|

Words are the professional editor’s business, yet the ones we use in the course of discussing how we apply our craft are all too often prescriptive.

This post looks at problematic language, the messages it might unintentionally convey, and how we can talk about the editorial conundrums we come across without judgement.

|

|

Learn about how to use grammar and punctuation to amplify prose rather than butchering it with a rule book.

|

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

What's covered in this post

- How there are multiple Englishes with different spellings

- The difference between spelling style and voice

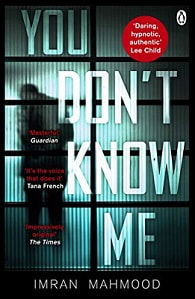

- A case study from the 007 files

- Overcoming ‘But it looks wrong’

- Adding regional flavour to voice

- 3 examples of when spelling inconsistency works

- A note on suffixes, dashes and quotation marks

Multiple Englishes, different spellings

Most words are spelled the same regardless of which English is in play, though there are many that aren’t, for example ‘color’/’colour’, ‘judgment’/‘judgement’, ‘harmonize’/‘harmonise’, ‘behavior’/‘behaviour’, ‘gray’/‘grey’, 'liter'/'litre'.

None are right or wrong, better or worse, or correct or incorrect. Rather, the way each version of English is spelled is about convention and style.

This post uses examples of American English (AmE) and British English (BrE) style to explain how to approach spelling/voice conundrums in fiction.

The difference between spelling style and voice

- How the words in a novel are spelled is for the most part a question of style.

- What a character says, thinks, feels, and the words used to report this on the page, is a question of voice. This is the case for dialogue and narrative.

Voice isn’t something that’s spelled. Rather, it’s something the reader experiences, ‘hears’ with their mind’s ear. It therefore follows the base spelling style, regardless of where the character comes from. With that in mind:

- If you’re writing fiction, decide on your spelling style and stick to it.

- If you’re editing for an author, identify the spelling style and aim for consistency.

The easiest way to illustrate how spelling consistency works is with a case study. Let’s take a peek into the world of 007!

A case study from the 007 files

The version from Hodder & Stoughton (part of Hachette UK), published in 2011, is styled as follows:

‘Now, I’m ninety per cent sure he’ll believe you,’ Bond said. ‘But if not, and he engages, remember that under no circumstances is he to be killed. I need him alive. Aim to wound in the arm he favours, near the elbow, not the shoulder.’ Despite what one saw in the movies, a shoulder wound was usually as fatal as one to the abdomen or chest.

The Night Action alert meant an immediate response was required, at whatever time it was received. The call to his chief of staff had blessedly cut the date short and soon he had been en route to Serbia, under a Level 2 project order, authorising him to identify the Irishman, plant trackers and other surveillance devices and follow him.

The version from Pocket Star Books (a division of Simon and Schuster), published in 2012, is styled as follows:

“Now, I’m ninety percent sure he’ll believe you, Bond said. “But if not, and he engages, remember that under no circumstances is he to be killed. I need him alive. Aim to wound in the arm he favors, near the elbow, not the shoulder.” Despite what one saw in the movies, a shoulder wound was usually as fatal as one to the abdomen or chest.

The Night Action alert meant an immediate response was required, at whatever time it was received. The call to his chief of staff had blessedly cut the date short and soon he had been en route to Serbia, under a Level 2 project order, authorizing him to identify the Irishman, plant trackers and other surveillance devices and follow him.

Later in the novel (Chapter 26), Felix Leiter, an American, joins Bond on his mission. Here’s how Leiter’s dialogue is rendered in the AmE version:

And here it is in the BrE version. Leiter is still American and still has the same distinct voice, but now the spelling has changed (as has the punctuation; note the spaced en dash and single quotation marks).

Overcoming ‘But it looks wrong’

For example, perhaps they use idiomatic phrases that wedge them firmly in a country, state/province/county or even town/city that we’re from.

The British editor working on a book set in Southern California and written by an American author who writes in AmE might well struggle when a viewpoint character from Norfolk (the UK one where I live) turns up in Santa Barbara and mutters the following on seeing a cluster of huge ladybirds:

“Look at the color o’ them bishy barnabees. And big as a thruppence too!”

The spelling of ‘color’ might jar because ‘thruppence’ is so clearly unAmerican, so very British, while ‘bishy barnabees’ is particular to Norfolk. And yet the spelling is (and should be) AmE if that’s how the novel’s been styled overall.

An editor colleague recently reported this kind of problem in a Facebook group discussion. The novel was set in AmE, but the British viewpoint character spoke, thought and talked to herself in a Yorkshire accent. The first-person narration style deepened the voice still further.

‘The character's voice is really strong,’ the editor said, ‘and the US spelling seems at odds.’

The editor slept on it and the next day announced a simple but clever solution that had enabled her to overcome her resistance.

‘I mentally changed the British voice to a South African one so that I'm not so conscious of spelling variations, et voilà! It's suddenly clear as day.’

It’s a neat trick, a way of breaking the false connection between spelling and voice. If you come up against a similar situation, try it!

Adding regional flavour to voice

It’s worth bearing in mind, too, that language is often borrowed to the extent that some words no longer feel like, say, Britishisms, Americanisms, Canadianisms or Indianisms when they roll out of our mouths, regardless of how we identify or where we live.

Would I, a Brit, ever use the terms ‘cell phone’ and ‘movie’ rather than ‘mobile’ and ‘film’? Yes, I would.

How about ‘elevator’ rather than ‘lift’, ‘sidewalk’ rather than ‘pavement’, ‘aluminum’ rather than ‘aluminium’? Would I refer to ‘my mom’ rather than ‘my mum?’ Not while roaming around Norwich, but on a visit to Chicago, possibly, if I wanted to ensure people understood me. And almost definitely if I'd made my home there for some time.

Perhaps, then, the trick is not to be too precious about it, either when we’re writing or editing. Instead, we can consider the character’s environment and the degree to which the ‘local’ language flavour is something they’re likely to have assimilated into their speech, thoughts and narratives.

Those choices aside, the spelling style will be consistent. Unless …

3 examples of when spelling inconsistency works

The character is spelling a spelling

Imagine a Bond novel is styled in BrE. Bond and Leiter are speaking to each other on the phone and the line is terrible. Bond thinks Leiter has said ‘dissenter’. Leiter’s dialogue might go like this: ‘Not dissenter. The centre. C-E-N-T-E-R. Move to the centre.’

A proper noun is being referenced

Now imagine Bond’s telling Leiter that he’s received intelligence about a heist in the Rockefeller Center. Even if the novel’s styled in BrE, the AmE spelling of ‘Center’ should be retained because it’s referencing the name of a building.

Excerpts from written materials have been transcribed

Excerpts from diaries, newspaper cuttings, reports, letters, texts and so on can be rendered in the spelling style most likely used by whomever in the novel wrote them because they’re supposed to be authentic transcripts.

Imagine that Bond’s reading a document written by an American CIA operative. Even if the novel is styled in BrE, the spelling in the report would be AmE, unless referencing a proper noun that required a BrE spelling.

A note on suffixes, dashes and quotation marks

Suffixes

In AmE, it’s standard to spell with -iz- suffixes.

In BrE, both -iz- and -is- are standard. Again, it’s a matter of style.

Thus, in the Night Action alert excerpt above, if Hodder had elected to use ‘authorized’ instead of ‘authorised’, this would not have been a slippage into American spelling but a style choice – an accepted BrE variant that’s been around since the sixteenth century.

Dashes

While most US publishers favour closed-up em dashes and most British publishers favour spaced en dashes when used parenthetically (see the Leiter snippet in the case study), it’s not wrong to used unspaced em dashes when writing in BrE style; it’s Oxford’s preference, for example.

Quotation marks

Again, while it’s more common to see single quotation marks in BrE styling and doubles in AmE, this isn’t an unbreakable rule. Indie authors can choose, for example, BrE spelling and double quotation marks if they wish.

In all three cases, consistency is what counts.

Summing up

Spelling is about style. The goal is consistency in the main, complemented by good-sense deviation when necessary.

That’s how the mainstream publishing industry approaches it, and editors and writers will do well to follow their lead.

Related resources

- Author and editor resources library

- Blog post: How do I find spelling inconsistencies when proofreading and editing?

- Blog post: How to convey accents in fiction writing: Beyond phonetic spelling

- Blog post: What's the difference between a rule and a preference? Advice for new writers

- Booklet: British English and US English in your fiction, and why you should be consistent

- Podcast: Think it’s American? Think again!

- Podcast: Linguist Rob Drummond on grammar pedantry, peevery and youth language

Visit the grammar and spelling page in my resource library to download a free booklet summarizing suffix variations in American and British English.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

FIND OUT MORE

> Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

> Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

> Learn: Books and courses

> Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Listen to find out more about

- What a zombie rule is

- Why split infinitives are not grammatically problematic

- Why it's okay to start a sentence with a conjunction

Dig into these related resources

- Blog post: Fiction grammar: Is it okay to start a sentence with ‘And’ or ‘But’?

- Blog post: What are expletives in the grammar of fiction?

- Blog post: Should I use a comma before coordinating conjunctions and independent clauses in fiction?

- Podcast: How to manage the grammar police

- Resources for proofreading your own writing

- Podcast: Linguist Rob Drummond on grammar pedantry, peevery and youth language

- Blog post: What's the difference between a rule and a preference? Advice for new writers

Music Credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Here's what two industry-recognized style guides have to say on the matter.

New Hart’s Rules (Oxford University Press): ‘You might have been taught that it’s not good English to start a sentence with a conjunction such as and or but. It’s not grammatically incorrect to do so, however, and many respected writers use conjunctions at the start of a sentence to create a dramatic or forceful effect.’

Chicago Manual of Style Online, 5.203 (Chicago University Press): ‘There is a widespread belief—one with no historical or grammatical foundation—that it is an error to begin a sentence with a conjunction such as and, but, or so. In fact, a substantial percentage (often as many as 10 percent) of the sentences in first-rate writing begin with conjunctions. It has been so for centuries, and even the most conservative grammarians have followed this practice.'

6 good reasons to start a sentence with ‘And’ or ‘But’

Great! We have the go-ahead from a couple of big hitters to use our two conjunctions at the beginning of a sentence. Now let’s dig a little deeper into why doing so can make fiction more effective. Here are my top six reasons:

- To serve natural speech

- To shorten narrative distance

- To introduce tension and suspense

- To add drama

- To emphasize the unexpected

- To make contrast explicit

Serving natural speech

When we speak in real life, conjunctions are often the first things out of our mouths. So it should be in novels that want to render speech authentically.

Fictional dialogue doesn’t replicate real-life speech completely – that would mean including a lot of boring stuff that one might hear at the bus stop. Rather, it’s a sort of hybrid that has the essence of reality but with the mundanity judiciously removed. It might sound like a cheat but readers thank authors who don’t bore them!

Small nudges towards reality help with the authenticity goal, which is where our conjunctions come in handy. Here are a few examples for you:

|

‘And you will have no hesitation in doing what has to be done? You have no doubts?’ (At Risk, Stella Rimington, p. 187)

‘And where’s he getting the money from? You know the situation as well as I do. He isn’t on leave of absence from a university.’ (The Dream Archipelago, Christopher Priest, p. 227) “But your way makes more sense. So you think Maura was working with Rex?” “I do.” “Doesn’t mean she didn’t set Rex up.” “Right.” “But if she wasn’t involved in the murder, where is she now?” (Don’t Let Go, Harlan Coben, p. 76) |

Shortening narrative distance

Dialogue gives us the character’s speech; narrative gives us the character’s experience. When that’s a first-person narrative, it’s easy to feel close to the narrator. With a third-person narration, the reader can feel separated from the character, as if they’re on the outside looking in.

Authors who want to reduce that space between the reader and the character – called narrative distance or psychic distance – can experiment with a narration style that sounds like natural speech even though it’s not dialogue.

Here’s a lovely example from Blake Crouch’s Recursion (p. 182).

|

There's a part of him that wants to run down there, charge through, and shoot every fucking person he sees inside that hotel, ending with the man who put him in the chair. Meghan’s brain broke because of him. She is dead because of him. Hotel Memory needs to end.

But that would most likely only get him killed. No, he'll call Gwen instead, propose an off-the-books, under-the-radar op with a handful of SWAT colleagues. If she insists, he'll take an affidavit to a judge. |

Notice how the narration style is third person, though it doesn’t feel like it. Instead, we’re right inside the viewpoint character’s head.

The position of the conjunction in this example isn’t the sole reason why the narrative distance feels short – the free indirect speech above and beneath plays a huge part – but it certainly helps to give us a sense of the character’s mentally working out a problem.

Introducing tension and suspense

Take a look at this excerpt from p. 21 of The Matlock Paper by Robert Ludlum.

|

Matlock walked to the small, rectangular window with the wire-enclosed glass. The police station was at the south end of the town of Carlyle, about a half a mile from the campus, the section of town considered industrialized. Still, there were trees along the streets. Carlyle was a very clean town, a neat town. The trees by the station house were pruned and shaped.

And Carlyle was also something else. |

With that one word – the conjunction – Ludlum stops us in our tracks. Yes, we’re thinking, the town’s neat, it’s clean. All well and good. But then we realize that there’s more to it, for beneath the pruned trees lies a dark underbelly.

The ‘And’, positioned right up front, forces us to pay attention to it. It’s not any old conjunction. Rather, it’s loaded with suspense that drives the reader to ask a question that isn’t explicitly answered: What else is that ‘something’?

Adding drama and modifying rhythm

In this excerpt from Parting Shot (p. 433), the author uses the conjunction at the beginning of the sentence to inject drama into a scene.

The new line makes the rhythm of the prose more staccato, but the ‘And’ at the beginning of the final line is what really packs a punch.

The viewpoint character, Cory, is a killer. He ponders almost matter-of-factly who the threats are, and reaches his conclusion as he closes in on the cabin.

|

Dolly Guntner certainly wasn't in a position to say anything bad about him.

Which left Carol Beakman. Carol had seen him. And while she didn't actually see him kill Dolly, if the police ever spoke with her, she'd be able to tell them it couldn't have been anyone else but him. As far as Cory could figure, the only living witness to his crimes was Carol Beakman. He was nearly back to the cabin. It seemed clear what he had to do. And he'd have to do it fast. |

If Linwood Barclay had omitted the conjunction, he’d have introduced a separation between two ideas: realizing what needs to be done, and when the killer is going to do it. Yet these two ideas are very much connected. The ‘And’ therefore fulfils its purpose as a conjunction – a joining word.

But there’s more. If he’d run the two ideas together with a conjunction between (‘It seemed clear what he had to do, and he'd have to do it fast.’), the line would have lost its wallop. The staccato rhythm (one that mirrors the cold calculation taking place in Cory’s head) is gone. Instead, the prose has flatlined; it seems almost mundane, like a stroll in the park rather than the planning of a murder.

However, the ‘And’ reinforces this extra information – the deed must be done fast. The emphasis adds drama to the line. The final line is still connected to the clause it’s related to, but the mood-rich rhythm, and the drama that comes with it, is intact.

Emphasizing the unexpected

An up-front ‘But’ is perfect for the author who want to emphasize the unexpected, surprise or absurdity. Take a look at this excerpt from Terry Pratchett’s Dodger (p. 170).

It’s true that omitting the ‘But’ would leave the meaning intact. However, adding the conjunction reinforces the Dodger’s emotional response to the boy’s suggestion – he’s taken by surprise because in times past, asking a peeler was exactly what he’d have done, without question, without fear.

And so that ‘But’ does more than act as a conjunction. With just three letters, we’re shown character mood.

Making contrast explicit and suspenseful

David Rosenfelt’s New Tricks (p. 92) includes a smashing example how the conjunction at the beginning of the sentence reinforces a contrast with what’s gone before.

|

I won't be able to place this in any kind of context until I go through everything Sam has brought, though he says he didn't see a reply to Jacoby's questions. Certainly the fact that a man who was soon to be a murder victim experimenting in any way with his own DNA is at least curious, and something for me to look into carefully if I stay on the case.

But a nurse comes in and asks me to quickly come to Laurie's room, so right now everything else is going to have to wait. |

That contrast is explicit because the ‘But’ acts as an interrupter. We’re deep in the POV character’s head regarding the murder victim, ruminating with our protagonist. The conjunction then shoves us out of that rumination. It’s not gentle; the ‘But’ is a big one – something’s up with Laurie.

Not that we know what. Rosenfelt doesn’t tell us yet. Instead, he makes us ask the question: Why? And with that question, just as with the Ludlum example above, we have suspense.

Summing up

Feel free to pepper your prose with sentences that begin with ‘And’ and ‘But’. Anyone who tells you you’re on shaky ground grammatically knows less about grammar than you do!

It’s likely that the myth around positioning these conjunctions came about in a bid to nudge people away from stringing together clauses and sentences with no thought to creativity. And while such an intention makes sense, we have to recognize that imposing this zombie rule on writing can actually destroy the magic of prose.

And on that note, I will sign off! (See what I did there?)

More fiction editing guidance

- 3 reasons to use free indirect speech

- Author resources library: Booklets, videos, podcasts and articles for authors

- Commas, conjunctions and rhythm

- Coordinating conjunctions

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level: My flagship line-editing book

- How to write suspenseful chapter endings

- Rules versus preferences

- Sentence length, pace and tension

- Switching to Fiction: Course for new fiction editors

- Transform Your Fiction guides: My fiction editing series for editors and authors

Cited sources

- At Risk, Stella Rimington, Arrow Books, 2004

- Don’t Let Go, Harlan Coben, Arrow Books, 2017

- Dodger, Terry Pratchett, Corgi, 2012

- Recursion, Blake Crouch, Pan Macmillan, 2019

- The Matlock Paper, Robert Ludlum, Orion, 2010

- The Dream Archipelago, Christopher Priest, Gollancz, 2009

- Parting Shot, Linwood Barclay, Orion, 2017

- New Tricks, David Rosenfelt, Grand Central Publishing, 2009

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Common examples are:

- there are/is/was/were

- it is/was

Take a look at the following pair. The first sentence is introduced by an expletive.

- There was a car parked outside the house.

- A car was parked outside the house.

When used well, expletives are enrichment tools that allow an author to play with a narrative voice’s register and the rhythm of sentences.

When prose is overloaded with them, it can feel cluttered with filler words that add nothing but ink on the page. At best, they widen the narrative distance between the reader and the POV character; at worst, they flatten a sentence and destroy suspense and tension.

Too much telling of what there is or was can rip the immediacy from a scene and encourage skimming. That’s a problem – it means the reader isn’t engaged and risks missing something.

Furthermore, if they’re not performing their rhythmic or emphasis role, expletives make sentence navigation more difficult because all they're doing is cluttering the prose.

Here's an example. Think I've overworked it? There are published books from mainstream presses with passages just like this made-up one.

It was a tiny room. There was a light switch with rust-coloured smudged fingermarks on the melamine surface. Was that blood? There was a noise coming from beyond on the back wall. It was a high-pitched whimper. Then there was silence. She held her breath and tiptoed forward.

Suddenly there was a scream.

The problem with the expletives in the passage above is that readers are bogged down in what there was rather than the viewpoint character's experience of discovery. Let's revise it to fix the problem.

The room was tiny. Rust-coloured fingermarks smudged the melamine surface of the light switch. Blood maybe. A noise came from beyond a door on the back wall. A high-pitched whimper. Then nothing. She held her breath and tiptoed forward.

A scream shattered the silence.

Notice how the narrative distance has been reduced in the revised passage. Now it's as if we're in the viewpoint character's head, moving with her second by second. We can focus on the room, the dried-blood fingermarks, the whimper, and the scream rather than the being of those things – their was-ness.

Removing the expletives and swapping in stronger verbs (smudged, shattered) enables us to tighten up the prose and introduce immediacy. And now there's no need for the told 'suddenly' – we experience the suddenness through the in-the-moment shattering.

As is always the case, obliterating expletives from a novel would be inappropriate because sometimes they're the perfect tool to help out with rhythm and emphasis.

The opening paragraph of Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities (p. 1) uses expletives galore, and masterfully at that. The repetition (anaphora) brings a steady rhythm to the passage that ensures the reader gives equal weight to the contrasting extremes – from best and worst to hope and despair.

The expletives introduce a detached sense of reportage that forces us forward rather than allowing us to dwell on any of the heavens or hells on offer. It’s simultaneously mundane and monstrous, and that's why it's magical.

And here’s an example from Dog Tags (p. 1) where omission of the expletive would rip the energy from the opening first line of the chapter and interfere with our understanding of which words we’re supposed to emphasize.

That was the USA Today headline on a piece that ran about me a couple of months ago.

Summing up

Grammatical expletives are a normal part of language and have every right to be in a novel. Overloading can destroy tension and make for a laboured narrative, but a purposeful peppering can amplify character emotion, moderate rhythm, and make space for the introduction of big themes in small spaces without sensory clutter.

Cited works and further reading

- Author resource library (includes links to free webinars)

- A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens, W. W. Norton & Company; Critical edition, 2020

- Dog Tags, David Rosenfelt, Grand Central Publishing, Reprint edition, 2011

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level: A Guide for Beginner and Developing Writers

- Making Sense of Punctuation: Transform Your Fiction 2

- ‘Playing with sentence length in crime fiction. Is it time to trim the fat?’

- ‘Playing with the rhythm of fiction: commas and conjunctions’

- 'Should I use a comma before coordinating conjunctions and independent clauses in fiction?'

- ‘What is anaphora and how can you use it in fiction writing?’

- 'Why "suddenly" can spoil your crime fiction'

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Some writers and editors love a rule. I’m not so keen on the language of ‘rules’ because it sets up a binary mindset that’s focused on ‘wrong’ versus ‘right’ rather than clarity of meaning. Instead, I prefer to think in terms of convention.

Grammatical conventions are useful and purposeful. They provide us with a common frame of reference that helps us communicate clearly through the written word. We can start by at least acknowledging the following:

- Breaking with convention requires understanding convention’s intent.

- However, ignoring convention doesn’t always render a sentence unreadable or misunderstood.

- And adhering to convention doesn’t always mean a sentence is as powerful as it could be.

Balancing convention and meaning

Writing and editing fiction requires deciding when to break with convention. But how do we work out what works and what doesn’t? Here’s how I frame the balancing act:

- Punctuation should serve meaning as long as that doesn’t butcher rhythm.

- Rhythm should serve emotion as long as that doesn’t butcher understanding.

- Both should serve the reader and the story rather than the style manual and the grammar book.

So how does that apply to commas, coordinating conjunctions and independent clauses?

What are coordinating conjunctions?

Coordinating conjunctions are words that join other words or groups of words of equal weight. You might see them referred to in short as FANBOYS:

|

Independent clauses are groups of words that can stand as a sentence on their own and still make sense. They include a subject and a predicate.

Subjects are people/things that are doing something or being something – the noun (the thing) and the adjectival information describing that noun. The four examples given below are all subjects.

- Louise

- That fiction editor Louise Harnby

- The dog

- The Labrador in the corner

Predicates are what they’re doing – the verb (the doing word) and the thing the verb’s acting on. The four examples below are all predicates.

- slumped over the desk.

- loves working on thrillers.

- licked its paws.

- is pale yellow.

Joining subjects and predicates gives us independent clauses. Here are two simple examples (subject in bold; predicate underlined).

- The dog is pale yellow.

- It is licking its paws.

If two or more independent clauses in a sentence are joined by a coordinating conjunction, it’s conventional to place a comma before that conjunction.

EXAMPLE AND EVALUATION #1

In the following example, the independent clauses are in bold.

The independent clauses could stand on their own as complete sentences and be understood perfectly well. Let’s revisit our balancing act and assess the impact of the comma.

The degree to which the comma serves meaning here is, I think, debatable. This is what it looks like without the comma:

There’s no ambiguity there, and so one could argue that insisting on a comma would be grammatical pedantry. An editor would struggle to justify adding a comma for any other reason than ‘that’s the rule’ or 'I think it looks better' because the meaning is perfectly clear.

Could someone argue that the comma enforces the equal weighting of the independent clauses lying either side of the coordinating conjunction?

Yes in that it acts as a separator of two ideas: the dog’s colour and what it’s doing to its paws; the one isn't related to the other. And so I certainly wouldn’t remove it if it were already in place; there’s no justification for such an action.

MORE COMPLEX CONSTRUCTIONS

Many sentences in fiction are more complex. If our example looked like this, we might have a sounder justification for adding the comma:

In the revised example below, I think applying the conventional punctuation helps. The rhythm is moderated – we take a little breath when we reach the comma – and experience (through our viewpoint character’s eyes) first the colour of the dog and then what it’s doing and why.

The two ideas have a starker separation, and the punctuation convention supports that meaning.

EXAMPLE AND EVALUATION #2

Here’s an excerpt from Robert Ludlum’s The Janson Directive (Orion, 2003, p. 355). Once more, both independent clauses are in bold.

The independent clauses could stand on their own as complete sentences and be understood perfectly well. Again, let’s revisit our balancing act and assess the impact of the comma.

I think the comma serves meaning and is necessary. Without it, we might start to read the sentence as if the slug would shatter not just a skull but another life too. That’s not what Ludlum is saying. Instead, we’re alerted that another idea is coming into play.

A trip-up here means the reader would have to fix the grammar in their head and reread the sentence to make sense of it. That’s a momentary distraction no writer wants.

Let’s have a look at when we might ignore grammatical convention.

Below is a short scene I’ve made up. Our protagonist is a forty-year-old woman having a nightmare about a past event.

I wake, slick with sweat, the six-year-old me hovering spectre-like in my mind’s eye. It’s the third time I’ve had that dream in the past week.

There are three independent clauses (and the start of a fourth) linked by a coordinating conjunction. The ‘rule’ says there should be a comma before all those ‘and’s.

EVALUATION

A pro fiction editor would want to think twice before they start adding in commas because of some rule or other.

- First of all, we need to recognize the literary device in play here – anaphora: deliberate repetition for the purpose of emphasis or meaning – in this case ‘and it’s’.

- Notice, too, how the beats in those independent clauses are similar: dee-dum-da-dum, dee-dumdum-da-dum, dee-dumdum-dada-dum.

Using anaphora doesn’t mean we have to ignore commas, far from it. But what would introducing them do to rhythm and mood?

I think the lack of commas helps us to feel our way under the skin of that dream-child because young children in a panic don’t introduce pauses or moderate their speech according to a style manual or a grammar guide. Instead, words fly from their mouths like tiny storms.

What we have instead is the sense of terrified disorientation being experienced by the dreamer, one that’s shown rather than told.

Commas would moderate the pace and separate the ideas contained in each independent clause; omitting them means we’re offered a stream of terrified consciousness.

Some grammarians do allow for an exception when the independent clauses are short and closely related.

In the examples that follow, the coordinating conjunctions are underlined; notice the absence of the preceding comma. Sense isn’t marred because of the missing punctuation.

- The gig was finished but no one seemed keen to leave.

- ‘You need to return that or the boss is going to fire you,’ said Harvey.

- She’d told him three times yet he wouldn’t listen.

- The dog is almost white so it stands out in the dark.

- Mara was late yet again and Aisha was furious.

It’s an eminently sensible exception – one that allows for decluttering but also avoids a separation of ideas that isn’t appropriate.

- In the first example, ‘no one seemed keen to leave’ is an independent clause, but the reason for telling us this rests on the gig being finished. No comma required.

- In the fifth example, Aisha’s fury is standalone, too, but it’s a result of Mara’s tardiness. No comma required.

Summing up

The grammatical convention of placing a comma before a coordinating conjunction linking independent clauses is helpful and useful. However, sometimes we can omit those commas:

- Because the comma interrupts rhythm and emotion, and therefore shown meaning.

- Because the meaning is clear, and a comma would be unnecessarily cluttering.

- Because the comma introduces an inappropriate separation of ideas.

Style and grammar resources offer guidance, and we should use them, but only in so far as they serve the reader and the story, not because we are rule enforcers. That’s nothing more than a road to literary butchery.

More resources to help you line edit with confidence

- Author resource library (includes links to free webinars)

- Editing Fiction at Sentence Level: A Guide for Beginner and Developing Writers

- Making Sense of Punctuation: Transform Your Fiction 2

- ‘Playing with sentence length in crime fiction. Is it time to trim the fat?’

- ‘Playing with the rhythm of fiction: commas and conjunctions’

- ‘What is anaphora and how can you use it in fiction writing?’

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Reflexive pronouns can act as double tells by stating the obvious, and mar pace and tension.

Stating the obvious

- Max grabbed a fistful of dandelion leaves and shoved them into his mouth. Needs garlic, he thought to himself.

- Jenny wondered to herself about the dream – it had been so real, as if she’d had full control. And yet …

When it comes to internal musings, authors can ditch the reflexive pronouns. Thoughts take place inside a person’s head and, by definition, are offered only for the thinker – unless there’s telepathy going on in the novel!

Moderating pace and reducing tension

- Max ducked, rolled himself over the floor and grabbed the Browning. Fired out two shots. Both hit home.

- Ali sprinted down the street and swung herself into the shadows.

These are high-tension scenes. Max is in a shoot-out; Ali’s escaping danger. Every word stretches out the sentence. And as the sentence length loosens, so does the tension.

Look what happens when we remove the pronouns:

- Max ducked, rolled over the floor and grabbed the Browning. Fired out two shots. Both hit home.

- Ali sprinted down the street and swung into the shadows.

The sentences shorten, the pace increases – and so does the tension.

We shouldn’t omit all -self pronouns. There are occasions when a sentence works better with them. Sometimes they’re essential.

Clarity

In some cases, the pronoun is necessary for clarity. The reader can’t be sure of what the verb’s object is without it. In the examples below, removing the pronouns could leave the reader with questions: Ashamed of what? A promise to whom? Stop what? Consider whom an expert?

- Ordinarily, she’d have been ashamed of herself, but there was no guilt – not this time.

- I made a promise to myself never again to lose my rag over something so inconsequential.

- He couldn’t stop himself; it took five minutes to demolish the chocolate egg.

- I consider myself an expert, and no one will convince me otherwise.

Emphasis

The pronoun can be used to emphasize the person being discussed. Omission would leave the sentence grammatically intact but change the mood and pacing. In this case, it’s a judgement call on the author’s part.

- Sarah told me so herself.

- The queen herself told me.

- John hadn’t been the only one having a hard time. I myself had been suffering from anxiety at the time.

Sense

Some sentences don’t make grammatical sense without a reflexive pronoun. Remove them and the writing leaves more than questions: it’s unreadable.

- She had to defend herself from that monster – no two ways about it.

- Cass doused themself in perfume.

- Why shouldn’t he call himself the King of Hearts? Who cares if it sounds daft? Daft is good.

- He dragged himself to the top of the stairs.

At the top of this post, I offered examples of how -self pronouns can reduce tension. There will be occasions when an author wants to do exactly that.

- I was trying to make a new life for myself. That’s all there was to it.

- I was trying to make a new life. That’s all there was to it.

There’s a more staccato feel to the second version above that might jar if the author’s seeking a contemplative mood.

Still, too much self-ing can make even a stress-free scene overly wordy so it’s always worth thinking about whether a leaner version would be more immersive and get the reader from A to B faster.

In the first version of the triplets that follow, the pronouns introduce a chilled-out sense of laissez-faire to the movement. In the second I’ve omitted them. And in the third, I’ve ditched the mundane movement and focused on the essential beat.

- He found himself a chair and sat down.

- He found a chair and sat down.

- He sat down.

- Maxie busied themself with the coffee machine and settled down to read the letter.

- Maxie made a coffee and settled down to read the letter.

- Maxie read the letter.

- She got herself up and called Mel.

- She got up and called Mel.

- She called Mel.

It’s always worth an author spending a little time on thinking about how much micromanagement of a scene is necessary.

Will the reader care about the chair discovery, or that Maxie had a hot drink while they were reading the letter, or that the protagonist was no longer on the sofa when she called Mel?

Perhaps. If that stuff’s central to driving the novel forward, to reflecting mood, to grounding the character in the environment, the pronoun and the stage direction might be necessary. If it’s clutter that can be removed without damaging reader engagement, lean up the scene!

Summing up

Use reflexive pronouns when they’re necessary for clarity, sense and emphasis. Otherwise, consider leaner prose that focuses on what the reader needs to know to move forward in the story.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Listen to find out more about:

- Who are the grammar police?

- Social media and the grammar police

- Pedantry versus professional editing for style, preference and flow

- Writing style: Business, academia, web copy, creative non-fiction, fiction

- Conventions and standards versus rules and errors

- How and when to tell a writer about an error

- Dealing with the grammar police

Editing bites

- Blue Book of Grammar and Punctuation, by Jane Straus

- TextExpander

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

What is a comma splice?

When two independent clauses – which could stand on their own as sentences and make perfect sense – are separated by a comma, the sentence is said to contain a comma splice. For example:

- I love tomatoes.

- Red and yellow ones are my favourites.

Those two sentence above could be separated by a semi-colon, a dash, or a full stop and no one would be breathing grammar rules down your neck:

Standard punctuation

- I love tomatoes; red and yellow ones are my favourites.

- I love tomatoes – red and yellow ones are my favourites.

- I love tomatoes—red and yellow ones are my favourites.

- I love tomatoes. Red and yellow ones are my favourites.

However, if you use a comma to separate them, that heavy breathing will come from some quarters:

Non-standard: comma splice

- I love tomatoes, red and yellow ones are my favourites.

Why comma splices trip up readers

Some people don’t know what a comma splice is and don’t care. But plenty do, and even if they don’t know what’s it called, they trip up. For those in the know, comma spliced sentences (sometimes) scream off the page for precisely that reason.

That's because when readers see a comma they're inclined to think, This is the start of a list.

A standard method for showing a reader that they’re coming to the end of a list is to incorporate a coordinating conjunction such as ‘and’, ‘but’, ‘though’ and ‘or’. It acts as shorthand for One more item’s coming. Then there’ll be a full stop.

And so when only two items are separated by a comma, the reader’s expecting at least one more item in that list. When that third item doesn’t appear and the sentence finishes, the reader is jolted because they've placed the emphasis in the wrong place. Try reading these examples out loud:

- Let me tell you about fruit: I like apples, I hate pears but I think oranges are okay. Are we clear now?

- Let me tell you about fruit: I like apples, I hate pears. Are we clear now?

Your intonation likely changed as you read the words 'but I think oranges are okay' because you knew you were finishing a sentence. In the second example, you were left hanging after 'hate pears' and likely hadn't placed the stress correctly.

These kinds of stumbles are a distraction that, even if only for a split second, pulls the reader out of the writing. Now they’re thinking about where they placed the emphasis, not about our fabulous learning tool, enthralling plot line or groundbreaking academic research.

When comma splices can work: fiction

Comma splices are probably more prevalent in published fiction, and more acceptable. Sometimes, and with good reason. The comma doesn't always trip up readers.

The key is to allow splices to stand when they serve a purpose.

Narrative and rhythm

Take this example from A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens: ‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity’ and so on.

This prose is an experiment in rhythm. The splices work. But something else is going on too – the anaphora.

Anaphora is a literary device that uses repetition for rhythmic effect. In the Dickens example, the repetition of 'it was' pulls us along on a beautiful booky wave. Editing in semi-colons or full points would destroy the rhythm and would qualify as an example of editorial hypercorrection.

For a more detailed examination of anaphora, read: What is anaphora and how can you use it in fiction writing?

Dialogue and mood

While a comma splice will stick out like a sore thumb in a piece of academic research or an education textbook, that’s not always the case in dialogue.

If the speech is truncated, or there's anaphora in play, a comma might well work. Imagine this scenario in a novel: two characters are having an argument. One says, ‘It’s not me, it’s you’.

Strictly speaking, that's a comma splice. There are two independent clauses with a comma. Would it bother you? Probably not. The speech looks and sounds natural to the mind's ear. Changing the comma to a full stop would slow down the rhythm of the character’s speech and affect the emotionality in the dialogue.

But most important, readers won't trip up; they'll place the emphasis correctly. And so while emotion and mood have been respected, this hasn't been at the expense of clarity.

Summing up

- Understand what a comma splice is. Only then can you make an informed decision about whether to let it stand or fix it.

- Read the sentence aloud, tor ask someone else to. If you or they stumble over what you’ve written, so might your reader.

- Just because Woolf, McCarthy and Dickens use comma splices doesn't mean every writer should. There may be other literary devices in play or narrative motivations affecting their choices.

- There is a grammatical standard for how commas are handled between two independent clauses, but even so, we can’t prescribe for always right or always wrong. Sometimes it’s about style, rhythm and flow.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Find out more about ...

- Correct or conventional – a linguist’s perspective

- Better versus standard

- Zombie rules, and what we can ditch

- Youth language – dumbing down English or enriching it?

- Young people's language in relation to identity and language change

- Varieties of English in written communication: globalization, national and cultural identities

- The internet’s impact on pedantry and peevery

- The relationship between knowledge and pedantry

- The difference between preferences and judgements

- Recognizing our own pedantry and respecting contextually appropriate style

- Stepping outside our linguistic comfort zones

Mentioned in the show

- Radical Copyeditor blog

- ‘The Business of Being a Writer, with Jane Friedman’

- Rob Drummond Linguistics

- TED Talk: 'John McWhorter: Txtng is killing language. JK!!!'

- Rob's graph: Linguistic knowledge versus linguistic pedantry

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Here’s an overview of the present tense, with basic examples:

- Simple present: I write a novel; he writes a novel

- Present progressive (also called present continuous): I am writing a novel; he is writing a novel

- Present perfect: I have written a novel; he has written a novel

- Present perfect progressive: I have been writing a novel; he has been writing a novel

The present is immediate, and that right-nowness forces the reader to stick close to the viewpoint character. We’re in the moment with them. That’s why it appeals to some fiction authors, and why others find it restrictive.

With second-person viewpoints, the present tense is intensely voyeuristic, invasive even. Here’s an excerpt from Iain Banks’s Complicity (p. 60). This is a transgressor narrative with a difference – the narrator is anonymous, at least until later in the novel:

|

You stand up, reach forward and take the neatly folded handkerchief out of the breast pocket of his jacket, flick it open and wipe the blade of the Marttiini on it until the knife is clean. The knife comes from Finland; that’s why the name has such a strange spelling. It hasn’t occurred to you before, but its nationality seems appropriate now and even funny in a grim sort of way; it’s Finnish and you’ve used it to finish Mr Persimmon.

|

And in this example from a later chapter (p. 90), we’re back with the protagonist. Here, the main narrative tense is present. The viewpoint is first-person:

RECOMMENDATION

The present tense is great if you want to shorten the distance between the reader and the viewpoint character.

Present tense works particularly well for short fiction because space is limited. I use it often in my own shorts and flashes because it enables me to pack an immersive punch quickly.

However, it’s tricky to manage if there are multiple viewpoint-character chapters or sections, all operating in the present tense. You’ll need to keep a close eye on the timelines so that the reader’s clear on what ‘now’ really means. If your plot twist hinges on deliberately duping them via your use of tense rather than story craft, you’ll break their trust.

The present tense can also be tiring for readers because it’s emotionally immersive. If you’re writing a novel, you might consider using it only for certain viewpoint characters – your transgressor or victim, for example.

In Let Me Lie, Clare Mackintosh mixes it up: the Anna-viewpoint chapters are set in first-person present; the Murray-viewpoint chapters are third-person past.

The past tense

Now let’s turn to the past tense, starting with some basic examples:

- Simple past: I wrote a novel; he wrote a novel

- Past progressive: I was writing a novel; he was writing a novel

- Past perfect: I had written a novel; he had written a novel

- Past perfect progressive: I had been writing a novel; he had been writing a novel

- Habitual past: I would write a chapter every week; he would write a chapter every week; I used to write a chapter every week; he used to write a chapter every week

The past tense is the choice of most contemporary commercial fiction writers. What’s interesting is that readers are so used to this style that they can still immerse themselves in a past-tense narrative as though the story is unfolding now.

Here’s an excerpt from T. M. Logan’s 29 Seconds (p. 73). We’re given a past-tense narrative with a third-person limited viewpoint (Sarah’s):

WHEN PAST TENSE FLOPS – UNDERSTANDING PAST PERFECT

Less experienced writers can end up in a pickle when referencing events that happened earlier than their novel’s now.

The crucial thing to remember is that when we set a novel in the past tense, anything that happens in the story’s past will likely need the past perfect, at least when the action is introduced.

|

What you want the reader to experience

|

What tense you should write in

|

|

Now – the present of your novel

|

Simple past or past progressive

(she stood; she was standing) |

|

Something that happened before now (i.e. in the novel’s past)

|

Past perfect

(she had stood; she had been standing) |

|

She stood there for a moment, taking in the white Christmas lights Samantha had wound through the slats of her bed’s headboard, and the fuzzy green-and-blue rug the two of them had found rolled up by the curb of a posh apartment building on Fifth Avenue. “Is someone actually throwing this out?” Samantha had asked.

|

When we’re told that ‘She stood’, that’s the novel’s now. But when the narrator recalls events that happened further back in time (bold) – Samantha’s decorating her bed, and the two women’s procuring a rug – these need to be anchored in the past-perfect tense: had, had been.

When authors fail to anchor past events in a novel whose now is already set in the past tense, the reader will be confused.

RENDERING BYGONE ROUTINE – UNDERSTANDING HABITUAL PAST

Now and then, you might want to reference events from your novel’s past that happened routinely or habitually. This is where the habitual past tense comes into play, and the tools are would and used to.

This excerpt from The Templar's Garden by Catherine Clover illustrates the usage. The narrative is set in third-person past but the viewpoint character is recalling regular journeys taken earlier in her life:

And in Time To Win (p. 62), Harry Brett uses the simple past and past progressive for the most part, but then Frank, the viewpoint character, recalls something he’d done habitually in former times:

|

Tatty was talking to Simon. Frank couldn’t hear what they were saying. He looked down the road, towards the harbour and the dead end, the industrial buildings laid low by the unexpected weight of late summer sun, and somewhere over to his left the top of Nelson’s Monument, clear of cloud for once. He used to enjoy driving down South Denes Road and curving back round onto South Beach Parade, accelerating past the old Pleasure Beach and into a different era.

|

Like the past perfect, the habitual past acts as an anchor, so that readers don’t mix up the reminiscence of a routine event with the novel’s now.

To see that confusion in action, replace ‘used to enjoy’ with the simple past: ‘enjoyed’. It reads as if Frank is enjoying driving down South Denes Road right now.

If you don’t want to use the habitual past, then an alternative anchor is necessary. Here I’ve added an anchoring clause and changed the tense to past perfect (he’d, or he had):

- Back in the day, he’d enjoyed driving down [...]

RECOMMENDATION

The past tense is flexible; it’s easier to shift narrative distance (the distance between the reader and the narrator) than is the case with the present tense, though this does increase the risk of flatter writing. Dramatic scenes – fights, escapes, arguments – could end up laboured if the writing isn’t lean and rich.

Still, it’s traditional and readers are used to it. No one will get tired of reading in the past as long as the line craft is strong.

Do take care, however, with rendering events that have taken place in your novel’s past. Use the past perfect or the habitual past when necessary to ensure your readers know what happened when.

Summing up

Write in the tense you feel most comfortable with, and that you think readers of your genre will be most comfortable reading. The past and the present both have their challenges and their advantages. The most important thing is that readers know where and when they are in the story.

Cited sources

- 29 Seconds, T. M. Logan, Zaffre, 2018

- Complicity, Iain Banks, Abacus, 1994

- The Templar’s Garden, Catherine Clover, The Holywell Press, 2017

- The Wife Between Us, Greer Hendricks and Sarah Pekkanen, Pan, 2018

- Time to Win, Harry Brett, Corsair, 2017

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Use them purposefully in your writing when they bring clarity, but remove them when they create clunk.

The fiction writer – and the fiction editor – who takes a formulaic approach to the treatment of adverbs is heading for trouble.

A note on form

Not all adverbs end in –ly (e.g. backwards, inside) and not all words ending in –ly are adverbs (e.g. deadly is an adjective and anomaly is a noun).

That’s one good reason not to eradicate all –ly words from your writing.

To work out whether a word or phrase is behaving adverbially, focus on what it’s modifying not on how it’s spelled.

Verb and adverbs – a quick refresher

A verb is a doing word; it describes a physical or mental action or state of being.

- He swam in the sea.

- That young boy believes in fairies.

- My throat hurts.

- She considered the question and responded accordingly.

- It appeared from nowhere.

- ‘It was a joke, you fool.’

An adverb is a word that describes a verb (just as an adjective describes a noun).

- To boldly go where no one has gone before.

- Mr Bradshaw died suddenly.

- He spoke eloquently.

- ‘James, sit there.’

- She blinked rapidly.

- Roy leaned backwards into the chair.

An adverbial phrase behaves in the same way but uses two or more words to describe the verb (or verb phrase).

- Jonas sat in silence.

- He laughed like a hyena.

- The guy’s been shot in the back.

- Maria stomps her feet in fury.

- We strolled under the light of the silvery moon.

Clunk: Telling us what we already know from dialogue

Here are four examples where the adverb (in bold) attached to the speech tag is redundant because the information in the dialogue does the same job:

- ‘Hand over the fifty thou by Thursday or I’m telling your wife,’ she said threateningly.

- ‘That’s your final warning, son,’ said Jake in a cautionary tone.

- ‘I mean, really, it’s a privilege to breathe the same air as you!’ he said gushingly.

- ‘Take it or leave it – I couldn’t care less,’ said John dismissively.

These aren’t rules but guidelines. Test it. Remove the adverb and read the sentence aloud. Is the intention still clear from the dialogue you’ve written? If so, great – you can lose the adverb. If it’s not, can you recast the dialogue? Consider the following:

- ‘Take it or leave it,’ said John.

- ‘Take it or leave it,’ said John dismissively.

- ‘Take it or leave it – I couldn’t care less,’ said John.

- ‘Take it or leave it – I couldn’t care less,’ said John dismissively.

In (1), dialogue and supporting speech tag seem a little flat. In (2), the adverb helps us to understand John’s mood. In (3), we lose the adverb but the mood intention is supplied by the additional dialogue. In (4), the adverb repeats the mood intention.

None of above four examples is grammatically incorrect, but (1) is possibly underwritten and (4) is definitely overwritten.

Context is everything though. If you’re writing a high-octane crime-thriller scene in which the pace is fast and furious, (1) might just be perfect, (2) and (3) would slow the reader down, and (4) would still be a non-starter.

Clunk: Telling us what we already know from the speech tag

Here are three examples where the adverb (in bold) is redundant because the verb (in italic) provides the same information:

- ‘I love you,’ she whispered softly.

- ‘Stop it at once!’ she yelled loudly.

- ‘I don’t understand. Are you sure that’s right?’ she asked questioningly.

‘Said’ is a rather delicious speech tag because it’s almost invisible. (For an examination of tagging, read: ‘Dialogue tags and how to use them in fiction writing’.)

Readers are so used to seeing ‘said’ that they slide over it without a glance. And that means they stay immersed in the conversation on the page, which if you’re writing dialogue is exactly where you want them.

Clunk: Telling us what we already know from the verb

Here are three examples where the adverb or adverbial phrase (in bold) is redundant because the verb (in italic) provides similar information in the narrative:

- Magne galloped quickly across the heath.

- She inched step by step down the narrow alley.

- He gasped breathily as Mark’s lips grazed his neck.

Slips like these can occur because the writer is still learning to trust their reader. They fear there are too few words or that the description isn’t rich enough. And sometimes writers just run away with themselves, so deeply are they immersed in the world they’ve created and what their characters are experiencing.

This is why drafting and redrafting are so important, and why a fresh set of professional eyes can give the writer courage. I hire people to check most of my own writing because I know that even when I’m writing educational non-fiction I’m so desperate to get my point across that I can sometimes end up in a right old tangle!

Self-editing is hard – professional editors know this. Don’t beat yourself up if you’re prone to double tells – you’re only human. Instead, cross-check your adverbs against your verbs to make sure you’re not repeating yourself.

Clunk: Dragging us away from immediacy

Some adverbs like suddenly, immediately and instantly can do the opposite of what's intended. Overuse can make the action less sudden, less instant. I cover this in detail in Why ‘suddenly’ can spoil your crime fiction: Advice for new writers.

In brief, these adverbs can act like taps on the shoulder that prevent the reader from moving through a story at the same pace as the character. The suddenness of the action is told to us first instead of being experienced by us.

Compare these examples. They demonstrate how removing the adverbs can leave the immediacy of events intact.

A damp mist had settled but he was snug enough. The parka would keep the edge off until the sun rose.

Suddenly, the phone trilled in his pocket, jolting him.

WITHOUT:

A damp mist had settled but he was snug enough. The parka would keep the edge off until the sun rose.

The phone trilled in his pocket, jolting him.

WITH:

Jimmy immediately slammed on the brake, fighting with the wheel as the car careened around the corner.

WITHOUT:

Jimmy slammed on the brake, fighting with the wheel as the car careened around the corner.

Purposeful adverbs

Adverbs, used well, can show motivation, indicate mood, and enrich our imagining of a scene.

I love books that tell it straight because every word pushes me forward. David Rosenfelt is a writer who never disappoints. His Andy Carpenter series features a tenacious lawyer with a dry wit.

The author’s prose is sharp as a knife. Does he use adverbs? Absolutely, though sparingly and they’re always purpose-filled.

|

‘Most of that time we’ve been in my house, which I’ve selfishly insisted on because that’s where Laurie is. Kevin had no objections, because it’s comfortable and because Laurie is cooking our meals.’

(Play Dead, p. 119. Grand Central Publishing; Reprint edition, 2009) |

MOTIVATION:

The adverb tells us about the emotional motivation behind Carpenter’s insistence (Laurie is his lover), which contrasts with Kevin’s motivation: convenience. |

|

‘I accept his offer of a glass of Swedish mineral water and then ask him about his business relationship with Walter Timmerman. He smiles condescendingly and then shakes his head.’

(New Tricks, p. 110. Grand Central Publishing; Reissue edition, 2010) |

MOOD:

Removing the adverb might lead us down the path of thinking that Jacoby, the smiler, is being congenial. He’s not. The scene is confrontational, though measured. |

|

‘Milo is digging furiously in some brush and dirt. The area has gotten muddy because of the rain, but he doesn’t seem to mind.’

(Dog Tags, p. 291. Grand Central Publishing; Reprint edition, 2011) |

SCENE ENRICHMENT:

The adverb enables us to imagine how manic the dog is – we can see his legs pumping, muck flying everywhere, perhaps some doggy drool swinging from the corners of his mouth. That single modifier enriches the narrative. |

Use adverbs when they help your reader understand more than they would have without them. A well-placed adverb or adverbial phrase will help you keep your prose leaner because it will nudge a reader towards imagining the action, the mood of the characters and what their intentions are.

If they’re repetitive clutter that add nothing we couldn’t have guessed, get rid of them. If the narrative or dialogue feels flat, head for a thesaurus and find alternative verbs that will bring your prose to life.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

One of the most common problems I encounter is overwriting. That’s not because the authors are poor writers. It’s because they’re nervous writers.

It takes a lot of hard graft to put enough words on a page to make a book. Yet it takes an equal amount of courage to remove them ... or some of them.

‘What if the reader just doesn’t get it?’

‘What if they’ve forgotten what I told them above?’

‘What if I haven’t provided enough detail?’

‘What if I just love both ways I’ve said that?’

These are the kinds of questions that result in anxious authors bulking up their prose.

In a bid to help you trim the fat, I’m going to explore the following:

- Trusting your reader

- Feisty fragments and snappy shorties

- Damage by dilution

- Letting go of what you love

Trusting your reader

The issue is sometimes one of trust – in the author’s own writing and in the reader’s ability to fill in the gaps. Some genres of fiction lend themselves well to more flowery prose that goes off at a tangent for a moment, a little narrative indulgence for the purpose of artistry or even titillation.

Crime fiction, however, is all about the page turn. That doesn’t mean that the description isn’t rich, but there is an expectation of forward momentum. Avid readers of the genre love it for the thrill of the ride.

Great characterization is key, of course. We want the protagonist to draw us in, the antagonist to pique our curiosity, and the supporting cast to deepen the picture, but ultimately we want to know whodunnit.

And that means we want words that help us understand what’s happening, why, where, who’s doing it, whom it’s being done to, why it’s being done, and how it feels.

And we only need to be told once. We might need a little clarifying nudge here and there but we’re capable of extracting a lot with less than you might think.

Feisty fragments and snappy shorties

If you’re trying to evoke tension in your reader, short sentences and fragments can be very effective.

Look at the following examples and notice how the authors keep their narratives lean.

Here’s an excerpt from Gone Bad by JB Turner:

|

‘When the first shards of sunlight peeked over the horizon, the old man drove Cain nearly a mile down a back road to a clearing in the woods. It was a makeshift shooting range. The targets were life-size mannequins. More than two hundred yards away. He pulled the rifle from the backpack confidently. Had it locked and loaded in seconds.’

|

He might have given a more detailed description of the forest – its sounds and smells. He might have delved deeper into Cain’s emotions, or helped us to picture the backpack by detailing the colour, make, number of pockets and zips, and where the ammo was being held. He could have told us, word for word, how Cain loaded the gun, how careful he was, which bullets he used.

But he doesn’t. Turner leaves it to us to imagine the woods, to see in our mind’s eye the loading of the rifle, and to sense the cold hard determination of the shooter. And the backpack gets no more than a passing mention, because to do more would slow the pace and act as a distraction.

And the result is just right – Goldilocks would approve.

Now consider the choppy fragments in Jens Lapidus’s Life Deluxe:

|

‘Jorge nodded at Mahmud, winked. Signaled: I see you, bro. They needed to talk about tomorrow. J-boy could hardly wait. Something big might be in the works. A step back into G-life. Away from M-life. M as in muffins.

[...] Babak was coming towards him. Open arms – fake smile. The Iranian hugged him. Pounded him on the back. Cut him with verbal knives. [...] Babak’s attitude: irritating like a mosquito bite on your ass. The glitter in the Iranian’s eye. His tone of voice: like being spit in the face.’ |

Lapidus dares to trust us, dares not bore us. And because of, rather than despite, the short sentences and fragmented prose, reading the scene is an immersive experience for the reader. I recall a sense of taut fatigue as I read this book, like I was right there, ever watchful, on my guard.

This author’s deliberate punctuation choices and choppy style mean the word count is reduced but the tension is heightened. He doesn’t pad his narrative with purple prose and stage direction. Like Turner, he trusts us to do the work.

Damage by dilution

Consider your own writing. Leave your draft alone for a few days. Then return to it and see what happens if you take a more reductive approach to a scene.

It's all about balance at the end of the day. Not too much but not too little. Howard Mittelmark & Sandra Newman write:

Neither am I suggesting you avoid creating emotive scenes that are high on tension.

Rather, might you build this tension with shorter, tighter sentences that demand your reader do some of the work?

And I’m not suggesting you should limit every sentence in your book to five words – not at all. I’m suggesting that you might use this technique when you think it would work, when it would push your reader forward, when fewer words – the right words – would work as well or better than more, especially if you know you tend to overwrite.

Letting go of what you love

For some authors it’s not about trust, but about not wanting to let go. Perhaps you found two delicious ways to say the same thing and now you can’t bear to cut either. Or you constructed a stunning paragraph but it’s interrupting the conflict or the action.

In The Magic of Fiction, veteran editor Beth Hill says:

- Precision: Use specific descriptive nouns and verbs that are appropriate to the scene and to the character’s voice.

- Finesse: Eradicate waffle from phrases so that they’re 'pitch perfect' – use punctuation and words that match the mood: harsh scenes could benefit from words that are pronounced harshly and contain hard consonants.

- Length: Play with ‘short and punchy words and short, hard-hitting phrases and incomplete sentences’.

It’s tricky for some beginner writers, I know, but repetition and interruption mean there are redundant words in your writing. And to make your novel sparkle, you need to let go of them because they’re not adding something new, they’re not in the right place, or they’re in the way.

Take courage. Try it with and without. You might be surprised.

- Gone Bad. JB Turner. No Way Back Press, 2015

- How Not to Write a Novel. Howard Mittelmark and Sandra Newman. Penguin, 2009

- Life Deluxe. Jens Lapidus. Pan, 2015

- The Magic of Fiction, 2nd edition. Beth Hill. Title Page Books, 2016

If you'd like to access more tips and resources for self-publishers, visit the Self-publishers page on my website. Try these in particular:

- 5 tips for writing about physical pain in fiction

- 11 things that helped me succeed as a self-published author

- Crime fiction subgenres: Where does your novel fit?

- How to be a better writer: Using a growth mindset to hone your craft

- Slipping into character – understanding the impact of narrative point of view

- What's the difference between a rule and a preference?

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

BLOG ALERTS

TESTIMONIALS

Dare Rogers

'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'

Jeff Carson

'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'

J B Turner

'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'

Ayshe Gemedzhy

'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'

Salt Publishing

'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'

CATEGORIES

All

Around The World

Audio Books

Author Chat

Author Interviews

Author Platform

Author Resources

Blogging

Book Marketing

Books

Branding

Business Tips

Choosing An Editor

Client Talk

Conscious Language

Core Editorial Skills

Crime Writing

Design And Layout

Dialogue

Editing

Editorial Tips

Editorial Tools

Editors On The Blog

Erotica

Fiction

Fiction Editing

Freelancing

Free Stuff

Getting Noticed

Getting Work

Grammar Links

Guest Writers

Indexing

Indie Authors

Lean Writing

Line Craft

Link Of The Week

Macro Chat

Marketing Tips

Money Talk

Mood And Rhythm

More Macros And Add Ins

Networking

Online Courses

PDF Markup

Podcasting

POV

Proofreading

Proofreading Marks

Publishing

Punctuation

Q&A With Louise

Resources

Roundups

Self Editing

Self Publishing Authors

Sentence Editing

Showing And Telling

Software

Stamps

Starting Out

Story Craft

The Editing Podcast

Training

Types Of Editing

Using Word

Website Tips

Work Choices

Working Onscreen

Working Smart

Writer Resources

Writing

Writing Tips

Writing Tools

ARCHIVES

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

October 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022