|

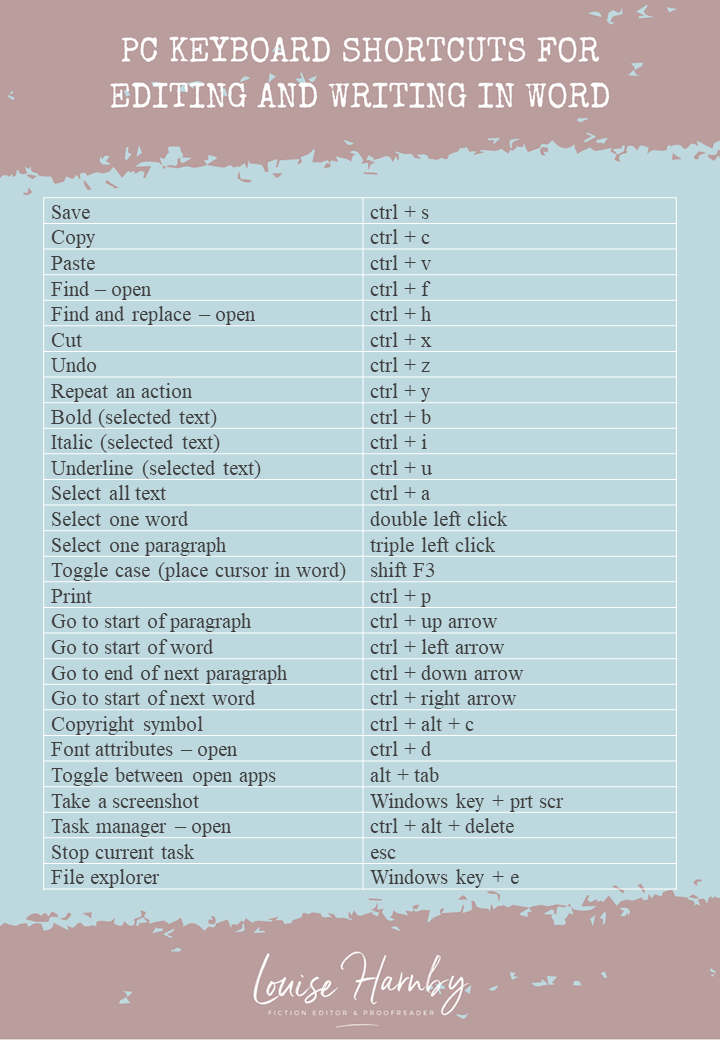

Writing or editing in Microsoft Word on a PC? Save yourself time by learning these 27 keyboard shortcuts.

If you don’t want to learn 27, learn just the first one: Save!

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

5 Comments

Are your readers bouncing from one character’s head to another in the same scene? You might be head-hopping. This article shows you how to spot it in your fiction writing, understand its impact, and fix it.

Rebus pushed open the wrought-iron gate. No sound from its hinges, the garden to either side of the flagstone path well tended. Two bins – one landfill, one garden waste – had already been placed on the pavement outside. None of the neighbours had got round to it yet. Rebus rang the doorbell and waited. The door was eventually opened by a man the same age as him, though he looked half a decade younger. Bill Rawlston had kept himself trim since retirement, and the eyes behind the half-moon spectacles retained their keen intelligence.

‘John Rebus,’ he said, a sombre look on his face as he studied Rebus from top to toe. ‘Have you heard?’ Rawlston’s mouth twitched. ‘Of course I have. But nobody’s saying it’s him yet.’ ‘Only a matter of time.’ ‘Aye, I suppose so.’ Rawlston gave a sigh and stepped back into the hall. ‘You better come in then. Tea or something that bit stronger?’ […] ‘Sugar?’ Rawlston asked. ‘I can’t remember.’ ‘Just milk, thanks.’ Not that Rebus was planning on drinking the tea; he was awash with the stuff after his trip to Leith. But the making of the drinks had given him time to size up Bill Rawlston. And Rawlston, too, he knew, would have been using the time to do some thinking. Anaylsis: Tight third-person limited narration Rebus is the viewpoint character. That means the internal experiences we access are limited to his. For example:

We cannot get in Rawlston’s head. All we can do is consider his internal experiences via his observable and audible behaviour, and his dialogue. For example:

What head-hopping would look like Here’s what that excerpt might look like if there was head-hopping going on:

Rebus pushed open the wrought-iron gate. No sound from its hinges, the garden to either side of the flagstone path well tended. Two bins – one landfill, one garden waste – had already been placed on the pavement outside. None of the neighbours had got round to it yet. Rebus rang the doorbell and waited.

Bill Rawlston walked down the hall and peered through the peephole. Rebus. Same age as him, though he looked half a decade older. He opened the door. Rawlston had kept himself trim since retirement, and the eyes behind the half-moon spectacles retained their keen intelligence. ‘John Rebus,’ he said, a knot forming in his stomach as he studied Rebus from top to toe. ‘Have you heard?’ The question riled him. Was Rebus stupid? ‘Of course I have. But nobody’s saying it’s him yet.’ ‘Only a matter of time.’ ‘Aye, I suppose so.’ Rawlston begrudged letting Rebus in but stepped back into the hall. ‘You better come in then. Tea or something that bit stronger?’ […] ‘Sugar?’ Rawlston asked. ‘I can’t remember.’ ‘Just milk, thanks.’ Not that Rebus was planning on drinking the tea; he was awash with the stuff after his trip to Leith. But the making of the drinks had given him time to size up Bill Rawlston. Rawlston had used the time to do some thinking, too. Rebus turning up here after all those years – it pissed him off. Analysis: Confused narration Notice how we bounce between the heads of Rebus and Rawlston. Now we have access to the internal experiences of both.

In that butchered version, the reader is forced to play a game of ping-pong on the page. Why head-hopping spoils fiction Here are 4 reasons to hold viewpoint rather than head-hopping:

1. Head-hopping renders a story less immersive

In Rankin’s original prose, we are limited to the world of the novel as Rebus experiences it. That’s powerful because every word on the page is a step we take with Rebus, as Rebus. I get to be a male, Scottish detective for a few hours rather than a female, English book editor! In my butchered version, I take that first step with Rebus but then trip and fall into Rawlston. Because I’m bouncing between those characters’ internal experiences, I don’t have time to invest in either. And so I stay as lil’ ol’ me. I do like being me, but when I buy one of Rankin’s books I want to immerse myself in its world for a few hours at a time and dig deep under the skin of the viewpoint character. I can be me without paying fifteen quid for the privilege!

2. Head-hopping diminishes suspense

In the original text, Rankin keeps the suspense tight by allowing us to access only Rebus’s senses. Rawlston’s sombre expression, twitching mouth and curt responses make Rebus (and us) think, Does he want me here? Does he begrudge my presence? What’s going on in his head? Those questions demand answers and we seek them in the clues offered by the limited narrative. Because the limited viewpoint requires Rebus and the reader to make assumptions based on what’s observable and audible, there’s uncertainty. That’s what provides the suspense, and it compels us to keep reading in the hope that the truth will be unveiled. In my head-hopping version, the prose is flat. There are no questions. We know what everyone’s thinking because we’re in everyone’s head. Readers aren’t called upon to use their imagination – both characters’ internal experiences are spoon-fed to us.

3. Head-hopping is less authentic

Head-hopping reminds readers that they are in a story written by an author. We don’t get to suspend belief because the writing won’t allow us to immerse ourselves that deeply. In Rankin’s original prose, we walk through the world as if we are Rebus, and Rebus alone. That’s what happens in real life. I know only what I’m thinking, feeling, seeing and hearing. I can’t be sure than another’s perception is the same. Audio-visual signals help me make reasonable assumptions but I’m only ever in my own head … or Rebus’s if I’m reading a story about him because Rankin knows how to hold viewpoint. In my mangled version of the excerpt, there’s a reality flop. Now I’m everyone, which is ridiculous of course. Authenticity has fallen off a cliff.

4. Head-hopping can be confusing

When a writer head-hops, the reader has to keep track of whose thoughts and emotions are being experienced. When a reader doesn’t know where they are in a novel for even a few seconds, that’s a literary misfire. This is what happens in the head-hopping excerpt. For example, Rawlston walks down the hall and identifies Rebus through the peephole. We’re right with him, in his head. But what follows is jarring. That he reports on his spectacles sitting in front of keenly intelligent eyes is oddly self-aware. Of course, it’s not Rawlston’s perception; it’s Rebus’s. And once we realize that, the prose makes sense. But working that out is not where Rankin wants the reader’s attention. He’s telling us a story and he wants us to read it. That’s why he holds a tight limited viewpoint throughout. Head-hop check Make a list of the characters in a chapter or scene. Identify the viewpoint character. There can be more than one viewpoint character in a book but most commercial fiction authors separate them by chapters or sections. Here’s a quick way to check whether you’re holding viewpoint. Viewpoint characters: What the reader can access

Non-viewpoint characters: What the reader can access

Some examples to show you the way

Summing up Even if your readers don’t know what head-hopping is, by removing it from your novel you’ll give them a more immersive, suspenseful and authentic journey through the world you’ve built. Plus, you’ll ensure they’re reading your story, not trying to work out who’s telling it.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with independent authors of commercial fiction, particularly crime, thriller and mystery writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast. Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses. The impact of ‘before’ and ‘after’ in fiction writing: Tacit and explicit chronology of action17/2/2020

When the order of characters’ movements is told with the words ‘before’ and ‘after’, there’s a risk that readers will focus on timeline rather than story. That distraction can reduce engagement and dumb down the writing.

Here’s what to look out for and how to fix the problem.

In this article, we’ll look at tacit and explicit chronologies of action, and assess which style of writing is more immersive and why.

Why writers include ‘before’ and ‘after’ The inclusion of ‘before’ and ‘after’ to tell the order of play is not an indication of poor grammar – not at all. There’s nothing grammatically wrong with these constructions.

More usually, it’s an indication of insecurity. The author hasn’t learned to trust the power of their words on the page, or the ability of their readers to perceive the meaning behind those words.

It’s also why writers sometimes use several adjectives with similar meanings rather than one strong one, or an adverbial phrase to fortify a weak verb. Some authors also fear that their writing will come across as too ‘plain’ or ‘simple’. Chronological nudges are an attempt to ornament the prose. Tacit chronology of action The things that we do occur in a sequence; they have a chronology. This is as much the case in real life as it is on the screen, in an audiobook and in the pages of a novel. That chronology is tacit – we don’t need to explain it because it’s understood. Take a look at this excerpt from The Devil’s Dice by Roz Watkins (p. 79, HQ, 2019): Watkins doesn’t tell us explicitly that the shuddering occurred before the laptop was put down, or that the laptop was moved before the character shifted the cat onto their knee. And yet we know. The sequence of events is implied by the order in which she places each clause. It’s tacit.

And that’s the thing with strong line craft – it allows the reader to immerse themselves in the chronology of action by showing us, clause by clause, what’s transpiring, instead of tapping us on the shoulder and telling us. Explicit chronology of action Let’s recast the Watkins excerpt with some explicit taps on the shoulder:

I shuddered before putting the laptop down, then manoeuvred Hamlet onto my knee. After leaning in, I breathed in his subtle, nutty cat smell.

I see this use of timeline nudges frequently in the fiction writing of less experienced authors, and it’s problematic when overused. Here’s why. 1. Some readers might feel patronized Not every reader will notice the use of chronology nudges. But some will, and since no author wants to alienate a chunk of their readership, why push the story over a cliff when we can work out the sequence of events from the order of the words? Telling readers that X was done before doing Y, or after doing Z, is akin to saying: ‘Hey, just in case you’re not clever enough, let me spell it out for you.’ It’s a dumbing-down that readers in the know won’t appreciate. 2. The inclusion is unnecessary If you’re still not convinced, ask yourself whether the inclusion of ‘before’ or ‘after’ as timeline nudges is necessary. It often isn’t. If a character’s shuddering occurs at the beginning of a sentence, the reader will assume that shuddering is what’s happening right now. If a new action follows that shuddering, the reader will assume that – just like in real life – the moment has passed and something else is happening in the new now of the novel. 3. The reader is focused on the wrong thing When writers create immersive fiction, the reader feels as if they are in the moment – this is happening, now that, now the other. ‘Before’ and ‘after’ are distractions that focus the reader on when rather than what’s happening. The former is telling; the latter is showing. 4. There are more words than are necessary Not enough words leaves readers hungry for clarity. Too many gives them indigestion. The artistry comes in the form of balance. As long as the sequence of events can be understood by the reader, consider whether timeline nudges such as ‘before’ and ‘after’ are cluttering your prose.

The power of tacit chronology – more examples

Take a look at these pairs of narrative text, each of which has a shown tacit chronology and an alternative told explicit sequence. Which versions are more suspenseful? Which are most immediate? Which flow better when you read them out loud? I’ve used examples from published fiction for the tacit versions, and taken a little artistic licence – altering them in ways their authors never intended – for the explicit chronologies. In the original version, the ‘and’ between the initial breath and the walk into the kitchen is a fine example of the power of a conjunction. It’s almost invisible, which gives us the space to take that breath with the viewpoint character. And having taken it, we’re ready to go into the kitchen with them. In the edited version, ‘before’ pulls us away from that moment. The tension has fallen out of the sentence.

In the original version, it’s as if we’re in the room, watching the man as he smiles and leans back. There is space for that action to have its moment. Then he blows the smoke – that’s the new moment; we’ve left the other behind. In the edited version, ‘after’ shoves us past the leaning back and smiling before we’ve had a chance to savour it. It’s already gone, even though we’re still reading about it.

In the original version, Crichton shows us the action. Perhaps, like me, you can hear the chunter of the helicopter blades in the air. Who’s in this helicopter? Men in uniform. They jump out. What will happen next? We’re shown: they fling open the door. There’s a sense of order, of clandestine and militaristic precision. In the edited version, ‘before’ saps the suspense from the final sentence. We’re focused on the timeline rather than the action. Summing up The table below summarizes the impact of tacit and explicit chronology on prose.

Take a look at your narrative. If ‘before’ and ‘after’ are telling rather than showing, recast gently and reread out loud. Is the order of play still clear? Is the prose more immersive? If so, there’ll be fewer words but what’s there will be all the richer.

And if you’re worried that your prose will be too plain, think again. Immersive writing allows the reader to decorate the story with their own imagination.

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Flat chapter finales are a fast track to reader disappointment. Here’s how to nail those last few lines so that readers can’t wait to turn the page.

Readers turn the page to find answers to questions. Why did that happen? Who’s responsible? What will happen next?

Unanswered questions at the end of chapters place us in a state of suspense. We’ll try to predict the answers based on the information we’ve been given. We might be proved right. I thought so! We might be proved wrong. I didn’t see that coming! Either way, as long as there’s suspense, we’ll turn the page. Here are some ideas, with examples from published fiction, about how to do it, so that even predictable outcomes are structured line by line such that readers are itching with anticipation. 1. Wrap up the chapter in the middle of something interesting There are two people in a bedroom. They’ve survived a harrowing encounter. And there’s oodles of sexual tension between them. A less confident writer might wrap up the chapter as follows:

‘I’m sorry I shot you,’ she said, and slipped into the bed. ‘But I did it to save your life.’

Mark pulled off his tie and began to undo the buttons on his shirt. They made love, then ordered food and drink – two omelettes and fries and a bottle of champagne – and, after they’d eaten, and drunk, they made love again. [CHAPTER ENDS] The problem here is that the suspense dissipates. Mark begins to undress but we don’t bother to wonder what will happen next – whether he and the woman will have sex, or try to but be interrupted, or do the deed and grab some food. We don’t need to – we’re told. Fear not! This is actually a tweaked version of an excerpt from Solo by William Boyd, Vintage, 2014 (pp. 259–60). Boyd is cannier. This is what it really looks like:

In the real version, we do ask those questions. The artistry lies in the fact that we have to turn the page to find the answers and relieve our suspense. They’re given in the next chapter. A sex scene follows. It’s an interlude – a chance to breathe, for them and us – before Bond leaves and sets up a diversion that will confuse the CIA’s surveillance of him. 2. Wrap up the chapter with foreshadowing Chapter endings that tell of incoming storms are powerful. When they’re short and taut, even better! Take a look at this super example from p. 210 of Clare Mackintosh’s Let Me Lie (Sphere, 2019):

That final line is like a punch in the gut. It begs us to ask: When will he come? What will he do? And how will she protect herself? It’s six words of masterful suspense. 3. Wrap up the chapter with emotional reflection In the The Man with No Face by Peter May (Riverrun, 1981), the protagonist, a journalist called Neil Bannerman, walks into a restaurant and alerts a minister that he has evidence about a government cover-up. That’s the juicy bit. Bannerman then exits, leaving the minister to mull over the revelation. That’s the mundane bit and May needs a way to close the chapter with a pop. Emotional reflection is the tool of choice. Here’s the excerpt from p. 233:

The journos and minister won’t be enjoying their meal but this isn’t an exercise in gastronomy. The end-of-chapter suspense comes in the form of questions: Will there be consequences for Bannerman? How will those play out? Will the minister get his just deserts? 4. Wrap up the chapter with a surprise interruption Another way of wrapping up a chapter when the big stuff has already played out is to introduce some sort of surprise interruption. Perhaps there’s a knock on the door from an unexpected visitor, or an odour that forces the viewpoint character to direct their attention elsewhere. Here’s another excerpt from Let Me Lie (p. 226). Murray, the viewpoint character, has just had a telephone call with Anna, during which he told her that her parents had indeed been murdered. She becomes emotional and commands him to drop the investigation, despite her bringing the case to him in the first place. What would ordinarily be a domestic mundanity serves to show his mood; his shock is so immersive that he’s forgotten everything around him until the alarm goes off. We leave the chapter imagining the shrill noise, the odour of burnt food, the smoke in the kitchen, and wondering what on earth has happened to make Anna change her mind. 5. Wrap up the chapter with a shocking last line There’s nothing better than a final line that the reader doesn’t see coming. Here’s a magnificent example from David Baldacci’s True Blue (Kindle edition, Macmillan, 2009). In Chapter 4, we meet Roy, a young lawyer. He finishes a game of basketball and slopes back to the office where, we learn, he earns a healthy pay cheque by plea-bargaining on behalf of mostly guilty defendants.

Baldacci sets up the whole chapter as just another day at the office. We should know better than to be lulled into this false sense of security, but Baldacci’s narrative is strong enough from the start to convince us this might go in another direction. Maybe Roy is crooked. Perhaps he’s about to be fired. Maybe he’s going to get a phone call telling him he has to go to court and represent someone he’d rather not. What we don’t expect is the wallop when a body falls out of the fridge. And now we have a ton of suspenseful questions. Who is she? How did she get in the fridge? Why was she killed? To find out, we’ll have to turn the page. 6. Wrap up the chapter with dialogue that demands answers One great line of dialogue can close a chapter beautifully. No action beats, no narrative, no response – just the spoken word. It works as an outro when the speech leaves us with questions, and therefore in suspense. Here's an example from New Tricks by David Rosenfelt (2009, Grand Central Publishing, pp. 215–16): The dialogue forces us to wonder: Why has Richard not carried out the redirect? Has some new evidence come to light? How will this affect the case? Rosenfelt doesn’t dampen the suspense by cluttering his prose with the detail of what came next – maybe people in the courtroom looked surprised or confused; perhaps there was an objection, and the judge banged their gavel and announced a recess. Instead, all that stuff is left unwritten – we just imagine it. It’s one line of dialogue and the chapter’s done. 7. Wrap up the chapter in the middle of one character’s speech Here’s Rosenfelt again in Dog Tags (Grand Central Publishing, 2010, pp. 28–9). Unlike in the example above where there’s a natural chapter break because of a shift from the courtroom to the chambers, this time he inserts the chapter break in the middle of one person’s speech. Less experienced authors might shy away from this, but it can work – if it’s an appropriate suspense point that leaves the reader reeling with questions.

That final line is a shock, for lawyer Andy Carpenter and us. Why would a dog need a lawyer? How can such an absurd conversation be happening? We learn the answers to these questions in the next chapter, and that’s exactly where they should be because ‘The government’ is the suspense point that grabs us by the scruff of the neck and demands we keep reading. Do you know when it’s closing time? Like artists who can’t put down a paintbrush, less confident writers sometimes lack the courage to end with one line that evokes questions rather than solutions. Yet that’s what the authors in all the examples above have done, and that’s why their outros are suspenseful and page-turning. If your chapters have a saggy bottom, maybe you haven’t identified closing time. I line edit for an author who writes knockout chapter endings … he just places them 10 lines further up the page than they should be to create a suspenseful finale! When you find yourself stuck, look up the page to find the point that will make the reader think How’s that going to play out? or Why did she do that? or That was a surprise! or Ha! You deserved that. … those few lines that will kick them up the backside and push them forward. If those lines are already there, think about whether they should be moved to the end of the chapter, or whether the prose after them should be shifted (or even deleted). If they’re not there, write them. Think about the very last sentence in your chapter too. How long is it? Your writing style and genre might dictate the style of your final lines but notice how lean the word count is in most of the examples above. The brevity acts like a command: Read me. Pay attention. Turn the page. Summing up Every chapter should end with a pop, regardless of genre. Those last few lines are what the reader remembers before they pause. An otherwise beautifully crafted chapter can be ruined if it flops at the finishing line. Find the suspense point – the lines that make readers ask questions – and use them to wrap up your chapter. And pay attention to the very last sentence. Sometimes less is more. Related resources

Louise Harnby is a line editor, copyeditor and proofreader who specializes in working with crime, mystery, suspense and thriller writers.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

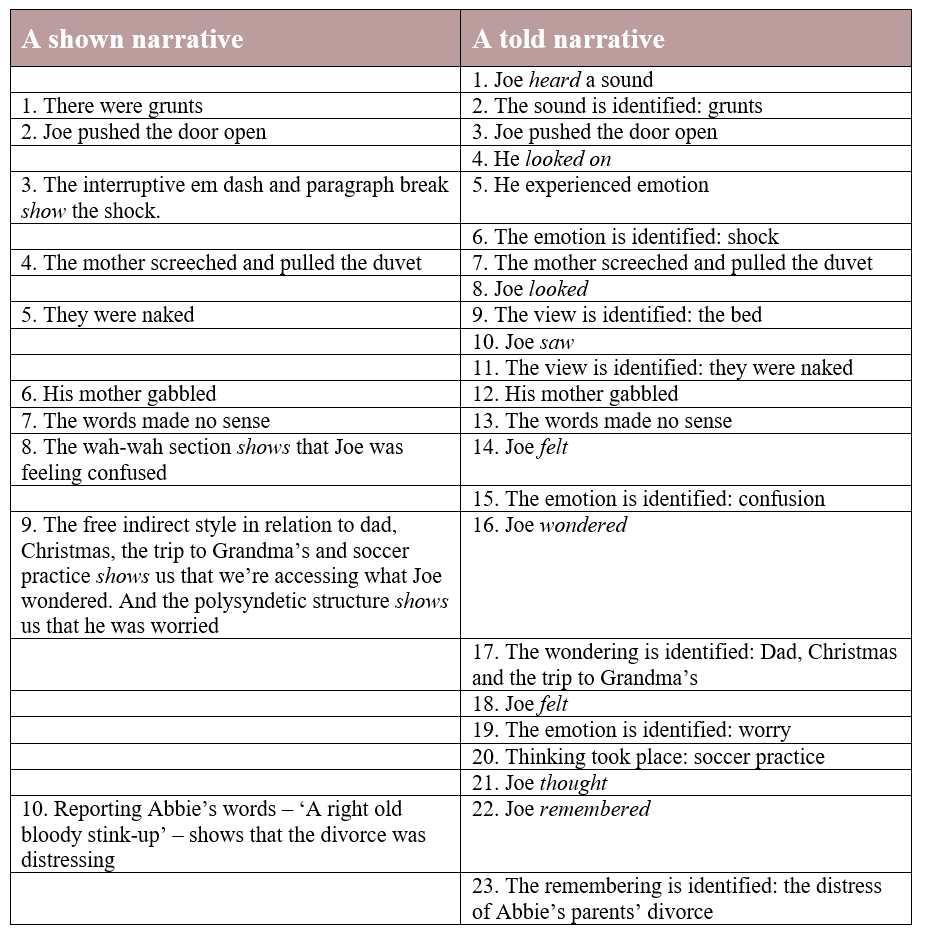

Are you storytelling-telling? Too much told narrative can force the reader to experience a story through extraneous layers that add clutter rather than clarity. Here’s how to identify one type of told prose and write with more immediacy.

|

|

‘[…] My father described the regular pom-pom-pom of the cannons and the increasingly high-pitched wails of the planes as they dived. He said he’d heard them every night since.

‘The last day of the battle he was standing on the bridge when they saw a plane emerging. […] Then he jumped overboard and was gone.’ The Bat (p. 251), Jo Nesbo, Vintage, 2013 |

Single versus double quote marks

There’s no rule, just convention.

There are lots of Englishes: US, UK, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand, South African, Indian, etc. Each has its own preferences and idiosyncrasies.

Focus on which English your audience will expect, and punctuate your writing accordingly. Whichever style you choose, the main thing is be consistent.

- In the UK, it’s more common to use single quote marks. And if there’s a quote within the quote, that’s a double. You might hear quotes within quotes called nested quotes.

- In US English it’s conventional to use double quote marks with nested singles.

|

Ray studied his drink and narrowed his eyes. ‘You can be cruel sometimes, you know. I don’t know where you got it from. “How sharper than a serpent’s tooth …” Your mother didn’t have a cruel bone in her body.’

Sleeping in the Ground (p. 261), Peter Robinson, Hodder & Stoughton, 2017 “I had no idea why he was bringing that up now. So when I asked him he said, ‘Remember when the going got tough, who was there for you. Remember your old man was right there holding your hand. Always think of me trying to do the right thing, honey. Always. No matter what.’” The Fix (p. 428), David Baldacci, Pan Books, 2017 |

If you choose double quote marks, use the correct symbol, not two singles.

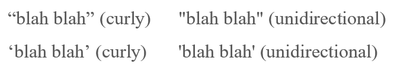

Straight versus curly quote marks

Curly quote marks are more conventionally known as smart quotes.

It’s conventional in mainstream publishing to use smart or curly quotation marks, not unidirectional ones.

- Go to FILE and select OPTIONS

- Select PROOFING, then click on the AUTOCORRECT OPTIONS button

- Choose the AUTOFORMAT AS YOU TYPE tab

- Make sure there’s a tick in the "STRAIGHT QUOTES" WITH “SMART QUOTES” box

- Click on OK

If you’ve pasted material into your book from elsewhere, or you didn’t check autocorrect options before you began typing, there might be some rogue unidirectional marks in your file. To change them quickly, do a global find/replace:

- Select CTRL+H on your keyboard to open FIND AND REPLACE

- Type a quotation mark into the FIND WHAT box

- Type the same quotation mark into the REPLACE WITH box

- Click on the REPLACE ALL button

The closing quote mark in relation to other punctuation

In fiction, punctuation related to dialogue is placed similarly whether you're writing in US or UK style: within the quote marks.

Here are some examples:

- "Don't move a muscle," Stephen said.

- "My God! Is that Jonathan? He looks fabulous."

- “Maybe you don't think we've met but I can assure—”

- Dave glanced at the signature tattoo on the Matt’s hand. ‘That looks familiar. Who inked you?’

- ‘Never.’ I sized up the door and the window. ‘I love you ...'

However, there's a difference when it comes to distancing or cited works. Note the different placement of the commas and full stops in the US and UK examples. In US English, the commas come before the closing quotation marks; in UK English, they come after.

- US English convention: Peter's "friends," the ones who hadn't bothered to find out if he was okay after his wife ditched him, seemed oddly keen to get in touch now that he'd won the lottery.

- UK English convention: Peter's 'friends', the ones who hadn't bothered to find out if he was okay after his wife ditched him, seemed oddly keen to get in touch now that he'd won the lottery.

- US English convention: "Favourite Jimi Hendrix songs? 'Foxy Lady,' 'Hey Joe,' and 'Purple Haze.'"

- UK English convention: 'Favourite Jimi Hendrix songs? "Foxy Lady", "Hey Joe", and 'Purple Haze".'

When not to use quote marks

There are 2 issues to consider here:

- Thoughts

- Emphasis

Thoughts

CMOS at section 13.43 says you can use quote marks to indicate thought, imagined dialogue and other internal discourse if you want to. However, I recommend you don't. For one thing, I can’t remember the last time I saw this approach used in commercial fiction coming out of a mainstream publisher’s stable.

But the best reason for not putting thoughts in quote marks is because it might confuse your reader. The beauty of quote marks – or speech marks – is that they indicate speech. Let them do their job!

Emphasis

It can be tempting to use quote marks in your writing to draw attention to a word or phrase, but it’s rarely necessary and could even have the opposite effect to what you intended. It works instead as a distancing tool, as discussed above.

If you’re tempted to use quote marks for emphasis, imagine saying the sentence out loud, and making air quotes with your fingers as you speak. Would your character/narrator say it like that? If the answer's no, leave out the quote marks. Italic will work better. Or recast your dialogue so that the reader can work out where to place the stress themselves.

Summing up

If in doubt about how to use quote marks for your book, consult a style manual. I recommend the Chicago Manual of Style, the Penguin Guide to Punctuation and New Hart’s Rules, all of which offer industry-standard guidance.

If you'd prefer to listen to the advice offered here, Denise Cowle (a non-fiction editor) and I chat about how to use quote marks in all types of writing on The Editing Podcast. You can listen right here or via Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast platform

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Think of your book as a construction project.

First you lay the foundations and build the walls – writing and redrafting to ensure the structure of your storytelling is sound. It’s where you and your editor (if you have one) focus on the big-picture stuff such as:

- Plot

- Pace

- Characterization

- Voice

- Tense choices

- Viewpoint decisions

At this macro stage, you might end up adding, deleting or shifting sections of your prose.

Some authors do their own structural editing because they’re good at it and have studied story craft via writing courses, groups or books. Others seek professional help, either because they’re at an earlier stage of their authorial journey or because they feel they’re too close to the book to see the problems.

One thing’s for sure – there’s no right or wrong way. Every writer has to make their own choices.

If a full, done-for-you developmental (or structural) edit isn’t the path you take, you might still decide to work with a specialist editor who analyses your book and provides a detailed report on its strengths and weaknesses at story level, and offers suggestions about how to improve your writing.

That’s where story-level critiques come into play. You might also hear them called manuscript evaluations and manuscript assessments.

Once the foundations and walls are in place, it’s plastering time – smoothing at sentence level to ensure that a reader’s journey through the pages is satisfying. In a sense, it’s still structural work but at a micro level. This is where you (and your editor if you have one) focus on nuances such as:

- Viewpoint

- Spelling, grammar, syntax and punctuation

- Dialogue

- Narrative readability

- Character description

- Thoughts

- Action beats

- Shown and told prose

- Tenses

- Formatting

Again, some authors do their own line editing because they’re good at it and have studied line craft via writing courses, groups or books. Others seek help.

If a full, done-for-you line- and copyedit isn’t an option, a line critique could be just the ticket.

A line critique, like its story-level sister, is an assessment or evaluation of your story but at sentence level. Your report will include examples from your novel that show what’s holding you back.

You’ll also be offered suggestions on how you can fix any problems identified. Then you can implement what you learn throughout the rest of your book.

Some authors are nervous about critiques. Pro editors get it – it can be tough to put your book in the hands of another and ask them to tell you what’s working and what’s not, especially when you’ve put in so much hard work.

The thing to remember is that a critique (whether at sentence or story level) is not about criticism. It’s about identifying strengths and weaknesses, and offering solutions so that you can move forward to the next stage of your publishing journey with confidence.

And critiques are a long-term investment. They enable you to improve your self-editing skills. That’ll save you time and money further down the line because anyone else you commission will have less to do.

The line critique: the process and the report

What follows is an overview of the way I handle line critiques. Every editor has their own process, but the basic principles will be similar.

1. The service: Mini line critique

Authors email a Word file comprising, say, 5K words of their novel. It’s in a writer’s best interest to include a section that includes both narrative and dialogue. That way we can assess whether both are working effectively.

Furthermore, if there are multiple viewpoint characters in the novel, and different viewpoint styles and tenses have been used, a sample that represents these choices will enable us to provide a report that evaluates the success of those decisions.

2. First readthrough

The first stage of the process is a complete readthrough of the 5K words. It’s not about micro-level reporting, not yet. Rather, we’re getting a sense of the author’s writing style, the characters’ voices, and the flow of the narrative.

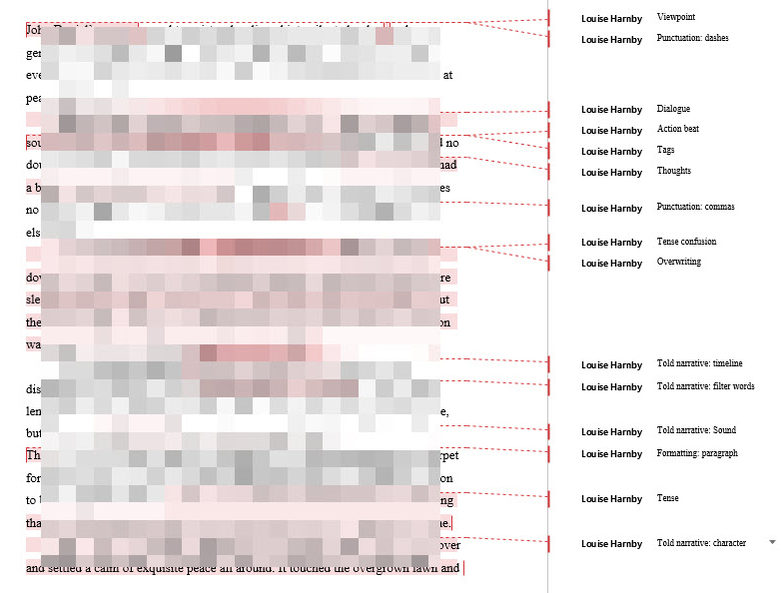

3. Second pass: Identification tagging

We go back to the beginning and start the analytical process, identifying the strengths and weaknesses of the author’s line craft.

We work through the sample, tagging sections of the text with Word’s commenting tool. The author won’t see these tags – they’re just a tool that allow us to locate the sections we’ll pull from the text and into the report for demonstration.

The text in the image below has been blurred in order to respect confidentiality, but you can see the tagging process in the margins of just one page of one of my reports.

Now that we’ve tagged the sample, we can create a report. Line critiques are usually between 20 and 30 pages long, depending on the length of the text samples the editor is pulling in and offering recasts for.

Each report is divided into sections that address the strengths and weaknesses of the following:

NARRATIVE

- Clarity of narrative viewpoint

- Tense choice

- Showing and telling

- Character description

- Filter words

- Action beats

- Sentence length, flow and rhythm

- Adverbs and adverbial phrases

- Tentative language in relation to a told narrative

DIALOGUE AND THOUGHTS

- Voice, mood and intention

- Dialogue layout

- Dialogue punctuation

- Effectiveness of dialogue tags

- How thoughts are styled

TECHNICAL ELEMENTS

- Spelling

- Punctuation

- Grammar

- Syntax

FORMATTING

- Pre-proof layout recommendations

- Using Word’s styles tool

The tags in the sample allow editors to search for and locate the text we want to use as examples of good practice and to highlight areas with improvement potential.

Here’s an example of one of those sections (I’ve disguised the identifying traits of the original in order to respect the author’s confidentiality):

What worked

You held narrative viewpoint well and I commend your decision to separate the two viewpoint characters with chapters. This ensured the narrative voices remained distinct.

Using a present-tense second-person POV for your transgressor and a past-tense first-person POV for your protagonist worked extremely well. Have you read Complicity by Iain Banks? He does the same thing! It’s effective because it makes us wonder whether that first-person narrative is reliable, though you don’t give the game away until the denouement, which I loved.

The second-person POV also lent a rather creepy voyeurism to the transgressor chapters, and though these were demanding to read, you did give your readers plenty of breathing space with the contrasting protagonist chapters. Nicely done!

What could be improved

Your protagonist narrative was laboured at times because of the abundance of ‘I’. Overusing this pronoun can lead to an overly told narrative in which the reader is forced to experience everything via the character’s experience of it. This can be distancing. I’m not suggesting you remove every instance of ‘I’ plus the verb – not at all. Instead, consider toning it down and removing some of the filter words so that the reader can experience some of the doing with the character rather than through the character. Here are two examples and suggested fixes:

- ORIGINAL (p. 14): I looked up and saw a shooting star zipping through the night sky.

- SUGGESTED EDIT: I looked up. A shooting star zipped through the night sky.

Notice how I’ve suggested removing ‘I saw’, which feels redundant given that we already know that Marcus is looking up, and only tells us of more seeing being done. Instead, you can focus the reader’s attention on the immediacy of what’s seen once the looking up’s happened: the movement of the shooting star. That allows you to show readers what Marcus sees rather than telling them.

- ORIGINAL (p. 24): I scuttled towards the garage and hid behind a large oak tree. I heard the sound of Phil’s boots on the gravel underfoot and smelled the sharp aroma of his awful aftershave. I realized he was close, about two feet away from me.

- SUGGESTED EDIT: I scuttled towards the garage and hid behind a large oak. Gravel crunched. Rank aftershave tickled my nose. Phil was close, a couple of feet at most.

Notice how in the original there’s a lot of telling of what ‘I’ did. I like your use of a strong verb to introduce tension – ‘scuttled’ – but that tension dissipates with the more distant told narrative that follows. There’s telling of sound, smell, and realization. I’ve suggested you tighten up the paragraph by retaining the original anchor in which Marcus hides; perhaps follow that with a shown narrative that, again, allows the reader to experience the sounds and smells at the same time as Marcus rather than through his ears, nose and brain’s doing hearing, smelling and realizing.

Recommendation

Bear in mind that a first-person narrative, by definition, puts the reader in the character’s head. If you keep that in mind, you’ll save yourself a lot of work because you’ll need fewer words on the page.

Have a read through all the protagonist chapters and consider where you can tighten up the prose in order to limit some of the telling of doing being done. You can still anchor the first-person viewpoint with ‘I’ in places, of course, but you might recast some of writing that follows with shown action.

5. Wrapping up and emailing the report

When the report is complete, we save it as a PDF and email it to the author. PDF is the tool of choice for many editors because it can’t be edited. If the client wishes to refer back to it during future writing projects, they can do so safe in the knowledge that nothing’s been accidentally removed.

Summing up

If you want to hone your line craft and polish your book at sentence level, but a full line- and copyedit is beyond your budget, consider a more affordable alternative: the line critique.

Think of a critique as another form of authorial development, of book-craft study. And what you learn from your critique won’t be something you can apply just to the current book. It’s a tool you can use with every story you write thereafter.

And here’s a free booklet that outlines the various levels of editing. Just click on the cover to get your copy (and, no, you don’t have to give me your email address!).

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

This free booklet shows you how to stay on track. To get it, head over to the Grammar and Spelling section of my Resource Centre.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

- Flatness: Tension and dynamism are reduced

- Woolliness: The narrative voice can’t make its mind up

- Distance: The reader is pulled away from the story

Authors sometimes introduce tentative language into a novel because:

- They’re afraid of dropping viewpoint

- Their narrative voice lacks confidence

- They think it’s appropriate

Tentative language: words to watch out for

I’m not suggesting you remove every tentative word; some might be deliberate and necessary. More likely, you’ll be checking that your prose isn’t rife with them.

Still, these little blighters can slip in accidentally and it’s worth taking the time to root them out and decide whether to give them space on your page or remove them.

Here are some of the words (or word groups) to watch out for:

- as if to

- almost as if

- appeared to

- considered

- could

- hoped

- looked as if/looked like

- maybe

- might

- perhaps

- presumably

- probably

- seemed

- thought

- wondered

When there’s a problem, it can sometimes be fixed with a simple deletion, or a stronger verb.

When viewpoint, tension and reader immersion are at stake, more intervention might be required.

How to fix it without dropping viewpoint

I see the likes of seemed, appeared, and looked as if creeping frequently into line editing projects for less experienced authors because they want to hold viewpoint.

Hats off to them – I’ll take a seemed over a head-hop any day of the week! Still, there might be a better fix.

Here’s a framework you can use to recast in a way that removes the uncertainty but keeps the narrative alive.

|

Fixing framework that holds viewpoint

|

|

Luke peeked around the headstone. The hooded man seemed frustrated.

The sentence is flat though. Yes, we readers are still in Luke’s head but it’s not a particularly interesting space. There’s no tension in our observations from his hiding place.

Here’s how the fixing framework helped me recast in a way that shows readers the hooded man’s assumed frustration, as seen by Luke:

Luke peeked around the headstone. The hooded man glanced at his watch and swore under his breath. His foot lashed out, knocking over a grave vase. The stagnant water stunk and Luke wrinkled his nose.

Thom turned and tripped over the blind guy’s white stick – Mikey, someone had called him. He looked at Mikey, who seemed almost to be picking out Thom’s facial features in his mind.

But there’s a problem. If Mikey were the viewpoint character, his imagining Thom’s face would make for an interesting narrative. However, it’s Thom’s head we’re in. In this case, the assumption seems off, too big to believe.

When I listen to someone speaking, I tend to use my eyes to focus on their mouths; my friend with restricted vision tends to move his head so that his ears are more in play. Sighted people in his company need to be aware that his eyes don’t focus directly on a speaker even though he’s fully engaged.

If we place this experience within the fixing framework, we can imagine Mikey’s physicality and the effect on Thom, the viewpoint character.

Thom turned and tripped over the blind guy’s white stick – Mikey, someone had called him. Mikey tilted his head, gaze off-centre, ear trained on Thom’s blustered apology.

How to fix an insecure narrative voice

In the examples below, the tentative words have crept in because the authors are still developing the confidence to make every word count.

Useful tools of the trade include deletion, stronger verbs, smoother recasts, and free indirect style.

The fixes below are suggestions only, offered so you have an idea of what to look out for and how you might tackle the solution. The approach you use will depend on your writing style and the mood of the scene.

When tentative language creates a flat sentence

In these examples, the tentative mood is justified but the sentences are rather flat. We need to inject tension.

|

Original

|

Tamsin Johns came to mind. He wondered what her story was.

|

|

Free indirect style

|

Tamsin Johns came to mind. What the hell was her story?

|

|

Original

|

Confused, Ava wondered if he’d thought she was going to rob him.

|

|

Recast

|

Ava shook her head. It was odd, like the guy had thought she was going to rob him.

|

|

Original

|

Arty thought the new door seemed not to fit the others in the old house.

|

|

Recast

|

Arty touched the cherrywood door. It was different to the others, the grain fine and straight, the lacquer smooth under his fingertips.

|

In these examples, the tentative words relate to viewpoint characters’ experiences. The uncertainty introduces distance because it pulls the reader out of their experience. It makes us say, ‘Why the lack of commitment? Doesn’t the viewpoint character know?’

Once more, I’ve used real examples and adapted them to disguise the originals.

|

Original

|

Her body appeared to hum with fear.

|

|

Deletion

|

Her body hummed with fear.

|

|

Original

|

Eleanor gasped as the craft shot into the air and was gone in what seemed like an instant.

|

|

Deletion

|

Eleanor gasped as the craft shot into the air and was gone in an instant.

|

|

Stronger verb

|

Eleanor gasped as the craft shot into the air and vanished.

|

|

Original

|

Debs scrolled through her contacts, found his name and hit DELETE. Hilary probably thought she could do better, and Debs agreed.

|

|

Deletion

|

Debs scrolled through her contacts, found his name and hit DELETE. Hilary had said she could do better, and Debs agreed.

|

In these examples, the tentative words work. They show the reader that the viewpoint character is guessing.

She glowered as if to say, You really think there’s enough meat on that plate?

Mark glanced at the blue car. There were two people inside, neither familiar. Might be undercover cops, but he legged it anyway … just in case.

Mark glanced at the blue car. There were two people inside, neither familiar. Might be undercover cops, but he legged it anyway … just in case.

A haze hung in the air – maybe brick dust from the fallen building or ash from the fire. It stung his eyes and irritated his throat.

The news knocked the breath out of her. Jamie had seemed happy the last time they’d met. Ecstatic even, what with the new job, the kayaking holiday, that girl he’d met the week before.

She combed the beach for Ben’s blue sun hat, pushing the unthinkable to the back of her mind. Thought it through. Probably with Mark at the rockpool. The café maybe. Or the groyne or the dunes. Her head spun left, right, left again.

Summing up

As soon as a writer or editor begins line editing fiction, subjectivity comes into play. It’s rare that there’s a right or a wrong way.

With that in mind, don’t ban tentative language in your prose; just watch out for it. It may well have the right to be there, though it shouldn’t trump tension or add clunk.

If removing it messes with viewpoint, use the fixing framework to craft an alternative shown narrative.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Find out more about ...

- Word count

- File format

- Genre or subject

- Previous rounds of editing

- Type of editing required

- Audience and publishing path

- Time frame

- Other published works (online or in print)

- Sourcing editorial assistance

Mentioned in the show

- The Editing Podcast, Point of view: On editing erotica. With editor Maya Berger

- The Editing Podcast, S1E1: The different levels of editing

- The Editing Podcast, S1E6: What is a sample edit?

- The Editing Podcast, S2E9: Writing and editing for the web. With Erin Brenner

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Find out more about

- What a copyediting service includes

- When fact checking takes place in the editorial process

- Fiction: place names, historical accuracy, idiom, dates, etymology

- Non-fiction: people names, obscure terms, place names, dates, protecting author reputation

- Differences between spot checking and fact checking

- Fact checking for consistency across series

- Print versus digital: preventing reputational damage in the long term

- Tools for fact checking

- Who’s responsible for fact checking?

- Effective and sensitive querying of facts in non-fiction

- Artistic licence with facts in fiction

Related links and resources

- Laura Poole, Archer Editorial

- Tool: Internet Movie Database (IMDb)

- Tool: The Historical Thesaurus of English

- Tool: Google Ngram Viewer

- Tool: CIA – The World Factbook

- Tool: The New Food Lover's Companion (Barron's Cooking Guide)

- Tool: Research tools for crime and thriller writers

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Find out more about:

- Why authors shouldn’t fear approaching an editor

- Why erotica deserves the same editorial rigour as any other genre

- The rise of romance and erotica in mainstream publishing

- How to find an editor who specializes in erotic fiction

- Subgenres and the benefits of specialist editing: LGBTQ, kink and taboo (BDSM and powerplay dymanics)

- Sensitivity reading: representing voice and identity

Related links and resources

- Maya Berger (website): What I Mean To Say

- Maya Berger (CIEP listing)

- Directory of Editorial Services: Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP)

- Finding an editor (blog by Louise)

- Finding an editor (podcast): The Editing Podcast, S1E10, How to Find an Editor

- Copyediting and proofreading pornography and erotica (blog by Louise)

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Here’s an overview of the present tense, with basic examples:

- Simple present: I write a novel; he writes a novel

- Present progressive (also called present continuous): I am writing a novel; he is writing a novel

- Present perfect: I have written a novel; he has written a novel

- Present perfect progressive: I have been writing a novel; he has been writing a novel

The present is immediate, and that right-nowness forces the reader to stick close to the viewpoint character. We’re in the moment with them. That’s why it appeals to some fiction authors, and why others find it restrictive.

With second-person viewpoints, the present tense is intensely voyeuristic, invasive even. Here’s an excerpt from Iain Banks’s Complicity (p. 60). This is a transgressor narrative with a difference – the narrator is anonymous, at least until later in the novel:

|

You stand up, reach forward and take the neatly folded handkerchief out of the breast pocket of his jacket, flick it open and wipe the blade of the Marttiini on it until the knife is clean. The knife comes from Finland; that’s why the name has such a strange spelling. It hasn’t occurred to you before, but its nationality seems appropriate now and even funny in a grim sort of way; it’s Finnish and you’ve used it to finish Mr Persimmon.

|

And in this example from a later chapter (p. 90), we’re back with the protagonist. Here, the main narrative tense is present. The viewpoint is first-person:

RECOMMENDATION

The present tense is great if you want to shorten the distance between the reader and the viewpoint character.

Present tense works particularly well for short fiction because space is limited. I use it often in my own shorts and flashes because it enables me to pack an immersive punch quickly.

However, it’s tricky to manage if there are multiple viewpoint-character chapters or sections, all operating in the present tense. You’ll need to keep a close eye on the timelines so that the reader’s clear on what ‘now’ really means. If your plot twist hinges on deliberately duping them via your use of tense rather than story craft, you’ll break their trust.

The present tense can also be tiring for readers because it’s emotionally immersive. If you’re writing a novel, you might consider using it only for certain viewpoint characters – your transgressor or victim, for example.

In Let Me Lie, Clare Mackintosh mixes it up: the Anna-viewpoint chapters are set in first-person present; the Murray-viewpoint chapters are third-person past.

The past tense

Now let’s turn to the past tense, starting with some basic examples:

- Simple past: I wrote a novel; he wrote a novel

- Past progressive: I was writing a novel; he was writing a novel

- Past perfect: I had written a novel; he had written a novel

- Past perfect progressive: I had been writing a novel; he had been writing a novel

- Habitual past: I would write a chapter every week; he would write a chapter every week; I used to write a chapter every week; he used to write a chapter every week

The past tense is the choice of most contemporary commercial fiction writers. What’s interesting is that readers are so used to this style that they can still immerse themselves in a past-tense narrative as though the story is unfolding now.

Here’s an excerpt from T. M. Logan’s 29 Seconds (p. 73). We’re given a past-tense narrative with a third-person limited viewpoint (Sarah’s):

WHEN PAST TENSE FLOPS – UNDERSTANDING PAST PERFECT

Less experienced writers can end up in a pickle when referencing events that happened earlier than their novel’s now.

The crucial thing to remember is that when we set a novel in the past tense, anything that happens in the story’s past will likely need the past perfect, at least when the action is introduced.

|

What you want the reader to experience

|

What tense you should write in

|

|

Now – the present of your novel

|

Simple past or past progressive

(she stood; she was standing) |

|

Something that happened before now (i.e. in the novel’s past)

|

Past perfect

(she had stood; she had been standing) |

|

She stood there for a moment, taking in the white Christmas lights Samantha had wound through the slats of her bed’s headboard, and the fuzzy green-and-blue rug the two of them had found rolled up by the curb of a posh apartment building on Fifth Avenue. “Is someone actually throwing this out?” Samantha had asked.

|

When we’re told that ‘She stood’, that’s the novel’s now. But when the narrator recalls events that happened further back in time (bold) – Samantha’s decorating her bed, and the two women’s procuring a rug – these need to be anchored in the past-perfect tense: had, had been.

When authors fail to anchor past events in a novel whose now is already set in the past tense, the reader will be confused.

RENDERING BYGONE ROUTINE – UNDERSTANDING HABITUAL PAST

Now and then, you might want to reference events from your novel’s past that happened routinely or habitually. This is where the habitual past tense comes into play, and the tools are would and used to.

This excerpt from The Templar's Garden by Catherine Clover illustrates the usage. The narrative is set in third-person past but the viewpoint character is recalling regular journeys taken earlier in her life:

And in Time To Win (p. 62), Harry Brett uses the simple past and past progressive for the most part, but then Frank, the viewpoint character, recalls something he’d done habitually in former times:

|

Tatty was talking to Simon. Frank couldn’t hear what they were saying. He looked down the road, towards the harbour and the dead end, the industrial buildings laid low by the unexpected weight of late summer sun, and somewhere over to his left the top of Nelson’s Monument, clear of cloud for once. He used to enjoy driving down South Denes Road and curving back round onto South Beach Parade, accelerating past the old Pleasure Beach and into a different era.

|

Like the past perfect, the habitual past acts as an anchor, so that readers don’t mix up the reminiscence of a routine event with the novel’s now.

To see that confusion in action, replace ‘used to enjoy’ with the simple past: ‘enjoyed’. It reads as if Frank is enjoying driving down South Denes Road right now.

If you don’t want to use the habitual past, then an alternative anchor is necessary. Here I’ve added an anchoring clause and changed the tense to past perfect (he’d, or he had):

- Back in the day, he’d enjoyed driving down [...]

RECOMMENDATION

The past tense is flexible; it’s easier to shift narrative distance (the distance between the reader and the narrator) than is the case with the present tense, though this does increase the risk of flatter writing. Dramatic scenes – fights, escapes, arguments – could end up laboured if the writing isn’t lean and rich.

Still, it’s traditional and readers are used to it. No one will get tired of reading in the past as long as the line craft is strong.

Do take care, however, with rendering events that have taken place in your novel’s past. Use the past perfect or the habitual past when necessary to ensure your readers know what happened when.

Summing up

Write in the tense you feel most comfortable with, and that you think readers of your genre will be most comfortable reading. The past and the present both have their challenges and their advantages. The most important thing is that readers know where and when they are in the story.

Cited sources

- 29 Seconds, T. M. Logan, Zaffre, 2018

- Complicity, Iain Banks, Abacus, 1994

- The Templar’s Garden, Catherine Clover, The Holywell Press, 2017

- The Wife Between Us, Greer Hendricks and Sarah Pekkanen, Pan, 2018

- Time to Win, Harry Brett, Corsair, 2017

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Dashes are sometimes referred to as ‘rules’, especially in the UK. Oxford’s New Hart’s Rules (NHR) refers to the ‘en rule’ and the ‘em rule’ whereas The Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS) discusses ‘en dashes’ and ‘em dashes’.

Both terms are acceptable but I’ll use ‘dash’ in this article.

A word on exceptions

Take a look at the likes of CMOS and you’ll see plenty of exceptions to the rules, which is why I don’t much like rules when it comes to fiction editing! What I’ve given you here is what I think you’ll need to know most of the time for most of your novel writing.

What do the dashes look like?

There are four dashes you’re most likely to use in fiction:

- Hyphen: -

- En dash: –

- Em dash: —

- 2em dash: ⸺

Dashes that set off text and replace alternative punctuation

The EN DASH and the EM DASH can be used to set off an augmenting or explanatory word or phrase in a sentence that could stand alone without the insertion.

Brackets, commas and colons can act as alternative forms of punctuation. Here are some examples that demonstrate how it could be done:

That old dog, the black one, is as sweet as they come.

That old dog – the black one – is as sweet as they come.

That old dog—the black one—is as sweet as they come.

She knew the name of that old dog – everyone did.

She knew the name of that old dog—everyone did.

That sweet old dog had a name – Patch.

That sweet old dog had a name: Patch.

In the UK, it’s conventional to use a SPACED EN DASH. This is not the law, not a rule, not the only way or the right way. It’s just the style that many UK publishers choose, though not all.

Here’s an example from my version of Stephen King’s The Outsider (p. 171):

In the US, it’s conventional to use a CLOSED-UP EM DASH. Again, this is not the law, not a rule, not the only way or the right way. It’s just the style that many US publishers choose, though not all.

Here’s what King’s sentence looks like when amended according to US convention:

Some style guides even ask for SPACED EM DASHES, though I see this usage less frequently:

I recommend you stick to spaced en dashes or closed-up em dashes in fiction because that’s what your readers will be most familiar with. As for which style you should choose, think about:

- where your target audience is based

- what they’re used to seeing

If you’re publishing internationally, pick one style and be consistent.

Dashes in number spans

In fiction, number spans are often written out, though again this is convention rather than a rule that must be adhered to. Number ranges might make their way into emails, texts, letters and reports in your story, and they’re perfect for date ranges.

A CLOSED-UP EN DASH between number spans is standard in publishing, whether you’re writing in British English or US English:

Morning registration: 9:30–11:30 (colons more often used in time styles in US English)

See pp. 86–95

The 1914–18 war was the war to end all wars

07/03/1967–26/06/2019 (day/month/year; standard in UK English)

03/07/1967–06/26/2019 (month/day/year; standard in US English)

Note that the en dash means up to and including (or through in US English).

CMOS and NHR both recommend using EITHER the closed-up en dash in a number range OR a from/to or between/and construction, but not a mixture of the two:

Read pp. 86–95 (standard)

Read from p. 86–95 (non-standard)

The war lasted from 1914 to 1918 (standard)

The war lasted from 1914–18 (non-standard)

I’ll be there between 9:30 and 11:30 (standard)

I’ll be there between 9:30–11:30 (non-standard)

Dashes as alternative speech marks

The CLOSED-UP EM DASH can act as an alternative to speech marks (or quotation marks) in dialogue in both UK English and US English.

Sylvain Neuvel uses this technique in Sleeping Giants and it works because the scenes in which it occurs take place in a secret location with an anonymous (even to the reader) agent running the interrogation. Each speaker’s turn is indicated with an em dash. The agent’s speech is rendered in bold.

—There is no need to get angry.

—I’m not angry.

—If you say so. You have a problem with authority.

—You don’t need a test to work that one out.

It can be an effective tool for fiction that’s dialogue driven – almost like a screenplay – but it gets messy when there are more than two speakers in a conversation, and becomes unworkable if you want to ground your dialogue in the environment with narrative (action beats, for example). And, of course, the dialogue needs to be standout because that’s all there is.

Dashes that indicate end-of-line interruptions

To indicate that a speaking character has been interrupted, use a CLOSED-UP EM DASH, whether you’re publishing in US or UK English.

Here’s an example from Mick Herron’s Dead Lions (p. 115)::

‘You got the guys—’

‘Yeah yeah. Catherine got the guys at the Troc to pick them up.’

And another from Linwood Barclay’s Parting Shot (p. 380):

“I know exactly who you are,” she said, and reached out and took his hand in hers.

Dashes for dialogue interrupted by narrative description

Dashes offer clarity when dialogue is broken by narrative description and the speaker hasn’t finished talking.

Here’s how it could be rendered in US English using CLOSED-UP EM DASHES:

And if you’re following UK English convention, use SPACED EN DASHES:

Notice how I’ve also used double quotation marks in the US version and singles for the UK one. Again, this isn’t about being right or obeying a rule; it’s a convention, and one that’s not always adhered to. Consistency is king.

Dashes that indicate faltering speech

If your character is out of breath, taken aback, caught off guard, frightened, or nervous, you might want to indicate faltering speech with punctuation.

There are no absolute rules about how you do this; it depends on the effect you want to achieve.

If you want to denote a staccato rhythm, HYPHENS are a good choice. This works for sharper faltering where the character stammers or stutters.

If the faltering related not to letters but to phrases, you could use a CLOSED-UP EM DASH (US style) or a SPACED EN DASH (UK style).

Ellipses are another option. They're not dashes but they're handy for faltered speech that has a pause in it. You can use these with your dash of choice.

"No. I-I-I mean, not really. It was an accident. I just s-s-saw him standing there and I flipped," Marion said.

Closed-up em dash for faltering phrasing (US style):

"I can't—I mean I shouldn't—well, it's difficult to know what to do."

Spaced en dash for faltering phrasing (UK style):

'I can't – I mean I shouldn't – well, it's difficult to know what to do.'

Ellipses for pauses (in conjunction with dashes):

'I can't – I mean I shouldn't – oh God ... you know what? It's d-d-difficult to know what to do.'

"No. I ... I mean, not really. It was an accident. I just s-s-saw him standing there and I flipped," Marion said.

Dashes as separators

HYPHENS are the tool of choice here. They’re short and sharp, and are perfect in fiction when you want to spell out words or numbers:

“That doesn’t make sense. The extension he gave me is 1-9-1-8. Are you sure it’s a five-digit number?”

Number separation comes in handy when you want to ensure your reader reads the numbers as distinct digits rather than inclusively. Compare 1918 (nineteen eighteen) with 1-9-1-8 (one, nine, one, eight).

Dashes that indicate connection, relation or an alternative

We use EN DASHES in place of to and and/or to show a connection between two words that can stand alone and that together are modifying a noun:

“Those two have had an on–off relationship for over a decade. I wish they’d make their minds up!”

‘I’m going to get the Liverpool–Belfast ferry. There’s one at ten thirty.’

Danny would take the money and Sheryl would get her promotion. It was a win–win.

I couldn’t see us winning the England–Brazil match but I put a tenner on us anyway. Just for fun.

Amir was an Asian–British scholar and something of a polyglot. ‘Languages float on the wind in my grandparents’ village,’ he once told me.

Dashes with adjectival compounds

Either EN DASHES or HYPHENS are used here, regardless of where you live.

When one adjective modifies another adjective, these words create a compound. If this compound is placed before a noun, it usually takes a HYPHEN for the purpose of clarity. When the compound comes after the noun and a linking verb, the hyphen can be omitted:

but

His shirt was navy blue.

“That well-read woman you were talking about? She’s called Sally.”

but

“Sally sure is well read, no doubt about it.”

Care should be taken, even in fiction, with regard to weighting. Let’s revisit the example of our polyglot Amir. Consider the differences between the following:

Amir was an Asian-British scholar and something of a polyglot. ‘Languages float on the wind in my grandparents’ village,’ he once told me.

Amir was an Asian British scholar and something of a polyglot. ‘Languages float on the wind in my grandparents’ village,’ he once told me.

Amir was a British Asian scholar and something of a polyglot. ‘Languages float on the wind in my grandparents’ village,’ he once told me.

In the first example, with an EN DASH, Amir’s Asianness and Britishness have equal weighting. In the second, with the HYPHEN, ‘Asian’ is modifying ‘British’ and carries less weight. In the third and fourth, where the dashes are omitted, the weighting is ambiguous.

The dash of choice (or its omission) can tell us something about Amir’s identity – how he, or the narrator, or the author perceives this – so it needs to be used purposefully.

Dashes indicating omission

You might want to omit words, fully or partially, because they’re profane, or to indicate that some of the letters are illegible, or to disguise a name.

There are several options for managing omission: em dashes, 2em dashes, en dashes and asterisks. Spacing comes into play. There are different conventions for US and UK style.

NHR recommends the following for UK style:

‘The scandal featured a certain Mrs H – – – – –. Can you believe it?’

‘I told you to p – – – off!’ he said, spittle flying.

‘I told you to p*** off!’ he said, spittle flying.

To indicate partial omission of a word with a single mark, choose the CLOSED-UP EM DASH:

‘The scandal featured a certain Mrs H—. Can you believe it?’

‘I told you to p— off!’ he said, spittle flying.

To indicate complete omission of a word with a single mark, choose the SPACED EM DASH:

‘The scandal featured a certain Mrs —. Can you believe it?’

‘I told you to — off!’ he said, spittle flying.

CMOS recommends the following for US style:

“The scandal featured a certain Mrs H⸺. Can you believe it?”

“I told you to p⸺ off!” he said, spittle flying.

To indicate complete omission of a word, choose the SPACED 2EM DASH:

“The scandal featured a certain Mrs ⸺. Can you believe it?”

“I told you to ⸺ off!” he said, spittle flying.

Summing up

Using dashes purposefully, and according to publishing convention, will bring clarity to your fiction writing. Think about your audience and what they’re used to seeing on the page, then choose your style and apply it consistently.

Consider, too, whether your choice of dash will amplify or reduce the significance (or weight) of your words when you’re using dashes as connectors or modifiers.

And if you’re still bamboozled, ask a pro editor. We know our dashes!

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

- Get in touch: Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader

- Connect: Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, Facebook and LinkedIn

- Learn: Books and courses

- Discover: Resources for authors and editors

Listen to find out more about:

- What quote marks are and how they're used

- Whether to use straight or curly quote marks

- Choosing single or double quote marks

- Where the closing quote mark goes in relation to other punctuation

- When not to use quote marks

Other resources

- Chicago Manual of Style

- Penguin Guide to Punctuation

- New Hart’s Rules

- How to punctuate dialogue in a novel (free webinar)

Music credit

‘Vivacity’ Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License.

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

Summary of Episode 27

- Why working with web content is different from writing for the page

- In which programs should we create content for the web?

- Pre-upload checks on the writing

- Pre-upload checks on metadata links, and alt-text

- Quality control: self-editing versus third-party professional help

- How many editing passes?

- Fact-checking and authenticity

- The order of play for editing web content

- Style sheets and web content

- Language choice and style for web content

Editing bites

- Erin Brenner’s Web Style Checklist

- They Ask, You Answer by Marcus Sheridan

Other resources

- Erin Brenner, Right Touch Editing

- ‘Customer service: A cautionary tale of red flags and safety nets’ by Vanessa Plaister on the CIEP blog

- The AP Stylebook (Associated Press)

Music credit

She is an Advanced Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), a member of ACES, a Partner Member of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), and co-hosts The Editing Podcast.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Fiction Editor & Proofreader, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, connect via Facebook and LinkedIn, and check out her books and courses.

BLOG ALERTS

TESTIMONIALS

Dare Rogers

'Louise uses her expertise to hone a story until it's razor sharp, while still allowing the author’s voice to remain dominant.'

Jeff Carson

'I wholeheartedly recommend her services ... Just don’t hire her when I need her.'

J B Turner

'Sincere thanks for a beautiful and elegant piece of work. First class.'

Ayshe Gemedzhy

'What makes her stand out and shine is her ability to immerse herself in your story.'

Salt Publishing

'A million thanks – your mark-up is perfect, as always.'

CATEGORIES

All

Around The World

Audio Books

Author Chat

Author Interviews

Author Platform

Author Resources

Blogging

Book Marketing

Books

Branding

Business Tips

Choosing An Editor

Client Talk