|

Is your dialogue pushing your novel forward or making the reader feel like they’re eavesdropping on a mundane conversation at the bus stop? Here’s how to ensure your dialogue pops.

What good dialogue isn’t

Good dialogue is the icing on the cake of a well-structured novel. Bad dialogue will mar a well-structured narrative and bury a story that is barely hanging in there. Before we look at what makes great dialogue, let’s look at what dialogue isn’t:

WHAT DIALOGUE IS NOT

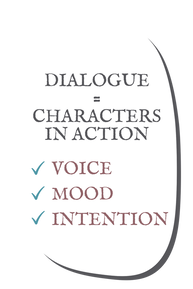

3 components of effective dialogue ‘Dialogue should be the character in action,’ says John Yorke in his must-read Into the Woods (p. 151). Yorke’s talking about the art of screenwriting but the advice is just as pertinent for novelists. I recommend you read it even if you have no intention of writing for the screen because it’s a masterclass in storytelling, whatever the medium. When we stop thinking about dialogue as words spoken – as conversations – and instead frame it in terms of characters, we create something that’s fit for a novel. What does your dialogue tell readers about who your characters are, how they’re feeling, and what their motivations are?

Unreliable dialogue What a character expresses through dialogue need not match their true voice, mood or intent. Unreliable dialogue is powerful precisely because it jars the reader by masking the truth (which the characters themselves may even have buried). Imagine this scenario: John has been kidnapped by Jane. They met in a club where she spiked his drink. He started to feel unwell and she offered him a ride to the Tube station. He never made it. He’s been held captive for several days, during which time he’s been physically abused and deprived of food. He’s frightened out of his wits, and weak to boot. The dialogue between John and Jane could go as follows: John raves and rants, telling Jane her behaviour is monstrous, that Jane’s going to pay for her actions and that he’s going straight to the police as soon as he’s escaped. Jane responds in fury, telling John he deserves it all and how there’s no way he’ll ever escape. Or the dialogue could be unreliable. John might be polite, sycophantic even, as he thanks her for the water she provided, compliments her on her appearance, or asks her about her life. Through that speech, we are shown his desperation. It’s about keeping her on side and calm in order to save himself. And Jane’s verbal response might be chipper, seductive even. Through that dialogue, we are shown her psychosis. The result is a sinister verbal exchange that allows us to explore the inner workings of the characters’ minds without it being forced down our throats via an all-to-obvious narrative that’s centred around the viewpoint character. Breaking free of viewpoint limitations Most novelists opt to hold third- or first-person narrative viewpoints. That means the story in a chapter plays out through one person’s perspective. When authors drop viewpoint, readers end up playing a game of narrative table tennis in which they bounce from one character’s head to another. We know who everyone is (voice), what everyone’s feeling (mood), and what everyone wants (intention) all of the time. Readers become disengaged because they don’t have time to immerse themselves in any one character’s experience. Good dialogue allows writers and readers to break free without head-hopping. Through dialogue, readers can intuit the voice, mood and intention of multiple characters, yet the singular narrative viewpoint remains true throughout. That keeps the reader engaged and the writing taut. Purposeful dialogue in action Here’s an excerpt from Lee Child’s Never Go Back (pp. 457–8). I chose it because I’ve also seen the movie, which allowed me to compare my experience of the screen dialogue (and the advice Yorke gives) with the novel’s, and because there are no action beats, only two speech tags and no narrative. It’s just dialogue between a teenage girl and Jack Reacher.

‘Am I in trouble?’

Reacher said, ‘No you’re not in trouble. We’re just checking a couple of things. What’s your mom’s name?’ ‘Is she in trouble?’ ‘No one’s in trouble. Not on your street, anyway. This is about the other guy.’ ‘Does he know my mom? Oh my God, is it us you’re watching? You’re waiting for him to come see my mom?’ ‘One step at a time,’ Reacher said. ‘What’s your mom’s name? And, yes, I know about the Colt Python.’ ‘My mom’s name is Candice Dayton.’ ‘In that case I would like to meet her.’ ‘Why? Is she a suspect?’ ‘No, this would be personal.’ ‘How could it be?’ ‘I’m the guy they’re looking for. They think I know your mother.’ ‘You?’ ‘Yes, me.’ ‘You don’t know my mother.’ ‘They think face to face I might recognize her, or she might recognize me.’ ‘She wouldn’t. And you wouldn’t.’ ‘It’s hard to say for sure, without actually trying it.’ ‘Trust me.’ ‘I would like to.’ ‘Mister, I can tell you quite categorically you don’t know my mom and she doesn’t know you.’ ‘Because you never saw me before? We’re talking a number of years here, maybe back before you were born.’ ‘How well are you supposed to have known her?’ ‘Well enough that we might recognize each other.’ ‘Then you didn’t know her.’ ‘What do you mean?’ ‘Why do you think I always eat in here?’ ‘Because you like it?’ ‘Because I get it for free. Because my mom works here. She’s right over there. She’s the blonde. You walked past her two times already and you didn’t bat an eye. And neither did she. You two never knew each other.’ WHAT WE LEARN

This is characters in action, expressed through speech. Child makes every line count towards the chapter denouement. If he was tempted to introduce narrative and action beats that ensured we’d get it, it doesn’t show. In fact, they would have been interruptions and slowed the pace. Instead, he trusts us to do the work because the dialogue gives us everything we need. Here’s an excerpt from The Poison Artist by Jonathan Moore (pp. 244–5). I chose this because of the contrast between Kennon and Emmeline’s speech.

“Don’t move,” Kennon said.

This time, his voice wasn’t much more than a whisper. [...] “Inspector, you’ll hit somebody,” Emmeline said. [...] “You look sick, Inspector,” Emmeline said. “I could get you something to drink. A glass of water, maybe? Something a little stronger?” Kennon fired again and Emmeline didn’t even flinch. The bullet missed her by ten feet, punching a hole in the back of the building. “Stop—” “You should be more careful what you touch,” Emmeline said. “Some things can go right through the skin.” WHAT WE LEARN

This, too, is characters in action, expressed through speech. Moore draws us deep into the transgressor’s mind – even though she’s not the viewpoint character. Her dialogue, juxtaposed with Kennon’s exhausted near-silence, generates a powerful scene that oozes with sickly tension. Here’s a third example from Harlan Coben’s Run Away (pp. 68–9):

“The murder,” Simon said. “It was gruesome.”

Ingrid wore a long thin coat. She dug her hands into her pockets. “Go on.” “Aaron was mutilated.” “How?” “Do you really need the details?” he asked. [...] “According to Hester’s source, the killer slit Aaron’s throat, though she said that’s a tame way of putting it. The knife went deep into his neck. Almost took off his head. They sliced off three fingers. They also cut off ...” “Pre- or post-mortem?” Ingrid asked in her physician tone. “The amputations. Was he still alive for them?” “I don’t know,” Simon said. “Does it matter?” WHAT WE LEARN

Again, through speech we see the characters in action. The contrasting voices and moods show us Simon and Ingrid’s different intentions. There’s no need for more than a peppering of supporting narrative. Summing up

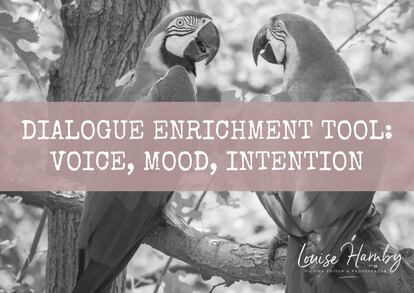

Free dialogue enrichment tool To help you think about your characters' voices, moods and intentions, and how these will enrich your dialogue, download this tool. It's a fillable PDF with ready-made examples and space for you to record your own decisions.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

2 Comments

4/6/2019 12:18:09 am

I tend to assume a character's persona, then speak their dialogue aloud. This might prompt me to use words like 'dame' or 'feral' or 'whyn't'.

Reply

Louise Harnby

4/6/2019 10:07:20 am

Cheers, Maria! That's a great tip for checking whether the *sound* of the voice works once they've ensured the intention/purpose is evident!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed