|

Chris Hamilton-Emery, co-founder of Salt, discusses what makes a great book cover.

Managing the process of book cover design

So you’ve written, edited and prepared your book’s interior for your preferred distribution channels. Now you need the cover. And, as I know all too well, being able to write in no way qualifies one for being able to design. When we’re self-publishing, there are some parts of the process that are, for most of us, best bought in. When it comes to book jackets and digital covers, that means talking to a designer. Whether you decide to do it yourself or hire a designer will depend on your budget. Either way there are some design basics that are well worth bearing in mind to help you make your book wow itself. Great words compel your readers to finish your book ... A great cover compels them to start it. Chris Hamilton-Emery, design director of The Cover Factory and co-founder of the gorgeous independent publisher Salt (based here in mostly sunny Norfolk!) has been kind enough to share his expertise (and his fantastic sense of humour!). The advice below will help both the self-publisher and those looking for publishing contracts. Chris's core mantra? Avoid being dull.

Design by committee

For authors with a publishing contract, it’s not uncommon for a team to be involved in briefing a designer – they may not be acting as a team, but there’s often one involved. ... A sales manager who has her eye on that cover that’s on display in Book Bonanza’s shop window. ... The marketing manager who keeps up with the new trends and the language around covers: ‘It needs some spacy calmness for the furniture to show up the title text.’ ... Perhaps the bookseller: ‘Put a snake on it in a herby sort of border.’ ... The managing director: “We don’t do serifs or colour at Gubbins & Potsdamer.” ... And then there’s the production manager, the print buyer, the design manager. Everyone has something to add to the sauce, not least an expectation of stellar sales. Then someone rings the author. “He says blue reminds him of his dead mother, and the goat is the wrong breed.” Which all goes to say that cover design has its contexts. The person that truly matters is, of course, the reader – yet a cover has many important audiences before we reach that goal. That’s because it’s the chief means by which people make their investments in the book in the supply chain long before the bound paper book block (or its digital sister) touches the shelves. A cover signals commitment from the publisher (even if that publisher is you, the author); it signals desire among booksellers; it signals prospects among the supply chain, and its critics and reviewers. Many will be spending their money before anyone has read a word. For those with publishing contracts, it’s entirely possible that the author will have no contractual say in the matter, though few publishers would be brave enough to go to press with a cover that an author despised.

To boldly go?

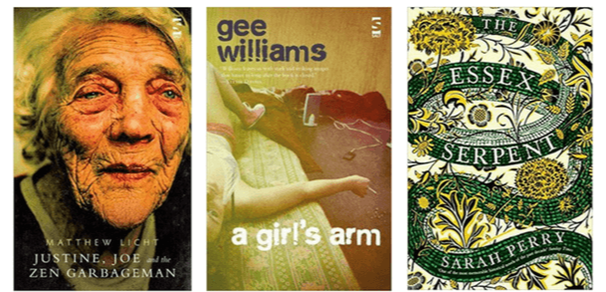

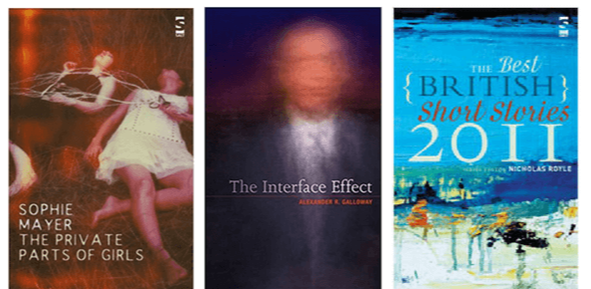

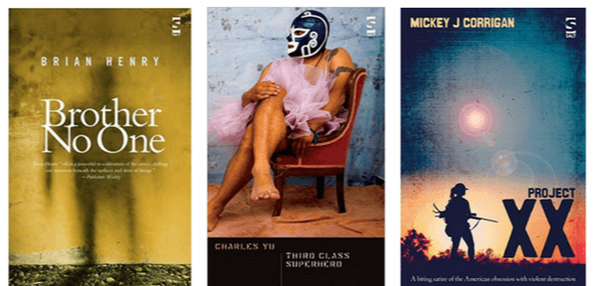

Many covers are compromises and copies, and covers, like many parts of our modern lives, are influenced by fashion. A cover that breaks ranks and stands out has as much chance of failure as success and so many covers play it safe. Being bold can also mean being ignored. As one friend put it, ‘The cutting edge is also the bleeding edge.’ Some markets have their own design universes, like crime, or romance – and it will take a brave soul to depart from the conventions of the genre. Yet we all aspire to good cover design, and we all recognize that in the fiercely competitive environment of today’s global book trade, a cover can really help make a book work, by which we mean, distinguish itself. Whomever compiles the brief has no easy task; they will be serving the multiple masters listed above and trying to find a way forward to inspire a designer to deliver a pot of gold in the shape of a small rectangle. The brief Do provide a synopsis, but not necessarily the entire book List three powerful visual moments. List one or two key visual themes. If the book had a palette, of which colours would it be comprised? How would you like readers to react to it? Do not ask for your entire book to be illustrated on the cover ‘There must be a gold sky with twenty-six ravens, and a golf house, a small bus, traffic cones and a trifle, but no jelly. And on the trestle tables, bunting. And a seal. There are two main characters, one tall, the other taller, each has a mole. They are wearing jacquard ties. They must be shown in front of the thirty-seven villagers, all attempting to get into a train. The train is going to Doncaster.’ Hmm. Detail is the great enemy of good design. Yet so, too, is needless abstraction. ‘Can it be wavy green with splashy washy bits? Except blue.’ Inspiring a great design can frequently be found in seeking out the monolithic and iconic message a successful cover often presents, ‘If she had eyes, they would be stones.’ Leave plenty of room for the designer to imagine, to take risks, and above all to surprise you with their own art. Never ask a designer to work up your own ideas. If you have ideas, especially strong ones, express them as visual journeys. Don’t offer destinations. Ask questions Perhaps the best way to ask questions is to show things that you believe work for you – other covers that appeal, especially ones relevant to the text. Create a visual space for the designer to work in, and add your brief to provide context and challenges. Good questions expose the problem, good questions get to the central, even the reductive, theme of the book. ‘If there was ever a home like this, it would be a songless house on a wet hill with a red rat at its heart.’ So, again, ask for three visuals, perhaps some early sketches, to see where things are leading. Or be bold and say, I am prepared to be surprised.

Consider the compulsion factor

It’s also important to know the mechanics of a cover – once it’s passed through its committees and is en route to the bookstore, its role really comes into its own. Among the tens of thousands of books being put in front of readers, in stores or online, the cover’s job is simply to attract the browser, that momentous millisecond of compulsion that makes someone pick the book up, read the blurb and break open the spine. Or scroll down a page and click Look Inside. Think of it. You spot something, your eye stops its movement, you lean forward and pick up the book, you turn it over and read an endorsement, your eye flickers, you read down. Ah, it’s about the last water mill in a land of drought ... You open the book and a journey begins (one that starts at the till). Think back. The cover merely had to stop you moving on and its work was almost done – such a simple and perplexing thing. Would something more complicated have worked better? Something less fussy? Something less drab? The essentials ... Not everyone can afford a £3,000 cover budget; nor are they willing to have a six-month internal circulation list for everyone to argue over within a publishing house. You may be going it alone; you may be self-publishing. The problems are still the same – your cover must be distinctive, distinguishable, memorable, singular and arresting.

Free fonts can help in devising sketches. Test your ideas out with professionals. Don’t test them out with friends. Look at your cover in the context of your competitors. And give it time. If you’ve spent years writing your book, at least give a few months to considering the cover. Be aware of your own prejudices. Be aware of your own tastes. Pay attention to space and position, to colour and clarity. And if your book is to be printed, above all, remember the spine, for this is what most readers will see. Don’t mistake a poverty of design as the representation of authenticity. Don’t over elaborate, either. Look at your cover from twelve feet away; can you recognize it, read it?

Working with the designer ...

Let’s roll back through these notes towards a design. If we’re using a designer, we want to enthuse and inspire, we want to ignite not instruct. We want to understand the context in relation to other covers. We want to be aware of those who will put our book in front of readers. We want the readers to pick it up or click on it. Whether we use a designer or produce something ourselves, we are all chasing something singular, clear and memorable. We are avoiding complexity. We are signifying the book more than illustrating its contents. Above all we are branding it. Remember that brands symbolise and represent complicated relationships and stories by simple means. Simple doesn’t mean dull. In fact, perhaps the best mantra is, don't be dull. The world needs its little moments of glamour.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed