|

Find out about 5 core character roles within a novel, and how the purpose they serve ensures the story stays focused.

|

|

Example from published fiction

Kate Hamer, The Girl in the Red Coat, Faber & Faber, 2015 (Kindle edition, Chapter 6) When I wake up in the morning everything's wonderful. For a moment I can't understand why. Then I remember: Mum's said if the weather's good we can go to the storytelling festival and that's today. |

Description beats

They help readers understand what characters are wearing, what they look like, what’s surrounding them, what they can hear, see, smell, touch or taste. That brings the scene alive.

|

Example from published fiction

Harlan Coben, Win, Arrow, 2021 (Kindle edition, Chapter 1) His name is Teddy Lyons. He is one of the too-many assistant coaches on the South State bench. He is six foot eight and beefy, a big slab of aw-shucks farm boy. Big T—that's what he likes to be called—is thirty-three years old, and this is his fourth college coaching job. From what I understand, he is a decent tactician but excels at recruiting talent. |

Dialogue beats

Like action beats, dialogue is an opportunity to bring depth to non-viewpoint characters in limited narrative styles. Their internal opinions and feelings – which we don’t have access to because we’re not in their heads – are revealed to us.

Why mixing up beats makes scenes more interesting

Writers and their publishing teams can use the drafting and editing stages to analyse the prose and evaluate whether there’s sufficient balance.

How to analyse a scene for beat balance

Approach 1

One way of approaching this is to think not in terms of the different types of beats but instead in terms of what they contribute, and whether there’s too much or too little.

And so writers and their editors can ask: Which of the following should the reader experience in this scene, and are they present? Here’s a summary of those elements:

- Sensibility (via emotion beats)

- Movement (via action beats)

- Breathing space (via inaction beats)

- Stability (via description beats)

- Expression (via dialogue beats)

An over-reliance on dialogue – even if it’s extremely well written – leaves a reader with no nudges about the emotions characters are experiencing or the environment they’re operating in. It’s two or more talking heads on a page.

If there should be expression in the scene, but the characters are chattering too much, think how you might turn the volume down, or at least disrupt it.

Consider introducing a few action, description and emotion beats. Or even turn some of the information contained within the speech into narrative.

An over-reliance on objective description – even if it gives the reader a rich sense of the environment – leaves readers with no way of accessing mood. It’s a menu of what’s where.

Description should stabilise the scene, not crush it so that it’s as flat as a pancake.

Help readers get under the skin of the characters and their environment by adding emotion or dialogue, or a little action that gives the scene some movement.

An over-reliance on emotion can be draining and doesn’t give the reader the chance to take a breath. It’s like a counselling session.

If there should be emotion, but a character’s self-absorption is swamping a reader’s ability to make sense of the environment, introduce description and action beats to ground the reader a little more objectively.

|

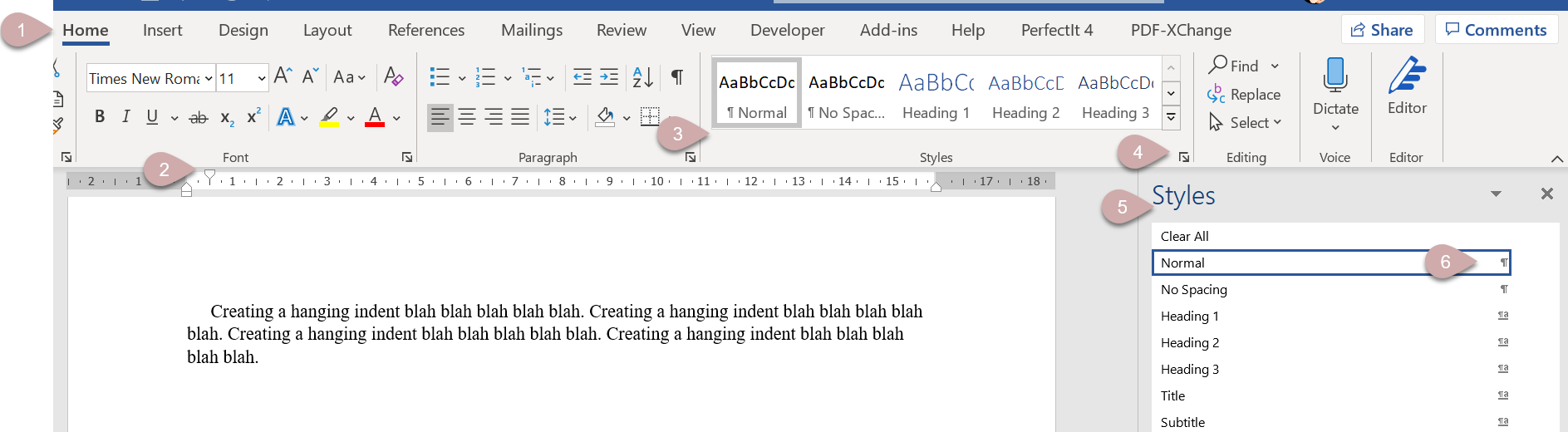

Approach 2

Another option is to colour-code the text in a scene according to what type of beats are in play. This can help authors and editors evaluate whether one type of beat is overbearing, and where they might add in additional types of beat to disrupt that dominance. It's a powerful way of communicating the problem visually and quickly. |

Summing up

Other resources you might like

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level: book

- Fiction editing line craft: books

- How to Line Edit for Suspense: multimedia course

- How to Write the Perfect Editorial Report: multimedia course

- Narrative Distance: multimedia course

- Resource library

- Switching to Fiction: multimedia course

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

In this post ...

- What a dialogue tag is

- Back-loaded tags

- Mid-loaded tags

- Front-loaded tags

- Impact level, psychic distancing and lyricism in front-loaded tags

What a dialogue tag is

- Are you enjoying reading that blog post?’ Louise said.

- ‘Are you enjoying reading that blog post?’ she asked.

In the above examples, the tags are shown in bold and comprise the subject (someone’s name or their pronoun) doing the speaking, and the verb from which the reader can infer that the action of speech is taking place.

Commonly used effective verbs include ‘said’, ‘asked’, ‘replied’, ‘whispered’, ‘muttered’, ‘yelled’, ‘continued’ and ‘added’.

Ineffective dialogue tags use verbs that bring to mind action that’s not related precisely to speech but to some other behaviour. Examples include ‘sneered’, ‘grimaced’, ‘laughed’, ‘harrumphed’, ‘huffed’, ‘sighed’, ‘snarled’ and ‘urged’.

Positioning tags in fiction:

Back-loading, mid-loading and front-loading

So where might they go?

Dialogue tags can be front-loaded, mid-loaded and back-loaded.

Back-loaded dialogue tags

Back-loaded tags come after the speech and are used commonly. Consider using them in the following circumstances:

- Length of dialogue: Your character’s dialogue is a short burst and you want to ensure the reader’s attention is focused on what’s being said straightaway, rather than who’s saying it.

- Impact level: The dialogue is relevant but low key. There’s no punchline that might be flattened by a tag.

EXAMPLES

Mid-loaded dialogue tags

Mid-loaded tags come between the speech. They, too, are a popular choice for writers. Consider this option in the following circumstances:

- Length: The dialogue stream is longer and you want to ensure your readers don’t wait too long to discover who’s speaking.

- Rhythm and context: You want to introduce a natural pause so that the speech doesn’t turn into a monologue. You can also supplement the tag with descriptive action that grounds the dialogue in the environment and helps the reader picture the scene.

- Impact level: You’ve written a witty, suspenseful or impactful punchline into the dialogue and don’t want it interrupted or flattened by a tag.

- Interrupted speech: You’ve written speech that’s interrupted abruptly and don’t want the tag interfering with the interrupter’s speech.

EXAMPLE 1

This first example is from David Rosenfeld's Collared.

Notice how in the above example of single-character dialogue, which comprises a total of 51 words, the impact point is with the closing sentence: ‘Sign the damn form and send it in’. Because the tag’s located earlier, that dialogue gets to shine.

Compare the original with this version, which I’ve given a back-loaded tag:

Back-loading the tag strips ‘Sign the damn form and send it in’ of its oomph.

EXAMPLE 2

Here’s an example from Linwood Barclay’s Parting Shot that shows how mid-loaded tags can protect the flow of interrupted dialogue.

Notice how by mid-loading the dialogue tag, Ms. Plimpton’s interruption – indicated by the closed-up em dash at the end of Duckworth’s speech – feels more authentic because it’s given the space to flow.

Front-loaded dialogue tags

Front-loaded tags come before the dialogue. This position is the one least used in most commercial fiction, and there’s a good reason for that: reader focus.

Those familiar with advice on writing for the web will know that web copy needs to be front-loaded with relevant keywords. This means that the important stuff comes first. That’s because visitors to websites are busy and scanning for solutions to their problems. When they don’t get them fast, they become frustrated and are more likely to jump to another site.

If the novelist’s done their job well, readers will invest way more time in soaking up their prose than if they were shopping for a new duvet cover. Even so, every word in a piece of fiction needs to count, and readers should still be focusing on the most important stuff.

And so if you’ve written great dialogue, most of the time you’ll want to ensure your readers are focusing on it as soon as possible. Front-loading the speech, rather than the tag, helps achieve that.

That’s not to say that front-loaded dialogue tags don’t have their place. They do, and they can be extremely effective when used purposefully.

When front-loaded tags work:

Impact level, psychic distancing and lyricism

Impact level

A front-loaded dialogue tag can function in the same way as a mid-loaded one when it comes to speech containing impact points. Again, we’re talking about dialogue that’s witty, suspenseful, or closes with an impactful line that you don’t want to flatten with a tag.

EXAMPLE

Let’s return to the excerpt from Collared. Although Rosenfelt uses a mid-loaded tag, he could have opted for a front-loaded one and preserved the oomph in his closing sentence. Here’s how it might look:

Psychic distancing

If you want the prose to feel more expository so that the reader is less closely connected to the character, front-loading the tag might be just the ticket. Doing this widens the psychic (or narrative) distance.

A tag tells of speaking whereas dialogue shows what’s being said. By placing the tag first, you draw the reader away from the character’s voice and give the prose a more objective feel.

EXAMPLE

This excerpt is from Jens Lapidus’s Life Deluxe.

|

They veered onto a side street off Storgatan.

Jorge's phone rang. Paola: "It's me. Que haces, hermano?" Jorge thought: Should I tell her the truth? "I'm in Södertälje." "At a bakery?" Paola: J-boy loved her. Still, he couldn't take it. He said, "Yeah, yeah, ‘course I'm at a bakery. But we gotta talk later—I got my hands full of muffins here." They hung up. |

Lapidus has front-loaded dialogue tags and thoughts in this excerpt, and it’s an excellent example of psychic distancing in action. The centring of the characters rather than the speech gives the prose a detached, clinical feel that shows rather than tells mood.

Jorge is a drug-dealer operating in Stockholm’s shady underworld. He’s only just out of jail but already he’s frustrated with a life of honesty. In fact, he’s got only one thing on his mind: easy money.

The wider psychic distance means we get to see the world through Jorge’s eyes but without getting too close to him. Perhaps Lapidus doesn’t want us to empathize with him too much. Instead, he widens the psychic distance just enough that we can make up our own minds about whether Jorge deserves the trouble coming his way.

Lyricism

Repeated use of front-loaded tags with short bursts of dialogue can introduce a lyricism into prose whereby the tags function as more than just indications of who’s speaking. They become part of the poetry.

This approach can work particularly well with parody, satire and comedic prose.

EXAMPLE

Mari said, ‘No.’

Ahmed said, ‘Yes.’

Sol said, ‘Maybe.’

Dave said, ‘I couldn’t give a shit. Is that the best you’ve got?’

Arthur said nothing, just yawned.

The bell rang. Suitably insulted, I raised the SIG, shot each student in the head, and retired to the staff room.

Notice how the multiple front-loaded dialogue tags are performing anaphorically. Anaphora is the purposeful repetition of words or phrases at the beginning of successive clauses.

It’s often used in poetry and speeches. When it’s used in novels, that repetition draws the reader's eye and can show rather than tell mood – boredom, monotony or, as in this case, disinterest. The tags are therefore key to the lyricism, and as important as the speech.

Summing up

The key is to consider what purpose your tag is serving and how it can best amplify the speech, evoke mood, and improve rhythm.

Cited sources

- Barclay, l., Parting Shot, Orion; 2017 (p. 380)

- Boyd, W., Solo: A James Bond Novel, Vintage, 2014 (p. 260)

- Crosby, SA, Blacktop Wasteland, Headline, 2021 (Chapter 1, Kindle edition)

- Lapidus, J, Life Deluxe, Pan, 2015 (Chapter 1, Kindle edition)

- Rosenfelt, D, Collared, Minotaur Books, 2017 (Kindle edition)

Fiction editing training: Books and courses

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level (book)

- Fiction editing and writing resources (online library)

- How to Line Edit for Suspense (multimedia course)

- How to Write the Perfect Fiction Editorial Report (multimedia course)

- Narrative Distance: A Toolbox for Writers and Editors (multimedia course)

- Preparing Your Book for Submission (multimedia course)

- Switching to Fiction (multimedia course)

- What is anaphora and how can you use it in fiction writing? (blog post)

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 96

- What's distinctive about editing crime fiction and thrillers

- What a good line editor needs to look out for

- What new entrants to the field need to study

- Marketing ideas

- Top tips for being a successful freelance editor/proofreader

- Do fiction editors use style guides?

Related resources

Join our Patreon community

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

In this post ...

- What a dialogue tag is

- Why tags should support, not supplant dialogue

- Tagging: Positioning the verb in relation to pronouns

- Tagging: Positioning the verb in relation to nouns

- Standing out in ways that serve reader expectations

What a dialogue tag is

- ‘Are you enjoying reading that blog post,’ Louise said.

- ‘I’m interested in learning about dialogue,’ ze replied.

- ‘Can I stick to non-fiction editing?’ he asked.

Effective dialogue tags use verbs from which the reader can infer that the action of speech is taking place. Examples include ‘said’, ‘asked’, ‘replied’, ‘whispered’, ‘muttered’, ‘yelled’, ‘continued’ and ‘added’.

Ineffective dialogue tags use verbs that bring to mind action that’s not related precisely to speech but to some other behaviour. Examples include ‘sneered’, ‘grimaced’, ‘laughed’, ‘harrumphed’, ‘huffed’, ‘sighed’, ‘snarled’ and ‘urged’.

In this post, I’m going to focus on a question that beginner fiction authors and editors often ask about: where to locate ‘said’ and other effective tagging verbs.

First, though, here’s a quick recap about why ‘said’ is such a popular dialogue tag.

Why tags should support, not supplant dialogue

It’s become so conventional that when authors go out of their way to replace every instance of ‘said’ with alternatives, they risk creating prose that feels laboured.

Showy speech tags in particular stand out, and that means they pull the reader’s attention away from the dialogue and push it towards the speech tag.

That’s not a good reader experience because when characters communicate through speech, that’s where the action is in that moment. The tag should support that action, not supplant it.

You can find out more about how to tag dialogue in Editing Fiction at Sentence Level, including:

- Showy speech tags and underdeveloped dialogue

- Showy speech tags and double-telling

- Non-speech-based dialogue tags and the reality flop

- Alternatives to showy speech tags – more on action beats

- Using proper nouns and pronouns in dialogue tags

- Omitting dialogue tags

Now let’s look at where to place ‘said’ and other tagging verbs.

Tagging: Positioning the verb in relation to pronouns

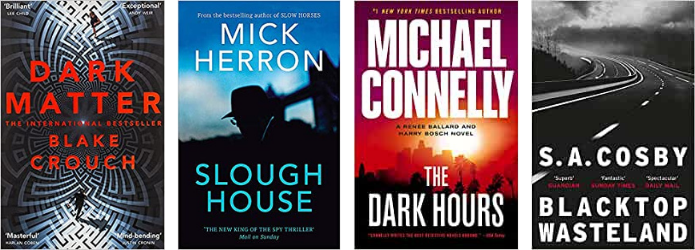

- “I know,” she says. “I’m violating the cardinal rule of family night.” (Crouch: Dark Matter)

- ‘I could do your job myself, if that’s what you mean,’ he’d said at last. (Herron: Slough House)

- “I don’t have no fucking mask,” he said. (Connelly: The Dark Hours)

- “Me and Jaymie will call it. You want your boy to go too?” he said. (Crosby: Blacktop Wasteland)

Let’s have a look at those examples when the verb is placed before the pronouns.

- “I know,” says she. “I’m violating the cardinal rule of family night.”

- ‘I could do your job myself, if that’s what you mean,’ said he at last.

- “I don’t have no fucking mask,” said he.

- “Me and Jaymie will call it. You want your boy to go too?” said he.

There’s actually nothing grammatically wrong with any of the edited examples, though I wasn't able to retain the past perfect in the second. What has gone awry is the narrative setting.

The dialogue is written in contemporary English but the verb placement evokes a distinctly historical feel that’s inappropriate.

So how about when nouns rather than pronouns are in play?

Tagging: Positioning the verb in relation to nouns

- “There was nothing you could have done,” Judith said. (Coben: Fool Me Once)

- ‘Are you feeling the cold?’ Danny asked. (McDermid: 1979)

- “Sir, I can’t help you until you get a mask,” Moore said. (Connelly: The Dark Hours)

- “The question is, do you have the balls to back it up?” Kelvin said. (Crosby: Blacktop Wasteland)

Now let’s move the verb so that it sits before the noun.

- “There was nothing you could have done,” said Judith.

- ‘Are you feeling the cold?’ asked Danny.

- “Sir, I can’t help you until you get a mask,” said Moore.

- “The question is, do you have the balls to back it up?” said Kelvin.

Again, there’s nothing grammatically problematic about this structure. Furthermore, the switch doesn’t jar in the same way as when the subjects are pronouns.

So how should independent authors (and the editors who support them) approach the structure of a tag?

Standing out in ways that serve reader expectations

- lots of potential buyers of their books have come to expect this construction

- and it's the approach that mainstream presses tend to take.

When readers are presented with stories that break with convention, there’s a risk that the story’s no longer the standout feature. Instead, those with strong preferences focus on minutiae that challenge their expectations.

That focus isn’t serving a writer who’s trying to build their author platform.

Mick Herron has built enough trust with his readership with his brilliant Jackson Lamb series that no one will bat an eyelid when they read the following in Slough House:

‘Ian Fleming,’ said Diana Taverner. ‘Means “Death to spies”.’

Nevertheless, I scoured the first chapter of that book and found that in the main he still favours placing the verb after the subject.

Summing up

However, it’s such a common convention that I recommend indie authors of contemporary commercial fiction follow it.

When the subjects in a tag are pronouns, this structure is essential for retaining a contemporary feel. When the subjects are nouns, placing them first gives the pedants one less thing to gripe about.

Related reading and training

- Coben, H., Fool Me Once, Arrow, 2016 (Chapter 1, Kindle edition)

- Connelly, M, The Dark Hours, Orion, 2021 (Chapter 1, Kindle edition)

- Crosby, SA, Blacktop Wasteland, Headline, 2021 (Chapter 1, Kindle edition)

- Crouch, B, Dark Matter, Pan, 2017 (Chapter 1, Kindle edition)

- Harnby, L, Editing Fiction at Sentence Level, Panx Press, 2020

- Herron, M, Slough House, John Murray, 2021 (Chapter 1, Kindle edition)

- McDermid, V, 1979, Little, Brown, 2021 (Chapter 1, Kindle edition)

Fiction editing training courses

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

What’s in this post ...

- What is narrative distance?

- Are narrative distance and psychic distance the same thing?

- How is narrative distance related to narrative style?

- Why writers and editors need to learn about narrative distance

- Using a visual framework to understand narrative distance

- Related resources for you to dig into

What is narrative distance?

A narrator is the person who tells the story. They can be a character in the book or an entity that stands outside it.

There can be multiple narrators in a book, too. That allows the author to present events from multiple perspectives.

‘Narrative distance’ describes the space between a novel’s narrator and the reader.

- If we, as readers, feel deeply connected to the narrator and their experience of the fictional world they inhabit, narrative distance is tiny.

- If we feel dislocated from them, more like we’re looking out on the story’s landscape objectively, the narrative distance is wide.

Are narrative distance and psychic distance the same thing?

You might find one or other useful depending on what issues you’re dealing with when you’re writing or editing. I like the word ‘narrative’ because it reminds me what part of the prose I’m dealing with.

Then again, I sometimes use the word ‘psychic’ because it reminds me that although I’m dealing with fiction, and therefore something that’s not real, the narrator within that creative realm still has their own lived experience and a raft of emotions that come with that.

How is narrative distance related to narrative style?

- First-person limited

- Third-person limited

- Third-person objective

- Third-person omniscient

Each of those narrative styles come with a certain degree of distance between the narrator and the reader.

For example, first-person narrations always feel a little more intimate because the pronoun ‘I’ is used. Second-person narrations can feel equally intimate, but in a voyeuristic way.

Third-person narrations – and the pronouns that come with them – are what we’re used to using for those not being directly addressed, so in prose they naturally put space between readers and narrators using the third person.

When we move beyond a framework of narrative style and start to think specifically in terms of narrative distance, we’re able to analyse the effectiveness of prose in a more nuanced and flexible way.

Why writers and editors need to learn about narrative distance

Perhaps you’ve never noticed before, and if that’s the case, the author and their editor have done a great job because the movement is seamless.

If that movement is jarring and too obvious, it could be an indication that narrative distance isn’t being controlled sufficiently. Editors and writers who can recognize narrative distance and evaluate its effectiveness are better equipped to solve the problem, and justify their solutions.

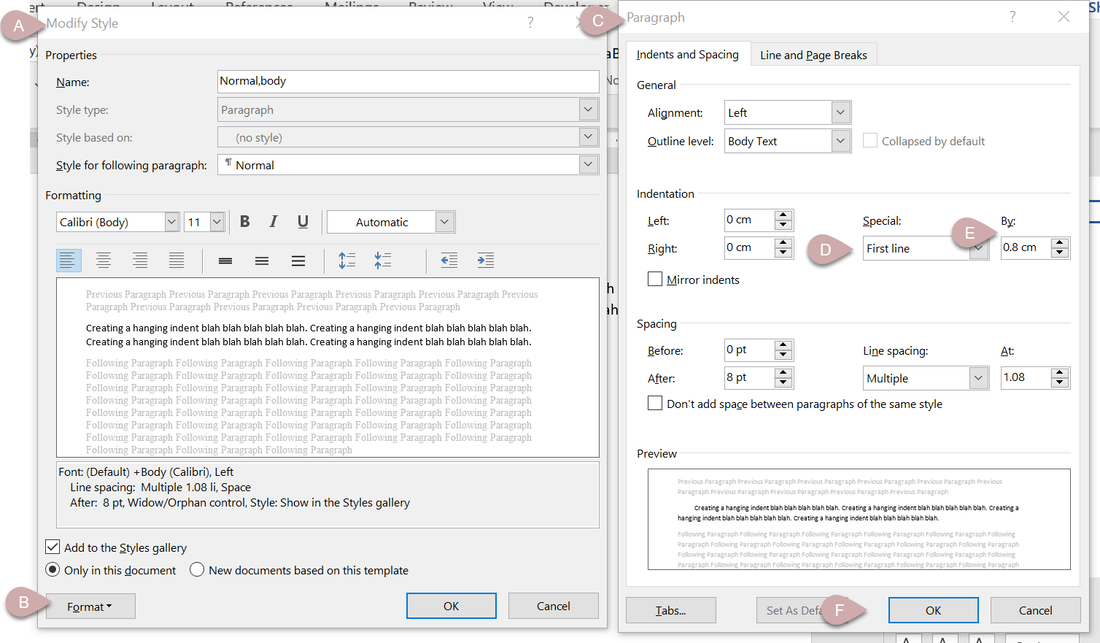

Using a visual framework to understand narrative distance

My solution was to structure my own learning as a visual framework. I presented that framework at the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading’s annual conference in September 2021 and then for the Society of Authors in October 2021.

The framework I shared at those two events garnered fabulous reviews and convinced me to record a webinar that everyone could access.

Narrative Distance: A Toolbox for Writers and Editors is available now to anyone who wants to lift the curtain on narrative distance and use it to craft prose that offers a better reader experience.

Use the button below to find out what’s included in the course.

|

If you’re a CIEP member, don’t forget that you can save 20% on all my courses. Log in to Promoted courses · Louise Harnby’s online courses. Then enter the coupon code at my checkout.

|

Related resources for you to dig into

- Blog post: 7 reasons why I’m not the right editor for you

- Blog post: How to avoid repeating ‘I’ in first-person writing

- Blog post: How to show the emotions of non-viewpoint characters

- Blog post: What’s the difference between a viewpoint character and a protagonist?

- Book: Editing Fiction at Sentence Level

- Book: Making Sense of Point of View

- Course: How to Write the Perfect Fiction Editorial Report

- Course: Switching to Fiction

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

This post looks at problematic language, the messages it might unintentionally convey, and how we can talk about the editorial conundrums we come across without judgement.

Embedding the language of preference in editorial discussion

- ‘What’s the correct way to punctuate this sentence?’

- ‘Is the grammar in this sentence right?’

- ‘What’s APA’s rule for hyphenating [...]?’

The problem with notions such as ‘right’, ‘correct’ and ‘rule’ is that they’re loaded. The implication is that there’s one way – a best way – to write and to edit.

In reality, there are multiple ways to punctuate a sentence, each of which could alter its flow and rhythm in nuanced ways.

There are multiple Englishes, too, each with grammatical and syntactical structures that vary from region to region within nations as well as from country to country.

And there are multiple style guides that express particular preferences.

All of which means there is no ‘correct’ way to punctuate a sentence, no ‘right’ grammar, and no ‘rule’ on hyphenation. What there are instead are conventions and choices that that can be implemented or ignored.

Instead, we could ask:

- ‘How can I punctuate this sentence to convey urgency? The author’s used commas but I’m wondering if spaced en dashes would be effective.’

- ‘Is the grammar in this sentence distracting or is the sense clear? The narrator is from [...] but I’m not.’

- ‘What’s APA’s preference for hyphenating [...]?’

The artistry of editing lies in helping the client craft prose in which the meaning is clear and interpreted as intended by readers. Embedding that principle – rather than the language of rights and rules – in the way we talk about our work means we’re more likely to think descriptively rather than prescriptively.

Whose standards and conventions are in play?

- How words are spelled in various Englishes

- How dialogue is punctuated

- Whether a term is hyphenated

- How apostrophes convey possession or omission

- Whether to place full points after contracted forms

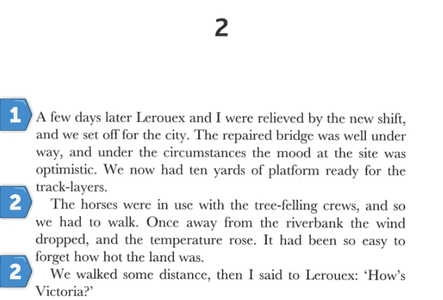

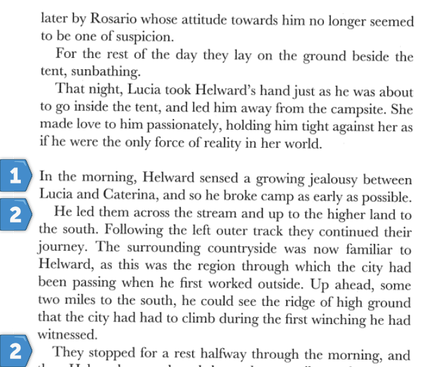

- Whether the first paragraph in a section is indented or not

- The grammatical structure of a sentence

- How verbs are conjugated

When we come across writing that doesn’t conform to these standards and conventions, some of us choose to refer instead to ‘non-standard’ language and ‘breaking from convention’ so as to avoid the judgement embodied in terms such as ‘right’, ‘best’, ‘correct’ and ‘rule’.

It’s been my preference because I felt it was more neutral and framed the issue around reader expectation rather than my own lived experience of language.

And that’s something I’ve been thinking about.

Why? Because these terms, too, need to be used with caution. We need to be aware that while standards and conventions help readers make sense of the written and spoken word, they are created and enforced by those with advantage, those who have the power to deem them as standard and conventional in the first place, and to assert their primacy.

That doesn’t make those standards and conventions better; it just means those who define them are in a position to do so. It also means that prose can be just as rich when those standards and conventions are ignored or flexed.

What about style guides?

Mindful editing means remembering that these preferences aren’t ‘right’ or ‘better’. They’re certainly not rules. Even Oxford’s New Hart’s Rules isn’t a rulebook! Rather, these are useful guides that help editors and authors bring clarity and consistency to writing.

However, editors – particularly those working on creative texts – need to be ready to bend when character and narrative voice would be damaged by prescriptive application of a style guide.

As for those of us working on texts that deal with identity and representation, we need to be ready to question the advice in a published style guide; it might be behind the curve.

Transferring judgement to the client

An author might not write in sentences that follow grammar, spelling and punctuation conventions, but that in no way means they’re a poor crafter of prose. Perhaps the way they lay down words is because they haven’t learned our conventions. Or perhaps they’ve actively chosen to ignore those conventions because that style of language doesn’t suit their character and narrative voices.

The mindful editor needs to recognize and respect both scenarios. Understanding which one is in play is critical because it will determine whether and which amendments are suggested, and why.

‘Wrong’, ‘non-standard’ or authentic voice?

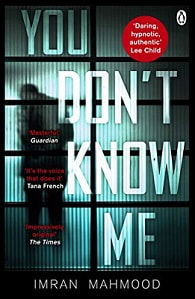

These excerpts are from the opening chapter of Imran Mahmood’s You Don’t Know Me (pp 4–5; Penguin, 2017).

[…]

He don’t know what I know. The problem for me was that although I know what I know, I don’t know what he knows. Do I let him speak to you in your language but telling only half the story, or do I do it myself and tell the full story with the risk that you won’t understand none of it?

Are the words I placed in bold ‘incorrect’ or ‘wrong’? That’s a judgemental approach that implies there’s a single perfect, right way to write and speak English. There isn’t.

Are the terms ‘non-standard’? To my ear, yes, some of them are, but that’s because I’m a 54-year-old middle-class white woman raised in Buckinghamshire, England, who was taught how to write and speak according to a standard dreamt up by … actually, I’m not sure who dreamt up the standard but it was probably someone who looked, spoke and was educated quite a lot like me and had the advantages I have.

Rather than thinking about these excerpts in terms of whether some of the words are non-standard or standard, instead we can evaluate them in terms of voice. Rich, evocative voice.

Our first-person narrator has been accused of murder and has elected to defend himself. As the blurb on the back cover says: ‘He now stands in the dock and wants to tell you the truth. He needs you to believe him. Will you?’

Actually, it’s his authentic voice that draws me – a 54-year-old middle-class white woman raised in Buckinghamshire, England – deep into his psyche so that I can see and hear him as if we are one. And that means I can root for him, invest in him, care about him, believe him.

Thinking about that narrative in terms of whether it’s ‘correct’ or ‘right’ would be butchery. To apply a digital red pen to it would be a crime.

And even those of us who might apply the term ‘non-standard’ to the emboldened words must acknowledge that such prescription is based purely on our own lived experience of English – how we write, how we speak, and what we were taught. That doesn’t make our way of speaking and writing better or worthier.

When story and characters drive language, readers will come along for the ride, regardless of their lived experience. When prescriptivism is behind the wheel, readers will disengage and find a different journey to take.

Framing errors in terms of author intention and reader expectation

Regardless, the focus here is on intention, and for that reason there are times when it’s appropriate for the editor to use the term ‘error’.

When editors are tasked with finding errors, they’re looking for what wasn’t intended in that particular project. Take a look at these four examples:

- “Are the autopsy results in yet?’ Milburn asked.

- Xe put xyr pen on the table and frowned. No way was he letting that one pass.

- She hears him clearly – banging on again about how their from out of town and don’t know their way around.

- ‘I wanted to call the police but Johnny ‘One Sock’ Swainston wasn’t having any of it.’

We can say without judgement that there are four ‘errors’ in the above examples because in each case the author likely made a mistake – they meant to use a consistent style of speech marks in the first example, meant the pronouns to be consistent in the second, meant to use ‘they’re' in the third, and meant to use an alternative style for the nested quotation marks in the fourth.

When we’re querying potential errors, however, we can still use the language of intention and reader expectation in our comments, thereby avoiding a more critical tone:

- Did you mean to write […] here or is this a typo?

- How about [...] instead? This would be less likely to distract the reader, who might be more used to seeing [...] and therefore misinterpret what you've written.

- The grammar in this section doesn’t align with your usual narrative voice, and reads more like something Character Y would say. Is this intentional? If not, how about trying [...]?

Summing up

- Saying something’s ‘right’ might imply that all alternatives are wrong when they aren’t.

- Defining something as a ‘rule’ might imply that breaking it is non-conformist, eccentric, non-compliant, even disobedient.

- Referring to something as ‘standard’ normalizes the preferences of those who have the power to make that decision in the first place.

Instead, we can frame our discussions and queries around meaning, author intention and reader experience. That way, we’re putting the prose where it belongs – front and centre.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 76

- What's special about romance editing

- The size of the market

- Tropes, challenges and styles in romance editing

- HEAs: Happy ever afters

- Romancelandia

- Understanding the romance writing and editing via Pride and Prejudice

- How to get in touch with Sarah Calfee

- Get a free sample of Sarah's book, How To Pride and Prejudice

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Listen to find out more about

- The main types of fiction editing and the kinds of things a fiction editor needs to look out for

- What additional training you might need

- The market and client expectations

- The need for a flexible hand

- Becoming a fiction editor (free booklet)

- Switching to Fiction (course)

Music credit

More fiction-skills resources

|

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Listen to find out more about

- What is style?

- The differences between rules, preferences and conventions

- Flexibility in fiction and non-fiction

- What is a style guide?

- Why style guides aren't rule books

- When editors need to respect tone, register, voice and brand identity

- What is a style sheet?

Music credit

More editorial-skills resources

|

Check out these additional resources that will help you develop your fiction-editing business.

|

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Why speech in a novel is different

Every line of dialogue should have a purpose. If it doesn’t, it probably shouldn’t be in your book.

It can take courage to remove words you've spent an age crafting but as I hope to show in the example below, readers don't need every little detail. Less is so often more!

A three-pronged approach to dialogue

When we focus on those three things, we avoid dull dialogue – conversations about the weather, how someone takes their tea or coffee, and courtesy statements such as ‘Hi, how are you?’

Voice tells us who characters are, what makes them tick – their fears, frustrations, hopes and dreams, identity, preferences.

Perhaps their speech is abrupt, rude, measured, polite, sweary or seductive.

When we change the way a character speaks, we change their voice. And that means we change them.

Characters can show us how they’re feeling via their dialogue.

Emotionally evocative speech allows readers to access the internal experience of a non-viewpoint character. And that makes it a powerful tool.

Perhaps their speech is abrupt, assertive, hesitant, forceful, pleading. Using the right words means the speech tags and narrative won’t need to be cluttered with further explanation.

Intention is another way of framing subtext. How characters speak tells us what they want.

Perhaps they’re asking questions for the purpose of discovery and understanding whodunit (doctors, lawyers, PIs and police officers regularly use dialogue in novels to this end). Dialogue can express a multitude of motivations.

Ask yourself what your character wants every time they open their mouth.

Example: Real but mundane dialogue

“Hi, Kevin,” I say.

“Hey, Andy. How you doin’?”

“Not too bad, thanks. Christ, it’s cold out though. I need something to warm me up. Gonna grab a coffee. Want one? Laurie, you?”

Kevin nods.

Laurie says, “Please. Milk and sugar.”

“So Kevin,” I say as I hand around the drinks, “we need to talk about Petrone.”

It’s the first chance I’ve had to tell Kevin about my meeting with the guy. I fill him in. When I get to the part where Petrone denied trying to have me killed, Kevin asks, “And you believed him?”

“I did.”

“Just because that’s what he said?”

I nod. “As stupid as it might sound, yes. I’ve had dealings with him before, and he’s always told me the truth, or nothing at all. And he had nothing to gain by lying.”

“Andy, the guy has had a lot of people murdered. How many confessions has he made?”

Were you enthralled by the welcome and refreshments section, or did you just wish we could get to the point? I think I know the answer!

The slimmed-down version

These meetings are basically of dubious value, since all we seem to do is list the things we don’t understand in our preparation for a trial we don’t know will even take place.

It’s the first chance I’ve had to tell Kevin about my meeting with Petrone. I fill him in. When I get to the part where Petrone denied trying to have me killed, Kevin asks, “And you believed him?”

“I did.”

“Just because that’s what he said?”

I nod. “As stupid as it might sound, yes. I’ve had dealings with him before, and he’s always told me the truth, or nothing at all. And he had nothing to gain by lying.”

“Andy, the guy has had a lot of people murdered. How many confessions has he made?”

What readers don’t care about

And so he leaves all of that out and lets the reader imagine that this stuff took place. And it’s enough. In the published novel, as opposed to the version I butchered, the first line of speech is “And you believed him.”

With that, we’re straight into Kevin’s incredulity and concern, and his desire to understand what the team is dealing with in regard to Petrone.

Meanwhile, Andy has his lawyer hat on. His initial reply is succinct, so that we are left in no doubt about his belief that Petrone was telling the truth, and that he is determined to reassure Kevin.

This is no-messing dialogue that focuses on story, not whether the speech is what we might actually hear – in its entirety – in real life.

It’s an excellent example of an author ensuring that every word counts and that there’s no bus-stop-talk filler.

Summing up

- Is every line relevant to the story?

- Is the character speaking with purpose or taking up ink/pixels on the page?

- Can mundane chitchat be removed without damaging sense and flow?

- Could the dull stuff be replaced with speech that deepens character?

Want the booklet version of this post? It's available on my Dialogue resources library. Click on the cover below to hop over to the page. Once you're there, choose the Booklets icon.

More fiction editing resources for authors and editors

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level

- Making Sense of ‘Show, Don’t Tell’

- Making Sense of Point of View

- Making Sense of Punctuation

- How to Write the Perfect Fiction Editorial Report

- Switching to Fiction

- The Differences Between Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Copyediting and Proofreading (free webinar)

- How to Punctuate Dialogue in a Novel (free webinar)

- Resource library: Dialogue and thoughts

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

FIND OUT MORE

> Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

> Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

> Learn: Books and courses

> Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Listen to find out more about

- What is sensitivity reading?

- What types of topics do people read for?

- What does the sensitivity reading process look like?

- Why should an author hire a sensitivity reader?

- What type of feedback does a sensitivity reader give?

- How does someone become a sensitivity reader?

- Some authors are hesitant to work with a sensitivity reader because there's concern about censorship or having books pulled. How do you address those concerns?

- Is sensitivity reading only useful for fiction?

- How do authors find sensitivity readers?

Discover more about Crystal at Rabbit with a Red Pen.

Mentioned in the show

- Find a sensitivity reader: Binders for Sensitivity Readers

- Conscious Style Guide

- Editors of Color

Music Credit

'Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Listen to find out more about

- Writing a series vs standalone novels

- Tips on developing a coherent series

- Starting afresh with a new set of characters in a new environment

- Top creative-writing tips for beginner author

- Recommended writing-craft resources

- Back-cover blurb and Amazon blurbs

- Cover design

Here's where you can find out more about Andy Maslen's thrillers.

Dig into these related resources

- Author resources

- Book: Editing Fiction at Sentence Level

- Blog post: 3 reasons to use free indirect speech in your crime fiction

- Blog post: Crime fiction subgenres: Where does your novel fit?

- Blog post: How to write dialogue that pops

- Blog post: Playing with sentence length in crime fiction. Is it time to trim the fat?

- Blog post: Writing a crime novel – should you plan or go with the flow?

- Podcast episodes: The indie author collection

Music Credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Listen to find out more about

- Doing your own narration vs hiring a pro

- How to find a professional voice artist

- Which qualities are important

- The process of working with a professional narrator

- Obstacles to creating audio books

- Costs and time frame

Here's where you can find out more about David Unger's books.

Dig into these related resources

- Author resources

- Book: Editing Fiction at Sentence Level

- The Editing Podcast: 6 ways to use audio for book promotion

- Booklet: How to narrate your own audio book

- Podcast episodes: The indie author collection

- Blog post: Why editors and proofreaders should be using audio

- Blog post: 5 ways to use audio for book marketing and reader engagement

- Blog post: How to go mobile with audio: Book-editor podcasting on the go

Music Credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Listen to find out more about

- What made David want to start writing and who inspired him

- Writing an alter ego

- The revision process

- On being edited

Here's where you can find out more about David Unger's books.

Dig into these related resources

- Author resources

- Book: Editing Fiction at Sentence Level

- Blog post: 3 reasons to use free indirect speech in your crime fiction

- Blog post: Crime fiction subgenres: Where does your novel fit?

- Blog post: How to write dialogue that pops

- Blog post: Playing with sentence length in crime fiction. Is it time to trim the fat?

- Blog post: Writing a crime novel – should you plan or go with the flow?

- Podcast episodes: The indie author collection

Music Credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Listen to find out more about

- What a zombie rule is

- Why split infinitives are not grammatically problematic

- Why it's okay to start a sentence with a conjunction

Dig into these related resources

- Blog post: Fiction grammar: Is it okay to start a sentence with ‘And’ or ‘But’?

- Blog post: What are expletives in the grammar of fiction?

- Blog post: Should I use a comma before coordinating conjunctions and independent clauses in fiction?

- Podcast: How to manage the grammar police

- Resources for proofreading your own writing

- Podcast: Linguist Rob Drummond on grammar pedantry, peevery and youth language

- Blog post: What's the difference between a rule and a preference? Advice for new writers

Music Credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Here's what two industry-recognized style guides have to say on the matter.

New Hart’s Rules (Oxford University Press): ‘You might have been taught that it’s not good English to start a sentence with a conjunction such as and or but. It’s not grammatically incorrect to do so, however, and many respected writers use conjunctions at the start of a sentence to create a dramatic or forceful effect.’

Chicago Manual of Style Online, 5.203 (Chicago University Press): ‘There is a widespread belief—one with no historical or grammatical foundation—that it is an error to begin a sentence with a conjunction such as and, but, or so. In fact, a substantial percentage (often as many as 10 percent) of the sentences in first-rate writing begin with conjunctions. It has been so for centuries, and even the most conservative grammarians have followed this practice.'

6 good reasons to start a sentence with ‘And’ or ‘But’

Great! We have the go-ahead from a couple of big hitters to use our two conjunctions at the beginning of a sentence. Now let’s dig a little deeper into why doing so can make fiction more effective. Here are my top six reasons:

- To serve natural speech

- To shorten narrative distance

- To introduce tension and suspense

- To add drama

- To emphasize the unexpected

- To make contrast explicit

Serving natural speech

When we speak in real life, conjunctions are often the first things out of our mouths. So it should be in novels that want to render speech authentically.

Fictional dialogue doesn’t replicate real-life speech completely – that would mean including a lot of boring stuff that one might hear at the bus stop. Rather, it’s a sort of hybrid that has the essence of reality but with the mundanity judiciously removed. It might sound like a cheat but readers thank authors who don’t bore them!

Small nudges towards reality help with the authenticity goal, which is where our conjunctions come in handy. Here are a few examples for you:

|

‘And you will have no hesitation in doing what has to be done? You have no doubts?’ (At Risk, Stella Rimington, p. 187)

‘And where’s he getting the money from? You know the situation as well as I do. He isn’t on leave of absence from a university.’ (The Dream Archipelago, Christopher Priest, p. 227) “But your way makes more sense. So you think Maura was working with Rex?” “I do.” “Doesn’t mean she didn’t set Rex up.” “Right.” “But if she wasn’t involved in the murder, where is she now?” (Don’t Let Go, Harlan Coben, p. 76) |

Shortening narrative distance

Dialogue gives us the character’s speech; narrative gives us the character’s experience. When that’s a first-person narrative, it’s easy to feel close to the narrator. With a third-person narration, the reader can feel separated from the character, as if they’re on the outside looking in.

Authors who want to reduce that space between the reader and the character – called narrative distance or psychic distance – can experiment with a narration style that sounds like natural speech even though it’s not dialogue.

Here’s a lovely example from Blake Crouch’s Recursion (p. 182).

|

There's a part of him that wants to run down there, charge through, and shoot every fucking person he sees inside that hotel, ending with the man who put him in the chair. Meghan’s brain broke because of him. She is dead because of him. Hotel Memory needs to end.

But that would most likely only get him killed. No, he'll call Gwen instead, propose an off-the-books, under-the-radar op with a handful of SWAT colleagues. If she insists, he'll take an affidavit to a judge. |

Notice how the narration style is third person, though it doesn’t feel like it. Instead, we’re right inside the viewpoint character’s head.

The position of the conjunction in this example isn’t the sole reason why the narrative distance feels short – the free indirect speech above and beneath plays a huge part – but it certainly helps to give us a sense of the character’s mentally working out a problem.

Introducing tension and suspense

Take a look at this excerpt from p. 21 of The Matlock Paper by Robert Ludlum.

|

Matlock walked to the small, rectangular window with the wire-enclosed glass. The police station was at the south end of the town of Carlyle, about a half a mile from the campus, the section of town considered industrialized. Still, there were trees along the streets. Carlyle was a very clean town, a neat town. The trees by the station house were pruned and shaped.

And Carlyle was also something else. |

With that one word – the conjunction – Ludlum stops us in our tracks. Yes, we’re thinking, the town’s neat, it’s clean. All well and good. But then we realize that there’s more to it, for beneath the pruned trees lies a dark underbelly.

The ‘And’, positioned right up front, forces us to pay attention to it. It’s not any old conjunction. Rather, it’s loaded with suspense that drives the reader to ask a question that isn’t explicitly answered: What else is that ‘something’?

Adding drama and modifying rhythm

In this excerpt from Parting Shot (p. 433), the author uses the conjunction at the beginning of the sentence to inject drama into a scene.

The new line makes the rhythm of the prose more staccato, but the ‘And’ at the beginning of the final line is what really packs a punch.

The viewpoint character, Cory, is a killer. He ponders almost matter-of-factly who the threats are, and reaches his conclusion as he closes in on the cabin.

|

Dolly Guntner certainly wasn't in a position to say anything bad about him.

Which left Carol Beakman. Carol had seen him. And while she didn't actually see him kill Dolly, if the police ever spoke with her, she'd be able to tell them it couldn't have been anyone else but him. As far as Cory could figure, the only living witness to his crimes was Carol Beakman. He was nearly back to the cabin. It seemed clear what he had to do. And he'd have to do it fast. |

If Linwood Barclay had omitted the conjunction, he’d have introduced a separation between two ideas: realizing what needs to be done, and when the killer is going to do it. Yet these two ideas are very much connected. The ‘And’ therefore fulfils its purpose as a conjunction – a joining word.

But there’s more. If he’d run the two ideas together with a conjunction between (‘It seemed clear what he had to do, and he'd have to do it fast.’), the line would have lost its wallop. The staccato rhythm (one that mirrors the cold calculation taking place in Cory’s head) is gone. Instead, the prose has flatlined; it seems almost mundane, like a stroll in the park rather than the planning of a murder.

However, the ‘And’ reinforces this extra information – the deed must be done fast. The emphasis adds drama to the line. The final line is still connected to the clause it’s related to, but the mood-rich rhythm, and the drama that comes with it, is intact.

Emphasizing the unexpected

An up-front ‘But’ is perfect for the author who want to emphasize the unexpected, surprise or absurdity. Take a look at this excerpt from Terry Pratchett’s Dodger (p. 170).

It’s true that omitting the ‘But’ would leave the meaning intact. However, adding the conjunction reinforces the Dodger’s emotional response to the boy’s suggestion – he’s taken by surprise because in times past, asking a peeler was exactly what he’d have done, without question, without fear.

And so that ‘But’ does more than act as a conjunction. With just three letters, we’re shown character mood.

Making contrast explicit and suspenseful

David Rosenfelt’s New Tricks (p. 92) includes a smashing example how the conjunction at the beginning of the sentence reinforces a contrast with what’s gone before.

|

I won't be able to place this in any kind of context until I go through everything Sam has brought, though he says he didn't see a reply to Jacoby's questions. Certainly the fact that a man who was soon to be a murder victim experimenting in any way with his own DNA is at least curious, and something for me to look into carefully if I stay on the case.

But a nurse comes in and asks me to quickly come to Laurie's room, so right now everything else is going to have to wait. |

That contrast is explicit because the ‘But’ acts as an interrupter. We’re deep in the POV character’s head regarding the murder victim, ruminating with our protagonist. The conjunction then shoves us out of that rumination. It’s not gentle; the ‘But’ is a big one – something’s up with Laurie.

Not that we know what. Rosenfelt doesn’t tell us yet. Instead, he makes us ask the question: Why? And with that question, just as with the Ludlum example above, we have suspense.

Summing up

Feel free to pepper your prose with sentences that begin with ‘And’ and ‘But’. Anyone who tells you you’re on shaky ground grammatically knows less about grammar than you do!

It’s likely that the myth around positioning these conjunctions came about in a bid to nudge people away from stringing together clauses and sentences with no thought to creativity. And while such an intention makes sense, we have to recognize that imposing this zombie rule on writing can actually destroy the magic of prose.

And on that note, I will sign off! (See what I did there?)

More fiction editing guidance

- 3 reasons to use free indirect speech

- Author resources library: Booklets, videos, podcasts and articles for authors

- Commas, conjunctions and rhythm

- Coordinating conjunctions

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level: My flagship line-editing book

- How to write suspenseful chapter endings

- Rules versus preferences

- Sentence length, pace and tension

- Switching to Fiction: Course for new fiction editors

- Transform Your Fiction guides: My fiction editing series for editors and authors

Cited sources

- At Risk, Stella Rimington, Arrow Books, 2004

- Don’t Let Go, Harlan Coben, Arrow Books, 2017

- Dodger, Terry Pratchett, Corgi, 2012

- Recursion, Blake Crouch, Pan Macmillan, 2019

- The Matlock Paper, Robert Ludlum, Orion, 2010

- The Dream Archipelago, Christopher Priest, Gollancz, 2009

- Parting Shot, Linwood Barclay, Orion, 2017

- New Tricks, David Rosenfelt, Grand Central Publishing, 2009

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Common examples are:

- there are/is/was/were

- it is/was

Take a look at the following pair. The first sentence is introduced by an expletive.

- There was a car parked outside the house.

- A car was parked outside the house.

When used well, expletives are enrichment tools that allow an author to play with a narrative voice’s register and the rhythm of sentences.

When prose is overloaded with them, it can feel cluttered with filler words that add nothing but ink on the page. At best, they widen the narrative distance between the reader and the POV character; at worst, they flatten a sentence and destroy suspense and tension.

Too much telling of what there is or was can rip the immediacy from a scene and encourage skimming. That’s a problem – it means the reader isn’t engaged and risks missing something.

Furthermore, if they’re not performing their rhythmic or emphasis role, expletives make sentence navigation more difficult because all they're doing is cluttering the prose.

Here's an example. Think I've overworked it? There are published books from mainstream presses with passages just like this made-up one.

It was a tiny room. There was a light switch with rust-coloured smudged fingermarks on the melamine surface. Was that blood? There was a noise coming from beyond on the back wall. It was a high-pitched whimper. Then there was silence. She held her breath and tiptoed forward.

Suddenly there was a scream.

The problem with the expletives in the passage above is that readers are bogged down in what there was rather than the viewpoint character's experience of discovery. Let's revise it to fix the problem.

The room was tiny. Rust-coloured fingermarks smudged the melamine surface of the light switch. Blood maybe. A noise came from beyond a door on the back wall. A high-pitched whimper. Then nothing. She held her breath and tiptoed forward.

A scream shattered the silence.

Notice how the narrative distance has been reduced in the revised passage. Now it's as if we're in the viewpoint character's head, moving with her second by second. We can focus on the room, the dried-blood fingermarks, the whimper, and the scream rather than the being of those things – their was-ness.

Removing the expletives and swapping in stronger verbs (smudged, shattered) enables us to tighten up the prose and introduce immediacy. And now there's no need for the told 'suddenly' – we experience the suddenness through the in-the-moment shattering.

As is always the case, obliterating expletives from a novel would be inappropriate because sometimes they're the perfect tool to help out with rhythm and emphasis.

The opening paragraph of Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities (p. 1) uses expletives galore, and masterfully at that. The repetition (anaphora) brings a steady rhythm to the passage that ensures the reader gives equal weight to the contrasting extremes – from best and worst to hope and despair.

The expletives introduce a detached sense of reportage that forces us forward rather than allowing us to dwell on any of the heavens or hells on offer. It’s simultaneously mundane and monstrous, and that's why it's magical.

And here’s an example from Dog Tags (p. 1) where omission of the expletive would rip the energy from the opening first line of the chapter and interfere with our understanding of which words we’re supposed to emphasize.

That was the USA Today headline on a piece that ran about me a couple of months ago.

Summing up

Grammatical expletives are a normal part of language and have every right to be in a novel. Overloading can destroy tension and make for a laboured narrative, but a purposeful peppering can amplify character emotion, moderate rhythm, and make space for the introduction of big themes in small spaces without sensory clutter.

Cited works and further reading

- Author resource library (includes links to free webinars)

- A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens, W. W. Norton & Company; Critical edition, 2020

- Dog Tags, David Rosenfelt, Grand Central Publishing, Reprint edition, 2011

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level: A Guide for Beginner and Developing Writers

- Making Sense of Punctuation: Transform Your Fiction 2

- ‘Playing with sentence length in crime fiction. Is it time to trim the fat?’

- ‘Playing with the rhythm of fiction: commas and conjunctions’

- 'Should I use a comma before coordinating conjunctions and independent clauses in fiction?'

- ‘What is anaphora and how can you use it in fiction writing?’

- 'Why "suddenly" can spoil your crime fiction'

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Point of view (POV) describes whose head we’re in when we read a book ... from whose perspective we discover what’s going on – and the smells, sounds, sights and emotions involved.

Third-person omniscient POV

This viewpoint is probably the trickiest to master. Omniscient means all-knowing. It’s the most flexible because it gives the reader potential access to every character’s external and internal experiences. It also has the potential to be the least intimate if not handled well.

Imagine a futuristic news helicopter. Inside, our roving reporter shifts her camera from one person to another, and one setting to another. She’s also got some serious kit, stuff that enables her to tap everyone’s phones, TVs and computers. But that’s not all; the characters’ brains are bugged too; our reporter knows what they’re thinking. She can see, hear and smell it all! Says Sophie Playle:

Examples: Deeper knowledge than third-person narration

If you’ve read anything by Neil Gaiman, you’ll see a blatant external narrator in evidence with a depth of knowledge that defies the rules of a third-person viewpoint. Here’s an example from Neverwhere (p. 10).

|

He continued, slowly, by a process of osmosis and white knowledge (which is like white noise, only more informative), to comprehend the city, a process which accelerated when he realized that the actual City of London itself was no bigger than a square mile [...]

Two thousand years before, London had been a little Celtic village on the north shore of the Thames which the Romans had encountered and settled in. London had grown, slowly, until, roughly a thousand years later, it met the tiny Royal City of Westminster [...] London grew into something huge and contradictory. It was a good place, and a fine city, but there is a price to be paid for all good places, and a price that all good places have to pay. After a while, Richard found himself taking London for granted. |

The first ten words might appear to be a third-person viewpoint (‘He’ refers to Richard, the protagonist), but that’s not the case. What follows is a distinct narrative other, a voice that explains ‘white knowledge’.

In the second and third paragraphs, the all-knowing narrator offers historical information. Then in the final paragraph, we’re told more about Richard. The viewpoint was never third-person objective. It was omniscient all along.

In Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, ‘the man’ takes centre stage in most of the sections such that we see what he sees and feel what he feels. It’s almost as if he’s the narrator, and once more we could be forgiven for thinking the viewpoint third person. But there’s more going on here.

In the following extracts, notice the shift beyond what it’s possible for the man to see, think or know.

|

He woke in the morning and turned over in the blanket and looked down the road through the trees the way they’d come in time to see the marchers four abreast. Dressed in clothing of every description, all wearing red scarves at their necks. Red or orange, as close to red as they could find. He put his hand on the boy’s head. Shh, he said. (pp. 95–6)

He wallowed into the ground and lay watching across his forearm. An army in tennis shoes, tramping. Carrying three-foot lengths of pipe with leather wrappings. [...] The phalanx following carried spears or lances tasselled with ribbons, the long blades hammered out of trucksprings in some crude forge upcountry. The boy lay with his face in his arms, terrified. (p. 96) |

In the first extract, only an all-knowing alternative narrator could be privy to the intent behind the marchers’ colour choice of scarves. In the second, the man watches the army, but it’s only an omniscient narrator who can know where their blades were forged and how the boy is feeling. Maybe that narrator is McCarthy; maybe it’s someone else. But it’s not the man.

Example: World-building backstory in a flash

Some genres – science fiction and fantasy for example – lend themselves well to omniscient narrators because they can provide critical world-building backstory quickly. Terry Pratchett’s Wyrd Sisters provides a fine example (pp. 1–2).

|

Through the fathomless deeps of space swims the star turtle Great A’Tuin, bearing on its back the four giant elephants who carry on their shoulders the mass of the Discworld. A tiny sun and moon spin around them, on a complicated orbit to induce seasons, so probably nowhere else in the multiverse is it sometimes necessary for an elephant to cock a leg to allow the sun to go past.

Exactly why this should be may never be known. Possibly, the Creator of the universe got bored with all the usual business of axial inclination, albedos and rotational velocities, and decided to have a bit of fun for once. |

What omniscient is not

An omniscient viewpoint can be powerful but it needs to be controlled and used with purpose. If we’re accessing one character’s thoughts and experiences, and we jump to another character’s viewpoint, it can jar the reader. That's called head-hopping.

Imagine you’re listening to your best friend tell you about a difficult experience. Even though it didn’t happen to you, her description of the event helps you to imagine the challenges she faced, the emotions she grappled with. You’re thoroughly immersed and emotionally connected.

Then someone else barges up to you both and tells you what it was like for them. Your friend butts back in to wrestle the telling back to her.

Would the interruption annoy and frustrate you? Would you feel like your efforts to invest in your friend’s story were being thwarted?

The impact is the same when it occurs in a book’s narrative (though not the dialogue, of course). That viewpoint ping pong is not omniscient POV. It’s third-person limited gone awry.

Recommendation

I recommend caution. The beauty of fiction often lies in the unveiling, in the immersion. Overuse of an omniscient narrator can block this.

The all-seeing eye can be a powerful tool – as demonstrated by the examples above – but less experienced authors, particularly those writing commercial fiction such as thrillers and mysteries, risk accidental head-hopping, which will destroy the tension and distance the reader from the characters.

Cited sources and related reading

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level, Louise Harnby, Panx Press, 2020

- Making Sense of Point of View (Transform Your Fiction series: 1), Louise Harnby, Panx Press, 2020

- Neverwhere, Neil Gaiman, William Morrow Paperbacks, reprint edition, 2016

- Resources for authors: Library of articles, podcasts, videos and booklets for independent writers

- The Road, Cormac McCarthy, Picador, 2009

- 'What’s the Difference Between Omniscient and Third Person Narration?' Sophie Playle, Liminal Pages

- 'What is head-hopping?'

- Wyrd Sisters, Terry Pratchett, Harper, reprint edition, 2013

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Dialogue tags, or speech tags, are complementary short phrases that tell the reader who’s talking. They’re not always necessary, particularly if there are only two speakers in a scene, but when they are used, this is what they look like:

- ‘Dump that corpse and don’t ever mention it again,’ the hooded guy whispered.

- “Thanks for holding the gun,” Tom said. “Now pull the trigger.”

- Marg turned. Smirked. Said, ‘Tomorrow. If you’re late, he’s late. Geddit?’

Said is often best because readers are so used to seeing it that it’s pretty much invisible and therefore less interruptive.

What’s the rule about where tags go?

Dialogue tags can be placed after, between or before dialogue. Authors sometimes ask which position is best or whether there’s a rule.

There is no rule. All three positions have advantages and disadvantages, depending on what you want to achieve.

Position: After dialogue

Readers are so used to seeing speech tags like said at the end of dialogue that they’re almost invisible. That allows the dialogue, rather than the speaking of the dialogue, to be the focus.

Below is a wee example from Recursion (p. 292). The speech takes centre stage; the doing of speech (screaming, in this case) comes afterwards.

Furthermore, when the tag comes after the dialogue, it can roll seamlessly into any supporting narrative, as shown in the example from The Ghost Fields (p. 194).

|

“Come on!” he screams.

‘It’s very … evocative,’ says Ruth. This is true. The brushwork may be crude, the planes out of perspective and the figures barely more than stick men, but there’s something about the work of the unknown airman that brings back the past more effectively than any documentary or reconstruction. |

There are a couple of potential disadvantages:

- In longer chunks of dialogue in scenes with more than two speakers, the reader will have to wait until the end of the speech to find out who’s saying what.

- Placement at the end of speech can flatten a one-liner or suspense point in dialogue.

Position: Between dialogue

Placing speech tags between dialogue is also common and unlikely to jar the reader. Here are three reasons why it works:

- The tag breaks up longer streams of dialogue, which is especially handy if a monologue’s rearing its head.

- We’re given an early indication who’s speaking. If there are more than two speakers in a scene, and the reader’s likely to be confused, placement between the speech is an effective solution.

- One-liners, suspense points and shocks get to take centre stage. Adding the speech tag at the end could flatten the tension.

Here are two examples in which the mid placement of the tag means the suspense isn't interfered with. The first is taken from The Ghost Fields (p. 194); the second is something I made up.

In the second example, rejig the sentence so that Tom said comes after all the speech, and notice how this makes the wallop vanish from the line about pulling the trigger.

Position: Before dialogue

Placement of the tag before the dialogue isn’t a no-no but it is a less common option and more noticeable.

A tag tells of speaking; dialogue shows character voice, mood and intention. When the speaker’s announced first, it’s a tap on the shoulder that draws attention to speaking being done. It expands what author and creative-writing expert Emma Darwin calls the ‘psychic distance’ between the reader and the speaker, which can flatten the mood.

And, yet, this can also be its advantage. That tap introduces a more staccato rhythm that can stop a reader in their tracks.

In this extract from Recursion (p. 292), the placement of the tag before the dialogue induces an acute sense of resignation – that dull thump in the pit of one’s stomach when the proverbial’s hit the fan.

Not placing tags: Omission