|

Round brackets, or parentheses, crop up less frequently than many punctuation symbols in fiction writing, but that doesn’t mean we must ban them. This post explores two ways to make them work effectively.

What are round brackets? This is what they look like: ( ) They always come in pairs, and act as alternatives to paired dashes or commas in fiction. They have other functions in non-fiction writing but I’ll leave that discussion to a non-fiction editor! Compare these examples:

All of the above are grammatically correct, though paired brackets (like dashes) are stronger than commas, and more interruptive to the eye than both commas and dashes, probably because they’re used less frequently and associated more with non-fiction work. Every writer will do well to ask themselves how their choice of parenthetical styling will affect the rhythm and clarity of their prose. Every writer will also do well to ask themselves whether readers will be annoyed by them. Like serial commas, adverbs and the singular they, round brackets rarely pass a reader or an editor without evoking opinion. More on that later. Brackets, full points and capitalization Regardless of which English you’re using – British or American, for example – the rule is the same:

Detective Harnby typed up the report and dumped it on the desk in the chief-super’s office (and what a sty that was).

Detective Harnby typed up the report and dumped it on the desk in the chief-super’s office. (And what a sty that was.)

Danger, Will Robinson! Round brackets in fiction garner strong opinion, usually negative. The most-cited reason I’ve seen – and it’s a valid one – is that they pull readers out of a story. Given that there’s no reason on earth why you’d want to pull a reader out of a story, tread carefully. Still, given that they’re not grammatically wrong, it’s only right that we should consider the ways in which round brackets might work in your fiction. The two I’ve seen most often are as follows:

Round brackets in fiction: Satire For an example of how round brackets can be used for satirical purposes, we need look no further than Dickens. In Our Mutual Friend (Wordsworth Editions, 1997), the viewpoint is omniscient. The scene is an ostentatious banquet hosted by the Veneerings. Dickens uses round brackets to set off narrative asides that poke fun at the guests and show them as the bumptious fools he believes them to be – and wants us to. Here’s an excerpt from p. 11:

A mirror reflects the Veneering crest, in gold and eke in silver, frosted and also thawed, a camel-of-all-work. The Heralds’ College found out a crusading ancestor for Veneering, who bore a camel on his shield (or might have done it if he had thought of it),

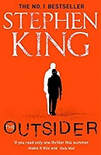

In other words, the crest is a farce. And one of the diners, a Mr Twemlow, is obsessed over whether he is Veneering’s ‘oldest friend’, though he would never admit to being bothered by such a thing. Dickens’s bracketed snipe (p. 12) leaves us in no doubt about the man’s snobbery; it interrupts the dialogue of Lady Tippins, a frightful show-off whose ‘my dear’ sends Twemlow into a tizzy: This approach is unlikely to find favour with readers who bought your high-octane thriller expecting a rollercoaster ride. The external narrator’s voice is overwhelming, and in most contemporary commercial fiction it will slow readers down, drag them out of the story, and infuriate them. Round brackets in fiction: Viewpoint shifts Take a look at this example from Stephen King’s The Outsider (p. 252; Hodder, 2018):

The brackets are effective here precisely because they’re interruptive. The narrative viewpoint in this section is third-person; we see the world as Holly, the private investigator, experiences it. Given that it’s third-person, our finding out something that Holly hasn’t considered shifts the narrative distance. Such a shift might jar under other circumstances because it yanks us out of Holly’s head. King, however, is a master of viewpoint, and he writes his characters with a rich immediacy. Still, he finds ways to introduce flexibility seamlessly, and in this case it’s with round brackets to introduce his omniscient narrator. The parentheses allow an external narrator to enter the story just for a moment – an all-seeing eye that tells us what Holly didn’t think – but that voice is cocooned safely within those round brackets, and is gone as soon as the reader’s eye passes over the closing symbol. King’s an experienced writer. If you’re not, I recommend holding a single character viewpoint and steering clear of bracketed interruptions from another narrator. Here are four ways we could recast the King excerpt:

Spaced en dash

With that taken care of, Holly went down to the hotel restaurant and ordered a light meal – no way was she paying room-service prices. Closed-up em dash With that taken care of, Holly went down to the hotel restaurant and ordered a light meal—no way was she paying room-service prices. Semicolon With that taken care of, Holly went down to the hotel restaurant and ordered a light meal; no way was she paying room-service prices. Full point With that taken care of, Holly went down to the hotel restaurant and ordered a light meal. No way was she paying room-service prices. Round brackets in fiction: Dialogue In Fix Your Damn Book! How to Painlessly Self-Edit Your Novels & Stories (Gift Horse Productions, 2016), James Osiris Baldwin advises never using round brackets in dialogue because they break ‘the fourth wall’. What’s the fourth wall? It’s originally a theatrical term but in our case refers to ‘The conceptual barrier between any fictional work and its viewers or readers’ (Lexico/Oxford Dictionaries). It’s good advice. It makes no sense to give an external narrator space inside a character’s speech. That’s why in the earlier Dickens example, the interruption comes between the speech-marked dialogue rather than within it. Summing up There’s nothing grammatically wrong with using round brackets. Stylistically, however, they could be a misfire. If you use them in your fiction, think care and rare: understand the impact they have on story and viewpoint, and use them infrequently.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

10 Comments

Louise Harnby

10/9/2019 11:04:15 am

Thank you, Felicia! Glad you enjoyed it!

Reply

Lindsey Russell

17/9/2019 03:36:05 pm

I hate round brackets in fiction - smacks of author intrusion. That doesn't mean I'd never use them - but I can't recall ever having the need to.

Reply

Louise Harnby

17/9/2019 04:31:22 pm

I think that's why I didn't mind when King did it in that example I quoted, because he was doing the intrusion purposefully. Still, he's King and what he can get away with it not necessarily what others can get away with!

Reply

Louise Harnby

17/9/2019 04:28:47 pm

Controversial ... yep, that about nails it!

Reply

Tedera

20/5/2020 10:46:44 pm

I have a gift and writing. Rather it's Fiction writing and Screenwriting, but I have to admit both fiction and screenwriting is very hard, I'm studying grammar and punctuation for my novel and parentheses is something I don't understand at all. Screenwriting is another thing I'm having difficulty with, but I will keep trying and not give up since I'm meant to be the writer God wants me to be.

Reply

El

11/8/2020 03:57:19 am

I hope you keep writing, Tedera! God bless!

Reply

Mary

15/12/2020 06:33:14 pm

Its my first time writing a book and I am getting confused as to when to use them and when not to use the brackets. I have been writing poetry my whole life. But its different when writing a book from my imagination.

Reply

El

11/8/2020 03:56:27 am

I've never found round brackets to be a disruption and I've never thought of them as taking me out of a story. Maybe I'm a very laid back reader? I don't know, but I've heard tons of complaints about them before and it has never bothered me. I generally see them used in more comedic/satirical ways, especially with a snarky narrator, and I've generally found the use of them to be somewhat funny in that context. I've seen parenthetical statements in NYT bestsellers and in self-published novels, and it has never once snatched me out of the story. But, like I said, I might be a more laid back reader and just unbothered by them in general. It isn't a huge deal to me.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed