|

In this episode of The Editing Podcast, Louise Harnby and Denise Cowle talk to thriller writer Andy Maslen about the creative-writing process.

Listen to find out more about

Here's where you can find out more about Andy Maslen's thrillers. Dig into these related resources

Music Credit ‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

0 Comments

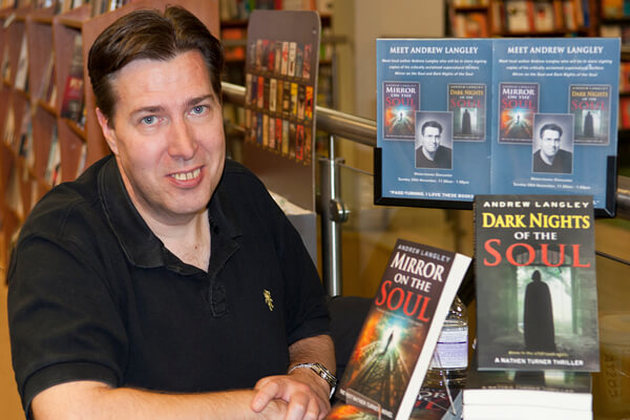

Andrew Langley is the author of the Nathen Turner supernatural thriller series. He kindly agreed to answer some questions about his journey as an independent writer. Below, he talks frankly about marketing, the research and writing processes, and the pros and cons of self-publishing.

This post featured in Joel Friedlander's Carnival of the Indies #82

Hi, Andrew! Thanks so much for talking to me. So what have you found to be the most effective methods of marketing your books?

Thanks for having me! So, for me, the whole point about marketing a novel is profile-building and connecting with an audience, not about hard selling. Someone might write the best book in the history of publishing, but if nobody’s heard about it then nobody will buy it. The most important thing for me at the beginning was to have a website. That way, if anybody asked me about the books, I could give them the web address and they could find out more, and maybe subscribe to the newsletter. It’s more about relationship-building than trying immediately to close a sale. Months before the publication date, I send leaflets to as many bookstores as I can find, just to make them aware of the book. One time, I bumped into a bookshop worker when I was doing a radio interview. She asked me the name of my latest novel. When I told her, she said, ‘Oh, yeah, I’ve heard about that!’ So, basically, the leaflets had done their job. I also think the publication date is important. If it can be tied into some event relevant to the ideas in your story, then it gives you an angle with which to approach the press. My first two books are mysteries based in the world of the supernatural, so I published them on Halloween. I’ve found things like book signings and talks – in fact, anywhere you can meet potential readers face-to-face – much more effective than social media, though they can be a little nerve wracking! I have multiple sclerosis, so when I’m booked for a signing or interview it’s always a bit stressful because I’m wondering what my health will be like on the day. Will I feel fatigued? Am I going to start twitching? What will my pain levels be like? All those issues tend to cloud my mind before the event I’m sure authors without health complications experience nervousness too. Once I'm there, though, it’s great. I’ve found that the public tend to be genuinely interested in authors – why they write, what the book’s about, etc. – and you get to meet some truly lovely people. Another thing that worked well for me was making a load of bookmarks with the web address on. I gave out the bookmarks everywhere I could. The theory was that readers would use them in the novels they were currently reading and they’d have a constant reminder about my books. Have you tested a method of marketing but later shelved it? I’m not the best on social media. By nature, I’m quite a private person, so baring my soul to the world really doesn’t feel comfortable for me. Facebook, Twitter and Goodreads all have their place, and I do think you need to have a presence there to give readers another way of contacting you. But, for me, they don’t really generate sales. Is there anything you’ve not yet tried but would like to in the future? For my third novel in the supernatural series I’m moving the publication date away from Halloween. Although it worked well for the first two in terms of generating press interest, it’s very close to Christmas. The bookstores tend to be focused on seasonal stock and promotions at that time of year. This makes it a real challenge to arrange signings or talks. Thankfully, my local Waterstones has been very accommodating despite the staff workload. So, for the third book, even though it’ll be ready to publish Halloween 2017, I’ve moved the date to Easter 2018. This also ties in to some other events that are relevant to the story. Plus, it’s given me a different idea for a marketing strapline – ‘Relax and read a book for Easter (but keep the lights on!)'. That kind of thing!

Do you have a method or process when writing?

I live off notebooks! Everywhere I go I carry a notebook and jot down ideas. I was a photojournalist for a long time and I got used to this method of working when I was on location. Sometimes I’ll overhear a funny story in a bar and think it’ll be great to add that to a novel in the future – it all goes in the notebook for recycling later. All my background research goes into the notebooks and I handwrite the synopsis and first chapter long before I sit in front of a computer. Then I usually test the story idea with my friends and family. If they’re not immediately interested, I change it until they are. Once I have the bones of the story, I create a storyboard from beginning to end that covers the key scenes, and I write some dialogue as well to get a sense of how the characters feel in these. Once all this is done, I finally sit in front of the computer. As I already have a clear idea of the story and the characters, I try to write a chapter per day. At this stage, I don’t worry about perfect grammar or even a single nuance – I just want to get the story down from start to finish and see whether it works. I write every day for as long as it takes until I’ve nailed that chapter. It can mean very long hours. The following day, I read through what I’ve done and then start the next chapter. Once I’ve got the book finished, I put it away for a few weeks. The second pass is when I fine-tune the grammar, and make sure I’ve added in all the scents, sounds, feelings and nuances that bring the story to life. At this point I’ll let a few friends or family members read it so I can get their feedback. Then I revise the manuscript again. I might repeat this process many times before I send the file to a professional editor for review. How much research do you do for your novels, and how do you go about it? Researching a story takes me many months, even years. I always write about what I know or have experienced in some way or another. So I’ll visit the locations in the story if at all possible, take photographs, talk to the locals and get a feel for the location I’m writing about. In my photojournalist days, I travelled a lot and kept notes, so in some cases I can rely on those. My main character’s base in the supernatural series is Whitby, on the east coast. This is a town I’ve been visiting since early childhood and I still go there with my family. I love the place. The second book is set mainly in the Scottish Highlands. My father was Scottish and, again, it’s a place I know well from both work and leisure. I do other research by trawling the internet, reading relevant books or interviewing people who know about the subjects I’m writing about. I try really hard to make things as authentic as possible even though I’m writing about things like ghosts and witchcraft in the first three books. The fourth book, which I’m working on now, is a historical adventure based on the legacy of the Jacobite rebellion of 1745. For the past six months I’ve been back and forth to Scotland, checking out the locations, talking to people, visiting museums and so on. I’m hoping to finish this research by August; then I’ll write the story.

Where do you get the inspiration for your stories?

The idea behind the supernatural series came from a conversation about psychic mediums. There’d been some news claims about a famous psychic using devious methods to gather information that they’d then used in their shows to wow the public. Whether this story was true or not I don’t know, but it gave me an idea. What if there was a psychic who knew he was a fake but whose heart was in the right place? So he didn’t believe in any afterlife or spiritual world but could fake it because he believed he was doing the right thing – bringing comfort and closure to the bereaved. Now, what if this person then unwittingly summoned a very real ghost in one of his sessions, and this ghost was intent on wreaking revenge? The basic idea struck me as funny and something people might enjoy reading about. Hence, Nathen Turner, my psychic medium character, was born. The idea behind the adventure I’m writing now came after I stumbled across a news story about the Jacobites. I can’t say too much about this one at the moment but I’ll put information about it on the website or my Goodreads blog once I’m further into the process! Have you ever suffered from writer’s block? If so, how did you get through it? A very weird thing happens when I’m stumbling over my writing – the characters seem to come alive and tell me what they’d do! I know this sounds bizarre but the characters are real people in my head. Many times, I’ve wondered where to go in a scene but written it anyway. Then I’ve read it back and thought: This person wouldn’t behave like that. So I change it. I think that the more you work with your characters the more this tends to happen. Sometimes I look back and can’t even remember writing a particular scene – it's like I’ve had a stream of consciousness and become so wrapped up in the story that I’ve put it down without thinking too deeply about it. Occasionally, I’ll end up pacing around the garden or heading for a strong caffeine fix if I can’t figure out the best way to get the words on paper. Having the bones of the story already mapped out in my notebooks is a huge help here. I go back to them and make sure that what I’m writing stays true to the original idea. Is writing a series an important part of your strategy? Personally, I think that writing a series is vital for an independent author. The more books you have out there in a series the more visible you become to readers. Also, people who like one book will usually buy the others in the series. Hence your sales increase without any expensive promotional activity. When I wrote the first book I already had the basic stories for the other two in my head, as they were part of my main character’s development – he gets more and more involved in the supernatural and the legacy of his past. I’ve planned out other stories for this character already but I’m taking a break from him to write an adventure story. Again, the characters in this new adventure can build into a series, and I have a rough idea of how I could make that work. How have you found the experience of self-publishing? Self-publishing has been a huge learning curve. I was used to a press background where you do a story and it gets in the press or on TV the next day. Fiction publishing is simply not like that. Writing a novel is a slow process involving many revisions long before it gets anywhere near a professional editor or proofreader. Even after that, there’s the time it takes to typeset and come up with a cover design you hope will appeal to readers. And then there’s Nielsen, Ingram Spark, CreateSpace and so on, and learning how their systems work. So, yes, a huge learning curve. Luckily, there’s a lot of information on the internet to guide you. The biggest nail-biter is after you’ve sent the finished novel off for independent review and you’re waiting to see if the reviewers like it. This is a story you’ve poured your heart and soul into for a long time. If your work gets pulled apart it’s a bit like someone criticising your children. I was very worried about that! I’ve been very fortunate so far – the books have been well received. It’s a huge boost to your ego but there’s always something in the back of your mind that’s waiting for that first bad review. At the end of the day, it’s impossible to please everybody, but I always hope that if the novel has been through the various editing steps, then most of the flaws have been ironed out before it faces the public. The biggest benefit is control over your own destiny and the sheer pleasure of writing. The downside, as ever, is financial. Without a publishing contract behind you, you’re taking all the risks and have to pay for all your promotion. And you don’t know whether it’ll pay off. My attitude is simply that I have to make it work somehow. With my health condition, there are very few options left to me workwise, and desperation can be a great motivator!

Do you have any tips for new writers who are considering self-publishing?

For anyone considering self-publishing I’d say give it a go. It’s a fascinating world that has revolutionized the publishing industry. There are two general approaches I’ve seen other writers take. The first is to study what’s currently in the bestseller market and write something that will appeal to the same readership. As I don’t want to write about kinky sex scenes or zombie apocalypses, I didn’t choose that approach but there’s nothing wrong with it. The second method is to have an idea that might work within a specific genre that you know about and enjoy reading. This is the approach I took as I felt my writing would be much more genuine and true to myself, and my readers. Once you’ve decided on an approach, I suggest studying what’s out there. What do the covers look like? Which titles appeal to you? How can you create something new? How will you build a brand identity for your own work? I spent a very long time on this before I created a look for my novels that was true to myself and fitted my genre. After that, there’s the interior design. Which styles do you like and how could you make your work indistinguishable from a mainstream publisher’s? I think readers expect a certain quality in their print and ebooks – after all, they’re paying good money for them. I chose a font and style that I liked and then tested it on family and friends to see what they thought. Getting feedback is, I think, vital. An independent publisher will be investing hundreds of hours in their project so it’s important to have the right mindset from the start or all that time will be wasted. Once you’ve got the finished article, I recommend giving away some signed free copies to people you know socially who run local reading groups, bookstores and organisations. Really, it’s just about letting people know you’re an author, and if you’ve done a good job with the cover and the typesetting, they’ll definitely take you seriously. Anything you wish you’d known before you wrote your first book, and that you’d do differently now? At the beginning, I was obsessed with getting an agent and a publishing contract. I didn’t know at the time how many submissions the agents receive and that the chances of securing representation for the genre I write in are between slim and none. I also didn’t know that the majority of mainstream published books are not a commercial success and that many sell less than 750 copies even with a heavy-hitting publisher’s backing and advertising. If I’d known that, I think I’d have gone straight into self-publishing without a second thought and not bothered submitting to agents at the beginning. The other thing I found out is that, because of their workload, only 30–40% of the agents get back to you, and your submission might even be overlooked by mistake. So it can be disheartening. Sometimes it just means that your book doesn’t fit their current needs. I don’t think it’s worth getting too worked up about. Many self-published authors can make a success of their work – it just needs perseverance and more relationship building than hard sell, in my opinion. Anything else you want to mention, Andrew? I think the best advice I could give anyone who wants to be an author is simply to write. Stick to a schedule and do a daily stint. Don’t worry about coining the perfect phrase. After it’s down on paper, you can alter and correct as much as you like. A first draft is exactly that – the basic story in the raw, if you like. Add in weather, smells, sensations etc. to make your imaginary world believable, to bring it alive. Background research is key for me, and it’s wonderful to discover new places and experiences. Keep a notebook and write down everything that you come across. It might not go in your current work; instead, think of it as a treasure trove for the future. Most of all, enjoy it! I love writing and creating new stories. I’m a lot less mobile than I used to be. Creating my new adventures on paper has been more than a lifeline – it’s been an adventure in itself, and one I thoroughly enjoy! You can find out more about Andrew and his novels on his website: www.andrewlangley.co.uk

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

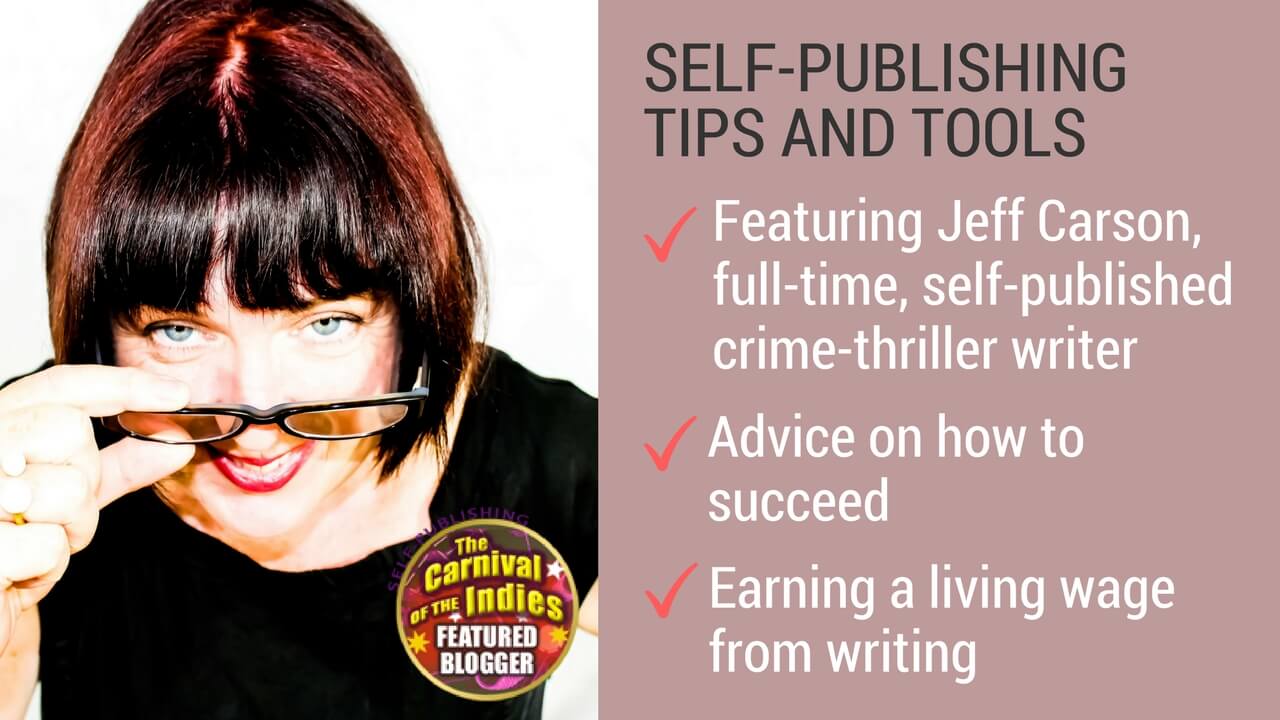

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. FIND OUT MORE > Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader > Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn > Learn: Books and courses > Discover: Resources for authors and editors How to make a living from self-publishing fiction This week's post is a cracker. Self-published author Jeff Carson has kindly agreed to discuss his writing journey.

This post featured in Joel Friedlander's Carnival of the Indies #81

Jeff's a mystery and thriller writer from Colorado. Writing is his full-time job and he makes a living from his self-published series.

That's a dream for millions of independent authors; below, Jeff shares 11 tips on how he turned that dream into a reality. If you're at the start of your self-publishing adventure, this is definitely for you!

My name is Jeff Carson and I’m the author of a series starring David Wolf, a cop living in the fictional town of Rocky Points in the Colorado Rockies. Right now, I’ve written ten books in the series.

When I first started out writing, I remember being tormented at night by questions swimming in my head (and by mosquitos … at the time, we were in Italy for a year, and they were thick that summer, I tell you). Questions like: Can I really do this? Can I make a living at it? Is this just a waste of my time? What if everyone hates the books?

By finding a few people online who’d made a success of becoming a self-published author, I was able to get a lot of my questions answered and some inspiration that propelled me towards making a living as a fiction writer. I despise playing the guru, and I’m cringing a little as I write this, but I have accomplished the goals I laid out five years ago. So I have to say that I feel l’ve succeeded in the self-publishing realm. There are others, many others, who would scoff at my level of accomplishment, but this blog post isn’t for them. This is for those who are in the position I once was, in that sweat-soaked Italian bed. Here are 11 things that have helped me succeed as a self-published author. 1. I want to make a living doing this That’s been the over-arching goal from the beginning. I wanted my paycheck to come from writing. I wanted to make money twenty-four hours per day from people reading my books. I’ve met many people who approach writing as a therapeutic tool for their lives. That’s fine. But 100% of people who write get the therapeutic benefit. One only makes money from it if it’s a goal. You don't wake up with a horse one day by random accident. There’s a lot of intention and action that goes into suddenly having a hay-eating animal roaming around in the back yard. Same thing goes with earning a living from writing. 2. I wrote a book series I learned that if you want to make money from writing fiction, the odds of success go up dramatically by writing a series. Since my goal was to make money with this gig, naturally I wrote a series. Harlan Coben is the exception, not the norm. On this note, I learned the hard way to not leave books ending on a cliff-hanger. I'd done this with book one and received a lot of negative reviews. I’ve since fixed the novel so that all story goals are resolved and it ends completely. In my series, my characters grow and their lives change from each book to the next, but I try to make each book a stand-alone. This helps with marketing, too, since anyone can pick up one of the David Wolf novels at any point in the series and feel grounded and up to speed. 3. I over-estimated, or realistically estimated, the level of work it would take to achieve my goal (of making a living writing) I knew that one book in a series, the first book I’d ever written and published in my entire life, would make no money. Pessimistic? It’s not. First, I was learning how to write a story. Second, I wasn’t expecting to gain a wide audience with a single book taking up a single slot in the vast Amazon universe. I knew book one was the hook – the mouth of a funnel – that would lead to the rest of the books in the series. In fact, I knew I was probably going to offer the first book for free. I needed multiple books in multiple categories grabbing people’s attention, all of them leading readers to the other books sitting in other categories. The series would act as a big net. I figured that after three books I’d be making some ‘extra money’. I hoped that after five I’d be making enough money to quit all other work and concentrate on writing only. Then I doubled that number. Therefore, I created a goal of writing ten books; then I’d judge the venture one way or another. In reality, after five books I was able to write full-time and make a full-time living wage. Now that I’m on book eleven, my goals, expectations, and earnings have elevated.

At the beginning, I felt that if I set my work expectations too low, I’d become discouraged, and fast. Because if after, say, four books I was still irrelevant and making nothing, then my hopes would be dashed.

Some people would call a ten-book ‘realistic expectation’ pessimistic, but in my mind it’s the reason I kept going when, after three books, I’d known months that wouldn’t have paid for a week’s worth of groceries. 4. I concentrate on what I want every day I’ve filled two college-ruled notebooks with lists of my goals. Every day (or most days) I open up a notebook, list the writing goals/life goals with specific deadlines, such as when I’ll finish the first draft and when I’ll publish, and then I get to work. I learned this technique by reading this Brian Tracy book on goal-setting: Goals! How to Get Everything You Want – Faster Than You Ever Thought Possible. That book definitely changed my life. I'd never even had goals before reading that book. Now I always set goals. Deadlines always get pushed back, which would be depressing if I let myself to think about it. But the system doesn’t allow for that. Each day is a new sheet, and a new list of goals with either the same deadlines or adjusted deadlines. Looking back on previous lists of goals is not permitted. 5. I read the bad reviews This is a biggie. I’ve heard some authors say, ‘I just ignore the bad reviews.’ I adopted that stance for quite a while, actually. But there’s always something to learn from a bad review. In fact, I think it’s dangerous and irresponsible if you ignore the one- and two-star shellacking some people take pride in giving out between hangover-induced trips to the bathroom, the sons of bitches. Some people get specific – ‘Nice try. A Sig Sauer P226 doesn’t have a safety! Amateur writer at best. I will not be reading another piece of filth by this author.’ So, fine. You skim past the amateur comment and go fix the book so that the special agent DOESN’T flick off the safety as she steps out of her SUV. I think my books are orders of magnitude better because of the bad reviews. I figure that if somebody came up to me on the street, pointed, laughed, and criticized my outfit, I’d shake my head and move on, not in the least worried about that person a few steps later. But if her criticism is, ‘Your fly’s down … oh, yeah, and your pants are on backwards. Idiot,’ well, then, I want to know that. 6. Screw it. I don’t need social media Early on, I adopted the stance that I needed to write my way into relevance as a writer, not tweet, post, or whatever my way into it. Once I adopted this mindset, a weight lifted off my back. I hated it for some reason. I couldn’t get a grasp on social media, so I just let go of it. My investigation leading up to my decision showed a correlation between how much an author published books and how successful they were, between how many positive reviews a book had and how successful it was. I could check an author’s success by looking at the rankings of their books on Amazon and other market places. There was no correlation, however, between how present people were on social media and their book rankings. In fact, more often than not, I saw that people who were successful had all but abandoned their social media accounts. In contrast, there were people all over Twitter and Facebook, with hundreds of thousands of friends/followers, and books lost in obscurity. Clearly there are exceptions, and some people have great success with social media, but my reasoning was: you write your way into being a writer. I rarely post on Facebook, and when I do, it’s usually a link to my new books – classic poor social media behavior. Screw it. I don’t care.

7. I am accessible

I respond to every communication sent to me. I think this is huge as a writer, or as a person in general. Nothing irks me more than somebody simply not responding to something. The most surprising thing about writing, and that I sometimes get all teary-eyed about, is the amount of love people will send your way after they’ve read your novel. People will click on the email address (which I put in the back of the book) and contact me, telling me how much they like my book. For me to not say thanks is plain psycho. Plus, it’s just good business. People who like you are more likely to share the news about your work. 8. I have a newsletter email list This is one of those things I heard people preaching – you have to have an email list of readers – but never did anything about. It took me four freaking books to finally put my email list in place. But I finally did, and that’s when I was finally able to write full time. It only took two days to write and publish a short story, which I give away on my blog as a thank-you if somebody signs up for the new-release newsletter. Now, when I have a new release, I launch the book to thousands of people, versus dropping it into a field of crickets. 9. I write in sprints first, edit later This is one of those huge game-changers for me. I was getting upset sitting in front of the computer every day but only coming out with one or two thousand words. Now, I write in sprints, which means I write in thirty-minute blocks, take a five-minute break, and then do it again. Using the backspace button is not allowed (a rule I break all the time … my OCD won’t allow David Wolf’s name to be Wols for more than a few seconds). It took me six or so books to employ the sprint tactic, and now I’ll never write any other way. 10. I have a self-editing PLAN After tapping out a real crappy draft of a terrible book, then going back through a few times, editing, ironing out inconsistencies, tightening up descriptions of dead bodies, etc., I have in the past simply read and re-read the book, then tweaked until I felt it was ‘as good as I can get it’. I’m ashamed to say, it’s only been recently that I’ve implemented a self-editing plan. The plan is something like …

11. I hire an editor who does it for a living, for a rate that allows her to do it for a living After seven books, going through three editors, and becoming frustrated with the service I was getting, I realized that I needed to hire an editor who was an editor and only an editor, and who charged a rate that clearly allowed her to feel properly compensated. The alternative is hiring somebody who does the work on the side for cheap. They’re pressed for time. They’re secretly (I imagine, because I would be) pissed off about being underpaid for a job that deserves more money. The equation adds up to a poor editing job on the finished product … suspicious stretches of pages – five, ten at a time – without a single mark on them. The saying goes, ‘You get what you pay for,’ and it can get tricky when paying for editing services. For years, I tried to get away with paying less. And I definitely got less. ... In today’s publishing environment, I know that, for me, every bit of advice helps. I hope at least one of the tips above helps you on your journey to becoming a successful self-published writer.

Where to find Jeff and his books

Louise Harnby is a fiction copyeditor and proofreader. She curates The Proofreader's Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. If you're an author, you might like to visit Louise’s Writing Library to access my latest self-publishing resources, all of which are free and available instantly. How lucrative are your editorial clients really? Keeping an eye on creeping costs (Part II)9/3/2015

We need to take care when making assumptions about how lucrative certain client types are, particularly with regard to the time each of us spends on elements of the process that are unbillable. Here's part 1.

In this two-parter, I consider the care we need to take when making assumptions about how lucrative certain client types are, particularly with regard to the time each of us spends on elements of the process that are unbillable.

These unbillable elements can occur during the booking phase of a project, during the actual project work, and after completion of the work. Part I considered the problems of defining how well clients pay and how fee expectations can vary even within, as well as between, client types. Then I looked at the booking phase of proofreading work, and considered how the situation can vary between a regular publisher client and a new non-publisher client. Part II considers how additional costs can creep into the actual editorial stage of a booked-in proofreading project, and into the post-completion phase – again comparing regular publisher clients and new non-publisher clients. It’s worth reiterating the point made in Part I: Not all of the scenarios considered here will always occur with each client type on each job. Rather, I aim to show that (a) extra costs are less likely to creep in with the regular publisher client, and (b) this needs to be accounted for when considering which types of client are ‘well-paying.’ Creeping costs during the editorial stage Here’s a fictitious, but likely scenario. Let’s put to one side any costs incurred to firm up the job at booking stage. Regular publisher client, PC, offers me the opportunity to proofread a 61,000-word fiction book for £17 per hour. The client estimates that the job will take 15 hours. Total fee: £255. Also in my inbox is a request from a self-publishing author, SP, with whom I’ve not worked before. It’s also a 61,000-word fiction book. I assess the sample of the manuscript that’s been provided (it’s in good shape and has been professionally edited). I estimate the job will take 15 hours, and quote a fee of £345, which is accepted. The job for SP looks much more lucrative on paper than the job for PC. I accept both jobs because even though the job from PC will bring in a lower fee, it’s still within my own particular required hourly rate. I do the PC job first. I’ve worked for this publisher for years. We have a mutually understood set of expectations about what is required. The manuscript has been thoroughly copy-edited and professionally typeset. As usual, I receive a clear brief and a basic style sheet. It’s a straightforward job that takes me 15 hours (the in-house project manager is experienced enough that he can estimate with accuracy how long a job should take). I complete the work and return the proofs along with my invoice. End of job. Next I tackle the SP book. It is in good shape and I should be able to complete the proofread in the time I estimated. However, I’ve underestimated the amount of hand-holding required. This client is a lovely person, but she’s a first-time author and she’s nervous. She sends me 13 emails during the course of the project, each of which takes time to read, consider, and respond to. I keep track of the time I spend on these. On average, each one takes 15 minutes to deal with – that’s an extra 3.25 hours of my time that I’d not budgeted for when I quoted for her. It’s also an additional 3.25 hours of my time that I have to find space in my day for. I have to find the time out of office hours in order to respond – time that I’d rather spend doing other things. The quoted fee was £345, based on 15 hours of work. This has turned into 18.25 hours of work. My hourly rate has gone from an expected £23 (cf. £17 from the publisher) to £18.90. It’s still within my required hourly rate, but my assessment that SP is more lucrative than PC is disappearing under my nose. Of course, I should have quoted her a higher fee that took account of the fact that she was an unknown entity to me and that the job might take longer. Again, it’s essential to consider the bigger picture when assessing the degree to which a particular client or client group ‘pays well.’ With some clients, it’s harder to predict how a project will progress. And with non-publisher clients, especially those with whom there’s no preexisting relationship, it’s essential to build hand-holding time into the assessment of how long a job will take, and then quoting accordingly, so that you’re less likely to get caught out. Creeping costs after completion of the project I’ve been proofreading for publishers since 2005 and in that time the post-project correspondence has tended to go something like this: Me: Thanks for the opportunity to proofread X for you – I really enjoyed it. Please find attached my invoice and my Notes & Queries sheet. Delivery of the proofs is scheduled for Y. If there’s anything else I can help you with, please let me know. PM: Cheers, Louise. Glad you enjoyed it! Are you free to proofread…? That’s the general gist of our post-project discussion – it’s friendly but concise. We’re already talking about forthcoming work. This recent job is closed. My PM’s schedule is as tight as mine and we’re both keen to move on. This isn’t always the case when we proofread directly for non-publisher clients. The following snippets of post-project emails from clients are fictitious but I’ve encountered the like many a time. Do they strike a chord with you?

It’s not unusual for these post-project discussions to take place. What is less usual is that editorial professionals manage them appropriately. Too often, they become unbillable costs that detract from the project fee. There’s nothing wrong with a client asking these things and it’s not that the editorial business owner shouldn’t have these conversations. They do incur a cost, though. If you regularly build post-project handholding time into your original quotation, all well and good. But if you don’t and you are prone to offering free, additional support to your clients, take a step back and ask yourself how much this is impacting on the value of each project, and your required and desired rates. If you spend an additional two hours emailing back and forth about these extras, that time needs to be set off against the invoiced fee; those hours need to be tracked so that you can work out exactly what the final value of the project is to you. A better solution is to communicate to the client, immediately and politely, that you’d be happy to discuss X or Y, and what the cost will be for the additional work. I appreciate that for some editorial folk this is very difficult because they’ve built up a strong relationship with the client during the editorial process, and the tone of communication may well have become informal, even friendly. However, we have to remember that we’re running a business and that our professional expertise has a fee attached to it. There’s no shame in putting a price on the additional work we’re being asked to carry out. Controlling creeping costs Here are some thoughts on how to keep control of creeping costs in editorial work:

By being aware of ALL of the time we spend on a project with our clients, we can develop insights into the financial health of our business. This enables us to make decisions about who we want to work with and what their actual value is to us. A quick summary: 5 things to remember when assessing client groups

A version of this article was first published on An American Editor.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Independent author T.P. Archie recently published A Guide to First Contact, a post-apocalyptic novel set in 2060.

His search for editorial assistance initially led him to me. However, after some discussion about what was needed, we agreed that he’d benefit from an developmental and line editor, not a proofreader. I pointed him in the right direction and he hired one of my SfEP colleagues to work on the manuscript. Now he’s been kind enough to take time out of his busy schedule to talk to the Parlour about this experience, and his independent publishing journey more broadly.

Parlour: First of all, congratulations on publishing your book! Can you give us a short synopsis of the novel and tell us how the idea for Guide came about?

T.P. Archie: Hi. Thanks for inviting me in. Guide alternates between the present day and a post-apocalyptic Earth. On the edge of the solar system, Star Beings plan the next phase of their work. New life. An animite must be hurled onto the third planet. The impact will scatter organic compounds throughout Earth’s biosphere. But there’s a problem: the animite goes missing. A hundred thousand years later, it’s the 21st century. A space mission to a near-earth object makes an amazing biological discovery which is brought back to Earth. This American secret is trumped when France announces contact with creatures from outer space. Then disaster strikes. Technologies in key industries begin to fail. The West collapses … It’s now 2060. Most cities are long abandoned. All that remains of the once-mighty United States is the Petits États, centred on New England. Outside of there, civilisation survives in Enclaves, relying on the confederation of Sioux Nations for protection. For forty years a genetic plague has ravaged humanity. It began just after Earth was contacted by aliens. A new and mysterious power – the mandat culturel – controls access to advanced technologies.

Triste, hopeless with girls, but good with guns, is a bounty hunter. He has all the latest ordnance. His contracts pay well but are dangerous. They take him to the ruined cities; he spends a lot of time in the former urban area of New York.

His current mission is to reconnoitre a long lost laboratory. He encounters a ramshackle band of opportunists whom he sends packing. In doing so, he meets Shoe. They find the lab. It has secrets linking it to the collapse of Western civilisation. Shoe is running from her family. She has other secrets. In the dead shell of Manhattan lurks a secret pensitela base. Their alien biology protects them from the brutal savagery of the place. They have their own reasons for being there. From the edges of the solar system, a Star Being monitors Earth. It has a plan – and Triste meeting Shoe isn’t accidental. His troubles have just begun. Eventually he is faced by the hard truths behind the fall of the West.

At its most basic, Guide is a series of interlinked narratives that combine to reveal how the apocalypse comes about. Other readings are possible. One of my objectives was to explore different kinds of first contact.

However, Guide didn’t start like that. It began as a test of Novel Writing Software – yes, there’s a product really called that! I planned to write three chapters, which I thought would be sufficient for my purpose. So out it churned, an endless stream of 'hero takes on hordes from hell'. At about 8,000 words I took stock. I already knew it wasn’t intellectually satisfying yet I had found a writing rhythm. It occurred to me that while I was in my stride, I should experiment. Why didn’t I add something with a bit of interest? I had a few characters kicking around in my head. "Everyone has a novel in them," I told myself; all I needed was a theme to link them together. In they went; and the violence was trimmed. That was it; I was hooked. I wrote and added themes. There’s gender reversal – the story won’t work properly without it – and Darwin’s theory of evolution (these two are linked). Then the never-ending Anglo-French rivalry; followed by a drip feed of classical Greek philosophy. Each theme had a purpose. Why? I want SF that makes sense, including the cosmogony. Depicting aliens, for example, requires some attention to how they might see the universe. In retrospect, I realise I’d grown away from SF/Fantasy; little of what was available appealed to me. I was sitting around waiting for someone to write the stuff I wanted, which wasn’t happening. Parlour: Could you tell us a bit more about yourself and how you started writing? T.P. Archie: I qualified as an accountant in 1990. My mother was born to a family of Estonian farmers and my father began life as a cobbler. I grew up in a one-parent family. Most of my early life was lived in Stoneyholme, a deprived part of Burnley. My mother rented from a block of terraced houses. There was plenty self-inflicted misery, but it was rarely safe to observe. As the son of an immigrant with a German accent, it was my duty to avoid the occasional beatings that were due to me. Grammar school education informed me that the oppressive reality of working-class life stopped at the edge of the estate. I began reading SF/Fantasy in my teens. This was later complemented by an interest in classical philosophy and history. Once I started writing, I found a great deal to say. Parlour: Who are your biggest influences (from a literary point of view)? T.P. Archie: My formative years were very much influenced by genre authors, e.g. Asimov, Clarke and Heinlein. I continue to be impressed by Tolkien’s myth building and the universe of Frank Herbert’s Dune. Outside the genre I have found Dostoyevsky, Kafka, Pasternak, George Eliot and Doris Lessing to my taste. I am also partial to Plato and the works of Idries Shah. My writing is also influenced by the work of Orson Welles. (Oh, okay – he didn’t really write :) ) By the way, I’m ridiculously pleased with my Philip K. Dick collection, tatty Ace editions and all. Dick is best known for Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, which inspired Bladerunner. Dick didn't need to spell out apocalypse, yet his settings work. His characters think a great mix of the mundane and the profound. Seemingly omnipotent creatures are driven by biology or freely admit their fallibility, as Glimmung does in Galactic Pot-Healer. Many of his works are laced with dark humour and are worth a reread. Parlour: Like many other authors around the world, you've decided to go down the independent publishing route. Self-publishing requires the wearing of many hats in addition to the writing. What have been the upsides and the downsides of this decision? T.P. Archie: Upsides: you control everything. Downsides: you control everything. Okay, that was tongue-in-cheek. The main benefit is that you are in control over the pace of your development. Once you have a deal, you are locked into it. As an indie author, I don’t feel the constraint of writing to fit genre style/house style. Ask the right questions at author events and the strictures of formulaic writing become clear. I've read widely in my chosen genre, including many of its standards. There are many themes to explore/treat differently. The most significant drawback was in the narrative – devising a practical approach to self-editing. While shaping ideas, I’d revisit text. If words didn’t come, I’d use "next best", i.e. placeholder terms, and work it until it was there or thereabouts. This resulted in intermittent problem areas. Sometimes I attempted to clean these up but this was a chore. I’d ask of myself, "What comes through in the narrative? Does it need reshaping?" I was too close to answer that, and a long way from feedback. I moved on. In my heart of hearts, I knew there were better approaches but I lacked the comfort of funds, so investigation wasn't an option. Besides, it was still a hobby. Did I plan to go DIY? I saw no choice. New authors produce first novels. First novels are best kept locked away in a drawer, hoping no one reads them; or (in my case) kept for practice. Many new authors go on to sell a few copies to friends and families. It’s a hobby and a fine one. You learn how to put a PDF together; you Photoshop-up a half-way reasonable cover – and if that doesn't appeal there’s plenty of stock imagery out there. Then you get to make friends with local book-sellers and libraries. Soon your edition has gone from sales of 10 units to say 100 and you can get stuck into decisions such as how many to print (economic order quantity for the business inclined). That’s a long road which begins with up front financial commitment, a dry garage and benign family arrangements. So, back to me – before I spent, how ready was I? How much confidence had I in my book? What was acceptable quality? What did I do to reach that bar? These are big, big questions which each author must decide for themselves. Anecdotal evidence suggests that a high proportion of self-published product doesn't make the grade. The follow on question to this, kind of asks itself: Am I self-critical enough? The only way is feedback. Parlour: So tell us about that. What was your experience regarding feedback? T.P. Archie: Completing that first draft gave me a tremendous burst of energy. There was so much more to write. What did I do? Jump the gun or wait? There were troublesome areas but I was too close to it to deal properly with them myself. I needed feedback and had none. So I seeded drafts to those who thought they might like to read it through, and I waited. I hoped that this would put me in a better position to know if it was worth writing more. It was only hobby time, but I might as well get it right. I waited for feedback ... and waited. It was a long time coming. That time was frustrating, to put it mildly. While I waited, I reacquainted myself with the rudiments of grammar and punctuation. I joined writing groups and reluctantly practised short stories. There’s nothing like reading out loud for finding flaws in your work. Finally I got feedback from my draft. It became clear that I needed to reshape Guide. I realised there was still a long way to go and I had to up my game. The stage points of that journey weren't yet clear. I continue to practise short stories, which, contrary to my initial opinion, gave significant benefit. Parlour: How long did it take to get Guide from the conception stage to the marketplace? I ask because some of the conversations I have with more inexperienced indie writers leave me worrying that they might not be being realistic about the length of time the process takes. T.P. Archie: A quick answer is four years. Could I have done it quicker? No. Longer answer: At the time, I thought I would be finished with the process in six months. Having said that, it’s worth pointing out that my original objective wasn't writing per se. In fact, it didn't matter if I couldn't write; my objective was to test a software package. It was only when I’d "done enough" for that initial purpose (my target was 8k words) that I realised I had something to say. Basically, I was a committed hobbyist who got sucked in. My early view changed from "let’s do 8k words" to "I bet I can finish this off in 60k words". I gave myself three months to get to first draft (it took three and a half) and a further three to tidy things up. This latter goal was totally unrealistic – it assumed a level of proficiency in editing my work that I didn't possess. The three months for first draft misled me because the effort, although considerable, was compacted together. Much longer was needed to give Guide a finished gloss. How long would I allow now? It would make me uncomfortable to imagine I could do it in less than a year. At the moment I’d calculate the minimum time as:

Why all that extra time? There’s little chance that Guide could have been ready earlier than it was. I wanted to get things right. While I waited for feedback there were things I could do that wouldn't be a waste of time. First things first: a test of commitment, learn the ropes. I learned Lulu (POD/ Print on Demand), dabbled with Photoshop, put work into devising blurb, table of contents, copyright, permission to quote. The drip of feedback began. I got stuck into editing. The more I did, the bigger Guide got. It started at 60k words and grew to 80k. Then I received good-quality feedback. A complete rethink was required. I needed to convince myself that there was mileage in the next step. Plusses and minuses two years after first draft would have read:

With hindsight, I now know that my product wasn't ready; I needed to develop as an author. What wasn't clear was how much time was required to become half-way competent. Much of the past four years has been spent looking for feedback and dealing with it. I've a better idea how much work goes into publishing. Using other expertise means you spend more time in your comfort zone. I've spent a lot of time in business, enough to know that I've little interest in activity that adds little value. Successful authors should prioritise and focus on what they’re good at: writing. During this time the stages I went through were:

Parlour: Some independent authors take a completely do-it-yourself approach to the self-publishing process – including the cover design, editing and proofreading. Why did you decide to hire an editorial professional, how did you go about the task, and what qualities were you looking for? T.P. Archie: By 2012 I’d done all I could, Guide could progress further. I rested it. A change of circumstances made that extra investment possible. Browsing on Goodreads gave me the idea that it needed other eyes, and that proofreading might be worth looking into. I ranked proofreaders; you came top. Hiring an editor was a leap in the dark. I’d little idea of how to proceed so I went with gut instinct. Stephen Cashmore became Guide’s editor. Parlour: What were the biggest benefits of hiring an editor? T.P. Archie: It smoothed out my style and helped me understand what worked and what didn't. This has given me confidence in my other projects. Parlour: Any challenges? T.P. Archie: Definitely. The main one was to disengage thoroughly from the story design in mind – i.e. what I meant to convey – and actually deal with the editorial comment. I flip-flopped on some changes; in others, what I thought I needed to do didn't work. At times I needed to check my original intent; fortunately, my notes plus backups were up to the task. I found the editing process to be very helpful. Parlour: If you could do it all over again, would you do anything differently? T.P. Archie: Interesting question. As far as the actual writing goes, things fell out as they did. The main characters had been in my head for some years. I felt little urge to write something I could get over the counter; the piece was always going to become complex. The decisions affecting the outcome couldn't be envisaged until after first draft. Some were merely opportunities, which if not pressed would have held me back – e.g. I pushed for the local writing group to reform, even though I knew little of writing and less of those who would come to make up that group. Selecting an editor was an act of faith but there was a real choice. I wasn't entirely sure how things would progress. Different outcomes were possible – but given a rewind, I’d be unlikely to do anything differently. I still have more to learn. Parlour: Many of this blog’s readers are editors and proofreaders. Is there any advice you’d like to offer to us about dealing with independent authors so that we can do our very best for you? I currently publish a set of Guidelines for New Authors, and, like many other editorial professionals, I'm keen to ensure I offer indie writers the information that’s most helpful to them. So what should we be doing and what might we do better? T.P. Archie: Many potential clients don’t have a literary background and so won’t understand the value of your services. I think it’s worth taking me as an example ... In 2012, Guide had progressed as far as I could take it, yet I was certain that its story was worth extra effort to get it into the marketplace. However, what to do wasn't clear. I had little idea what could be achieved and I put it on one side. I came across the SfEP by accident, while following up a comment made on Goodreads by a US proofreading business. I ran a web search, ranked the results, emailed the top ranking proofreader who helped me find an editor. Encountering you (and hence the SfEP) wasn't a guaranteed outcome. It takes courage for first time indie author to let a professional look at his work. The edit began. Issues were identified and ranked into major/moderate/minor. Changes were proposed. I prioritised my effort. Nearly all the minor changes were accepted without question. Suggestions for other issues were helpful and I followed many of them. Guide had several types of problem. The story structure required a rethink, the style was inconsistent, and the text was too fragmented. In many places, the pace of the plot was let down by the narrative. The benefits from the edit were significant. I put Guide into chronological order. Style excesses and inconsistencies were smoothed out. Fragmented text was joined up. I dealt with problems on a case-by-case basis. Some solutions came from my editor; dialogue translation was provided for the one chapter where Russian is spoken. This added authenticity without detracting from the pace. In another case a solution evolved in the to and fro of the edit – a lengthy dialogue was demoted to the appendices, where it actually plays better. The overall result is more readable. The edit kept me in my comfort zone and solved a major headache; knowing how much to edit, and when to stop, was now solved. I had a better idea of what worked and what didn't. In addition I got an idea of where the boundaries of taste lay (where Guide strays near the edge, it is for story purposes). The whole thing has given me a great deal of confidence; I now know thorny problem areas can be identified and improved. I'm certain my editor would agree with me if I said I was slow on the uptake. For this, and other reasons, what editors and proofreaders do needs to be out there and spelt out. A book on this sounds a good idea. [Editorial freelancers] are more likely to find value from those who are already seeking out their services. Parlour: Having now achieved that final goal of getting your novel to market, what advice would you give to any indie author who’s considering self-publishing? T.P. Archie: Self-publishing requires an author to get a lot of things right. Some of these are tasks with steep learning curves that can take an author away from his/her comfort zone. New authors need to make judgements on where their expertise stops. Where the processes are mechanical (e.g. POD formatting) it is clear if you have this right or not. As far as the actual writing goes, you are too close to your work to make that call. Any indie author seriously considering first-time publication would do well to consider putting it through copy-editing. I plan to do this with my next novel. In the case of Guide some kind of final check was needed. Proofreading seemed a good idea; it actually needed copy-editing. That process was well worthwhile. Parlour: What does the future hold? Do you have plans for future novels, and, if so, will they be in the science fiction genre? T.P. Archie: I have four genre pieces in progress. In 2012, I dared to look forward, on the heroic assumption that Guide could be finished; I asked myself “What I would like to write next?” The ideas I liked were:

I've made starts on each of these. There are also a number of themes coming out of Guide that I would find interesting to follow up. Before that happens I’ll do a little marketing. I'm on Goodreads, where I'm planning a "giveaway". I also want to tell local newspapers about Guide. There’s a press release, some bookstores to visit and, in between, I might read a few extracts onto YouTube. I promised to inform Octagon Press, agents to the written works of Idries Shah, as well as the Department of Public Affairs at Mayo Clinics ... Parlour: Thank you so much, T.P. I think independent authors and editors/proofreaders can all learn a huge amount from the experiences you've so generously shared!

To buy A Guide to First Contact, visit Amazon or Lulu:

You can contact T.P. Archie as follows:

Louise Harnby is a fiction copyeditor and proofreader. She curates The Proofreader's Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn. If you're an author, you might like to visit Louise’s Writing Library to access my latest self-publishing resources, all of which are free and available instantly. In this interview, I talk to author Michael K Rose. I love hearing about the the joys and challenges of being a self-publisher, the new technologies and procedures indie authors are using, and how they manage the process of being both publisher and writer. I'm a massive a science-fiction fan so when, in 2011, a Twitter pal posted something about Michael's work, I took note and started reading. I wasn't disappointed. The thing I love about Michael's stories is that they stray well beyond the boundaries of what some might consider to be traditional sci-fi; his readers are as likely find themselves exploring the inner space of the mind as the outer reaches of space. This interview was conducted in 2012, at which stage he'd published a collection of short stories, and one novel, with a second in revision stage. Since then, that book's been published, and he's added another 11 to the stable! Louise Harnby: First of all, Michael, can you tell us a little bit about yourself and your writing? Have you always focused on science fiction, broadly speaking? What’s the appeal of this genre for you? Michael K Rose: I've always enjoyed the broad genre known as speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, etc.) but sci-fi has, for me, been a life-long love, whether it be in the form of films, television shows or books. Some of my earliest writings were science fiction, and while I have dabbled in other genres (and have several non-science fiction projects in the works) I believe that the majority of my work as a writer will be science fiction. LH: I read The Vast Expanse Beyond: 10 Short Stories a few months ago and absolutely loved it. I’m already a fan of both the short-story format and the sci-fi genre, but what really stood out for me with this collection was how it managed to surprise as well as entertain me – I didn't always know where the boundaries were between sci-fi and psychology. Is that something you particularly like to play with in your writing? MKR: I'm so glad you enjoyed it! I don't always know where a story is going to take me, especially when writing short stories (for my novel-length works I have a clearer idea, and I do outline, but nothing is off the table even then). I love all types of science fiction (hard, soft, over easy) but, as others have stated, science fiction is ultimately about people. And people experience things psychologically, emotionally, not just physically. Placing a story in a science-fictional setting with all its wonderful technology and meticulous world-building should not be an excuse to neglect this aspect of story-telling. We, as readers, don't always know the state of mind of the characters. Even if the story-teller (me, in this case) indicates one thing, there is no way of knowing if I'm even being honest with you. Straight story-telling is fine, and for the most part that is what you'll get in my novel Sullivan's War, but when it comes to short stories I tend to try different things. It's how I can play without wasting a month's worth of work if it doesn't turn out. I will mention that the sequel to Sullivan's War, Sullivan's Wrath, does play a lot more with psychology and characters' states of mind. LH: One of the stories in the collection, "Sergeant Riley’s Account", is a prologue the Sullivan’s War series. How did that come about? Was it harder to write with a pre-existing story line in your head, or did it help you flesh out the first novel in full? MKR: "Sergeant Riley's Account" was written long before the idea for Sullivan's War emerged. I also had most of a novel called Chrysopteron written, but I didn't feel as though it was close to being ready for public consumption. So for my first novel-length project, I decided that I wanted something action-oriented, something that would be fun to write but that still had some depth. "Sergeant Riley's Account" gave me the universe in which to set Sullivan's War as well as the narrative style that I wanted to use. I also had a couple of short stories that made their way into Sullivan's War, and that helped flesh out the novel quite a bit.  Photo: Michael K Rose Photo: Michael K Rose Are there other short stories to which you might return in the future because you have more to say? In “Inner Life”, for example, I felt that devilish itch a reader sometimes gets with a great short story to explore the protagonist’s world just a little more! MKR: Thank you! Your saying that means that I accomplished what I set out to accomplish. If a reader is left wanting more, s/he is likely to seek out more work by the author. I don't plan on revisiting any of the characters in The Vast Expanse Beyond but it's not outside the realm of possibility. Right now I'm writing twelve novels in twelve months [see below] so short stories are, for the moment, on the back burner. But I love writing (and reading) them, so there will definitely be another collection at some point in the future. LH: Can you tell us a little about your editing process, Michael? Do you use proofreaders or copy-editors to put the final polish on your work before it gets published? If so, what does the process involve for you in terms of finding the right person for the job and communicating your expectations to them? Do you have any concerns about this element of the process? MKR: I actually don't use an editor or proofreader at this time. When I first began self-publishing, I had everyone and their dog telling me I needed an editor. Some even went so far as to say that any book published without an editor would, essentially, suck. I began by e-publishing a few short stories. I wasn't too concerned about it at that time. But when I put together my first print book, my collection The Vast Expanse Beyond, I knew that any errors could not be easily fixed once it went to press. So I did the work that needed to be done. I'm blessed (and cursed) with a rather meticulous mind and I tend to notice errors in just about every book I read. I also spent not a little time researching grammar, punctuation, etc. Can I edit as well as a professional whose spent years doing the work? No. Of course not. Can I self-edit to the point where the vast majority of readers will not notice an occasional missing comma? Yes. And for me, the difference between my work before being looked at by an editor and after being looked at does not justify the expense. I do have friends who beta read for me and they also help me find some errors, but by the time my work is ready to be published I have personally gone through it at least half a dozen times (including re-reading during the writing and revision process). And the work has paid off. Several people have complimented me on the professional appearance of my books. But I do not recommend self-editing for most authors. However, if an author does decide to self-edit, I would strongly recommend taking the time to brush up on grammar and punctuation. When I did so I discovered that I held many erroneous assumptions about proper usage. LH: Earlier, you mentioned the #12NovelsIn12Months writing project. You prepared a Q&A in anticipation of the questions you thought you’d be asked. The first was, “Are you insane?” I’m not going to repeat that here because such an ambitious project clearly deserves closer scrutiny. Would you talk us through it? MKR: Right now, my circumstances allow me to write full-time. That may not always be the case, so I have decided that for the next year I will write a full novel each month. As I wrote on my blog, I have a dream to make a living solely from my writing. If I don't pursue that dream now and do everything I possibly can to make it happen, the opportunity may not come again. I do not want to wake up one morning ten years from now and realize that I let my dream slip through my fingers. I will fight for it. Even if it does not come to pass, I can resign knowing that I did everything that was in my power to make it happen. Producing twelve full novels over the next year is, quite literally, everything I can do. LH: To date, you've self-published. It’s exciting to see talented writers taking this particular journey and, in the process, bending the traditional rules of publishing. I imagine you've put a lot of hard work into not only the writing but also the digitization and marketing of your books. Have these elements of the publishing process come easily to you or have there been challenges along the way, too? MKR: Of course there have been challenges. I spent countless hours playing with html formatting and researching how to create particular effects to make my ebooks as professional as possible. Writing a story and letting Amazon's (or some other entity's) software convert it into an ebook for you is easy. But that ebook is probably not going to look the way you want it to look. I also learned how to use photo-editing software to create book covers, which prior to self-publishing I had only toyed with. I began developing my social media presence, making connections with other authors, starting a speculative fiction webzine, giving interviews. This is on top of the work I did honing my grammatical skills so I could properly edit my work. Oh, and there was a little bit of writing in with all that, too. It has been an incredible amount of work and anyone who wishes to self-publish must know that if you want to be successful at it (and I do consider my results so far a success) then you have to either spend the money to have someone do all the things I've talked about or else take the time to learn how to do them and do them well. LH: Would you ever go down the traditional publishing route, now that you've mastered the art of doing it yourself? Would you feel that you’d lose some degree of control or would you welcome this as another avenue of opportunity? MKR: If the terms were agreeable, I would of course consider "trad" publishing. But I am very proud of what I have accomplished as an Indie writer and will always support Indie writers when I can. LH: You probably get asked all the time to give advice on how to go about publishing your own novel, so I’m going to throw the question on its head and ask you what your top three “Don’ts” are. MKR: Hmmm ... 1) Don't go in with any expectations with regards to sales or reception. The only thing you can control is your book, not how people will respond to it. If you are happy with what you have done and know that you have given it your all, that is a success, even if you never sell more than a hundred copies. 2) Don't go it alone. Even before you begin to think about self-publishing, start making connections with other self-published authors. I was overwhelmed by the kindness and generosity I found in the Indie community and have done what I can to help other authors who have sought out my advice. There are people out there to help you. Don't be afraid to ask, but don't be upset if they decline. Most Indie writers must write in addition to holding a day job, raising children, etc. Ask for advice but don't ask too much of others unless you've developed a strong relationship with them. 3) I'll quote Henry James: "Three things in human life are important: the first is to be kind; the second is to be kind; and the third is to be kind." You never know who your next biggest fan/supporter will be. Avoid divisive discussions about politics, religion, etc. Treat others with respect. Don't make negative comments about other writers. If you act like a professional, people will treat you like a professional. LH: And finally, what plans do you have for the future, Michael? Anything in the pipeline that you’d like to share with us? Yes, I want to know about Chrysopteron! Can you give us a little teaser of what we can expect? MKR: Chrysopteron is the next novel that will be published. It is currently under revision and I hope to have it out by Christmas. This is the blurb that appeared in the back of The Vast Expanse Beyond: "Five generation ships were sent from Earth in the hopes of colonizing distant planets. The Chrysopteron was one of them. In a tale that examines issues of faith and self-determination, Michael K. Rose explores just what it is that makes us human. Will we ever be able to engage those who are different from us with love and understanding, or is the human race destined to forever be divided by trivial concerns? Even though we may leave the Earth, we cannot leave behind that which makes us human." I am sure the blurb will undergo several revisions between now and publication but hopefully that will have whet readers' appetites. I've lived with the characters in Chrysopteron for about three years now and they are very real to me. I am taking my time with it because I owe it to them to get this one right. Thank you so much for the interview! LH: Thank you, Michael. The glimpse you've given us of how you go about writing, editing and publishing is fascinating and inspiring. I appreciate your taking the time to share it. Michael K Rose is a science fiction, fantasy and paranormal author. His first major work, Sullivan’s War, has been called “… a sci-fi thriller that definitely delivers!” His second novel, Chrysopteron, has been hailed as a “… gem of a novel…” and “a masterpiece.” Michael holds a bachelor’s degree in Anthropology from Arizona State University. He currently resides in the Phoenix area and enjoys board games, tabletop role-playing games and classical music. For more information, please visit his official website or his blog Myriad Spheres. You can also connect with him on Twitter or Facebook. Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers. She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

In this interview, Jo Bottrill talks about life in the busy project management agency Out of House Publishing.

Louise Harnby: Thanks for agreeing to talk to the Parlour, Jo. First of all, can you tell us a bit about yourself and how you got into the publishing business?