|

Find out about 5 core character roles within a novel, and how the purpose they serve ensures the story stays focused.

|

|

Example from published fiction

Kate Hamer, The Girl in the Red Coat, Faber & Faber, 2015 (Kindle edition, Chapter 6) When I wake up in the morning everything's wonderful. For a moment I can't understand why. Then I remember: Mum's said if the weather's good we can go to the storytelling festival and that's today. |

Description beats

They help readers understand what characters are wearing, what they look like, what’s surrounding them, what they can hear, see, smell, touch or taste. That brings the scene alive.

|

Example from published fiction

Harlan Coben, Win, Arrow, 2021 (Kindle edition, Chapter 1) His name is Teddy Lyons. He is one of the too-many assistant coaches on the South State bench. He is six foot eight and beefy, a big slab of aw-shucks farm boy. Big T—that's what he likes to be called—is thirty-three years old, and this is his fourth college coaching job. From what I understand, he is a decent tactician but excels at recruiting talent. |

Dialogue beats

Like action beats, dialogue is an opportunity to bring depth to non-viewpoint characters in limited narrative styles. Their internal opinions and feelings – which we don’t have access to because we’re not in their heads – are revealed to us.

Why mixing up beats makes scenes more interesting

Writers and their publishing teams can use the drafting and editing stages to analyse the prose and evaluate whether there’s sufficient balance.

How to analyse a scene for beat balance

Approach 1

One way of approaching this is to think not in terms of the different types of beats but instead in terms of what they contribute, and whether there’s too much or too little.

And so writers and their editors can ask: Which of the following should the reader experience in this scene, and are they present? Here’s a summary of those elements:

- Sensibility (via emotion beats)

- Movement (via action beats)

- Breathing space (via inaction beats)

- Stability (via description beats)

- Expression (via dialogue beats)

An over-reliance on dialogue – even if it’s extremely well written – leaves a reader with no nudges about the emotions characters are experiencing or the environment they’re operating in. It’s two or more talking heads on a page.

If there should be expression in the scene, but the characters are chattering too much, think how you might turn the volume down, or at least disrupt it.

Consider introducing a few action, description and emotion beats. Or even turn some of the information contained within the speech into narrative.

An over-reliance on objective description – even if it gives the reader a rich sense of the environment – leaves readers with no way of accessing mood. It’s a menu of what’s where.

Description should stabilise the scene, not crush it so that it’s as flat as a pancake.

Help readers get under the skin of the characters and their environment by adding emotion or dialogue, or a little action that gives the scene some movement.

An over-reliance on emotion can be draining and doesn’t give the reader the chance to take a breath. It’s like a counselling session.

If there should be emotion, but a character’s self-absorption is swamping a reader’s ability to make sense of the environment, introduce description and action beats to ground the reader a little more objectively.

|

Approach 2

Another option is to colour-code the text in a scene according to what type of beats are in play. This can help authors and editors evaluate whether one type of beat is overbearing, and where they might add in additional types of beat to disrupt that dominance. It's a powerful way of communicating the problem visually and quickly. |

Summing up

Other resources you might like

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level: book

- Fiction editing line craft: books

- How to Line Edit for Suspense: multimedia course

- How to Write the Perfect Editorial Report: multimedia course

- Narrative Distance: multimedia course

- Resource library

- Switching to Fiction: multimedia course

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 96

- What's distinctive about editing crime fiction and thrillers

- What a good line editor needs to look out for

- What new entrants to the field need to study

- Marketing ideas

- Top tips for being a successful freelance editor/proofreader

- Do fiction editors use style guides?

Related resources

Join our Patreon community

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

What’s in this post ...

- Why the start of a sentence is important.

- What filter words are.

- How filter words reduce momentum.

- How filter words make space for reflection.

Why the start of a sentence is important

While a novel that reads like a Google snippet from start to finish isn’t likely to win any prizes, the principle is worth paying attention to because the information at the start of a novel’s sentence is still what the reader will pay most attention to.

The start of a sentence is therefore valuable real estate. If filter words are being assigned to that top spot too often, more interesting subjects and verbs are likely being demoted.

What are filter words?

- Sunlight filtered through the tree canopy.

- Over the next couple of hours, information about the explosion filtered out of the camp.

- The children filtered through the turnstile and lined up in in yard.

In literature, filter words are verbs that do a similar thing – they slow down the reader’s access to what the viewpoint character is experiencing.

Examples include 'watched', 'saw', 'noticed', 'spotted', 'looked at', 'felt', 'thought', 'wondered', 'heard', 'realised' and 'knew'.

Take a look at this short excerpt from Chapter 2 of Razorblade Tears by S.A. Cosby.

Ike is the viewpoint character, which means we experience the scene from his perspective.

Notice first what’s front-loading those two sentences. The subjects (Ike in the first, ‘she’ – Ike’s wife – in the second) and the verbs ‘let go’ and ‘slumped’.

That front-loading forces our gaze outwards – first towards Ike, then towards the movement of Ike’s wife’s body.

Now let’s introduce a filter word.

Now the second sentence is front-loaded with a new verb – ‘watched’. Our access to the movement (the slumping) has been slowed down. We can’t shift directly to it without taking an extra step that involves centring our gaze for just a second on Ike’s watching.

In that brief moment, we’re no longer looking outward at what Ike’s experiencing. Instead, we’re looking inward at Ike and how he acquires that experience – by watching.

Less experienced writers can be tempted to overuse filter words. Indeed, it’s one of the most common problems I see in my editing studio. At sentence-level revision stage – whether that work’s being done by the writer themselves or with the help of a professional editor – it’s therefore worth watching out for them and assessing whether they’re impeding the novel’s pace.

When filter words reduce momentum

Problematic filter words can appear anywhere in a sentence, but front-loading sentences with them is even more likely to rip the momentum out of the prose. If you want your readers to focus on the action, make sure that any you retain are earning their keep.

Take a look at an excerpt from a published thriller that I’ve fiddled with. It’s a heist scene and the action takes place in a matter of seconds. The viewpoint character is coked up to his eyeballs and desperate, acting on impulse.

Ronnie struck the manager just above her right eye with the butt of the .38. He watched as a divot the width of a popsicle stick appeared above her eye. Blood spewed from the wound like water from a broken faucet.

The three instances of filtering moderate the pace and draw our attention towards the narrator’s doing knowing, thinking and watching, none of which are as interesting as what he knows, thinks and watches. All those filter words act as barriers that the reader has to jump over in order to get to the action.

We could even argue that they introduce a sort of voyeurism – as if Ronnie is reflecting on the impact of his violence, almost in slow motion. But that’s not what’s going on here. Rather, he’s wired, out of control and operating in the moment.

And that’s why the unadulterated version of Blacktop Wasteland (p. 113) – also by S.A. Cosby – is perfect:

|

Under normal circumstances he would never put his hands on a lady. However, these were not normal circumstances. Not by a long shot.

Ronnie struck the manager just above her right eye with the butt of the .38. A divot the width of a popsicle stick appeared above her eye. Blood spewed from the wound like water from a broken faucet. |

The filter words have gone, and with them the unintended pathological introspection, but the momentum is restored. We're in the moment with Ronnie as he lashes out. It's no less violent but the pace of the prose now mirrors the action authentically.

When filter words make space for reflection

Let’s take a look at another example from Cosby’s Razorblade Tears, this one also from Chapter 2.

The filter phrase is ‘looked at’, and it’s important. Ike is looking hard at what’s in front of him. As will be revealed later, this girl is his murdered son’s daughter. Ike recalls something he’d said to his son a few months earlier: ‘But that little girl, she gonna have it hard enough already. She's half Black. Her mama was somebody you paid to carry her, and she got two gay daddies. So now what?’

Ike and his wife will now be raising the little girl. Cosby wants to focus our attention inward for a moment on Ike’s reflection, and the filter word makes space for that.

While filter words can be effective when they’re used to create a sense of introspection, littering prose with them will be disruptive and pull the reader out of the viewpoint character's headspace. In other words, the psychic or narrative distance will be widened and we’ll feel disconnected from the immediacy of the character’s experience.

For that reason, always use filter words judiciously. In the above example, Cosby offers just a single nudge, and it’s enough.

Summing up

- When filter words front-load a sentence, they’re the first thing a reader notices.

- They destroy momentum and so are often best avoided in pacy action scenes, regardless of their position.

- And even if they do serve a purpose – focusing a reader’s attention inwards on how the viewpoint character acquires the experience they’re reporting (by looking, thinking, feeling etc.) – it's worth keeping their use to a bare minimum. One nudge will likely be enough.

Further reading

- For editors: Fiction editing learning centre

- For authors: Line craft learning centre

- Becoming a Fiction Editor (free booklet for editors)

- Blacktop Wasteland, Cosby, S.A., Headline, 2020

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level (book for editors and authors)

- Filter words in fiction: Purposeful inclusion and dramatic restriction (blog post)

- Making Sense of ‘Show, Don’t Tell’ (book for editors and authors)

- Narrative Distance: A Toolbox for Writers and Editors (course)

- Razorblade Tears, Cosby, S.A., Headline, 2021

- Switching to Fiction (course for editors)

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

In this post ...

- Clutter check #1: Reviewing filter words

- Clutter check #2: Reviewing speech tags

- Clutter check #3: Reviewing action beats

Clutter check #1: Review your filter words

Too many filter words that explain this sensory behaviour in action can make prose feel told rather shown, and increase narrative distance.

Examples include ‘noticed’, ‘seemed’, ‘spotted’, ‘saw’, ‘realized’, ‘felt’, ‘thought’, ‘wondered’, ‘believed’, ‘knew’ and ‘decided’.

Removing them focuses the reader’s gaze outwards on what is being experienced.

Sometimes an author wants an inward focus, but it’s often the case that the reader will assume that an odour is being smelled, a view is being seen, a thought is being thought, and knowledge is being known.

Review your narrative and consider whether the removal of a filter word would make the prose shorter and more immersive.

Here are some examples:

|

WITH FILTER

|

FILTER REMOVED

|

|

Danni knew there was a door in the back of the hut that led into the woods. She could make her escape there.

[Reader’s gaze focuses inwards on Danni’s doing the action of knowing.] |

There was a door in the back of the hut that led into the woods. She could make her escape there.

[Reader assumes it’s Danni doing the knowing since she’s the viewpoint character, and focuses outwards on the solution – the door.] |

|

The backdoor – it leads to the woods, Danni thought.

[Reader’s gaze focuses inwards on Danni’s doing the action of thinking.] |

The backdoor – it leads to the woods.

[Reader assumes the thought belongs to Danni, and focuses on the substance of the thought.] The backdoor – it led to the woods. [This alternative uses free indirect style; it frames the thought in the novel’s base tense and narrative style – third-person past.] |

|

He flung open the door and saw the gunman standing over by the window, rifle trained on the street below.

[Reader’s gaze focuses inwards on the man’s doing the action of seeing.] |

He flung open the door.

The gunman stood over by the window, rifle trained on the street below. [Reader assumes it’s the man doing the seeing since he’s the viewpoint character, and focuses outwards on the gunman.] |

Clutter check #2: Review speech tags

Review your dialogue tags and consider the following:

- Is the tag necessary?

- Is the tag taking centre stage?

- Is the tag illogical?

If there are only two characters in a scene, it might be obvious who’s speaking, which gives the author space to introduce reminder nudges only now and then.

|

ALL THE TAGS!

|

REDUCED TAGGING

|

|

‘There’s a door at the back of the hut,’ Danni said.

‘You’re sure it isn’t locked?’ I said. ‘No,’ she said. ‘Trish never locks it. Not since the fire.’ ‘And that’ll get us into the woods?’ I said. ‘Yup. There’s a track. It’s overgrown but I know the way. Used it all the time when I was young and foolish,’ she said. ‘What do you mean was?’ I said. ‘You’re too funny,’ she said, and pulled a face. |

‘There’s a door at the back of the hut,’ Danni said.

‘You’re sure it isn’t locked?’ ‘No. Trish never locks it. Not since the fire.’ ‘And that’ll get us into the woods?’ ‘Yup. There’s a track. It’s overgrown but I know the way. Used it all the time when I was young and foolish.’ ‘What do you mean was?’ I said. Danny pulled a face. ‘You’re too funny.’ |

Showy speech tags scream their presence from the page, and shift the reader’s attention away from the dialogue and onto the tag. They often tell what the dialogue’s already shown, and indicate a lack of trust in the reader to get the speech. Examples include ‘exclaimed’, ‘opined’, ‘commanded’

|

TAG TAKES CENTRE STAGE

|

DIALOGUE TAKES CENTRE STAGE

|

|

‘Watch out!’ Danni warned.

|

‘Watch out!’ Danni said.

|

|

‘Yup. There’s a track. It’s overgrown but I know the way. Used it all the time when I was young and foolish.’

‘What do you mean was?’ I joked. |

‘Yup. There’s a track. It’s overgrown but I know the way. Used it all the time when I was young and foolish.’

‘What do you mean was? |

|

EXPRESSION TAG

|

ACTION BEAT

|

|

‘No,’ Danni grimaced. ‘Trish never locks it. Not since the fire.’

|

‘No.’ Danni grimaced. ‘Trish never locks it. Not since the fire.’

|

|

EXPRESSION TAG

|

SPEECH TAG

|

|

‘Yup. There’s a track. It’s overgrown but I know the way. Used it all the time when I was young and foolish.’

‘What do you mean was?’ I laughed. |

‘Yup. There’s a track. It’s overgrown but I know the way. Used it all the time when I was young and foolish.’

‘What do you mean was?’ I said. |

Clutter check #3: Review action beats

They key to effective use is ensuring they amplify dialogue rather than interrupt it.

Think about movies. On the screen, all the actors movements and gestures are visible. Replicating this detail in a novel can be invasive and pull the reader away from what’s being unveiled through the speech.

While action beats are superb backdoors into the emotional space of non-viewpoint characters, the dialogue should be where the main action is taking place. If it’s not, what might be required is a reworking of the dialogue, not the introduction of more action beats.

Instead of mimicking the screen experience, use action beats to show what the dialogue doesn’t convey. That needn’t mean including them with every turn. Great dialogue doesn’t need to be anchored every time a character opens their mouth. A purposeful nudge now and then will be enough.

Watch out in particular for prose that’s overloaded with mundane action beats – legs stretching, fingers raking through hair, raised eyebrows, arms folding, fingers steepling.

Review your action beats:

- Do they tell the reader something the dialogue doesn’t or are they mundane details that a reader could imagine?

- Are they infrequent nudges or are they littering the dialogue at every turn of speech?

- Could the mood conveyed by the action beat be conveyed better by improving the dialogue?

Getting rid of the dull and redundant ones will reduce your word count. And what’s left on the page will be more engaging.

|

ACTION BEATS THAT INTERRUPT DIALOGUE

|

ACTION BEATS THAT AMPLIFY DIALOGUE

|

|

Danni pointed at the back of the cellar. ‘Over there. The door. It leads to the woods.’

‘You’re sure it isn’t locked?’ Max rubbed his forehead. ‘Maybe we need a Plan B.’ ‘No.’ Her brow furrowed. ‘Trish never locks it. Not since the fire.’ Max tilted his head. ‘The fire? What happened?’ ‘It was years ago.’ She waved his question away and jabbed a finger towards the door again. ‘Out back there’s a track. It’s overgrown but I know the way. Used it all the time when I was young and foolish.’ ‘What do you mean was?’ he said, and smirked. She pulled a face. ‘You’re too funny.’ |

Danni pointed at the back of the cellar. ‘Over there. The door. It leads to the woods.’

‘You’re sure it isn’t locked?’ Max said. ‘I dunno, maybe we need a Plan B.’ ‘No. Trish never locks it. Not since the fire.’ ‘The fire? What—’ ‘It was years ago. Whatever. Focus. Out back there’s a track. It’s overgrown but I know the way. Used it all the time when I was young and foolish.’ ‘What do you mean was?’ She pulled a face. ‘You’re too funny.’ |

Summing up

However, if they’re mundane or interruptive clutter that can be assumed, leave them out so we can focus on the words that really matter.

Related reading

- 3 reasons to use free indirect speech in your crime fiction

- Author writing resources

- Becoming a Fiction Editor (free booklet for editors)

- Dialogue tags and how to use them in fiction writing

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level (book for editors and authors)

- Filter words in fiction

- Making Sense of ‘Show, Don’t Tell’ (book for editors and authors)

- Switching to Fiction (course for editors)

- Tips on lean writing

- What are action beats and how can you use them in fiction writing?

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Listen to find out more about

- Doing your own narration vs hiring a pro

- How to find a professional voice artist

- Which qualities are important

- The process of working with a professional narrator

- Obstacles to creating audio books

- Costs and time frame

Here's where you can find out more about David Unger's books.

Dig into these related resources

- Author resources

- Book: Editing Fiction at Sentence Level

- The Editing Podcast: 6 ways to use audio for book promotion

- Booklet: How to narrate your own audio book

- Podcast episodes: The indie author collection

- Blog post: Why editors and proofreaders should be using audio

- Blog post: 5 ways to use audio for book marketing and reader engagement

- Blog post: How to go mobile with audio: Book-editor podcasting on the go

Music Credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Listen to find out more about

- What made David want to start writing and who inspired him

- Writing an alter ego

- The revision process

- On being edited

Here's where you can find out more about David Unger's books.

Dig into these related resources

- Author resources

- Book: Editing Fiction at Sentence Level

- Blog post: 3 reasons to use free indirect speech in your crime fiction

- Blog post: Crime fiction subgenres: Where does your novel fit?

- Blog post: How to write dialogue that pops

- Blog post: Playing with sentence length in crime fiction. Is it time to trim the fat?

- Blog post: Writing a crime novel – should you plan or go with the flow?

- Podcast episodes: The indie author collection

Music Credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Here's what two industry-recognized style guides have to say on the matter.

New Hart’s Rules (Oxford University Press): ‘You might have been taught that it’s not good English to start a sentence with a conjunction such as and or but. It’s not grammatically incorrect to do so, however, and many respected writers use conjunctions at the start of a sentence to create a dramatic or forceful effect.’

Chicago Manual of Style Online, 5.203 (Chicago University Press): ‘There is a widespread belief—one with no historical or grammatical foundation—that it is an error to begin a sentence with a conjunction such as and, but, or so. In fact, a substantial percentage (often as many as 10 percent) of the sentences in first-rate writing begin with conjunctions. It has been so for centuries, and even the most conservative grammarians have followed this practice.'

6 good reasons to start a sentence with ‘And’ or ‘But’

Great! We have the go-ahead from a couple of big hitters to use our two conjunctions at the beginning of a sentence. Now let’s dig a little deeper into why doing so can make fiction more effective. Here are my top six reasons:

- To serve natural speech

- To shorten narrative distance

- To introduce tension and suspense

- To add drama

- To emphasize the unexpected

- To make contrast explicit

Serving natural speech

When we speak in real life, conjunctions are often the first things out of our mouths. So it should be in novels that want to render speech authentically.

Fictional dialogue doesn’t replicate real-life speech completely – that would mean including a lot of boring stuff that one might hear at the bus stop. Rather, it’s a sort of hybrid that has the essence of reality but with the mundanity judiciously removed. It might sound like a cheat but readers thank authors who don’t bore them!

Small nudges towards reality help with the authenticity goal, which is where our conjunctions come in handy. Here are a few examples for you:

|

‘And you will have no hesitation in doing what has to be done? You have no doubts?’ (At Risk, Stella Rimington, p. 187)

‘And where’s he getting the money from? You know the situation as well as I do. He isn’t on leave of absence from a university.’ (The Dream Archipelago, Christopher Priest, p. 227) “But your way makes more sense. So you think Maura was working with Rex?” “I do.” “Doesn’t mean she didn’t set Rex up.” “Right.” “But if she wasn’t involved in the murder, where is she now?” (Don’t Let Go, Harlan Coben, p. 76) |

Shortening narrative distance

Dialogue gives us the character’s speech; narrative gives us the character’s experience. When that’s a first-person narrative, it’s easy to feel close to the narrator. With a third-person narration, the reader can feel separated from the character, as if they’re on the outside looking in.

Authors who want to reduce that space between the reader and the character – called narrative distance or psychic distance – can experiment with a narration style that sounds like natural speech even though it’s not dialogue.

Here’s a lovely example from Blake Crouch’s Recursion (p. 182).

|

There's a part of him that wants to run down there, charge through, and shoot every fucking person he sees inside that hotel, ending with the man who put him in the chair. Meghan’s brain broke because of him. She is dead because of him. Hotel Memory needs to end.

But that would most likely only get him killed. No, he'll call Gwen instead, propose an off-the-books, under-the-radar op with a handful of SWAT colleagues. If she insists, he'll take an affidavit to a judge. |

Notice how the narration style is third person, though it doesn’t feel like it. Instead, we’re right inside the viewpoint character’s head.

The position of the conjunction in this example isn’t the sole reason why the narrative distance feels short – the free indirect speech above and beneath plays a huge part – but it certainly helps to give us a sense of the character’s mentally working out a problem.

Introducing tension and suspense

Take a look at this excerpt from p. 21 of The Matlock Paper by Robert Ludlum.

|

Matlock walked to the small, rectangular window with the wire-enclosed glass. The police station was at the south end of the town of Carlyle, about a half a mile from the campus, the section of town considered industrialized. Still, there were trees along the streets. Carlyle was a very clean town, a neat town. The trees by the station house were pruned and shaped.

And Carlyle was also something else. |

With that one word – the conjunction – Ludlum stops us in our tracks. Yes, we’re thinking, the town’s neat, it’s clean. All well and good. But then we realize that there’s more to it, for beneath the pruned trees lies a dark underbelly.

The ‘And’, positioned right up front, forces us to pay attention to it. It’s not any old conjunction. Rather, it’s loaded with suspense that drives the reader to ask a question that isn’t explicitly answered: What else is that ‘something’?

Adding drama and modifying rhythm

In this excerpt from Parting Shot (p. 433), the author uses the conjunction at the beginning of the sentence to inject drama into a scene.

The new line makes the rhythm of the prose more staccato, but the ‘And’ at the beginning of the final line is what really packs a punch.

The viewpoint character, Cory, is a killer. He ponders almost matter-of-factly who the threats are, and reaches his conclusion as he closes in on the cabin.

|

Dolly Guntner certainly wasn't in a position to say anything bad about him.

Which left Carol Beakman. Carol had seen him. And while she didn't actually see him kill Dolly, if the police ever spoke with her, she'd be able to tell them it couldn't have been anyone else but him. As far as Cory could figure, the only living witness to his crimes was Carol Beakman. He was nearly back to the cabin. It seemed clear what he had to do. And he'd have to do it fast. |

If Linwood Barclay had omitted the conjunction, he’d have introduced a separation between two ideas: realizing what needs to be done, and when the killer is going to do it. Yet these two ideas are very much connected. The ‘And’ therefore fulfils its purpose as a conjunction – a joining word.

But there’s more. If he’d run the two ideas together with a conjunction between (‘It seemed clear what he had to do, and he'd have to do it fast.’), the line would have lost its wallop. The staccato rhythm (one that mirrors the cold calculation taking place in Cory’s head) is gone. Instead, the prose has flatlined; it seems almost mundane, like a stroll in the park rather than the planning of a murder.

However, the ‘And’ reinforces this extra information – the deed must be done fast. The emphasis adds drama to the line. The final line is still connected to the clause it’s related to, but the mood-rich rhythm, and the drama that comes with it, is intact.

Emphasizing the unexpected

An up-front ‘But’ is perfect for the author who want to emphasize the unexpected, surprise or absurdity. Take a look at this excerpt from Terry Pratchett’s Dodger (p. 170).

It’s true that omitting the ‘But’ would leave the meaning intact. However, adding the conjunction reinforces the Dodger’s emotional response to the boy’s suggestion – he’s taken by surprise because in times past, asking a peeler was exactly what he’d have done, without question, without fear.

And so that ‘But’ does more than act as a conjunction. With just three letters, we’re shown character mood.

Making contrast explicit and suspenseful

David Rosenfelt’s New Tricks (p. 92) includes a smashing example how the conjunction at the beginning of the sentence reinforces a contrast with what’s gone before.

|

I won't be able to place this in any kind of context until I go through everything Sam has brought, though he says he didn't see a reply to Jacoby's questions. Certainly the fact that a man who was soon to be a murder victim experimenting in any way with his own DNA is at least curious, and something for me to look into carefully if I stay on the case.

But a nurse comes in and asks me to quickly come to Laurie's room, so right now everything else is going to have to wait. |

That contrast is explicit because the ‘But’ acts as an interrupter. We’re deep in the POV character’s head regarding the murder victim, ruminating with our protagonist. The conjunction then shoves us out of that rumination. It’s not gentle; the ‘But’ is a big one – something’s up with Laurie.

Not that we know what. Rosenfelt doesn’t tell us yet. Instead, he makes us ask the question: Why? And with that question, just as with the Ludlum example above, we have suspense.

Summing up

Feel free to pepper your prose with sentences that begin with ‘And’ and ‘But’. Anyone who tells you you’re on shaky ground grammatically knows less about grammar than you do!

It’s likely that the myth around positioning these conjunctions came about in a bid to nudge people away from stringing together clauses and sentences with no thought to creativity. And while such an intention makes sense, we have to recognize that imposing this zombie rule on writing can actually destroy the magic of prose.

And on that note, I will sign off! (See what I did there?)

More fiction editing guidance

- 3 reasons to use free indirect speech

- Author resources library: Booklets, videos, podcasts and articles for authors

- Commas, conjunctions and rhythm

- Coordinating conjunctions

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level: My flagship line-editing book

- How to write suspenseful chapter endings

- Rules versus preferences

- Sentence length, pace and tension

- Switching to Fiction: Course for new fiction editors

- Transform Your Fiction guides: My fiction editing series for editors and authors

Cited sources

- At Risk, Stella Rimington, Arrow Books, 2004

- Don’t Let Go, Harlan Coben, Arrow Books, 2017

- Dodger, Terry Pratchett, Corgi, 2012

- Recursion, Blake Crouch, Pan Macmillan, 2019

- The Matlock Paper, Robert Ludlum, Orion, 2010

- The Dream Archipelago, Christopher Priest, Gollancz, 2009

- Parting Shot, Linwood Barclay, Orion, 2017

- New Tricks, David Rosenfelt, Grand Central Publishing, 2009

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Common examples are:

- there are/is/was/were

- it is/was

Take a look at the following pair. The first sentence is introduced by an expletive.

- There was a car parked outside the house.

- A car was parked outside the house.

When used well, expletives are enrichment tools that allow an author to play with a narrative voice’s register and the rhythm of sentences.

When prose is overloaded with them, it can feel cluttered with filler words that add nothing but ink on the page. At best, they widen the narrative distance between the reader and the POV character; at worst, they flatten a sentence and destroy suspense and tension.

Too much telling of what there is or was can rip the immediacy from a scene and encourage skimming. That’s a problem – it means the reader isn’t engaged and risks missing something.

Furthermore, if they’re not performing their rhythmic or emphasis role, expletives make sentence navigation more difficult because all they're doing is cluttering the prose.

Here's an example. Think I've overworked it? There are published books from mainstream presses with passages just like this made-up one.

It was a tiny room. There was a light switch with rust-coloured smudged fingermarks on the melamine surface. Was that blood? There was a noise coming from beyond on the back wall. It was a high-pitched whimper. Then there was silence. She held her breath and tiptoed forward.

Suddenly there was a scream.

The problem with the expletives in the passage above is that readers are bogged down in what there was rather than the viewpoint character's experience of discovery. Let's revise it to fix the problem.

The room was tiny. Rust-coloured fingermarks smudged the melamine surface of the light switch. Blood maybe. A noise came from beyond a door on the back wall. A high-pitched whimper. Then nothing. She held her breath and tiptoed forward.

A scream shattered the silence.

Notice how the narrative distance has been reduced in the revised passage. Now it's as if we're in the viewpoint character's head, moving with her second by second. We can focus on the room, the dried-blood fingermarks, the whimper, and the scream rather than the being of those things – their was-ness.

Removing the expletives and swapping in stronger verbs (smudged, shattered) enables us to tighten up the prose and introduce immediacy. And now there's no need for the told 'suddenly' – we experience the suddenness through the in-the-moment shattering.

As is always the case, obliterating expletives from a novel would be inappropriate because sometimes they're the perfect tool to help out with rhythm and emphasis.

The opening paragraph of Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities (p. 1) uses expletives galore, and masterfully at that. The repetition (anaphora) brings a steady rhythm to the passage that ensures the reader gives equal weight to the contrasting extremes – from best and worst to hope and despair.

The expletives introduce a detached sense of reportage that forces us forward rather than allowing us to dwell on any of the heavens or hells on offer. It’s simultaneously mundane and monstrous, and that's why it's magical.

And here’s an example from Dog Tags (p. 1) where omission of the expletive would rip the energy from the opening first line of the chapter and interfere with our understanding of which words we’re supposed to emphasize.

That was the USA Today headline on a piece that ran about me a couple of months ago.

Summing up

Grammatical expletives are a normal part of language and have every right to be in a novel. Overloading can destroy tension and make for a laboured narrative, but a purposeful peppering can amplify character emotion, moderate rhythm, and make space for the introduction of big themes in small spaces without sensory clutter.

Cited works and further reading

- Author resource library (includes links to free webinars)

- A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens, W. W. Norton & Company; Critical edition, 2020

- Dog Tags, David Rosenfelt, Grand Central Publishing, Reprint edition, 2011

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level: A Guide for Beginner and Developing Writers

- Making Sense of Punctuation: Transform Your Fiction 2

- ‘Playing with sentence length in crime fiction. Is it time to trim the fat?’

- ‘Playing with the rhythm of fiction: commas and conjunctions’

- 'Should I use a comma before coordinating conjunctions and independent clauses in fiction?'

- ‘What is anaphora and how can you use it in fiction writing?’

- 'Why "suddenly" can spoil your crime fiction'

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Point of view (POV) describes whose head we’re in when we read a book ... from whose perspective we discover what’s going on – and the smells, sounds, sights and emotions involved.

Third-person omniscient POV

This viewpoint is probably the trickiest to master. Omniscient means all-knowing. It’s the most flexible because it gives the reader potential access to every character’s external and internal experiences. It also has the potential to be the least intimate if not handled well.

Imagine a futuristic news helicopter. Inside, our roving reporter shifts her camera from one person to another, and one setting to another. She’s also got some serious kit, stuff that enables her to tap everyone’s phones, TVs and computers. But that’s not all; the characters’ brains are bugged too; our reporter knows what they’re thinking. She can see, hear and smell it all! Says Sophie Playle:

Examples: Deeper knowledge than third-person narration

If you’ve read anything by Neil Gaiman, you’ll see a blatant external narrator in evidence with a depth of knowledge that defies the rules of a third-person viewpoint. Here’s an example from Neverwhere (p. 10).

|

He continued, slowly, by a process of osmosis and white knowledge (which is like white noise, only more informative), to comprehend the city, a process which accelerated when he realized that the actual City of London itself was no bigger than a square mile [...]

Two thousand years before, London had been a little Celtic village on the north shore of the Thames which the Romans had encountered and settled in. London had grown, slowly, until, roughly a thousand years later, it met the tiny Royal City of Westminster [...] London grew into something huge and contradictory. It was a good place, and a fine city, but there is a price to be paid for all good places, and a price that all good places have to pay. After a while, Richard found himself taking London for granted. |

The first ten words might appear to be a third-person viewpoint (‘He’ refers to Richard, the protagonist), but that’s not the case. What follows is a distinct narrative other, a voice that explains ‘white knowledge’.

In the second and third paragraphs, the all-knowing narrator offers historical information. Then in the final paragraph, we’re told more about Richard. The viewpoint was never third-person objective. It was omniscient all along.

In Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, ‘the man’ takes centre stage in most of the sections such that we see what he sees and feel what he feels. It’s almost as if he’s the narrator, and once more we could be forgiven for thinking the viewpoint third person. But there’s more going on here.

In the following extracts, notice the shift beyond what it’s possible for the man to see, think or know.

|

He woke in the morning and turned over in the blanket and looked down the road through the trees the way they’d come in time to see the marchers four abreast. Dressed in clothing of every description, all wearing red scarves at their necks. Red or orange, as close to red as they could find. He put his hand on the boy’s head. Shh, he said. (pp. 95–6)

He wallowed into the ground and lay watching across his forearm. An army in tennis shoes, tramping. Carrying three-foot lengths of pipe with leather wrappings. [...] The phalanx following carried spears or lances tasselled with ribbons, the long blades hammered out of trucksprings in some crude forge upcountry. The boy lay with his face in his arms, terrified. (p. 96) |

In the first extract, only an all-knowing alternative narrator could be privy to the intent behind the marchers’ colour choice of scarves. In the second, the man watches the army, but it’s only an omniscient narrator who can know where their blades were forged and how the boy is feeling. Maybe that narrator is McCarthy; maybe it’s someone else. But it’s not the man.

Example: World-building backstory in a flash

Some genres – science fiction and fantasy for example – lend themselves well to omniscient narrators because they can provide critical world-building backstory quickly. Terry Pratchett’s Wyrd Sisters provides a fine example (pp. 1–2).

|

Through the fathomless deeps of space swims the star turtle Great A’Tuin, bearing on its back the four giant elephants who carry on their shoulders the mass of the Discworld. A tiny sun and moon spin around them, on a complicated orbit to induce seasons, so probably nowhere else in the multiverse is it sometimes necessary for an elephant to cock a leg to allow the sun to go past.

Exactly why this should be may never be known. Possibly, the Creator of the universe got bored with all the usual business of axial inclination, albedos and rotational velocities, and decided to have a bit of fun for once. |

What omniscient is not

An omniscient viewpoint can be powerful but it needs to be controlled and used with purpose. If we’re accessing one character’s thoughts and experiences, and we jump to another character’s viewpoint, it can jar the reader. That's called head-hopping.

Imagine you’re listening to your best friend tell you about a difficult experience. Even though it didn’t happen to you, her description of the event helps you to imagine the challenges she faced, the emotions she grappled with. You’re thoroughly immersed and emotionally connected.

Then someone else barges up to you both and tells you what it was like for them. Your friend butts back in to wrestle the telling back to her.

Would the interruption annoy and frustrate you? Would you feel like your efforts to invest in your friend’s story were being thwarted?

The impact is the same when it occurs in a book’s narrative (though not the dialogue, of course). That viewpoint ping pong is not omniscient POV. It’s third-person limited gone awry.

Recommendation

I recommend caution. The beauty of fiction often lies in the unveiling, in the immersion. Overuse of an omniscient narrator can block this.

The all-seeing eye can be a powerful tool – as demonstrated by the examples above – but less experienced authors, particularly those writing commercial fiction such as thrillers and mysteries, risk accidental head-hopping, which will destroy the tension and distance the reader from the characters.

Cited sources and related reading

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level, Louise Harnby, Panx Press, 2020

- Making Sense of Point of View (Transform Your Fiction series: 1), Louise Harnby, Panx Press, 2020

- Neverwhere, Neil Gaiman, William Morrow Paperbacks, reprint edition, 2016

- Resources for authors: Library of articles, podcasts, videos and booklets for independent writers

- The Road, Cormac McCarthy, Picador, 2009

- 'What’s the Difference Between Omniscient and Third Person Narration?' Sophie Playle, Liminal Pages

- 'What is head-hopping?'

- Wyrd Sisters, Terry Pratchett, Harper, reprint edition, 2013

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

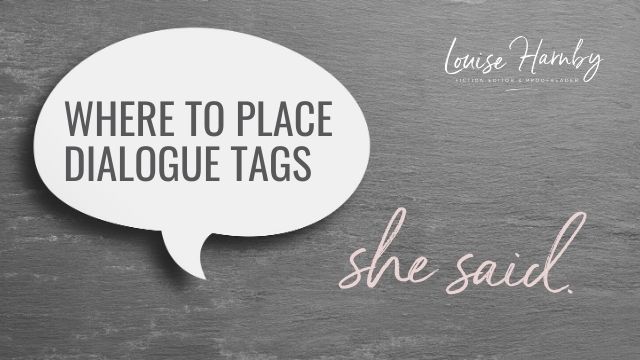

Dialogue tags, or speech tags, are complementary short phrases that tell the reader who’s talking. They’re not always necessary, particularly if there are only two speakers in a scene, but when they are used, this is what they look like:

- ‘Dump that corpse and don’t ever mention it again,’ the hooded guy whispered.

- “Thanks for holding the gun,” Tom said. “Now pull the trigger.”

- Marg turned. Smirked. Said, ‘Tomorrow. If you’re late, he’s late. Geddit?’

Said is often best because readers are so used to seeing it that it’s pretty much invisible and therefore less interruptive.

What’s the rule about where tags go?

Dialogue tags can be placed after, between or before dialogue. Authors sometimes ask which position is best or whether there’s a rule.

There is no rule. All three positions have advantages and disadvantages, depending on what you want to achieve.

Position: After dialogue

Readers are so used to seeing speech tags like said at the end of dialogue that they’re almost invisible. That allows the dialogue, rather than the speaking of the dialogue, to be the focus.

Below is a wee example from Recursion (p. 292). The speech takes centre stage; the doing of speech (screaming, in this case) comes afterwards.

Furthermore, when the tag comes after the dialogue, it can roll seamlessly into any supporting narrative, as shown in the example from The Ghost Fields (p. 194).

|

“Come on!” he screams.

‘It’s very … evocative,’ says Ruth. This is true. The brushwork may be crude, the planes out of perspective and the figures barely more than stick men, but there’s something about the work of the unknown airman that brings back the past more effectively than any documentary or reconstruction. |

There are a couple of potential disadvantages:

- In longer chunks of dialogue in scenes with more than two speakers, the reader will have to wait until the end of the speech to find out who’s saying what.

- Placement at the end of speech can flatten a one-liner or suspense point in dialogue.

Position: Between dialogue

Placing speech tags between dialogue is also common and unlikely to jar the reader. Here are three reasons why it works:

- The tag breaks up longer streams of dialogue, which is especially handy if a monologue’s rearing its head.

- We’re given an early indication who’s speaking. If there are more than two speakers in a scene, and the reader’s likely to be confused, placement between the speech is an effective solution.

- One-liners, suspense points and shocks get to take centre stage. Adding the speech tag at the end could flatten the tension.

Here are two examples in which the mid placement of the tag means the suspense isn't interfered with. The first is taken from The Ghost Fields (p. 194); the second is something I made up.

In the second example, rejig the sentence so that Tom said comes after all the speech, and notice how this makes the wallop vanish from the line about pulling the trigger.

Position: Before dialogue

Placement of the tag before the dialogue isn’t a no-no but it is a less common option and more noticeable.

A tag tells of speaking; dialogue shows character voice, mood and intention. When the speaker’s announced first, it’s a tap on the shoulder that draws attention to speaking being done. It expands what author and creative-writing expert Emma Darwin calls the ‘psychic distance’ between the reader and the speaker, which can flatten the mood.

And, yet, this can also be its advantage. That tap introduces a more staccato rhythm that can stop a reader in their tracks.

In this extract from Recursion (p. 292), the placement of the tag before the dialogue induces an acute sense of resignation – that dull thump in the pit of one’s stomach when the proverbial’s hit the fan.

Not placing tags: Omission

There’s no need to include a speech tag if it’s adding nothing but clutter. In the following example from Recursion (p. 125), the author has omitted them because there are only two speakers. He lets the dialogue, and its punctuation, inject the voice, mood and intention into the scene rather than telling us who’s speaking and how they’re saying it.

Summing up

Placement of dialogue tags isn’t about rules. It’s about purpose:

- Varying rhythm

- Respecting mood and suspense

- Clarifying who’s speaking

- Avoiding unnecessary clutter

For that reason, mixing up the position of speech tags can be effective.

Let’s end with an extract from Out of Sight (pp. 135–7), which demonstrates the varied ways in which author Elmore Leonard handles his tagging: beginning, between, end, and omission.

|

‘But you think they’re coming back,’ Karen said.

‘Yes, indeed, and we gonna have a surprise party. I want you to take a radio, go down to the lobby and hang out with the folks. You see Foley and this guy Bragg, what do you do?’ ‘Call and tell you.’ ‘And you let them come up. You understand? You don’t try to make the bust yourself.’ Burdon slipping back into his official mode. Karen said, ‘What if they see me?’ ‘You don’t let that happen,’ Burdon said. ‘I want them upstairs.’ |

Cited sources and further reading

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level, Louise Harnby, Panx Press, 2020

- How to Punctuate Dialogue (free webinar)

- Out of Sight, Elmore Leonard, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2017

- Recursion, Blake Crouch, Pan, 2020

- The Ghost Fields, Elly Griffiths, Quercus, 2015

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Point of view (POV) describes whose head we’re in when we read a book ... from whose perspective we discover what’s going on – and the smells, sounds, sights and emotions involved.

There can be multiple viewpoints in a book, not all of which have to belong to a single character. Plus, editors’ and authors’ opinions differ as to which approach works best, and what jars and why.

My aim is to keep the guidance as straightforward as possible, not because I think you should only do it this way or that way, but because most people (myself included) handle complexity best when they start with the foundations.

Second-person narrative viewpoint

In second-person narrative POVs, the pronoun is ‘you’. This narration is intimate, but strangely so, as if the author is talking directly to the reader as a character.

That intrusive element is both its strength and its weakness. It’s powerful because it places readers at the heart of the story, and yet we – the ‘you’ – know less than the narrator.

That can create a sense of immediacy, but almost amnesiac dislocation. We have to discover what we think, see, know and do. And if we don’t identify with the ‘you’ – if we feel implicated rather than attached – we can be pulled out of the story rather than brought deeper into it.

Still, this controlling aspect of second person can have an advantage. Whereas first-person narrators tell you what they thought and did, second-person narrators tell us what we thought and did.

This witnessing adds a level of reliability (even if we don’t like it). And readers aren’t daft. They know they’re not really the you-character, which means authors could use it as a tool to create surprise when the ‘you’ is unveiled later in the book.

If you want your readers to feel connected but controlled, second-person POV might be just the ticket, but it’s difficult to pull off and rare that authors of contemporary commercial fiction write an entire novel in it (though check out Half Asleep in Frog Pajamas by Tom Robbins if you want to see a good example in action).

More likely, you’ll see shorter-form use: dedicated chapters or other narrative forms such as diary entries, letters or other missives.

In this example from Complicity (p. 9), Iain Banks uses the second-person viewpoint in which a narrator reports on the actions and thoughts of an unnamed serial killer addressed as ‘you’.

|

There is another faint crunching noise as the body spasms once and then goes limp. Blood spreads blackly from his mouth over the collar of his white shirt and starts to drip onto the pale marble of the steps. [...]

You go downstairs and walk through the kitchen, where the two women sit tied to their chairs; you leave via the same window you entered by, walking calmly through the small back garden into the mews where the motorbiked is parked. You hear the first faint, distant screams just as you take the bike’s key from your pocket. You feel suddenly elated. You’re glad you didn’t have to hurt the women. |

Think about how you feel as you read this. It’s as if you’re being addressed, as if you’re complicit. At the very least, the prose arouses curiosity – who is this ‘you’, and how is it that the narrator knows so much about them?

Banks doesn’t present the novel fully in second person; these sections fall between those of a first-person viewpoint character, journalist Cameron Colley. As such, readers are confronted by a juxtaposition of Cameron’s version of events and what was witnessed by the narrator.

Recommendation

By all means, experiment with second-person point of view but understand its implications. If you want to draw your reader into the heart of your story, it’s a good choice. However, that connection can come at a price – a lack of control that could alienate your audience.

For that reason, consider the purpose of this narrative style and the extent to which you employ it. It might be better constrained – limited to chapters inhabited by specific viewpoint characters.

If in doubt, rewrite your scene in an alternative narrative viewpoint so you can evaluate how this affects your perception of the story as a reader.

|

Cited sources and related reading

|

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Listen to find out more about:

- Being a Hollywood camera operator ... Jurassic Park, Thelma and Louise, and NYPD Blue

- Getting a publishing contract with a major press

- The Mason Collins series

- When publishers are no longer invested

- Moving to independent publishing

- Clawing back book rights

- Using movie experience to craft a novel's scene

- Beyond writing: what indie publishers need to do

- Challenges and benefits of indie publishing

- Being edited

- Useful organizations

- Writing a series versus standalone novels

- Future projects

Top tips From John

- Build a mailing list

- Offer a free short story or novella

- Develop a series

- Use Facebook ads

- Craft a great website

- Engage with your audience

- Get your business head on

- Invest in appropriate editing

Contact John A. Connell

Subscribe to John's newsletter and get a free book:

- Website: John A Connell: Gripping Thrillers With a Historical Twist

- Email: [email protected]

- Facebook author page

- John's books on Amazon US and UK

Editing bites

- Stephen King (video): Masterclass, University of Massachusetts Lowell, 2012

- Joanna Penn: Video marketing for authors

- Mark Dawson's Self-Publishing Formula

- International Thriller Writers

- Mystery Writers of America

- Mark Dawson's Self-Publishing Formula

Ask us a question

The easiest way to ping us a question is via Facebook Messenger: Visit the podcast's Facebook page and click on the SEND MESSAGE button.

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Listen to find out more about:

- Fiction versus non-fiction

- The type of editing

- Subject/genre

Editing bites and other resources

- Storycraft: The Complete Guide to Writing Narrative Nonfiction (Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing, and Publishing), Jack Hart

- ‘The Secrets of Story Structure’, KM Weiland

- The Editing Podcast, S1E1: The different levels of editing

- Switching to Fiction (online course for aspiring fiction editors)

- Research tools for crime and thriller writers (blog post)

- Consulting Cops

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Listen to find out more about:

- ALLi blog: Alliance of Independent Authors

- Ann Handley blog

- Articles: The Writer’s Digest

- Articles: Tim Storm, Storm Writing School

- Bacon Editing blog: Claire Bacon

- Bookbaby blog

- Clarity: Lisa Poisso, Editor and Book Coach

- Denise Cowle Editorial Services blog: Denise Cowle

- Helping Writers become Authors: KM Weiland

- Jane Friedman blog

- LibroEditing blog: Liz Dexter

- Liminal Pages blog: Sophie Playle, Fiction Editor

- The Creative Penn blog: Joanna Penn

- The Editor’s Blog: Beth Hill

- The Itch of Writing: Emma Darwin

- The Editing Blog: Louise Harnby, Fiction Editor

- The Radical Copyeditor blog: Alex Kapitan

- The Subversive Copyeditor blog: Carol Saller

Editing bites and other resources

- Cult Pens

- Stein on Writing, by Sol Stein, Non Basic Stock Line, 2007

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Point of view (POV) describes whose head we’re in when we read a book ... from whose perspective we discover what’s going on – and the smells, sounds, sights and emotions involved.

Third-person limited POV

Along with third-person objective, this viewpoint is the one that most writers find easiest to master at the beginning of their journey. Furthermore, readers are used to encountering it in contemporary fiction. The pronouns of choice are ‘she’, ‘he’, ‘it’ and ‘they’.

Third-person limited is so called because it’s a deeper viewpoint that limits readers to a single character’s experience – what they see, hear, feel and think. Readers get to sit in their skin and that provides an immersive experience. It’s as if we’re them.

Example: Intimacy and getting under the character’s skin

Here are some examples from Mick Herron, Harry Brett and Louise Penny that demonstrate an intimate third-person limited narrative:

|

For almost a minute that was that. Shirley could feel her watch ticking; could feel through the desk’s surface the computer struggling to return to life. Two pairs of feet tracked downstairs. Harper and Guy. She wondered where they were off to. (Dead Lions, p. 17)

His mum pushed past him, bringing a cloud of thick night air seasoned with salt and something he couldn’t place. A perfume perhaps, but not his mother’s normal scent. (Time to Win, p. 321) The blurred figures at the far end of the long corridor seemed almost liquid, or smoke. There, but insubstantial. Fleeting. Fleeing. As she wished she could. This was it. The end of the journey. Not just that day’s journey as she and her husband, Peter, had driven from their little Québec village to the Musée d’Art Contemporain in Montréal, a place they knew well. Intimately. (A Trick of the Light, pp. 1–2) |

The voices are distinctive. It’s not just dialogue that conveys how the viewpoint characters speak and think; it’s the narrative too.

However, it’s called third-person limited for a reason. Strictly speaking, what that character can’t see or know shouldn’t be reported. In the above examples, we’re left with questions – of destination in the first, of the origin of a smell in the second, and of the nature of the journey – because we don’t know any more than the viewpoint characters.

Third-person limited is effective because an author doesn’t want to give everything away at once. The limitations over what can be known, and therefore divulged, allow the writer to control the unveiling of information via the viewpoint character.

Recommendation

I recommend you stick to a single character’s POV per chapter or section to avoid confusion or interruption. Mittelmark and Newman (p. 159) offer this wisdom:

That’s worth heeding. It means the reader’s trust has been lost, that they’ve been pulled out of the story rather than drawn further into it.

Trickier still is narrative ping pong, where within one section we bounce back and forth between the POVs of Character X and Character Y.

Here’s a made-up example that demonstrates how things can go wrong.

‘You okay, Jan?’ said Melody. She’d barely got the words out – her throat was on fire. All she wanted to do was stop, breathe, devour that bottle of water in her backpack bouncing hard against her spine.

‘We’re here,’ Jan said. Thank God. Tears of relief stung her eyes. She’d been worried Mel wouldn’t keep up. Guilt niggled. Would she have gone back for her? She wasn’t sure.

The problem with this kind of setup is that it ‘alienates the reader from both perspectives. She is unable to identify with either because there’s no telling when it will be yanked away’ (Mittelmark and Newman, p. 161).

In other words, the reader has been prevented from immersing themselves in the character’s version of the story. When you stay in the head of one character per chapter or section, you make your writing life and your reader’s journey easier.

Third-person objective POV

If third-person limited provides intimacy – allowing us to explore a character’s emotions and hear their voice – third-person objective offers a more neutral flexibility when we need some distance to look around and beyond objectively.

Like its limited sister, writers find this easiest to master and readers are used to encountering it. The pronouns too are ‘she’, ‘he’, ‘it’ and ‘they’.

It’s a useful viewpoint for the author who wants to convey descriptive information – height, weight, facial expression, environment. If you’re using this POV, practice your observation skills so that you understand how people move from place to place, what they wear, where they live, how they gesture, so that you can show what might be going on in their heads through what can be observed.

The same can be said of the objects in your novel. How does light play on water or a brick building at various times of the day? What sounds might be audible in your environment? How do the seasons affect the flora and fauna?

Third-person objective viewpoints are powerful because they force a writer to show rather than tell what’s being seen. That’s because we don’t have access to the internal thoughts of a character.

Example: A more distant and descriptive narrative

Here’s an example from David Baldacci’s The Fix (p. 3) that demonstrates third-person narration as observable description.

|

Amos Decker trudged along alone. He was six-five and built like the football player he had once been. He’d been on a diet for several months now and had dropped a chunk of weight, but he could stand to lose quite a bit more. He was dressed in khaki pants stained at the cuff and a long, rumpled Ohio State Buckeyes pullover that concealed both his belly and the Glock 41 Gen4 pistol riding in a belt holster on his waistband.

|

Example: Shown-not-told in action

Here are some excerpts from Stephen King’s The Stand that demonstrate a close attention to the way things and people behave when observed.

|

The Chevy jumped like an old dog that had been kicked and plowed away the hi-test pump. It snapped off and rolled away, spilling a few dribbles of gas. The nozzle came unhooked and lay glittering under the fluorescents. (p. 8)

“Clock went red,” the man on the floor grunted, and then began to cough, racking chainlike explosions that send heavy mucus spraying from his mouth in long and ropy splatters. Hap leaned backward, grimacing desperately. (p. 11) She walked softly up behind him and laid both hands on his shoulders. Jess, who had been holding his rocks in his left hand and plunking them into Mother Atlantic with his right, let out a scream and lurched to hit feet. Pebbles scattered everywhere, and he almost knocked Frannie off the side and into the water. He almost went in himself, head first. (p. 16) |

Objectivity allows the writer to explore in detail what would be unnatural for a character to report directly. Remember, we’re not accessing thoughts, opinions and emotions with an objective POV, just the stuff that any onlooker could see, hear or smell.

Objective is the key word here. Third-person objective viewpoints should focus on what could be known by a narrator witnessing that scene. When information is reported that moves beyond a floating camera that’s tracking the immediate environs and into a space where the narrator knows more than could possibly be witnessed by the character or the onlooker, omniscience is in play (more on that below).

In some genres – crime fiction for example – this can be useful because the reader will be forced to reach their own conclusions as to the reasons for, or motivations behind, a particular event or behaviour. In other words, it’s mysterious.

However, it can be distancing if overused and as a result contemporary commercial fiction writers rarely write entire novels from an objective POV because it’s reportage and we can’t get into the characters’ heads. It’s harder to understand what motivates them unless they express it through dialogue. A blend of limited and objective is a more likely choice.

Recommendation

Use third-person objective POV to create suspense, to make your reader wonder, and ask their own questions, and to provide scene-setting information, but blend with a limited viewpoint for deeper emotional engagement.

In the first paragraph of the example below, Baldacci (The Fix, p. 3) uses third-person objective to give us background facts. In the second, he switches to limited to explain the character’s feelings. It’s a lovely fusion:

|

His size fourteen shoes hit the pavement with noisy splats. His hair was, to put it kindly, dishevelled. Decker worked at the FBI on a joint task force. He was on his way to a meeting at the Hoover Building.

He was not looking forward to it. He sensed that a change was coming, and Decker did not like change. He’d experienced enough of it in the last two years to last him a lifetime. He had just settled into a new routine with the FBI and he wanted to keep it that way. |

Cited sources and related reading

- A Trick of the Light, Louise Penny, Three Pines Creations, 2011

- How Not to Write a Novel, Howard Mittelmark and Sandra Newman, Penguin, 2009

- The Fix, David Baldacci, Pan Books, 2017

- The Stand, Stephen King, First Anchor Books, mass-market edition, 2011

- What is a first-person narrative point of view?

- What is a second-person narrative point of view?

- What is an omniscient narrative point of view?

-

What is head-hopping?

- Making Sense of Point of View (Transform Your Fiction series: 1)

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

The impact of ‘before’ and ‘after’ in fiction writing: Tacit and explicit chronology of action

17/2/2020

Here’s what to look out for and how to fix the problem.

Why writers include ‘before’ and ‘after’

The inclusion of ‘before’ and ‘after’ to tell the order of play is not an indication of poor grammar – not at all. There’s nothing grammatically wrong with these constructions.

It’s also why writers sometimes use several adjectives with similar meanings rather than one strong one, or an adverbial phrase to fortify a weak verb.

Some authors also fear that their writing will come across as too ‘plain’ or ‘simple’. Chronological nudges are an attempt to ornament the prose.

Tacit chronology of action

The things that we do occur in a sequence; they have a chronology. This is as much the case in real life as it is on the screen, in an audiobook and in the pages of a novel. That chronology is tacit – we don’t need to explain it because it’s understood.

Take a look at this excerpt from The Devil’s Dice by Roz Watkins (p. 79, HQ, 2019):

Watkins doesn’t tell us explicitly that the shuddering occurred before the laptop was put down, or that the laptop was moved before the character shifted the cat onto their knee. And yet we know. The sequence of events is implied by the order in which she places each clause. It’s tacit.

- First thing that happens: shudders

- Next thing that happens: moves laptop

- Next thing that happens: manoeuvres cat

- Next thing that happens: leans

- Next thing that happens: inhales cat odour

And that’s the thing with strong line craft – it allows the reader to immerse themselves in the chronology of action by showing us, clause by clause, what’s transpiring, instead of tapping us on the shoulder and telling us.

Explicit chronology of action

Let’s recast the Watkins excerpt with some explicit taps on the shoulder:

I see this use of timeline nudges frequently in the fiction writing of less experienced authors, and it’s problematic when overused. Here’s why.

1. Some readers might feel patronized

Not every reader will notice the use of chronology nudges. But some will, and since no author wants to alienate a chunk of their readership, why push the story over a cliff when we can work out the sequence of events from the order of the words?

Telling readers that X was done before doing Y, or after doing Z, is akin to saying: ‘Hey, just in case you’re not clever enough, let me spell it out for you.’

It’s a dumbing-down that readers in the know won’t appreciate.

2. The inclusion is unnecessary

If you’re still not convinced, ask yourself whether the inclusion of ‘before’ or ‘after’ as timeline nudges is necessary. It often isn’t.

If a character’s shuddering occurs at the beginning of a sentence, the reader will assume that shuddering is what’s happening right now. If a new action follows that shuddering, the reader will assume that – just like in real life – the moment has passed and something else is happening in the new now of the novel.

3. The reader is focused on the wrong thing

When writers create immersive fiction, the reader feels as if they are in the moment – this is happening, now that, now the other.

‘Before’ and ‘after’ are distractions that focus the reader on when rather than what’s happening. The former is telling; the latter is showing.

4. There are more words than are necessary

Not enough words leaves readers hungry for clarity. Too many gives them indigestion. The artistry comes in the form of balance.

As long as the sequence of events can be understood by the reader, consider whether timeline nudges such as ‘before’ and ‘after’ are cluttering your prose.

Take a look at these pairs of narrative text, each of which has a shown tacit chronology and an alternative told explicit sequence. Which versions are more suspenseful? Which are most immediate? Which flow better when you read them out loud?

I’ve used examples from published fiction for the tacit versions, and taken a little artistic licence – altering them in ways their authors never intended – for the explicit chronologies.

In the original version, the ‘and’ between the initial breath and the walk into the kitchen is a fine example of the power of a conjunction. It’s almost invisible, which gives us the space to take that breath with the viewpoint character. And having taken it, we’re ready to go into the kitchen with them.

In the edited version, ‘before’ pulls us away from that moment. The tension has fallen out of the sentence.

|

The Dream Archipelago, Christopher Priest, Gollancz, 2009, p. 201

|

In the original version, it’s as if we’re in the room, watching the man as he smiles and leans back. There is space for that action to have its moment. Then he blows the smoke – that’s the new moment; we’ve left the other behind.

In the edited version, ‘after’ shoves us past the leaning back and smiling before we’ve had a chance to savour it. It’s already gone, even though we’re still reading about it.

|

Jurassic Park, Michael Crichton, Arrow, 2006, Prologue from Kindle edition

|

In the original version, Crichton shows us the action. Perhaps, like me, you can hear the chunter of the helicopter blades in the air. Who’s in this helicopter? Men in uniform. They jump out. What will happen next? We’re shown: they fling open the door. There’s a sense of order, of clandestine and militaristic precision.