|

Online writing courses

Just a quickie ... a member of Louise's Writing Library asked me if I'd put together a list of online writing courses. It's a work in progress and I'll be adding new resources as I become aware of them. If you think I've missed something, drop me a line at [email protected]. You can access the current list via the Self-publishers page on my site, where all the library resources live. Just look for Online Tutoring for Self-Publishers: Writing Courses and click on the image to download the free PDF. Until next time ...

Louise Harnby is a fiction copyeditor and proofreader. She curates The Proofreader's Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. If you're an author, you might like to visit Louise’s Writing Library to access my latest self-publishing resources, all of which are free and available instantly.

0 Comments

Abigail is based in the UK and has been proofreading and editing for around five years. Most of her work thus far has come via existing contacts, personal referrals, and a third-party site.

Until recently, that was sufficient. Consequently, she hasn’t spent any time thinking about a website, marketing, or other forms of outreach. Furthermore, the third-party site has changed the service-fee structure so that the work is no longer as lucrative.

She asks: ‘At the moment, I do a lot of academic work, which I love and would like to continue; I just want to secure it privately rather than through third-party sites. In addition, I would like to move away from website copy, blog posts and more generalised proofreading, and start working with publishers on longer and more interesting projects. However, I don’t know where to start, what’s required, or how to approach them. Many thanks for any guidance you can provide!’ Thanks for your question, Abigail! So, something else you mentioned in your email to me is that you’re undergoing professional training. I was really pleased to hear this because I think it’s an essential element in the mainstream publishing market. I’m going to focus on the following:

Why targeting publishers is such a good step Publishers are still the preferred client group for many editorial freelancers. There are several reasons for this:

A quick note on earnings and work stream There’s a lot of talk in the online international editorial community about publishers and low fees. The situation is not straightforward. There is no universal fee for copyediting or proofreading. I rarely work for publishers these days, but when I did I was offered proofreading fees from academic presses that worked out as low as £10 per hour and as high as £40 per hour. It depends on the complexity of the project, the press, the brief, the length, the number of authors, and a ton of other things. After you’ve done a few projects for a publisher, you’ll start to get a sense of how things work and what you can expect to earn on average. Some publishers will offer you a fee of £X per hour, and a guideline for the number of hours they expect the project to be completed in. Some will offer a flat fee for the job. Some of my colleagues (like Liz Jones: see her excellent post in Further reading, below) have successfully negotiated fees when they encountered scope creep. With some presses, I found that I could counter what seemed initially to be a less favourable fee by being as efficient as possible. You’ll also speed up as you become more familiar with a press – their house style, the format of their books, and their preferred professional style manuals and reference systems. Regardless of their fee structure, they do all the project-acquisition work for you, which means you can sit back and focus on the proofreading and editing rather than worrying that your Google Search rankings aren’t as high as you’d like!

Training for academic publishers – what you need to know

In order to ensure you’re fit for purpose with publishers, ask them which style guides and reference systems they prefer, and take time to familiarize yourself with these manuals. Most presses will provide you with a summary of their preferences. Your training course should draw attention to the importance of following a brief. Publishers are usually rigid when it comes to scope, and going beyond the brief without querying first could have detrimental consequences. For example, if you’re training to proofread, you’ll need to practise when to change, when to query and when to leave well enough alone – no in-house editor will thank you for recasting sentences to improve the flow in a proofread. That’s because: it’s expensive to make extensive changes on page proofs; the pagination could be affected; cross-references might be impacted; and the index could be damaged if it’s being created simultaneously. Also check that the training course you’re doing is recognized by the UK publishing industry. You won’t go wrong with the following organizations, though they’re by no means the only ones to consider: Certainly, if you want to proofread for publishers, you’ll need to be familiar with the industry-recognized proof-correction markup language (BS 5261C: 2005). Even if a publisher asks you to proofread on PDF, you might be required (or find it efficient) to use digital versions of these marks. Where academic publishers search Some publishers do search for editors and proofreaders. The SfEP’s Directory of Editorial Services is one port of call. Some also attend the SfEP’s annual conference and the London Book Fair, so those two events are worthy networking opportunities to put yourself on the radar of academic presses. Recently, I was contacted by a publisher via Reedsy. It’s the first time I’ve received a request to quote from a press via this platform, and it was for a fiction title, so I’m not convinced that this would necessarily be a primary channel for you if you want to acquire academic work, but I’m mentioning it just as food for thought. Why going direct is still your best bet My top tip for getting in front of publishers is to contact them direct, by email, phone or letter. The reason why many don’t search online for editorial freelancers is simply because they don’t need to. Build a list of UK academic publishers, then find out the name of the person in charge of hiring – it’s probably someone in the production department – and get in touch with them. You already have lots of experience, and you’ll have a top-notch training course under your belt. I recommend customizing your CV and cover letter/email for each press so that your portfolio of projects sells you as a perfect fit. Read Philip Stirups’ article for more top tips (see Further reading). Don’t put all your eggs in one basket I recommend you build a bank of around ten publishers. If you stick to one or two you could end up in deep water further down the road. If one of those clients were to merge with another, you might fall off the freelance list during the transition. If your other client were to go bust, you’d be scuppered. Having a larger bank of publishers means you have a safety net. It’s likely your publisher client base will grow exponentially; each time you acquire a new client you’ll be more likely to impress another. It’s a small world, and many of the in-house staff know each other. That will work in your favour. Taking academic publishers’ tests Some publishers will ask you to take a test. There are two articles in the Further reading section that offer excellent overviews of how to approach these: ‘The Business of Editing: Editing Tests’ by Rich Adin, and ‘Test Taking Tips For Editors’ by Cassie Armstrong. Asking for testimonials and building a portfolio Are you able to ask current academic clients for testimonials? If so, do so – however embarrassing you find it! This kind of social proof won’t on its own get you work, but it’s one way of demonstrating that you’re capable of fulfilling a client’s brief. I mentioned your portfolio above. If you’ve been in business for five years, chances are you have an amazing project portfolio. Make sure your CV, LinkedIn profile and website reflect your body of completed works. Publishers love to see experience! I hope that brings you a little clarity, Abigail. Good luck with building your new client base! Further reading

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses. Can you become a proofreader even if you have no publishing experience? That's what a reader wanted to know. Here's my answer. Amanda is a UK-based primary-school teacher. She says: ‘I have zero experience in publishing. However, I have a first-class degree in Education Studies and enjoy reading and grammar. I've been reading your blog recently and have thought of qualifying as a proofreader but appreciate how competitive it is. What is the likelihood of me obtaining work based on my background?’ Many thanks for your question, Amanda! So, the short answer is, there’s a strong likelihood if you get your marketing head on. Because, essentially, this is a marketing issue. Here’s my current favourite mantra: We have two jobs: the work we do, and the work we do to get the work we do. In your email to me you talked in terms of ‘qualifying’ so you’re clearly prepared to embark on professional training – a wise decision. It tells me you’re prepared to make yourself fit for practice – the work we do. Now let’s look at what you could do to get that work. 1st-stage marketing (pre-qualification)

These are the basics, but they’re enough to give you a solid set of standard online profiles that represent you and your proofreading business, and that will enable you to connect with like-minded professionals – old hands and new. In reality, your potential client base is rather wide, but I believe that in the start-up phase, when you’re building a proofreading business, it makes sense to target publishers. That’s because:

2nd-stage marketing (post-qualification) So why would a publisher be interested in you, Amanda? Here are some reasons:

And who are those education publishers? Google is your friend here, but here’s a short list of publishers in the UK who have education lists or imprints. In your position, I’d start by getting in touch with every single publisher you can find in the UK who publishes education content.

My bet is that most (many, certainly) academic or scholarly publishers in the UK will have books, journals and electronic products in the field of education at some level. Find out who’s in charge of hiring editorial freelancers. Email or post a cover letter and CV. Be sure to emphasize your training, background, society membership and subject specialisms. In the early stages, education will be your core specialism but, honestly, if you can proofread an educational research book, you can proofread a politics book or a social theory book, so you might decide to expand your list of interests to education, social sciences and humanities. Or you might talk in terms of education teaching, theory, practice, governance, and research, and other key related terms. It’s something to think about. When you start looking at what else all those publishers with education books are putting out to market, you’ll get a sense of how you might customize each contact letter/email so that you really engage with each press’s list. 3rd-stage marketing As you build up your publisher list, your portfolio of completed works, and your testimonials from all those satisfied in-house production editors, you can really start to make your online presence stand out. Perhaps you now meet the criteria to advertise in the SfEP’s online Directory of Editorial Services. This is one way of making yourself visible to clients outside the publishing industry – I’m thinking here of master’s and PhD students preparing dissertations and theses in the field of education and beyond; academics (particularly those whose first language isn’t English) preparing articles for journal submission); independent non-fiction authors, and so on. For a broader look at different marketing approaches, check out the Marketing archive here on the Parlour, or my book Marketing Your Editing & Proofreading Business. If accessing a market outside the mainstream publishing industry is something you’re serious about, start your content marketing as soon as possible. I have a wee primer that will give you the basics. If you want to get serious, visit the Andrew and Pete website. I bang on about these two all the time, but they know their stuff. I wish I’d known them 10 years ago. Unfortunately for me, they’re a fair bit younger so were probably doing their GCSEs when I started my editorial business! But I’m using them now to help me get the very best I can from my marketing. Summing up So, yes, I think you can obtain work if you are practice-fit and ready to plant a big marketing hat on your head and really commit to it! The fact is, it’s noisy out here, and getting noisier. But the market is bigger too – global, in fact – so there’s more competition, but more opportunities too. Another mantra – be interesting and be discoverable.

Get your training and your marketing licked and there’s no reason why you can’t create a successful proofreading business. It will take time and hard graft, but it’s perfectly doable for those with the right mindset. Hope that helps! If you have additional questions, just pop them in the comments below. Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers. She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

I'm so, so grateful to Ray Greenley for taking the time to write a comprehensive primer on audio-book creation for me! It's absolutely brilliant.

Ray's a professional voice artist (he's the narrator behind, among other audio books, Philip K Dick's The Unreconstructed M and Other Stories) but he's a fab writer as well.

I love listening to audio books, but creating them? That’s quite another matter. And yet I wanted to know more, and I figured some of you would too. And because it’s one of those aspects of self-publishing that’s just too expensive to get wrong, I felt that my writing a guide to the process simply wouldn’t do. I wanted to offer you something that would give you in-depth, honest and usable insights. That way, if you do decide to create an audio book, you can do it right. I hoped a professional narrator could furnish you with those insights, and Ray hasn’t disappointed. The following article is an excerpt from the full 26-page primer. At the bottom of the post there's information on how to access Audio-book production: A primer for indie authors from an audio-book producer. Enjoy! (And thank you, Ray!)

An introduction from the voice artist, Ray Greenley

Hello, dear author! Congratulations on your latest book! Have you considered having an audio book of your work produced? If not, you should! More and more consumers are buying audio books for a variety of reasons, and audio-book sales are booming compared to digital print sales (see Resources: Kozlowski). As an author, you absolutely want to be a part of that growing market. But audio books are an entirely different beast from print books. Getting into a new market is always intimidating. Where do you even start? I’m here to help. I’m an audio-book narrator who has worked with indie authors to produce audio-book editions of their work. In Audio-book production I give you a high-level look at what you need to know to get your book produced as an audio book. In this post, we're focusing on platforms and prices. There’s work to be done, but it’s probably not as difficult as you might think. Read on! ‘So how can I get my book produced as an audio book?’ It wasn’t all that long ago that virtually all audio-book production was handled by a few big publishers, and getting your book produced was probably a similar feat to getting a big print publisher to publish and distribute your book. That’s all changed. Getting your book produced as an audio book is easier now than it’s ever been. Probably the biggest factor in that change is a site called ACX. That stands for Audiobook Creation Exchange. It’s run by Audible.com (the world’s largest distributor of audio books, and owned by Amazon.com). It’s essentially a meeting place where rights holders (that’s you!) can list their books in order to find producers (like me!) who are interested in producing the book as an audio book. Producers (that’s the term used by ACX; consider it synonymous with narrator for the sake of this discussion) can see the listed book and submit an audio audition for it. The rights holder listens to the auditions and can offer a contract to the producer they think will do the best job. Once the producer accepts the contract, they produce the book and submit it through ACX. The rights holder can then listen to the book, and if they approve it, it gets prepared for release. ACX manages the contract, the payment of royalties, and distribution to the associated platforms (Audible.com, Amazon.com, and iTunes.com).

‘That doesn’t sound so bad, but cut to the chase: How much will all this cost me?’

Cost is, of course, always a factor. With ACX, there are multiple options that allow virtually anyone to have their book made into an audio book. But as with many things in life, you often get what you pay for. First a quick note that there is no fee from ACX for registering on their site or for listing your book. They get their money on the back end once the book goes up for sale, so they just want to encourage as many books to be produced as possible. ACX allows rights holders to offer producers two types of contracts: Pay for Production and Royalty Share. Note that regardless of the type of contract, the rights holder always gets full ownership of the audio produced. A Pay for Production contract means that you’re paying the producer a flat fee for their work. Once you’ve paid the fee, the audio book is published and you’ll receive royalties from sales of the audio book. So what’s a typical fee? Well, first off, the fee is based on the length of the completed audio book. When you offer a contract, you agree to pay a certain amount Per Finished Hour (PFH) of the audio book. So if the audio book ends up being 10 hours long, you’ll pay the agreed-upon amount times 10. What sort of PFH rate can you expect to pay? Well, it depends on the type of talent you’re looking to attract. If you want a top-rate, full-time professional narrator, you can expect to pay around $300 PFH, or even more. ‘Wait, what!? That means for my 10-hour book …’ … you’d pay around $3,000, yes. Sounds like a lot, right? Well, it is a lot, and I touch on why that number is what it is in the full ebook. But for now, let’s get back to the discussion on cost. Because you don’t have to offer that much for a Pay for Production contract. You can offer less, and are likely to get producers willing to record your book for less. Just keep in mind that as you go lower in what you’re offering, so the caliber of producers you attract to your project will change. I’d say that once you get below $200 PFH you’re pushing out of the zone where most quality producers feel like they can get a reasonable return on their time, but that may not always be the case. A quick note: There absolutely can be an aspect of negotiation with regards to the contracts you offer. ACX doesn’t care what the final number is. That’s entirely something to be worked out between you and the producer.

‘I really don’t want to put up that kind of money. Is there another option?’

Yes, there is! It’s the Royalty Share contract that I mentioned above. In this contract, you don’t pay the producer anything up front, but instead split the royalties on sales of the book with that person. ‘Hang on – I can get my book produced as an audio book without having to actually pay anything?’ Yes, that’s pretty much it! Sounds great, right? ‘It sounds too good to be true. What’s the catch?’ The catch is that the top producers are VERY selective about the Royalty Share contracts they’re willing to accept. It takes lot of time and effort to produce an audio book, and producers who are trying to pay their bills and feed their families with money from their work won’t take a second look at your book unless it has a record of strong sales. Even if your book isn’t breaking any sales records, you can still list it and are likely to get some auditions. Just be realistic about the kind of producers who are going to be sending those auditions. They may be low on experience, talent, or both. That’s not to say it’s a hopeless case. We all have to start somewhere. Once upon a time, I was that producer who was low on experience and sending out my first auditions. The author who picked me to narrate my first audio book was an indie author who had just written his first book. While I’ve learned quite a bit since that first book, and there are definitely things I would do differently now, I’m still proud of my work on it and the critical reception has been overall quite positive. But it’ll be entirely up to you to make that determination. Just as ACX allows rights holders to sign up and post their book for free, they also allow anyone to sign up as a producer and send in an audition for free. And I do mean ANYONE. Do NOT assume that just because someone is a Producer on ACX that they actually know what they’re doing. In the full edition of the ebook, I offer guidance on how to assess whether the narrator/producer is doing a good job. For now, thanks for reading! Resources

Contact Ray Greenley Website | Facebook | Twitter

Audio-book production: A primer for indie authors from an audio-book producer

This 26-page primer (available here) includes over 5,000 words of guidance from Ray, a professional voice artist, on the following:

Louise Harnby is a fiction copyeditor and proofreader. She curates The Proofreader's Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. If you're an author, you might like to visit Louise’s Writing Library to access my latest self-publishing resources, all of which are free and available instantly.

Georgia got in touch with a training query. She’s asked to remain anonymous in order to not jeopardize her existing client relationships. I’ve therefore changed her name and removed all the details from her email that might enable colleagues or clients to identify her.

She’s based outside the UK. She has only two clients, both of which I believe are exploiting her. One pays months late on a regular basis, though it expects its freelancers to meet its tight deadlines; the other (more recent) expects her to wear far too many editorial hats given what she’s being paid for each project.

Although Georgia has several years’ copyediting experience, she has no formal training and feels that scope creep has exposed gaps in her professional knowledge. These are proving to be a challenge in her current roles. Georgia’s budget is limited (not a surprise given that she’s not being paid in a timely manner). She asks: ‘Could you suggest further steps for me? Are there any reputable online training courses you would recommend that would advance my skills and that would not be too expensive?’ So, what should she do? Training and beyond So, Georgia, first of all, I’m really impressed that you’ve focused on upskilling rather than complaining. Few editors and proofreaders know everything about everything; there’s always more to learn! Of particular interest to me, though, was the fact that you framed your query purely in terms of skills gaps and training solutions. Actually, I think there’s a bigger issue at stake: your limited choice. Your current clients expect you to be able to carry out more levels of editing than you feel capable of. And yet there are plenty of clients in the world who would benefit from – and be glad to hire you for – your existing capabilities. However, they can’t find you. With that in mind, I’m going to break down my answer into several parts:

And if that sounds like I’m looking for an excuse to bang my marketing drum yet again, I won’t apologize! The fact is that the work we do and the work we do to get the work we do are connected. Having appropriate skills is of course the foundation of good practice, but it’s next to useless if we’re still rendered vulnerable to clients who expect the earth, and believe they can ask us for it, because we have nowhere else to turn. But let’s deal with the training issue first, since that’s what you asked me to address ... Online training So the bottom line is that, as far as I’m aware, there are no ‘cheap’ distance-learning courses that will provide you with the baseline skills that mainstream publishing houses and university presses will expect from a copyeditor or proofreader. You get what you pay for when it comes to professional training. Of course, what’s cheap to you might seem pricey to me, or vice versa. Given that the pound is rather weak as I write in June 2017, perhaps some of the UK online training courses I’m about to recommend might be well within your budget today even if they wouldn’t have been three years ago! The two institutions I’ve worked with, and so can vouch for with confidence, are as follows: Bear in mind that if you decide to do proofreading training, the proof-correction markup language taught (BS 5261C: 2005) on UK distance-learning courses will differ a little from that used where you live, so there’ll be some tweaking to do when you apply the training to your practice. Below, in the comments, my colleague Corina Koch MacLeod kindly posted some additional links to online courses (see Professional Studies at Queen's University, Canada). They're open to anyone, anywhere.

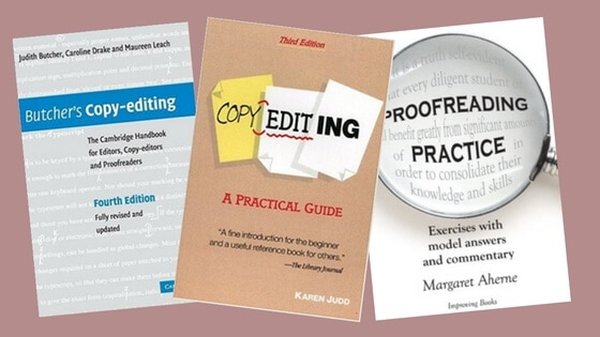

Books Online proofreading and copyediting courses are superb options because of the flexibility they offer and, in some cases, the available feedback from a tutor (that's one of the reasons why they're not the lowest-cost option). Given that you’re on a budget, though, you might want to consider books, too. Here are eight to think about:

These books most definitely aren't up-to-date in terms of technology (the on-what issue), but the best-practice elements are still spot on. The fourth edition of Butcher's is also pricey. Second-hand versions of the third edition are going for a song on Amazon, though. If you find that some of these books are out of print, ask in editorial forums if anyone has copies they’d be happy to pass on. Mentoring: formal and informal Another option is to seek either formal or informal mentoring. I don’t think you should feel embarrassed about explaining to colleagues in editorial forums that you’re looking to raise your skills to meet publishing-industry standards, and asking whether anyone would be prepared to mentor you. I'm impressed when even the most experienced editor or proofreader asks about CPD. Some may expect a fee, others will do it for free, though there might well be a wait list. Moving beyond mainstream publishers Mainstream publishers, as you know, tend to have rather rigid definitions of what a copyediting or proofreading job entails. Editorial freelancers who specialize in working for these clients do have a smoother ride if they’ve formally trained because that training accords with industry expectations. Things take a different (though not always easier!) turn when working with independent authors, students, businesses, and so on. I would not be at all surprised if the experience you’ve already acquired with your two mainstream clients means that you're more than capable of working with many non-publishers effectively. So let’s say you offer copyediting. While a publisher might expect you to edit the index or the bibliography as standard, you could decide to exclude these from your service for non-publishers. And perhaps you won’t be surprised to hear that many non-publisher clients come to me, and thousands of my colleagues, looking for so-called proofreading services. What they’re actually asking for frequently falls under the rubric of what we'd call copyediting (correcting the raw-text files) rather than annotating final page proofs. You're in a position to support this market given that you’ve already demonstrated your capabilities with several years of successful practice. See the following for more on the tangled world of non-publisher proofreading and copyediting:

A key issue for you to consider is therefore how you are going to make yourself discoverable to those types of clients. Make sure your website, social media profiles and directory entries are bang up to date and presenting you as a compelling prospect for potential clients. If you’re not advertising in the key industry directories, then that’s something you can fix immediately (whereas making your website visible is a more complex and slower-burn solution). Think internationally. If you can access key industry directories, do so. You’re not a member of the CIEP, so you wouldn’t qualify for entry in its Directory of Editorial Services, but you might be eligible for other national societies listings (see this list of national editorial societies). Then there’s findaproofreader.com, which is very reasonable. Consider other online business directories in your region, too. If their advertising rates are affordable, test them for a fixed period so you can evaluate whether they’re working for you. One channel is rarely enough for any of us. Make yourself visible on multiple platforms so you can see what drives clients your way most effectively. To make your editorial more visible to clients searching online, I’d recommended a content-marketing strategy. This requires consistency, creativity and commitment, but it is an effective strategy if you're prepared to work hard at it. I won’t use this Q&A session to delve into the issue because there’s far too much to say. If you want a taster, read my Content Marketing Primer for Editors and Proofreaders. (I also have a more general book on marketing an editorial business that might be of interest: Marketing Your Editing & Proofreading Business.) But, first, head over to the Andrew and Pete blog (two excellent content-marketing coaches, and my top recommendation for anyone wanting to dig deep and do it properly) and watch this short video: WHAT IS CONTENT MARKETING? (IN 15 GIFS). Honestly, no one makes the task as fun as these two do!

Summing up

So, Georgia, there you have it – 2 online proofreading and copyediting training options, 8 paperback alternatives, 1 brief mention of mentoring, and my thoughts on promoting yourself into a position whereby you get to define the scope of your services rather than being forced into wearing hats that aren’t made to measure! Good luck with the next steps! Louise

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Chris Hamilton-Emery, co-founder of Salt, discusses what makes a great book cover.

Managing the process of book cover design

So you’ve written, edited and prepared your book’s interior for your preferred distribution channels. Now you need the cover. And, as I know all too well, being able to write in no way qualifies one for being able to design. When we’re self-publishing, there are some parts of the process that are, for most of us, best bought in. When it comes to book jackets and digital covers, that means talking to a designer. Whether you decide to do it yourself or hire a designer will depend on your budget. Either way there are some design basics that are well worth bearing in mind to help you make your book wow itself. Great words compel your readers to finish your book ... A great cover compels them to start it. Chris Hamilton-Emery, design director of The Cover Factory and co-founder of the gorgeous independent publisher Salt (based here in mostly sunny Norfolk!) has been kind enough to share his expertise (and his fantastic sense of humour!). The advice below will help both the self-publisher and those looking for publishing contracts. Chris's core mantra? Avoid being dull.

Design by committee

For authors with a publishing contract, it’s not uncommon for a team to be involved in briefing a designer – they may not be acting as a team, but there’s often one involved. ... A sales manager who has her eye on that cover that’s on display in Book Bonanza’s shop window. ... The marketing manager who keeps up with the new trends and the language around covers: ‘It needs some spacy calmness for the furniture to show up the title text.’ ... Perhaps the bookseller: ‘Put a snake on it in a herby sort of border.’ ... The managing director: “We don’t do serifs or colour at Gubbins & Potsdamer.” ... And then there’s the production manager, the print buyer, the design manager. Everyone has something to add to the sauce, not least an expectation of stellar sales. Then someone rings the author. “He says blue reminds him of his dead mother, and the goat is the wrong breed.” Which all goes to say that cover design has its contexts. The person that truly matters is, of course, the reader – yet a cover has many important audiences before we reach that goal. That’s because it’s the chief means by which people make their investments in the book in the supply chain long before the bound paper book block (or its digital sister) touches the shelves. A cover signals commitment from the publisher (even if that publisher is you, the author); it signals desire among booksellers; it signals prospects among the supply chain, and its critics and reviewers. Many will be spending their money before anyone has read a word. For those with publishing contracts, it’s entirely possible that the author will have no contractual say in the matter, though few publishers would be brave enough to go to press with a cover that an author despised.

To boldly go?

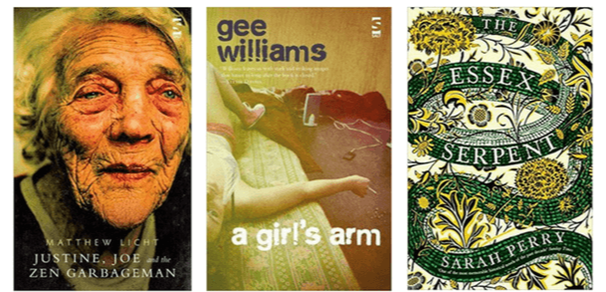

Many covers are compromises and copies, and covers, like many parts of our modern lives, are influenced by fashion. A cover that breaks ranks and stands out has as much chance of failure as success and so many covers play it safe. Being bold can also mean being ignored. As one friend put it, ‘The cutting edge is also the bleeding edge.’ Some markets have their own design universes, like crime, or romance – and it will take a brave soul to depart from the conventions of the genre. Yet we all aspire to good cover design, and we all recognize that in the fiercely competitive environment of today’s global book trade, a cover can really help make a book work, by which we mean, distinguish itself. Whomever compiles the brief has no easy task; they will be serving the multiple masters listed above and trying to find a way forward to inspire a designer to deliver a pot of gold in the shape of a small rectangle. The brief Do provide a synopsis, but not necessarily the entire book List three powerful visual moments. List one or two key visual themes. If the book had a palette, of which colours would it be comprised? How would you like readers to react to it? Do not ask for your entire book to be illustrated on the cover ‘There must be a gold sky with twenty-six ravens, and a golf house, a small bus, traffic cones and a trifle, but no jelly. And on the trestle tables, bunting. And a seal. There are two main characters, one tall, the other taller, each has a mole. They are wearing jacquard ties. They must be shown in front of the thirty-seven villagers, all attempting to get into a train. The train is going to Doncaster.’ Hmm. Detail is the great enemy of good design. Yet so, too, is needless abstraction. ‘Can it be wavy green with splashy washy bits? Except blue.’ Inspiring a great design can frequently be found in seeking out the monolithic and iconic message a successful cover often presents, ‘If she had eyes, they would be stones.’ Leave plenty of room for the designer to imagine, to take risks, and above all to surprise you with their own art. Never ask a designer to work up your own ideas. If you have ideas, especially strong ones, express them as visual journeys. Don’t offer destinations. Ask questions Perhaps the best way to ask questions is to show things that you believe work for you – other covers that appeal, especially ones relevant to the text. Create a visual space for the designer to work in, and add your brief to provide context and challenges. Good questions expose the problem, good questions get to the central, even the reductive, theme of the book. ‘If there was ever a home like this, it would be a songless house on a wet hill with a red rat at its heart.’ So, again, ask for three visuals, perhaps some early sketches, to see where things are leading. Or be bold and say, I am prepared to be surprised.

Consider the compulsion factor

It’s also important to know the mechanics of a cover – once it’s passed through its committees and is en route to the bookstore, its role really comes into its own. Among the tens of thousands of books being put in front of readers, in stores or online, the cover’s job is simply to attract the browser, that momentous millisecond of compulsion that makes someone pick the book up, read the blurb and break open the spine. Or scroll down a page and click Look Inside. Think of it. You spot something, your eye stops its movement, you lean forward and pick up the book, you turn it over and read an endorsement, your eye flickers, you read down. Ah, it’s about the last water mill in a land of drought ... You open the book and a journey begins (one that starts at the till). Think back. The cover merely had to stop you moving on and its work was almost done – such a simple and perplexing thing. Would something more complicated have worked better? Something less fussy? Something less drab? The essentials ... Not everyone can afford a £3,000 cover budget; nor are they willing to have a six-month internal circulation list for everyone to argue over within a publishing house. You may be going it alone; you may be self-publishing. The problems are still the same – your cover must be distinctive, distinguishable, memorable, singular and arresting.

Free fonts can help in devising sketches. Test your ideas out with professionals. Don’t test them out with friends. Look at your cover in the context of your competitors. And give it time. If you’ve spent years writing your book, at least give a few months to considering the cover. Be aware of your own prejudices. Be aware of your own tastes. Pay attention to space and position, to colour and clarity. And if your book is to be printed, above all, remember the spine, for this is what most readers will see. Don’t mistake a poverty of design as the representation of authenticity. Don’t over elaborate, either. Look at your cover from twelve feet away; can you recognize it, read it?

Working with the designer ...

Let’s roll back through these notes towards a design. If we’re using a designer, we want to enthuse and inspire, we want to ignite not instruct. We want to understand the context in relation to other covers. We want to be aware of those who will put our book in front of readers. We want the readers to pick it up or click on it. Whether we use a designer or produce something ourselves, we are all chasing something singular, clear and memorable. We are avoiding complexity. We are signifying the book more than illustrating its contents. Above all we are branding it. Remember that brands symbolise and represent complicated relationships and stories by simple means. Simple doesn’t mean dull. In fact, perhaps the best mantra is, don't be dull. The world needs its little moments of glamour.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Here's why new freelance editors and proofreaders need to commit to marketing, rather than relying on word of mouth to grow their businesses.

In 'When one client isn’t enough – emergency marketing for editors and proofreaders', I offered an emergency marketing plan for proofreaders and editors who’d either lost their sole source of income or ended up in a situation where they were reliant on one client.

The first stage of the marketing plan asked for a commitment to active marketing. If you’re simply waiting for a solution to present itself, you’re merely involved. And that’s a very different proposition from being committed. I love this quotation from Martina Navratilova: The difference between involvement and commitment is like ham and eggs. The chicken is involved; the pig is committed.

Editorial freelancers, especially new starters, need to be the ham. Committing to marketing as soon as we set up our businesses ensures that we’ll never be client-reliant or, worse, lose our sole source of income.

Acquiring work: commitment versus involvement Involved: being passive Most experienced editorial freelancers take advantage of passively acquired work. I have a number of repeat clients who fill some of my schedule. If you’re highly visible, experienced, trusted and respected, this strategy could well be effective for you. For the new entrant to the field, though, it’s a non-starter. That’s because these opportunities are a consequence of active marketing. Passively acquired work might come through a variety of channels. Here, for simplicity, I’ve focused on three:

Committed: being active Active marketing is the work you do to generate these passive opportunities. Here, again, I’ve focused on three: A. Networking with colleagues and clients (e.g. on editing forums, at conferences, professional society meetings, social media platforms). This kind of marketing leads to an awareness of what your specialist skills are. If a colleague needs to direct a client or prospect to someone with skills or availability that he or she doesn’t have, you’ll be in the running (see 1, above). B. Cold-calling and writing letters/emails to target clients (e.g. publishers, packagers, businesses, marketing agencies). This is direct marketing and if you do it extensively you can quickly build a solid list of similar client types. If the clients are satisfied with the work, they’ll rehire you, which leads to repeat work (see 2, above). C. Just creating online profiles in itself is not enough to make you discoverable. Action that maximizes the visibility of those profiles in the search engines is key. This is where content marketing comes to the fore – creating and distributing (via your online platforms) advice, knowledge, tools and resources that your colleagues and clients will find useful, valuable. Examples include blogs, booklets, video tutorials, checklists and cheat sheets. High-quality content offers solutions to problems and makes your online profiles more findable (see 3, above). In a nutshell, being active enables you to reap passive rewards later (if your office buddy will give you the space, that is).

Why word of mouth (WOM) is often misunderstood

‘But my colleague said that all her work is via word of mouth.’ I don’t doubt it. But if she’s been running her business for 20 years and has a portfolio and client list as long as your arm, she’s not in the same position as the new entrant to the field. She’s benefiting from 1, 2 and 3 because she invested in A, B and C. New starters should indeed commit to WOM marketing. What they shouldn’t do is assume that it’s a passive approach that requires no effort. Nor will there be short-term results. Top-notch WOM marketing requires an intense level of commitment to action and an acceptance of slow-burn impact. Awareness and trust aren’t built overnight, especially in our field. Editorial freelancers aren’t selling a product that promises something that swathes of people have wanted forever – an anti-aging cream, a painless leg-waxing treatment, a broadband connection that never, ever buffers even if you live out in the sticks and there’s more chance of getting a wi-fi signal on Mars. Our services have to prove their worth. For the editorial business owner, WOM marketing is like creating a garden from scratch. If you’re proactive, it will take many months to knock it into shape. If you hold back, it’ll take years. If you’re passive, the garden will remain barren. WOM and colleagues There are a lot of us, and many have already developed niche networks of friends and colleagues to whom we refer work. When an editor or proofreader ends up on my radar, it’s because they’ve instilled trust in me.

WOM and clients As for client A telling client B about you, you’ll need a lot of mouths to share the good news if you want to have a full schedule! That’s not where you’ll be if you’re a new entrant to the field, not because you’re not an effective editor or proofreader but because you don’t yet have a large enough bank of clients. Effective WOM Find out which networks (online and offline) your clients and colleagues recommend and join in the discussion. There’s nothing wrong with asking questions but be prepared to offer solutions too. Even new editorial freelancers have specialist skills and background experience that are relevant and valuable to the debate. In 'Why word of mouth marketing is the most important social media', Kimberly A. Whitler, Assistant Professor at the University of Virginia's Darden School of Business, breaks down WOM marketing into the three Es:

Action first, passivity later Clients can come via active and passive marketing strategies. It’s not a case of the right strategy but the right order. If you’re a new starter, make active editorial business promotion a standard part of your working life, just like copyediting or proofreading, invoicing and updating your software. Assign space for it every week so that it becomes commonplace rather than a chore or, worse, something to be feared. Be active. Be committed. Be the ham! Once your business is established, you’ll be able to take advantage of the passive benefits that result from your effort. Just take care not to hand over the chill space to your Labrador!

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses. In my latest guest article for the BookMachine blog, I take a look at how publishing professionals, from the freelance editor to the mainstream publishing house, can stretch their marketing budgets by repurposing one in-depth piece of amazing content. The fabulous Gordon Graham, otherwise known as That White Paper Guy, was my inspiration, and I'd recommend you take a look at his guidance on ways to create brilliant resources to make your clients' lives easier. Click on the stretchy guy to read the article in full! Louise Harnby is a professional proofreader and copyeditor. She curates The Proofreader's Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. |

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed