|

Want to increase your productivity? My guest Simon Raybould has an innovative approach to organizing your work day that might just cut you some slack and help you get more done. Over to Simon ...

We’ve all done it … worked our little socks off only to feel like we’re banging our heads against a brick wall.

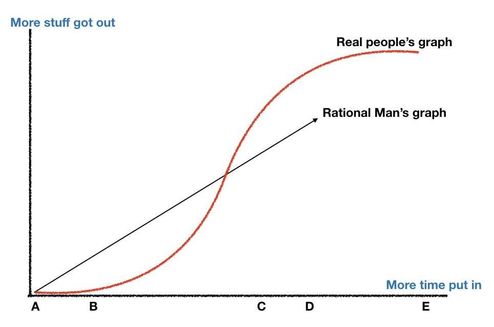

I know a few editors and proofreaders, and there’s always more for them to do – either doing the job itself or marketing the job so that there is a job to be done. I assume you’re like them, so I won’t try to convince you that you’re working too hard, and that, by definition, ‘good enough’ is exactly that. Despite the logic of that statement it falls on deaf ears too often to be worth it. I’m going to pick my fights! So instead of looking at how long we should work on something in total, I’m talking about how long we should work on it in any one go. Rational Man Economists (and some others) use a concept called Rational Man. Let’s call him Fred. Fred knows everything he needs to know to make an optimal choice for every decision, and – being rational – makes it. In other words, Fred gets perfect choices each time there’s a choice to be made. If you’re Fred, there’s a perfectly straight and positive relationship between how much effort you put into something and how much output you get out:

It couldn’t be simpler, could it? But it’s not real. You know that. Imagine sitting down at your desk and being productive from the first second. Unlikely. How life really is If you’re anything like me, when you sit down to work, the first few minutes of your time don’t create any output. Instead you:

Okay, so you might not be as bad as that, but you take my point. I’ve labeled this in the graph as the time between A and B.

But once you get going, warm up, well then you really hit your stride. Each minute produces not only output but more output than the previous one. In the graph, this is the time between B and C.

Eventually, of course, you start to get tired. You’re still getting things done but each minute achieves a little less than its predecessor, until you’re barely getting anything more done for each moment. In the graph, this is the time between C and D. Here’s the rub though… most of us are conditioned to just work, work, work, work, work, and we carry on doing so until:

Let’s be blunt – most of us work on towards E. The last time I talked about this in a workshop I was greeted by a chorus of ‘E? More like the whole damned alphabet!’ We do this out of habit because we’ve never stopped to think about it. However, I’m hoping it’s pretty obvious from that graph that common sense suggests locating the point at which we should stop if we want to be most productive. When it’s pointed out to them like this, most people point to somewhere around D and say that’s where to stop. (Mathematically it’s C, but D is close enough.) The point is, it’s got to be before E, obviously. But it’s only obvious when you step back from the grindstone and look at it like this. How long is your A–D? Ah, now… that’s the question. It’s different for different people, and for different tasks for the same person. For example, I start to lose the will to live after about 15 minutes of proofreading. After about 20 I lose the will for anyone within reach to live, too. You have been warned. By comparison, I have a member of my team (hello, Clare!) who can smell a misplaced comma in the dark, before I turn on the computer on, and at a range of over 200 miles. For proofreading, her A–D is about 90 minutes. Conversely, when it comes to research I can work solidly for up to two and a half hours or so. (I spent 24 years as a university researcher.)

How should we use this?

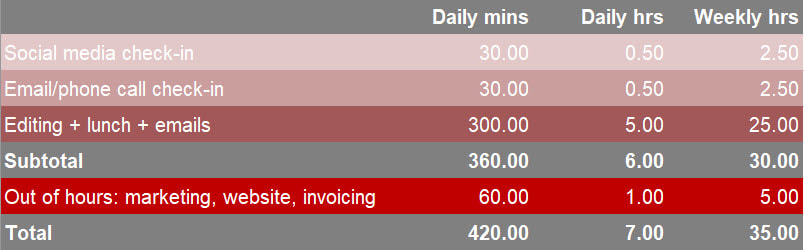

Here’s a simple tool that will help you be as mind-bendingly productive as possible. Jot down all the major things in your job – ignore stuff you only ever do once in a blue moon. And be quite crude about it if you need to. Then make your best guess of your A–D for that time. I asked Louise, our host, to put together some numbers. These are crude estimates but they give you an idea.

Remember, these are Louise’s first guesses for how long she can undertake each task until she becomes tired and unproductive, not how long she should work on any given document/book or whatever. When you know how long you’re at maximum productivity for, block those things into your diary in time chunks that match, less about 20 minutes or so (use some common sense here for things with only a short A–D!). Lots of people find it handy to set up an alert on their phone for the t−20 moment; when it goes off, you should ask yourself a brutally hard question – formally, consciously and with intent: Am I in the C bit of the graph or past it? If things are good, you’re golden. If not, adjust the time in your diary and the alert on your phone. Use the new information in the future. Back to Louise. This is what her typical working day looks like at the moment. Note that she’s only got six hours in a day, so straight away you can see that something’s got to give!

That way she’s be working at her maximum productivity for much more of the time.

Wouldn’t it be lovely if by upping how much work she can cover in a six-hour day, she doesn’t need to steal time from her husband in the evening? (Your mileage may vary of course! You might want to have the excuse!) The downside What’s the snag? Well, the main drawback of this is that your diary will look like an explosion in a rainbow factory and you’ll have to put some effort in to make it work. Nothing worth doing works without a bit of initial mental sweat. Implementing this change might require a complete shift in your mindset. And for that you’re gonna need a whole lot of chutzpah. But trust me – it’s worth it. You spend units of ‘courage’ and get back units of time. Personal note (or bragging, if you prefer) Still not convinced? By making sure I chopped my day up to what worked best for me, a couple of years ago, in only a three-month period I achieved the following:

You may have detected a degree of smugness there. Sorry! Your turn! What do you think? How long are your A–C periods? And your C–E periods? The ratio between those two could give you a reasonable idea of how much time you’re wasting. Let us know!

Want to know more?

Simon's a presentations expert as well as a productivity guru. If you want to get in touch, here's what you need:

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

3 Comments

Nancy

25/9/2018 03:10:19 pm

This is something I want to try. I remember reading an article about the productivity of the poet Wordsworth and others like him. They were so productive precisely because they only worked about 4 hours a day.

Reply

Louise Harnby

25/9/2018 08:21:33 pm

Let me know how you get on, Nancy!

Reply

17/12/2018 01:00:45 pm

Hi Nancy - sorry for the delay! The trick is to look busy enough the rest of the time to keep your boss happy! ;)

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

BLOG ALERTSIf you'd like me to email you when a new blog post is available, sign up for blog alerts!

TESTIMONIALSDare Rogers'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'Jeff Carson'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'J B Turner'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'Ayshe Gemedzhy'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'Salt Publishing'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'CATEGORIES

All

ARCHIVES

July 2024

|

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed