|

Exercising the right to accept or decline work is, in my opinion, one of the best things about owning one’s own business. And yet some editorial professionals feel guilty about saying no. What's to be done?

In Part 1, I looked at the reasons for accepting or declining work, how some editorial freelancers talk about feeling guilty, and how those statements stack up against the reality of what’s going on.

Here in Part II, I consider some simple ways of saying no that make it clear that the project is being declined, why this is so, and what the client can do to find an alternative supplier. I also explore the dangers of using an over-pricing strategy to deter an unwanted client, and consider how the guilt-ridden editorial pro might place her feelings within an adapted 10/10/10 framework in order to move forward with a decision that’s in her business's best interests.

Ways to say no

There’s nothing wrong with clearly and briefly stating your position to a client. Recall Sills, cited in Part I: Saying no isn't about negativity; it's about positivity (Sills, 2013). What's relevant is not the negative impact on the unwanted client, but rather the positive decision we take as business owners. The danger, especially with the desperate or emotionally charged client, is to get drawn into lengthy discussions, none of which are billable, about why you don’t want the work. Remember, you own your business, so it’s your choice. As several experienced colleagues have pointed out since I posted this article, honesty is often the best policy when giving your reasons for saying no, especially in the case of a client with whom you've had previous difficulties, because it enables them to learn from the experience, too. However, I do appreciate that for those who are prone to feelings of guilt, being honest about past problems can be so awkward as to cause even more stress. If it's the case that you would find being honest stressful, or you're worried about hurting your client’s feelings, you could choose an alternative stock answer to decline a project in a way that makes it clear that you’ve made your decision and the discussion is closed. Examples of stock answers for saying no might include:

Caution with the over-pricing approach

If you are contacted by a client with whom you don’t want to work because of reasons other than price, deterring them with an approach that you believe will price you out of their market can backfire horribly. This is because you don’t actually know what they are prepared to pay until they have accepted or declined your quotation. Let’s imagine the following fictional example:

I decide to price myself out of her market. I’d previously charged her £20 per hour for proofreading (which I accepted based on the bulk volume of the work). She’d negotiated me down from £23 per hour so I think I have a good sense of her top line. In order to deter her, I tell her that since we last worked together my rates have increased and I now charge £40 an hour – double the rate she paid seven months ago. To my horror, she accepts my quotation, telling me that I’m worth every penny. Now I’m stuck. It was never about the money for me; it was about the stress. The problem is that I didn't close the discussion – and having left the door open, she’s stepped through it. Now I have another decision to make: either I take on stressful work that I don’t want, or I have to go back and change my story, offering her a different reason: for example, that having checked my schedule, I can’t do the work after all but that I can point her in the direction of a good directory from where she can secure an alternative proofreader. This response implies that I didn't check my schedule properly in the first place, which is neither professional nor believable. I should have used the scheduling reason in the first place. Instead, I’ve wasted my time and my client’s time. I may not want to work with her but that doesn’t mean I shouldn’t respect that her time is precious too. I've also unnecessarily extended the correspondence.

Placing guilt in a 10/10/10 framework

If you’re the kind of person who struggles to say no to clients, try looking at it through a different lens. Business writer Suzy Welch’s 10/10/10 model (cited in Heath and Heath, 2013) asks us to consider how a difficult decision will make us feel in 10 minutes, 10 months and 10 years. In the case of editorial work, I think the time frames could do with being tweaked a little but the principle stands. Imagine you were to say no to one of the clients discussed in Part I (the strapped-for-cash client, the time-poor, emotional client, the manipulative client, or the inexperienced client).

If you’ve a tendency to feel guilty about declining work, you’ll probably still feel guilty 10 minutes later. In 10 hours you’ll probably feel relief that you stuck to your guns and kept your business schedule open for the kind of work that you need/want to take. And what about in 10 weeks? It’s likely that you’ll have completely forgotten the correspondence altogether.

Summing up

If you're encumbered with feelings of guilt when declining work, here’s a summary of tips to help you say no with confidence:

Let’s end with another quotation from Sills (2013): “Wielded wisely, No is an instrument of integrity and a shield against exploitation. It often takes courage to say. It is hard to receive. But setting limits sets us free.” We are the owners of editorial businesses. We set our own limits. We accept or decline work on terms that suit us, and are free to do so without drama, fear or guilt. This is nothing but normal business practice. Further reading Broomfield, Liz (2013). When should I say no? (Libro Editing) Heath, Chip, and Heath, Dan (2013). The 10/10/10 Rule for Tough Decisions (FastCompany.com) Sills, Judith (2013). The Power of No (Psychology Today)

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

2 Comments

Exercising the right to accept or decline work is, in my opinion, one of the best things about owning one’s own business. And yet some editorial professionals feel guilty about saying no. What's to be done?

Some of us have experienced a situation where we have to withdraw from an ongoing project because of what one of my colleagues calls “scope creep”.

Here, the originally agreed terms of the work have been breached by the client, rendering continuation of the project non-viable unless new terms can be negotiated that are acceptable to both parties. This demonstrates why it’s important to clarify the parameters of any editorial project before an agreement is made to carry out the work. How to pull out of existing project work is beyond the scope of this article. Here I’m focusing on saying no to the offer of editorial work prior to commencement of the project, and how guilt should not be part of the editorial business-owner’s decision to so. In Part I, I look at the reasons for accepting or declining work, how some editorial freelancers talk about feeling guilty, and how those statements stack up against the reality of what’s going on. In Part II, I’ll consider some simple ways of saying no that make it clear that the project is being declined, why this decision is being made, and what the client can do to find an alternative supplier. I’ll also explore the dangers of using an over-pricing strategy to deter an unwanted client, and consider how the guilt-ridden editorial pro might place her feelings within an adapted 10/10/10 framework in order to move forward with a decision that’s in her business's best interests.

Reasons to accept and reasons to decline

I might decline a proofreading project for one, or several, of the following reasons:

I might accept a proofreading project for one, or several, of the following reasons:

See also Liz Broomfield’s (2013) discussion of what kinds of work you might say no to at various stages of your business’s development.

It’s my business and my choice

Whether I accept or decline, the choice is mine. I’m not bound to carry out proofreading work that, for whatever reason, I don’t wish to. There’s no boss telling me that our company is contractually bound to do A or B, or that I must work for X, even though I find dealing with X stressful, intimidating, infuriating, or upsetting. I choose the hours I need/wish to work. I choose the type of editorial work I carry out (in my case, proofreading). I choose the material I feel comfortable with. I decide whether a fee is acceptable based on my needs and wants. Ultimately, I can decline a project for no other reason than I simply don’t fancy doing it. End of story.

Feeling guilty

Despite having control over the choices they can make, it’s not uncommon to hear editorial freelancers say they feel guilty about not accepting a job:

In all of the above, the story is of the problems being faced by the client if the editorial pro turns down the work. However, we as business owners need to flip things around and look at the situation from our own point of view.

The reality ...

Now let's look at the above 4 scenarios from the perspective of the editorial business owner:

No isn't negative ...

Psychologist Judith Sills (2013) argues that “No – a metal grate that slams shut the window between one's self and the influence of others – is rarely celebrated. It's a hidden power because it is both easily misunderstood and difficult to engage” and “it is easily confused with negativity”. So, when we decline work, we need think of the decision not in terms of negative impact on our clients, but rather in terms of the positive impact on our editorial businesses. In Part 2, we’ll look at ways to communicate an uncomplicated “no” message, and consider an adapted version of Suzy Welch’s 10/10/10 framework that should help the guilt-ridden editorial pro to say no with greater confidence.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Do we still need to learn how to use traditional proof-correction symbols given that most proofreading work is done onscreen these days?

My answer is an emphatic “Yes, you should learn them!”

As I'll show below, knowing how to use them will increase your efficiency, productivity, clarity, marketability, and professionalism. Traditional proofreading: Checking typeset proofs Many proofreaders work directly in Word, making actual changes to the text. In my experience, it's primarily self-publishing authors, academics, students and businesses that commission such direct intervention; almost all of my publishers want me to use the proof-correction symbols. That’s because I’m not editing the text; rather, I’m annotating pages that have been professionally designed – the pages appear as I would expect to see them if I walked into a bookshop and pulled the published book from a shelf. In this situation, I'm not just looking for spelling and grammar mistakes. I also need to annotate for problems with layout, for example:

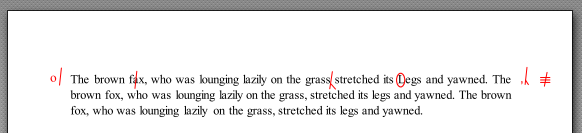

So, if you plan to work on page proofs that have been professionally typeset prior to publication, and you hope to acquire this work from mainstream publishing houses, you will need to know how to annotate the pages correctly with these symbols, even if you are proofreading onscreen. What do the marks look like? It depends where you live. If you need guidance about proof-correction marks in your particular region, contact your national editorial society. In some countries, the UK’s BSI marks are accepted for proofreading and copy-editing practice. In the UK, there is a single set of industry-recognized symbols. These have been prepared by the British Standards Institution (BSI) and are entitled “Marks for copy preparation and proof correction”. Over time they’ve been updated. The current marks are identified as follows: BS 5261C:2005. If you’re working for Canadian or US clients, read Adrienne Montgomerie’s article, “The Secret Code of Proofreaders” (Copyediting.com, 2014). As she points out, the Canadian Translation Bureau’s Canadian Style guide marks are quite different from the marks preferred by the Chicago Manual of Style. Why are proof-correction marks useful? When we proofread typeset page proofs, there’s little room to indicate what we want to change. Recall that each page we’re working on appears almost as it would if the printed book had been published. Using industry-standard proof-correction marks is an efficient way to annotate the page with the desired corrections. The symbols are a short-cut code of instructions that tell the designer exactly what to do. Once you’ve learned all the symbols by heart, they’re much quicker to use than long-hand text and take up minimal space. Open the nearest book you have to hand and look at how much white space there isn’t between the text and the margin – it’s not uncommon for me to work on page proofs with a 2cm margin either side of the text. Notice, too, how small the space is above and below a single line of text. The book has been designed and there's little room to annotate. Now imagine that in a given line there is a missing comma, a spelling mistake, and a word that needs decapitalizing. The example below illustrates how these problems would be marked up using the BSI proof-correction symbols. The long-hand alternative might be something on the lines of <Change “fax” to “fox”> in the left-hand margin, and <Insert comma after “grass” and decapitalize “Legs”> in the right-hand margin. Given that we only have 2cm margins to play with, that each line is spaced closely to its neighbours above and below, and that in a real set of proofs there may be several corrections in multiple lines, any instructions to the typesetter are likely to become cluttered and confusing. Proof-correction symbols solve the problem.

The use of proof-correction symbols therefore offers increased efficiency, productivity, and clarity. And if you’re a proofreader-to-be who wants to ensure you’re marketable to as wide a range of clients as possible, acquiring the ability to use this mark-up process is a no-brainer.

Attending to professional standards In addition to enabling you to work efficiently, productively, and clearly, and maximizing your marketability, there is also the issue of professionalism. Membership of a professional editorial society often requires knowledge of the relevant nationally approved mark-up symbols as a standard of good practice.

Where to find the UK marks The BSI provides a laminated 8-page summary sheet of all the marks you need to know for proofreading. Also included are short notes that enable the proofreader or copy-editor to identify the correct mark for both marginal and in-text mark-up, colour of ink to be used, and positioning of the symbols. The CIEP has an arrangement with the BSI whereby members can purchase the sheet for a reduced price. How to learn to use the marks Any comprehensive proofreading course worth its salt should test your ability to use the marks according to industry standards. It's not just about using the right mark so that the instruction is unambiguous, but also about knowing when to use the mark and when to leave well enough alone. In the UK, the CIEP and The Publishing Training Centre are examples of organizations offering industry-recognized courses that attend to these issues. If you live outside the UK, ask your national editorial society for guidance. Further reading If you’re considering embarking on a professional proofreading career, you might find the following related articles of use:

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses. |

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed