|

Louise and Denise discuss 5 more tools that will help any editor or proofreader work more efficiently.

|

|

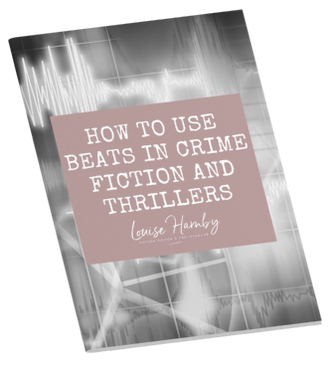

Example from published fiction

Kate Hamer, The Girl in the Red Coat, Faber & Faber, 2015 (Kindle edition, Chapter 6) When I wake up in the morning everything's wonderful. For a moment I can't understand why. Then I remember: Mum's said if the weather's good we can go to the storytelling festival and that's today. |

Description beats

They help readers understand what characters are wearing, what they look like, what’s surrounding them, what they can hear, see, smell, touch or taste. That brings the scene alive.

|

Example from published fiction

Harlan Coben, Win, Arrow, 2021 (Kindle edition, Chapter 1) His name is Teddy Lyons. He is one of the too-many assistant coaches on the South State bench. He is six foot eight and beefy, a big slab of aw-shucks farm boy. Big T—that's what he likes to be called—is thirty-three years old, and this is his fourth college coaching job. From what I understand, he is a decent tactician but excels at recruiting talent. |

Dialogue beats

Like action beats, dialogue is an opportunity to bring depth to non-viewpoint characters in limited narrative styles. Their internal opinions and feelings – which we don’t have access to because we’re not in their heads – are revealed to us.

Why mixing up beats makes scenes more interesting

Writers and their publishing teams can use the drafting and editing stages to analyse the prose and evaluate whether there’s sufficient balance.

How to analyse a scene for beat balance

Approach 1

One way of approaching this is to think not in terms of the different types of beats but instead in terms of what they contribute, and whether there’s too much or too little.

And so writers and their editors can ask: Which of the following should the reader experience in this scene, and are they present? Here’s a summary of those elements:

- Sensibility (via emotion beats)

- Movement (via action beats)

- Breathing space (via inaction beats)

- Stability (via description beats)

- Expression (via dialogue beats)

An over-reliance on dialogue – even if it’s extremely well written – leaves a reader with no nudges about the emotions characters are experiencing or the environment they’re operating in. It’s two or more talking heads on a page.

If there should be expression in the scene, but the characters are chattering too much, think how you might turn the volume down, or at least disrupt it.

Consider introducing a few action, description and emotion beats. Or even turn some of the information contained within the speech into narrative.

An over-reliance on objective description – even if it gives the reader a rich sense of the environment – leaves readers with no way of accessing mood. It’s a menu of what’s where.

Description should stabilise the scene, not crush it so that it’s as flat as a pancake.

Help readers get under the skin of the characters and their environment by adding emotion or dialogue, or a little action that gives the scene some movement.

An over-reliance on emotion can be draining and doesn’t give the reader the chance to take a breath. It’s like a counselling session.

If there should be emotion, but a character’s self-absorption is swamping a reader’s ability to make sense of the environment, introduce description and action beats to ground the reader a little more objectively.

|

Approach 2

Another option is to colour-code the text in a scene according to what type of beats are in play. This can help authors and editors evaluate whether one type of beat is overbearing, and where they might add in additional types of beat to disrupt that dominance. It's a powerful way of communicating the problem visually and quickly. |

Summing up

Other resources you might like

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level: book

- Fiction editing line craft: books

- How to Line Edit for Suspense: multimedia course

- How to Write the Perfect Editorial Report: multimedia course

- Narrative Distance: multimedia course

- Resource library

- Switching to Fiction: multimedia course

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 103

- How Google's algorithm works

- How Twitter's algorithm works

- Why tweeting about content you hate makes it more visible on Twitter and on the web

- Why tweeting about content you hate means you're assisting the creator with marketing

- Using Twitter to elevate the content you love and the causes you care about

Related resources

- Editor Website Essentials (multimedia course)

- Emotional Marketing that Gets Editors Work (multimedia course)

- Marketing Toolbox for Editors (multimedia course)

- Resource library for editors, proofreaders and writers

- Social Media for Business Growth (multimedia course)

Join our Patreon community

Music credit

- Link: https://filmmusic.io/song/4593-vivacity

- Licence: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

What’s in this post …

- What is ‘conscious language’?

- ‘But I’m not part of the “woke” brigade’

- The foundations of editing

- Are you part of the professional editing brigade?

- Why conscious language is also about successful authoring

- Why conscious language is about consideration rather than prescription

- A case study

- Helping our clients

- Tools that help with conscious language

What is ‘conscious language’?

- Who is my audience?

- What tone and level of formality do I want?

- What am I trying to achieve?

- How might history change the impact of my language choices regardless of my intentions?

- Who’s being excluded?

‘But I’m not part of the “woke” brigade’

Oxford Dictonaries defines ‘woke’ as:

Alert to injustice and discrimination in society, especially racism.

Aware of and actively attentive to important facts and issues (especially issues of racial and social justice).

Neither mention that the term is sometimes used as a slur against people who are judged to be overly politically correct, over-sensitive, overly concerned with not offending, overly prescriptive.

So must editors be ‘woke’? How we answer that will depend on what we think editors are supposed to do.

The foundations of editing

Since how we approach language will be influenced by the bubble of our own lived experience, editorial practice requires listening to others who offer alternative insights – ones we were perhaps previously unaware of – into the meaning of words and the consequences of their use.

It means allowing our prior assumptions to be challenged, to consider that what we thought we understood might need revising.

And it means opening our minds to the opportunities that are already alive in the English language – words that explain rather than exclude, and that are rich in both sense and sensibility.

If, like me, you’re not keen on the term ‘woke’ because its negative usage has become a distraction, try an alternative.

My preference is ‘professional editor’.

Are you part of the professional editing brigade?

The professional editor who isn’t alert to wording that distracts from the message rather than amplifying that message isn’t doing the job that a professional editor is supposed to do: being paid to help the author prepare their book for readers.

And so regardless of the editor’s personal opinion on this word or that word, regardless of whether the editor uses the term ‘woke’ to describe their mindset or to cast a slur, there’s a business case for conscious language.

The professional editor can’t sidestep that because it’s not about us, and it’s not our book. It’s about the author, and it’s their book.

Why conscious language is also about successful authoring

Most authors want to sell as many books as they can. That means engaging as many readers as they can. Engaged readers focus their attention on story. Novels containing words and phrases that distract from story, rather amplifying it, don’t serve authors.

Deliberately reviewing novels for words and phrases that might disengage a chunk of the potential readership is therefore nothing more than good commercial practice, and it’s the editor’s job to support the author who’s striving to create something that will give them a return on their investment.

Why conscious language is about consideration rather than prescription

The meaning we attach to some words might differ depending on, for example, where we live, how old we are, and how we’re racialised, sexualized and gendered by others. In other words, what I mean when I use a word might not be what you mean when you use that word.

My author is a white British man. I know very little else about his identity but I’ve line edited two books for him and thoroughly enjoyed every moment. In the second project, a viewpoint character uses the word ‘thug’ to describe an unpleasant minor character.

In Britain, the word ‘thug’ isn’t racialized (at the time of writing and as far as I’m aware) – meaning the term isn’t typically assigned to a particular racial group. That’s not the case in America, where, I’ve learned, the term is heavily racialized.

My author is British. His characters are British. His book’s setting is Britain. The term ‘thug’ in that context therefore doesn’t jar … as long as we view the project within that bubble of author–character–location.

However, that’s potentially problematic. There’s something missing from that bubble: the people who’ll determine whether my author’s book is a commercial success – readers.

My author’s keen to sell his books all over the world, including into America, and for that reason I suggested some alternatives to the word ‘thug’, and explained why I think he’d do well to choose one of them.

The choice was his because it’s his book. And he decided to heed the guidance because both books I’ve worked on have explored the impact of predatory behaviour and abuse.

He writes with compassion and mindfulness, and says he doesn’t want to include a word in his book that might distract one of his American readers unless it’s critical to the character’s arc. And in doing so he's considered:

- who his audience is

- what he's trying to achieve

- how history AND geography affect the impact of his language choices regardless of his intentions

- those who might be excluded if he weren't to consider other options.

Helping our clients

A conscious-language approach to editing therefore helps us to help our clients. We can share the knowledge we’ve acquired from our colleagues in the publishing community, knowledge that our authors might not be aware of.

And in doing so, they can publish a book that keeps its audience wanting to turn the pages rather than rip them out.

Summing up

That doesn’t mean we have to know it all – we can’t, not least because the language landscape is always in flux. It does mean we have to be ready to listen, learn, and advise so that our clients can make informed – conscious – decisions.

And we don’t have to do it alone. There’s a large and diverse community of editors and writers who are with us on that journey, and tools to help us improve our practice.

Tools that help with conscious language

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 102

- Writing regularly

- Niche target audiences

- Building a reader base

- Authority and credibility

- Timeliness considerations

Related resources

- Branding for Business Growth (multimedia course)

- How to Earn Passive Income (book)

- Writing resources

Join our Patreon community

Music credit

- Link: https://filmmusic.io/song/4593-vivacity

- Licence: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

In this post ...

- What a dialogue tag is

- Back-loaded tags

- Mid-loaded tags

- Front-loaded tags

- Impact level, psychic distancing and lyricism in front-loaded tags

What a dialogue tag is

- Are you enjoying reading that blog post?’ Louise said.

- ‘Are you enjoying reading that blog post?’ she asked.

In the above examples, the tags are shown in bold and comprise the subject (someone’s name or their pronoun) doing the speaking, and the verb from which the reader can infer that the action of speech is taking place.

Commonly used effective verbs include ‘said’, ‘asked’, ‘replied’, ‘whispered’, ‘muttered’, ‘yelled’, ‘continued’ and ‘added’.

Ineffective dialogue tags use verbs that bring to mind action that’s not related precisely to speech but to some other behaviour. Examples include ‘sneered’, ‘grimaced’, ‘laughed’, ‘harrumphed’, ‘huffed’, ‘sighed’, ‘snarled’ and ‘urged’.

Positioning tags in fiction:

Back-loading, mid-loading and front-loading

So where might they go?

Dialogue tags can be front-loaded, mid-loaded and back-loaded.

Back-loaded dialogue tags

Back-loaded tags come after the speech and are used commonly. Consider using them in the following circumstances:

- Length of dialogue: Your character’s dialogue is a short burst and you want to ensure the reader’s attention is focused on what’s being said straightaway, rather than who’s saying it.

- Impact level: The dialogue is relevant but low key. There’s no punchline that might be flattened by a tag.

EXAMPLES

Mid-loaded dialogue tags

Mid-loaded tags come between the speech. They, too, are a popular choice for writers. Consider this option in the following circumstances:

- Length: The dialogue stream is longer and you want to ensure your readers don’t wait too long to discover who’s speaking.

- Rhythm and context: You want to introduce a natural pause so that the speech doesn’t turn into a monologue. You can also supplement the tag with descriptive action that grounds the dialogue in the environment and helps the reader picture the scene.

- Impact level: You’ve written a witty, suspenseful or impactful punchline into the dialogue and don’t want it interrupted or flattened by a tag.

- Interrupted speech: You’ve written speech that’s interrupted abruptly and don’t want the tag interfering with the interrupter’s speech.

EXAMPLE 1

This first example is from David Rosenfeld's Collared.

Notice how in the above example of single-character dialogue, which comprises a total of 51 words, the impact point is with the closing sentence: ‘Sign the damn form and send it in’. Because the tag’s located earlier, that dialogue gets to shine.

Compare the original with this version, which I’ve given a back-loaded tag:

Back-loading the tag strips ‘Sign the damn form and send it in’ of its oomph.

EXAMPLE 2

Here’s an example from Linwood Barclay’s Parting Shot that shows how mid-loaded tags can protect the flow of interrupted dialogue.

Notice how by mid-loading the dialogue tag, Ms. Plimpton’s interruption – indicated by the closed-up em dash at the end of Duckworth’s speech – feels more authentic because it’s given the space to flow.

Front-loaded dialogue tags

Front-loaded tags come before the dialogue. This position is the one least used in most commercial fiction, and there’s a good reason for that: reader focus.

Those familiar with advice on writing for the web will know that web copy needs to be front-loaded with relevant keywords. This means that the important stuff comes first. That’s because visitors to websites are busy and scanning for solutions to their problems. When they don’t get them fast, they become frustrated and are more likely to jump to another site.

If the novelist’s done their job well, readers will invest way more time in soaking up their prose than if they were shopping for a new duvet cover. Even so, every word in a piece of fiction needs to count, and readers should still be focusing on the most important stuff.

And so if you’ve written great dialogue, most of the time you’ll want to ensure your readers are focusing on it as soon as possible. Front-loading the speech, rather than the tag, helps achieve that.

That’s not to say that front-loaded dialogue tags don’t have their place. They do, and they can be extremely effective when used purposefully.

When front-loaded tags work:

Impact level, psychic distancing and lyricism

Impact level

A front-loaded dialogue tag can function in the same way as a mid-loaded one when it comes to speech containing impact points. Again, we’re talking about dialogue that’s witty, suspenseful, or closes with an impactful line that you don’t want to flatten with a tag.

EXAMPLE

Let’s return to the excerpt from Collared. Although Rosenfelt uses a mid-loaded tag, he could have opted for a front-loaded one and preserved the oomph in his closing sentence. Here’s how it might look:

Psychic distancing

If you want the prose to feel more expository so that the reader is less closely connected to the character, front-loading the tag might be just the ticket. Doing this widens the psychic (or narrative) distance.

A tag tells of speaking whereas dialogue shows what’s being said. By placing the tag first, you draw the reader away from the character’s voice and give the prose a more objective feel.

EXAMPLE

This excerpt is from Jens Lapidus’s Life Deluxe.

|

They veered onto a side street off Storgatan.

Jorge's phone rang. Paola: "It's me. Que haces, hermano?" Jorge thought: Should I tell her the truth? "I'm in Södertälje." "At a bakery?" Paola: J-boy loved her. Still, he couldn't take it. He said, "Yeah, yeah, ‘course I'm at a bakery. But we gotta talk later—I got my hands full of muffins here." They hung up. |

Lapidus has front-loaded dialogue tags and thoughts in this excerpt, and it’s an excellent example of psychic distancing in action. The centring of the characters rather than the speech gives the prose a detached, clinical feel that shows rather than tells mood.

Jorge is a drug-dealer operating in Stockholm’s shady underworld. He’s only just out of jail but already he’s frustrated with a life of honesty. In fact, he’s got only one thing on his mind: easy money.

The wider psychic distance means we get to see the world through Jorge’s eyes but without getting too close to him. Perhaps Lapidus doesn’t want us to empathize with him too much. Instead, he widens the psychic distance just enough that we can make up our own minds about whether Jorge deserves the trouble coming his way.

Lyricism

Repeated use of front-loaded tags with short bursts of dialogue can introduce a lyricism into prose whereby the tags function as more than just indications of who’s speaking. They become part of the poetry.

This approach can work particularly well with parody, satire and comedic prose.

EXAMPLE

Mari said, ‘No.’

Ahmed said, ‘Yes.’

Sol said, ‘Maybe.’

Dave said, ‘I couldn’t give a shit. Is that the best you’ve got?’

Arthur said nothing, just yawned.

The bell rang. Suitably insulted, I raised the SIG, shot each student in the head, and retired to the staff room.

Notice how the multiple front-loaded dialogue tags are performing anaphorically. Anaphora is the purposeful repetition of words or phrases at the beginning of successive clauses.

It’s often used in poetry and speeches. When it’s used in novels, that repetition draws the reader's eye and can show rather than tell mood – boredom, monotony or, as in this case, disinterest. The tags are therefore key to the lyricism, and as important as the speech.

Summing up

The key is to consider what purpose your tag is serving and how it can best amplify the speech, evoke mood, and improve rhythm.

Cited sources

- Barclay, l., Parting Shot, Orion; 2017 (p. 380)

- Boyd, W., Solo: A James Bond Novel, Vintage, 2014 (p. 260)

- Crosby, SA, Blacktop Wasteland, Headline, 2021 (Chapter 1, Kindle edition)

- Lapidus, J, Life Deluxe, Pan, 2015 (Chapter 1, Kindle edition)

- Rosenfelt, D, Collared, Minotaur Books, 2017 (Kindle edition)

Fiction editing training: Books and courses

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level (book)

- Fiction editing and writing resources (online library)

- How to Line Edit for Suspense (multimedia course)

- How to Write the Perfect Fiction Editorial Report (multimedia course)

- Narrative Distance: A Toolbox for Writers and Editors (multimedia course)

- Preparing Your Book for Submission (multimedia course)

- Switching to Fiction (multimedia course)

- What is anaphora and how can you use it in fiction writing? (blog post)

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 101

- Booklets that perform like gifts

- Papers that offer authoritative analyses

- Audio that creates emotional connections

- Video that demonstrates how-to solutions

- Blog posts that make you findable

Related resources

- Blogging for Business Growth (multimedia course)

- Editor Website Essentials (multimedia course)

- Marketing Toolbox for Editors (multimedia course)

- That White Paper Guy

Join our Patreon community

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 100

- Creating an episode – what's involved

- How long podcasting takes

- Efficiency strategies

- Working with a partner

- The costs of podcasting

- Accessibility challenges

Related resources

- Captivate (affiliate link)

- Audacity (free audio editing software)

- Editorial marketing resource library

- Editorial branding resource library

- Blogging for Business Growth (multimedia course)

Join our Patreon community

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

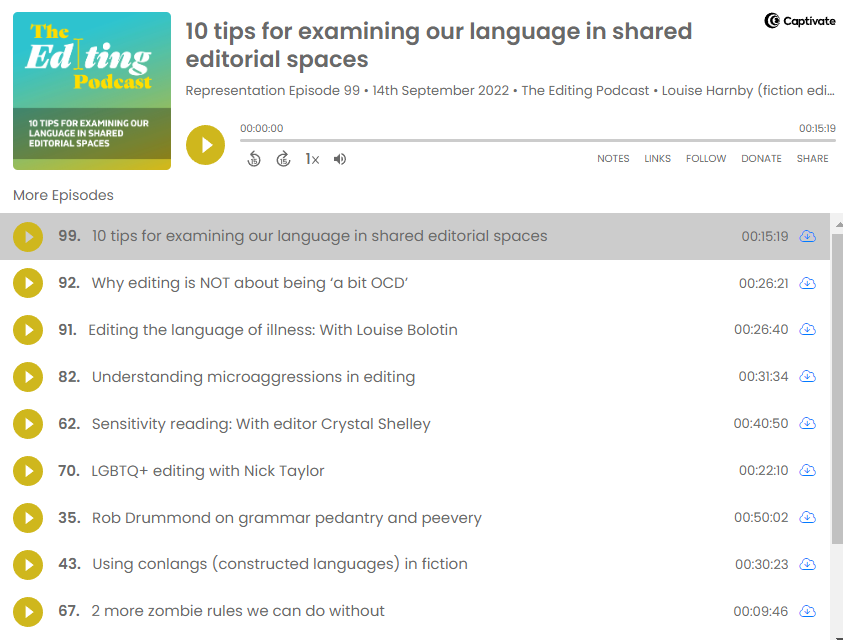

Summary of Episode 99

- Familiarising ourselves with the rules of that space

- Acknowledging that our political, professional and ideological positions are not going to be the same as everyone else’s

- Recognizing the potential diversity of our editorial spaces

- Saying hello and introducing ourselves first

- Being prepared to be challenged

- Owning our words if we're challenged

- Acknowledging that intention not to hurt doesn’t absolve us of the responsibility for that hurt.

- Being prepared to feel uncomfortable

- Accepting our privilege without getting our knickers in a knot!

- How it's for the white, cis, straight etc people to do the work

Related resources

Join our Patreon community

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 98

- how professional standards are defined

- why they’re important for editors and proofreaders

- who’s setting them

- the tools some organisations are using to set standards and ensure that

- editorial practitioners demonstrate and uphold them.

Related resources

Join our Patreon community

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

What’s in this post …

- Your online course and the tax authority in your own jurisdiction

- Your online course and the tax authority in other jurisdictions

- Finding a taxation-friendly training platform

- Understanding Merchants of Record

- Where I host my editorial training courses

- Summing up: What to consider

Your online course and the tax authority in your own jurisdiction

Not all digital services and products are created equally, and the rules in one country might be different in another. Even within a single jurisdiction, your online course might be treated differently in terms of tax depending on how you provide access to the content.

5 examples of online courses

Imagine you’re me, a UK resident offering online training courses. Here’s what the classifications might look like (though I’m no tax specialist) in 2022.

|

Online editing training course

|

Classification in UK

|

VAT must be charged to UK customers?

|

|

EXAMPLE 1

|

Digital service

|

Yes

|

|

EXAMPLE 2

|

Not a digital service

|

No

|

|

EXAMPLE 3

|

Probably not a digital service

|

Probably no

|

|

EXAMPLE 4

|

Possibly not a digital service

|

Possibly no

|

|

EXAMPLE 5

|

Nebulous

|

Nebulous

|

Your online course and the tax authority in other jurisdictions

Anyone offering online courses in a global market must know where their customer lives. And it’s the tax authority’s rules in the customer’s jurisdiction that determine whether we need to add a consumption tax to the price.

Which can be a monumental barrier for sole-trading editors and proofreaders. Why? because here's what we need to take responsibility for.

Our consumption tax responsibilities

Small-business owners selling digital products and services internationally must have a mechanism in place to:

- ensure that our customers provide the necessary jurisdiction data on our invoices

- allow our customers to exempt themselves from the tax where appropriate

- calculate the appropriate tax rate for every customer

- review that tax rate regularly (because they change!)

- collect the tax from the customer

- remit the collected tax to every single relevant tax authority. That's right. Every single one.

That list is enough to deter any small-business owner from sharing their knowledge and charging for it. Which is a crying shame because the editorial community is passionate about training and CPD.

And the fact is that most of us don’t have the time or skills to do this work – unless we decide we're not actually going to be editors and trainers anymore, but full-time accountants instead.

Nor can we afford to hire an expensive specialist tax accountant who will do this for us – unless we want the entire exercise to become unprofitable.

So what do we do?

The solution: Find a taxation-friendly training platform

What is a Merchant of Record?

A Merchant of Record is the legal entity that usually:

- calculates the appropriate rate of tax that needs to be added to a purchase of your course

- updates that rate of tax rate in your payment gateway when necessary

- collects that tax from your customer

- remits it to the tax authority in the appropriate jurisdiction.

When we choose a training platform that acts as the Merchant of Record, or includes a third-party integration that does the same, that leaves us free to get on with the business of editorial training rather than worrying about whether we’re tax compliant in every part of the world we’re selling to.

If the platform doesn't offer that, we're the Merchants of Record, and the buck's back with us.

What’s on offer?

Some training platforms are partial Merchants of Record. PayHip, for example, calculates, collects and remits VAT in the UK and Europe for me as a UK resident. However, I’m responsible for the tax compliance in all other jurisdictions ... Cue the worry.

Some training platforms include integrations that calculate the tax but don’t collect or remit it. That’s on us or our (expensive) specialist tax accountants. LearnWorlds is an example. The Quaderno app calculates what we owe to whom, but we have to do the rest ... Cue the worry.

Some training platforms act as full Merchants of Record, meaning they calculate, collect and remit all the tax for all jurisdictions. Teachable is an example ... And relax!

Where I host my editorial training courses

- It acts as a full Merchant of Record, meaning I can focus on course creation rather than worrying about tax compliance.

- The platform is super user-friendly for me and my students.

- Teachable has a gorgeous app (iOS and Android), which is fantastic for students who want mobile access. Download it from your usual app store.

- I can brand my content appropriately.

- Multiple editorial trainers use Teachable, which means students can access our schools via a single platform.

- I can now offer payment plans that allow my students to spread the cost.

- And there's a bundles option that lets me offer you access to multiple courses ... and with big discounts!

Note that at the time of writing, trainers wanting to offer PayPal as a payment gateway in Teachable must set their course prices in US dollars.

Teachable is right for me, but any editor or proofreader embarking on online course creation should do their own research. Most platforms offer a free trial so you can get a feel for the setup, functionality and branding options.

Summing up: What to consider

- Creating and delivering online courses for editors and proofreaders has never been easier thanks to the growing number of platforms with user-friendly interfaces and multimedia functionality.

- What’s not so easy is the tax-compliance element. Many of the providers haven’t yet woken up to the implications for small-business owners operating in a global marketplace with complex and ever-changing tax rules.

- If you’re planning to teach online, make sure you understand the differences in tax rules for courses with a live component and courses that are self-directed, not just in your own jurisdiction but elsewhere too. Also bear in mind that what constitutes live tutoring might be nebulous.

- And, finally, if you decide to head down the self-directed training route, and your preferred platform isn’t offering a full Merchant of Record service, think carefully about who’s going to do that work and how much it will cost.

Related resources

- Check out my courses, their payment plans, and discounted bundles.

- Visit my Skills and training resource page to access free guidance.

- Find out how to log in and access courses you've already purchased.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 97

- Why even experienced editors need to learn

- How to use a conference to make a contribution to the profession

- Meeting other editors

- Having fun with colleagues and friends

Related resources

- 6 tips to help you speak in public with confidence. By Simon Raybould

- Editorial training without borders: Should you bother with international editing conferences?

- Organizing an editorial conference. With Beth Hamer

- Speaking at editing conferences: How to do it and love it

- Why editors and proofreaders should be networking

Join our Patreon community

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 96

- What's distinctive about editing crime fiction and thrillers

- What a good line editor needs to look out for

- What new entrants to the field need to study

- Marketing ideas

- Top tips for being a successful freelance editor/proofreader

- Do fiction editors use style guides?

Related resources

Join our Patreon community

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 95

- How it requires a lot of hard work to build and sustain a proofreading business

- Why having periods of no work isn’t something you have to accept as given

- Why grammar- and spell-checking technology hasn’t made proofreaders redundant

- How it’s a myth that all proofreading work is done in-house

- How proofreading means the different things to different client types

- Whether word of mouth is a good enough promotion strategy

Join our Patreon community

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 94

- Getting work even if you don’t have contacts in the publishing industry

- The market for proofreading

- Why training courses are a worthy and essential investment

- Why training in itself isn't enough to get work

- Why you can still build a proofreading career without former editorial experience

- What you might earn

Join our Patreon community

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 93

- Rotating the page view

- Using the ‘Show Cover View in Two Page View’ function

- Attaching a Word file for large amounts of corrected text

- Why you should avoid using ‘floating’ sticky notes

- How to find invisible errors you know you’ve corrected

- Free versus paid-for software: Is Adobe Reader DC good enough for PDF proofreading?

Join our Patreon community

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

What’s included in this post

- What are parentheses?

- Parentheses as convention breakers

- Parentheses as satirical and viewpoint-switch markers

- The question an author posed

- Why parentheses can convey simultaneity

- How readers process sentences in a linear fashion

- Showing sensory assault through simultaneity

- Showing conflict through simultaneity

What are parentheses?

This is what they look like: ( )

Dashes and commas can perform the same function in fiction. Take a look at these examples:

|

Parentheses

|

Tell me about parentheses (round brackets) and how they work.

|

|

Commas

|

Tell me about parentheses, round brackets, and how they work.

|

|

Spaced en dashes

|

Tell me about parentheses – round brackets – and how they work.

|

|

Closed-up em dashes

|

Tell me about parentheses—round brackets—and how they work.

|

Parentheses as convention breakers in fiction

This might be because they’re large and therefore visible marks – ones that demand a reader’s attention. That they’re interruptive could be a good reason to avoid them, though it could equally be the very reason why you want to use them.

The key to using any punctuation mark effectively is to understand its purpose and consider how the reader will interpret it. And so just because the use of parentheses is infrequent enough in fiction to make it unconventional isn’t a reason to ban them from prose.

Parentheses as satirical and viewpoint-switch markers

- For satirical purposes – an external narrator wants to poke fun at a focus character’s behaviour, thoughts or dialogue.

- For viewpoint purposes – the narrative is written from a viewpoint character’s perspective and therefore limited to their experience, but an external narrator wishes briefly to interrupt.

If you’d like to explore my analysis of these two uses, read How to use round brackets (parentheses) in fiction writing.

Scroll through the comments on that post and you’ll see a fantastic question raised by a reader that got me thinking about parentheses again.

The question an author posed

‘Louise, I'm writing a short story in which I have inserted a couple of parenthetical phrases (I don't even know what to call them) which separate one part of a sentence from another. I've seen Stephen King do this and it fascinated me. The character (narrator) is reflecting on a dream she has just awoken from. What do you think of this style, and what is it called?’

I replied admitting that I didn’t know quite what this is called in terms of literary style but that she’d got me thinking, and helped me consider a third function of parentheses that I hadn’t interrogated before: simultaneity.

Here’s her example. It’s from a short story tentatively titled ‘The Woman at the Window’.

(the bombs bursting in air)

bombs that were dropping by the hundreds from a fiery sky.

There are a couple of interesting things going on in Ellen’s example – not just the parenthetical phrase but also the placement of it. It takes its own line, which makes it stand out even more.

Why parentheses can convey simultaneity

‘I wanted to shake the reader up a bit by writing it that way,’ she told me.

And she succeeded. Parentheses do stand out. So does the separate line. But my reading of her work led me to consider another effect she’d created, albeit unwittingly – simultaneity.

How readers process sentences in a linear fashion

This is linear description. We absorb the story in the order the phrases are presented to us – first the dreaming, then the waking-up on a night just before Labor Day, then the terrified screaming, then seeing the exploding missiles, then the glare of the rockets, and finally the flaming sky.

But actually, that’s not how Ellen wrote it. Here’s the unedited version:

(and the rockets' red glare)

and the sky alight with flames.

The rocket-glare phrase is now bracketed and takes its own line. And I think this changes that linearity subtly. It’s as if the glare of the rockets is experienced at the very same moment that the missiles are exploding. It’s another layer of experience that sits behind the explosions.

That’s how we often experience traumatic events in reality. Our brains work so fast that we process multiple pieces of information and feel multiple emotions all at once. The difficulty comes in expressing that in linear text.

In Ellen’s example, the parentheses act as a signal of this simultaneity of experience, and show rather than tell an onslaught of emotional, auditory and visual information.

Showing sensory assault through simultaneity

(the bombs bursting in air)

bombs that were dropping by the hundreds from a fiery sky.

The way the parenthetical phrase punctuates the prose makes me feel uncomfortable. It jars me visually. And that’s why I love it. It shows rather than tells the assault on the senses that I can imagine a person would experience if they were in an environment where missiles were exploding and falling around them.

The character awakes. She’s likely still shaken from the dream, and trying to process what she experienced. And so she narrates what she saw, which pared down is this:

But as she's thinking about this, the bursting bombs is there too, behind the more expository narration, right at the same time. And it’s the bracketed line that shows this.

An alternative might have been:

In that revised version, 'as' tells the simultaneity. It's told prose. Instead, Ellen as author, has shown us with the parentheses, and it's far more dramatic.

And so we might consider parenthetical statements such as this as devices that help authors create layers of simultaneous experience that are warranted when there’s sensory assault in play.

Showing conflict through simultaneity

Here’s an example that I have written more conventionally, using italic and a tag to convey a thought.

Say no, she thought. You don’t have time.

Yes yes yes yes, she typed, because it would be a crap ton of fun and the alternative was D asking someone else, and that was unthinkable.

This approach encourages the reader to approach the prose in a linear way: First D texts Louise with an idea. Then a thought process takes place. Then Louise responds.

But look what happens when we experiment with parentheses.

(Say no. You don’t have time.)

Yes yes yes yes, she typed, because it would be a crap ton of fun and the alternative was D asking someone else, and that was unthinkable.

Now there’s a signal that two conflicting emotional responses are in play simultaneously. Thinking ‘no’ and typing ‘yes’ are occurring at the same time.

Summing up

However, used purposefully, parentheses can enhance that moment and create a sense of simultaneity of experience – perhaps involving an assault on the senses or competing emotions fighting for primacy in a character’s mind.

There are no rules in fiction. Instead, what writers (and the editors who work with them) must strive for is how best to communicate a character’s emotions, perception and actions in the moment, so that the reader can get under the skin of that experience.

And it might just be that – once in a while – a pair of round brackets helps with that goal.

Other resources you might like

|

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 92

- The difference between character traits of orderliness and the lived experience of OCD

- What is OCD and how does it affect people?

- Why OCD is a noun and what that means for how we use the term

- How OCD might manifest

- How flippant and colloquial references to OCD diminish lived experience

- Intention versus perception of harm

- Editing text: querying rather than prescribing problems and solutions

- Does fiction offer more scope for use of harmful language?

- Alternative words and phrases

- Helping clients create engaging rather than distracting messages

Join our Patreon community

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

What’s included in this post

- What a blog is

- How the search engines find blog content

- Why there’s no such thing as an ‘old’ blog post

- Historical record or a reflection of your business’s values?

- What about content written by guests?

- How you might update your blog content

- Might you tag out-of-date posts as archive material instead?

What a blog is

Just like other web pages on your site, blog posts include an H1 heading (the blog-post title) and text. You can add additional headings, buttons, links and other audiovisual material, as well as SEO-friendly meta data and alt-text in images to improve accessibility.

Unlike other pages on your site, blog posts are organized in a way that makes the content more accessible for readers, perhaps via some or all of the following:

- A single point of access to multiple pages

- A topic-based archive

- A date-based archive

- A keyword archive

- A search tool

- The date the content on the page was published

- The option for readers to comment on the page’s content

How the search engines find blog content

The likes of Google don’t give a damn about:

- when you published the content

- whether you’ve changed your opinion since you created the content

- or whether the language you’ve used in a ten-year-old post is language you wouldn’t use now because you’re more aware.

What they are interested in is whether you’ve published content that’s relevant to a search query. So a blog post with keywords and phrases that align with a user’s query will rank higher in the search results.

They’re also interested in how long users stay on that page, and what they do when they leave it. When people stick around on a particular page, that’s a signal that you’ve offered a good user experience.

And if you create links from a blog post to other pages on your website (for example, another blog post, a resource library or your editorial services page) that a user finds interesting and so doesn’t bounce out of your website, that’s another indication that you’re providing relevant solutions to the searcher’s problems.

The more relevant pages you have on your site, the more likely they are to be listed higher up the results of a search query, and the more likely you are to be visited by that ideal client who clicks through.

Why there’s no such thing as an ‘old’ blog post

In that sense, there’s no such thing as an ‘old’ blog post. Remember, Google doesn’t care about the date of publication; it cares only about how relevant your content is to a search query.

The question editor bloggers therefore need to ask themselves is: Do you want people finding content on your business website that

- is out of date, or makes you appear to be out of step with your profession

- uses language that you wouldn’t dream of using now

- or offers advice that you’ve long since revised your opinion on?

If the answer’s no, it’s critical that you frame your blogging mindset in terms of ‘what’, not ‘when’.

Historical record or a reflection of your business’s values?

That’s because we don’t consider our contact, services or home pages to be historical records of what once was. Rather, the content on those pages reflects our business as it is now.

The same applies to a blog. This is merely a collection of other web pages on your site, and so it needs to be treated similarly. Every blog post needs to be regarded as if it were published yesterday.

Blog content is therefore current. That content is a reflection of your business and your brand values as they are today.

Even if that content was published ten years ago.

Certainly, some written materials are historical records – a journal article published in 1969, the first edition of a book, the minutes of a meeting – but editors' blogs are not.

And so if you have blog content on your website that doesn’t reflect your business brand as it is now, it’s time to update it.

Your website is your business shop front, the digital land that you own and control. And you have a duty to preserve its integrity.

What about content written by guests?

YOUR platform.

It’s still your land, your business shop front, and it’s you, not your guest, who is responsible for that space. You therefore still have the right to preserve your website’s integrity. And if that means some sort of intervention, so be it.

If you’re now uncomfortable with the content – even though you weren’t when you published it – decide on the most appropriate way to ensure it reflects your business’s brand values.

How you might update your blog content

Revision

You might choose to edit existing content so that it’s up to date and accessible.

Revision’s a great option for posts that rank high in the search engines for particular queries, and drive potential clients to your website. You get to keep your findability but ensure your existing brand is intact.

Do make sure these valuable posts link to other relevant content on your website.

Deletion

You might decide to delete entire posts, thereby removing those web pages from your site.

Deletion’s a good option for the following types of blog content:

- Posts that are never found and never read.

- Posts that are so out of date that they could damage your business brand.

- Posts that are no longer relevant, for example a review of a book, course or piece of software that’s no longer available.

Repurpose

You might decide to rewrite, using the same theme but bringing your current experience into play.

Repurposing’s a good option for when your original blog post tackled a theme that’s relevant to the kind of people you want to visit your website, but you need a complete rewrite to ensure the content’s bang up to date and reflects your editorial business’s brand values.

Might you tag out-of-date posts as archive material instead?

And website visitors often scan content, and so likely won’t notice the date or an archive marker. Instead, they’ll search for the solution they originally came to the post for.

If that material’s out of date, the damage is done because what they're reading isn't reflecting your current brand values.

There are online online archives, and those serve a purpose, but that’s not the purpose of your editorial blog. Your blog posts, like every other page on your website, should show potential clients why you’re a great fit for each other now.

Summing up

- who we are

- what we do

- what we stand for

- and how we can help them.

Every single web page on our site needs to reflect that messaging. And since blog posts are just web pages, they should be current and relevant. Out-of-date blog content screams out-of-date business. That has no place in any editor’s marketing strategy.

And the date a blog post was published is irrelevant because that’s not what determines its findability. It’s relevance to a search query is what makes it visible. And if it’s visible, it’s visible now.

Happy revising!

Related training resources

|

Editor Website Essentials: Find out how to craft a visible, loveable editorial website with this 10-step framework that takes you through the essentials of SEO, navigation, structure, visitors, UX, branding, web page copy, home page design, content and analytics. Find out more about the course.

|

|

Blogging for Business Growth: Learn how to create a discoverable, captivating and memorable blog that drives website traffic, increases visibility in the search engines, and generates editing work. Find out more about the course.

|

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 91

- Louise Bolotin's cancer diagnosis

- Why the language preferences of those with terminal illnesses aren't homogenous

- Terms in the language of illness that can hurt and harm

- Why editors have a duty to challenge normative narratives that sugarcoat dying and death

- How asking how a person wants to talk about terminal illness is better than assuming

Louise Bolotin's Facebook and LinkedIn statements

- Facebook: The Last Hurrah album

- Facebook: Statement about cancer diagnosis and language

- LinkedIn: Announcement about cancer diagnosis and language

Join our Patreon community

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Summary of Episode 90

- What the different types of editors do in media publishing

- The differences between subediting and copyediting

- Editorial timescales for subeditors

- Who controls the content

- When things go wrong - legal responsibilities and insurance

- Subediting lingo

- A subeditor’s typical day

- Transferring from copyediting to subediting - training and CPD

- Core resources for the budding subber

- How editing has changed over the years, especially for freelancers

Resources mentioned in the show

Join our Patreon community

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

BLOG ALERTS

TESTIMONIALS

Dare Rogers

'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'

Jeff Carson

'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'

J B Turner

'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'

Ayshe Gemedzhy

'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'

Salt Publishing

'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'

CATEGORIES

All

Around The World

Audio Books

Author Chat

Author Interviews

Author Platform

Author Resources

Blogging

Book Marketing

Books

Branding

Business Tips

Choosing An Editor

Client Talk

Conscious Language

Core Editorial Skills

Crime Writing

Design And Layout

Dialogue

Editing

Editorial Tips

Editorial Tools

Editors On The Blog

Erotica

Fiction

Fiction Editing

Freelancing

Free Stuff

Getting Noticed

Getting Work

Grammar Links

Guest Writers

Indexing

Indie Authors

Lean Writing

Line Craft

Link Of The Week

Macro Chat

Marketing Tips

Money Talk

Mood And Rhythm

More Macros And Add Ins

Networking

Online Courses

PDF Markup

Podcasting

POV

Proofreading

Proofreading Marks

Publishing

Punctuation

Q&A With Louise

Resources

Roundups

Self Editing

Self Publishing Authors

Sentence Editing

Showing And Telling

Software

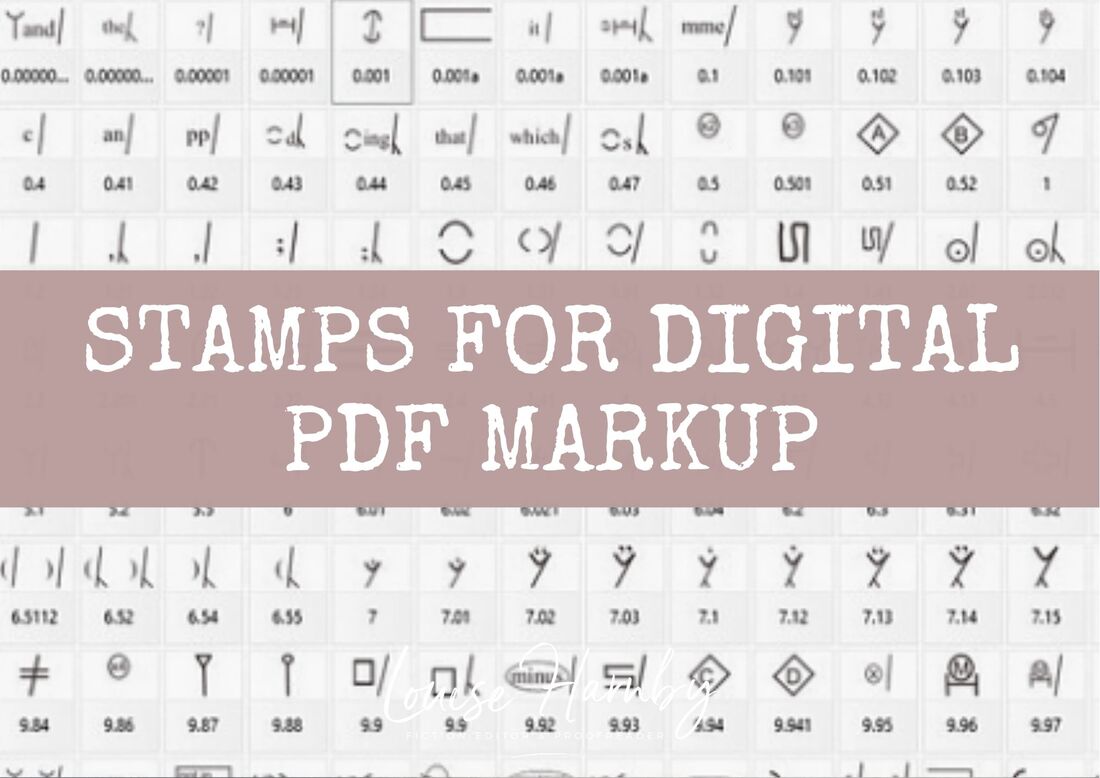

Stamps

Starting Out

Story Craft

The Editing Podcast

Training

Types Of Editing

Using Word

Website Tips

Work Choices

Working Onscreen

Working Smart

Writer Resources

Writing

Writing Tips

Writing Tools

ARCHIVES

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

October 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

October 2016

September 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

March 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

November 2015

October 2015

September 2015

July 2015

June 2015

May 2015

March 2015

February 2015

January 2015

November 2014

October 2014

September 2014

August 2014

July 2014

June 2014

March 2014

January 2014

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

August 2013

June 2013

February 2013

January 2013

November 2012

October 2012

September 2012

August 2012

July 2012

June 2012

May 2012

April 2012

March 2012

February 2012

January 2012

December 2011

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed