|

Knowing when to intervene and when to leave well enough alone is something most of us struggle with at the start of our editing and proofreading careers. This reader question highlights another dimension, that of concern with damaging authorial style in fiction. Here's my take ...

John says:

I am struggling with repetition versus an author’s style. Is there a section in New Hart’s Rules about this? Is there a golden rule that should always be followed? Is it necessary to point out repetitions if there are only two or three in a text of four pages, or if they’re in different paragraphs or in the same sentence? Thanks for your question, John. Broadly speaking, I think that as soon as something has a negative impact on the reader’s ability to navigate the story, we’re into the territory of finding solutions rather than respecting style. But more on that below. First, a caveat … The difference between voice and style You didn't ask about this, but it's something that beginner fiction writers and editors often struggle with so I decided to provide an overview here. Voice and style are often presented as the same thing in discussions about writing and editing. Actually, it's more complicated because there might be multiple voices in a novel, but one authorial style. Consider the example of a crime novel: Thinking about voice(s) In this example, the story is told through multiple points of view, though only one POV is presented per chapter – so we might follow the action through the eyes of Simon Smith in Chapter 1, and Nicole Jenson in Chapter 2, then back to Simon in Chapter 3. The narrative is written in the third person, so the voice is that of the narrator, though we will also hear Simon's and Nicole's voices through their dialogue. Still, the narrative voice should be consistent in both chapters. Overall, though, there are multiple voices in the novel – the characters’ and the narrator’s. Thinking about style Let's imagine that the author prefers short, choppy sentences to convey drama, tension and fear. Omits pronouns to keep things lean. Sometimes. He often uses contractions (I’m, we’d, you’re) to aid flow and mimic informal, natural speech patterns. And to convey emotion, he leans on dialogue rather than detailed description. All of this is his authorial style. It's present throughout the 10-book series and pulls it together. Readers can identify the books as having been written by the author in part because of the consistency of style. Now that we've made a note of that, let's return to the problem in hand ... Style versus poor writing The fiction editor needs to be aware of the difference between a style choice and a readability problem. Consider the following: 1A: She always named her cats after favourite aunts; this one was called Molly. 1B: She always named her cats after favourite aunts. This one was called Molly. 2A: He looked over his shoulder and almost felt the arrow as it whistled past. 2B: He looked over his shoulder. Almost felt the arrow as it whistled past. 3A: They walked to the end of the long hallway. At the end of the hall there was an open door beyond which lay three more hallways. They chose the left one and continued towards the interrogation room, no one said a thing as they walked. 3B: They walked the length of the hallway in silence. They reached an open door, and took a left towards the interrogation room. In 1A there’s a style choice regarding semi-colon use, and I’d respect this unless the author had specifically asked me to omit semi-colons (in which case I’d amend to 1B). In 2A there’s a style choice regarding sentence length. I’d use my judgement here. I might suggest 2B, explaining in a comment that I felt it conveyed a sense of tension more in keeping with the scene and the author’s usual style. Or I might offer two options: 2B and an alternative: He looked over his shoulder, almost felt the arrow as it whistled past. In 3A, there are multiple problems – chiefly repetition, poor flow and a comma-splice. I don’t want to rewrite the book for the author – that’s not my job – but I can’t leave this as it is. I need a sensitive recast but I need to work with what I have. I might suggest something on the lines of 3B. And that’s the difference. In 1A and 2A the readability isn’t impaired. In 3A it is. If an author’s style is to write poorly, the editor must intervene. Readability trumps poor style. Our job when line editing and copyediting is to smooth and correct when things are rough and wrong. To leave as is because ‘it’s the author’s style’ cannot be justified. To do so would render the role of the editor obsolete. We’re hired to sort out problems, and attend to them we must. Golden rules, or lack of them When it comes to line editing fiction, there’s no rule book (New Hart’s or otherwise) that will tell you what you must fix and how you must fix it. Each project's different, each brief’s different, and the style and voice(s) in the text will be different. Above all, it’s intuitive. It takes into account the tension, pace and mood of a scene, and whether the repetition is obvious and makes the writing look amateurish, or whether it’s necessary and key to the novel’s trajectory. You need to feel your way into the story, get under the skin of the writing, and make sure the reader can move forward without stumbling. And how you, John, approach it might not be how I approach it because we're two different people and our impressions are subjective. Furthermore, whether and how you deal with repetition problems will depend on frequency, proximity, what you’ve agreed with the author, and whether the amendments are essential, preferred, or, rather, gentle improvements. Different line editors would handle 3A in different ways. Some would flag the problem; some would flag and explain it; yet others would flag, explain and suggest a solution. My preference is for the latter (unless I'm proofreading). Assuming we need a recast to avoid repetition in 3A, we could do one of the following:

The approach you choose should be based on what you’ve agreed with the author beforehand. I work with some authors whose novels require heavy line editing. To keep costs down, we agree that I’ll amend the text directly rather than commenting excessively. In such cases, the authors have decided they trust me to intervene in a way that’s sensitive to their style and the voice(s) in the book. I have other clients who prefer deeper recasts to be offered in the comments. If you’re not sure how to solve a problem, or you think there are multiple solutions to dealing with repetition, the query trumps the amendment every time. I do have some 'rules'! These are not about the what but the how. Perhaps they’ll help you communicate with your author about the repetition problems in a productive way. The mindful rules of fiction editing

What’s the brief? One thing you didn’t’ mention in your query was what level of editing you’d been commissioned for. It takes time to sort out sentence-level problems such as 3A. Correcting the comma splice is a quick fix and takes a second. Creating a recast that’s emotionally responsive to the author’s style and the voice(s) in the narrative and dialogue is a different kettle of fish. Correcting the comma splice falls within my definition of proofreading – the final quality-control or verification process. The recast absolutely does not; it’s deeper sentence-level editing and has to be priced as such because it takes longer to fix. Frequent repetition problems are usually evident in a sample chapter, so the editor should be able to see whether the level of edit requested is appropriate. If you’ve been commissioned to proofread and you find yourself dealing with a few issues of repetition here and there, it’s unlikely to impact on your hourly rate; just make a gentle note in your handover report. If the file is littered with repetition that renders the work unpublishable, and this wasn’t evident in the sample you were sent, you’ll need an emergency discussion with your author to explain the problem and come to an agreement as to how to proceed. Summing up I hope this has helped. The key is first to focus on the reader’s experience. That will be your best guide as to whether the repetition needs attending to. Then focus on your relationship with the author and let that guide you as to how best to communicate the problem via direct amendment, commenting or a mixture of the two. And don’t forget the mindful rules! Further reading

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with independent authors of commercial fiction, particularly crime, thriller and mystery writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Society for Editors and Proofreaders (SfEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

0 Comments

What's different about fiction editing, and is it for you? This post explores emotional responsiveness, mindfulness and artistry.

To keep things tidy, I'm talking in the main about line editing and copyediting because I specialize in sentence-level work, but some of the key principles will apply to developmental fiction editing too.

Why fiction editing is a different kind of artistry Have you ever tried something for the first time and found it difficult? Did someone review your initial effort? Did they outline problems before celebrating your achievement? If so, how did you feel? I suspect most of us have encountered this scenario at some time or other. I have, and it feels just awful. A review of anything that focuses only on the negatives – however kindly those negatives are offered – is a poor review. It matters not whether you’re an editor, a business executive, a marketer, or a parent; if you can’t find a single good thing to celebrate in the work in front of your nose, then you’ve not done the job properly. When editing fiction, the ability to celebrate first is critical – more so, I think, than with non-fiction. Note that by non-fiction I’m referring to academic, technical and journalistic works, not narrative non-fiction (sometimes called creative or literary non-fiction) such as memoir or biography, where I think the editing challenges are similar to the fiction specialist’s. In a nutshell, editing criminology requires a different touch to editing crime fiction.

It’s personal

Every writer’s book is their baby, and most writers will infuse their tomes with their own experiences. But when those experiences concern matters of love, grief, sex or despair, the process of writing – and of being edited – takes on a whole new level of intimacy. I’ve lost count of the number of authors who’ve told me they felt physically sick at the thought of contacting an editor, never mind emailing me the file. Many feel vulnerable, exposed, embarrassed. And why wouldn’t they? Imagine handing over hundreds, even thousands of pounds to a stranger to look at an image of you and suggest how to make it better – not just any image, mind. You’re naked in this one. For many, that’s what it feels like to be edited. And so the fiction editor is charged with a responsibility. And it’s huge.

Best versus best fit

Put 10 fiction editors in a room and ask them to work on the same 2,000 words. You’ll likely come back with 10 very different samples. That’s because fiction editing is subjective. It’s not that the rules of grammar, spelling and punctuation don’t apply. It’s not even that they apply less rigidly. It’s rather that they apply differently. Just a single change to a punctuation mark can affect tension, pace, mood. One of my regular authors has a mantra: ‘Louise, as always, keep it lean and mean.’ He’s a crime writer. It’s high-octane stuff. Low on adverbs. Low on conjunctions. Short, choppy sentences. The protagonist looks over his shoulder a lot. And if the punctuation is sympathetic, the reader looks with him. Compare this with another recent project. It’s essentially a love story – a woman’s search for her exiled family. The tale is one of heartbreak, abandonment, reconciliation and redemption. The author’s style is more fluid, prosaic. The protagonist isn’t looking over her shoulder but searching her soul. Every change needs to reflect this. How I go about reflecting these authors’ intentions will not necessarily be the same as one of my colleagues. It’s not that one of us is better at editing than the other. Rather, it’s how we interpret those intentions – and seek to mimic them – that’s different. We’re not talking about who’s the best, but who’s the best fit. That’s something the author must decide. And it’s tricky. How does a writer search for best fit on Google, or in an editorial directory, or on social media? How do they find that elusive emotional responsiveness to their writing?

Gauging emotional responsiveness – the sample edit

Fiction editors don’t have a monopoly on sample edits, but there is, I believe, an added dimension here in which samples really come into their own. Physically working on a piece of text helps every editor get a sense of the writing style, where the problems are and whether they’re capable of solving them, how long the job will take and how it should be priced. For the fiction editor, there’s something else, though – the feel of it. It’s our first opportunity to find out whether we can get under the skin of the author. And if we can’t, it might mean walking away. If we can’t respond emotionally to the author’s intentions – feel our way through the words and into the characters and the world they inhabit – the edit could be impaired. You can’t mimic an author seamlessly if you’re unmoved by what you’re reading. There’s a lot of talk about authorial voice in the editing world. In fiction editing, the concept can be a tad limiting.

A sample edit has its limitations, of course, by virtue of size. But it gives the author and the editor a glimpse of whether that emotional responsiveness is present and how it’ll be managed on the page such that the fit feels right. Ultimately, fiction editing is as much about the heart as the head.

The mindful rules of fiction editing

Once the author and editor have found each other, the mindful rules of fiction editing will come into play ... during the edit, and in the post-edit summary or report. Here are mine:

Fiction is a specialism

Fiction editing isn’t for everyone. If you’re keen to specialize in this kind of work, ask yourself where you lie on the empathy scale. Many specialist fiction editors I know describe themselves as being a little on the oversensitive side. Terms such as introspective or contemplative are never far away. I cry at some adverts, so it’s no surprise to me that I ended up in this line of work! This emotionality can serve the fiction editor well, but it’s not something that can be learned on a training course. That’s not to say that specialist fiction editorial training isn’t worth doing – far from it. But mindfulness is your friend, too – don’t be afraid to embrace it in your editorial practice!

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Ever wondered how a professional book index is created? My colleague Vanessa Wells offers an honest and humorous glimpse into the world of a pro indexer – the challenges and the joys, and the 'sense of having created a beautiful thing'.

Let's take a peek in Vanessa's diary ...

I attended the Canadian national indexing conference in Montreal, where we – like most conference attendees – go to strengthen connections with colleagues and expand our professional knowledge. Since the indexing community in Canada is very small, this is a valuable investment and full of good people.

As a result of the conference, I’ve received a referral and am being hired by a university professor to write an index for a 220K-word anthology he’s editing with 22 chapters and almost as many contributors. It’s a ‘straightforward’ index of ‘names and titles’ which, of course, means that it’s both a name and subject index in reality. Yikes.

Against my usual policy, I agree to meet the professor in person, as the campus is close by and it would be faster than exchanging several emails. An excellent meeting results in ironing out expectations, discussing needs and agreeing we’re on the same page! It’s due July 26.

I send him my contract to review, and we discuss rates. Rate structure, I find from speaking to other indexers, is variable. Some people will work for $2/page; others charge much more. A figure I often hear is $5/page, but that definitely depends on your market – geographically and by genre, specialization, and timeline. An independent author writing a non-fiction trade book is not going to generate the same fee as a university-paid gig. Some indexers provide other means of calculating their fees, such as a flat project fee. I tell him my academic rate, and he agrees. I submit my invoice for a non-refundable 30% deposit, payable before work begins.

Proofs are due. They don’t arrive. They’re rescheduled by publisher for the 30th … While publishing timelines are often shifting (there’s a domino effect when a hitch arises), the end deadlines of proofreading and indexing are rarely budged.

So now I have to recalculate the number of hours and pages per day I’ll have to complete to meet the non-budging due date of July 26. Four days lost means Goodbye, weekends! for the duration.

It’s a long weekend here for #Canada150, our sesquicentenary. I’m so wiped from the previous month of conferences and making a second website for the new arm of my business that I take (most of) the weekend off. I can’t afford to get sick during this project. Self-care and all that.

Forgot I start a weekly course on Tuesday afternoons for the summer, with an appointment this morning. Will have to start tomorrow. Now that I’ve lost another 5 days, I’ll have not only to work weekends but very long days, everyday. My bad.

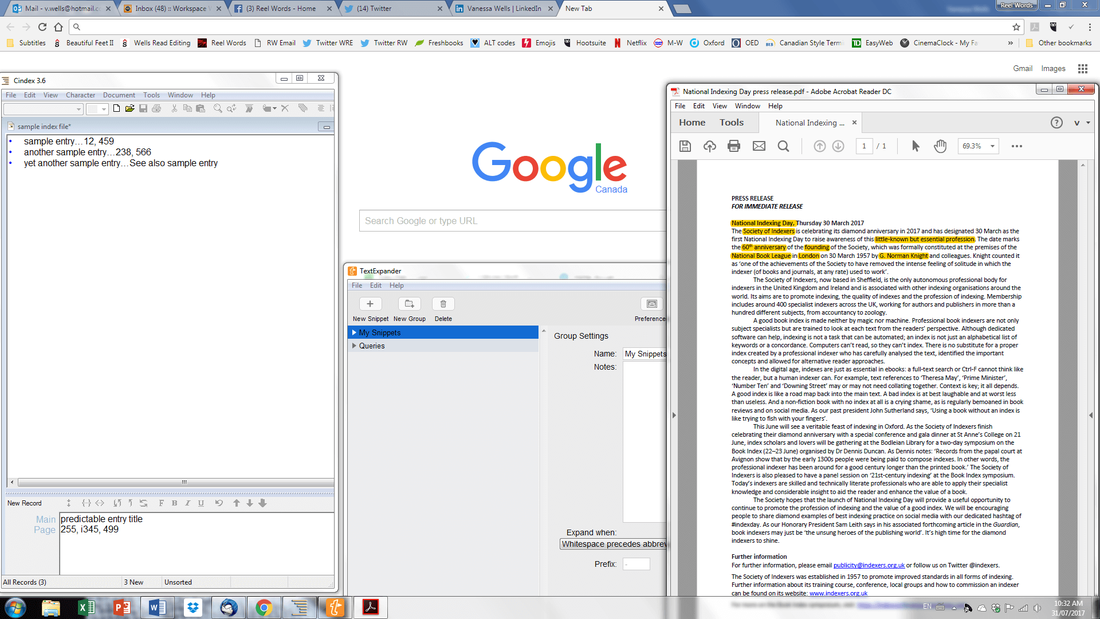

21 days to go: I begin the pre-read (see above photo) to start gathering my thoughts on how I’ll approach this behemoth. And I need at least 3 days at the end to edit the written index, so really I only have 18 days available.

I note there are A LOT of errors still in the MS. I judiciously email AU to double check that it’s been edited and that no other file is forthcoming. He confirms it has been copyedited … Sigh.

Re-install my $500USD indexing software on my new PC. Pay $39 for TextExpander, which is an online tool that lets you build a library of ‘snippets’, sort of like hot keys or macros, but it’s much simpler and faster. Using TextExpander for repeated, long index headings is making my life so much easier: it works pretty well with .ucdx files!

I’m already 50 pages behind. Indexing academic books is so much harder because you have to interpret the often-verbose language to get to the ideas (then re-edit them in your mind) and THEN start forming index relationships between the ideas on that and every other page.

Since there are almost two dozen authors in this anthology, I’m doing a lot of mental shifts. Why do I pine for indexes so much when they can be so draining?!? I’m being foiled by the very poor copyediting that was(n’t) done. I email the author-editor several times regarding his preferences for word options that I’m finding in the errata …

Working on a Saturday is particularly annoying when you hear other people having a great day off. Such is the freelance life.

Here’s how I start an indexing day. Wish I had more than one monitor and can’t believe I used to do this on a 15-inch one!

CINDEX software file open; Google to check MS info, with related sites and academic books on the subject; book PDF marked up with terms needing indexing; and TextExpander to cut down on keyboard strokes. For the time being, I just type the entries into the index; refining connections comes later.

I emailed the author again about the serious issues around the practically non-existent copyediting of this book. It’s causing me to complete about 3pg/hr instead of 5–10pg/hr, never mind that I’m not being paid to correct such things, so again my budgeted time has to be rethought. He’d like errata forwarded to him so he can take the examples to the publisher and complain. (Understandably, he just doesn’t realize how much is involved in corrections before indexing can be done: research, confirm which instance is the error, note error, find other instances of it in MS, return to indexing the term and fixing all related cross-references). Ctl+F is my BFF. Wish I still drank alcohol. And for all you fellow CCLs, here’s what’s behind it all (because this, after all, is what’s important in life, not crying over indexes).

I had a good phone chat with the author about the terrible editing. (Again breaking the rules; normally I never share my number – learned the hard way with an abusive client once – but there’s too much to discuss via email.)

We’re hatching a plan to shame the publisher into redoing the copyediting or letting me do it. Either way, my schedule is messed up, and he’s sympathetic. What he’s told me about their process with him this far is appalling.

Email from author: basically, the publisher will redo the copyediting after indexing (!!!). This is a problem because it can affect pagination, thus rendering entries incorrect. I asked that my name not be included due to peer reviews in a trade journal, and I wouldn’t want residual index errors to be ascribed to me. The prof was cool with this; I am not, but that’s life in publishing.

Slogging away, only getting about 35 pages/day done. Have to step it up to get in an extra day for editing the index. I hired a subcontractor to proofread it the day before it’s due. I need an emoji for dollar bills flying away. [Note from Louise: I've obliged.]

Tenth day. Just shoot me.

I’ve put in 12 hours today. I’m starting to wonder if I’m going too deep with this index. Re-evaluating.

Good thing I hate summer weather. I worked smarter today, however, using more automations.

Panic time. I’m only at pg 385 out of 557 and I have less than 4 indexing days left before I start editing.

Trying a new – and, to me, risky – tactic: indexing on the fly, not marking up first. I’ll see how one chapter goes. I’ve got to save time! I’ve subcontracted out a small job (1–2 hrs) due to the copyedit snafu. I need every hour I can get. I figure it’ll be worth the money.

What happened to yesterday? Feel like I’m getting sick, which would be disastrous. As an editor, I can always subcontract out a project for an emergency, but not only does indexing have a smaller pool of trained professionals, the intricacies of indexing style are so individual that really no one could easily or seamlessly take over. At least, not if the index is to retain its integrity and essence. Sigh.

Yay, I’m not sick! Done the inputting of entries! 6,388 records, which is on par for a book of this size and topic. The hard part is yet to come: finessing the cross-references and making links to interrelated concepts. While the software can help check for bad references and missing locators, there are many variables to consider. Some cross-references will have to be truncated and reworked; others will simply have to go; and yet others will require double posting due to wording.

This is the part that indexers must educate authors and publishers about – explaining that Word’s ‘indexing’ program just cannot replace a trained human brain. Word creates a concordance: that’s like taking the ingredients off a cereal box and listing them in alphabetical order. An index, analogously, takes the main words, interrelates them, looks at their nutrient values and considers how the ingredients work to give us a food product, but we can also just know what’s in there if that’s all we need. In fact, there’s our professional comparison: indexers are the food chemists of the book world – ta da! This stage is exciting and a bit terrifying. I read an article in our UK journal, The Indexer, wherein another indexer (Margie Towery, Ten Characteristics of Quality Indexes) admitted to having two moments of feeling stuck during the process: getting started and this stage. Glad I’m not the only one!

I’m just doing some basic cleanup so that I can get to the editing described yesterday. Fixing typos deletes erroneously duplicated entries and ensures consistency: now’s the time to go back to the MS and confirm correct spellings; get rid of unnecessary, duplicated or differently phrased duplicate subheadings (the latter because you don’t see repeats in the Draft Format that you might have entered previously); add subheadings for entries that have too many unrelated locators, etc.

It’s 11 a.m. and I’m only at the Cs. As the meteorologist at the beginning of Twister says, ‘This is going to be a long day’…

Finished cleanup from the Ms to Z; also a lot of double-checking that sufficient entries existed for major and meta topics, as well as the book’s contributors, which the author-editor requested. I’ve planned out the editing for tomorrow before a review by software on Monday.

And to prevent potential meltdowns, I save every 30 minutes or so, and back up to hard drive and Dropbox every 4 hours. That’s because once someone turned off the fuse box, and I lost a huge part of an index I had been working on. Live and learn.

Sunday morning, so starting late at 10 a.m. I had a good night’s sleep, which is great because today’s to-do list is intimidating … Except my optical mouse isn’t working, so thank god I have a wired spare. Kind of like giving a chef a loaner knife they’re not used to.

The mouse worked after a reboot, but the reboot took about 20 mins, so essentially I’m half an hour behind again. I can’t just Control + F terms in the PDF, type the page numbers in and I’m done: half of them are in citations, references or footnotes, and the latter should usually only be included when they’re substantive (which can take some time to decide). So whittling down the number is time-consuming. Then they have to be organized by thought. Then entered, and without page-number errors.

Butterflies. I heard a reminder on the radio yesterday talking about how, philosophically, Good Enough should be good enough, i.e. that striving for perfection is not good for us. I don’t think this is the inclination of the indexer (or editor or proofreader for that matter), no matter who says it. But I’m sure Annie Lamott would tell us to be gentler with our sorry-ass selves.

I confirmed that the proofreader is available to complete their part tomorrow. On to my penultimate review …

Due to other commitments, I had to forget about the index today and trust it would be well proofread by my subcontractor. Not easy to do ...

Bad dreams all night about repeatedly calling said subcontractor because the file was late.

Spent several hours correcting, finessing, re-sorting (getting the locator order right – Roman numerals, ascending page numbers interspersed with those with an i for illustration (sometimes we just put illustrated page numbers in italics), so it would show thus: ix–x, 132, i234, 496), and double-checking things before putting it in a double-columned .rtf file. I’ve heard that before this editing stage, an error rate for page numbers of about 10% can occur, but with the ones my subcontractor found, I was at 0.002% errors: I hope that’s true! Corrected, I hope it’s near-perfect. Even human indexers with software can make mistakes. In a book of 220K words to be considered for indexing, perfection cannot be expected. I’ve clicked Send …

Anti-climax: the author couldn’t access the file properly (the .rtf was showing up strangely), so he just asked for a new file format. He hadn’t got past the first 10 lines. But he did thank me for my ‘copious explanatory notes’, i.e. my return-file letter, which outlined info about the parameters of the index and changes that had to be used.

The prof is going to read the index this weekend, as he’s travelling. I could have had extra days after all! Waah!

Author got back to me with a few queries and the following: ‘Thanks for the painstaking and thorough job – it’s clear you took a lot of care, and I appreciate that … Thanks again for all of your hard work.’

Hopefully he’ll call me again in the future or refer a colleague to me. But after a few days’ reflection and relaxation, I’m not sure I’ll accept such a long and dense manuscript again – unless it truly is strictly names and titles! And I’ve realized that an index you’ve written is more like your baby than a book edit: there’s the same pride of accomplishment, but there’s more of a sense of having created a beautiful thing. And the labour and delivery stories are way better!

Vanessa Wells is a copyeditor, proofreader and indexer who taught Latin for almost 20 years before becoming a freelance editor. When she’s not working, she’s either reading, watching films, or cat-sitting for senior cats with special medical needs. She lives in Toronto, Canada.

www.wellsreadediting.ca

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. FIND OUT MORE > Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader > Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn > Learn: Books and courses > Discover: Resources for authors and editors

This post explores how editors and proofreaders can save time with content marketing by repurposing and recycling existing blogs, booklets or other resources.

Why marketing is sometimes a struggle

Here are two reasons why a lot of proofreaders and editors struggle with marketing:

Here’s an option that will solve both problems. I’m talking about something I bet all of you do rather well, and how you can get some efficiencies from it that will stretch your marketing budget (no Lycra required!). What do you do really, really well? I’ve not yet met one of my peers who couldn’t have a decent conversation with me about editing and proofreading – whether it be a technical or stylistic issue, or a business-development matter. You're all great at it. And if you can talk about it, you can write about it. And if you can write about it, you can offer that information to colleagues and potential clients. And that’s marketing. So, for those of you sitting in the too-difficult camp, you’ve no excuse! And here’s a tip – solving problems is always good fodder for marketing. If you’ve read Marketing Your Editing & Proofreading Business, you’ll recall my discussion of Kevin Daum’s Differentiation–Empathy–Solution framework. The empathy part of the framework is where you identify the problems. The solution part of the framework is … well, it’s pretty obvious! If you’ve read How to do Content Marketing, you’ll recall that I bang on non-stop about solving clients’ problems. So write about all the problems you’ve ever been asked to solve and you’ll not go far wrong in terms of engaging with the audience who asked the questions in the first place. Now we’ve got that out of the way, let’s look at one way you can save yourself time in the long run … Recycling This year I landed a free ticket for the Summit on Content Marketing via content marketing masters Andrew and Pete. One hundred speakers in twelve days. No, I didn’t listen to all of the webinars. And I was up until 1 a.m. frequently, just to catch what I could. But it was worth it because one of the sessions was by Gordon Graham, aka That White Paper Guy. In ‘One White Paper, Five Ways: Stretch Your Content Marketing Budget by Repurposing’, Graham demonstrated how after creating one large, in-depth piece of writing (which can be used as a marketing tool in its own right) you can create additional promo pieces from it by slicing and dicing. More on that later. Now, Graham specializes in the white paper – ‘A persuasive essay that uses facts and logic to promote a better way to solve a business problem’ – but we editorial pros can take the basic principles and use them to create our own problem-solving materials too. Let’s put aside the term white paper and think in terms of booklets instead – ebooklets specifically, since we can post them on a blog and pages of a website, send them out to our mailing list or blog subscribers, email them to colleagues or clients who are looking for answers contained in that booklet, link to them in our social media posts, upload them to our membership forums, and so on. What makes a great booklet? Graham has some wonderful advice on how to approach a white paper, but I think these points are well worth bearing in mind for booklets too. I’m paraphrasing here but it boils down to this:

We’re editors and proofreaders. That’s mostly nuts-and-bolts stuff that editors are paid to look out for, so I’m confident every one of us can do this. Upside-down thinking In the past, I’ve tended to think of my writing upside down. I might create several blog articles and then wonder whether, because they’re related (say, by topic), I can merge them into something more substantive. My first two books emerged, in part, from that mode of thinking. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with that approach. However, it’s not always the most efficient way of doing things; I tend to limit myself in terms of word count and perhaps omit information that I’d like to explore in more depth but choose not to because I don’t want to overload the reader. And then, when I want to create something more substantive, I have to go back and rewrite large chunks of material to ensure the detail’s there. By switching things round and creating the big piece first, I don’t limit myself or my ideas. I can put everything into the booklet, and then decide how best to slice and dice later. Examples of white papers and booklets Here are five examples of in-depth pieces – three from the publishing industry, and two from my own stable:

The slice and dice – a case study

To show you how the process works, and why I think it’s effective, I’m using How to write great sex scenes as a case study, because it’s something that’s on the go at the moment and the process is fresh in my mind. Why am I writing it? Because I’m asked about it A LOT, and it’s something that many beginner authors struggle with. That means it solves a problem. And when we solve problems we’re more likely to be trusted. There are tens of thousands of people in the world offering editing and proofreading services. For the beginner author, with no prior experience of self-publishing, trying to find help can be terrifying. Is X trustworthy? Does Y know what she’s doing? Is Z worth the money he’s asking? When we show we’re engaged with our clients’ problems, we begin to earn their trust, and they’re more likely to ask us to quote. So I’m not only helping my clients, but also helping my business. What do I get out of it? I’m learning. This is the realm of writer coaching and developmental editing. That I’m neither of those things is neither here nor there. The fact is that lots of my clients choose not to hire developmental editors or writing coaches before they come to me. So if I learn, at least I can articulate what their problems are, how they might solve them in their future writing projects, and direct them to expert guidance that I’ve discovered on my own journey. Why don’t I just refer them to existing articles? Because there’s tons of the stuff. And that doesn’t help a beginner author who’s in the very early stages of developing their novel-craft and navigating the self-publishing process. Like all of you, I pride myself on being helpful and solving authors’ problems rather than creating more for them! Besides, I want that content on my website. I want my authors to see that I’m engaged with their problems rather than just sending them to someone else – someone they’ll think is more helpful than me. How am I handling the research? I’m reading a lot (research like a think tank). The advice is always wise, and sometimes hilarious, so it’s a joy to do. And this way I get to summarize the advice of expert writing coaches who know how to write about sex well, and the resources they’ve created. There are entire books about this stuff, you know! And I’ll cite like a scholar. Well, perhaps I won’t be using the full author–date system (I do, after all, want to write more like a journalist and communicate like a human being) but all my sources will be attributed fully in a reference section at the end. What about the format? It’ll be a PDF, but I’ll create a hardcopy-style booklet image for marketing purposes – a bit like this one for the audio-book primer.

I like a landscape format for my booklets because they work well on tablets and laptop screens. But, really, it’s a personal choice.

I’ll create the cover image in Canva (using the principles outlined in an excellent and free Canva Copy Special video and template by Andrew and Pete) using my brand colours and fonts. Then I’ll use that to create a 3D booklet picture with BoxShot 3D (there’s a newer version but I prefer the older one; you can still access it though it’s not supported technically). How long will it be and how long will it take to write? I reckon about 10,000 words max. in total – maybe 9 or 10 sections covering different aspects of the problem. I don’t know how long it will take, to be honest. I tend to write my blog posts and booklets in front of the TV. That way, I’m relaxed and don’t feel like it’s cutting into my spare time. Reading time is something I don’t have trouble fitting into my life – it’s just something that happens, and it’s a pleasure, even when I’m learning. My approach to my marketing and writing is: it takes as long as it takes. It’ll be ready when it’s ready. It might take a week, or a month, or more. It depends what else is going on. My only rule is that I make sure I’m ahead of myself by a couple of months so that I can market my business regularly and consistently with my writing. The thing is, once it’s done, I get to kick back and break out the chopping board! The slice-and-dice-stage Once I have the booklet written and the image produced, I can use it as it is – a substantive, useful and compelling resource that will help current and future clients. But I can also chop it up. If I have 10 different sections, and each one’s around 1,000 words, I can easily create a series of 10 blog posts, each with its own core theme. That’s a lot of useful content to offer potential clients, and I can stagger the publication in whatever way suits me best. Does that detract from the value of the booklet? I don’t think so. It’s about visibility and choice. Regarding visibility, different people find answers to problems in different ways. So they might see my tweet about this booklet and think, ‘That’s useful. I’ll download that.’ But they might also place a longer question into Google, such as ‘How long should a sex scene be in a novel?’ My booklet’s unlikely to show up because its title doesn’t answer that question. But a blog post that looks specifically at that question might well end up in the results. It’s certainly far more likely to than the booklet title alone. As for choice, the thing to remember is that not everyone can be bothered to root around on a blog for Parts 1 to whatever. Blog posts work really well when everything’s in one place, but once you start asking people to jump here, there and everywhere there’s a risk they’ll switch off. What I like to do is slice up the content into several posts but give the reader the option of downloading the full booklet at every stage. Graham also suggests using some of the sliced-off articles as guest posts. This is a great idea because, again, you’re putting your resource in front of a new audience that might otherwise not have seen it. Repurpose and relax Any editor or proofreader can stretch their marketing budget using this recycling method. When we create an in-depth, research-based resource, we help our clients and we teach ourselves. That’s a win–win all round. As long as it’s dripping with value, you should feel free to carve it up in whatever way suits you. Your clients aren’t homogeneous when it comes to finding solutions to their problems, which means you don’t have to be homogeneous when it comes to delivering them. When you slice and dice, and deliver according to your audience’s preferences, you increase engagement, build trust and expand the life cycle of the story you’re telling. What’s not to like? – that’s how I rounded up the discussion of how publishers can stretch their marketing budgets on BookMachine’s blog. I think it stands just the same for the freelance editorial pro. Go on! Write yourself a booklet! Also mentioned

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

‘A good design should be almost invisible. It should support your words, deliver them to the reader, not get in the way.’

Rebecca Brown, Design for Writers

I'm delighted to welcome Rebecca Brown of Design for Writers to the Proofreader's Parlour. Design for Writers is the team I refer my authors to when they ask for help with book formatting and design.

In this post, Rebecca offers her expert advice on how to get the best from your book interior ...

Congratulations! Having shed blood, sweat and tears, and arrived at a finished manuscript, you’ve decided to take the plunge and self-publish.

As part of the process of finding the best people to help you do that, one of your priorities will be making your book look as professional as possible. Everyone’s heard the saying ‘Don’t judge a book by its cover’. Yet most people do just that. And they judge it by how it looks inside, too. The cover will get people to pick your book off the shelf; the interior will help make it a pleasure to read. Why is interior design important? Your words have been carefully edited and chosen to hook your readers, but the best opening lines may never even be read if they’re set in a font that’s difficult to read, the margins are so small that you need to crack the spine just to read the start of each line, or the overall design looks rushed and unprofessional. Many self-published authors rely on online sales of both print books and ebooks though, so, okay, a badly designed book might not necessarily put off all prospective buyers. But do you want your readers to leave reviews saying, ‘I don’t know if this book was any good because it was horrible to read’? It does happen, just as readers will leave reviews that criticize poor editing or a weak story line. And those readers are less likely to return for Book Two. What does a well-designed book look like? The best way of answering that is to look at some professionally published books. This is what you’ll find. Text: The text is large enough to read – usually around 11 or 12 point – but not too large (unless it’s a large-print edition) of course; the point is that the text size is appropriate for the target audience. Margins: There’s plenty of space around the text. You don’t want tiny margins; you need to be able to see the text as it goes in towards the spine, and you need to be able to hold it around the edges without your thumb obscuring the words. Some titles will have bigger margins, like children’s books. Again, it’s about an appropriate design for your readership. Typeface: The most obvious and striking feature is the chosen typeface. It should be a serif font (like Garamond, or Times) not a sans-serif font (like Arial) for the body text. Serif fonts are easier on the eyes for long format, physical text. Sans-serif fonts are easier for on-screen reading on a computer. However, this itself can depend on the type of book – many people prefer a sans-serif for some kinds of non-fiction. For fiction, though, choose a traditional serif font. That way, if you need to make part of the text stand out – for example, if your protagonists exchange text messages, it’ll be more obvious that you’ve made a deliberate style choice, and have a more professional impact. When it comes to print books, small details like embellishments and display fonts for titles all add to the pleasure of reading, and to the sense of your book as a beautiful piece of work. That doesn’t mean you should try to mimic the same experience in your ebook, though …

Print and digital books are different animals Authors often hugely underestimate just how different ebooks and print are. Don’t aim for a duplicate of your print book – it’s a different reading experience. A stand-out feature of ebooks is the extent to which the reader can set up the reading experience to fit their personal preferences (for example, text size, font, and spacing). If you try to force a replica of your print book, you’re doing your book a disservice and making things more difficult for your reader. For example, every ebook device is slightly different, so if you have many different embellishments and beautiful fonts, you’re increasing the risk of the book not displaying as you intended, perhaps not working properly at all. Doing it yourself Authors can, and often do, carry out the work themselves. There are many good guides to setting out your text, and if you bear certain guidelines in mind, such as those mentioned above, you’ll be able to produce a decent book. If your budget is limited, this can be a good option. Bear in mind the following:

Ebook

Hiring a professional

While you can do it yourself, there is a risk that you'll miss out those extra design elements that make your book stand out. Hiring pro interior designers ensures that your files are absolutely guaranteed to work with the major retailers, and that your book will offer your readers the best reading experience possible, regardless of format (e.g. paperback, hardback, ereader). So what should you look for? Price is always a consideration of course. This can be an expensive endeavour, but sometimes you do get what you pay for, and cheaper is not necessarily better. Look for what’s included in the package:

For print, at least, the designer’s use of InDesign demonstrates a level of skill and commitment to using professional tools. Ask to see examples of your prospective formatter work. Find out what books they’ve worked on (from their website or social media, for example) and take a look at the ‘Look Inside’ feature on Amazon, noting the following:

Evaluating the professional designer’s process It’s important to understand how your designer works if you’re to get the best value for your investment. If they’re not interested in getting to know your book and your style, that should be a red flag. Ask them how they would like your manuscript to be sent to them. Most will want final, fully edited text in a common format (such as a Microsoft Word document), but often they’ll allow a ‘reasonable’ number of small changes after proof stage. That’s because designers are human, too! We realize that seeing your work laid out for the first time can alert you to small typos and errors, no matter how carefully you’ve checked it. However, multiple rounds of editing once the text is laid out can have a bigger impact than you might think, so get it as close to finished as you possibly can, and make sure you understand what levels of revision are included by your formatter. Finally, and this goes for any book-publication service, think about your initial contact with them. What are they like to work with? There’ll be quite a lot of back-and-forth. Discussion is important because this is such a personal, important project for you. Having a great rapport with your designer is essential. Good luck! Rebecca’s top tip

Whether you’re doing it yourself or paying someone, keep it simple! Your text is what the reader’s bought, so a good design should be almost invisible. It should support your words, deliver them to the reader, not get in the way.

Design for Writers

For drama-free book design, contact Rebecca or Andrew at [email protected] or www.designforwriters.com

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses. |

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed