|

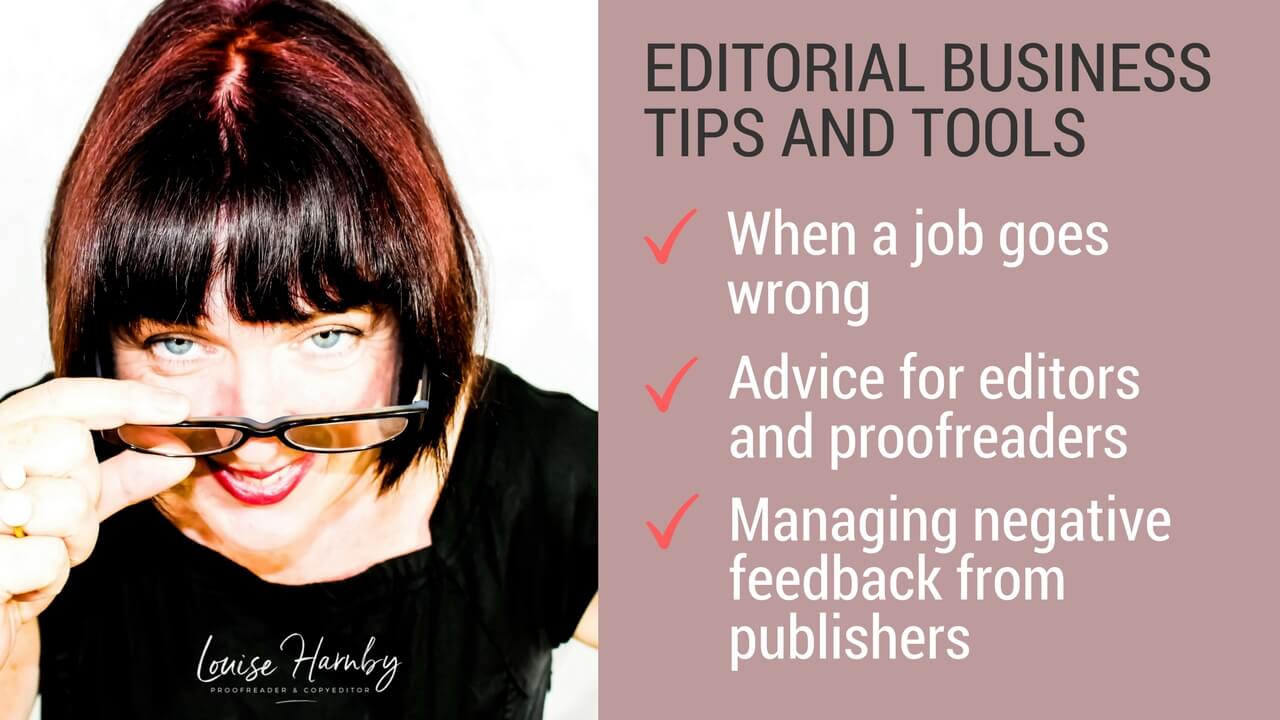

An in-house editor discusses how he handles receipt of substandard work from a freelancer. Also worth noting is his advice on how a freelancer might interpret a lack of contact from an in-house editor and what to do about it ...

Philip Stirups sheds light on his experiences of editorial production. To be clear, Philip’s contributions are from the point of view of a publishing professional, broadly speaking. So while some of the things he has to say are informed by his experiences within the UK company for which he currently works, his residency here is not in the capacity of a representative of that particular publishing house. Over to Philip ...

At the outset, I want to say that the majority of proofreading jobs I receive back from freelancers are good. However, in a handful of instances, a job comes back and, unfortunately, it isn't up to scratch. Problems could include:

From an editorial perspective, this can cause an array of different problems. First, an unsatisfactory proofread will usually lead to the in-house editor having to step in to compensate, which can in turn have an adverse impact on the book schedule. A second problem, from an in-house editorial perspective, is even trickier: how to give feedback in an honest, yet tactful, way. Breaking the bad news … On the surface, the simple solution to this seems to be: "tell it as it is". However, this is easier in theory than in practice. The problem is that it’s quite difficult to convey tone via email. I want to get across what has been missed, but in such a way as not to seem condescending. Furthermore, I don't want the freelancer to go away thinking they've done a bad job, when overall they haven’t. I could use the phone in order to avoid tone problems. However, I believe that an email is more beneficial to the freelancer because it provides them with a written record of the issues; this means they have something to refer back to when they carry out future work for the in-house editor. Receiving criticism, albeit constructive feedback, can be a shock for the freelancer, and very upsetting. I don’t want my suppliers to lose confidence when I have to tell them a job didn’t meet my requirements. Instead, I want to communicate the message in a way that enables them to move forward, strong in the knowledge that by attending to the highlighted problems our working relationship can continue satisfactorily. Email gives them the time and space to digest the feedback I've offered in a non-confrontational way. In cases where the work continues to be substantially below expectations, the clearest feedback a freelancer will receive may be represented by them not being offered further work. This isn't to say that, overall, they are not good at what they do – rather, each job needs to be assessed on an individual basis, and when a freelancer is unable to use critical feedback to meet the in-house editor’s needs, the editor may decide that the supplier is no longer a good fit. Things aren’t always what they seem … Being offered no work, or only intermittent work, is not always an indication of poor fit or poor-quality work. It can often simply be, as I have often experienced, a case of there being no work available at the time. Publishers' production workflows vary. A large house, with multiple imprints, that publishes mass-market paperback fiction may have a steady stream of projects to offer freelancers throughout the year, while a smaller independent academic press specializing in social science monographs or student handbooks may have busy and quiet spells in its production process. It may also be that the freelancer had regularly turned down work, owing to the demands of their schedule. In this case, the in-house editor may have taken the decision to focus on other suppliers who are more often available. It’s not a question of poor fit or poor quality; rather, the freelancer has simply slipped out of the in-house editor's mind. If you’ve not been offered work from one of your in-house editors for a longer time than you feel comfortable with, get in touch. It never hurts to drop an editor a message to ask whether they have any projects. The worst they can say is “no”, and even if they don't have anything to offer you now, but are happy to work with you again, you’re back on their radar. Don’t be afraid to ask … I cannot say there is a right or wrong way to give feedback. However, I firmly believe that openness on both sides is the key. I am willing to admit that my freelancer briefs could be improved. If you ever want feedback from your editor, just ask ... And remember: it is never personal; it’s about meeting a set of business requirements. We in-house editors and freelancers are on the same team.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

1 Comment

PerfectIt is one of my favourite pieces of editorial software – a set of mechanical "eyes" that enable me to increase my productivity, consistency and overall quality when proofreading. That means it's good news for me and for my clients. Version 3 of this super software was recently launched. For an overview of what's new, visit the Intelligent Editing website, where all the additional features are explained by the developer. I'd planned to review version 3 here on the Parlour, but I'm a great believer on not reinventing the wheel when someone's already done the donkey work! So when I read fellow PerfectIt user Adrienne Montgomerie's robust review of PerfectIt 3, it made more sense to push my readers in her direction. You can read the article in full here: PerfectIt 3: Quality Software for the Experienced Editor (The Editors' Weekly, the official blog of the EAC). Montgomerie provides a useful overview of the best new features, points of confusion, points of frustration, and an overall verdict. Her final words? "PerfectIt will still save your bacon, can save you time and tends to make you look eagle-eyed. If you take the time to set up style sheets for repeat clients, you can free up your eyes for content issues and lingering style issues. I will definitely be taking the time to make the most of this add-in for my largest clients, and I’ll continue running it on all documents." Louise Harnby is a professional proofreader and copyeditor. She curates The Proofreader's Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn.

An in-house editor sheds light on his experiences of in-house editorial production, including how freelance editors and proofreaders are selected.

This editor's contributions are from the point of view of a publishing professional, broadly speaking. So while some of the things he has to say are informed by his experiences within the UK company for which he works, his residency there is not in the capacity of a representative of that particular publishing house.

Louise: Hi, Philip. It’s great to have you here! First, can you tell us a little bit about yourself? It would be useful to have an overview of your daily responsibilities – many of our readers haven’t worked in-house so they may be unaware of what an in-house editor does. I understand that different presses work in different ways, but it would still be handy to know what you do.

UE: Hi Louise. It’s equally great to be contributing to your blog. So, a little bit about myself. I started working in publishing straight out of University back in 2010. I studied English and German at the University of Reading – and since my passion is language, publishing seemed like a natural career choice. I have been working in the editorial department of an academic publishing house for the past five years. It’s absolutely incredible how quickly time flies. You are completely right – every publishing house operates in slightly different ways, so I can’t say the experience is representative of the role of in-house editors up and down the country. And, even after five years, I am still rather new to the industry, compared with some of my colleagues, so I don’t speak as the one true voice of experience either. So, about my role … As an editor, I am responsible for the project management of up to fifteen social science/humanities titles at any given time. My ultimate responsibility is ensuring the standards of the final product are in keeping with company and author expectations. One thing that makes my role unique is that I, as an in-house editor, am responsible for typesetting my own projects. It is absolutely fantastic to feel so involved with a project from day one to the nerve-wracking day the book is ready to be sent to print. There is nothing better than having a satisfied author! Louise: Which editorial services do you currently contract out to freelancers? Structural/development editing, copy-editing, proofreading, indexing? Anything else? UE: We have three routes to print:

Louise: Today, I’d specifically like to focus on the commissioning of new freelancers. One question that comes up a lot in the freelance editorial community is: How does one get noticed by publishers? So do you use particular directories when you’re looking to source new suppliers, and if so which ones? Or do you consider freelancers who’ve contacted you direct (by email, telephone, letter)? How about referrals from colleagues working for other presses? UE: In collaboration with my line manager, I am responsible for curating the freelancer pool and enhancing freelancer processes, so I feel I can answer this question definitively. The best way to get noticed by a publishing house is simply by finding out who the relevant in-house contact responsible for the freelancer pool is, and then sending them a quick message to enquire about the process. If you don’t ever ask, you’re never going to know. Granted, a lot of publishers have established pools of people they use. However, I feel that you can never have too many freelancers in your pool – especially law proofreaders, who understand OSCOLA referencing. A CV and covering letter is a good base from which to start, but I’ve met freelancers in person to whom I have offered work. For example, I made new contacts off the back of attending the Society of Indexers (SI) conference in Cirencester in 2014, and many more at the joint Society for Editors and Proofreaders (SfEP)/SI conference in York in 2015. As an in-house editor, I would offer the following two key pieces of advice to any editorial freelancer:

Louise: When you read a CV and covering letter, or view someone’s listing in a membership directory, what are the key stand-out points that you're looking for? Here, I’m thinking about the skills, experience, training, and other qualifications that make you think, “Yes, that person’s someone we want in our freelance bank.” When I announced the launch of this column, two of my colleagues asked specific questions that relate directly to these issues. Just as a reminder I’ve included them here:

UE: It is a combination of different factors that determines whether a particular person is suitable for our freelancer pool. Since we have a quite full freelancer list, freelancer specialities tend to be significant. A good freelancer should be able to work on a variety of different material, but it is always good having somebody who really understands the text. Law, for example, tends to be one of those lists with a lot of subject-specific terms, and it is always good when these are understood in context. Having professional accreditation is desirable. For example, with indexing we look for membership of the SI, and with proofreading we look to the SfEP. Louise: How important is prior publishing experience, broadly speaking? If a freelancer has worked in-house, is this a strong selling point for you? Even if they haven’t worked in-house, is it important that they’ve worked for other publishers? I’m interested in your views on this because I’m often asked by new entrants to the field whether a lack of publishing experience means it will be more difficult for them to secure work with publishers. UE: In general, prior experience is important to in-house editors. If I see that a freelancer has worked for a particular client with similar lists to ours, then I will assume some level of familiarity with the subject matter. Professional accreditation is great, but experience is what can bring these qualifications to life. I understand that this is often one of the hardest things for new freelancers. They want to gain experience, but in order to do so they have to be given work. And to be given work, they need experience. You see where the problem is! I do therefore respect the fact that everyone has to start somewhere. You can often get a feeling from initial exchanges with freelancers whether your work together is going to be fruitful – call it editor’s intuition. Since all publishing houses work in different ways, it generally takes a couple of projects to get freelancers up to speed with working processes, but, by and large, the results are very pleasing. Louise: Finally, do you have any further advice you’d like to share with freelancers who want to acquire work with publishers? UE: Great question – I would say the following are points to bear in mind for anyone looking to acquire work:

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses. Dear valued proofreaders and editors, Louise has presented a wide range of business and editing advice here on the Proofreader's Parlour. Some of it I refer to regularly. What I hope to contribute is an understanding of what developmental editors (macro level/substantive changes) do in the school market. That means the textbooks, handouts, exams and such that kids get day to day at school. First, I hope this insight will be interesting. Second, I hope it will alert everyone down the line in the publishing process to the intricate web of concerns that are woven into today's textbooks. Grab a cuppa and listen in. Most of the resources I work on are for the K–12 school market in Canada and the USA. That covers all schooling from the first days until university or college. Chemistry and physics topics make up most of my work; math comes after that. Though I am a certified copy-editor, substantive editing is so time consuming that it makes up the majority of my practice. That explains my POV. When material finally makes it to the copy-editor (and afterward, to the proofreader) it has been massaged to an astounding extent. Less of the author’s voice is left in these materials than in most others. The editors have taken into account:

That's off the top of my head. There's definitely more. Any changes I suggest had better move the manuscript closer to those goals. Reading level is high on my list of concerns when copy-editing. Because I edit tough subjects, it's important that the language not get in the way of the learning. Often we are aiming one full grade level below the audience. I have edited chemistry to the cadence of Green Eggs and Ham, and physics to the rhythm of Sherlock Holmes. Occasionally, another copy editor will “smooth” the language of a piece, raising the reading level eight years above the education level of the audience. There was a reason it was written that way. The style sheet in school products reflects current trends in education, propriety, and avoiding any possible sense of moral, ethical, or legal infraction. I have removed the image of a sculptor because he was working on a backside, I've struggled with wording about erecting structures, and I've flipped the terms Aboriginal with Indigenous because none of the consultants seemed to agree. I have also taken indigo out of the rainbow, and mourned the loss of Pluto’s planet designation along with the rest of my generation. Learning new things is one of the best perks of editing. Working on school materials brings a broad wealth of information to your screen. And the author’s enthusiasm? You can sense that from the sheer number of exclamation marks. My husband once admonished me: “If you’d worked that hard in school, you’d have done much better.” Well, they weren't paying me to go to school, and they didn't give me six solid months to work on one text. A lot has changed.  Adrienne Montgomerie is a freelance editor in Canada where she lives on the shore of one of the largest lakes in the world, Lake Ontario, and enjoys time outdoors in all weather. She is a phonics app developer and a certified copy editor who works mostly on instructional material. You can learn editing tricks from her in online courses and in a weekly column at Copyediting.com. You can also listen to her posts on the Right Angels and Polo Bears podcast. Note from Louise: I've been charmed in the past two weeks – three special guests sharing their wisdom on the Parlour! This time it's my colleague Sophie Playle. Sophie and I met at our SfEP local-group meeting in Norwich. She's a talented writer (more on that in a future post) and has a very specialist skill set within her service portfolio – manuscript critiquing. I asked Sophie if she'd tell us a bit more about it, and she kindly obliged ...  How I ended up offering a critiquing service My journey to where I am now – a freelance writer and editor who offers critiquing (or manuscript appraisal) as one of my services – evolved partly organically, and partly with focused purpose. It's a familiar story, but I have always wanted to write. At school, I never really knew what I wanted to do with my life in terms of career, but I did know that I loved the escapism of books and the swooning elegance of language. While choosing a university degree, I followed my passion and went for the English Literature with Creative Writing BA offered by the University of East Anglia. I loved the writing element of the course more than anything, and from my first to my final year, I went through a steep learning curve. Our final-year creative writing group consisted of a small core of writers. We would write short stories and submit them for our fellow group members to tear apart. It was invigorating. We all knew the value of criticism, and both craved and respected the feedback we received, eager to improve our craft. It was a tough but safe bubble. In one of my private tutorials, my tutor complimented me on the quality of my feedback to other students (our feedback contributed 10% to our grade, but I was more motivated by the thought of genuinely helping my fellow writers). She asked if I had ever considered a career as an editor. Getting this endorsement certainly gave me encouragement, and nudged me towards my future career. Leaving university, I began to apply for jobs at publishing houses for entry-level editorial assistant jobs. I also began a long distance-learning course in copy-editing. Eventually, I landed a full-time role at a large educational publisher. Before long, however, I was craving fiction and creativity and writing again. So I decided to take the plunge and do an MA in Creative Writing at Royal Holloway, University of London – while still keeping in touch with my publishing house for the odd freelance project. The focus of my MA was novel writing, and each of us on the course was plunged into the task. As with my final-year undergraduate class, each week we would critique each other's work – from sentence-level, language and grammar issues to the developing bigger issues such as point-of-view and voice as our novels progressed. Much of our course was also focused on reading and analysing critical theory related to literature and the craft of novel writing, so that our constructive criticism had a sound academic foundation. I absolutely loved the experience, and my writing and editing skills developed dramatically in the challenging environment. During my time working in publishing, I also set up my own literary publication called Inkspill Magazine. I decided to host a short-story competition, where all entries received a free critique, to test my critiquing skills in the real world. I received lots of positive feedback and, upon completing my MA, I decided to offer critiquing as a freelance service to writers. My academic foundation and publishing experience (and the various tests I set myself) provided me with the confidence to offer a critiquing service. So, what is a manuscript critique? A critique sounds a bit daunting, akin to the word criticise – but it's not a harsh deconstruction. Essentially, a critique looks at the "big picture" elements of a manuscript (plot, pace, characters, voice, etc.) and offers a constructive analysis, with the aim of showing where the writing succeeds and where it could be improved, to better inform the writer's next step. It is often called a Manuscript Appraisal, but I favour the term "Manuscript Critique" because what I provide goes beyond an assessment, also offering possible ways to address the issues I might highlight. The critique is offered as a report, which is usually between 5 and15 pages (though I have written reports of up to 25 pages) depending on how many issues I feel need to be addressed, or depending on the length of the manuscript. It doesn't include any sentence-based editing, though if there is a recurring issue throughout the manuscript, I would flag it up within the report as a general area to look at. Who are the clients? Most of my critiquing clients are writers on a journey to self-publication, or writers who want to increase their chances of representation for traditional publication. Generally, a critiquing client will be interested in making sure the core of their novel is as good as it can be, and looking for external professional confirmation and/or suggestions for development. This type of assessment comes before any copy-editing or proofreading, and can be used to test ideas (with a sample of the novel plus a synopsis) or strengthen complete novels when the writer feels there is more work to be done but is not sure how to go about it. The benefits of a manuscript critique A critiquing service is not needed for everyone, but it can help a writer gain a professional outside perspective, help them develop their manuscript, provide confirmation of its quality, and help inform the next step of their project – in the worst-case scenario, that might be to put the novel in a drawer and chalk it up to valuable experience, and in the best-case scenario, it might be to immediately send the project out to agents and publishers! (Often, it will be the steps to take for a further draft.) Often, beta readers (friends, colleagues, etc.) can give a writer a useful "big picture" perspective on their writing, but a professional critique goes much deeper – with the added benefit of an honest appraisal (something that might be skewed by kindness from friends!). Writers are often told that they need a thick skin – and that certainly comes in useful with a critique. Though I attempt to critique with the utmost sensitivity and respect, I feel the biggest injustice to a writer would be to offer them hollow advice and empty praise. Sometimes the assessment can be a bit of a shock to the writer, so it is important to remember that the critique is designed to improve the project, and not to negatively criticise the writer as an individual. It's often very difficult to accept that there might be some fundamental issues with a manuscript that will need substantive work, so when a writer sends their novel to be critiqued, I would say: be prepared for some more hard work ahead! Copyright 2013 Sophie Playle Sophie Playle offers writing, editing and critiquing services to independent writers. Find out more: Liminal Pages.

Independent author T.P. Archie recently published A Guide to First Contact, a post-apocalyptic novel set in 2060.

His search for editorial assistance initially led him to me. However, after some discussion about what was needed, we agreed that he’d benefit from an developmental and line editor, not a proofreader. I pointed him in the right direction and he hired one of my SfEP colleagues to work on the manuscript. Now he’s been kind enough to take time out of his busy schedule to talk to the Parlour about this experience, and his independent publishing journey more broadly.

Parlour: First of all, congratulations on publishing your book! Can you give us a short synopsis of the novel and tell us how the idea for Guide came about?

T.P. Archie: Hi. Thanks for inviting me in. Guide alternates between the present day and a post-apocalyptic Earth. On the edge of the solar system, Star Beings plan the next phase of their work. New life. An animite must be hurled onto the third planet. The impact will scatter organic compounds throughout Earth’s biosphere. But there’s a problem: the animite goes missing. A hundred thousand years later, it’s the 21st century. A space mission to a near-earth object makes an amazing biological discovery which is brought back to Earth. This American secret is trumped when France announces contact with creatures from outer space. Then disaster strikes. Technologies in key industries begin to fail. The West collapses … It’s now 2060. Most cities are long abandoned. All that remains of the once-mighty United States is the Petits États, centred on New England. Outside of there, civilisation survives in Enclaves, relying on the confederation of Sioux Nations for protection. For forty years a genetic plague has ravaged humanity. It began just after Earth was contacted by aliens. A new and mysterious power – the mandat culturel – controls access to advanced technologies.

Triste, hopeless with girls, but good with guns, is a bounty hunter. He has all the latest ordnance. His contracts pay well but are dangerous. They take him to the ruined cities; he spends a lot of time in the former urban area of New York.

His current mission is to reconnoitre a long lost laboratory. He encounters a ramshackle band of opportunists whom he sends packing. In doing so, he meets Shoe. They find the lab. It has secrets linking it to the collapse of Western civilisation. Shoe is running from her family. She has other secrets. In the dead shell of Manhattan lurks a secret pensitela base. Their alien biology protects them from the brutal savagery of the place. They have their own reasons for being there. From the edges of the solar system, a Star Being monitors Earth. It has a plan – and Triste meeting Shoe isn’t accidental. His troubles have just begun. Eventually he is faced by the hard truths behind the fall of the West.

At its most basic, Guide is a series of interlinked narratives that combine to reveal how the apocalypse comes about. Other readings are possible. One of my objectives was to explore different kinds of first contact.

However, Guide didn’t start like that. It began as a test of Novel Writing Software – yes, there’s a product really called that! I planned to write three chapters, which I thought would be sufficient for my purpose. So out it churned, an endless stream of 'hero takes on hordes from hell'. At about 8,000 words I took stock. I already knew it wasn’t intellectually satisfying yet I had found a writing rhythm. It occurred to me that while I was in my stride, I should experiment. Why didn’t I add something with a bit of interest? I had a few characters kicking around in my head. "Everyone has a novel in them," I told myself; all I needed was a theme to link them together. In they went; and the violence was trimmed. That was it; I was hooked. I wrote and added themes. There’s gender reversal – the story won’t work properly without it – and Darwin’s theory of evolution (these two are linked). Then the never-ending Anglo-French rivalry; followed by a drip feed of classical Greek philosophy. Each theme had a purpose. Why? I want SF that makes sense, including the cosmogony. Depicting aliens, for example, requires some attention to how they might see the universe. In retrospect, I realise I’d grown away from SF/Fantasy; little of what was available appealed to me. I was sitting around waiting for someone to write the stuff I wanted, which wasn’t happening. Parlour: Could you tell us a bit more about yourself and how you started writing? T.P. Archie: I qualified as an accountant in 1990. My mother was born to a family of Estonian farmers and my father began life as a cobbler. I grew up in a one-parent family. Most of my early life was lived in Stoneyholme, a deprived part of Burnley. My mother rented from a block of terraced houses. There was plenty self-inflicted misery, but it was rarely safe to observe. As the son of an immigrant with a German accent, it was my duty to avoid the occasional beatings that were due to me. Grammar school education informed me that the oppressive reality of working-class life stopped at the edge of the estate. I began reading SF/Fantasy in my teens. This was later complemented by an interest in classical philosophy and history. Once I started writing, I found a great deal to say. Parlour: Who are your biggest influences (from a literary point of view)? T.P. Archie: My formative years were very much influenced by genre authors, e.g. Asimov, Clarke and Heinlein. I continue to be impressed by Tolkien’s myth building and the universe of Frank Herbert’s Dune. Outside the genre I have found Dostoyevsky, Kafka, Pasternak, George Eliot and Doris Lessing to my taste. I am also partial to Plato and the works of Idries Shah. My writing is also influenced by the work of Orson Welles. (Oh, okay – he didn’t really write :) ) By the way, I’m ridiculously pleased with my Philip K. Dick collection, tatty Ace editions and all. Dick is best known for Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, which inspired Bladerunner. Dick didn't need to spell out apocalypse, yet his settings work. His characters think a great mix of the mundane and the profound. Seemingly omnipotent creatures are driven by biology or freely admit their fallibility, as Glimmung does in Galactic Pot-Healer. Many of his works are laced with dark humour and are worth a reread. Parlour: Like many other authors around the world, you've decided to go down the independent publishing route. Self-publishing requires the wearing of many hats in addition to the writing. What have been the upsides and the downsides of this decision? T.P. Archie: Upsides: you control everything. Downsides: you control everything. Okay, that was tongue-in-cheek. The main benefit is that you are in control over the pace of your development. Once you have a deal, you are locked into it. As an indie author, I don’t feel the constraint of writing to fit genre style/house style. Ask the right questions at author events and the strictures of formulaic writing become clear. I've read widely in my chosen genre, including many of its standards. There are many themes to explore/treat differently. The most significant drawback was in the narrative – devising a practical approach to self-editing. While shaping ideas, I’d revisit text. If words didn’t come, I’d use "next best", i.e. placeholder terms, and work it until it was there or thereabouts. This resulted in intermittent problem areas. Sometimes I attempted to clean these up but this was a chore. I’d ask of myself, "What comes through in the narrative? Does it need reshaping?" I was too close to answer that, and a long way from feedback. I moved on. In my heart of hearts, I knew there were better approaches but I lacked the comfort of funds, so investigation wasn't an option. Besides, it was still a hobby. Did I plan to go DIY? I saw no choice. New authors produce first novels. First novels are best kept locked away in a drawer, hoping no one reads them; or (in my case) kept for practice. Many new authors go on to sell a few copies to friends and families. It’s a hobby and a fine one. You learn how to put a PDF together; you Photoshop-up a half-way reasonable cover – and if that doesn't appeal there’s plenty of stock imagery out there. Then you get to make friends with local book-sellers and libraries. Soon your edition has gone from sales of 10 units to say 100 and you can get stuck into decisions such as how many to print (economic order quantity for the business inclined). That’s a long road which begins with up front financial commitment, a dry garage and benign family arrangements. So, back to me – before I spent, how ready was I? How much confidence had I in my book? What was acceptable quality? What did I do to reach that bar? These are big, big questions which each author must decide for themselves. Anecdotal evidence suggests that a high proportion of self-published product doesn't make the grade. The follow on question to this, kind of asks itself: Am I self-critical enough? The only way is feedback. Parlour: So tell us about that. What was your experience regarding feedback? T.P. Archie: Completing that first draft gave me a tremendous burst of energy. There was so much more to write. What did I do? Jump the gun or wait? There were troublesome areas but I was too close to it to deal properly with them myself. I needed feedback and had none. So I seeded drafts to those who thought they might like to read it through, and I waited. I hoped that this would put me in a better position to know if it was worth writing more. It was only hobby time, but I might as well get it right. I waited for feedback ... and waited. It was a long time coming. That time was frustrating, to put it mildly. While I waited, I reacquainted myself with the rudiments of grammar and punctuation. I joined writing groups and reluctantly practised short stories. There’s nothing like reading out loud for finding flaws in your work. Finally I got feedback from my draft. It became clear that I needed to reshape Guide. I realised there was still a long way to go and I had to up my game. The stage points of that journey weren't yet clear. I continue to practise short stories, which, contrary to my initial opinion, gave significant benefit. Parlour: How long did it take to get Guide from the conception stage to the marketplace? I ask because some of the conversations I have with more inexperienced indie writers leave me worrying that they might not be being realistic about the length of time the process takes. T.P. Archie: A quick answer is four years. Could I have done it quicker? No. Longer answer: At the time, I thought I would be finished with the process in six months. Having said that, it’s worth pointing out that my original objective wasn't writing per se. In fact, it didn't matter if I couldn't write; my objective was to test a software package. It was only when I’d "done enough" for that initial purpose (my target was 8k words) that I realised I had something to say. Basically, I was a committed hobbyist who got sucked in. My early view changed from "let’s do 8k words" to "I bet I can finish this off in 60k words". I gave myself three months to get to first draft (it took three and a half) and a further three to tidy things up. This latter goal was totally unrealistic – it assumed a level of proficiency in editing my work that I didn't possess. The three months for first draft misled me because the effort, although considerable, was compacted together. Much longer was needed to give Guide a finished gloss. How long would I allow now? It would make me uncomfortable to imagine I could do it in less than a year. At the moment I’d calculate the minimum time as:

Why all that extra time? There’s little chance that Guide could have been ready earlier than it was. I wanted to get things right. While I waited for feedback there were things I could do that wouldn't be a waste of time. First things first: a test of commitment, learn the ropes. I learned Lulu (POD/ Print on Demand), dabbled with Photoshop, put work into devising blurb, table of contents, copyright, permission to quote. The drip of feedback began. I got stuck into editing. The more I did, the bigger Guide got. It started at 60k words and grew to 80k. Then I received good-quality feedback. A complete rethink was required. I needed to convince myself that there was mileage in the next step. Plusses and minuses two years after first draft would have read:

With hindsight, I now know that my product wasn't ready; I needed to develop as an author. What wasn't clear was how much time was required to become half-way competent. Much of the past four years has been spent looking for feedback and dealing with it. I've a better idea how much work goes into publishing. Using other expertise means you spend more time in your comfort zone. I've spent a lot of time in business, enough to know that I've little interest in activity that adds little value. Successful authors should prioritise and focus on what they’re good at: writing. During this time the stages I went through were:

Parlour: Some independent authors take a completely do-it-yourself approach to the self-publishing process – including the cover design, editing and proofreading. Why did you decide to hire an editorial professional, how did you go about the task, and what qualities were you looking for? T.P. Archie: By 2012 I’d done all I could, Guide could progress further. I rested it. A change of circumstances made that extra investment possible. Browsing on Goodreads gave me the idea that it needed other eyes, and that proofreading might be worth looking into. I ranked proofreaders; you came top. Hiring an editor was a leap in the dark. I’d little idea of how to proceed so I went with gut instinct. Stephen Cashmore became Guide’s editor. Parlour: What were the biggest benefits of hiring an editor? T.P. Archie: It smoothed out my style and helped me understand what worked and what didn't. This has given me confidence in my other projects. Parlour: Any challenges? T.P. Archie: Definitely. The main one was to disengage thoroughly from the story design in mind – i.e. what I meant to convey – and actually deal with the editorial comment. I flip-flopped on some changes; in others, what I thought I needed to do didn't work. At times I needed to check my original intent; fortunately, my notes plus backups were up to the task. I found the editing process to be very helpful. Parlour: If you could do it all over again, would you do anything differently? T.P. Archie: Interesting question. As far as the actual writing goes, things fell out as they did. The main characters had been in my head for some years. I felt little urge to write something I could get over the counter; the piece was always going to become complex. The decisions affecting the outcome couldn't be envisaged until after first draft. Some were merely opportunities, which if not pressed would have held me back – e.g. I pushed for the local writing group to reform, even though I knew little of writing and less of those who would come to make up that group. Selecting an editor was an act of faith but there was a real choice. I wasn't entirely sure how things would progress. Different outcomes were possible – but given a rewind, I’d be unlikely to do anything differently. I still have more to learn. Parlour: Many of this blog’s readers are editors and proofreaders. Is there any advice you’d like to offer to us about dealing with independent authors so that we can do our very best for you? I currently publish a set of Guidelines for New Authors, and, like many other editorial professionals, I'm keen to ensure I offer indie writers the information that’s most helpful to them. So what should we be doing and what might we do better? T.P. Archie: Many potential clients don’t have a literary background and so won’t understand the value of your services. I think it’s worth taking me as an example ... In 2012, Guide had progressed as far as I could take it, yet I was certain that its story was worth extra effort to get it into the marketplace. However, what to do wasn't clear. I had little idea what could be achieved and I put it on one side. I came across the SfEP by accident, while following up a comment made on Goodreads by a US proofreading business. I ran a web search, ranked the results, emailed the top ranking proofreader who helped me find an editor. Encountering you (and hence the SfEP) wasn't a guaranteed outcome. It takes courage for first time indie author to let a professional look at his work. The edit began. Issues were identified and ranked into major/moderate/minor. Changes were proposed. I prioritised my effort. Nearly all the minor changes were accepted without question. Suggestions for other issues were helpful and I followed many of them. Guide had several types of problem. The story structure required a rethink, the style was inconsistent, and the text was too fragmented. In many places, the pace of the plot was let down by the narrative. The benefits from the edit were significant. I put Guide into chronological order. Style excesses and inconsistencies were smoothed out. Fragmented text was joined up. I dealt with problems on a case-by-case basis. Some solutions came from my editor; dialogue translation was provided for the one chapter where Russian is spoken. This added authenticity without detracting from the pace. In another case a solution evolved in the to and fro of the edit – a lengthy dialogue was demoted to the appendices, where it actually plays better. The overall result is more readable. The edit kept me in my comfort zone and solved a major headache; knowing how much to edit, and when to stop, was now solved. I had a better idea of what worked and what didn't. In addition I got an idea of where the boundaries of taste lay (where Guide strays near the edge, it is for story purposes). The whole thing has given me a great deal of confidence; I now know thorny problem areas can be identified and improved. I'm certain my editor would agree with me if I said I was slow on the uptake. For this, and other reasons, what editors and proofreaders do needs to be out there and spelt out. A book on this sounds a good idea. [Editorial freelancers] are more likely to find value from those who are already seeking out their services. Parlour: Having now achieved that final goal of getting your novel to market, what advice would you give to any indie author who’s considering self-publishing? T.P. Archie: Self-publishing requires an author to get a lot of things right. Some of these are tasks with steep learning curves that can take an author away from his/her comfort zone. New authors need to make judgements on where their expertise stops. Where the processes are mechanical (e.g. POD formatting) it is clear if you have this right or not. As far as the actual writing goes, you are too close to your work to make that call. Any indie author seriously considering first-time publication would do well to consider putting it through copy-editing. I plan to do this with my next novel. In the case of Guide some kind of final check was needed. Proofreading seemed a good idea; it actually needed copy-editing. That process was well worthwhile. Parlour: What does the future hold? Do you have plans for future novels, and, if so, will they be in the science fiction genre? T.P. Archie: I have four genre pieces in progress. In 2012, I dared to look forward, on the heroic assumption that Guide could be finished; I asked myself “What I would like to write next?” The ideas I liked were:

I've made starts on each of these. There are also a number of themes coming out of Guide that I would find interesting to follow up. Before that happens I’ll do a little marketing. I'm on Goodreads, where I'm planning a "giveaway". I also want to tell local newspapers about Guide. There’s a press release, some bookstores to visit and, in between, I might read a few extracts onto YouTube. I promised to inform Octagon Press, agents to the written works of Idries Shah, as well as the Department of Public Affairs at Mayo Clinics ... Parlour: Thank you so much, T.P. I think independent authors and editors/proofreaders can all learn a huge amount from the experiences you've so generously shared!

To buy A Guide to First Contact, visit Amazon or Lulu:

You can contact T.P. Archie as follows:

Louise Harnby is a fiction copyeditor and proofreader. She curates The Proofreader's Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. If you're an author, you might like to visit Louise’s Writing Library to access my latest self-publishing resources, all of which are free and available instantly. The Fiction Freelancing series presents the individual experiences of editorial freelancers working on fiction within both the publishing sector and the independent-author market. The Parlour’s Work Choices feature has proved tremendously popular with editors and proofreaders looking for insights into working in various genres and specialist academic/professional fields. This time round we’re looking at editing genre fiction, and sharing his wisdom is my colleague Marcus Trower.  Marcus has an impressive publishing background – journalist, production editor, chief sub-editor, feature writer, film critic, contributor to men’s magazines, travel journalist, and editor. Oh, and he’s written and published a book, too. With this many strings to his bow he knows a fair bit about the written word, so I’m delighted he’s agreed to talk to us about the business of editing … Louise Harnby: Welcome to the Proofreader’s Parlour, Marcus, and thanks for taking the time to explore the field of genre fiction with us. So to start off, and for the benefit of those who are new to the field and unsure of the terminology, can you tell us what the term “genre fiction” means. Marcus Trower: Thanks for having me, Louise. The border between literary fiction and genre fiction can be a little blurred at times, but basically we’re talking about crime fiction, thrillers, sci-fi, romance, fantasy – that type of book – and the many sub-genres within those genres. Another term for genre fiction is “commercial fiction”. We’re talking plot-driven novels with an emphasis on entertaining the reader. That’s not to say that they can’t deal with big issues. They tend to be books that aren't say, experimental in form, however. These are novels in which, if there’s an unreliable narrator, it’s likely to be in the sense that he or she is someone who can’t be trusted to meet another character at a place and time they've agreed. And should you encounter navel-gazing in a work of genre fiction, it will be during a scene in which a character is admiring the midsection of his or her love interest rather than a passage in which the author, thinly disguised as the narrator, likens his life to a Buñuel film. LH: I’d like to hear more about your specialty areas. Can you tell us a bit about the editing work you’ve completed? Which particular subgenres most excite you from the point of view of an editor, a reader, and a writer? MT: I specialize in working with authors of genre fiction, and within that field, I would say 75 per cent of the total number of books I work on are either mysteries or thrillers, so crime is very much my specialism. The other 25 per cent tends to consist of sci-fi, romance, the odd translation, and the odd zombie story set in medieval England – I’m thinking of The Scourge, by Roberto Calas, which I edited recently. I have a specialism within a specialism, too: mysteries and thrillers with a Spanish language component tend to come my way, since I lived in Spain for a couple of years, and I know my way around the Spanish language. Mysteries have always appealed to me as a reader. I think that’s because I’m fascinated by the idea of hidden patterns and motivations lying beneath the familiar surface of life. Offering my services as a mysteries and thrillers specialist is a natural and sensible thing for me to do, not only because I like reading crime fiction, but also because I’ve been writing my own crime story, a tale set in the underworld of Rio De Janeiro, and I’ve studied the craft of writing crime fiction to an advanced level in order to enhance my own writing. When I started writing the novel a few years back, I made the mistake of thinking that because I’d had a work of narrative non-fiction published, I knew how to string scenes together and tell a story. Fortunately, I soon realized how wrong I was, and I subsequently took crime fiction writing classes to learn about things like POV, building tension, characterization, scene setting, dialogue mechanics, and so on. The courses I took gave me a knowledge base that is incredibly useful to me when it comes to editing the work of other authors writing crime fiction in particular and genre fiction in general. LH: I’ve proofread a fair bit of genre fiction, primarily for publishers, and at that stage my clients are really just looking for that final polish – ironing out any final inconsistencies, layout problems and typos. Editing is a whole different ball game – you’re intervening at a much earlier stage and in a more invasive manner. I do want to explore the challenges of doing this kind of work, and how you manage the working relationship with an author who’s put their heart and soul into their novel, but I think that first it would be helpful to understand a bit about the process. So, when you receive a manuscript, how do you go about it? How do you actually structure this kind of work? MT: I like to read the first couple of chapters without editing or commenting in order to bond with the material. I often make a few notes, jotting down characters’ names and so forth, which will help me later on. During a first read, I’m looking at everything – grammar, syntax, punctuation and style, as well as POV, characterization, scene setting, plot coherence, continuity, verb tense use, dialogue mechanics, possible legal issues, and so on. One moment I might be adjusting hyphenation, the next I might be flagging the fact that an author has forgotten to give a physical description of a key character or querying whether he or she has sought permission to use song lyrics. What I love about copy-editing fiction is how many levels you have to think on. As I said, during that first read, I’m looking to fix or flag absolutely anything and everything that is, or could be, an issue. But I like to keep the forward momentum going during the first read, so if there’s an issue that comes up that requires more than a little thought, I’ll usually flag the passage it comes in and return to it later. Often that’s a wise move, because your perspective on a particular issue can change quite radically the deeper you get into a novel. The first read should remove simple distractions – misspellings, say, or awkward or incorrect style choices – allowing me to see even deeper still into what’s going on in the manuscript during a second read. I spend a lot of time working on comments addressed to the author, making sure that I get the tone right, explain an issue clearly and lay out options effectively. I tend to comment a lot; on average, I write between 150 and 250 comments in the margins of each manuscript – using Microsoft Word’s commenting tool, of course, rather than writing by hand on a hard copy. I know from what publishers and authors tell me that I’m considered to be at the very-thorough end of the editing spectrum, but in my mind I’m actually trying to intervene and comment as little as possible. My aim is to support the author, not impose myself on his or her work in any way, shape or form. When I’m satisfied that I’ve finished going through a novel, I spend a good amount of time reviewing the edits I’ve made, checking that they are correct and consistent, and making any necessary adjustments. I check through all my comments, too, and finish off my editorial letter to the author, which I begin composing during the second pass, and which can run to 2,500 words in length. I like to sit on a manuscript for a couple of days before returning it and the letter, just in case something else occurs to me. LH: You were a journalist in another life, and you’re a published author. This means you edit and you’ve been edited. Is the fact that you’ve been on the other side of the fence, so to speak, a benefit to your editing practice? I feel like I already know the answer to that question, but I’d like to hear your thoughts on it anyway. Is the fact that you’re a writer yourself something you take the time to explain to your clients at the outset? And on the flip side, do you sometimes feel that being an author yourself gets in the way? In other words, can you wear both hats at once or do you feel the need to separate the two at times? MT: Right, I was a journalist for many years. I started off in journalism working for music magazines in the early 1990s – publications such as Record Mirror, Kerrang! briefly, Melody Maker and Vox. I also worked for Time Out and Empire, as well as The Big Issue and Loaded at the beginning of their lives. I subsequently worked for some of the nationals, most notably The Times and a section of The Mail on Sunday that belied the Guardian reader’s stereotypical image of what a publication from the Daily Mail camp is like – in fact, a lot of the journalists I worked alongside there went on to work for The Guardian and The Observer. I freelanced in contract publishing, too, for many years. During all that time, I was always both a writer and an editor. I know what it’s like to be edited well, and I know what it’s like to have what feels like a team of boisterous hippos trample all over my copy. You have to be pretty thick skinned to survive in journalism, though, and there’s not a lot of hand holding. I found that I had to make an adjustment and be a little more delicate and diplomatic when I first started editing fiction than would perhaps be considered necessary in journalism. I don’t go out of my way to mention that I’m a writer to authors, no, but then I don’t hide the fact either, and it’s there in black and white on my website. If I did make a point of mentioning that I’m a writer, that could be a turn-off for authors. They might think I’m going to try to write their book for them, which is one of the worst sins you can commit as an editor. I do stress that I can give feedback on the sort of storytelling elements I’ve already mentioned, though, which does stem from my being a fellow author who’s studied the craft of fiction writing. I never feel like being an author gets in the way – much the opposite. It helps me develop a strong connection with authors and their work. I really, genuinely want to help other writers. To use a terrible cliché, I want to make their book the best it can be. I identify strongly with novelists. I’ve faced the same creative challenges as they have; I’ve faced the same practical ones of trying to find, or buy, the time to write while working a day job. I’ve gone through the difficult process of trying to get an agent, then the even tougher one of trying to get a publisher. I’ve had my fair share of rejection letters and emails. From personal experience, I know how hard trying to make it as an author can be. If I can help other writers by offering them good editing, then that makes me feel good. LH: Getting the author–editor relationship right has got to be crucial, has it not? MT: Yes, it really is. The first thing I do is try to establish a rapport with the author and his or her work. I send out a questionnaire that seeks to find out everything from which other writers out there the author identifies with in terms of style, to how he or she feels about serial commas. The key is to get as good an understanding as possible of what an author is trying to do in his or her work, and to get across right at the beginning that I’m here to help him or her do that. I think it’s very important to set the right tone right at the outset of a book edit in margin comments. On the initial pages, you’re trying to make it clear to the author that he or she is in good hands, you’re not here to mess with his or her style and vision but to enhance the novel, and you’re also trying to establish clearly the principles and reasoning behind certain alterations you’re making so that you can save yourself the trouble of repeating yourself again and again throughout the manuscript. That’s also why it’s a good idea to write a thorough editorial letter. Much of the time I lay out options, since a lot of fiction editing involves making subjective decisions rather than the more objective types of calls you make as a proofreader, say. For example, a comment might begin “You may want to consider . . .” Diplomacy and tact are key. If I spot a dangling participle and a rewrite is in order, I don’t write – and I’m going to exaggerate here – “Honestly, what kind of idiot are you? Do you realize you’ve written a dangler?” but instead something like “There’s a dangler here at the beginning of this sentence . . .”, then quickly move on to laying out a couple of rewrite options, which should prove helpful to the author. You’re there to give constructive help and support. LH: Is editing genre fiction different from editing other types of writing? MT: Obviously there is a lot of crossover with editing other types of writing – there is the same confusion between “it’s” and “its”, or between defining and non-defining relative clauses, say, that you’ll see in all other types of writing. A big difference, though, is that you need to also analyse the storytelling elements I mentioned earlier – POV, scene setting, characterization, etc. Some people would call this big-picture editing, or developmental editing, and not see it as part of the copy editor’s job, but I’ve always offered that kind of feedback and analysis as part of my service, partly because that has been what publishers have asked me to do, and partly because I really do think it is part of the job. If a writer has slipped into omniscient mode while telling a story, but up to that point he or she has been keeping POV discipline and telling the story from the viewpoint of a single character, for example, to my mind that’s just as much a slip as a mistake in grammar or syntax, and it needs to be flagged. There are also style and even punctuation conventions in genre fiction that make it different from other forms of writing. To take an example, in academic writing an ellipsis (…) is used to show the omission of words from a quoted passage, but in genre fiction an ellipsis can be used to indicate that a speaker has paused or trailed off in dialogue, or in narration as a tension-building device – which is something that the crime writer Mark Billingham does, for example. A sentence will begin like this one and be about to reveal some crucial information, and it will . . . have an ellipsis like that one just before the revelation. It’s a little bit like the pause in Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? when a contestant has given his or her final answer, and Chris Tarrant draws out the tension by pausing before revealing whether the answer is correct while that bass-drum music rumbles away in the background. Perhaps, in fact, I should refer to that kind of ellipsis as a Tarrant from now on. Some people might consider it a melodramatic device, but there it is. LH: Newbies reading this will be curious to know how you go about getting work, Marcus. Running your own editorial business in a crowded market can be a tough gig – so how do find your clients or how do they find you? MT: I work quite a lot for CreateSpace’s Thomas & Mercer, 47North, Montlake Romance and AmazonCrossing imprints, which are based in the States. They represent a different side of Amazon’s publishing business from the self-publishing side that everyone’s familiar with. I got work with CreateSpace by taking and passing their editing test. Working for them set me on a trajectory of editing fiction written by US authors, and most of my clients are American. I’m a member of an American organization called the Editorial Freelancers Association, and clients find me through a listing I have on its website. I recently started blogging, and a few authors have found me through my website and blog, too. I don’t really go out to actively find clients, to be honest. Maybe I’m a bit naïve, but my attitude is that if I do good work, people will hear about me and find me, so I focus most of my energies on doing a good job, and I let marketing take care of itself, really. One thing I would say, though, is that in my opinion it’s important to have a specialism, as I have. I think it’s better to come across to authors as a specialist in a particular field than it is to sell yourself as a generalist. I don’t worry about losing opportunities by being a specialist, either. The fact is I do get to work on novels other than crime novels anyway. LH: One of the best things about editorial freelance work is that you can live where you want. Given you live on the Maltese island of Gozo and do a lot of work for the US market, is the fact that you don’t live in the States ever a disadvantage, or doesn’t it matter? MT: Yes, I can live where I want in theory. Great, isn’t it? Thank you, Sir Tim Berners-Lee. If I became complacent and started to believe the Brits and Americans use the same language, I would create a problem for myself. Obviously we do share a language, but there are a lot of differences, as we all know. I’m very conscious of the fact that I’m effectively working in another language, though it’s one I’ve been exposed to from a young age through American TV, films and music, and so on. I’ve had to make some adjustments. I write my editorial letters and comments using American punctuation and spelling rules, and I have to use American grammar and punctuation terms when I communicate with authors. There are many good resources, both online and on my bookshelf, in which I can usually find clarification of specific points that relate to US English and crop up during editing. If I do get stuck – and it doesn’t really happen very often, truth be told – there are always people I know in the States I can run a colloquial expression by to check a preposition used is correct, say. I’ve never really thought about this before, but since the US is such a vast place, maybe a New York-based copy editor has to do the same thing if he or she is working on a manuscript that uses a dialect spoken in the Midwest, for example. Obviously, as a copy editor you amass a big pile of language knowledge, but I think that one of the keys to editing, to paraphrase Donald Rumsfeld, is knowing what you don’t know – and to look up whatever that is. Which I don’t think Rumsfeld went on to say. LH: We’ve primarily talked about your editing; now I’d like to focus on your writing. You post some fabulous articles on your website that are of interest to writers and editors alike. Tell us a bit more about the motivation behind that. And what kinds of things will you be posting about in the future? MT: That’s very kind of you to say. The blog series I write, Be Your Own Copy Editor, aims to help authors, but of course I’m very flattered that fellow editors are reading it, too. Its strapline is “Self-editing advice from the front line of fiction editing”, and that’s the key to the blog for me. It developed because in my work I kept seeing – and still do, of course – the same issues crop up again and again in authors’ manuscripts. I realized that some of these subjects weren't really dealt with properly by grammar books, style manuals and books on writing fiction. There are a lot of resources out there that talk about things such as subject–verb agreement, say, or the difference in meaning between “compliment” and “complement”, but there isn't much guidance about things like when and how to style inner monologue using italics, which I've covered in a blog, or identifying a three-verb compound predicate and punctuating it correctly, another subject I've covered, since compound predicates with three or more verbs are common in genre fiction. I intend to keep posting about issues that are specific to genre fiction but don’t get much coverage, if any, and subjects that are covered elsewhere but which I think need to be both looked at in more depth than they often are and viewed specifically from the perspective of genre fiction. By the way, the series may be called Be Your Own Copy Editor, but I’m not suggesting authors should bypass having their work copy-edited by a professional. My thinking is that the better the shape they get their manuscript in before submitting it to an editor, the more control they have over the final version, and the fewer things there are that can potentially go wrong. I think that’s good for both editors and authors. LH: You also had a non-fiction book published by Ebury Press, The Last Wrestlers, which received some great reviews, and you said you’re writing a crime novel. The two sound a million miles apart! So how did the former come about, and where are you with the latter? MT: They do sound far apart, however a couple of reviewers of my wrestling book were very perceptive in that they described it as being like a crime novel, which I think is true. Like a detective, I was running around the globe – I visited India, Mongolia, Nigeria, Brazil and Australia to do research – trying to discover who had murdered real wrestling and why. The Last Wrestlers grew out of an obsession with wrestling I had during my twenties – with doing it rather than watching it, I should add. I wanted to get to the bottom of why it meant so much to me, and also why it had declined in Britain. I thought, “Hang on. Wrestling is great. It’s a sport with real soul, dignity and history, yet it’s a laughing stock in Britain, where it’s associated with those guys prancing around in spandex on TV. What went wrong?” I spent over two years in the field, as it were, trying to answer that question and other questions.  Courtesy of www.123rf.com Courtesy of www.123rf.com My crime novel is set in the underworld of Rio De Janeiro, a city where I lived for a couple of years, but actually the story sprang partly out of an interview I did with a gunda, the Indian equivalent of a mafia don, while researching my wrestling book in Varanasi. Meeting him affected me a lot. He was young, high caste, physically slight and wore glasses, yet he had personally murdered about eight people, and he controlled elections, politicians and banks in parts of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. In a key opening scene in my crime novel, I transpose certain elements of the meeting to a favela in Rio, and the crime king in my novel is the boss of a fictional drug-dealing crew with similarities to Red Command, which runs a lot of shanty towns in Rio. LH: What was the experience of being published like? Again, we’re back to the point about editing versus being edited – that sense, perhaps, of handing over control to someone else. Did you find the process a comfortable one? Do you hope to go down the publisher route with the crime novel or would you consider, or even prefer, self-publishing? MT: I put my heart and soul into my wrestling book, and the research journey I went on nearly killed me – I mean that in the literal sense. I came back from Nigeria with a very serious tropical disease that the best doctors and professors of tropical medicine in the UK couldn’t diagnose and consequently couldn’t treat properly. Fortunately, I recovered spontaneously. But anyway, the point is that my book was incredibly important to me and told a very personal story, and in some ways I paid a high price to research and write it. So yes, it is difficult to hand over a project like that to someone else. But I was very fortunate in that I had input on the developmental editing level from John Saddler, a brilliant agent who was a creative mentor to me, too, and Hannah MacDonald, then at Ebury Press, who was very perceptive and who I felt really understood where I was coming from as an author. She’s a novelist, too, which of course must help her engage with authors. There were one or two anxious moments, such as when I was told readers were unlikely to be able to stomach a book of over 80,000 words in length from a first-time author, and I’d written over 120,000, I think it was – but I felt like I was in really good hands. And in the event the word count wasn't cut dramatically.  I was fortunate enough to be published very well indeed. Since I lived in Brazil at the time, Random House kindly let me stay at the Random House flat in central London for a few days at the time of the book launch. I was given a PR handler, who took me around various radio studios, where I gave interviews. My book was reviewed in the Telegraph, The Sunday Times, twice by The Times, the Literary Review, The Independent, Arena, and a number of other publications. I did Excess Baggage on Radio 4. The book didn’t then go on to sell in the tens of thousands, though it had respectable sales. In hindsight, I think the title may have been a barrier to finding a readership for the book. Essentially, the book is about being a man in the modern world and it speaks about the topic by talking about my obsession with wrestling; it isn’t a book simply about wrestling. But if you look at the book’s cover and read its title, you probably won’t come away with that impression. I have to say I get a little irritated when authors who identify heavily with the self-publishing and indie publishing boom talk about agents and editors at traditional publishing houses as though they are evil incarnate. I know I had a particularly good experience when my book was published, and not everyone is as fortunate as I was, but a lot of nonsense is talked about the traditional route in publishing. A lot of the people who work in publishing or work as agents are doing it because they genuinely love books, and they love breaking new authors. With my own crime novel, I will try to get an agent for it and then a publisher. I came very close to getting represented by a big agency in London when I submitted it to them about 18 months ago – but a miss is as good as a mile, as they say. My first thought – actually, that’s a lie; it was probably my third thought, and the first two thoughts are unprintable – was that the manuscript just wasn’t good enough to get published, and I needed to work on it further. I hope to produce another draft this year, and if the manuscript gets rejected again, no, I won’t self-publish. I’ll take it as another sign that the novel isn’t good enough and try to improve it. However, I am thinking of revising my wrestling book and producing print-on-demand and eBook versions for sale in the States, partly because I know the book will have some appeal there, and partly because I’d like to go through the process of putting out an eBook and print-on-demand book, because that will help me understand the publishing processes involved, which will in turn help me when I work with authors who are self-publishing using print-on-demand and eBook services. LH: Marcus, thank you so much. The editorial knowledge you've shared is gold dust, both for new entrants to the field and for more experienced editors considering expanding their focus into genre fiction. I've also found the description of your journey as a writer fascinating, particularly given the changes in the publishing market taking place, but also in terms of how you use your experience to enhance the editorial service you provide. And as a keen reader of crime fiction, I'm looking forward to your book! MT: You're very welcome, Louise. It's been great chatting to you. Visit Marcus Trower's blog: Be Your Own Copy Editor. And if you fancy picking up a copy of his book (I'm off to buy a copy now!), it's available on Amazon: The Last Wrestlers. Other posts in the series cover proofreading for trade publishers (Part I; Louise Harnby), editing fiction for independent authors (Part II; Ben Corrigan), and editing adult material (Part III; Louise Bolotin).