|

Love Twitter for engaging with other editorial and language professionals? We've got one tip for you: Don't engage with content you hate.

|

|

Check out these additional resources that will help you develop your fiction-editing business.

|

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

What's covered in this post

- How there are multiple Englishes with different spellings

- The difference between spelling style and voice

- A case study from the 007 files

- Overcoming ‘But it looks wrong’

- Adding regional flavour to voice

- 3 examples of when spelling inconsistency works

- A note on suffixes, dashes and quotation marks

Multiple Englishes, different spellings

Most words are spelled the same regardless of which English is in play, though there are many that aren’t, for example ‘color’/’colour’, ‘judgment’/‘judgement’, ‘harmonize’/‘harmonise’, ‘behavior’/‘behaviour’, ‘gray’/‘grey’, 'liter'/'litre'.

None are right or wrong, better or worse, or correct or incorrect. Rather, the way each version of English is spelled is about convention and style.

This post uses examples of American English (AmE) and British English (BrE) style to explain how to approach spelling/voice conundrums in fiction.

The difference between spelling style and voice

- How the words in a novel are spelled is for the most part a question of style.

- What a character says, thinks, feels, and the words used to report this on the page, is a question of voice. This is the case for dialogue and narrative.

Voice isn’t something that’s spelled. Rather, it’s something the reader experiences, ‘hears’ with their mind’s ear. It therefore follows the base spelling style, regardless of where the character comes from. With that in mind:

- If you’re writing fiction, decide on your spelling style and stick to it.

- If you’re editing for an author, identify the spelling style and aim for consistency.

The easiest way to illustrate how spelling consistency works is with a case study. Let’s take a peek into the world of 007!

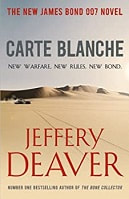

A case study from the 007 files

The version from Hodder & Stoughton (part of Hachette UK), published in 2011, is styled as follows:

‘Now, I’m ninety per cent sure he’ll believe you,’ Bond said. ‘But if not, and he engages, remember that under no circumstances is he to be killed. I need him alive. Aim to wound in the arm he favours, near the elbow, not the shoulder.’ Despite what one saw in the movies, a shoulder wound was usually as fatal as one to the abdomen or chest.

The Night Action alert meant an immediate response was required, at whatever time it was received. The call to his chief of staff had blessedly cut the date short and soon he had been en route to Serbia, under a Level 2 project order, authorising him to identify the Irishman, plant trackers and other surveillance devices and follow him.

The version from Pocket Star Books (a division of Simon and Schuster), published in 2012, is styled as follows:

“Now, I’m ninety percent sure he’ll believe you, Bond said. “But if not, and he engages, remember that under no circumstances is he to be killed. I need him alive. Aim to wound in the arm he favors, near the elbow, not the shoulder.” Despite what one saw in the movies, a shoulder wound was usually as fatal as one to the abdomen or chest.

The Night Action alert meant an immediate response was required, at whatever time it was received. The call to his chief of staff had blessedly cut the date short and soon he had been en route to Serbia, under a Level 2 project order, authorizing him to identify the Irishman, plant trackers and other surveillance devices and follow him.

Later in the novel (Chapter 26), Felix Leiter, an American, joins Bond on his mission. Here’s how Leiter’s dialogue is rendered in the AmE version:

And here it is in the BrE version. Leiter is still American and still has the same distinct voice, but now the spelling has changed (as has the punctuation; note the spaced en dash and single quotation marks).

Overcoming ‘But it looks wrong’

For example, perhaps they use idiomatic phrases that wedge them firmly in a country, state/province/county or even town/city that we’re from.

The British editor working on a book set in Southern California and written by an American author who writes in AmE might well struggle when a viewpoint character from Norfolk (the UK one where I live) turns up in Santa Barbara and mutters the following on seeing a cluster of huge ladybirds:

“Look at the color o’ them bishy barnabees. And big as a thruppence too!”

The spelling of ‘color’ might jar because ‘thruppence’ is so clearly unAmerican, so very British, while ‘bishy barnabees’ is particular to Norfolk. And yet the spelling is (and should be) AmE if that’s how the novel’s been styled overall.

An editor colleague recently reported this kind of problem in a Facebook group discussion. The novel was set in AmE, but the British viewpoint character spoke, thought and talked to herself in a Yorkshire accent. The first-person narration style deepened the voice still further.

‘The character's voice is really strong,’ the editor said, ‘and the US spelling seems at odds.’

The editor slept on it and the next day announced a simple but clever solution that had enabled her to overcome her resistance.

‘I mentally changed the British voice to a South African one so that I'm not so conscious of spelling variations, et voilà! It's suddenly clear as day.’

It’s a neat trick, a way of breaking the false connection between spelling and voice. If you come up against a similar situation, try it!

Adding regional flavour to voice

It’s worth bearing in mind, too, that language is often borrowed to the extent that some words no longer feel like, say, Britishisms, Americanisms, Canadianisms or Indianisms when they roll out of our mouths, regardless of how we identify or where we live.

Would I, a Brit, ever use the terms ‘cell phone’ and ‘movie’ rather than ‘mobile’ and ‘film’? Yes, I would.

How about ‘elevator’ rather than ‘lift’, ‘sidewalk’ rather than ‘pavement’, ‘aluminum’ rather than ‘aluminium’? Would I refer to ‘my mom’ rather than ‘my mum?’ Not while roaming around Norwich, but on a visit to Chicago, possibly, if I wanted to ensure people understood me. And almost definitely if I'd made my home there for some time.

Perhaps, then, the trick is not to be too precious about it, either when we’re writing or editing. Instead, we can consider the character’s environment and the degree to which the ‘local’ language flavour is something they’re likely to have assimilated into their speech, thoughts and narratives.

Those choices aside, the spelling style will be consistent. Unless …

3 examples of when spelling inconsistency works

The character is spelling a spelling

Imagine a Bond novel is styled in BrE. Bond and Leiter are speaking to each other on the phone and the line is terrible. Bond thinks Leiter has said ‘dissenter’. Leiter’s dialogue might go like this: ‘Not dissenter. The centre. C-E-N-T-E-R. Move to the centre.’

A proper noun is being referenced

Now imagine Bond’s telling Leiter that he’s received intelligence about a heist in the Rockefeller Center. Even if the novel’s styled in BrE, the AmE spelling of ‘Center’ should be retained because it’s referencing the name of a building.

Excerpts from written materials have been transcribed

Excerpts from diaries, newspaper cuttings, reports, letters, texts and so on can be rendered in the spelling style most likely used by whomever in the novel wrote them because they’re supposed to be authentic transcripts.

Imagine that Bond’s reading a document written by an American CIA operative. Even if the novel is styled in BrE, the spelling in the report would be AmE, unless referencing a proper noun that required a BrE spelling.

A note on suffixes, dashes and quotation marks

Suffixes

In AmE, it’s standard to spell with -iz- suffixes.

In BrE, both -iz- and -is- are standard. Again, it’s a matter of style.

Thus, in the Night Action alert excerpt above, if Hodder had elected to use ‘authorized’ instead of ‘authorised’, this would not have been a slippage into American spelling but a style choice – an accepted BrE variant that’s been around since the sixteenth century.

Dashes

While most US publishers favour closed-up em dashes and most British publishers favour spaced en dashes when used parenthetically (see the Leiter snippet in the case study), it’s not wrong to used unspaced em dashes when writing in BrE style; it’s Oxford’s preference, for example.

Quotation marks

Again, while it’s more common to see single quotation marks in BrE styling and doubles in AmE, this isn’t an unbreakable rule. Indie authors can choose, for example, BrE spelling and double quotation marks if they wish.

In all three cases, consistency is what counts.

Summing up

Spelling is about style. The goal is consistency in the main, complemented by good-sense deviation when necessary.

That’s how the mainstream publishing industry approaches it, and editors and writers will do well to follow their lead.

Related resources

- Author and editor resources library

- Blog post: How do I find spelling inconsistencies when proofreading and editing?

- Blog post: How to convey accents in fiction writing: Beyond phonetic spelling

- Blog post: What's the difference between a rule and a preference? Advice for new writers

- Booklet: British English and US English in your fiction, and why you should be consistent

- Podcast: Think it’s American? Think again!

- Podcast: Linguist Rob Drummond on grammar pedantry, peevery and youth language

Visit the grammar and spelling page in my resource library to download a free booklet summarizing suffix variations in American and British English.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

FIND OUT MORE

> Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

> Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

> Learn: Books and courses

> Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Listen to find out more about:

- Who are the grammar police?

- Social media and the grammar police

- Pedantry versus professional editing for style, preference and flow

- Writing style: Business, academia, web copy, creative non-fiction, fiction

- Conventions and standards versus rules and errors

- How and when to tell a writer about an error

- Dealing with the grammar police

Editing bites

- Blue Book of Grammar and Punctuation, by Jane Straus

- TextExpander

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

BLOG ALERTS

TESTIMONIALS

Dare Rogers

'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'

Jeff Carson

'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'

J B Turner

'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'

Ayshe Gemedzhy

'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'

Salt Publishing

'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'

CATEGORIES

All

Around The World

Audio Books

Author Chat

Author Interviews

Author Platform

Author Resources

Blogging

Book Marketing

Books

Branding

Business Tips

Choosing An Editor

Client Talk

Conscious Language

Core Editorial Skills

Crime Writing

Design And Layout

Dialogue

Editing

Editorial Tips

Editorial Tools

Editors On The Blog

Erotica

Fiction

Fiction Editing

Freelancing

Free Stuff

Getting Noticed

Getting Work

Grammar Links

Guest Writers

Indexing

Indie Authors

Lean Writing

Line Craft

Link Of The Week

Macro Chat

Marketing Tips

Money Talk

Mood And Rhythm

More Macros And Add Ins

Networking

Online Courses

PDF Markup

Podcasting

POV

Proofreading

Proofreading Marks

Publishing

Punctuation

Q&A With Louise

Resources

Roundups

Self Editing

Self Publishing Authors

Sentence Editing

Showing And Telling

Software

Stamps

Starting Out

Story Craft

The Editing Podcast

Training

Types Of Editing

Using Word

Website Tips

Work Choices

Working Onscreen

Working Smart

Writer Resources

Writing

Writing Tips

Writing Tools

ARCHIVES

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

October 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

October 2016

September 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

March 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

November 2015

October 2015

September 2015

July 2015

June 2015

May 2015

March 2015

February 2015

January 2015

November 2014

October 2014

September 2014

August 2014

July 2014

June 2014

March 2014

January 2014

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

August 2013

June 2013

February 2013

January 2013

November 2012

October 2012

September 2012

August 2012

July 2012

June 2012

May 2012

April 2012

March 2012

February 2012

January 2012

December 2011

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed