|

In this episode of The Editing Podcast, Louise Harnby and Denise Cowle talk to editor Crystal Shelley about sensitivity reading.

Listen to find out more about

Discover more about Crystal at Rabbit with a Red Pen. Mentioned in the show

Music Credit 'Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

0 Comments

In this episode of The Editing Podcast, Louise Harnby and Denise Cowle talk to thriller writer Andy Maslen about the creative-writing process.

Listen to find out more about

Here's where you can find out more about Andy Maslen's thrillers. Dig into these related resources

Music Credit ‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

In this episode of The Editing Podcast, Louise and Denise talk to Barry Award-nominated thriller writer John A. Connell about moving from Berkley (Penguin USA) to independent publishing.

Click to listen to Season 4, Episode 12

Listen to find out more about:

Top tips From John

Contact John A. Connell Subscribe to John's newsletter and get a free book:

Editing bites

Ask us a question The easiest way to ping us a question is via Facebook Messenger: Visit the podcast's Facebook page and click on the SEND MESSAGE button. Music credit ‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

In this episode of The Editing Podcast, Denise and Louise talk with linguist Rob Drummond about grammar pedantry, peevery, youth language, and non-standard language in context.

Listen here ...

Find out more about ...

Mentioned in the show

Music credit ‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Macros enable us to edit faster and more consistently. For professional editors, that means a higher hourly rate, a more consistent output, and a happier client. If you want to use macros but don’t know where to start, read on.

Which macros, and when and why?

Which macros should you use? How does the Paul Beverley macro suite fit with an application such as PerfectIt? What should you use when? No one’s the same. We edit different subject/genres, carry out different types of editing, and have different styles of working. There’s no one size fits all. A conceptual approach, however, can help us decide which tools to use. Analysis: Tasks versus goals A task-centred analysis focuses on what we plan to do and deciding what tools will help with these stages. Thus, in the free book, Macros for Editors, I offer smorgasbord of macros that speed up a variety of specific tasks. However, when we look broadly at what we’re trying to achieve, we may discover different ways of working and different tools – new tools, maybe – that can help. One such contribution to this approach is the Alyse suite – analysis-type macros (DocAlyse, HyphenAlyse, etc.) that provide an overview that reports on the likely inconsistencies in a document without our even having to look at the files.

Computer-aided editing: Teamwork

Think of computer-aided editing as teamwork – you and the computer working together, each playing to your own strengths, with a single aim: to improve communication between author and reader. A computer brings the following to the team:

On the downside, it lacks the ability to look beyond the data. It has no idea of meaning, significance, attitude, feelings – only humans can provide that. Mechanics versus meaning Editors spend a lot of time eliminating inconsistencies in the following:

This is the mechanical side of editing. Editors also spend a lot of time focusing on meaning. It matters little how consistent a document is if the meaning is clouded. Obscure the meaning, and communication between the author and reader is impeded. Using macros and related applications enables the editor to delegate some of the mechanical work to the computer – those mundane data-led tasks – and focus their minds on communication. A possible workflow Here’s one way it might look:

Here are the macros you might use in that workflow:

If you’re a PerfectIt user (see the Intelligent Editing website), you could use that instead at stages (3) and (5). Or continue to use FRedit for (3) but use PerfectIt for (5). The latter is a possible best-of-both-worlds approach if you like the idea of having two different tools, each working to spot errors that the other might have missed. False positives False positives are to be expected with any computer tool. We can reduce them by refining the FRedit changes list and PerfectIt’s style sheets. For best effect with global change macros, apply them to one chapter at a time, making adjustments that will make it more effective in succeeding chapters. Summing up To access all my line-level and analysis macros, download the free book. You can also watch almost 100 video tutorials on my YouTube channel. And if you want to know more about PerfectIt, visit the Intelligent Editing website. Please feel free to email me with suggestions and/or questions about macros.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Every writer has a process. What works for you might not work for someone else, and your approach might change over time. Here are 6 tips from indie author Kristina Adams that show how changing your writing process to suit mindset and circumstances can help you grow as a writer.

When I set out to publish my first book, I had no idea what I was doing. I made the whole thing up as I went along, absorbing as much advice as I could in the short space of time I had.

I’d set myself a tight deadline – to write, edit, and publish a book in a year – which, when you have no idea what you’re doing and you’re a one-woman band working a full-time job, is pretty insane. Fast-forward to now, and I’ve published four books and have a somewhat better idea of what I’m doing. I’m no expert, but I have come to accept that my writing process changes as I mature as a writer, as I grow as a person, and as my circumstances in life change. So let’s take a look at what's changed, and what you can learn from my ever-changing writing process ...

1. Planning is your friend

I never used to plan my writing. My dissertation tutor tried to convince me of the importance of planning, but I wouldn’t listen to him. (Pro tip: always listen to people more experienced than you, especially when you’re paying them.) When I started writing a book with multiple points of view and several spin-offs involved, his advice finally sunk in. Now, I don’t write anything without at least the hint of a plan first. Sometimes that plan is simply what the ending will be. Other times it’s so elaborate that there’s no room for missteps. It’s important to plan properly, though. A few years ago, I took part in NaNoWriMo. I was so excited that I’d planned my novel weeks in advance. When I went to write it in the October, I discovered – to my horror – that I hadn’t planned it very well at all. The Big Reveal scene was described as ‘Poppy finds out who the murderer is’. That was it. I’d spent all that time planning but hadn’t actually worked out the most important detail in a crime novel. Insert face palm here. The draft ended up being all over the place. I forced myself to hit the NaNoWriMo word count, but hated the piece so much that I almost quit writing fiction all together. (Another lesson learnt: don’t force yourself to finish a piece that you really, really don’t like any more. Not unless there’s someone else’s money on the line.) You don’t need to know every step along the way when you plan. I like to see it as akin to planning a journey: you know the destination and what stops you’ll make along the way, but you don’t know the other cars, the scenery, or the people you’ll come across. Planning is your friend, folks. It doesn’t dampen the creativity; it just stops you from digging yourself into a massive hole.

2. Listen to your body

This may seem like an odd thing to say in a post about writing, but as someone with six chronic health issues, I really do need to listen to my body. Too much stress exacerbates my fibromyalgia, which then means I’m too tired and in too much pain to function. It’s therefore imperative that when I start to feel weak, the pain gets too much, or the room starts spinning, I go to bed and close my eyes. Sometimes that rest is a couple of hours; other times it’s days. Either way, if I didn’t rest, I’d end up in a much worse state and wouldn’t be able to write or publish at all. So many people come to me and say, ‘I feel tired all the time’. If you fall into this category, I have three pieces of advice:

3. Abandon your book (just for a while)

It’s amazing how many things you can spot when you’ve taken a break from working on something. The longer you leave something in the drawer for, the more you’ll spot and the easier it is to work through any issues that you may or may not know about. I didn’t have much time to do this when working on What Happens in New York, but with more recent books I’ve written a first draft, then gone on to write another first draft of something else before going back to it. This means I’m working on first drafts while in a writing mindset; then I can switch to an editor’s mindset. Switching rapidly between writing and editing can be difficult, which is why I like to do them in bulk for longer projects. It strengthens my skills in both as I’m in that mindset for longer. It also means I’m less likely to overthink things during the crucial (but ugly) first-draft stage.

4. Ask for help

My local writing community has been pivotal to my growth as a writer. Whenever I get stuck on a particular issue, there’s always someone who can help. I have one friend in particular who’s brilliant at fixing plot holes, and so when I was unsure of something in my most recent book, she was the first person I went to. She helped me to figure everything out, and suddenly the book wasn’t so intimidating any more. I can’t emphasize enough the importance of a support network. Even if your support network doesn’t consist of other writers or editors (although it helps), having people in your corner that you go to for help when you need it makes a huge difference to your growth and your confidence as a writer. If you don’t have access to a physical writing community, there are plenty available online. Facebook, Twitter, and even Second Life have writing communities, and there are a plethora of websites that are dedicated to writing, too.

5. Be realistic with deadlines

When I set myself a 12-month deadline to publish What Happens in New York, I had no idea how much work was involved in self-publishing (unless one has a budget that far exceeds my monthly salary). Had I known, I would’ve set myself a different deadline. I ended up rushing a lot of processes early on and making rookie mistakes that make me cringe when I look back on them. Nowadays, I don’t put anything up for pre-order until the book is in a state that I’m happy with and only requires one last read-through to check for any niggling issues that might have been missed. Having a public deadline definitely helped to motivate me. Had I not had it, I may well have kept procrastinating, coming up with an abundance of excuses why I shouldn’t hit the ‘Submit for pre-order’ button. These days I don’t make my deadlines quite so public – I tell a few close friends that I know will hold me accountable instead. These are both fans of my writing and fans of me, which encourages me to keep going while also offering moral support when things go wrong.

6. Accept that you know nothing

The less you know, the more room you have to grow. The more room you have to grow, the more you can succeed. Everyone knows something that you don’t know, which is why it’s important to take advice from as many sources as you can. If someone has said something mean, acknowledge it, then ignore it. But if someone offers constructive criticism, take some time to think about their comments. It may be hurtful, but often the greatest pain comes from the greatest truths. No one likes their writing to be criticized, but it’s the only way you’ll improve as a writer. If those comments come from your target audience, it’s especially important to listen since they’re the ones that will download your book. If they don’t like something, they’re the ones you really need to pay attention to before you do something that could dampen your sales. As time goes on, you’ll learn the difference between constructive feedback and someone who's just got an axe to grind and you just happened to be their unfortunate target. In the end ... Everyone’s writing process is different. That’s part of what I find most fascinating about writing. I love hearing how different people write in different ways. I have some friends who plan their books in so much depth that they only need one or two edits. I have others who love editing but can’t stand first-draft stage. What really matters is that you find a writing process that works for you. Your writing process will change as you grow, and as your circumstances in life change. That’s natural. When you accept that, it becomes a lot easier to get your writing done. It also means you’re kinder to yourself, which means that you’re more relaxed. When you’re more relaxed, you can write better because you’re not putting too much pressure on yourself. Then, when you write better, you achieve more. And in the end, isn’t that what we all want?

Kristina Adams is an author, blogger, and reformed caffeine addict. She’s written four novels poking fun at celebrity culture, one nonfiction book on productivity for writers, and too many blog posts to count. She shares advice for writers over on her blog, The Writer’s Cookbook.

Are you looking for literary representation? My guest Rachel Rowlands has some helpful advice on how to find an agent, what to submit and to whom, and dealing with rejection professionally.

Literary agents hold the golden ticket that will get you into the chocolate factory. If you want to get published traditionally, they’re essential.

Getting an agent is competitive, and it isn’t easy, but if you’re stubbornly passionate about your work and don’t give up, it can be done. I hope my journey and what I’ve learned along the way will inspire you and help you. Buckle up, because it’s a bumpy ride.

Before submitting

The process starts long before you even think about submitting to agents. Write. Abandon projects. Start new projects. Finish projects. Learn about the craft. This can take years. You may even develop a few grey hairs along the way. I’ll rewind a bit and give you an example: I’ve always written stories. I wrote my first ‘novel’ when I was 16. It was about angels of light and darkness and doors to other planets, and it was heavily inspired by Kingdom Hearts, a game I was obsessed with. But I had fun, I loved writing it, and it taught me how to plan and finish something. I wrote three other books before writing the one that led to me signing with an agent – at 27. You need time to develop as a writer, to hone your craft. Your first book most likely won’t be the one that gets you where you need to be. Your second might not either, and that’s okay. No one becomes an expert overnight. Here are some other things that you might want to do before you start hunting for that elusive agent, aside from writing books until your fingers nearly fall off:

Finding and submitting to an agent

Do your research No agent should charge you money – they work on commission. Any agent who wants you to pay upfront is a scammer and you should run far, far away. A great place to hunt for agent details if you’re in the UK is the Writers’ & Artists’ Yearbook. QueryTracker is great, too; it lists agents from all over the world (although some UK-based agents are missing from the database). You can even use it to track your submissions and the replies you receive. Otherwise, I recommend doing your own tracking via, say, a spreadsheet. It doesn’t matter where in the world you’re based in terms of who you submit to – many agents work with foreign co-agents. So, for example, if you’re based in the UK it’s perfectly fine to query both UK and US agents. Follow submission guidelines Every agency has different guidelines – some want you to send a cover/query letter and three chapters. Others might just want an initial query letter. Treat these guidelines as law. Also, be professional in your letter (read Query Shark, a blog on writing query letters, like your life depends on it). Get someone to critique your query letter before it goes out. Don’t make it easy for someone to say no! Don’t send your book to everyone at once Submit to a small batch of agents first, somewhere between 5 and 10. If you get any feedback, rework your manuscript and then send out a new batch. Note, however, that this strategy can be problematic because you won’t always know why an agent rejects a book; it might be purely subjective. Still, you don’t want to exhaust all your options in one go! Try to keep it balanced. Don’t get keyboard-happy and send your book to 200 agents.

After submission

Be in it for the long haul and be prepared for rejection I submitted two manuscripts over the course of two years, racking up a couple of hundred rejections. It wasn’t easy. The first book I queried got standard, copy-and-paste rejections almost across the board (also known as ‘form rejections’), although two agents did ask to read it. One asked me to send it back after doing some revisions, sometimes called an R&R or a revise and resubmit (sadly it doesn’t mean rest and relaxation). I never heard from that agent again, even after several polite nudges. As for the second book I sent out, there was a flurry of interest. Suddenly, lots of people wanted to read my book. But then … the standard rejections started rolling in. I even had an agent ask to meet me when she was halfway through my book. Then she called and rejected me after she’d finished reading. A phone call from an agent is generally a sign that they want to work with you, so that was pretty crushing. Some days, I wanted to quit because it felt easier than carrying on. But in the wise words of J.K. Rowling, ‘It is impossible to live without failing at something, unless you live so cautiously you might as well not have lived at all.’ I kept going. Another agent called me up. We talked revisions. I worked on them for six weeks and we bounced ideas back and forth. She really got my book and what I was trying to do, and she loved my edits. After two and a half years of submitting, five manuscripts, and many I’m-going-to-quit-writing-forever threats, I signed the contract. Don’t reply to rejections Really, don't, unless the agent personalized your rejection and mentioned your book/characters specifically. In that case, feel free to send them a quick thank-you note. Never send sassy or scathing replies like, ‘You don’t know what you’re missing out on’ or ‘Your loss, sucker’, even if that’s what you’re thinking. Vent in private. That’s what writer friends/cats/brick walls are for. If an agent sends you a rejection, but invites you to submit future work, do it! They haven’t slammed the door shut, they’ve left a gap for you – and it means they see potential. Keep their name and email address, and when you have a new project ready, send it to them and remind them who you are. All in all, remember that no project is ever wasted. You’ll learn something from every manuscript, and even if you don’t land an agent straight away, you’ll be making connections and putting your name out there. Treat your rejections as badges of honour because they mean that you’re still in the game, and one day you’ll get to the next level. Good luck! More resources

Rachel Rowlands is an independent editor and an author of young adult books. With her editor hat on, she works for a growing list of publisher and author clients on both fiction and trade non-fiction. She has a degree in English and Creative Writing and is represented by Thérèse Coen at Hardman & Swainson. She can be found at www.racheljrowlands.com and on Twitter: @racheljrowlands.

Louise Harnby is a fiction line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in helping self-publishing writers prepare their novels for market.

She is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors, and runs online courses from within the Craft Your Editorial Fingerprint series. She is also an Advanced Professional Member of the Society for Editors and Proofreaders. Louise loves books, coffee and craft gin, though not always in that order. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. If you're an author, take a look at Louise’s Writing Library and access her latest self-publishing resources, all of which are free and available instantly.

Have proofreading symbols passed their use-by date? It’s a controversial question, but one that we definitely need to ponder. So, as an unconventional ‘celebration’ of 30 years in publishing, Melanie Thompson is setting out to answer this question – and she needs your help ...

Over to Melanie ...

A few months ago a colleague asked me whether (UK-based) clients want proofreaders to use British Standard proofreading symbols or whether they prefer mark-up using Acrobat tools on PDFs. ‘Good question,’ I replied. ‘I hope to be able to answer that later this year.’ That probably wasn’t the answer they were expecting. The widely different expectations of clients who ask for ‘proofreading’ has been niggling at the back of my mind for a couple of years. What's changed in three decades I have been a practising proofreader for 30 years, I’ve managed teams of editors and proofreaders, and I’ve been a tutor for newcomers to our industry. Yet I still learn something every time I proofread for a new client. It’s several years since I was last asked to use BS symbols for a ‘live’ project,* but I use them a lot on rough draft print-outs – because they’re so concise and … well, let’s face it, to some extent those symbols are like a secret language that only we ‘professionals’ know. I like to keep my hand in. But proofreading is now a global business activity, and ‘proofreading symbols’ differ around the world – which kind of defeats their original objective. And now so many of us work on Word files or PDFs (or slides, or banner ads, or websites or … ) and there are other ways of doing things. This all makes daily work for a freelance proofreader a bit more complicated (or interesting (if challenges float your boat). We might be working for a local business one day and an author in the opposite hemisphere the next. It’s rare, but not unheard of, to receive huge packets of page proofs through the mail and to have to rattle around in the desk drawer to find your long-lost favourite red pen. Usually, however, things tend to arrive by email or through an ftp site or a shared Dropbox folder. Digital workflows

The ‘digital workflow’ is something we’re now all part of, whether we realize it or not. But clients are at different stages in their adoption (or not) of the latest tools and techniques, and that leaves us proofreaders in an interesting position.

We need to be able to adapt our working practices to suit different clients; ideally, seamlessly. For that, we need to understand what the current processes are, and what clients are planning for the future. And that’s where I need your help. A new research project: proofreading2020 I’ve launched a research project, proofreading2020, to investigate proofreading now and where it might be heading.

The study begins with a survey, asking detailed questions about proofreading habits and preferences. Once the results are in, I’ll be conducting follow-up research for case studies and, early in 2019, publishing the results in book form.

You can find out more and complete the survey at proofreading2020. It's open now, and closes on 30 June 2018. Almost 200 proofreaders, project managers and publishers have already completed the survey. Several have contacted me to say it was really useful CPD, because it made them think about how they work and why they do things. So I hope you’ll be willing to set aside a tea-break to fill it in. It takes about 20 minutes to complete, but it’s easy to skip questions that aren’t relevant to you. There are only a handful of questions (at the beginning and end) that are compulsory (just the usual demographics and privacy permissions). Beyond that, the sections cover the following:

Your chance to join in!

Find out more and complete the survey at proofreading2020.

Don't forget, the closing date is 30 June 2018. * If a client does ask for BS symbols, I recommend downloading Louise’s free stamps for use on PDFs – they will save you a lot of time and help you deliver a neat and clear proof.

Melanie Thompson is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) and a CIEP tutor.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

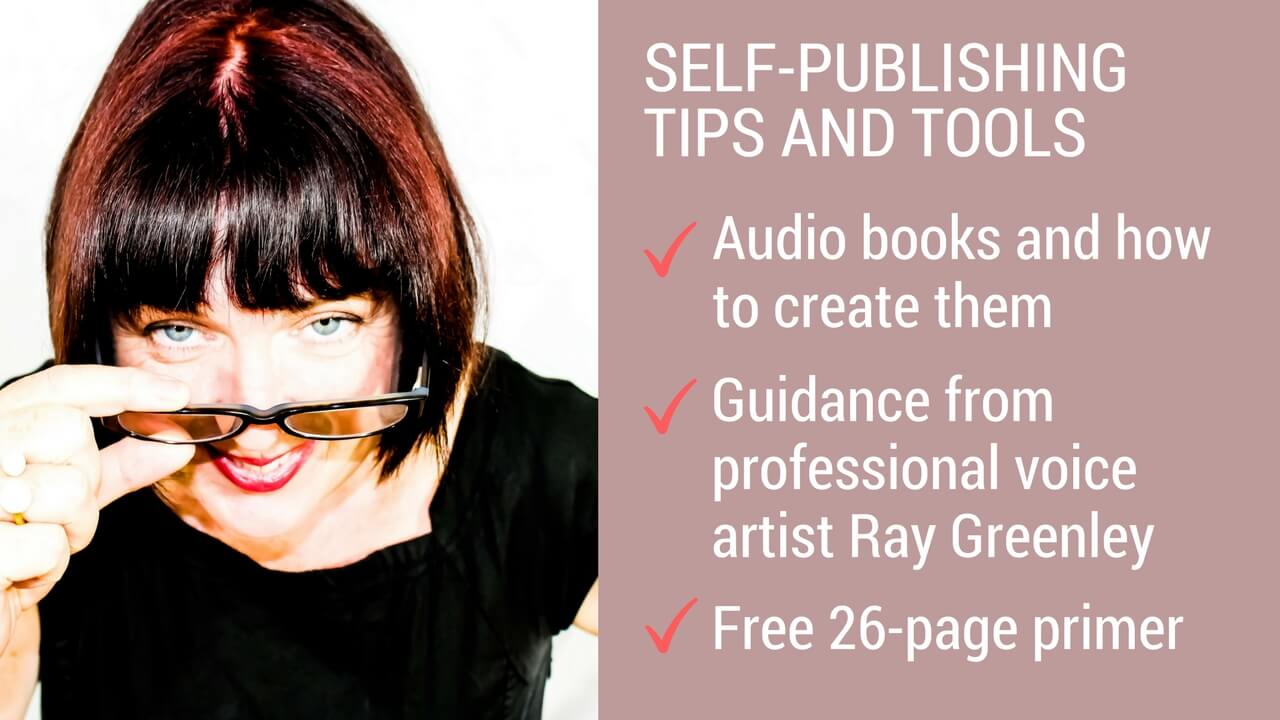

Here's the fourth part of my audio-book creation series. In this article, professional voice artist Ray Greenley discusses distribution options, the importance of having your manuscript edited prior to narration, and briefing your voice artist or producer. Here's Ray ...

Distribution decisions

So you’ve listened to your auditions, you’ve researched your potential producer and think they’re the one for your book, and you’ve come to an agreement on payment terms. There are a few other bits you’ll need to work out before you can offer the producer a contract. One is whether you want to distribute exclusively through Audible, Amazon, and iTunes for a higher share of the royalties from sales (royalties are 40% of sale price), or non-exclusively, which means you can set up distribution yourself through other platforms, but you’ll get a smaller share of royalties from sales through Audible, Amazon, and iTunes (royalties are 25% of sale price). Note that if you want to do a Royalty Share or Hybrid contract on ACX, you MUST do exclusive distribution. There’s some other information you’ll need to work out with the producer:

Different producers work at different paces; and many will have other books already waiting to be recorded. They might be able to start on your book right away and have it done in a week or two, or they might be scheduling out months in advance. Talk to your producer and let them know if you have any schedule in mind, but be ready to be flexible. Once you have those dates, you can offer the contract, and when it’s accepted you’re almost ready to go! There’s just one more thing you need to do, and that’s provide the producer with your final, ready-to-record manuscript.

Editing your manuscript

Now, I promise this isn’t just me sucking up to my gracious host, but please, for the love of all that’s good and holy, make sure your manuscript is edited and proofed by someone who knows what they’re doing. It makes the project many times more difficult when we have to struggle through bad grammar, missing punctuation, and poor formatting. In some cases (as happened with me early on), we can’t do it and the contract has to be canceled. If you find a producer who you like working with and does good work for you, then you’ll want to build that relationship into something ongoing. Handing them a manuscript that they can barely get through isn’t going to help. And while those grammar errors may seem innocuous enough on the page to your eyes, they’re VERY hard to hide in audio. Now, we producers know enough to not expect perfection. We can handle a reasonable number of errors in a manuscript. But in the end, it’s best for you, for us, and for your readers to get your manuscript properly edited, so please do it before sending the manuscript to us.

Briefing your producer

From here on out, it sort of depends on you and the producer. One thing that’s often very handy for a producer is to get some additional information about the characters in the story, including:

Also, if your book has words that your producer might have a hard time finding pronunciations for (particularly with made-up names in science fiction or fantasy books), having a key is really helpful. It’s really important to get this sort of information as early as possible while the producer is preparing to narrate the book, but before they’ve actually hit ‘record’. None of that stuff is vital; if you picked your producer well, they’ll be ready to handle all of that on their own. But having some guidance can definitely help. In the final article, we'll look at evaluating the first 15 minutes and production approval. Until then ... Resources

Contact Ray Greenley Website | Facebook | Twitter

Louise Harnby is a fiction copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in helping self-publishing writers prepare their novels for market.

She is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors, and runs online courses from within the Craft Your Editorial Fingerprint series. She is also an Advanced Professional Member of the Society for Editors and Proofreaders. Louise loves books, coffee and craft gin, though not always in that order. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. If you're an author, take a look at Louise’s Writing Library and access her latest self-publishing resources, all of which are free and available instantly.

If you think there's no place for macros in fiction editing, think again. My friend Paul Beverley has collated a core group of macros that will have any fiction line editor, copyeditor or proofreader drooling! Self-publishing authors will love them too!

I don't use all of these (every editor has their preferences) but some of them are staples and save me oodles of time!

Some of the macros apply when you’re looking at the whole text of a novel, while others are selective ... for use while you’re editing line by line. Bear in mind that they're designed to be used with MS Word files.

Macros that work with the whole text These macros are ideal near the beginning of the edit, when you’ve put together the whole book in one single file, and you want to look for inconsistencies. ProperNounAlyse searches the novel for any words that look like proper nouns; it counts their frequency, and then tries to locate, by using a variety of tests, and pairs of names that might possibly be alternative spellings or misspellings, e.g. Jayne/Jane, Beverley/Beverly, Neiman/Nieman, Grosman/Grosmann etc.

FullNameAlyse is similar to ProperNounAlyse, but it searches for multi-part names, Fred Smith, Burt Fry, etc.

ChronologyChecker is aimed at tracing the chronology of a novel. It extracts, into a separate file, all the paragraphs containing appropriate chronology-type words: Monday, Wednesday, Fri, Sat, April, June, 1958, 2017, etc. This file is then more easily searchable to look at the significance of the text for the chronology. WordsPhrasesInContext tracks the occurrence of specific names through a novel. You give it a list of names/words/phrases, and it searches for any paragraphs in the novel that contain them. It creates a separate file of those paragraphs, with the searched element highlighted in your choice of colour. CatchPhrase searches your novel for over-used phrases and counts how many times each phrase occurs.

Macros for when editing line by line

FullPoint/Comma/Semicolon/Colon/Dash/QuestionMark/ExclamationMark These macros change he said, you know ... into he said. You know ... or he said: you know ... or he said – you know ... and so on. FullPointInDialogue and CommaInDialogue These two macros change “Blah, blah.” He said. into “Blah, blah,” he said. and vice versa.

ProperToPronoun

This macro looks along the line to find the next proper noun, deletes it and types ‘she’. But if you then type Ctrl-Z, it changes it back to ‘he’. MultiSwitch You give this macro a list of changes that you might want to implement: Jane Jayne Beverley Beverly that which which that When you click in a word, and run the macro, it finds your alternate and replaces it. It also works with phrases and can also provide a menu of alternates: he said he opined he shouted he voiced she said she opined she shouted she voiced

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

An editor or book coach can teach you new ideas and techniques, and help you begin the journey of mastering novel craft right from the get-go ... if you're prepared to embrace a growth mindset. My guest this week is Lisa Poisso, a professional editor and writing coach who specializes in helping authors fix the big-picture problems.

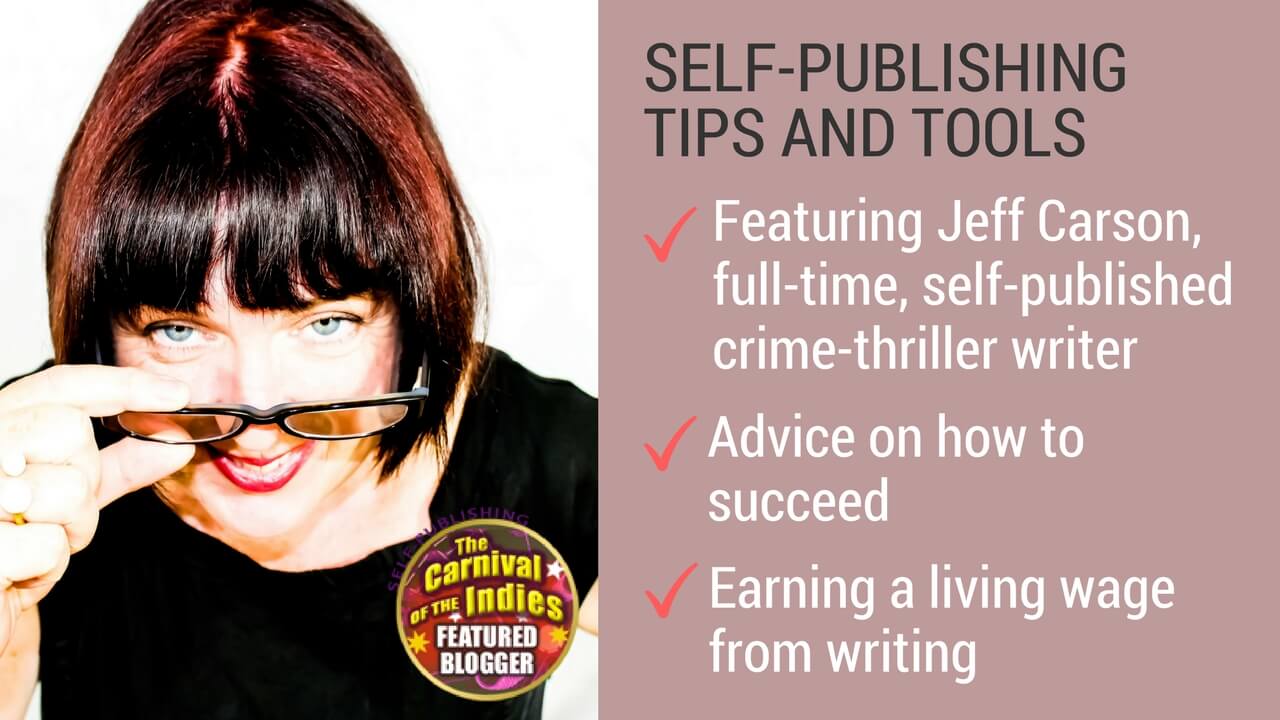

This post featured in Joel Friedlander's Carnival of the Indies #86

I don’t know what I’m doing, and I’m not very good. Will you fix my book? If this sounds like the way you tiptoed into your first professional edit, you’re due for a new mindset. An edit is a creative opportunity begging to burst open and drench you with new ideas and techniques.

There’s no better time to reach for growth than when you’re first starting out. You’ll hear a lot of publishing types claim that debut authors need to put in their dues. Write, they tell you, and fail. Write more, and fail again. That’s the apprenticeship process – or so they say. But it doesn’t have to be that way. Hiring an editor or writing coach can be a smart way to accelerate your learning curve. It’s all about the way you and your editor approach your edit. Are you feeding your writing with a fixed mindset or a growth mindset?

The growth mindset

If you’re a first-time author, your debut novel isn’t likely to hit it big. You know that. Editors know that. So you might tell yourself that there’s no sense in paying for a professional edit until readers start buying your books and ‘it really matters'. The problem is this: if your book isn’t very good and nobody wants to buy it, when will it really matter? Enter a new mindset about developing your craft. The fixed mindset, a term developed by Stanford University professor Carol Dweck, keeps your feet stuck to the same two dusty patches of dirt you’ve been standing on for years. With a fixed mindset, you accept that you possess finite abilities capped at a specific level. Editing is about propping up your shortcomings and repairing your inevitable mistakes. But editors can help you achieve so much more. Your editor can show you how to structure a compelling story, beef up the elements that drive your plot, solidify your language, and polish your writing voice. You’ll make strides it might have taken years to struggle through on your own. But that won’t happen unless you decide that developing your craft is worth the time, money, and effort. It won’t happen until you agree that you’re ready to grow.

Your first edit

A first novel is a learning experience. Authors call them ‘practice novels’ or ‘trunk novels'. They write their hearts out and then lock the results deep inside a file cabinet or trunk. The results aren’t all that different from the canvases artists create to experiment with and practise new techniques. They’re not meant for public consumption. Good on you for finishing your first manuscript. A complete novel is a tremendous achievement – but it’s unlikely that this first effort will become a bestseller. So start writing the next one. If you really want to make a go of this writing thing, you’ll need more than one good idea in a lifetime, right? Whip up the next concept and get it simmering. Meanwhile, seek feedback on the first manuscript from a writing partner or critique group. Give yourself the space to learn as you go rather than pinning all your hopes and ambitions on a single beginner’s effort. And then when you’ve finally written something your test readers and critique partners are giving you good feedback about, consider a professional edit.

The learning curve

You could keep plugging away for years, feeding book after book to your writer’s trunk. You might gain some confidence and make some incremental progress. But without professional feedback, you might not be able to figure out which parts of your story work and which don’t. You might not be able to spot what passages show a distinctive authorial voice and what parts are still mushy. At some point, it’s time for professional eyes. Send your manuscript to a few editors for a professional assessment. You’re not hiring anyone yet; you’re not paying for a critique or evaluation. All you want is that initial handshake. Every editor performs some sort of brief survey of new projects to help them decide if the project and type of work required falls within their wheelhouse. Ask the editor to flip through, take a peek at a few spots, and see if your work is ready for editing. What strengths and weaknesses do they spot? What kind of editing do they recommend? Would they take you on as a client or do they have other recommendations? If the results are encouraging, use the feedback you’ve gathered to help you choose a compatible editor. It’s time for some editing.

A learning experience

Even a routine, production-oriented edit is a learning experience. But when you hire an editor who enjoys working with authors bent on growth and improvement, an edit becomes something else altogether: an intense, one-on-one workshop in storytelling and writing. I like to compare your motivations for an edit to the motivations you create for the characters in your story. Your characters’ external, conscious motivations wrap around their secret, unconscious motivations – and the same goes for you. Polishing your manuscript for publication might be your conscious motivation, but with a growth mindset, you’ll come to realize that the real value of an edit lies in the substantial leaps you can make toward mastering your craft. Professional editing is no guarantee that your novel will be publishable in the end. But if you’ve chosen a qualified professional, you can count on acquiring invaluable insights into your writing technique. You can count on a growth experience.

What’s your writing worth to you?

I’m constantly astounded by the number of new writers who don’t believe that writing is worth the level of commitment any serious hobbyist would give their hobby. A recreational cyclist can easily drop thousands every year on bicycles, riding gear, event and travel fees, club and periodical subscriptions, and more. A collector of anything? The expenditures are obvious. But when it comes to writing, people somehow feel guilty about spending money on classes or craft books or editing to help them develop their passion. Just think how conflicted they must feel if they’re also harbouring hopes of getting published. Somehow, they have to go from beginner to professional with no help – and at no cost. Is a professional edit still worth it even if your book never gets any bites from an agent or sells more than 50 copies on Amazon? If using your manuscript to spring to a new level of skill ignites your creative jets, you’re ready to invest in yourself. You’re ready to turn a growth mindset into growth. It’s that simple. See you on the other side of the edit.

Lisa Poisso works with traditionally publishing and self-published authors to show them how to lift their stories to their full potential. She specializes in editing and coaching for commercial fiction, particularly upmarket and women’s fiction, action-adventure, and thrillers. She’s also a seasoned editor of fantasy, science fiction, and all flavors of speculative fiction.

Lisa has been a publication editor, journalist, managing editor, content writer, and communications consultant for more than 25 years. She holds degrees in journalism and fine arts and remains a working writer. She’s a member of the Editorial Freelancers Association and a charter member of the Association of Independent Publishing Professionals. Her studio staff includes her industrious editorial assistants – two greyhounds and a staghound. #45mphcouchpotatoes #adoptdontshop LisaPoisso.com | Twitter: @LisaPoisso | Facebook | Pinterest

Louise Harnby is a fiction copyeditor and proofreader. She curates The Proofreader's Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. If you're an author, you might like to visit Louise’s Writing Library to access her latest self-publishing resources, all of which are free and available instantly.

Macro Chat is back! This is where I hand over the Parlour reins to my friend, macro king Paul Beverley. A lot has happened since March: Paul's written lots more macros (close on 600 now) and has created another couple of dozen screencasts, 45 in all (see the Resources at the bottom of the blog for more on that). So over to Paul ...

What can macros do for you?

More and more people are taking a deep breath and loading their first macro tool. (I say ‘macro tool’ to differentiate my pre-programmed macros from those that you can record for yourself.) But why bother? What can macros do for you? 'I’m a proofreader – is there any point?' Most definitely! The better view you can get of the (in)consistency within your document before you start reading, the more problems you’ll be able to spot as you read through. Did the client pass on the editor’s style sheet? Maybe, but anyway, you can easily analyse your document to find the predominant conventions and get a count of the exceptions:

'I’m an editor, but do I need 600 macros?' Absolutely not! Indeed, that’s part of the problem, knowing where to start. (Sorry!) But if I suggest a possible general strategy, maybe that will help.

Fine! Except that (3) is a massive over-simplification. Let’s dig a bit deeper, and see how a macro-aided editor might work. FRedit – the powerhouse The principle I use (for books, anyway) is that I make as many changes as I can globally, but I do it chapter by chapter. I do a number of global find and replaces (F&Rs) on chapter 1, but I keep a list of them, so that I can do the same ones again on chapter 2 as well, and I don’t forget any of them. But hang on! Couldn’t you get the computer to go through that list and do all those F&Rs for you? Absolutely, and that’s what FRedit does! And it doesn’t just do the F&Rs, it allows you to add a font colour or a highlight to each and every F&R, and/or to track change (or not) each one – do you really want to track change all those two-space-to-one-space changes? But isn’t global F&R dangerous, especially when you can do a whole string of F&Rs at the touch of a button? Definitely, so start with just a few F&Rs and build up confidence; but if you colour or track all the changes, you’ll be able to see, when you read chapter 1, any inadvised F&Rs, so you can remove them or refine them. To give an example, if you changed every ‘etc’ into ‘etc.’ you’d get ‘ketc.hup’, ‘fetc.h’, etc.. (sic)! So use a wildcard F&R: Find: ‘<etc>([!.])’ Repl: ‘etc.\1’ (without those quotes, of course). And you don’t even need to work out those wildcard F&Rs yourself – just look in the library of F&Rs (provided free with FRedit) and gain from other people’s wildcard expertise. As you refine your F&R list, chapter by chapter, more of the dross is sorted out before you read, so (a) you miss fewer mistakes (as there are fewer to find, as you read) and (b) you can concentrate more on the meaning and flow of each sentence and (c) the job is more interesting, involving fewer boring tasks. Enjoy! Resources

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Here's more from my audio-book creation series. This time, professional voice artist Ray Greenley talks about doing it yourself, how long it will take and what kit you'll need. Over to Ray ...

In previous posts I talked about platforms (ACX), pricing, and sourcing and evaluating a professional voice artist for your audio book.

I know what you're thinking – 'There’s another option you’re not telling me about on purpose … I could avoid all these issues and just record my book myself!’ Yes, that’s true. You could. Okay … are you sure? I mean, REALLY sure? Because producing an audio book does take quite a bit of work. As a rule of thumb, a producer who knows what they’re doing will generally spend about six hours working to produce a single hour of finished audio. So if your audio book ends up being about 10 hours long, that means you could expect to spend about 60 hours working to produce it once you’ve invested the time in learning how, and the money in the equipment you’ll need. You'll need the following equipment (I'll go into more detail below):

There are some decent microphones that plug directly into your computer via USB, but generally you’ll get a better sound with an XLR microphone and a preamp.

Also, vitally, you’ll need a good space to record in. It should be quiet with plenty of sound-absorbing material in it to make the space sound as ‘dead’ as possible.

A walk-in closet can do the trick in a pinch, although chances are you’ll need some additional sound treatment to really get it acceptable. By the way, if you live in a busy area with a lot of traffic or other outside noises that you can hear from your space, then your space is no good unless you can somehow insulate against all those outside noises or are willing to record in the middle of the night when (hopefully) things are quiet. More on preamps and recording software Okay, well if you’re really on a budget, you can record using Audacity, which is free recording software. It has some solid tools and can do what you need. If you’re willing to invest some money, you can get some reasonably priced software that can do a bit more. I use Studio One Artist from Presonus, and I know some other narrators work well with Reaper. Both of those programs can be had for less than $100. There are many others as well.

For the preamp, there are some good options at a reasonable price. I currently use a Focusrite Scarlett 2i2, but I’m looking forward to upgrading to a Presonus Studio 2|6 soon.

Another reasonable option would be the Presonus AudioBox USB. One of the nice perks to getting one of the Presonus preamps is that it includes the recording software I mentioned earlier, Studio One Artist. Once again, there are lots of other options, many of which would probably be sufficient for your needs. The big question, the microphone So I can tell you that I use a Shure KSM32 and it works well for me. I’m pretty fortunate that I can sound good on such a relatively inexpensive microphone (US$499+).

Unfortunately, there’s absolutely no way to know if YOU will sound good on it, too.

Microphones really are very personal tools. One that works great for me might be terrible for you, and vice versa. Your best bet is to try several out and see what works well. The easiest way to do that is to find a specialty store that sells them; the store will often let you try some out before you buy because they’re aware of the difficulty in matching the microphone to the voice. ‘Okay, so once I’ve that all set up I’m good to go, right?’ So … no, not nearly. You still need to learn how to USE all that stuff, which takes a lot of time and effort.

I know this isn’t a surprise coming from me, but I think you’ll REALLY want to consider carefully when it comes to narrating your own book.

If you think you might really want to get into narration and put in the time and energy to learn how to do it right, then have at it. It’s very challenging work, but also very rewarding. There are very few people who have the right talents to be both a writer and a narrator, let alone have the time to train and use both sets of skills. My hat’s off to you! However, if you’re thinking you want to record your own book because you just want to try to save some money over paying a narrator to do it, or hoping to avoid the work of finding a good narrator who’ll take your book on as a Royalty Share project … please don’t. I promise it’ll take time you’d probably rather spend writing, and the chances of it really being a high-quality production are not great (no offence). In the long run, I’d bet it will cost you more than you’ll save, one way or another.

Next time we'll be looking at distribution, briefing the artist, and evaluating the first 15 minutes. Until then, thanks for reading!

Resources

Contact Ray Greenley Website | Facebook | Twitter

To read the 26-page primer in full now, visit the book's page: Audio-Book Production.

Louise Harnby is a fiction copyeditor and proofreader. She curates The Proofreader's Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. If you're an author, you might like to visit Louise’s Writing Library to access my latest self-publishing resources, all of which are free and available instantly.

My friend and colleague Denise Cowle is a specialist non-fiction editor who works with a wide range of businesses, so she understands the pressure to publish better than most. Here's her expert advice on when good enough is acceptable ... and when it's not.

Perfection and the pressure to publish

When you write for your business, is it perfect? Should it be? Small businesses without the benefit of a dedicated marketing department are increasingly recognizing the power that quality content has to raise their profile, connect with their potential clients and ultimately drive sales. However, the focus on publishing content regularly can pile on the pressure to get something – anything – out there, to keep up with the publishing schedule for your blog, or to update your web copy and marketing materials to reflect the latest developments in your field. Does this writing have to be perfect? Should we expect everything that people produce to be error-free? If you pay too much attention to the Grammar Police, you’ll be paralysed with fear that a misplaced apostrophe or misused word will bring your carefully constructed business crashing down around your ears. There’s no excuse for poor grammar, they’ll bellow, caps lock on, from behind the anonymity of their screens. Ignorance of correct spelling is the scourge of society, they’ll mutter, labelling you as feckless, careless and lazy, without knowing anything about you or your business, other than the fact you typed except instead of accept. But as an editor, and advocate of content marketing, I beg to differ. I think there are occasions when it’s OK to put out content with errors. Shock! I know! Am I doing myself out of a job here? Not exactly.

This is not permission to abandon all standards

Before you go rushing off to dispense with the services of your freelance editor and disable spellchecker, let me explain. I’m not for a minute suggesting that you should take this as permission to abandon all efforts to produce great, error-free copy. I’m working on the assumption here that you’ve taken time to make your copy the best it can possibly be within your time and budgetary constraints. I’m assuming you’ve used the tools and techniques available to you; you’ve run the inbuilt spellchecker or other software, read through your text carefully, and used a dictionary when you’ve been unsure. But sometimes, despite all your efforts, errors remain, either because you’ve missed them or because you don’t actually recognize them as errors in the first place. You go ahead and hit the publish button, and your mistakes are out there for all the world to see. We’ve all done it, but it’s rarely the end of the world. When is it OK to publish content with errors? In my view, it’s forgivable to have the odd mistake in content that:

It comes down to the purpose of the content, the medium you’re using, and the value your audience places on it. Your reputation will survive a typo in a tweet signposting your latest blog (I’ve done it myself and lived to tell the tale). Unless, of course, the typo is so unintentionally funny or rude that it goes viral! And even then, is there such a thing as bad publicity? It depends on your business, and what the error is. If you’ve created a free email course as lead generation I’d expect it to be error-free. However, the odd missing apostrophe or spelling mistake may not be a deal-breaker for your audience if the content is amazing and provides lots of value.

When is it not OK to publish content with errors?

It’s not OK to publish content with any errors if:

If you’re an editor or proofreader, to my mind this is a no-brainer. Your clients are looking for perfection, or as near as dammit. There is no margin for error here. And don’t think you can get away with proofreading your own writing because, let me say this clearly: You. Will. Miss. Things. Who wants to hire an editor with spelling or grammatical errors in their copy? The answer should be: no one.

Banish procrastination and publish!

No one wants to see any writing, however fabulous the content, strewn with spelling mistakes and grammatical blunders. But I’d much rather see you sharing your content with the world than keeping it in a draft folder because you’re worried that it might contain errors. Don’t allow fear to prevent you from publishing. Do your due diligence – run spellchecker, follow my tips on how to proofread your own writing – and get it out there! The world doesn’t stop turning because of a couple of typos, and you owe it to yourself and your business to write that copy, making it as good as you can. Should you hire someone to edit/proofread blog posts or other content? Rather than slogging over copy like it’s your overdue English homework, you might recognize that your time is better spent elsewhere and free yourself from the burden. If writing isn’t an enjoyable part of your work, wouldn’t it be better to outsource all or part of the process? Giving yourself permission to do this acknowledges that your time is a commodity in your business, and you have a responsibility to spend it wisely. You should consider this option when:

Is good enough, enough? Not everyone is blessed with the ability to write well and consistently, but I believe that everyone can improve with practice. Learning from mistakes is a crucial part of the process, and that can only happen when you write your web copy or publish your blog and allow other people to read it. Good enough can be enough when it’s on the road to even better.

Denise Cowle is a copy-editor and proofreader for non-fiction. She works with educational materials, reports, marketing copy and blogs. Her blog focuses on helping you to be a better non-fiction writer. Denise is an Advanced Professional Member of the Society for Editors and Proofreaders.

Further reading from Denise

Louise Harnby is a fiction copyeditor and proofreader. She curates The Proofreader's Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. If you're an author, you might like to visit Louise’s Writing Library to access my latest self-publishing resources, all of which are free and available instantly. Slipping into character – understanding the impact of narrative point of view (Sophie Playle)7/9/2017

Point of view can be difficult to master if you've not studied novel craft. My friend and colleague Sophie Playle has. She's an outstanding developmental editor who knows how to help writers get the big-picture stuff right. Today, she takes you through the fundamentals of narrative point of view so you (and your reader) know who's telling your story.

Over to Sophie ...

As an author, you have a lot of decisions to make when it comes to putting the ideas you have for your novel down on paper. Where should you start the story? Which characters should you focus on? Should you write in past or present tense? Third or first person? The possibilities are overwhelming.

It seems counterintuitive, but narrowing your options can be quite freeing. Once you’ve eliminated the paralysis of infinite choice, you can focus your creativity. Choosing the viewpoint from which you tell your story is one decision you should certainly consider. It doesn’t matter whether you think about this before you start writing or during the redrafting stage. Either way, by deliberately and purposefully aligning your narration with a particular character, you’ll be able to:

When a novelist hasn’t considered the point of view from which they’re telling their story, it makes things a lot harder for the reader. The story might lack focus, the characters might feel at arm’s length, and the writing style could fall flat. If you struggle with any of these issues, considering point of view could be the answer.

What is ‘point of view’ in fiction?

Let’s start with the basics. When we talk about point of view in fiction, we’re talking about the position from which the events of the novel are being observed or experienced. It’s essentially where you’ve decided to place the lens through which a reader accesses your story. [My writing] students talk about 'point of view' […] as if it were mechanical, when in fact it refers to the hardest and most thrilling thing we do—becoming someone else, becoming that person so thoroughly that if we’ve decided the person is nearsighted, we’ll imagine the room in a blur as soon as she takes off her glasses; if we’ve made him so jealous he can kill, we’ll feel mad rage down to our tingling fingertips when his girlfriend looks at another man.

Alice Mattison, The Kite and the String

But before we get into the details of slipping into character, we should back up a little. There are many narrative layers to a novel, and it’s useful to understand them.

Narrators, not authors, tell stories.** The difference is subtle, but important. If the author tells a story, the reader knows it’s made up. But if the narrator tells the story, it’s much easier for the reader to willingly suspend their disbelief and immerse themselves in what the narrator is saying. When you write, you – as the author – should disappear. Instead, you channel the narrator. The narrator can either be a character in the story or a disembodied observer. Either way, you see what they see, hear what they hear, and smell what they smell as they experience the events of your story. And depending on the type of narrator you’ve chosen to use, the narrator can also slip in and out of the perspective of your viewpoint character (or characters), experiencing the world through their body and mind, expressing those experiences using their language and style. I admit, it’s a little confusing to wrap your head around. So let’s take a quick look at the most common types of narration and the implications each can have on your writing, and hopefully all will become clear.

The different types of narration

FIRST PERSON First-person narration is when a character is telling the story from their own perspective and uses the pronoun ‘I’. Unless the character is telepathic, they will only be able to express the events of the novel from their own point of view and have knowledge of things only they have experienced. If they learn things from other characters, this knowledge will be filtered through (and potentially distorted by) their interpretation. Pros

Cons

EXAMPLE: If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you'll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don't feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth. In the first place, that stuff bores me, and in the second place, my parents would have about two hemorrhages apiece if I told anything pretty personal about them.

J. D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye

THIRD PERSON OBJECTIVE

Third-person narration refers to characters as ‘he/she/it’. Third person objective is used when the point of view from which the story is told is like a floating camera following the characters around. The narrator is almost invisible as it won’t express any thoughts and emotions and can only report on sensory experience – what could be seen, heard or smelt by any onlooker. There is no direct access to the thoughts and emotions of the characters, other than what can be interpreted by their dialogue and actions. This viewpoint isn’t normally used over the course of a whole novel, and it can be blended with third-person subjective (see below). Sometimes new writers will inadvertently use this viewpoint if they’ve taken the advice ‘show, don’t tell’ to an ill-considered extreme! Pros

Cons

EXAMPLE: Spade rose bowing and indicating with a thick-fingered hand the oaken armchair beside his desk. He was quite six feet tall. The steep rounded slope of his shoulders made his body seem almost conical—no broader than it was thick—and kept his freshly pressed grey coat from fitting very well. Miss Wonderly murmured, “Thank you,” softly as before and sat down on the edge of the chair’s wooden seat.

Dashiell Hammett, The Maltese Falcon

THIRD PERSON SUBJECTIVE (OR LIMITED)

Unlike with third person objective, the reader has access to the thoughts and emotions of the viewpoint character. The story is told only through one viewpoint character’s perspective at a time. We see, hear, smell, taste, feel and think what they do; the narrative is written in the character’s voice; and the reader can know only what the character knows. Third person subjective narration can be blended with third person objective narration to varying degrees. If the narrative is slightly more objective, the character’s direct thoughts might be made visually distinct from the main narrative by either being presented in italics or quote marks; if the narrative is very much subjective, separating direct thoughts isn’t necessary because the whole narrative is written from the direct perspective of the character. Jumping from one viewpoint character to another in close succession is known as head hopping and can be very confusing for the reader. It’s advisable to stick to one viewpoint character at a time. Pros

Cons

EXAMPLE: It was almost December, and Jonas was beginning to be frightened. No. Wrong word, Jonas thought. Frightened meant that deep, sickening feeling of something about to happen. Frightened was the way he had felt a year ago when an unidentified aircraft had overflown the community twice.

-- Lois Lowry, The Giver

OMNISCIENT

With omniscient narration, the narrator knows everything and isn’t limited to the viewpoint of any single character. An omniscient narration could be written in present or past tense, and use first or third person; they could be a character in the story (like a god or an enlightened person), or they could be an observing nonentity. Completely omniscient viewpoints are difficult to pull off well and have fallen out of fashion. Pros

Cons

EXAMPLE: Margaret, the eldest of the four, was sixteen, and very pretty, being plump and fair, with large eyes, plenty of soft brown hair, a sweet mouth, and white hands, of which she was rather vain. Fifteen-year-old Jo was very tall, thin, and brown, and reminded one of a colt ... Elizabeth – or Beth, as everyone called her – was a rosy, smooth-haired, bright-eyed girl of thirteen, with a shy manner, a timid voice, and a peaceful expression, which was seldom disturbed ...

— Louisa May Alcott, Little Women

Omniscient narration is quite complex, so let’s go into a little more detail. Omniscient narration can never truly be all-knowing because of the limitations of the nature of writing and reading: words must be read in order, so experiences must be felt in a linear way, which is not the same as having all knowledge in your head simultaneously.

Because of this, as with all writing, the issue is that of choice: what information does the omniscient narrator choose to divulge at any given time and, more importantly, why? Jumping from one viewpoint character to another (head hopping) should still be kept to a minimum to avoid confusion, and using an omniscient narrator is not an excuse for using this device in an uncontrolled way!

How to choose the right viewpoint for your novel

Choosing which type of narration to use will depend on the kind of effect you want to create, and the kind of knowledge-handling your plot requires. When deciding which point of view to choose, ask yourself the following:

These might not be simple questions to answer, but if you can figure out which answers are most important to you, you should be able to decide which narrative form and which character’s or characters’ viewpoints will allow you to tell the type of story you want to tell. How to control the POV in your story Once you’re aware of the issues of point of view, it’s surprisingly easy to control it and avoid confusion and inconsistency. All it takes is a little logical thinking, depending on your answers to the following questions:

Once you’ve answered these questions, it should be simple to use your chosen viewpoint in a consistent and focused way. How to handle multiple viewpoints Should you have multiple viewpoints in your novel? It’s really up to you – and will depend on the type of story you want to tell and the effects you want to create. The main advantage of sticking to one viewpoint is that it allows you to explore it in greater depth; the main advantage of using multiple viewpoints is that it allows you to explore the events of the novel in greater breadth. Switching the POV often makes it harder for the reader to really get to know a character. It’s the equivalent of going to a party and talking to a different person every twenty minutes. My advice is to keep your number of viewpoints to a minimum. Use only what the story needs – not what you feel like writing. If you have two narrators or characters telling the same story, you need a very good reason for it. When using multiple viewpoints, it’s imperative to make the switch between them seamless and clear. It’s best to start a new chapter or scene when switching viewpoints; at the very least, start a new paragraph. Whichever method you choose, keep the pattern consistent. Don’t just have one chapter in which there are multiple switches when all your other chapters stick exclusively to one viewpoint. Summing up The way you chose to narrate your story will have an impact on how your story is read. Different narrative styles allow you to create different effects. Choosing viewpoint characters brings focus, tension and originality to your writing. Controlling the point-of-view elements in your novel and learning to slip into character is one impactful way to become a better writer and write better books.

Further reading from Sophie

* One crucial thing you probably didn't realize about point of view ** Whose story is it anyway? How to choose your narrator

Sophie Playle runs Liminal Pages, where she offers editorial services to authors and training to fiction editors. Want a freebie with absolutely no strings attached? Sure thing. Click here to download ‘Self-Editing Your Novel’.

Louise Harnby is a fiction copyeditor and proofreader. She curates The Proofreader's Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. If you're an author, you might like to visit Louise’s Writing Library to access my latest self-publishing resources, all of which are free and available instantly.

Ever wondered how a professional book index is created? My colleague Vanessa Wells offers an honest and humorous glimpse into the world of a pro indexer – the challenges and the joys, and the 'sense of having created a beautiful thing'.

Let's take a peek in Vanessa's diary ...

I attended the Canadian national indexing conference in Montreal, where we – like most conference attendees – go to strengthen connections with colleagues and expand our professional knowledge. Since the indexing community in Canada is very small, this is a valuable investment and full of good people.

As a result of the conference, I’ve received a referral and am being hired by a university professor to write an index for a 220K-word anthology he’s editing with 22 chapters and almost as many contributors. It’s a ‘straightforward’ index of ‘names and titles’ which, of course, means that it’s both a name and subject index in reality. Yikes.

Against my usual policy, I agree to meet the professor in person, as the campus is close by and it would be faster than exchanging several emails. An excellent meeting results in ironing out expectations, discussing needs and agreeing we’re on the same page! It’s due July 26.

I send him my contract to review, and we discuss rates. Rate structure, I find from speaking to other indexers, is variable. Some people will work for $2/page; others charge much more. A figure I often hear is $5/page, but that definitely depends on your market – geographically and by genre, specialization, and timeline. An independent author writing a non-fiction trade book is not going to generate the same fee as a university-paid gig. Some indexers provide other means of calculating their fees, such as a flat project fee. I tell him my academic rate, and he agrees. I submit my invoice for a non-refundable 30% deposit, payable before work begins.

Proofs are due. They don’t arrive. They’re rescheduled by publisher for the 30th … While publishing timelines are often shifting (there’s a domino effect when a hitch arises), the end deadlines of proofreading and indexing are rarely budged.

So now I have to recalculate the number of hours and pages per day I’ll have to complete to meet the non-budging due date of July 26. Four days lost means Goodbye, weekends! for the duration.

It’s a long weekend here for #Canada150, our sesquicentenary. I’m so wiped from the previous month of conferences and making a second website for the new arm of my business that I take (most of) the weekend off. I can’t afford to get sick during this project. Self-care and all that.

Forgot I start a weekly course on Tuesday afternoons for the summer, with an appointment this morning. Will have to start tomorrow. Now that I’ve lost another 5 days, I’ll have not only to work weekends but very long days, everyday. My bad.

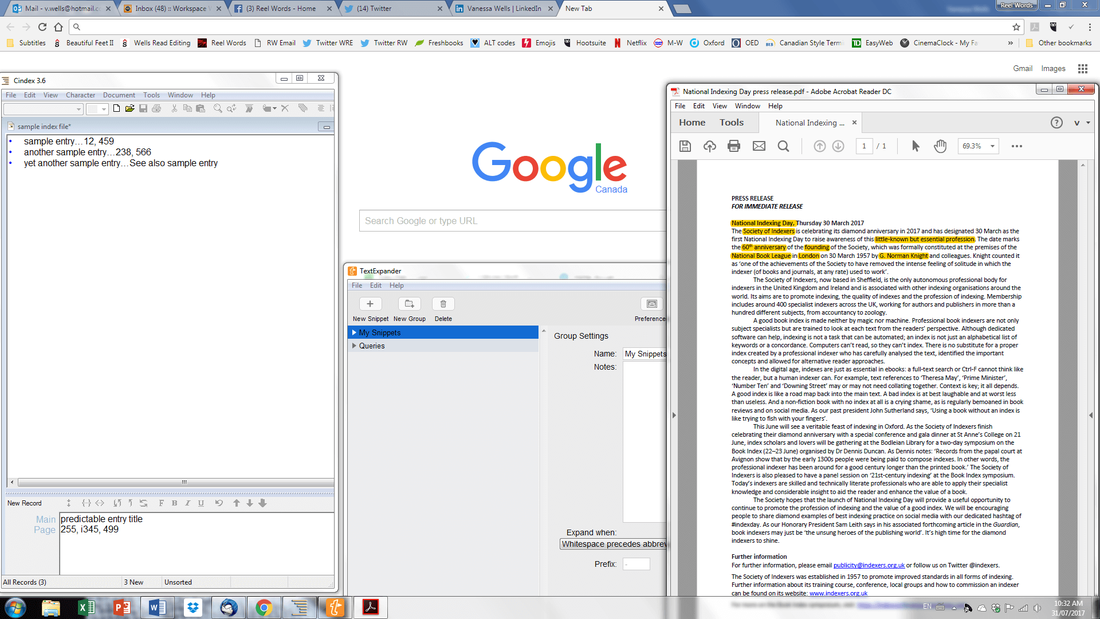

21 days to go: I begin the pre-read (see above photo) to start gathering my thoughts on how I’ll approach this behemoth. And I need at least 3 days at the end to edit the written index, so really I only have 18 days available.

I note there are A LOT of errors still in the MS. I judiciously email AU to double check that it’s been edited and that no other file is forthcoming. He confirms it has been copyedited … Sigh.

Re-install my $500USD indexing software on my new PC. Pay $39 for TextExpander, which is an online tool that lets you build a library of ‘snippets’, sort of like hot keys or macros, but it’s much simpler and faster. Using TextExpander for repeated, long index headings is making my life so much easier: it works pretty well with .ucdx files!

I’m already 50 pages behind. Indexing academic books is so much harder because you have to interpret the often-verbose language to get to the ideas (then re-edit them in your mind) and THEN start forming index relationships between the ideas on that and every other page.

Since there are almost two dozen authors in this anthology, I’m doing a lot of mental shifts. Why do I pine for indexes so much when they can be so draining?!? I’m being foiled by the very poor copyediting that was(n’t) done. I email the author-editor several times regarding his preferences for word options that I’m finding in the errata …

Working on a Saturday is particularly annoying when you hear other people having a great day off. Such is the freelance life.

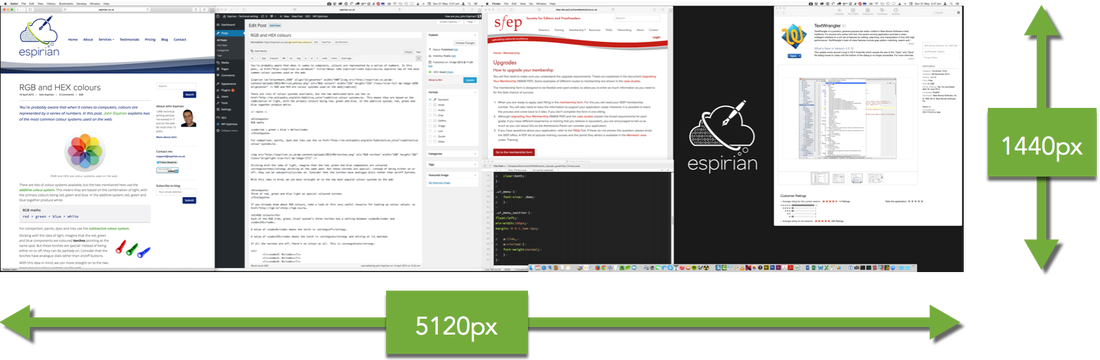

Here’s how I start an indexing day. Wish I had more than one monitor and can’t believe I used to do this on a 15-inch one!

CINDEX software file open; Google to check MS info, with related sites and academic books on the subject; book PDF marked up with terms needing indexing; and TextExpander to cut down on keyboard strokes. For the time being, I just type the entries into the index; refining connections comes later.

I emailed the author again about the serious issues around the practically non-existent copyediting of this book. It’s causing me to complete about 3pg/hr instead of 5–10pg/hr, never mind that I’m not being paid to correct such things, so again my budgeted time has to be rethought. He’d like errata forwarded to him so he can take the examples to the publisher and complain. (Understandably, he just doesn’t realize how much is involved in corrections before indexing can be done: research, confirm which instance is the error, note error, find other instances of it in MS, return to indexing the term and fixing all related cross-references). Ctl+F is my BFF. Wish I still drank alcohol. And for all you fellow CCLs, here’s what’s behind it all (because this, after all, is what’s important in life, not crying over indexes).

I had a good phone chat with the author about the terrible editing. (Again breaking the rules; normally I never share my number – learned the hard way with an abusive client once – but there’s too much to discuss via email.)

We’re hatching a plan to shame the publisher into redoing the copyediting or letting me do it. Either way, my schedule is messed up, and he’s sympathetic. What he’s told me about their process with him this far is appalling.