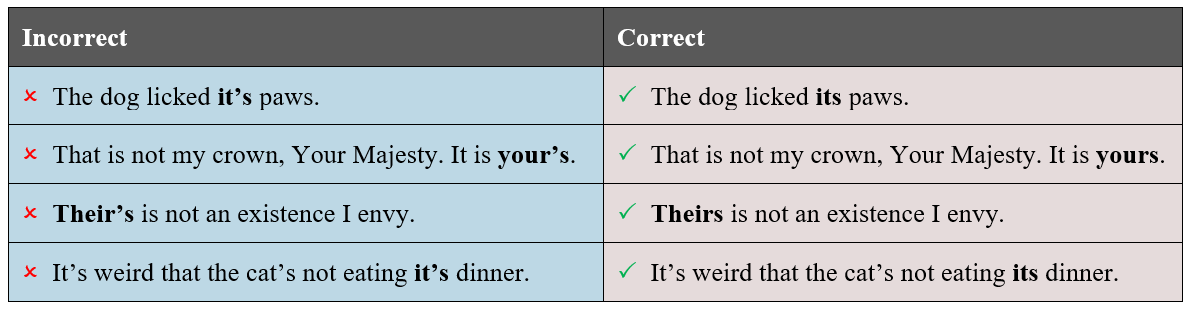

The following possessive pronouns NEVER need an apostrophe: hers, theirs, yours and its.