|

Are your readers bouncing from one character’s head to another in the same scene? You might be head-hopping. This article shows you how to spot it in your fiction writing, understand its impact, and fix it.

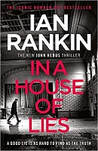

Rebus pushed open the wrought-iron gate. No sound from its hinges, the garden to either side of the flagstone path well tended. Two bins – one landfill, one garden waste – had already been placed on the pavement outside. None of the neighbours had got round to it yet. Rebus rang the doorbell and waited. The door was eventually opened by a man the same age as him, though he looked half a decade younger. Bill Rawlston had kept himself trim since retirement, and the eyes behind the half-moon spectacles retained their keen intelligence.

‘John Rebus,’ he said, a sombre look on his face as he studied Rebus from top to toe. ‘Have you heard?’ Rawlston’s mouth twitched. ‘Of course I have. But nobody’s saying it’s him yet.’ ‘Only a matter of time.’ ‘Aye, I suppose so.’ Rawlston gave a sigh and stepped back into the hall. ‘You better come in then. Tea or something that bit stronger?’ […] ‘Sugar?’ Rawlston asked. ‘I can’t remember.’ ‘Just milk, thanks.’ Not that Rebus was planning on drinking the tea; he was awash with the stuff after his trip to Leith. But the making of the drinks had given him time to size up Bill Rawlston. And Rawlston, too, he knew, would have been using the time to do some thinking. Anaylsis: Tight third-person limited narration Rebus is the viewpoint character. That means the internal experiences we access are limited to his. For example:

We cannot get in Rawlston’s head. All we can do is consider his internal experiences via his observable and audible behaviour, and his dialogue. For example:

What head-hopping would look like Here’s what that excerpt might look like if there was head-hopping going on:

Rebus pushed open the wrought-iron gate. No sound from its hinges, the garden to either side of the flagstone path well tended. Two bins – one landfill, one garden waste – had already been placed on the pavement outside. None of the neighbours had got round to it yet. Rebus rang the doorbell and waited.

Bill Rawlston walked down the hall and peered through the peephole. Rebus. Same age as him, though he looked half a decade older. He opened the door. Rawlston had kept himself trim since retirement, and the eyes behind the half-moon spectacles retained their keen intelligence. ‘John Rebus,’ he said, a knot forming in his stomach as he studied Rebus from top to toe. ‘Have you heard?’ The question riled him. Was Rebus stupid? ‘Of course I have. But nobody’s saying it’s him yet.’ ‘Only a matter of time.’ ‘Aye, I suppose so.’ Rawlston begrudged letting Rebus in but stepped back into the hall. ‘You better come in then. Tea or something that bit stronger?’ […] ‘Sugar?’ Rawlston asked. ‘I can’t remember.’ ‘Just milk, thanks.’ Not that Rebus was planning on drinking the tea; he was awash with the stuff after his trip to Leith. But the making of the drinks had given him time to size up Bill Rawlston. Rawlston had used the time to do some thinking, too. Rebus turning up here after all those years – it pissed him off. Analysis: Confused narration Notice how we bounce between the heads of Rebus and Rawlston. Now we have access to the internal experiences of both.

In that butchered version, the reader is forced to play a game of ping-pong on the page. Why head-hopping spoils fiction Here are 4 reasons to hold viewpoint rather than head-hopping:

1. Head-hopping renders a story less immersive

In Rankin’s original prose, we are limited to the world of the novel as Rebus experiences it. That’s powerful because every word on the page is a step we take with Rebus, as Rebus. I get to be a male, Scottish detective for a few hours rather than a female, English book editor! In my butchered version, I take that first step with Rebus but then trip and fall into Rawlston. Because I’m bouncing between those characters’ internal experiences, I don’t have time to invest in either. And so I stay as lil’ ol’ me. I do like being me, but when I buy one of Rankin’s books I want to immerse myself in its world for a few hours at a time and dig deep under the skin of the viewpoint character. I can be me without paying fifteen quid for the privilege!

2. Head-hopping diminishes suspense

In the original text, Rankin keeps the suspense tight by allowing us to access only Rebus’s senses. Rawlston’s sombre expression, twitching mouth and curt responses make Rebus (and us) think, Does he want me here? Does he begrudge my presence? What’s going on in his head? Those questions demand answers and we seek them in the clues offered by the limited narrative. Because the limited viewpoint requires Rebus and the reader to make assumptions based on what’s observable and audible, there’s uncertainty. That’s what provides the suspense, and it compels us to keep reading in the hope that the truth will be unveiled. In my head-hopping version, the prose is flat. There are no questions. We know what everyone’s thinking because we’re in everyone’s head. Readers aren’t called upon to use their imagination – both characters’ internal experiences are spoon-fed to us.

3. Head-hopping is less authentic

Head-hopping reminds readers that they are in a story written by an author. We don’t get to suspend belief because the writing won’t allow us to immerse ourselves that deeply. In Rankin’s original prose, we walk through the world as if we are Rebus, and Rebus alone. That’s what happens in real life. I know only what I’m thinking, feeling, seeing and hearing. I can’t be sure than another’s perception is the same. Audio-visual signals help me make reasonable assumptions but I’m only ever in my own head … or Rebus’s if I’m reading a story about him because Rankin knows how to hold viewpoint. In my mangled version of the excerpt, there’s a reality flop. Now I’m everyone, which is ridiculous of course. Authenticity has fallen off a cliff.

4. Head-hopping can be confusing

When a writer head-hops, the reader has to keep track of whose thoughts and emotions are being experienced. When a reader doesn’t know where they are in a novel for even a few seconds, that’s a literary misfire. This is what happens in the head-hopping excerpt. For example, Rawlston walks down the hall and identifies Rebus through the peephole. We’re right with him, in his head. But what follows is jarring. That he reports on his spectacles sitting in front of keenly intelligent eyes is oddly self-aware. Of course, it’s not Rawlston’s perception; it’s Rebus’s. And once we realize that, the prose makes sense. But working that out is not where Rankin wants the reader’s attention. He’s telling us a story and he wants us to read it. That’s why he holds a tight limited viewpoint throughout. Head-hop check Make a list of the characters in a chapter or scene. Identify the viewpoint character. There can be more than one viewpoint character in a book but most commercial fiction authors separate them by chapters or sections. Here’s a quick way to check whether you’re holding viewpoint. Viewpoint characters: What the reader can access

Non-viewpoint characters: What the reader can access

Some examples to show you the way

Summing up Even if your readers don’t know what head-hopping is, by removing it from your novel you’ll give them a more immersive, suspenseful and authentic journey through the world you’ve built. Plus, you’ll ensure they’re reading your story, not trying to work out who’s telling it.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with independent authors of commercial fiction, particularly crime, thriller and mystery writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

25 Comments

24/2/2020 05:48:35 pm

You wrote this for me, didn't you? Someone told you about me didn't they? LOLOL!

Reply

Louise Harnby

24/2/2020 06:02:57 pm

Ha! You always make me smile, Felicia! Glad you found it helpful. If there are other aspects of fiction writing you're struggling with at sentence level, let me know and I'll address them. I'm not a structural editor so not best placed to dole out advice on the bigger picture stuff but always happy to write blogs about line craft!

Reply

While I agree with your points, there's always an exception to any rule. I'll point to Elmore Leonard, who manages to hop from character to character within a scene without the reader even noticing. It's quite a trick but he pulls it off, giving the reader insight into different POVs that build tension. (And it's hard to say that his writing isn't immersive and suspenseful.) But - like many techniques - this one's best left to the masters.

Reply

Louise Harnby

25/2/2020 10:34:01 am

Absolutely agree about Elmore Leonard, though he isn’t writing in the third-person limited narration style that a lot of beginner novelists will use (and that Rankin uses in the example I gave). Leonard’s narrator is omniscient, though it’s not as strong or obvious as Neil Gaiman’s or Charles Dickens’s. It’s there though, in the same way that Cormac McCarthy’s is.

Reply

10/3/2020 09:48:02 am

Thank you for taking the time to thoroughly explain the pitfalls of head hopping, Louise...

Reply

Louise Harnby

10/3/2020 06:23:23 pm

Cheers, Anita! Glad you found it useful!

Reply

Lindsey Russel

12/3/2020 11:40:31 pm

I so want to ask a question here but but my dyslexic brain is struggling how to word it when I was accused by a friend of head hopping when all I'd done was describe one characters ACTIONS who wasn't the POV character.

Reply

Louise hArnby

13/3/2020 12:06:36 am

So showing a character’s physical actions (speech, movement .. stuff they do that’s audible and observable) is not headhopping. But actions that indicate internal experience would be. This sometimes happens with intention tells: e.g.she scowled in disgust. He moved to the left to make way for the officer. Those initial verbs are fine but the qualifying phrases are POV drops because they indicate internal motivations that we don’t have access to. Recasts might be: she scowled (leaving the reader to assume the disgust. Or the second example: he moved to the left and the officer pushed in front of him. Is it possible you were qualifying your non-POV characters’ actions with motivation or intention? Just an idea, if you want to email me with an example privately I can advise.

Reply

Lindsey Russell

13/3/2020 12:42:48 am

Thank you, Louise. I'm off to bed now - will sort something in the morning :)

Paul Sopko

29/9/2020 10:30:26 am

Hi Louise, Thank you very much for your expert advice. Yes I have done some 'head hopping' and now I can see how much better my novel will be in ways of keeping attention of the reader and helping the reader be more absorbed through out. I look forward to reading more of your tips. Thanks. Paul Sopko.

Reply

Louise Harnby

29/9/2020 02:34:34 pm

Thank you, Paul! Glad you found it useful!

Reply

Michelle Rosier

11/10/2020 02:03:39 pm

I am torn here. I am writing a historical romance and find head hopping a great vehicle to the emotions of the hero and heroine within scenes where they are working through their feelings. Can you pick this passage apart for me please? Maybe it isn't head hopping? I am confused as well as torn here :-)

Reply

Louise Harnby

11/10/2020 03:22:45 pm

It is head-hopping but it's your book, Michelle! If you want to write that way, and your readers enjoy it, you don't have to follow my guidance!

Reply

27/1/2021 08:06:51 pm

One of the best explanations EVER!!! I'm a new writer, writing my first novel, and I'm all over with POV. I just can't wrap my mind around it and I've read tons of articles. By far this post was the most helpful with clear explanations and examples..I'm new to your site but can already tell you are a great teacher!

Reply

Louise Harnby

30/1/2021 12:54:15 am

Thank you, Anna! That's wonderful to hear. There's a whole section dedicated to viewpoint on my Author Resources page if that's of interest: https://www.louiseharnbyproofreader.com/author-resources.html

Reply

Dallas Robertson

2/2/2021 06:45:17 pm

Hi Louise, completely agree this is the most clearly written article I’ve read on head hopping.

Reply

Louise Harnby

3/2/2021 12:02:28 pm

Hi, Dallas.

Reply

Louise Harnby

3/2/2021 05:50:25 pm

Should have that post ready by next week. I'll include some examples so you can see what I mean!

Dallas Robertson

3/2/2021 06:02:43 pm

Thanks, Louise, very helpful and articulate, as usual. It seems aiming for a consistent POV is best practise, but beyond that exactly how it’s used is very subjective.

Louise Harnby

3/2/2021 08:12:21 pm

I think you've misunderstood me. If your protagonist is unconscious, he's not the POV character. He can't be. He's not aware of anything so we can't see the world through his eyes any more than he can. He's out for the count.

Paul Adams

29/3/2021 07:24:41 pm

I am still confused. You can always have the POV person "imagine" or "sense" what is in the other person's mind. We do it all the time in life. As the POV person you can't express/state what is in the non-POV person's mind, but like real life you can guess if you are mere acquaintances or be near-certain if intimate. It is an approximation but it retains the POV and yet conveys necessary non-POV mental state that the reader is certainly interested in. It is immersive. And never confusing. Only I am.

Reply

Louise Harnby

30/3/2021 10:01:13 am

Yes, in real life you can guess what's on another's mind. And you do that by picking up the audible and visual clues. That's why I recommend novelists do the same: show the reader those clues so that they can do the guessing.

Reply

Alexei J Slater

22/5/2023 10:37:26 am

On this head-hopping issue, can I confirm the following - if your novel has several 'main characters' who the reader follows separately over chapters - in their heads so to speak - and then they finally meet at the denouement - if I understand the above correctly, you`re saying essentially that you have to pick one of these main character through which the chapter in question plays out and remain in his/her head only...

Reply

Louise Harnby

30/5/2023 02:31:47 pm

I see it as more nuanced in practice. It depends on how close the psychic distance is. If the narrative style is more objective, the perspective might be what multiple characters can experience through sound and vision. But if we're access all of their thoughts and feelings (we're inside their minds), than can be very difficult to pull off convincingly, particularly in commercial fiction.

Reply

Alexei J Slater

30/5/2023 02:36:02 pm

Hi Louise, Leave a Reply. |

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed