|

Are your thriller’s sentences front-loaded with filter words? If so, you could be slowing your reader down. This post explains what filter words are, how they affect a sentence and how to decide whether to include them or ditch them.

|

|

Under normal circumstances he would never put his hands on a lady. However, these were not normal circumstances. Not by a long shot.

Ronnie struck the manager just above her right eye with the butt of the .38. A divot the width of a popsicle stick appeared above her eye. Blood spewed from the wound like water from a broken faucet. |

The filter words have gone, and with them the unintended pathological introspection, but the momentum is restored. We're in the moment with Ronnie as he lashes out. It's no less violent but the pace of the prose now mirrors the action authentically.

When filter words make space for reflection

Let’s take a look at another example from Cosby’s Razorblade Tears, this one also from Chapter 2.

The filter phrase is ‘looked at’, and it’s important. Ike is looking hard at what’s in front of him. As will be revealed later, this girl is his murdered son’s daughter. Ike recalls something he’d said to his son a few months earlier: ‘But that little girl, she gonna have it hard enough already. She's half Black. Her mama was somebody you paid to carry her, and she got two gay daddies. So now what?’

Ike and his wife will now be raising the little girl. Cosby wants to focus our attention inward for a moment on Ike’s reflection, and the filter word makes space for that.

While filter words can be effective when they’re used to create a sense of introspection, littering prose with them will be disruptive and pull the reader out of the viewpoint character's headspace. In other words, the psychic or narrative distance will be widened and we’ll feel disconnected from the immediacy of the character’s experience.

For that reason, always use filter words judiciously. In the above example, Cosby offers just a single nudge, and it’s enough.

Summing up

- When filter words front-load a sentence, they’re the first thing a reader notices.

- They destroy momentum and so are often best avoided in pacy action scenes, regardless of their position.

- And even if they do serve a purpose – focusing a reader’s attention inwards on how the viewpoint character acquires the experience they’re reporting (by looking, thinking, feeling etc.) – it's worth keeping their use to a bare minimum. One nudge will likely be enough.

Further reading

- For editors: Fiction editing learning centre

- For authors: Line craft learning centre

- Becoming a Fiction Editor (free booklet for editors)

- Blacktop Wasteland, Cosby, S.A., Headline, 2020

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level (book for editors and authors)

- Filter words in fiction: Purposeful inclusion and dramatic restriction (blog post)

- Making Sense of ‘Show, Don’t Tell’ (book for editors and authors)

- Narrative Distance: A Toolbox for Writers and Editors (course)

- Razorblade Tears, Cosby, S.A., Headline, 2021

- Switching to Fiction (course for editors)

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

What’s in this post ...

- What is narrative distance?

- Are narrative distance and psychic distance the same thing?

- How is narrative distance related to narrative style?

- Why writers and editors need to learn about narrative distance

- Using a visual framework to understand narrative distance

- Related resources for you to dig into

What is narrative distance?

A narrator is the person who tells the story. They can be a character in the book or an entity that stands outside it.

There can be multiple narrators in a book, too. That allows the author to present events from multiple perspectives.

‘Narrative distance’ describes the space between a novel’s narrator and the reader.

- If we, as readers, feel deeply connected to the narrator and their experience of the fictional world they inhabit, narrative distance is tiny.

- If we feel dislocated from them, more like we’re looking out on the story’s landscape objectively, the narrative distance is wide.

Are narrative distance and psychic distance the same thing?

You might find one or other useful depending on what issues you’re dealing with when you’re writing or editing. I like the word ‘narrative’ because it reminds me what part of the prose I’m dealing with.

Then again, I sometimes use the word ‘psychic’ because it reminds me that although I’m dealing with fiction, and therefore something that’s not real, the narrator within that creative realm still has their own lived experience and a raft of emotions that come with that.

How is narrative distance related to narrative style?

- First-person limited

- Third-person limited

- Third-person objective

- Third-person omniscient

Each of those narrative styles come with a certain degree of distance between the narrator and the reader.

For example, first-person narrations always feel a little more intimate because the pronoun ‘I’ is used. Second-person narrations can feel equally intimate, but in a voyeuristic way.

Third-person narrations – and the pronouns that come with them – are what we’re used to using for those not being directly addressed, so in prose they naturally put space between readers and narrators using the third person.

When we move beyond a framework of narrative style and start to think specifically in terms of narrative distance, we’re able to analyse the effectiveness of prose in a more nuanced and flexible way.

Why writers and editors need to learn about narrative distance

Perhaps you’ve never noticed before, and if that’s the case, the author and their editor have done a great job because the movement is seamless.

If that movement is jarring and too obvious, it could be an indication that narrative distance isn’t being controlled sufficiently. Editors and writers who can recognize narrative distance and evaluate its effectiveness are better equipped to solve the problem, and justify their solutions.

Using a visual framework to understand narrative distance

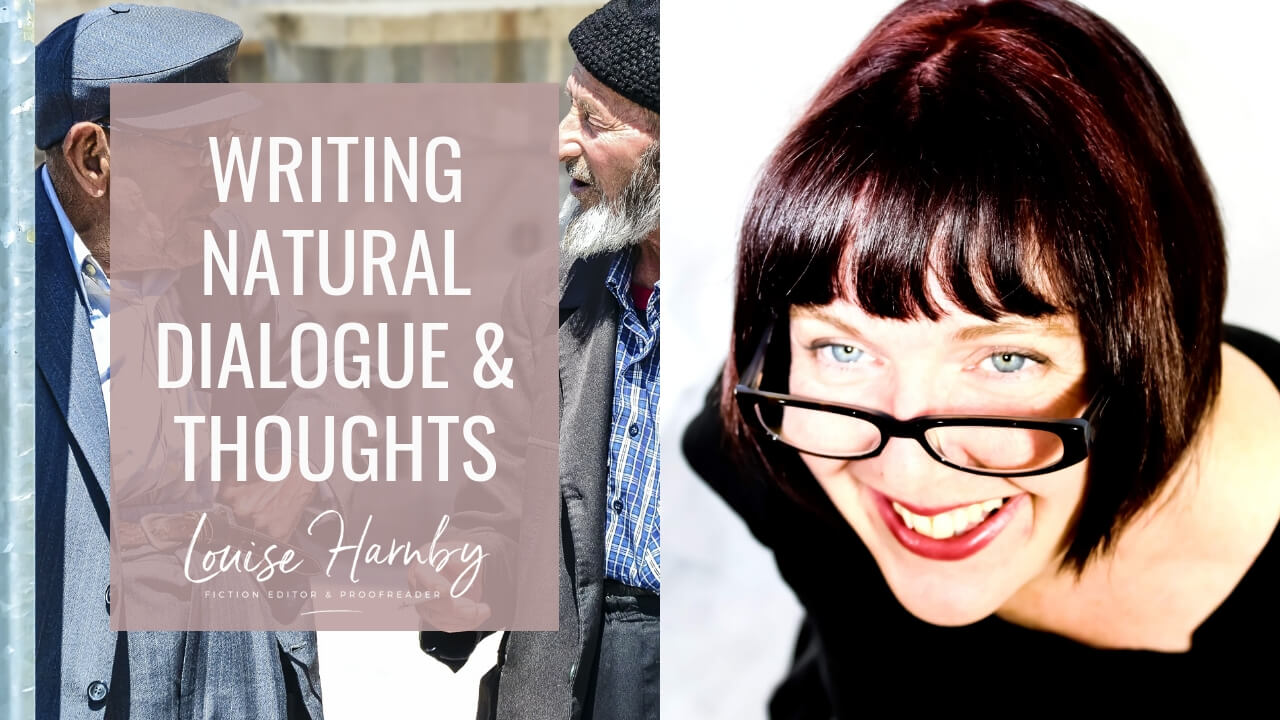

My solution was to structure my own learning as a visual framework. I presented that framework at the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading’s annual conference in September 2021 and then for the Society of Authors in October 2021.

The framework I shared at those two events garnered fabulous reviews and convinced me to record a webinar that everyone could access.

Narrative Distance: A Toolbox for Writers and Editors is available now to anyone who wants to lift the curtain on narrative distance and use it to craft prose that offers a better reader experience.

Use the button below to find out what’s included in the course.

|

If you’re a CIEP member, don’t forget that you can save 20% on all my courses. Log in to Promoted courses · Louise Harnby’s online courses. Then enter the coupon code at my checkout.

|

Related resources for you to dig into

- Blog post: 7 reasons why I’m not the right editor for you

- Blog post: How to avoid repeating ‘I’ in first-person writing

- Blog post: How to show the emotions of non-viewpoint characters

- Blog post: What’s the difference between a viewpoint character and a protagonist?

- Book: Editing Fiction at Sentence Level

- Book: Making Sense of Point of View

- Course: How to Write the Perfect Fiction Editorial Report

- Course: Switching to Fiction

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

In this post ...

- Clutter check #1: Reviewing filter words

- Clutter check #2: Reviewing speech tags

- Clutter check #3: Reviewing action beats

Clutter check #1: Review your filter words

Too many filter words that explain this sensory behaviour in action can make prose feel told rather shown, and increase narrative distance.

Examples include ‘noticed’, ‘seemed’, ‘spotted’, ‘saw’, ‘realized’, ‘felt’, ‘thought’, ‘wondered’, ‘believed’, ‘knew’ and ‘decided’.

Removing them focuses the reader’s gaze outwards on what is being experienced.

Sometimes an author wants an inward focus, but it’s often the case that the reader will assume that an odour is being smelled, a view is being seen, a thought is being thought, and knowledge is being known.

Review your narrative and consider whether the removal of a filter word would make the prose shorter and more immersive.

Here are some examples:

|

WITH FILTER

|

FILTER REMOVED

|

|

Danni knew there was a door in the back of the hut that led into the woods. She could make her escape there.

[Reader’s gaze focuses inwards on Danni’s doing the action of knowing.] |

There was a door in the back of the hut that led into the woods. She could make her escape there.

[Reader assumes it’s Danni doing the knowing since she’s the viewpoint character, and focuses outwards on the solution – the door.] |

|

The backdoor – it leads to the woods, Danni thought.

[Reader’s gaze focuses inwards on Danni’s doing the action of thinking.] |

The backdoor – it leads to the woods.

[Reader assumes the thought belongs to Danni, and focuses on the substance of the thought.] The backdoor – it led to the woods. [This alternative uses free indirect style; it frames the thought in the novel’s base tense and narrative style – third-person past.] |

|

He flung open the door and saw the gunman standing over by the window, rifle trained on the street below.

[Reader’s gaze focuses inwards on the man’s doing the action of seeing.] |

He flung open the door.

The gunman stood over by the window, rifle trained on the street below. [Reader assumes it’s the man doing the seeing since he’s the viewpoint character, and focuses outwards on the gunman.] |

Clutter check #2: Review speech tags

Review your dialogue tags and consider the following:

- Is the tag necessary?

- Is the tag taking centre stage?

- Is the tag illogical?

If there are only two characters in a scene, it might be obvious who’s speaking, which gives the author space to introduce reminder nudges only now and then.

|

ALL THE TAGS!

|

REDUCED TAGGING

|

|

‘There’s a door at the back of the hut,’ Danni said.

‘You’re sure it isn’t locked?’ I said. ‘No,’ she said. ‘Trish never locks it. Not since the fire.’ ‘And that’ll get us into the woods?’ I said. ‘Yup. There’s a track. It’s overgrown but I know the way. Used it all the time when I was young and foolish,’ she said. ‘What do you mean was?’ I said. ‘You’re too funny,’ she said, and pulled a face. |

‘There’s a door at the back of the hut,’ Danni said.

‘You’re sure it isn’t locked?’ ‘No. Trish never locks it. Not since the fire.’ ‘And that’ll get us into the woods?’ ‘Yup. There’s a track. It’s overgrown but I know the way. Used it all the time when I was young and foolish.’ ‘What do you mean was?’ I said. Danny pulled a face. ‘You’re too funny.’ |

Showy speech tags scream their presence from the page, and shift the reader’s attention away from the dialogue and onto the tag. They often tell what the dialogue’s already shown, and indicate a lack of trust in the reader to get the speech. Examples include ‘exclaimed’, ‘opined’, ‘commanded’

|

TAG TAKES CENTRE STAGE

|

DIALOGUE TAKES CENTRE STAGE

|

|

‘Watch out!’ Danni warned.

|

‘Watch out!’ Danni said.

|

|

‘Yup. There’s a track. It’s overgrown but I know the way. Used it all the time when I was young and foolish.’

‘What do you mean was?’ I joked. |

‘Yup. There’s a track. It’s overgrown but I know the way. Used it all the time when I was young and foolish.’

‘What do you mean was? |

|

EXPRESSION TAG

|

ACTION BEAT

|

|

‘No,’ Danni grimaced. ‘Trish never locks it. Not since the fire.’

|

‘No.’ Danni grimaced. ‘Trish never locks it. Not since the fire.’

|

|

EXPRESSION TAG

|

SPEECH TAG

|

|

‘Yup. There’s a track. It’s overgrown but I know the way. Used it all the time when I was young and foolish.’

‘What do you mean was?’ I laughed. |

‘Yup. There’s a track. It’s overgrown but I know the way. Used it all the time when I was young and foolish.’

‘What do you mean was?’ I said. |

Clutter check #3: Review action beats

They key to effective use is ensuring they amplify dialogue rather than interrupt it.

Think about movies. On the screen, all the actors movements and gestures are visible. Replicating this detail in a novel can be invasive and pull the reader away from what’s being unveiled through the speech.

While action beats are superb backdoors into the emotional space of non-viewpoint characters, the dialogue should be where the main action is taking place. If it’s not, what might be required is a reworking of the dialogue, not the introduction of more action beats.

Instead of mimicking the screen experience, use action beats to show what the dialogue doesn’t convey. That needn’t mean including them with every turn. Great dialogue doesn’t need to be anchored every time a character opens their mouth. A purposeful nudge now and then will be enough.

Watch out in particular for prose that’s overloaded with mundane action beats – legs stretching, fingers raking through hair, raised eyebrows, arms folding, fingers steepling.

Review your action beats:

- Do they tell the reader something the dialogue doesn’t or are they mundane details that a reader could imagine?

- Are they infrequent nudges or are they littering the dialogue at every turn of speech?

- Could the mood conveyed by the action beat be conveyed better by improving the dialogue?

Getting rid of the dull and redundant ones will reduce your word count. And what’s left on the page will be more engaging.

|

ACTION BEATS THAT INTERRUPT DIALOGUE

|

ACTION BEATS THAT AMPLIFY DIALOGUE

|

|

Danni pointed at the back of the cellar. ‘Over there. The door. It leads to the woods.’

‘You’re sure it isn’t locked?’ Max rubbed his forehead. ‘Maybe we need a Plan B.’ ‘No.’ Her brow furrowed. ‘Trish never locks it. Not since the fire.’ Max tilted his head. ‘The fire? What happened?’ ‘It was years ago.’ She waved his question away and jabbed a finger towards the door again. ‘Out back there’s a track. It’s overgrown but I know the way. Used it all the time when I was young and foolish.’ ‘What do you mean was?’ he said, and smirked. She pulled a face. ‘You’re too funny.’ |

Danni pointed at the back of the cellar. ‘Over there. The door. It leads to the woods.’

‘You’re sure it isn’t locked?’ Max said. ‘I dunno, maybe we need a Plan B.’ ‘No. Trish never locks it. Not since the fire.’ ‘The fire? What—’ ‘It was years ago. Whatever. Focus. Out back there’s a track. It’s overgrown but I know the way. Used it all the time when I was young and foolish.’ ‘What do you mean was?’ She pulled a face. ‘You’re too funny.’ |

Summing up

However, if they’re mundane or interruptive clutter that can be assumed, leave them out so we can focus on the words that really matter.

Related reading

- 3 reasons to use free indirect speech in your crime fiction

- Author writing resources

- Becoming a Fiction Editor (free booklet for editors)

- Dialogue tags and how to use them in fiction writing

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level (book for editors and authors)

- Filter words in fiction

- Making Sense of ‘Show, Don’t Tell’ (book for editors and authors)

- Switching to Fiction (course for editors)

- Tips on lean writing

- What are action beats and how can you use them in fiction writing?

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

What’s in this post

- to show rather than tell internal experience

- to decelerate reading speed

- to emphasize key information

- to create clutter-free immediacy

- to deliver suspenseful chapter finales

Showing rather than telling internal experience

The staccato rhythm of one-line paragraphs is interruptive, both rhythmically and visually. Each short line is its own single beat, one that’s structurally visible on the page. Every time the reader moves onto the next, they take mental breath.

Because the lines are short, the breaths come quickly, and it’s there that the author can show rather than tell a character's internal experience in a way that's rich in mood and voice.

In this excerpt from Recursion by Black Crouch, p. 317 (Pan, 2019), look at how the structure of those two initial short lines in bold mirrors the meaning of the words.

|

The memories arrive in a blink.

One moment nothing. The next, he knows exactly where he is, the full trajectory of his life since Helena found him, and exactly what the equations on the blackboard mean. Because he wrote them. They're extrapolations of the Schwarzschild solution, an equation that defines what the radius of an object must be, based upon its mass, in order to form a singularity. That singularity then forms an Einstein-Rosen wormhole that can, in theory, instantaneously connect far-flung regions of space and even time. |

One minute the memories aren’t there; the next they are. The beat of their arrival is reflected in the way the prose is formatted. We’re therefore shown how the viewpoint character experiences the lightning-speed download of knowledge, and as a result we feel it all the more intensely.

Decelerating reading speed

Such speedy reading can lead to skimming because we relax into the flow of the narrative. One-line paragraphs, however, stand out because they contrast so starkly with the longer passages, surrounded as they are by so much white space.

Text that stands out begs for our attention and forces us to slow down and focus on each word. And that means it’s not only the rhythm of the prose that’s changed; so has the rhythm of how we’re interacting with it as readers.

Take a look at this example on p. 470 of The Good Daughter by Karin Slaughter (HarperCollins, 2017).

|

There was more tapping, more tracking, and then colours on the screen were almost too much. The blacks were up so far that gray spots bubbled through the midnight fields.

Charlie suggested, “Use the blue on the lockers as a color guide. They’re close to the same blue as Dad’s funeral suit. Ben opened the color chart. He clicked on random squares. “That’s it,” Charlie said. “That’s the blue.” “I can clean it up more.” He sharpened the pixels. Smoothed out the edges. Finally, he zoomed in as close as he could without distorting the image into nothing. “Holy shit,” Charlie said. She finally got it. Not a leg, but an arm. Not one arm, but two. One black. One red. A sexual cannibal. A slash of red. A venomous bite. They had not found Rusty’s unicorn. They had found a black widow. |

The non-bold text is what we’re most used to seeing. It makes for a comfortable, leisurely, skimmable read. But when we get to the bold single-line paragraphs, the contrast is visible on the page. Our reading pace decelerates and our attention zooms in on every word.

Emphasizing key information

Because the one-liner stands out, it’s an opportunity for centre-staging. Here’s a great example from Harlan Coben’s Win, p. 38 (Century, 2021).

|

Respect, yes. Bow, no. I also don’t use these techniques,

per the platitude, “only for self-defense,” an obvious untruth on the level of “the check is in the mail” or “don’t worry, I’ll pull out.” I use what I learn to defeat my enemies, no matter who the aggressor happens to be (usually: me). I like violence. I like it a lot. I don’t condone it for others. I condone it for me. I don’t fight as a last resort. I fight whenever I can. I don’t try to avoid trouble. I actively seek it out. After I finish with the bag, I bench-press, powerlift, squat. When I was younger, I’d have various lifting days—arm days, chest days, leg days. When I reached my forties, I found it paid to lift less often and with more variety. |

Coben wants us to know something about his protagonist Windsor Horne Lockwood III, something we might find distasteful and hard to fathom. Nevertheless, it’s central to the characterization; Win’s actions throughout the novel don’t make sense unless we know this. Coben ensures we don’t miss it.

Creating clutter-free immediacy

This can reduce narrative distance – the space between the reader and the viewpoint character.

Here’s beautiful example from p. 296 of The Cold Cold Ground by Adrian McKinty (Serpent’s Tail, 2012)

|

“You had to stick your fucking neb in, didn’t ya? You had to open your big yapper. Can’t you fucking take a hint? After all them ciggies we give you too,” he said.

He raised the gun. I closed my eyes. Held my breath. A bang. Silence. When I opened my eyes again Bobby Cameron was staring at me and shaking his head. Billy White was dead to my left with the back of his head blown off. |

The narration is first person, so it’s already immersive. But the one-line paragraphs in bold drive us deeper into Sean Duffy’s experience. There’s no fluff, no filtering, no cluttering description.

Each moment of the action is presented oh so precisely, slamming us into the now of the novel – the weapon being raised, Duffy’s physical response, then what he hears: first a bang, then nothing.

In five lines and fourteen words, McKinty shows us something powerful – that he trusts us to get it. We don’t know for sure what Duffy is feeling. It could be sadness, terror, anger, resignation, or a combination of some or all those things.

The author’s had the courage to leave it to us, to allow us to imagine what this moment means internally for Duffy, rather than forcing us one way or another. In doing so, we get to be Duffy for a while rather than a fly on the wall. The narrative distance is so small, it’s barely perceptible.

Delivering suspenseful chapter finales

When that yearning is encapsulated in one line, it stands out and demands that we turn the page.

Here are the final two paragraphs from p. 132 of David Rosenfelt’s Open and Shut (Grand Central Publishing, 2002)

|

The next morning, to my undying shame, I did not withdraw my request. I had the time of my life at camp that summer, and I know now that my father, so desperate for me to go that he was in terrible pain, had millions of dollars that he refused to touch.

Money that he did not make delivering newspapers. [Chapter ends] |

There is only one question on the reader’s mind as the chapter closes: So how did his father make all that money?

And because the answer lies beyond – maybe in the next chapter, maybe right at the end of the book – we turn the page.

Why less is more

One-liners pack the biggest punch when they’re used now and then as a tool with which to vary the pulse of your prose and deepen your reader’s immersion in the world you’ve created.

Save them for best so that they stand out.

More writing and editing resources

|

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

What’s covered in this post

- Why reduce the ‘I’

- Why ‘I’ still has a place front and centre

- Focusing on the exterior rather than the interior

- Reducing the use of filter words

- Removing speech and thought tags

- Applying the principles of free indirect speech

- Taking the 'I' out of introspection

- Balancing ‘I’ with ‘we’

Why reduce the ‘I’

Too much ‘I’ is a tap on the shoulder, one that says to the reader, ‘Just in case you’ve forgotten who the narrator is, here are lots of reminders.’

The consequence is that readers are pulled away. And that can actually increase rather than reduce narrative distance.

Why ‘I’ still has a place front and centre

However, they don’t rely on a first-person pronoun to convey experience, thought, speech and action. Below, I'll show you some examples – ones that ensure the intimacy of the narration style is left intact.

And so while we don’t want to obliterate ‘I’, because avoiding it completely would render the prose awkward, inauthentic and overworked, too much ‘I’ can be repetitive and interruptive. What’s required is a balance.

This post aims to offer you choice – fitting alternatives that retain intimacy and immediacy when you’re concerned you’ve overdone it.

1. Focus on the exterior rather than the interior

A little peppering in a more objective report will suffice because the reader knows that it’s coming from the narrator, and only the narrator. It has to be.

And while writers can make space to explore the viewpoint character’s emotional behaviour, the exterior world is what grounds their experience in the novel’s physical world. It gives the novel substance, and the reader something to bite into.

Instead of focusing on who’s doing the reporting, shift the prose towards what’s being reported.

What and who else is in the scene? Why are they there? How do they behave? What do they look like? This information can be reported without ‘I’ so that the reader experiences the physical world within which the narrator is operating.

Here’s an example from To Kill a Mockingbird (Harper Lee, Pan, 1974, p. 11).

|

Maycomb was an old town, but it was a tired old town when I first knew it. In rainy weather the streets turned to red slop; grass grew on the sidewalks, the court-house sagged in the square. Somehow, it was hotter then; a black dog suffered on a summer’s day; bony mules hitched to Hoover carts flicked flies in the sweltering shade of the live oaks on the square. Men’s stiff collars wilted by nine in the morning. Ladies bathed before noon, after their three o’clock naps, and by nightfall were like soft tea-cakes with frostings of sweat and sweet talcum.

People moved slowly then. They ambled across the square, shuffled in and out of the stores around it, took their time about everything. A day was twenty-four hours long but seemed longer. There was no hurry, for there was nowhere to go, nothing to buy and no money to buy it with, nothing to see outside the boundaries of Maycomb County. But it was a time of vague optimism for some of the people: Maycomb County had recently been told that it had nothing to fear but fear itself. |

Notice the (almost) absence of ‘I’. Scout – our narrator – tells us about the town she lived in: Maycomb. The recollection is hers certainly – ‘when I first knew it’ anchors it as such. It’s therefore intimate.

And yet because there’s only one I-nudge, we’re allowed enough emotional distance to step back and pan, like a roving camera, across Maycomb’s vista. We’re dislocated from Scout’s doing the experiencing and encouraged instead to focus on what she’s experiencing.

What’s happening here is a shift from the subjective to the objective.

Here’s an example of a short excerpt that’s subjective. The focus is on the I-narrator.

And here’s the real excerpt from David Rosenfelt’s Play Dead (Grand Central, 2009, p. 19). Now the focus is objective, yet in no way does this distance us from the centrality of the first-person narrator’s experience. We’re still deep in his head.

2. Reduce the use of filter words

Examples include noticed, seemed, spotted, saw, realized, felt, thought, wondered, believed, knew, and decided.

Filter words focus the reader’s gaze inwards (interior focus) on the manner through which the viewpoint character experiences the world – the how.

They come with a pronoun: I saw, they believed, we decided, she knew, he noticed.

By removing filter words, the reader’s gaze is shifted outwards (exterior focus) and onto what is being experienced. That can make for a more immersive read. Plus, the omission means we say goodbye to their accompanying pronoun: 'I'.

Here are a few examples to give you a flavour of how you might recast in a way that avoids first-person filtering.

|

‘I’ plus filter word. Reader’s gaze is inwards, on the how

|

Recast: Reader’s gaze drawn outwards towards the what

|

|

I recall the argument we had last week.

|

Last week’s argument is still fresh in my mind.

|

|

I recognized the man’s face.

|

The man’s face was familiar.

|

|

I saw the guy turn left and dart into the alley.

|

The guy turned left and darted into the alley.

|

|

I spotted the red Chevy from yesterday parked outside the bank.

|

There, parked outside the bank, was the same red Chevy from yesterday.

|

|

I still feel ashamed about the vile words I unleashed even after all these years.

|

The vile words I unleashed still have the power to bathe me in shame even after all these years.

|

3. Remove speech and thought tags

This will work best if there are no more than two characters. Most writers don’t extend the omission for more than a few back-and-forths before they introduce a reminder tag or an action beat.

Watching out for unnecessary tags is good practice regardless of narration style, but with a first-person narration it’s a particularly efficient way to declutter ‘I’-heavy prose.

Take a look at this excerpt from David Rosenfelt’s Play Dead, pp. 194–5. There are two characters in this scene: Andy Carpenter, the protagonist and narrator, and Sam Willis, the non-POV character on the other end of the phone.

“The woman's name is Donna Banks. She lives in apartment twenty-three-G in Sunset Towers in Fort Lee. I don't have the exact address, but you can get it.”

“Pretty swanky apartment,” he says.

“Right. I want you to find out the source of that swank.”

“What does that mean?”

“I want to know how she can afford it. She doesn't work, and she's the widow of a soldier. Maybe her name is Banks because her family owns a bunch of them, but I want to know for sure.”

“Got it.”

“No problem?” I ask. I'm always amazed at Sam's ability to access any information he needs.

“Not so far. Anything else?”

“Yes. I left her apartment at ten thirty-five this morning. I want to know if she called anyone shortly after I left, and if so, who.”

“Gotcha. Which do you want me to get on first? Although neither will take very long.”

“I guess her source of income.”

“Then say it, Andy.”

“Say what?”

“Come on, play the game. You're asking me to find out where she gets her cash. So say it.”

“Sam …”

“Say it.”

“Okay. Show me the money.”

“Thatta boy. I'll get right on it.”

The exchange involves 19 speech elements within the thread, but only 3 speech tags, and only one of those marks our first-person narrator.

At no point do we lose track, and at no point are we distracted by repetitive ‘I said’s.

4. Apply the principles of free indirect speech

In a nutshell, free indirect speech offers the essence of first-person dialogue or thought but through a third-person viewpoint. The character’s voice takes the lead, but without the clutter of speech marks, speech tags, italic, or other devices to indicate who’s thinking or saying what.

Here’s an example of third-person narration. Notice the filter words ‘glanced’ and ‘noticed’, the italic present-tense thought, and the thought tag:

Let’s change that to a first-person narration. The filter words are still there and there’s a thought tag with the ‘I’ pronoun.

Here’s what the third-person version could look like in free indirect style. The filter words and tags are gone. It feels like a first-person thought but the base tense and third-person narration remain intact.

And now the first-person version. All I’ve done is swapped out the pronoun ‘his’ for ‘my’.

5. Take the ‘I’ out of introspection

However, when prose is littered rather than peppered with constructions such as I wasn’t sure if, I didn’t know whether, I wondered if, it can feel muddled and be laborious to read. The reader might respond: Well, of course you’re wondering. Who else could it be? You’re the narrator.

Worse, readers might think the narrator’s rather self-absorbed and unsure of themselves. While that might be necessary now and then, it’s problematic if it’s a staple because a narrator who’s always focused on themselves, and who never instils confidence in us, can’t tell the story as effectively.

Look out for ‘I’-centred introspection and experiment with statements and questions that allow the ‘I’ to be assumed.

Here are a few examples to show you how it might work.

|

‘I’-centred introspection

|

‘I’-less introspection

|

|

I wasn’t sure if Shami was a reliable witness but I couldn’t afford to ignore her, given what she’d divulged.

|

Was Shami a reliable witness? Maybe, maybe not. She couldn’t be ignored given what she’d divulged.

|

|

I still didn’t know who the killer was.

|

The killer’s identity was still a mystery.

|

|

I wondered whether Shami was a reliable witness.

|

Shami might or might not be a reliable witness.

Shami’s reliability as a witness was hardly a given. Shami’s reliability as a witness was questionable. |

6. Balance ‘I’ with ‘we’

This is an opportunity to frame the narrative around ‘we’ rather than just ‘I’.

Here’s an excerpt from To Kill a Mockingbird (p. 162) in which Scout, Harper Lee’s first-person narrator, frames the recollection around not just her own experience but those of the people she was hanging out with.

A wagonload of unusually stern-faced citizens appeared. When they pointed to Miss Maudie Atkinson's yard, ablaze with summer flowers, Miss Maudie herself came out on the porch. There was an odd thing about Miss Maudie – on her porch she was too far away for us to see her features clearly, but we could always catch her mood by the way she stood. She was now standing arms akimbo, her shoulders drooping a little, her head cocked to one side, her glasses winking in the sunlight.

The effect is powerful because we’re shown rather than told a sense of her belonging, of her being in a group, of the togetherness of that experience. And that intensifies our immersion in her world.

Summing up

Try recasting sentences that start with ‘I’ more objectively, so that the focus is on the what – the emotion, the object, the person, the action and so on – rather than the sense being used to experience it or the I-narrator doing the experience.

Use the principles of free indirect speech to reduce your ‘I’ count. It’s a tool that encourages a narrowing of narrative distance to such a degree that the reader feels deeply connected to the viewpoint character – more like we’re reading a thought than straight narrative.

As for speech and thought tags, you might not need as many as you think. The speaker can usually be identified without them if there are only two people in the conversation. Removing redundant tags is worth considering whichever narration style you’re writing in.

Related resources

- 3 reasons to use free indirect speech

- 6 ways to improve your novel right now

- Author resource library (includes links to free webinars)

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level: A Guide for Beginner and Developing Writers

- Filter words in fiction: Purposeful inclusion and dramatic restriction

- Making Sense of Point of View: Transform Your Fiction 1

- What is head-hopping, and is it spoiling your fiction writing?

- Switching to Fiction: Course for new fiction editors

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Why speech in a novel is different

Every line of dialogue should have a purpose. If it doesn’t, it probably shouldn’t be in your book.

It can take courage to remove words you've spent an age crafting but as I hope to show in the example below, readers don't need every little detail. Less is so often more!

A three-pronged approach to dialogue

When we focus on those three things, we avoid dull dialogue – conversations about the weather, how someone takes their tea or coffee, and courtesy statements such as ‘Hi, how are you?’

Voice tells us who characters are, what makes them tick – their fears, frustrations, hopes and dreams, identity, preferences.

Perhaps their speech is abrupt, rude, measured, polite, sweary or seductive.

When we change the way a character speaks, we change their voice. And that means we change them.

Characters can show us how they’re feeling via their dialogue.

Emotionally evocative speech allows readers to access the internal experience of a non-viewpoint character. And that makes it a powerful tool.

Perhaps their speech is abrupt, assertive, hesitant, forceful, pleading. Using the right words means the speech tags and narrative won’t need to be cluttered with further explanation.

Intention is another way of framing subtext. How characters speak tells us what they want.

Perhaps they’re asking questions for the purpose of discovery and understanding whodunit (doctors, lawyers, PIs and police officers regularly use dialogue in novels to this end). Dialogue can express a multitude of motivations.

Ask yourself what your character wants every time they open their mouth.

Example: Real but mundane dialogue

“Hi, Kevin,” I say.

“Hey, Andy. How you doin’?”

“Not too bad, thanks. Christ, it’s cold out though. I need something to warm me up. Gonna grab a coffee. Want one? Laurie, you?”

Kevin nods.

Laurie says, “Please. Milk and sugar.”

“So Kevin,” I say as I hand around the drinks, “we need to talk about Petrone.”

It’s the first chance I’ve had to tell Kevin about my meeting with the guy. I fill him in. When I get to the part where Petrone denied trying to have me killed, Kevin asks, “And you believed him?”

“I did.”

“Just because that’s what he said?”

I nod. “As stupid as it might sound, yes. I’ve had dealings with him before, and he’s always told me the truth, or nothing at all. And he had nothing to gain by lying.”

“Andy, the guy has had a lot of people murdered. How many confessions has he made?”

Were you enthralled by the welcome and refreshments section, or did you just wish we could get to the point? I think I know the answer!

The slimmed-down version

These meetings are basically of dubious value, since all we seem to do is list the things we don’t understand in our preparation for a trial we don’t know will even take place.

It’s the first chance I’ve had to tell Kevin about my meeting with Petrone. I fill him in. When I get to the part where Petrone denied trying to have me killed, Kevin asks, “And you believed him?”

“I did.”

“Just because that’s what he said?”

I nod. “As stupid as it might sound, yes. I’ve had dealings with him before, and he’s always told me the truth, or nothing at all. And he had nothing to gain by lying.”

“Andy, the guy has had a lot of people murdered. How many confessions has he made?”

What readers don’t care about

And so he leaves all of that out and lets the reader imagine that this stuff took place. And it’s enough. In the published novel, as opposed to the version I butchered, the first line of speech is “And you believed him.”

With that, we’re straight into Kevin’s incredulity and concern, and his desire to understand what the team is dealing with in regard to Petrone.

Meanwhile, Andy has his lawyer hat on. His initial reply is succinct, so that we are left in no doubt about his belief that Petrone was telling the truth, and that he is determined to reassure Kevin.

This is no-messing dialogue that focuses on story, not whether the speech is what we might actually hear – in its entirety – in real life.

It’s an excellent example of an author ensuring that every word counts and that there’s no bus-stop-talk filler.

Summing up

- Is every line relevant to the story?

- Is the character speaking with purpose or taking up ink/pixels on the page?

- Can mundane chitchat be removed without damaging sense and flow?

- Could the dull stuff be replaced with speech that deepens character?

Want the booklet version of this post? It's available on my Dialogue resources library. Click on the cover below to hop over to the page. Once you're there, choose the Booklets icon.

More fiction editing resources for authors and editors

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level

- Making Sense of ‘Show, Don’t Tell’

- Making Sense of Point of View

- Making Sense of Punctuation

- How to Write the Perfect Fiction Editorial Report

- Switching to Fiction

- The Differences Between Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Copyediting and Proofreading (free webinar)

- How to Punctuate Dialogue in a Novel (free webinar)

- Resource library: Dialogue and thoughts

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

FIND OUT MORE

> Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

> Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

> Learn: Books and courses

> Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Review your novel for 6 common problems. None involve major rewriting, just relatively gentle recasts that will improve your prose significantly, and make your reader's experience more immersive.

1. Assess invasive adverbs

2. Remove redundant filter words

3. Take the spotlight off speech tags

4. Pick up dropped viewpoint

5. Trim anatomy-based action

6. Turn intention into action

1. Assess invasive adverbs

However, overuse is often a symptom of an author telling us what’s already been shown, which means the adverbs are repetitive and cluttering. In the two examples that follow, they can be ditched because 'fidgeted' shows the nervousness, and the apology in the dialogue shows the regret.

- Jane fidgeted nervously with the napkin.

- ‘I’m so sorry to keep you waiting,’ she said with regret. ‘It’s been one of those days.’

- Jane fidgeted with the napkin.

- ‘I’m so sorry to keep you waiting,’ she said. ‘It’s been one of those days.’

Even when adverbs are telling us something new, consider elegant recasts that use stronger verbs but still keep readers in the moment.

- Jane turned around suddenly and ducked.

- Jane opened the shed door cautiously and peeked in.

- Jane spun around and ducked.

- Jane inched open the shed door and peeked in.

2. Remove redundant filter words

The reader is already experiencing the story through a viewpoint character. For that reason, we often don’t need to be told that they realize, see, think or feel anything. We’re already in their heads.

It’s telling what’s already been shown.

- Jane’s phone trilled. She glanced at the screen and saw that it was James calling again.

- Matthew felt a thumping in his temples and thought about how that third glass of wine had been a bad idea.

- Jane’s phone trilled. She glanced at the screen. James again.

- Mathew’s temples thumped. That third glass of wine had been a bad idea.

Filtering pulls us out of the deep, limited viewpoint. Worse, it’s repetitive and obvious. Jane has already looked at the screen so we know her eyes are doing the work; telling us that she saw as a result of her glancing is redundant.

In the example where Matthew’s the narrative viewpoint character, we needn’t be told he feels the thumping in his temples, since if he weren’t feeling it he couldn’t report it. Nor do we need to know he’s thinking about that third glass because we’re already in his head.

3. Take the spotlight off speech tags

Sometimes tags aren’t even necessary because it’s obvious who’s speaking. Other times, we can replace a tag with an action beat than conveys movement and emotion.

Readers should be focused on the dialogue. If a showy tag is necessary to convey a character’s voice or mood, the speech might need a rethink.

In the examples below, the speech tags do the following:

- tell what the punctuation’s already shown

- tell what the dialogue’s already shown

- tell us what the dialogue could have shown but doesn’t

- express non-speech-related behaviour

- 'That’s extraordinary!’ Jane exclaimed, and ran her index finger over the polished wood.

- ‘Put the damn thing down now. That’s an order, soldier,’ Reja commanded, raising her rifle.

- ‘Stop,’ Mathew pleaded.

- ‘I really need to hit the sack,’ James yawned.

ALTERNATIVES

- ‘That’s extraordinary!’ Jane ran her index finger over the polished wood.

- ‘Put the damn thing down now.’ Reja raised her rifle. ‘That’s an order, soldier.’

- ‘Stop,’ Mathew said. ‘I’m bloody begging you.’

- James yawned. ‘I really need to hit the sack.’

4. Pick up dropped viewpoint

- The viewpoint character reports what they can’t know.

- The reader is given access to non-viewpoint characters' internal experiences.

The viewpoint character reports what they can’t know

Reporting what can’t be known often comes with filter phrases such as 'could tell (that)' and 'knew (that)'.

In this example, John is the viewpoint character. We experience the story though his senses.

There, behind the desk, sat Reja, the girl he’d dated two decades earlier.

‘Sergeant John Davis,’ he said, and held out his hand. He could tell she didn’t remember him.

Actually he can’t tell any such thing. It might seem that way, but for all John knows, she could be hiding it because she has another agenda. Telling us that’s not the case removes any underlying suspense – stops us asking the question.

This might seem like a small slip but it’s the kind of thing that turns over all the power of a limited/deep viewpoint to an all-knowing narrator and rips apart the tight psychic distance between reader and the viewpoint character.

Here are two recasts that avoid the viewpoint drop:

There, behind the desk, sat Reja, the girl he’d dated two decades earlier.

‘Sergeant John Davis,’ he said, and held out his hand.

She showed no sign of recognizing him.

There, behind the desk, sat Reja, the girl he’d dated two decades earlier.

‘Sergeant John Davis,’ he said, and held out his hand.

There was no recognition on her face.

Non-viewpoint characters’ internal experiences

Here we’re talking about head-hopping. It’s when readers are able to access emotions, mood and thoughts of a non-viewpoint character. In the example that follows, Reja is the viewpoint character.

Bloody fool. Who did he think he was? Reja jammed her hat down over her ears. No way was she leaving with him.

John could have kicked himself. He shouldn’t have come on that strong. Not after what she’d been through.

The solution is to recast the text so that these emotions, mood and thoughts can be inferred or accessed externally – for example, through movement or speech – by the viewpoint character only. Here’s a possible recast.

Bloody fool. Who did he think he was? Reja jammed her hat down over her ears. No way was she leaving with him.

John palmed his forehead and spluttered an apology. ‘I shouldn’t have asked. Not after … well, you know.’

5. Trim anatomy-based action

In the example below, we might remove the obvious body parts and focus more specifically on the part of John's legs doing the kicking and the impact of his action. As for the gun-toter, the hands have been ditched.

John kicked out with his legs. The woman stumbled, righted herself and came at him again, pistol raised in her hands.

ALTERNATIVE

John kicked out, slamming his heel into her kneecap. The woman stumbled, righted herself and came at him again, pistol raised.

6. Turn intention into action

Jane squeezed the detergent into the porridge. Just a couple of squirts to give Alice a taste of her own medicine.

However, when an author means to show the how of an action but tells of intention to act, there’s a problem. The red flag to watch out for is 'to'.

We can check whether the focus is on point by asking a question: What action do we want to show the reader (via Jane)?

If we want to show the reader that Jane can lift her wrist – because that’s what the first example below is showing us – we can leave as is.

However, that's rather dull; it's more likely that we want to show that Jane is checking the time, and so a leaner alternative is more effective.

Jane lifted her wrist to look at her watch. Bang on two.

ALTERNATIVE

Jane checked her wristwatch. Bang on two.

Summing up

And don't worry about them at first-draft stage. Use that space to get the words on the page. Put your sentence-level editing craft in play with a later draft, and once your story's structure, plot and characterization have been fully developed.

Further reading

- Author resource library (includes links to free webinars)

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level: A Guide for Beginner and Developing Writers

- Making Sense of Point of View: Transform Your Fiction 1

- Making Sense of Punctuation: Transform Your Fiction 2

- ‘Playing with sentence length in crime fiction. Is it time to trim the fat?’

- ‘Playing with the rhythm of fiction: commas and conjunctions’

- ‘What is anaphora and how can you use it in fiction writing?’

- '2 ways to write about physical pain'

- 'What is head-hopping, and is it spoiling your fiction writing?'

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

FIND OUT MORE

> Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

> Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

> Learn: Books and courses

> Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Common examples are:

- there are/is/was/were

- it is/was

Take a look at the following pair. The first sentence is introduced by an expletive.

- There was a car parked outside the house.

- A car was parked outside the house.

When used well, expletives are enrichment tools that allow an author to play with a narrative voice’s register and the rhythm of sentences.

When prose is overloaded with them, it can feel cluttered with filler words that add nothing but ink on the page. At best, they widen the narrative distance between the reader and the POV character; at worst, they flatten a sentence and destroy suspense and tension.

Too much telling of what there is or was can rip the immediacy from a scene and encourage skimming. That’s a problem – it means the reader isn’t engaged and risks missing something.

Furthermore, if they’re not performing their rhythmic or emphasis role, expletives make sentence navigation more difficult because all they're doing is cluttering the prose.

Here's an example. Think I've overworked it? There are published books from mainstream presses with passages just like this made-up one.

It was a tiny room. There was a light switch with rust-coloured smudged fingermarks on the melamine surface. Was that blood? There was a noise coming from beyond on the back wall. It was a high-pitched whimper. Then there was silence. She held her breath and tiptoed forward.

Suddenly there was a scream.

The problem with the expletives in the passage above is that readers are bogged down in what there was rather than the viewpoint character's experience of discovery. Let's revise it to fix the problem.

The room was tiny. Rust-coloured fingermarks smudged the melamine surface of the light switch. Blood maybe. A noise came from beyond a door on the back wall. A high-pitched whimper. Then nothing. She held her breath and tiptoed forward.

A scream shattered the silence.

Notice how the narrative distance has been reduced in the revised passage. Now it's as if we're in the viewpoint character's head, moving with her second by second. We can focus on the room, the dried-blood fingermarks, the whimper, and the scream rather than the being of those things – their was-ness.

Removing the expletives and swapping in stronger verbs (smudged, shattered) enables us to tighten up the prose and introduce immediacy. And now there's no need for the told 'suddenly' – we experience the suddenness through the in-the-moment shattering.

As is always the case, obliterating expletives from a novel would be inappropriate because sometimes they're the perfect tool to help out with rhythm and emphasis.

The opening paragraph of Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities (p. 1) uses expletives galore, and masterfully at that. The repetition (anaphora) brings a steady rhythm to the passage that ensures the reader gives equal weight to the contrasting extremes – from best and worst to hope and despair.

The expletives introduce a detached sense of reportage that forces us forward rather than allowing us to dwell on any of the heavens or hells on offer. It’s simultaneously mundane and monstrous, and that's why it's magical.

And here’s an example from Dog Tags (p. 1) where omission of the expletive would rip the energy from the opening first line of the chapter and interfere with our understanding of which words we’re supposed to emphasize.

That was the USA Today headline on a piece that ran about me a couple of months ago.

Summing up

Grammatical expletives are a normal part of language and have every right to be in a novel. Overloading can destroy tension and make for a laboured narrative, but a purposeful peppering can amplify character emotion, moderate rhythm, and make space for the introduction of big themes in small spaces without sensory clutter.

Cited works and further reading

- Author resource library (includes links to free webinars)

- A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens, W. W. Norton & Company; Critical edition, 2020

- Dog Tags, David Rosenfelt, Grand Central Publishing, Reprint edition, 2011

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level: A Guide for Beginner and Developing Writers

- Making Sense of Punctuation: Transform Your Fiction 2

- ‘Playing with sentence length in crime fiction. Is it time to trim the fat?’

- ‘Playing with the rhythm of fiction: commas and conjunctions’

- 'Should I use a comma before coordinating conjunctions and independent clauses in fiction?'

- ‘What is anaphora and how can you use it in fiction writing?’

- 'Why "suddenly" can spoil your crime fiction'

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Reflexive pronouns can act as double tells by stating the obvious, and mar pace and tension.

Stating the obvious

- Max grabbed a fistful of dandelion leaves and shoved them into his mouth. Needs garlic, he thought to himself.

- Jenny wondered to herself about the dream – it had been so real, as if she’d had full control. And yet …

When it comes to internal musings, authors can ditch the reflexive pronouns. Thoughts take place inside a person’s head and, by definition, are offered only for the thinker – unless there’s telepathy going on in the novel!

Moderating pace and reducing tension

- Max ducked, rolled himself over the floor and grabbed the Browning. Fired out two shots. Both hit home.

- Ali sprinted down the street and swung herself into the shadows.

These are high-tension scenes. Max is in a shoot-out; Ali’s escaping danger. Every word stretches out the sentence. And as the sentence length loosens, so does the tension.

Look what happens when we remove the pronouns:

- Max ducked, rolled over the floor and grabbed the Browning. Fired out two shots. Both hit home.

- Ali sprinted down the street and swung into the shadows.

The sentences shorten, the pace increases – and so does the tension.

We shouldn’t omit all -self pronouns. There are occasions when a sentence works better with them. Sometimes they’re essential.

Clarity

In some cases, the pronoun is necessary for clarity. The reader can’t be sure of what the verb’s object is without it. In the examples below, removing the pronouns could leave the reader with questions: Ashamed of what? A promise to whom? Stop what? Consider whom an expert?

- Ordinarily, she’d have been ashamed of herself, but there was no guilt – not this time.

- I made a promise to myself never again to lose my rag over something so inconsequential.

- He couldn’t stop himself; it took five minutes to demolish the chocolate egg.

- I consider myself an expert, and no one will convince me otherwise.

Emphasis

The pronoun can be used to emphasize the person being discussed. Omission would leave the sentence grammatically intact but change the mood and pacing. In this case, it’s a judgement call on the author’s part.

- Sarah told me so herself.

- The queen herself told me.

- John hadn’t been the only one having a hard time. I myself had been suffering from anxiety at the time.

Sense

Some sentences don’t make grammatical sense without a reflexive pronoun. Remove them and the writing leaves more than questions: it’s unreadable.

- She had to defend herself from that monster – no two ways about it.

- Cass doused themself in perfume.

- Why shouldn’t he call himself the King of Hearts? Who cares if it sounds daft? Daft is good.

- He dragged himself to the top of the stairs.

At the top of this post, I offered examples of how -self pronouns can reduce tension. There will be occasions when an author wants to do exactly that.

- I was trying to make a new life for myself. That’s all there was to it.

- I was trying to make a new life. That’s all there was to it.

There’s a more staccato feel to the second version above that might jar if the author’s seeking a contemplative mood.

Still, too much self-ing can make even a stress-free scene overly wordy so it’s always worth thinking about whether a leaner version would be more immersive and get the reader from A to B faster.

In the first version of the triplets that follow, the pronouns introduce a chilled-out sense of laissez-faire to the movement. In the second I’ve omitted them. And in the third, I’ve ditched the mundane movement and focused on the essential beat.

- He found himself a chair and sat down.

- He found a chair and sat down.

- He sat down.

- Maxie busied themself with the coffee machine and settled down to read the letter.

- Maxie made a coffee and settled down to read the letter.

- Maxie read the letter.

- She got herself up and called Mel.

- She got up and called Mel.

- She called Mel.

It’s always worth an author spending a little time on thinking about how much micromanagement of a scene is necessary.

Will the reader care about the chair discovery, or that Maxie had a hot drink while they were reading the letter, or that the protagonist was no longer on the sofa when she called Mel?

Perhaps. If that stuff’s central to driving the novel forward, to reflecting mood, to grounding the character in the environment, the pronoun and the stage direction might be necessary. If it’s clutter that can be removed without damaging reader engagement, lean up the scene!

Summing up

Use reflexive pronouns when they’re necessary for clarity, sense and emphasis. Otherwise, consider leaner prose that focuses on what the reader needs to know to move forward in the story.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Contractions are a normal part of speech. They help us communicate faster and improve the flow of a sentence.

Watch the following videos and listen to the spoken words. They feature people with very different backgrounds, sharing different stories, and in situations that demand varying levels of formality.

- A philosopher presenting a TED Talk about why the universe exists

- A fictional lawyer questioning a witness

- A child reading a poem

- A drug dealer describing his criminal activity

- A reporter’s voiceover on a news programme

- A vicar giving a sermon in a UK church

- A queen broadcasting a message to the nation

The people talking have one thing in common: they use contractions when they speak ... most (though not all) of the time.

That’s why when we want to write natural dialogue – dialogue that flows with the ease of real-life speech – contractions work.

How contractions affect the flow of dialogue

Take a look at this excerpt from No Dominion by Louise Welsh (Kindle edition, John Murray, 2017).

Here’s the contraction-free recast. It reads awkwardly, and leaves us unconvinced that what’s in our mind’s ear bears any relation to what we would have heard had this been real speech. And that means we’re questioning the authenticity of the story rather than immersing ourselves in it.

Contractions and genre

Some authors avoid contractions because of the genre they’re writing in. You’re more likely to see this in historical fiction than contemporary commercial fiction but it’s not strictly genre-specific and is more an issue of authorial style.

Here’s an excerpt from a contemporary psychological mystery, The Wych Elm (Penguin, 2019, p. 71). Tana French uses contractions in the narrative and dialogue. The speech sounds natural; the narrative that frames it is informal.

Compare this with Our Mutual Friend (Wordsworth Editions, 1997, p. 235). Dickens, writing literary fiction in the 1860s, still uses contractions in dialogue, although he avoids them in his more formal but wickedly tart narrative.

|

‘We’ll bring him in,’ says Lady Tippins, sportively waving her green fan. ‘Veneering for ever!’

‘We’ll bring him in!’ says Twemlow. ‘We’ll bring him in!’ say Boots and Brewer. Strictly speaking, it would be hard to show cause why they should not bring him in, Pocket-Breaches having closed its little bargain, and there being no opposition. However, it is agreed that they must ‘work’ to the last, and that, if they did not work, something indefinite would happen. It is likewise agreed they are all so exhausted with the work behind them, and need to be so fortified for the work before them, as to require peculiar strengthening from Veneering’s cellar. |

Now look at Ambrose Parry’s The Way of All Flesh (Canongate Books, 2018). The authors (Parry is the pseudonym used by Chris Brookmyre and Marisa Haetzman) don’t avoid contractions completely but the sparing usage does give the dialogue a more archaic feel. Here’s an excerpt from p. 259.

I doubt anyone would be surprised when I say that the setting is 1847. And so it works. However, if the novel were set in 2019, there’d be a problem. We’d consider those characters unrealistically pompous and the dialogue overblown.

Contractions, pace and voice

The decision to use or avoid contractions is a tool that authors can use to deepen character voice.

Specific contracted forms might enable readers to imagine regional accents, social status and personality traits such as pomposity.

P.G. Wodehouse is a master of dialogue. Bertie Wooster is a wealthy young idler from the 1920s. Jeeves is his savvy valet. The dialogue between the two pops off the page and Wodehouse uses or avoids contractions to make the characters’ voices distinct.

- Jeeves’s speech is often uncontracted. This moderates the pace of the dialogue and helps to render his voice as serious, formal, patient and long-suffering.

- Bertie’s speech is often contracted. This accelerates the dialogue and helps to render his voice as flighty, foolish and careless.

You can see it in action in The Inimitable Jeeves (Kindle version, Aegitus, 2019).

|

‘Mr Little tells me that when he came to the big scene in Only a Factory Girl, his uncle gulped like a stricken bull-pup.’

‘Indeed, sir?’ ‘Where Lord Claude takes the girl in his arms, you know, and says—’ ‘I am familiar with the passage, sir. It is distinctly moving. It was a great favourite of my aunt’s.’ ‘I think we’re on the right track.’ ‘It would seem so, sir.’ ‘In fact, this looks like being another of your successes. I’ve always said, and I always shall say, that for sheer brains, Jeeves, you stand alone. All the other great thinkers of the age are simply in the crowd, watching you go by.’ ‘Thank you very much, sir. I endeavour to give satisfaction.’ |

In Oliver Twist (Wordsworth Classics, 1992, p. 8), Dickens contracts is not (ain’t) and them (’em) to indicate the low social standing of Mrs Mann, who runs a workhouse into which orphaned children are farmed.

|

‘Why, it’s what I’m obliged to keep a little of in the house, to put into the blessed infants’ Daffy, when they ain’t well, Mr Bumble,’ replied Mrs Mann as she opened a corner cupboard, and took down a bottle and glass. ‘I’ll not deceive you, Mr B. It’s gin.’

‘Do you give the children Daffy, Mrs Mann?’ inquired Bumble, following with his eyes the interesting process of mixing. ‘Ah, bless ’em, that I do, dear as it is,’ replied the nurse. ‘I couldn’t see ’em suffer before my very eyes, you know, sir.’ |

Contractions and their impact on stress and tone

You can use or omit contractions in order to force where the stress falls in a sentence.

Compare the following:

- ‘I can’t believe you said that,’ Louise said.

- ‘I cannot believe you said that,’ Louise said.

By not using a contraction in the second example, the stress on ‘cannot’ is harder. The change is subtle but evident. With can’t the mood is one of disbelief tempered with a whining tone; with cannot the disbelief remains but the tone is angry.

Here’s another excerpt from The Way of All Flesh (p. 140). The speaker is a surgeon, Dr Ziegler.

|

‘I believe it is important to provide the best possible care for the patients regardless of the manner in which they got themselves into their present predicament,’ Ziegler continued. ‘Desperate people are often driven to do desperate things. I have known young women to take their own lives because they could not face the consequences of being with child; and some because they could not face their families discovering it.’

|

Parry’s dialogue doesn’t just evoke a historical setting. The style of the speech affects the tone too. The voice is compassionate, the mood stoic. However, the lack of contractions renders the tone precise and careful.

On p. 142, Raven – a medical student turned sleuth – talks with the matron about medical charlatanry:

- ‘Aye, though there is worse,’ said Mrs Stevenson.

Using there is forces the stress on is, and in consequence the tone is resigned. With there’s the stress would have fallen on worse, and we might have assumed a more conspiratorial tone, as if she were about to divulge a secret.

Contractions and narration style

If you’re wondering whether to reserve your contractions for dialogue only, consider who the narrator is.

Let’s revisit Tana French (p. 1). The viewpoint character is a privileged man called Toby, the setting contemporary Dublin. What’s key here is that the narration viewpoint style is first person.

It is Toby who reports the events of the mystery; the narrative voice belongs to him. His narration register is therefore the same as his dialogue register – relaxed, colloquial – and the author, accordingly, retains the contractions in the narrative.

For sections written in third-person limited, the narrative voice would likely mirror the viewpoint character’s style of speaking. However, if you shift to a third-person objective viewpoint, where the distance between the characters and the readers is greater, the narrative might handle contractions differently to dialogue. It's a style choice you'll have to make.

Guidance from Chicago

Still a little nervous? Here’s some sensible advice from The Chicago Manual of Style, section 5.105:

Evaluate the sound

Here are three ways to help you evaluate the effectiveness of contracted or contracted-free dialogue:

1. Read the dialogue aloud: Is it difficult or awkward to say it? Does it sound unnatural to your ear? Do you stumble? Does it feel laboured, like you’re forcing the flow? If so, recast it with contractions. If the revised version is smoother, and the integrity of the setting is retained, go with the contracted forms.

2. Ask someone else to read the dialogue: Objectivity is almost impossible when it comes to our own writing. If the plan is that no one but you will ever read your book, write your dialogue the way you want to write it and leave it at that. If, however, you’re writing for readers too, and want to give them the best experience possible, fresh eyes (and ears) will serve you well.

You could even give your readers two versions of the dialogue sample – one with contractions and one without – and ask them which flows better and reads most naturally.

3. Head for YouTube: Dig out examples of speech by people whose backgrounds, environments and historical settings are similar to those of your characters. Watching characters in action will give you confidence to place on the page what can be heard from the mouths of those on the screen.

Summing up

Whether to use contractions or not in dialogue is a style choice. There are no rules. However, a style choice that renders dialogue stilted and unrealistic is not good dialogue.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

The impact of ‘before’ and ‘after’ in fiction writing: Tacit and explicit chronology of action

17/2/2020

Here’s what to look out for and how to fix the problem.

Why writers include ‘before’ and ‘after’

The inclusion of ‘before’ and ‘after’ to tell the order of play is not an indication of poor grammar – not at all. There’s nothing grammatically wrong with these constructions.

It’s also why writers sometimes use several adjectives with similar meanings rather than one strong one, or an adverbial phrase to fortify a weak verb.

Some authors also fear that their writing will come across as too ‘plain’ or ‘simple’. Chronological nudges are an attempt to ornament the prose.

Tacit chronology of action

The things that we do occur in a sequence; they have a chronology. This is as much the case in real life as it is on the screen, in an audiobook and in the pages of a novel. That chronology is tacit – we don’t need to explain it because it’s understood.

Take a look at this excerpt from The Devil’s Dice by Roz Watkins (p. 79, HQ, 2019):

Watkins doesn’t tell us explicitly that the shuddering occurred before the laptop was put down, or that the laptop was moved before the character shifted the cat onto their knee. And yet we know. The sequence of events is implied by the order in which she places each clause. It’s tacit.

- First thing that happens: shudders

- Next thing that happens: moves laptop

- Next thing that happens: manoeuvres cat

- Next thing that happens: leans

- Next thing that happens: inhales cat odour

And that’s the thing with strong line craft – it allows the reader to immerse themselves in the chronology of action by showing us, clause by clause, what’s transpiring, instead of tapping us on the shoulder and telling us.

Explicit chronology of action

Let’s recast the Watkins excerpt with some explicit taps on the shoulder:

I see this use of timeline nudges frequently in the fiction writing of less experienced authors, and it’s problematic when overused. Here’s why.

1. Some readers might feel patronized

Not every reader will notice the use of chronology nudges. But some will, and since no author wants to alienate a chunk of their readership, why push the story over a cliff when we can work out the sequence of events from the order of the words?

Telling readers that X was done before doing Y, or after doing Z, is akin to saying: ‘Hey, just in case you’re not clever enough, let me spell it out for you.’

It’s a dumbing-down that readers in the know won’t appreciate.

2. The inclusion is unnecessary

If you’re still not convinced, ask yourself whether the inclusion of ‘before’ or ‘after’ as timeline nudges is necessary. It often isn’t.

If a character’s shuddering occurs at the beginning of a sentence, the reader will assume that shuddering is what’s happening right now. If a new action follows that shuddering, the reader will assume that – just like in real life – the moment has passed and something else is happening in the new now of the novel.

3. The reader is focused on the wrong thing

When writers create immersive fiction, the reader feels as if they are in the moment – this is happening, now that, now the other.

‘Before’ and ‘after’ are distractions that focus the reader on when rather than what’s happening. The former is telling; the latter is showing.

4. There are more words than are necessary

Not enough words leaves readers hungry for clarity. Too many gives them indigestion. The artistry comes in the form of balance.

As long as the sequence of events can be understood by the reader, consider whether timeline nudges such as ‘before’ and ‘after’ are cluttering your prose.

Take a look at these pairs of narrative text, each of which has a shown tacit chronology and an alternative told explicit sequence. Which versions are more suspenseful? Which are most immediate? Which flow better when you read them out loud?

I’ve used examples from published fiction for the tacit versions, and taken a little artistic licence – altering them in ways their authors never intended – for the explicit chronologies.

In the original version, the ‘and’ between the initial breath and the walk into the kitchen is a fine example of the power of a conjunction. It’s almost invisible, which gives us the space to take that breath with the viewpoint character. And having taken it, we’re ready to go into the kitchen with them.

In the edited version, ‘before’ pulls us away from that moment. The tension has fallen out of the sentence.

|

The Dream Archipelago, Christopher Priest, Gollancz, 2009, p. 201

|

In the original version, it’s as if we’re in the room, watching the man as he smiles and leans back. There is space for that action to have its moment. Then he blows the smoke – that’s the new moment; we’ve left the other behind.

In the edited version, ‘after’ shoves us past the leaning back and smiling before we’ve had a chance to savour it. It’s already gone, even though we’re still reading about it.

|

Jurassic Park, Michael Crichton, Arrow, 2006, Prologue from Kindle edition

|